Perceived Importance and Quality Attributes of Automated Parcel Locker Services in Urban Areas

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Providing access to the house or its elements to the courier delivering the package, who places the package in an electronic terminal secured with a confirmation code;

- Leaving the package at the place of residence without the need to access the house, i.e., in the so-called home pickup box;

- Delivery of the package to a local agency, which, in turn, delivers the package to the customer’s home;

- The use of pick-up points, i.e., places where the customer can pick up the parcel on his own (they can be divided into self-service and those where the release of the parcel requires service by staff).

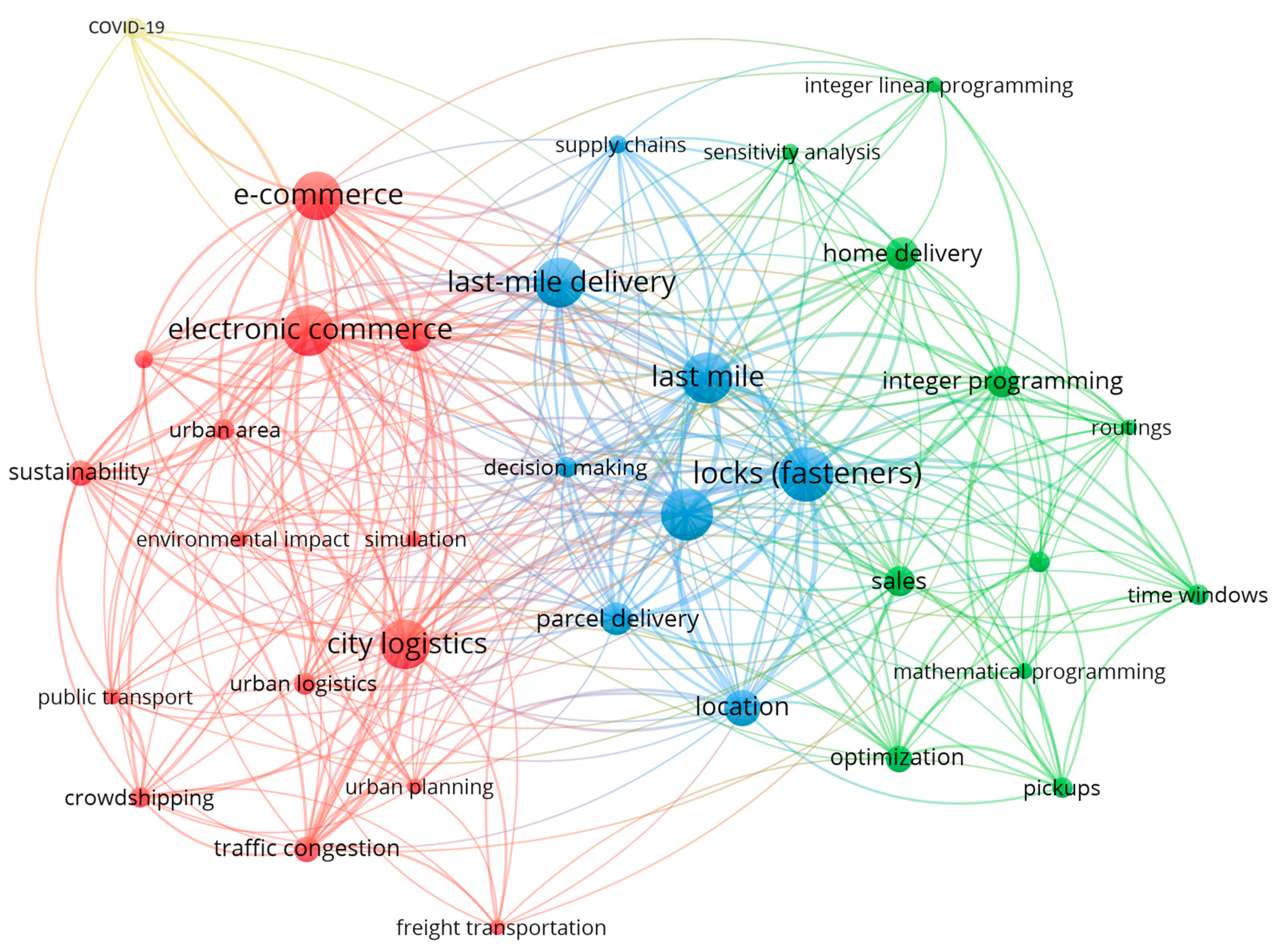

2. Scientific Literature Review

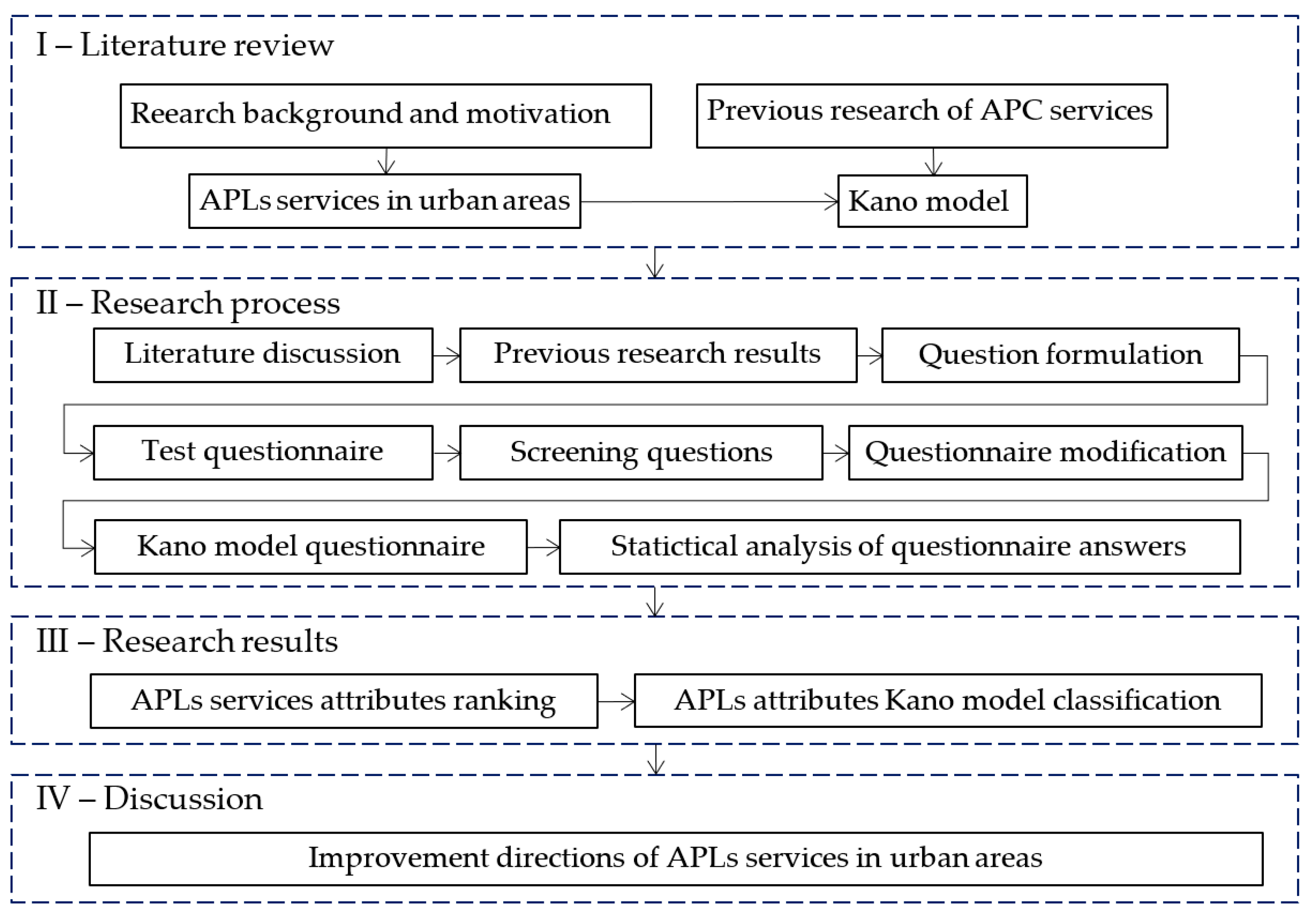

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Framework

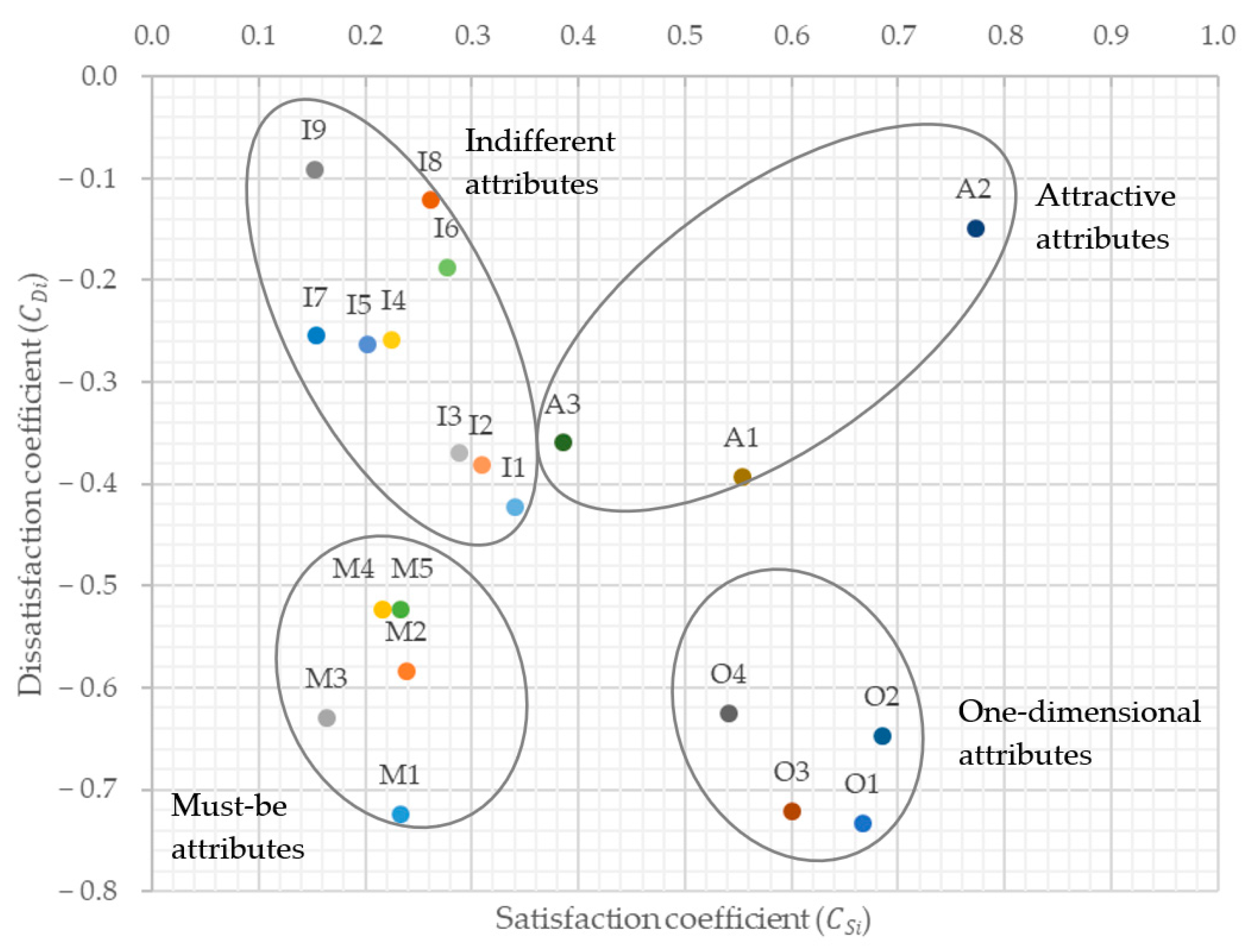

3.2. Kano Model

- Must-be attributes (M). This is a set of requirements that the recipient is not aware of, but they are extremely important from the perspective of shaping his satisfaction or dissatisfaction. This group is characterized by requirements whose fulfillment will not increase customer satisfaction, but their absence will result in customer dissatisfaction;

- One-dimensional attributes (O). This is a group of desired customer requirements. This means that their implementation increases satisfaction, but failure to meet these requirements will result in dissatisfaction;

- Attractive attributes (A). These are the service requirements meant to attract attention. Their fulfillment has a huge effect on increases in satisfaction, while their failure will affect the customer’s feelings.

- Indifferent attributes (I). The presence or absence of these requirements will in no way affect a return or reduction in customer satisfaction. They are irrelevant;

- Questionable attributes (Q). This is a group of requirements about which there is no reliable information on whether they are relevant to the consumer;

- Reverse attributes (R). These appear when the opposite of a given feature is important to the client.

- If (A + M + O) > (R + Q + I), then, finally, the category from groups A, M, or O with the highest value is selected;

- If (A + M + O) < (R + Q + I), then, finally, the category from the R, Q, or I group with the highest value is selected.

4. Results

- 24/7 customer support;

- Additional parcel locker services (e.g., refrigerated lockers, laundry services);

- Adjusting the size of the package to the size of the box (parameter related to problems with removing the parcel when the parcel tightly fills the box);

- Advertisements on parcel lockers;

- The convenience of receiving and sending parcels;

- Dedicated applications;

- The ease of use of the parcel locker;

- Improvements for people with disabilities;

- Methods of parcel pick-up (standard or automatically via smartphone);

- Methods of parcel drop-off (standard or online without the need to print the shipping label, which is attached by the courier upon receipt);

- Natural environment awareness;

- Parcel locker locations (related not only to a satisfactory distance but also to the place, for example, close to work or school);

- Parcel locker novelty (parameter related to modernity because newly created APLs sometimes differ from previous ones);

- Parcel locker service time (time needed for parcel pick-up or drop-off);

- Parking next to the parcel locker;

- Placing the parcel in a specific box (the service is called the easy access zone and enables users to place parcels in the lower compartments in the parcel locker);

- The possibility of using a multi-locker (allows users to pick up multiple parcels from multiple senders by one receiver or drop off multiple parcels to one receiver);

- Security of the parcel placed in the locker;

- Size of the parcel locker (number of boxes);

- Temperature inside;

- Time window for parcel pick-up.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APLs | Automated parcel lockers |

| APS | Automated parcel stations |

| BOPIL® | Buy Online, Pick-up in Locker |

| BOPIS | Buy Online, Pick-Up In-Store |

| COD | Cash on delivery |

| CPR | Consumer participation readiness |

| FMC | 15 min city |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MPL | Mobile parcel locker |

| NFC | Near-field communication |

| O2O | Online-to-offline |

| OC | Omnichannel |

| OOH | Out-of-home |

| PUDO | Pick Up Drop Off |

| SSTs | Self-service technologies |

References

- Chevalier, S. Global Retail e-Commerce Sales Worldwide from 2014 to 2026. Statista 2022, eMarketer. July 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/379046/worldwide-retail-e-commerce-sales/ (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Allen, J.; Piecyk, M.; Piotrowska, M.; McLeod, F.; Cherrett, T.; Ghali, K.; Nguyen, T.; Bektas, T.; Bates, O.; Friday, A.; et al. Understanding the impact of e-commerce on last-mile light goods vehicle activity in urban areas: The case of London. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 61, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, B.K.; Sarkar, M.; Chaudhuri, K.; Sarkar, B. Do you think that the home delivery is good for retailing? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Dey, B.K.; Sarkar, M.; AlArjani, A. A sustainable online-to-offline (O2O) retailing strategy for a supply chain management under controllable lead time and variable demand. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.B.; Dey, B.K.; Sarkar, B. Retailing and servicing strategies for an imperfect production with variable lead time and backorder under online-to-offline environment. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 2023, 19, 4804–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, A.; Holzapfel, A.; Kuhn, H. Distribution systems in omni-channel retailing. Bus. Res. 2016, 9, 255–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Thorne, G.; Browne, M. BESTUFS Good Practice Guide on Urban Freight Transport. 2007. Available online: https://www.eltis.org/sites/default/files/trainingmaterials/english_bestufs_guide.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Iwan, S.; Kijewska, K.; Lemke, J. Analysis of parcel lockers’ efficiency as the last mile delivery solution–the results of the research in Poland. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 12, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koncová, D.; Kremeňová, I.; Fabuš, J. Last Mile and its Latest Changes in Express, Courier and Postal Services Bound to E-commerce. Transp. Commun. 2022, 12, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakulenko, Y.; Hellström, D.; Hjort, K. What’s in the parcel locker? Exploring customer value in e-commerce last mile delivery. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPC. Annual Review 2020 Supporting Posts during the COVID-19 Crisis. Available online: https://www.ipc.be/sector-data/reports-library/ipc-reports-brochures/annual-review2020 (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Ducret, R. Parcel deliveries and urban logistics: Changes and challenges in the courier express and parcel sector in Europe—The French case. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 11, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, E.; Seidel, S.; Blanquart, C.; Dablanc, L.; Lenz, B. The impact of e-commerce on final deliveries: Alternative parcel delivery services in France and Germany. Transp. Res. Procedia 2014, 4, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InPost. Our History. Available online: https://inpost.eu/who-we-are/our-history (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Zurel, Ö.; Van Hoyweghen, L.; Braes, S.; Seghers, A. Parcel lockers, an answer to the pressure on the last mile delivery? In New Business and Regulatory Strategies in the Postal Sector; Spring: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PD CEN/TS 16819:2015; Postal Services. Parcel Boxes for End Use. Technical Features. The British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2015.

- Agatz, N.; Campbell, A.; Fleischmann, M.; Savelsbergh, M. Time slot management in attended home delivery. Transp. Sci. 2011, 45, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackert, J. Choice-based dynamic time slot management in attended home delivery. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 129, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahtafti, A.; Karimi, H.; Ardjmand, E.; Ghalehkhondabi, I. Time slot management in selective pickup and delivery problem with mixed time windows. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 159, 107512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otim, S.; Grover, V. An empirical study on web-based services and customer loyalty. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2006, 15, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.X.; Lu, G. Exploring the impact of delivery performance on customer transaction volume and unit price: Evidence from an assembly manufacturing supply chain. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2017, 26, 880–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garver, M.S.; Williams, Z.; Taylor, G.S.; Wynne, W.R. Modelling Choice in Logistics: A Managerial Guide and Application. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2012, 42, 128–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.H.; De Leeuw, S.; Dullaert, W.; Foubert, B.P. What is the right delivery option for you? Consumer preferences for delivery attributes in online retailing. J. Bus. Logist. 2019, 40, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Griffis, S.E.; Goldsby, T.J. Failure to deliver? Linking online order fulfillment glitches with future purchase behavior. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joerss, M.; Neuhaus, F.; Schröder, J. How customer demands are reshaping last-mile delivery. McKinsey Q. 2016, 17, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Popli, A.; Mishra, S. Factors of perceived risk affecting online purchase decisions of consumers. Pac. Bus. Rev. Int. 2015, 8, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Xu, M.; Xing, L. Exploring the core factors of online purchase decisions by building an E-Commerce network evolution model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P.; Joshi, H. Factors influencing online purchase intention towards online shopping of Gen Z. Int. J. Bus. Compet. Growth 2020, 7, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gelder, K. Factors That Influence Online Purchase Decisions in the United States and the United Kingdom in 2022. Statista. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/628782/internet-user-purchase-influence-factors/ (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Chen, C.F.; White, C.; Hsieh, Y.E. The role of consumer participation readiness in automated parcel station usage intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuter, M.L.; Ostrom, A.L.; Bitner, M.J.; Roundtree, R. The influence of technology anxiety on consumer use and experiences with self-service technologies. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, K.N.; Le, A.N.H.; Thanh Tam, L.; Ho Xuan, H. Immersive experience and customer responses towards mobile augmented reality applications: The moderating role of technology anxiety. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2063778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderman, C.J.; Paul, W.; Van Diemen, R. Choosing self-service technologies or interpersonal services—The impact of situational factors and technology-related attitudes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 18, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloulbi, A.; Öz, T.; Alzubi, A. The use of artificial intelligence for smart decision-making in smart cities: A moderated mediated model of technology anxiety and internal threats of IoT. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 6707431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X.; Ng, L.T.W.; Wong, Y.D. An investigation of customers’ intention to use self-collection services for last-mile delivery. Transp. Policy 2018, 66, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, L.G.; Vieira, J.G.V. An investigation of consumer intention to use pick-up point services for last-mile distribution in a developing country. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X.; Ma, F.; Wong, Y.D. The determinants of customers’ intention to use smart lockers for last-mile deliveries. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 49, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, A.; Kusumastuti, D.; Nicholson, A. Acceptability of collection and delivery points from consumers’ perspective: A qualitative case study of Christchurch city. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2017, 5, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, J.S.; Figliozzi, M.A. Spatial accessibility and equity analysis of Amazon parcel lockers facilities. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 97, 103212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Y.T.; Tiwasing, P. Customers’ intention to adopt smart lockers in last-mile delivery service: A multi-theory perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, Y.; Golany, B. A parcel locker network as a solution to the logistics last mile problem. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Lyu, J. Personal values as determinants of intentions to use self-service technology in retailing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milioti, C.; Pramatari, K.; Kelepouri, I. Modelling consumers’ acceptance for the click and collect service. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.K.; Morganti, E.; Dablanc, L.; de Oliveira, R.L.M. Analysis of the potential demand of automated delivery stations for e-commerce deliveries in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Res. Transp. Econ. 2017, 65, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, H.B.; Verlinde, S.; Macharis, C. Unlocking the failed delivery problem? Opportunities and challenges for smart locks from a consumer perspective. Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 87, 100753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.L.; Jang, H.; Fang, M.; Peng, K. Determinants of customer satisfaction with parcel locker services in last-mile logistics. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2022, 38, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H. Evaluating service quality of airline industry using hybrid best worst method and VIKOR. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 68, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shang, H. Service quality, perceived value, and citizens’ continuous-use intention regarding e-government: Empirical evidence from China. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, D. Analysis of the Level of Customer Service Quality on the Example of Inpost. Bachelor’s Thesis, Silesian University of Technology, Katowice, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Motyka, M. Research on the Preferences of Users of InPost Services in the Field of Self-Service Drop-Off and Pick-Up Points in the City of Żory. Bachelor’s Thesis, Silesian University of Technology, Katowice, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mosur, K. Analysis of the Quality Level of Courier Services on the Example of Inpost. Bachelor’s Thesis, Silesian University of Technology, Katowice, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kopała, P. Improving the Customer Service Process of Courier Services on the Example of InPost. Engineering Thesis, Silesian University of Technology, Katowice, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Czechowski, M. Testing the Quality of the Customer Service Process of Courier Services at the Sending and Receiving Points. Engineering Thesis, Silesian University of Technology, Katowice, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Naing, L.; Winn, T.B.N.R.; Rusli, B.N. Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Arch. Orofac. Sci. 2006, 1, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kano, N.; Seraku, N.; Takahashi, F.; Tsuji, S. Attractive quality and must-be quality. J. Jpn. Soc. Qual. Control. 1984, 14, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, C. Kano’s methods for understanding customer-defined quality. Cent. Qual. Manag. J. 1993, 2, 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Ji, P. Understanding customer needs through quantitative analysis of Kano’s model. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2010, 27, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulić, J.; Prebežac, D. A critical review of techniques for classifying quality attributes in the Kano model. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2011, 21, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witell, L.; Löfgren, M.; Dahlgaard, J.J. Theory of attractive quality and the Kano methodology–the past, the present, and the future. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2013, 24, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermanshachi, S.; Nipa, T.J.; Nadiri, H. Service quality assessment and enhancement using Kano model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobnina, M.; Rozhkov, A. Listening to the voice of the customer in the hospitality industry: Kano model application. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Srivastava, R.K. Customer satisfaction for designing attractive qualities of healthcare service in India using Kano model and quality function deployment. MIT Int. J. Mech. Eng. 2011, 1, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, F.Y.; Yeh, T.M.; Tang, C.Y. Classifying restaurant service quality attributes by using Kano model and IPA approach. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2018, 29, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.J.; Yeh, T.M.; Pai, F.Y.; Chen, D.F. Integrating refined kano model and QFD for service quality improvement in healthy fast-food chain restaurants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, L.; Dong, Y. Research on innovative design of community mutual aid elderly care service platform based on Kano model. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, M.; Kim, H.B. User acceptance of hotel service robots using the quantitative kano model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A.; Pourhamidi, M.; Antony, J.; Hyun Park, S. Typology of Kano models: A critical review of literature and proposition of a revised model. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2013, 30, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.H. Application of Refined Kano’s Model to Shoe Production and Consumer Satisfaction Assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schvaneveldt, S.J.; Enkawa, T.; Miyakawa, M. Consumer evaluation perspectives of service quality: Evaluation factors and two-way model of quality. Total Qual. Manag. 1991, 2, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Hinterhuber, H.H. How to make product development projects more successful by integrating Kano’s model of customer satisfaction into quality function deployment. Technovation 1998, 18, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A.; Mohammadi Shahiverdi, S. Estimating customer lifetime value for new product development based on the Kano model with a case study in automobile industry. Benchmarking Int. J. 2015, 22, 857–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Jiao, R.J.; Yang, X.; Helander, M.; Khalid, H.M.; Opperud, A. An analytical Kano model for customer need analysis. Des. Stud. 2009, 30, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.M.; Chau, K.Y.; Xu, D.; Liu, X. Consumer perceptions to support IoT based smart parcel locker logistics in China. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederprüm, A.; van Lienden, W. Parcel Locker Stations: A Solution for the Last Mile? (No. 2). WIK Working Paper. 2021. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/253743/1/WIK-WP-No2.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Akdoğan, K.; Özceylan, E. Parcel Locker Applications in Turkey. Beykent Üniversitesi Fen Ve Mühendislik Bilim. Derg. 2023, 16, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, M. Automated parcel terminals-commercialization of the system for automated post services. Известия На Съюза На Учените-Варна. Серия Икoнoмически Науки 2022, 11, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.F.; Luo, R.J.; Peng, X.S. A probability guided evolutionary algorithm for multi-objective green express cabinet assignment in urban last-mile logistics. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 3382–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagorio, A.; Pinto, R. The parcel locker location issues: An overview of factors affecting their location. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Information Systems, Logistics and Supply Chain: Interconnected Supply Chains in an Era of Innovation, Austin, TX, USA, 22–24 April 2020; pp. 414–421. [Google Scholar]

- Wróbel-Jędrzejewska, M.; Polak, E. The operation analysis of the innovative MainBox food storage device. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.S.; Park, A.; Song, J.M.; Chung, C. Consumers’ adoption of parcel locker service: Protection and technology perspectives. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2144096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Yu, T.S.; Lim, S.J. An Unmanned Smart Parcel Locker System with a Parcel Sterilizer. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2021, 18, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, C.C.; Liang, C.H.; Sham, R. The effectiveness of parcel locker that affects the delivery options among online shoppers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2022, 41, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Lorente, J.; Gabor, A.F.; Ponce-Cueto, E. Omnichannel logistics network design with integrated customer preference for deliveries and returns. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 144, 106433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, P.; Veldman, R.; Zhang, Y. Universal Locker Systems for urban areas. In Proceedings of the 53rd ORSNZ Annual Conference, December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lachapelle, U.; Burke, M.; Brotherton, A.; Leung, A. Parcel locker systems in a car dominant city: Location, characterisation and potential impacts on city planning and consumer travel access. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 71, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bi, M.; Lai, J.; Chen, Y. Locating movable parcel lockers under stochastic demands. Symmetry 2020, 12, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdfeger, S.; Boysen, N. Who moves the locker? A benchmark study of alternative mobile parcel locker concepts. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 142, 103780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarević, D.; Dobrodolac, M.; Marković, D. Implementation of Mobile Parcel Lockers in Delivery Systems–Analysis by the AHP Approach. Int. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2023, 13, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tested attitude | Positive variant |

|

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Negative variant |

| |

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

| Tested Attitude | Negative Variant | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) I Like It That Way | (2) It Must Be That Way | (3) I Am Neutral | (4) I Can Live with It That Way | (5) I Dislike It That Way | ||

| Positive variant |

| Q | A | A | A | O |

| R | I | I | I | M | |

| R | I | I | I | M | |

| R | I | I | I | M | |

| R | R | R | R | Q | |

| Attribute | Proportion of Each Type of Kano Quality Attribute (%) | Classification Type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | O | A | I | Q | R | ||

| 24/7 customer support | 20.52 | 5.13 | 14.53 | 57.25 | 0.86 | 1.71 | I |

| Additional APL services | 11.11 | 35.89 | 6.87 | 10.26 | 3.42 | 32.48 | O |

| Adjusting the size of the package to the size of the box | 54.70 | 7.69 | 8.55 | 28.21 | 0.00 | 0.85 | M |

| Advertisements on APLs | 19.66 | 15.38 | 12.82 | 35.04 | 1.71 | 15.38 | I |

| Convenience of receiving and sending parcels | 7.69 | 5.13 | 61.54 | 11.97 | 2.56 | 11.11 | A |

| Dedicated applications | 57.26 | 14.53 | 8.55 | 18.80 | 0.00 | 0.85 | M |

| Ease of use of APLs | 19.66 | 31.62 | 12.82 | 17.95 | 0.00 | 17.95 | O |

| Improvements for people with disabilities | 30.77 | 7.69 | 15.38 | 45.30 | 0.00 | 0.85 | M |

| Methods of parcel pick-up | 24.79 | 10.26 | 27.35 | 35.04 | 0.85 | 1.71 | A |

| Methods of parcel drop-off | 7.69 | 3.42 | 20.51 | 59.83 | 6.84 | 1.71 | I |

| Natural environment awareness | 19.66 | 5.98 | 16.24 | 57.26 | 0.00 | 0.85 | I |

| Parcel locker location | 42.74 | 6.84 | 13.68 | 31.62 | 2.56 | 2.56 | M |

| Parcel locker novelty | 15.38 | 19.66 | 7.69 | 52.14 | 0.85 | 4.27 | I |

| Parcel locker service time | 21.37 | 16.24 | 36.75 | 21.37 | 1.71 | 2.56 | A |

| Parking next to APL | 18.80 | 52.14 | 6.84 | 20.51 | 0.00 | 1.71 | O |

| Placing the parcel in a specific box | 43.59 | 12.82 | 10.26 | 29.91 | 0.85 | 2.56 | M |

| Possibility of using a multi-locker | 20.51 | 11.11 | 14.53 | 36.75 | 1.71 | 15.38 | I |

| Security of the parcel placed in the APL | 14.53 | 43.59 | 17.95 | 13.68 | 2.56 | 7.69 | O |

| Size of the APL | 11.11 | 6.84 | 19.66 | 58.12 | 0.00 | 4.27 | I |

| Temperature inside the APL | 19.66 | 4.27 | 10.26 | 59.83 | 3.42 | 2.56 | I |

| Time window for parcel pick-up | 5.98 | 1.71 | 11.11 | 64.96 | 2.56 | 13.68 | I |

| Classification Type | Attribute | Satisfaction Coefficient () | Dissatisfaction Coefficient () | Total Satisfaction Index | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Must-be (M) | Dedicated application | 0.2328 | −0.7241 | −0.9569 | 1 |

| Placing the parcel in a specific box | 0.2389 | −0.5841 | −0.8230 | 2 | |

| Adjusting the size of the package to the size of the box | 0.1638 | −0.6293 | −0.7931 | 3 | |

| Parcel locker location | 0.2162 | −0.5225 | −0.7387 | 4 | |

| Improvements for people with disabilities | 0.2328 | −0.3879 | −0.6207 | 5 | |

| One-dimensional (O) | Additional APL services | 0.6667 | −0.7333 | −1.4000 | 1 |

| Security of the parcel placed in APL | 0.6857 | −0.6476 | −1.3333 | 2 | |

| Parking next to APL | 0.6000 | −0.7217 | −1.3217 | 3 | |

| Ease of use of APLs | 0.5417 | −0.6250 | −1.1667 | 4 | |

| Attractive (A) | Parcel locker service time | 0.5536 | −0.3929 | 0.9464 | 1 |

| Convenience of receiving and sending parcels | 0.7723 | −0.1485 | 0.9208 | 2 | |

| Methods of the parcel pick-up | 0.3860 | −0.3596 | 0.7456 | 3 | |

| Indifferent (I) | Advertisements on APLs | 0.3402 | −0.4227 | −0.7629 | 1 |

| Possibility of using a multi-locker | 0.3093 | −0.3814 | −0.6907 | 2 | |

| Parcel locker novelty | 0.2883 | −0.3694 | −0.6577 | 3 | |

| Natural environment awareness | 0.2241 | −0.2586 | −0.4828 | 4 | |

| 24/7 customer support | 0.2018 | −0.2632 | −0.4649 | 5 | |

| Size of the APL | 0.2768 | −0.1875 | −0.4643 | 6 | |

| Temperature inside | 0.1545 | −0.2545 | −0.4091 | 7 | |

| Methods of parcel drop-off | 0.2617 | −0.1215 | −0.3832 | 8 | |

| Time window for parcel pick-up | 0.1531 | −0.0918 | −0.2449 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cieśla, M. Perceived Importance and Quality Attributes of Automated Parcel Locker Services in Urban Areas. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 2661-2679. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities6050120

Cieśla M. Perceived Importance and Quality Attributes of Automated Parcel Locker Services in Urban Areas. Smart Cities. 2023; 6(5):2661-2679. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities6050120

Chicago/Turabian StyleCieśla, Maria. 2023. "Perceived Importance and Quality Attributes of Automated Parcel Locker Services in Urban Areas" Smart Cities 6, no. 5: 2661-2679. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities6050120

APA StyleCieśla, M. (2023). Perceived Importance and Quality Attributes of Automated Parcel Locker Services in Urban Areas. Smart Cities, 6(5), 2661-2679. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities6050120