Beyond Digestion: The Gut Microbiota as an Immune–Metabolic Interface in Disease Modulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Gut Microbiota and Microecology

1.2. Microbial Diversity and Composition of Gut Microbiota

1.2.1. Diversity and Complexity

1.2.2. Composition and Variability

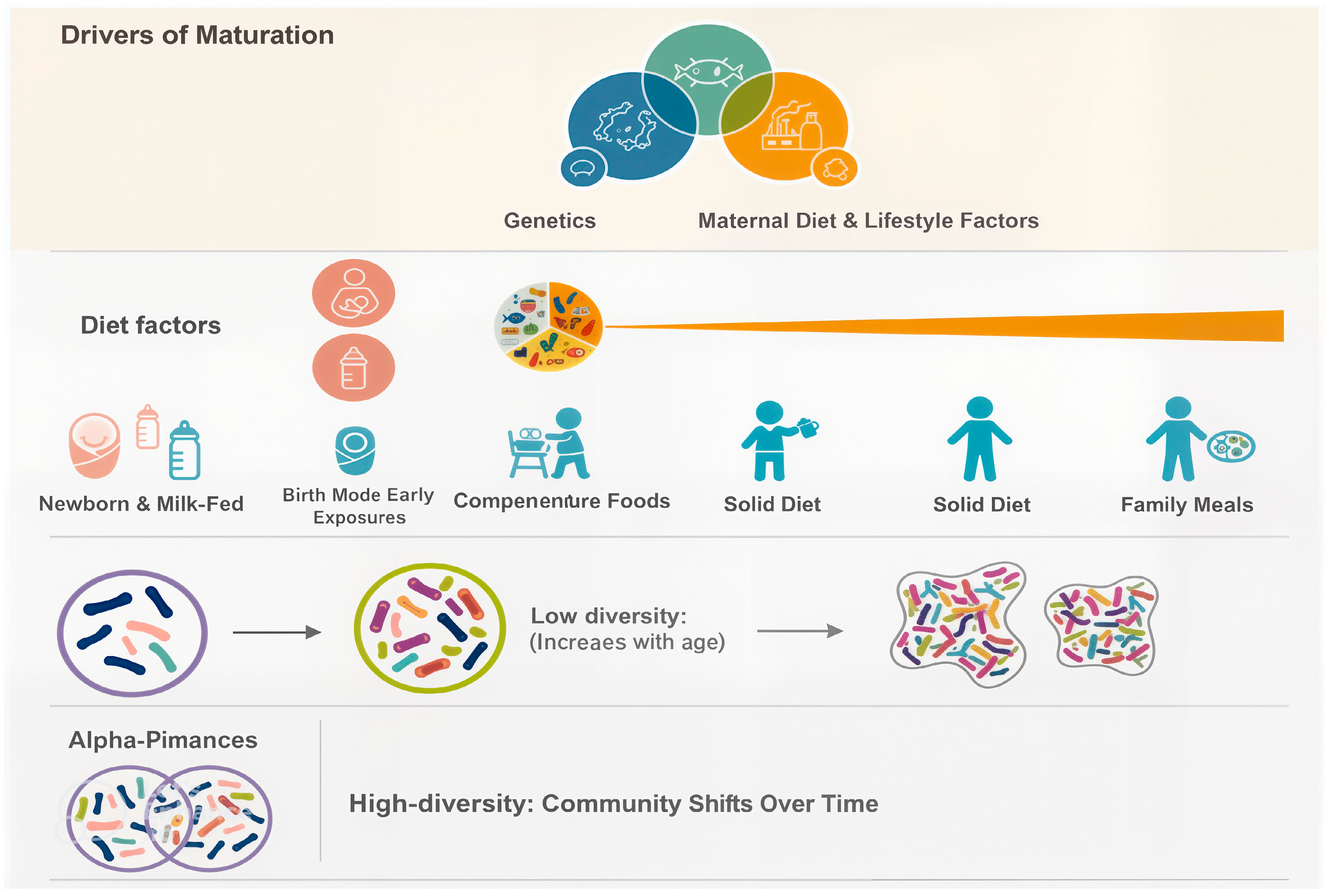

- Diet: Nutrient intake influences microbial diversity; fiber-rich diets promote beneficial bacteria, while high-fat or processed diets encourage the growth of potentially pathogenic species.

- Age: The microbiome undergoes dynamic shifts across the human lifespan, from infancy to old age.

- Antibiotic Use: Antibiotics can profoundly disrupt microbial balance, decreasing diversity and promoting dysbiosis.

- Environmental Exposures: Factors such as geography, hygiene, lifestyle, and contact with animals impact microbial acquisition and composition.

1.3. Aims and Significance of Microbiome Research

- Understanding Disease Mechanisms: Investigating how microbial communities influence the onset and progression of diseases.

- Developing Therapeutic Strategies: Exploring the potential of probiotics, prebiotics, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), and microbial-based drug formulations for gut microbiota modulation [14].

- Advancing Precision Medicine: Integrating microbiome profiles with metagenomics and multi-omics technologies to develop personalized healthcare strategies.

- Identifying Research Gaps: Synthesizing current knowledge to illuminate areas requiring further investigation and innovation.

- Enhancing Cancer Treatment: Studying how the gut microbiota affects the tumor microenvironment and modulates the efficacy of immunotherapy and chemotherapy in patients.

1.4. Conceptual Framework

2. Composition and Functional Diversity of the Gut Microbiota

2.1. Significant Microbial Phyla

2.2. Functions of the Gut Microbiota

2.2.1. Nutrient Metabolism and SCFA Production

| Microbial Factor/Species | Immune–Metabolic Function | Disease Context/Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Produces butyrate and anti-inflammatory metabolites; induces IL-10 and Treg cells; suppresses NF-κB signaling. | Mitigates colitis inflammation and enhances gut barrier integrity. | [19,20] |

| F. prausnitzii (live strain) | Reduces expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12); inhibits IL-8 via NF-κB | Reduces severity in patients with IBD, stabilizes gut homeostasis | [13] |

| Akkermansia muciniphila | Supports mucosal integrity; modulates metabolic inflammation. | Linked to improved obesity and metabolic health outcomes | [21,22] |

| SCFAs & metabolites (Butyrate) | Signal through GPCRs; support gut barrier, immune balance, and systemic metabolism; Inhibits histone deacetylases (HDACs). | Protective for patients with asthma, IBD, and colon inflammation, systemic inflammation. | [18,23] |

| Bacteroides species (e.g., B. uniformis) | Ferment carbohydrates into acetate/propionate; regulate gut microenvironment and metabolism. | Potential obesity alleviation and immune modulation in patients. | [24] |

| Dysbiosis (Microbial Imbalance) | Loss of beneficial organisms, overgrowth of pathobionts, reduced diversity (Figure 1). | Associated with patients with IBD, obesity, cancer, and neuro-inflammation. | [20,25] |

2.2.2. Immune System Modulation

2.2.3. Protection Against Pathogens

2.2.4. Gut–Organ Communication Axes

- Gut–Brain Axis:The gut–brain axis represents a complex, bidirectional communication system that operates through neural, hormonal, metabolic, and immune pathways. Gut microbes synthesize a variety of neuroactive compounds, including serotonin, dopamine precursors, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and short-chain fatty acids [25], all of which influence gastrointestinal motility, stress response, mood regulation, and cognitive processes. Disruptions in this axis have been linked to neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. For example, alterations in microbial composition have been associated with heightened risk of Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease, where gut-derived signals may influence neuroinflammation and protein aggregation in the brain [33].

- Gut–Liver Axis:The liver and gut are intimately connected, as nearly 70% of hepatic blood flow is supplied directly from the gut via the portal vein. This anatomical relationship exposes the liver to microbial metabolites and components such as lipopolysaccharides (LPSs), peptidoglycans, and bile acids. The gut microbiota plays a critical role in bile acid metabolism, which in turn modulates immune cell function in the liver, particularly natural killer T (NKT) cells [34]. Interestingly, primary bile acids can support protective immune activity and even suppress tumor growth by enhancing NKT responses, while secondary bile acids, produced by microbial transformation, may contribute to chronic inflammation and carcinogenesis. This delicate balance illustrates how gut–liver interactions can determine outcomes ranging from metabolic homeostasis to liver disease progression [35].

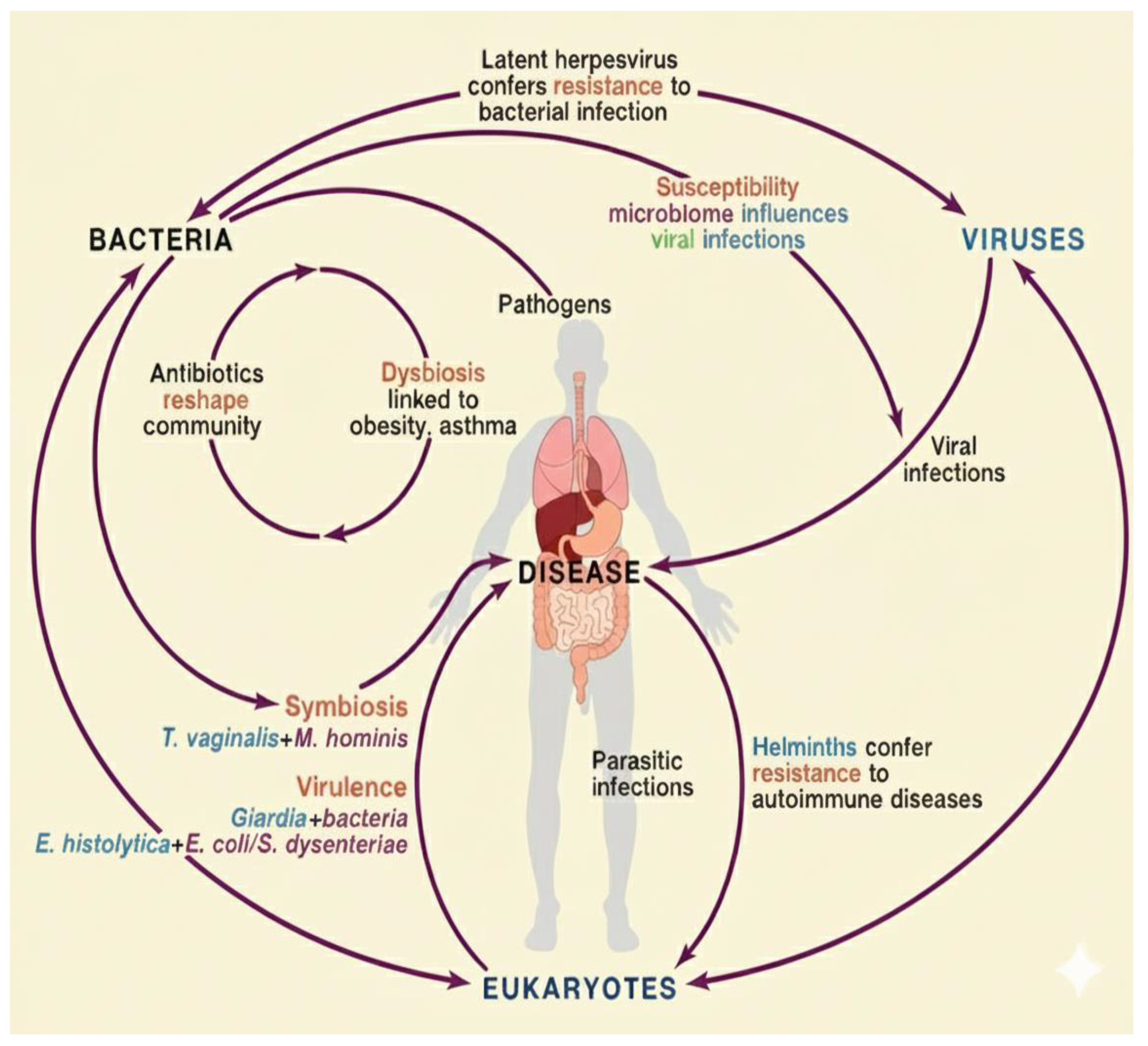

- Gut–Skin Axis:The relationship between the gut microbiota and skin health has gained increasing attention, especially in the context of chronic inflammatory skin conditions. Dysbiosis in the gut can lead to systemic immune dysregulation (Figure 2), increased intestinal permeability, and circulation of pro-inflammatory metabolites that affect skin physiology [36]. Conditions such as psoriasis, rosacea, and atopic dermatitis have all been linked to gut microbial imbalances. Likewise, gut-derived metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids, can influence skin barrier integrity, hydration, and immune responses, underscoring the systemic nature of microbial communication. These insights highlight that maintaining gut microbial balance is not only essential for internal organ function but also for visible markers of health such as skin integrity and appearance [37].

2.3. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Human Health

2.3.1. The Microbiota as a Central Regulator of Host Physiology

2.3.2. Key Functional Contributions

- I. Nutrient Absorption and Metabolism: Gut microbes facilitate the breakdown of dietary fibers and complex carbohydrates, leading to SCFA production, which fuels colonocytes, modulates immune signaling, and contributes to anti-inflammatory processes [42].

- II. Immune System Modulation: The gut microbiota plays a critical role in educating and shaping the host immune system. It stimulates the secretion of protective mucins and antimicrobial peptides while also fostering immune tolerance to harmless antigens. Through interactions with macrophages, dendritic cells, and regulatory T cells (Tregs), commensal microbes ensure a balanced immune response that is effective against pathogens but restrained enough to prevent excessive inflammation or autoimmunity. This immunomodulatory role is central to preventing conditions such as allergies, autoimmune diseases, and chronic inflammatory disorders [43].

- III. Barrier Integrity and Pathogen Defense: Commensal microbes maintain the gut mucosal barrier and inhibit pathogenic overgrowth by producing antimicrobial peptides and modifying the intestinal environment [44].

- IV. Xenobiotic and Drug Metabolism: Gut microbes also influence the fate of therapeutic drugs and xenobiotics. Microbial enzymes can activate, deactivate, or even toxify pharmaceutical compounds, thereby altering their bioavailability and efficacy. For example, certain bacteria metabolize digoxin, reducing its therapeutic effect, while others enhance the activity of specific chemotherapeutic agents [45].

2.4. Importance of Gut Microbiota Balance

3. Microbiota–Immune and Metabolic Interactions

3.1. Overview of Host–Microbiota Interactions

3.2. Immune System Crosstalk

- Recognition of Microbial Signals: The host immune system detects microbial presence via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NOD-like receptors (NLRs). These receptors recognize microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), flagellin, and peptidoglycans, initiating tailored immune responses that distinguish between beneficial commensals and potential pathogens [50].

- Mucosal Immunity: Commensal microbes actively promote the secretion of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), immunoglobulin A (IgA), and mucus, forming a multifaceted defense that protects against invading pathogens while maintaining immune tolerance to harmless microbes. These mechanisms establish a controlled environment that balances protection with symbiosis [51].

- Immune Homeostasis: Gut microbial signals modulate the equilibrium between pro-inflammatory and regulatory pathways. They influence the differentiation and function of T cells—including regulatory T cells (Tregs)—as well as dendritic cells and macrophages, shaping immune responses that are precise and proportionate [52].

3.3. Gut Barrier Integrity

3.4. Microbial Metabolites and Host Physiology

- Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): Fermentation of dietary fibers generates SCFAs—primarily butyrate, acetate, and propionate—that serve as energy sources for colonocytes, modulate immune signaling (e.g., Treg differentiation), and strengthen epithelial barrier function [55].

- Bile Acid Metabolites: Microbial transformation of primary bile acids into secondary bile acids influences lipid metabolism, immune pathways, and hepatic function through receptors such as FXR and TGR5. These metabolites play key roles in the gut–liver axis and in systemic metabolic regulation [56].

- Tryptophan Derivatives: Indole and related compounds activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), contributing to mucosal immunity, epithelial repair, and modulation of inflammatory responses [57].

- Vitamins: Certain gut bacteria synthesize essential vitamins, including vitamin K and B-group vitamins, supporting coagulation, DNA synthesis, energy metabolism, and overall cellular function [58].

3.5. Host Regulation of Microbiota

- Diet: Macronutrient composition and fiber intake strongly influence microbial diversity and metabolic activity. High-fiber diets enrich SCFA-producing bacteria, while high-fat or low-fiber diets may promote dysbiosis and inflammation [59].

- Immune Regulation: Host defenses, including IgA secretion, antimicrobial peptide production, and continuous epithelial renewal, maintain microbial balance and prevent overgrowth of potentially harmful organisms.

- Medications: Antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), proton pump inhibitors, and other pharmaceuticals can disrupt microbial ecosystems, often leading to reduced diversity and altered metabolic outputs [60].

- Environmental and Lifestyle Factors: Urbanization, stress, hygiene practices, toxin exposure, and early-life microbial exposures shape the microbiota, influencing immune development and long-term health outcomes.

- Genetic Background: Host genetics determine susceptibility to microbial colonization, immune responsiveness, and predisposition to dysbiosis, highlighting the interplay between hereditary factors and microbial ecology [21].

4. Gut Microbial Symbiosis and the Health Consequences of Dysbiosis

4.1. The Functional Benefits of Gut Symbiosis

4.1.1. Nutrient Metabolism and Energy Production

- Energy Supply: Butyrate acts as a primary energy source for colonocytes, supporting epithelial health and promoting efficient nutrient absorption.

- Immune Modulation: SCFAs influence the differentiation and function of immune cells, including regulatory T cells, helping to maintain a balanced inflammatory response [62].

- Metabolic Regulation: These metabolites play key roles in lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis, contributing to overall energy balance and metabolic health.

4.1.2. Immune System Development and Regulation

- Promotion of Immune Tolerance: Commensal microbes prevent excessive immune activation, reducing the risk of chronic inflammation and autoimmune responses.

- Modulation of Regulatory T Cells (Tregs): Microbial signals influence the differentiation and function of Tregs, which are critical for maintaining immune homeostasis and controlling inflammatory responses [64].

- Production of Immunoregulatory Metabolites: Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) ligands, and polyamines produced by gut bacteria serve as signaling molecules that fine-tune immune responses, support mucosal integrity, and regulate inflammatory pathways.

4.1.3. Maintenance of Gut Barrier Integrity and Pathogen Defense

- Competitive Exclusion: Beneficial microbes occupy ecological niches within the gut, consuming available nutrients and adhering to mucosal surfaces. This limits the ability of pathogenic organisms to colonize and establish infections [65]).

- Induction of Antimicrobial Peptides and Mucin Production: Gut bacteria stimulate the secretion of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and mucus, creating both chemical and physical barriers that inhibit pathogen growth and adherence to the epithelium [66].

- Reinforcement of Epithelial Tight Junctions: Microbial signals enhance the expression and assembly of tight junction proteins, strengthening the epithelial barrier. This reduces intestinal permeability, prevents the translocation of pathogens and toxins into the systemic circulation, and mitigates inflammation [67].

4.1.4. Gut–Brain Axis and Mental Health

- Production of Neuroactive Compounds: Gut microbes synthesize and modulate the availability of neuroactive molecules, including gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotonin precursors, dopamine intermediates, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). These compounds can directly or indirectly affect neurotransmission, mood, and cognitive processes [69].

- Regulation of Neuro-inflammation: Microbial signals influence neuroimmune pathways, modulating microglial activation and inflammatory responses within the brain. This interaction can impact susceptibility to neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative conditions [70].

- Implications for Mental Health: Dysbiosis and alterations in microbial composition have been linked to mood disorders such as depression and anxiety, as well as neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Gut microbial balance, therefore, emerges as a potential target for therapeutic interventions aimed at improving mental and neurological health [71].

4.1.5. Metabolite Production and Systemic Regulation

- Regulation of Systemic Inflammation: Microbial metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), indole derivatives, and polyamines, modulate immune cell activity and cytokine production. This helps maintain a balanced inflammatory state, preventing chronic low-grade inflammation that is implicated in metabolic, cardiovascular, and autoimmune diseases [73].

- Modulation of Hepatic Metabolism and Energy Balance: Gut-derived metabolites, such as secondary bile acids and SCFAs, interact with hepatic receptors like FXR and TGR5 to regulate lipid and glucose metabolism, energy homeostasis, and insulin sensitivity. These interactions link microbial activity to systemic metabolic health [74].

- Alteration of the Tumor Microenvironment (TME): Microbial metabolites can influence the immune landscape within the TME of patients by modulating cytokine profiles, immune cell infiltration, and local inflammation. Such effects may either suppress or promote tumor progression and can impact the efficacy of chemotherapy and immunotherapy, highlighting the microbiota’s role in cancer biology [75].

4.1.6. Drug Metabolism and Therapeutic Response

- Activation or Inactivation of Therapeutic Agents: Certain gut bacteria can chemically modify drugs, either activating prodrugs into their therapeutically active forms or inactivating medications, thereby reducing their effectiveness.

- Modification of Drug Pharmacokinetics: Microbial activity can influence drug absorption in the gut, affect systemic half-life, and alter elimination pathways. This can result in variations in drug concentration and therapeutic outcomes among individuals [45].

- Regulation of Host Metabolic Pathways: The microbiota can modulate the expression of host metabolic enzymes and transporters, further shaping drug metabolism and response.

4.1.7. Modulation of the Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

- Cytokine Regulation and Immune Infiltration: Commensal microbes and their metabolites influence the production of cytokines such as IL-10, IL-17, and IFN-γ, which in turn regulate the recruitment and activation of immune cells including T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and dendritic cells within the TME [45].

- Inflammation Control: Depending on microbial composition, the microbiota can suppress chronic low-grade inflammation that promotes tumor growth or, conversely, exacerbate pro-inflammatory pathways that support cancer progression [76].

- Therapeutic Modulation: Specific bacterial species have been shown to enhance the efficacy of conventional therapies in patients, such as chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), by improving antigen presentation, T-cell activation, and overall immune responsiveness [77].

4.2. Gut Dysbiosis: Etiology and Clinical Consequences

4.2.1. Definition and Causes

- Dietary Factors

- High-fat, low-fiber diets reduce beneficial microbial species.

- Medical Interventions.

- Antibiotic overuse, chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation alter gut ecology.

- Pathological Conditions.

- Chronic inflammation and infections drive dysbiosis.

- Environmental & Lifestyle Stressors.

- Toxins and psychological stress impact microbial function and host resilience.

4.2.2. Disease Associations

- Inflammatory DisordersIn Patients with IBD, depletion of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and expansion of adherent-invasive E. coli drive mucosal inflammation. Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) are linked to reduced Bifidobacterium and Lacticaseibacillus casei, causing increased permeability and visceral hypersensitivity. Psoriasis is associated with loss of SCFA producers and immune imbalance [19,20].

- Cancer and Tumor ProgressionDysbiosis promotes oncogenic inflammation and immune evasion. Fusobacterium nucleatum is strongly linked to colorectal cancer progression in patients. Microbial composition also shapes response to chemotherapy and immunotherapy [78].

- Metabolic DisordersIn patients with obesity, a higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio enhances energy harvest. In Type 2 Diabetes, reduced diversity and SCFAs contribute to insulin resistance and inflammation.

- Neuropsychiatric DisordersDysbiosis alters neurotransmitter synthesis and neuroimmune signaling, contributing to depression, anxiety, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s [79].

- Drug Metabolism and Therapy ResponseAntibiotic-induced dysbiosis reduces the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors, while altered microbial enzymes impair drug metabolism and treatment outcomes.

5. Microbiota-Derived Metabolites and Therapeutic Implications

5.1. Prebiotics

- Fermentation of prebiotics yields short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including butyrate and propionate, which regulate inflammation, improve epithelial integrity, and exert systemic immunomodulatory effects [55].

- Prebiotic intake has been associated with metabolic improvements, including enhanced insulin sensitivity and body weight regulation in overweight individuals.

- In oncology, dietary fiber and ginseng polysaccharides have been shown to augment PD-1 blockade efficacy by suppressing regulatory T cells (Tregs) and activating cytotoxic T cells within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [74].

- Efficacy depends on the presence of specific microbial taxa; without a sufficient baseline population of target microbes, prebiotics may yield minimal benefit.

5.2. Probiotics

- Predominantly from the genera Lacticaseibacillus casei, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, Limosilactobacillus reuteri and Bifidobacterium, probiotics can modulate the microbiota, enhance epithelial barrier integrity, produce antimicrobial compounds, and regulate host immune responses [20].

- Clinical applications span a range of Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), antibiotic-associated diarrhea, and even neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression [53].

- Bifidobacterium infantis has demonstrated the symptom of relief in patients with IBS, while certain strains are linked to remission maintenance in patients with ulcerative colitis (though less effective in patients with Crohn’s disease) [19].

- In the context of cancer immunotherapy for the patient, probiotics may enhance immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) efficacy by restoring microbial diversity and promoting immune activation.

- Next-generation probiotics (NGPs), such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Akkermansia muciniphila, are being developed for precision microbiome therapies due to their endogenous origin and anti-inflammatory potential [13].

5.3. Synbiotics

- These formulations improve microbial resilience and host–microbe interactions, especially in gastrointestinal and metabolic diseases.

- Synbiotics have demonstrated efficacy in reducing the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates and lowering blood pressure in hypertensive patients [59].

- In patients with ulcerative colitis, combinations such as Bifidobacterium breve with GOS have yielded improved clinical outcomes.

- Emerging evidence suggests synbiotics may augment the therapeutic response to ICBs in hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating the TME.

5.4. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

- Rigorous donor screening is essential, excluding individuals with a personal or familial history of autoimmune, metabolic, or oncologic conditions.

- Delivery routes include colonoscopy, enema, nasoduodenal tubes, and encapsulated oral formulations.

- FMT is an established treatment for patients with repeated Clostridioides difficile infections, and it is under investigation for a wide range of conditions, including patients with IBD, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), hepatic encephalopathy, multiple sclerosis, autism, and metabolic syndrome [19].

- In oncology, FMT has been shown to modulate tumor-resident microbiota, enhance systemic and intratumoral immune responses, and improve responses to ICB therapy, particularly when derived from donors who previously responded favorably to immunotherapy [75].

- Potential mechanisms include the regulation of intestinal and circulating miRNAs, metabolic remodeling, and TME reprogramming.

- Challenges include inter-individual variability in response, uncertainty about long-term efficacy, and logistical complexities regarding donor matching, route of administration, and frequency of delivery.

5.5. Dietary Modifications

- High-fiber diets promote saccharolytic fermentation and SCFA production, which support mucosal health and anti-inflammatory pathways [55].

- Polyphenols—bioactive compounds in fruits, vegetables, tea, and wine exhibit prebiotic properties and contribute to microbial diversity [80].

- Fermented foods, including yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and kimchi, introduce live microbial cultures that reinforce microbial resilience and immune tolerance [80].

- Dietary strategies have been linked to cancer prevention in patients, improved gut barrier function, and enhanced responsiveness to cancer therapies [81].

- Personalized dietary interventions, based on individual microbial profiles, may further optimize outcomes.

5.6. Microbiome-Based Drug Development

- Engineered probiotics can be programmed to secrete bioactive compounds, degrade immunosuppressive molecules, modulate immune checkpoints, or deliver tumor-specific antigens.

- Bacteria equipped with CRISPR-based genome editing or type III secretion systems (T3SS) enable targeted interventions within the host or tumor microenvironment [82].

- Microbiome-based approaches can also influence systemic drug metabolism, thereby modulating pharmacokinetics and improving therapeutic indices.

- Bacteriophage therapy offers a precise method to selectively eliminate pathogenic strains without disrupting commensal microbiota [83].

- These tools offer highly specific, customizable treatments but require stringent safety evaluations and regulatory frameworks prior to clinical application.

6. Gut Microbiota in Cancer and Immunotherapy

6.1. Influence on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs) and Immunotherapy Response

6.2. Key Bacteria Associated with Improved Cancer Treatment Outcomes

- Akkermansia muciniphila: Enhances ICI efficacy and lymphocyte infiltration.

- Bifidobacterium spp.: Improve anti-PD-1 therap=y, especially in breast cancer models [87].

- Lachnospiraceae and Alistipes: Linked with longer survival in Patients with HCC.

- Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: Supports anti-PD-L1 therapy through butyrate production [88].

- Other commensals (Collinsella, Enterococcus, Blautia) support immune homeostasis.

6.3. Role of Microbial Metabolites in Tumor Progression and Therapy

- SCFAs strengthen the gut barrier and limit tumor angiogenesis.

- Inosine boosts anti-PD-L1 therapy effectiveness [89].

- Hydrogen sulfide and bile acids promote DNA damage and colorectal cancer.

- Indole derivatives (e.g., 3-IAA) modulate chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer.

6.4. Antibiotic Impact on Cancer Therapy

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics cause dysbiosis and weaken immune responses.

- Antibiotic use during ICI therapy lowers survival and response rates.

- Disruption of gut balance increases intestinal permeability and inflammation.

- Germ-free or antibiotic-treated mice show poor chemotherapy outcomes.

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Immune Effects | Metabolic Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotics (Bifidobacterium, Lacticaseibacillus casei, Akkermansia) | Enhance gut barrier, modulate cytokine production, compete with pathogens | Increase Treg activation, reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α), promote antitumor immunity in patients | Improve insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism, and SCFA production. | [91] |

| Prebiotics (inulin, resistant starch, fibers) | Provide substrates for beneficial microbes, increase SCFA production | Promote anti-inflammatory immune responses; enhance IgA secretion in patients | Boost SCFA levels (butyrate, propionate), improve glucose and lipid metabolism. | [92] |

| Synbiotics (Probiotic + Prebiotic) | Synergistic effect improving colonization of beneficial microbes (Figure 2) | Enhance immune tolerance and lower inflammatory markers of the patients | Support nutrient absorption and improve metabolic homeostasis. | [93] |

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) | Restores microbial diversity using donor stool | Re-establishes immune balance, restores Treg/Th17 ratio, improves response to immunotherapy in patients | Enhances metabolic function, reduces endotoxemia and systemic inflammation. | [3] |

| Dietary Interventions (Mediterranean diet, fermented foods) | Increase microbial richness and diversity | Promote immune tolerance, decrease pro-inflammatory pathways in hosts | Increase SCFA levels, improve cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes. | [94] |

| Microbiome-based Drugs (live biotherapeutics, engineered bacteria) | Target-specific pathways with microbial strains or engineered metabolites | Modulate tumor immunity, balance immune dysregulation in patients | Correct metabolic disorders by modulating bile acids and SCFAs. | [75] |

| Antibiotic Stewardship | Prevents broad-spectrum disruption of microbiota | Reduces dysbiosis-related immune dysfunction in patients | Preserves metabolic stability by maintaining microbial diversity | [95] |

7. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Other Health Conditions

7.1. Cardiovascular Diseases

- Key points:

- Gut microbes produce TMAO, strongly linked to atherosclerosis and stroke.

- Dysbiosis promotes gut leakiness and systemic inflammation.

- Microbiota influence cholesterol and bile acid metabolism, affecting lipid profiles.

- Reduced microbial diversity may worsen cardiovascular risk.

7.2. Neurological Disorders

- Key points:

- Gut microbes produce neurotransmitters (serotonin, GABA) critical for mood regulation in patients.

- Dysbiosis contributes to depression, anxiety, and neurodegeneration.

- Microbial changes may precede Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s symptoms.

- SCFAs affect patients’ brain signaling, inflammation, and IBS development.

7.3. Psoriasis and Skin Disorders

- Key points:

- Gut dysbiosis is linked to psoriasis, acne, dermatitis, and rosacea.

- Loss of SCFA-producing bacteria weakens Treg function and fuels inflammation.

- Low-fiber diets reduce SCFAs, worsening skin inflammation.

- Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory condition tied to gut microbiome imbalance.

7.4. Hormonal Regulation

- Key points:

- The estrobolome regulates estrogen reabsorption, influencing breast cancer and metabolic risk.

- Gut microbes shape bile acid metabolism, affecting lipid and glucose homeostasis.

- Secondary bile acids influence insulin sensitivity and fat storage.

- Dysbiosis contributes to PCOS, obesity, and diabetes.

8. Personalized and Translational Approaches

8.1. Recent Methods & Technologies

8.2. Microbiome Editing (CRISPR, Synthetic Biology)

- Key points:

- CRISPR and base editing enable precise genetic modification of gut bacteria.

- Engineered bacteriophages target antibiotic-resistant microbes.

- Synthetic biology allows microbes to produce therapeutic metabolites.

- In situ microbiome engineering manipulates bacteria within their natural habitat.

- Challenges: delivery, stability, safety, and long-term controllability.

8.3. Personalized Microbiome-Based Therapies

- Key points:

- Interventions are tailored to individual microbial profiles.

- Incorporates genetic, dietary, and lifestyle factors into therapy.

- Microbiome profiling guides personalized probiotics and microbiota-targeted drugs.

- Precision medicine integrates microbiome data to predict treatment response.

- Personalized approaches reduce variability in drug absorption and toxicity.

8.4. Ethical and Regulatory Challenges in Microbiome Research

- Key points:

- Classification of microbiome therapies (drug vs. supplement) affects regulation.

- Live-organism therapies (FMT, probiotics) require rigorous screening.

- Risks include pathogen transfer and variable safety outcomes.

- Ethical concerns involve informed consent and equitable access.

- Societal benefits must be weighed against risks in clinical application.

8.5. Long-Term Implications of Gut Microbiota Modulation

- Key points:

- Long-term effects of FMT and probiotics are not fully known.

- More longitudinal studies are required across diverse populations.

- Standardized sampling and clinical trial methods ensure reliable data.

- Microbiome changes during therapy may affect recurrence risk and side effects.

9. Limitations and Future Directions

9.1. Limitations of Microbiome Research

9.2. Future Directions

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hugon, P.; Lagier, J.C.; Colson, P.; Bittar, F.; Raoult, D. Repertoire of human gut microbes. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 106, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushchak, V.I. Symphony of Digestion: Coordinated Host–Microbiome Enzymatic Interplay in Gut Ecosystem. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Reddy, D.N. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 8787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgo, M.; Mostowy, S.; Ho, B.T. Emerging models to study competitive interactions within bacterial communities. Trends Microbiol. 2025, 33, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, N.A.; Ochman, H.; Hammer, T.J. Evolutionary and ecological consequences of gut microbial communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2019, 50, 451–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matijašić, M.; Meštrović, T.; Čipčić Paljetak, H.; Perić, M.; Barešić, A.; Verbanac, D. Gut microbiota beyond bacteria—Mycobiome, virome, archaeome, and eukaryotic parasites in IBD. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deering, K.E.; Devine, A.; O’Sullivan, T.A.; Lo, J.; Boyce, M.C.; Christophersen, C.T. Characterizing the composition of the pediatric gut microbiome: A systematic review. Nutrients 2019, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne, F.; Gotteland, M.; Gauthier, L.; Zazueta, A.; Pesoa, S.; Navarrete, P.; Balamurugan, R. The firmicutes/bacteroidetes ratio: A relevant marker of gut dysbiosis in obese patients? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Tremaroli, V.; Bäckhed, F. The gut microbiota. In The Prokaryotes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, X.; Li, L. Human gut microbiome: The second genome of human body. Protein Cell 2010, 1, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, M.; Higgins, P.D.; Middha, S.; Rioux, K.P. The human gut microbiome: Current knowledge, challenges, and future directions. Transl. Res. 2012, 160, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Di Ciaula, A.; Mahdi, L.; Jaber, N.; Di Palo, D.M.; Graziani, A.; Gyorgy, B.; Portincasa, P. Unraveling the role of the human gut microbiome in health and diseases. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olteanu, G.; Ciucă-Pană, M.A.; Busnatu, Ș.S.; Lupuliasa, D.; Neacșu, S.M.; Mititelu, M.; Musuc, A.M.; Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.-B.; Boroghină, S.C. Unraveling the microbiome–human body axis: A comprehensive examination of therapeutic strategies, interactions and implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaswal, A.S.; Mishra, S.; Elangovan, R. Prebiotic Oligosaccharide Production in Microbial Cells. In Microbial Nutraceuticals: Products and Processes; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 81–113. [Google Scholar]

- NCBI Taxonomy Database. National Center for Biotechnology Information. 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/taxonomy (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN). 2023. Available online: https://lpsn.dsmz.de/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Ahlawat, S.; Asha, N.; Sharma, K.K. Gut–organ axis: A microbial outreach and networking. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 72, 636–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portincasa, P.; Bonfrate, L.; Vacca, M.; De Angelis, M.; Farella, I.; Lanza, E.; Khalil, M.; Wang, D.Q.-H.; Sperandio, M.; Di Ciaula, A. Gut microbiota and short chain fatty acids: Implications in glucose homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.Z.; Ding, Y.D.; Xue, Q.M.; Cai, W.; Deng, H. Direct and indirect effects of pathogenic bacteria on the integrity of intestinal barrier. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2023, 16, 17562848231176427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mc Neil, V.; Lee, S.W. Advancing Cancer Treatment: A Review of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Combination Strategies. Cancers 2025, 17, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Sun, H. Advancements in understanding the role of intestinal dysbacteriosis mediated mucosal immunity in IgA nephropathy. BMC Nephrol. 2024, 25, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiyan, P.; Bhaskaran, N.; Zou, M.; Schneider, E.; Jayaraman, S.; Huehn, J. Microbiome dependent regulation of Tregs and Th17 cells in mucosa. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, L.; Gonzalez-Paramás, A.M.; Heleno, S.A.; Calhelha, R.C. Gut microbiota as an endocrine organ: Unveiling its role in human physiology and health. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslowski, K.M. Metabolism at the centre of the host–microbe relationship. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2019, 197, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L.M. Gut bacteria and neurotransmitters. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.Y.; Groer, M.; Dutra, S.V.O.; Sarkar, A.; McSkimming, D.I. Gut microbiota and immune system interactions. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, K.; Yan, L.; Wang, P.; Zhao, F.; Hu, S. The role of toll-like receptors in immune tolerance induced by Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2023, 28, e13020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero-Flores, G.; Pickard, J.M.; Núñez, G. Microbiota-mediated colonization resistance: Mechanisms and regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.E.; Fansler, R.T.; Zhu, W. Commensal resilience: Ancient ecological lessons for the modern microbiota. Infect. Immun. 2025, 93, e00502-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, M.; Alvarez, A.S.; de Vos, W.M. The gut microbiota in the first decade of life. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Pai, L.; Patil, S. Unveiling the dynamics of gut microbial interactions: A review of dietary impact and precision nutrition in gastrointestinal health. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1395664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, B.O.; Bäckhed, F. Signals from the gut microbiota to distant organs in physiology and disease. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giau, V.V.; Wu, S.Y.; Jamerlan, A.; An, S.S.A.; Kim, S.; Hulme, J. Gut microbiota and their neuroinflammatory implications in Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpellini, E.; Fagoonee, S.; Rinninella, E.; Rasetti, C.; Aquila, I.; Larussa, T.; Ricci, P.; Luzza, F.; Abenavoli, L. Gut microbiota and liver interaction through immune system cross-talk: A comprehensive review at the time of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Lau, H.C.; Zhang, X.; Yu, J. Bile acids, gut microbiota, and therapeutic insights in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol. Med. 2024, 21, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Turti, S.; Marza, S.M. Unraveling the Gut–Skin Axis: The Role of Microbiota in Skin Health and Disease. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.M.; Nassar, N.; Chang, H.; Khan, S.; Cheng, M.; Wang, Z.; Xiang, X. The microbiota: A key regulator of health, productivity, and reproductive success in mammals. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1480811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, J.C.; Ursell, L.K.; Parfrey, L.W.; Knight, R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: An integrative view. Cell 2012, 148, 1258–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidi, S.; Ali, K.; Khan, A.U. It’s all relative: Analyzing microbiome compositions, its significance, pathogenesis and microbiota derived biofilms: Challenges and opportunities for disease intervention. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, J.A.; Azad, M.B.; Bäckhed, F.; Blaser, M.J.; Byndloss, M.; Chiu, C.Y.; Chu, H.; Dugas, L.R.; Elinav, E.; Gibbons, S.M.; et al. Clinical translation of microbiome research. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1099–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, W.M.; Hill, E.S.; Fei, N.; Yee, A.L.; Garcia, M.S.; Cralle, L.E.; Gilbert, J.A. The human microbiome in health and disease. In Genomic Applications in Pathology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 607–618. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, J.; Redondo-Blanco, S.; Gutiérrez-del-Río, I.; Miguélez, E.M.; Villar, C.J.; Lombo, F. Colon microbiota fermentation of dietary prebiotics towards short-chain fatty acids and their roles as anti-inflammatory and antitumour agents: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 25, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zhu, J.; Xu, H. Strategies of Helicobacter pylori in evading host innate and adaptive immunity: Insights and prospects for therapeutic targeting. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1342913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baindara, P.; Mandal, S.M. Gut-antimicrobial peptides: Synergistic co-evolution with antibiotics to combat multi-antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, A.; Maiti, T.K.; Mahajan, D.; Das, B. Human gut microbiota and drug metabolism. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, R.; Singh, N.A.; Ahmed, N.; Choudhury, P.K. Bifidobacteria in antibiotic-associated dysbiosis: Restoring balance in the gut microbiome. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 41, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Bu, X.; Chen, D.; Wu, X.; Wu, H.; Caiyin, Q.; Qiao, J. Molecules-mediated bidirectional interactions between microbes and human cells. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Cao, Z.M.; Zhang, L.L.; Li, J.M.; Lv, W.L. The role of gut microbiota in some liver diseases: From an immunological perspective. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 923599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekara, A.; Somaratne, G. Functional food and nutraceuticals for the prevention of gastrointestinal disorders. In Industrial Application of Functional Foods, Ingredients and Nutraceuticals; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 501–534. [Google Scholar]

- Tiruvayipati, S.; Hameed, D.S.; Ahmed, N. Play the plug: How bacteria modify recognition by host receptors? Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 960326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonetti, F.R.; Eguileor, A.; Llorente, C. Goblet cells: Guardians of gut immunity and their role in gastrointestinal diseases. Egastroenterology 2024, 2, e100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brescia, C.; Audia, S.; Pugliano, A.; Scaglione, F.; Iuliano, R.; Trapasso, F.; Perrotti, N.; Chiarella, E.; Amato, R. Metabolic drives affecting Th17/Treg gene expression changes and differentiation: Impact on immune-microenvironment regulation. Apmis 2024, 132, 1026–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastida, G.; Mínguez, A.; Nos, P.; Moret-Tatay, I. Immunoepigenetic regulation of inflammatory bowel disease: Current insights into novel epigenetic modulations of the systemic immune response. Genes 2023, 14, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F. Gut microbiota, intestinal permeability, and systemic inflammation: A narrative review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 19, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Cotoner, C.; Abril-Gil, M.; Albert-Bayo, M.; Mall, J.P.G.; Expósito, E.; Gonzalez-Castro, A.M.; Lobo, B.; Santos, J. The role of purported mucoprotectants in dealing with irritable bowel syndrome, functional diarrhea, and other chronic diarrheal disorders in adults. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 2054–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gallausiaux, C.; Marinelli, L.; Blottière, H.M.; Larraufie, P.; Lapaque, N. SCFA: Mechanisms and functional importance in the gut. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 80, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Lou, X. Interplay Between Bile Acids, Gut Microbiota, and the Tumor Immune Microenvironment: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1638352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marafini, I.; Monteleone, I.; Laudisi, F.; Monteleone, G. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor signalling in the control of gut inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarracchini, C.; Lordan, C.; Milani, C.; Moreira, L.P.; Alabedallat, Q.M.; de Moreno de LeBlanc, A.; Turroni, F.; Lugli, G.A.; Mancabelli, L.; Longhi, G.; et al. Vitamin biosynthesis in the gut: Interplay between mammalian host and its resident microbiota. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2025, 89, e00184-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantri, A.; Klümpen, L.; Seel, W.; Krawitz, P.; Stehle, P.; Weber, B.; Koban, L.; Plassmann, H.; Simon, M.C. Beneficial effects of Synbiotics on the gut microbiome in individuals with low Fiber intake: Secondary analysis of a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Cui, J.; Jiang, S.; Zheng, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Q. Early life gut microbiota: Consequences for health and opportunities for prevention. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 5793–5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Schwartz, B. Interactions between dietary antioxidants, dietary Fiber and the gut microbiome: Their putative role in inflammation and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddison Rees, N. Investigating the Potential Senomorphic Properties of SCFA Butyrate on Aged T Cells. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, I.; Gibson, G.; Heinken, A.; Scott, K.; Swann, J.; Thiele, I.; Tuohy, K. Gut microbiota functions: Metabolism of nutrients and other food components. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, Q. Gut microbiota influences the efficiency of immune checkpoint inhibitors by modulating the immune system. Oncol. Lett. 2024, 27, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.; Ray Chaudhuri, S. The opportunistic nature of gut commensal microbiota. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 49, 739–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, R.; Takeda, K. The role of the mucosal barrier system in maintaining gut symbiosis to prevent intestinal inflammation. In Seminars in Immunopathology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; Volume 47, p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Aburto, M.R.; Cryan, J.F. Gastrointestinal and brain barriers: Unlocking gates of communication across the microbiota–gut–brain axis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 21, 222–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Yu, Y.; Tan, D.; Huang, X.; Huang, J.; Lin, C.; Yu, R. Microbiota and enteric nervous system crosstalk in diabetic gastroenteropathy: Bridging mechanistic insights to microbiome-based therapies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1603442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezfouli, M.A.; Rashidi, S.K.; Yazdanfar, N.; Khalili, H.; Goudarzi, M.; Saadi, A.; Kiani Deh Kiani, A. The emerging roles of neuroactive components produced by gut microbiota. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, L.; Di Benedetto, S. Neuroimmune crosstalk in chronic neuroinflammation: Microglial interactions and immune modulation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1575022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustrimovic, N.; Balkhi, S.; Bilato, G.; Mortara, L. Gut microbiota and immune system dynamics in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwer, E.K.; Ajagbe, M.; Sherif, M.; Musaibah, A.S.; Mahmoud, S.; ElBanbi, A.; Abdelnaser, A. Gut microbiota secondary metabolites: Key roles in GI tract cancers and infectious diseases. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafe, A.N.; Büsselberg, D. The Effect of Microbiome-Derived Metabolites in Inflammation-Related Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marroncini, G.; Naldi, L.; Martinelli, S.; Amedei, A. Gut–liver–pancreas axis crosstalk in health and disease: From the role of microbial metabolites to innovative microbiota manipulating strategies. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, S.A.; Patel, V.P.; Bhosle, K.P.; Nagare, S.D.; Thombare, K.C. The tumor microenvironment: Shaping cancer progression and treatment response. J. Chemother. 2025, 37, 15–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, A.; Andoh, A. The role of inflammation in cancer: Mechanisms of tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis. Cells 2025, 14, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garabatos, N.; Angelats, E.; Santamaria, P. Mechanistic and therapeutic advances in immune-mediated gastrointestinal disorders. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 165, 1133–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatelli, P.; Nuccio, F.; Piattelli, A.; Curia, M.C. The role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in oral and colorectal carcinogenesis. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.T. Dysfunction of the microbiota-gut-brain axis in neurodegenerative disease: The promise of therapeutic modulation with prebiotics, medicinal herbs, probiotics, and synbiotics. J. Evid.-Based Integr. Med. 2020, 25, 2515690X20957225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.M.; Tarfeen, N.; Mohamed, H.; Song, Y. Fermented foods: Their health-promoting components and potential effects on gut microbiota. Fermentation 2023, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, W.; Li, Q.; Yu, J. Gut microbiota modulation: A novel strategy for prevention and treatment of colorectal cancer. Oncogene 2020, 39, 4925–4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amen, R.A.; Hassan, Y.M.; Essmat, R.A.; Ahmed, R.H.; Azab, M.M.; Shehata, N.R.; Elgazzar, M.M.; El-Sayed, W.M. Harnessing the Microbiome: CRISPR-Based Gene Editing and Antimicrobial Peptides in Combating Antibiotic Resistance and Cancer. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 1938–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaqub, M.O.; Jain, A.; Joseph, C.E.; Edison, L.K. Microbiome-driven therapeutics: From gut health to precision medicine. Gastrointest. Disord. 2025, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.C.; Shanahan, E.R.; Scolyer, R.A.; Long, G.V. Towards modulating the gut microbiota to enhance the efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 697–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Xiong, M.; Jiang, A.; Huang, L.; Wong, H.Z.; Feng, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Chi, H.; et al. The microbiome in cancer. iMeta 2025, 4, e70070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciernikova, S.; Sevcikova, A.; Novisedlakova, M.; Mego, M. Insights into the Relationship Between the Gut Microbiome and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Solid Tumors. Cancers 2024, 16, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhao, P.; Gao, Q.; Yuan, L. The role of intestinal flora on tumorigenesis, progression, and the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in colorectal cancer. Cancer Biol. Med. 2024, 21, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Peng, G.; Song, W.; Zhou, X.; Huang, X.; Cao, X. Gut microbiota as a prognostic biomarker for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with anti-PD-1 therapy. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1366131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.; Yang, M.; Chen, M. Metabolic interactions: How gut microbial metabolites influence colorectal cancer. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1611698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyoti; Dey, P. Mechanisms and implications of the gut microbial modulation of intestinal metabolic processes. npj Metab. Health Dis. 2025, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahini, A.; Shahini, A. Role of interleukin-6-mediated inflammation in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease: Focus on the available therapeutic approaches and gut microbiome. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 17, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Ji, G.; Zhang, L. Immunomodulatory effects of inulin and its intestinal metabolites. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1224092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, K.M.; Shekhar, A.C. Lipopolysaccharide, arbiter of the gut–liver axis, modulates hepatic cell pathophysiology in alcoholism. Anat. Rec. 2025, 308, 975–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Habsi, N.; Al-Khalili, M.; Haque, S.A.; Elias, M.; Olqi, N.A.; Al Uraimi, T. Health benefits of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, and postbiotics. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafe, A.N.; Büsselberg, D. Microbiome integrity enhances the efficacy and safety of anticancer drug. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheemala, S.C.; Syed, S.; Bibi, R.; Suhail, M.B.; Dhakecha, M.D.; Subhan, M.; Mahmood, M.S.; Shabbir, A.; Islam, H.; Islam, R. Unraveling the gut microbiota: Key insights into its role in gastrointestinal and cardiovascular health. J. Adv. Med. Med. Res. 2024, 36, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X.; Wei, X.; Wang, J.; Yao, X.; Zhang, M.; Sun, D.; Liang, J.; Chi, L.; Cheng, Y. Impacts of intestinal microbiota metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide on cardiovascular disease: A bibliometric analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1491731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttiah, B.; Hanafiah, A. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Diseases: Unraveling the Role of Dysbiosis and Microbial Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, A.; Lev-Ari, S. Targeting the Gut Microbiome to Improve Immunotherapy Outcomes: A Review. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2024, 23, 15347354241269870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, I.; Juneja, K.; Nimmakayala, T.; Bansal, L.; Pulekar, S.; Duggineni, D.; Ghori, H.K.; Modi, N.; Younas, S. Gut Microbiota and Mental Health: A Comprehensive Review of Gut-Brain Interactions in Mood Disorders. Cureus 2025, 17, e81447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagodic, A.; Krsek, A.; Schleicher, L.M.S.; Baticic, L. Microbiome Dysbiosis as a Driver of Neurodegeneration: Insights into Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Gastrointest. Disord. 2025, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Funasaka, Y.; Saeki, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Kanda, N. Dietary fiber inulin improves murine imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahi, N.; Rafiee, M.; Hosseini, S.S.; Sereshki, N.; Anani Sarab, G.; Erfanian, N. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Their Role in Modulating Autoimmune Responses in Psoriasis: Insights from Recent Microbiota Research. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 78, ovaf091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larnder, A.H.; Manges, A.R.; Murphy, R.A. The estrobolome: Estrogen-metabolizing pathways of the gut microbiome and their relation to breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 157, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.; Devi Rajeswari, V.; Ganesh, V.; Das, S.; Dhanasekaran, S.; Usha Rani, G.; Ramanathan, G. Gut microbiome and polycystic ovary syndrome: Interplay of associated microbial-metabolite pathways and therapeutic strategies. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 31, 1508–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, S.; Qi, L.; Zalloua, P. From omics to AI—Mapping the pathogenic pathways in type 2 diabetes. FEBS Lett. 2025, 599, 3244–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northen, T.R.; Kleiner, M.; Torres, M.; Kovács, Á.T.; Nicolaisen, M.H.; Krzyżanowska, D.M.; Sharma, S.; Lund, G.; Jelsbak, L.; Baars, O.; et al. Community standards and future opportunities for synthetic communities in plant–microbiota research. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 2774–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, V.; Singh, S.; Verma, S.; Verma, S.; Rizvi, A.A.; Abbas, M. Targeting the microbiome to improve human health with the approach of personalized medicine: Latest aspects and current updates. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 63, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayesiga, I.; Iqbal, S.; Kyejjusa, Y.; Okoboi, J.; Omara, T.; Adelina, T.; Deogratias, D.; Anyole, A.A.; Kagimu, B.B.; Odongo, D.; et al. Key regulatory aspects of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in the management of metabolic disorders. In Synbiotics in Metabolic Disorders; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 214–244. [Google Scholar]

- Ejtahed, H.S.; Parsa, M.; Larijani, B. Ethical challenges in conducting and the clinical application of human microbiome research. J. Med. Ethics Hist. Med. 2023, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Cordaillat-Simmons, M.; Badalato, N.; Berger, B.; Breton, H.; de Lahondès, R.; Deschasaux-Tanguy, M.; Desvignes, C.; D’humières, C.; Kampshoff, S.; et al. Microbiome testing in Europe: Navigating analytical, ethical and regulatory challenges. Microbiome 2024, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongre, D.S.; Saha, U.B.; Saroj, S.D. Exploring the role of gut microbiota in antibiotic resistance and prevention. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2478317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyap, P.C.; Chia, N.; Nelson, H.; Segal, E.; Elinav, E. Microbiome at the frontier of personalized medicine. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 92, pp. 1855–1864. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, B.C.; Zuppi, M.; Derraik, J.G.; Albert, B.B.; Tweedie-Cullen, R.Y.; Leong, K.S.; Beck, K.L.; Vatanen, T.; O’Sullivan, J.M.; Cutfield, W.S. Long-term health outcomes in adolescents with obesity treated with faecal microbiota transplantation: 4-year follow-up. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohammad, I.; Ansari, M.R.; Khan, M.S.; Bari, M.N.; Kamal, M.A.; Poyil, M.M. Beyond Digestion: The Gut Microbiota as an Immune–Metabolic Interface in Disease Modulation. Gastrointest. Disord. 2025, 7, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/gidisord7040077

Mohammad I, Ansari MR, Khan MS, Bari MN, Kamal MA, Poyil MM. Beyond Digestion: The Gut Microbiota as an Immune–Metabolic Interface in Disease Modulation. Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2025; 7(4):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/gidisord7040077

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohammad, Imran, Md. Rizwan Ansari, Mohammed Sarosh Khan, Md. Nadeem Bari, Mohammad Azhar Kamal, and Muhammad Musthafa Poyil. 2025. "Beyond Digestion: The Gut Microbiota as an Immune–Metabolic Interface in Disease Modulation" Gastrointestinal Disorders 7, no. 4: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/gidisord7040077

APA StyleMohammad, I., Ansari, M. R., Khan, M. S., Bari, M. N., Kamal, M. A., & Poyil, M. M. (2025). Beyond Digestion: The Gut Microbiota as an Immune–Metabolic Interface in Disease Modulation. Gastrointestinal Disorders, 7(4), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/gidisord7040077