1. Introduction

Johann Friedrich Meckel (1781–1833) first described in 1809 a remnant of the prenatal vitelline duct that typically fails to close between the fifth and seventh week of gestation, elucidating its connection to the primitive small bowel and yolk sac in chicken embryos [

1,

2]. This outpouching of the ileum, named Meckel’s diverticulum (MD), is a common intestinal anomaly occurring in 1–4% of the population [

3]. Its appearance resembles a digital pocket, ranging in length from 3 to 6 cm, usually arising from the antimesenteric border of the ileum 20 to 60 cm before the ileocecal valve [

4], with bleeding as the most common complication due to the ectopic gastric or pancreatic mucosa lining its inner surface [

5,

6]. The occurrence of an MD on the mesenteric border (MMD), on the contrary, is a rare occurrence, difficult to diagnose, and presenting a higher risk of complications, because, being embedded in the mesentery, in the case of advanced inflammation, it can erode surrounding tissues and rupture into the mesenteric vessels [

7]. Moreover, its unexpected location can, at imaging, mimic an enteric duplication cyst, hypertrophic ileal tuberculosis, gut lymphoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), lymphoma, or other rare intestinal neoplasms, posing a difficult diagnostic dilemma [

8].

Opposite to its normal presentation on the antimesenteric border, often asymptomatic, MMD usually presents with a wide array of possible associated symptoms, such as right lower quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting, and can be easily confused with other acute abdominal conditions: as stated before, rectal bleeding is an important and typical differential diagnostic feature of MMD, prompting for a diagnostic workup. This can include an abdominal ultrasound (US) to rule out conditions like appendicitis and CT scans to assess complications like obstruction [

9]. The gold standard for detecting ectopic gastric mucosa is considered scintigraphy with Technetium-99m Pertechnetate, offering high specificity but moderate sensitivity [

10].

When imaging is inconclusive, laparoscopy may be used for both diagnosis and treatment, as in our experience on three children affected by MMD and treated via a laparo-assisted approach. Our patients will be presented together with a systematic literature review to enhance our understanding of this rare anomaly.

2. Cases Presentation

2.1. Case 1

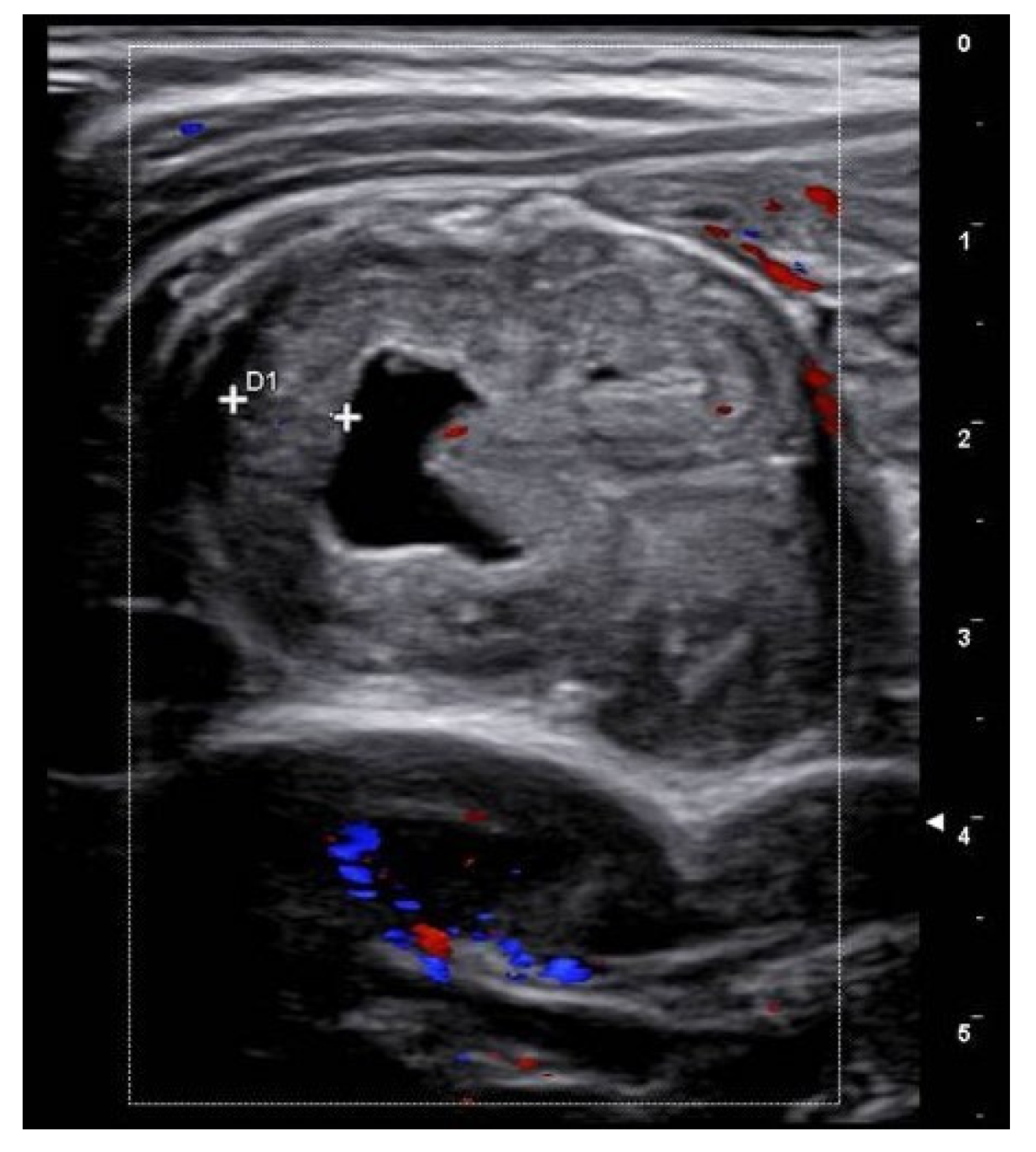

A 6-year-old boy with no prior medical history presented to a peripheral hospital’s emergency department with periumbilical pain and rectal bleeding. His vital signs were as follows: a temperature of 36.6 °C, a pulse rate of 107/min, a blood pressure of 116/75 mmHg, and a respiratory rate of 28/min. Laboratory tests indicated an Hb of 6.9 g/dL (normal values for age > 11.5 g/d), while the serum leukocyte count and C-reactive protein (CRP) were within normal ranges. A blood transfusion was administered, stabilizing his condition temporarily. Abdominal US showed no pathological findings. Subsequent upper and lower endoscopic evaluation revealed residual blood in the colon and ileum, but no active bleeding sites. The patient was then transferred to our center where repeated abdominal US revealed a cystic lesion in the mesogastric region, approximately 2 cm in length and communicating with the small bowel lumen (

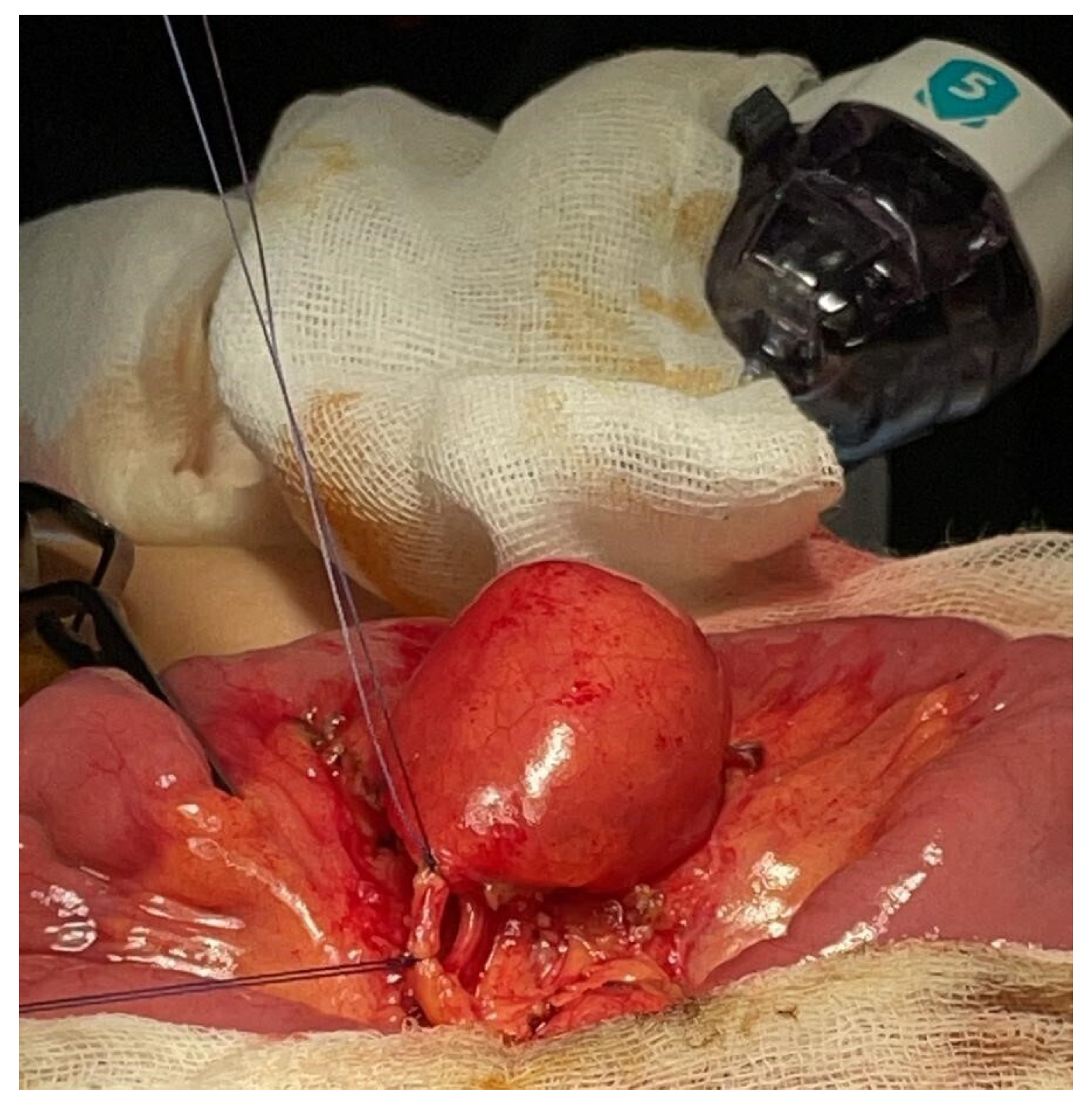

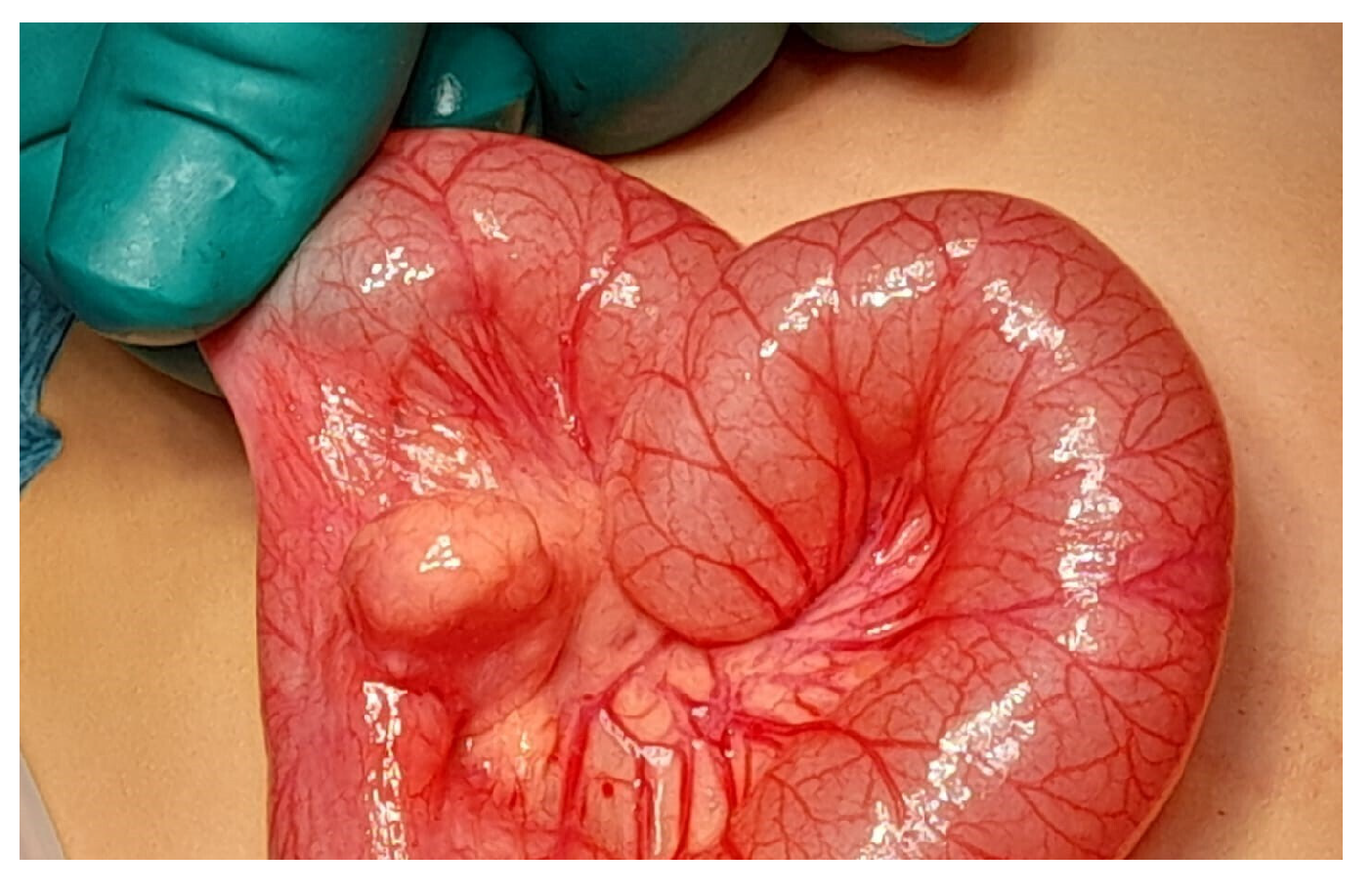

Figure 1). A bleeding MD was then suspected, and the patient underwent laparoscopic exploration. The entire small bowel was examined, and a mesenteric mass similar to an intestinal duplication was found, approximately 60 cm from the ileocecal valve. The lesion was exteriorized through the umbilical incision (

Figure 2). Dissection confirmed that the mass was connected to the mesenteric side of the small bowel, with a short artery arising from a mesenteric branch, confirming the diagnosis of MMD (

Figure 3). A 5 cm long segment of the small bowel including the mass was resected, and a primary end-to-end anastomosis was performed. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged after five days with no need for further blood transfusions. Histopathological evaluation confirmed the diagnosis of MMD with ectopic gastric mucosa. Inizio modulo

2.2. Case 2

A 15-year-old boy presented to our emergency department after three episodes of melena starting from the previous day, with no associated symptoms. Vital signs were stable, and laboratory tests showed an Hb of 14.7 g/dL (normal values for age ≥ 12 g/dL), with a normal leukocyte count and CRP. Digital rectal examination yielded inconclusive results. The presence of repeated episodes of melena raised the suspicion of a gastric lesion, thus prompting for a gastroscopy, which did not reveal ulcerative lesions. A laparoscopic exploration was then performed, and a mesenteric mass was identified approximately 45 cm from the ileocecal valve on the mesenteric side of the ileum.

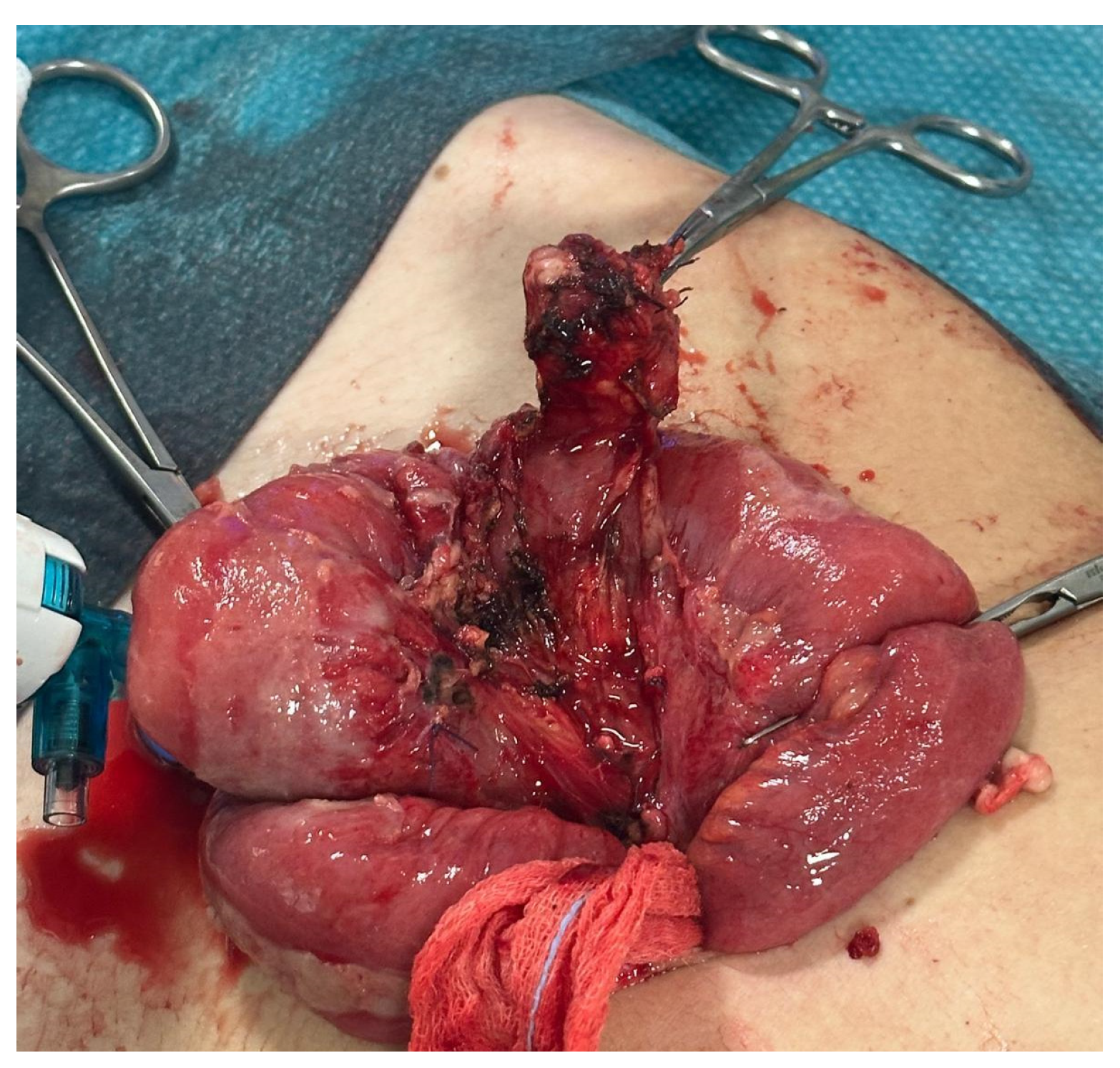

The mass and a short ileal segment were exteriorized through the umbilical incision (

Figure 4). Dissection confirmed that the mass was connected to the ileum; a 4 cm long segment of the small bowel including the mass was resected, followed by an end-to-end anastomosis.

The postoperative course was complicated by symptoms suggestive of obstruction, leading to a new exploratory laparoscopy with adhesiolysis on the 7th postoperative day. The second postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was discharged 6 days after the reintervention. Histopathological evaluation confirmed the diagnosis of MMD with heterotopic gastric mucosa.

2.3. Case 3

A 2-year-old girl presented to the emergency department with melena, without abdominal pain. Her vital signs were as follows: a temperature of 36.3 °C, a heart rate of 138/min, and a blood pressure of 94/58 mmHg. Blood tests showed mild neutrophilic leucocytosis (WBC 12.64 U/µL, neutrophilis 6.8 U/µL), with no increase in CRP. Abdominal US was negative, but melena episodes persisted, and the Hb dropped from 10.4 to 7.2 g/dL (normal values for age > 11 g/dL), requiring blood transfusion.

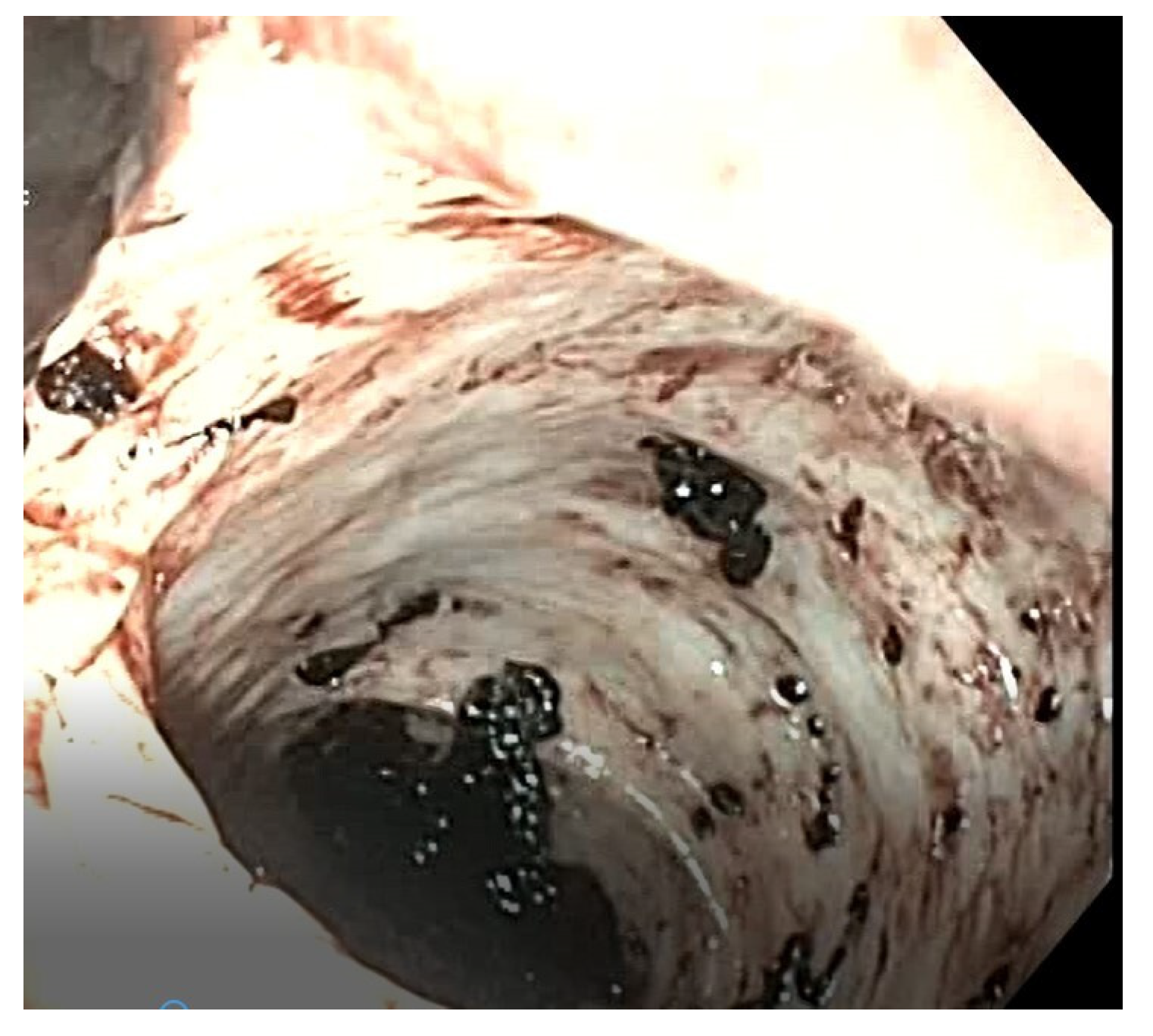

An upper and lower endoscopy revealed residual blood without active bleeding, leading to a suspicion of a bleeding MD (

Figure 5). Laparoscopic exploration confirmed the suspected diagnosis, revealing a diverticulum located on the mesenteric border approximately 70 cm from the ileocecal valve. The ileal segment was exteriorized through the umbilical access (

Figure 6), and a segmental resection including the diverticulum was performed, followed by an end-to-end ileo–ileal anastomosis. Postoperative recovery was uneventful, and the patient was discharged after 10 days. Histological examination confirmed the diagnosis of MMD.

Demographic data and clinical details of our three cases are resumed in

Table 1.

3. Systematic Literature Review

A systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria [

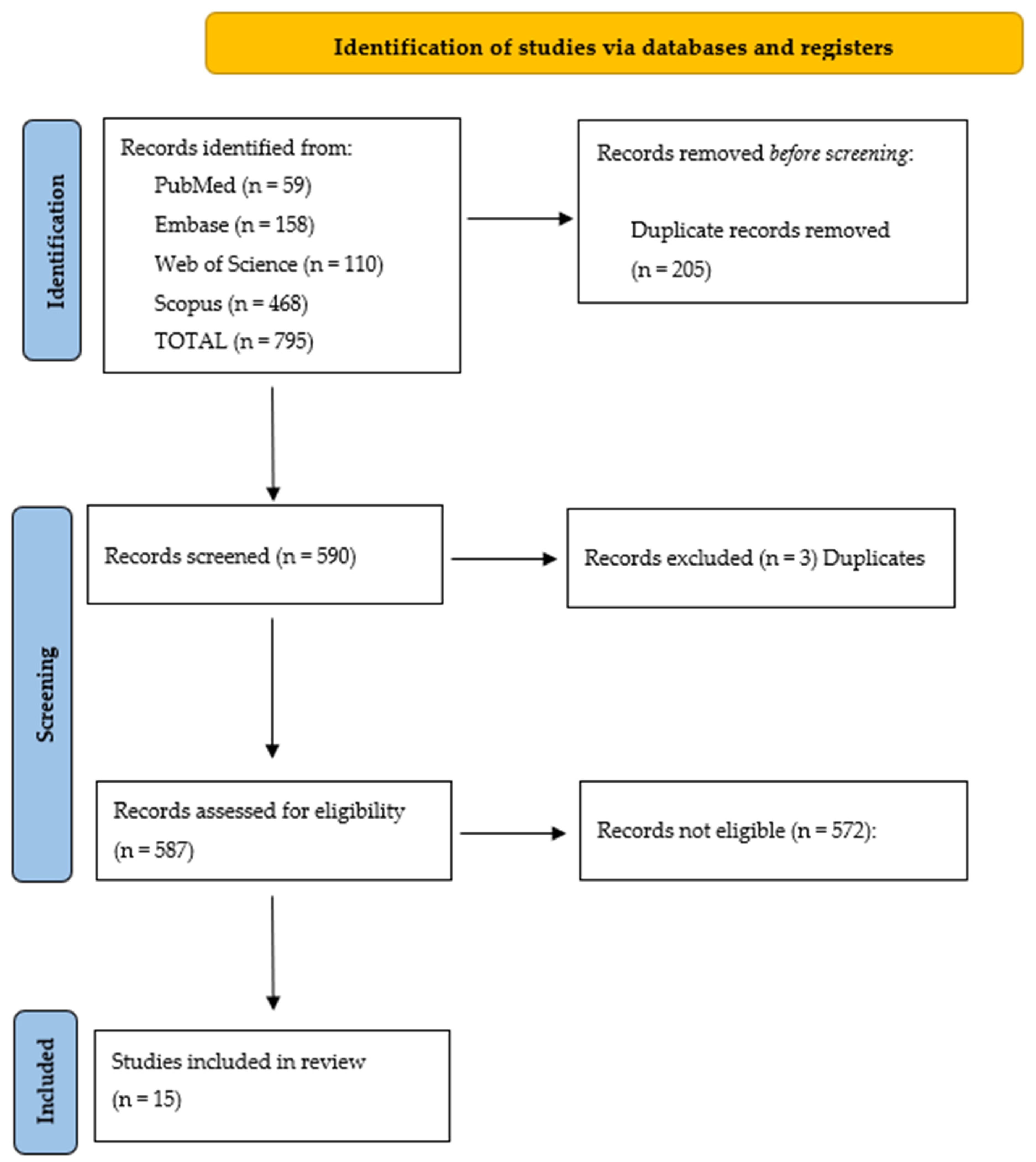

11]. Articles were searched for in PubMed, EMBASE, SCOPUS, and Web of Science with the following research query: “(Meckel) AND (diverticulum) AND (mesenteric)”.

The literature search yielded 795 citations. References management (February 2025) allowed us to identify 205 overlapping papers, thus reducing the articles to 590. These were then screened independently by two authors (VV and GF) to verify inclusion criteria, namely cases of MMD in patients < 18 years of age, articles written in English, and particularly excluding those where the term “mesenteric” was aspecifically quoted, i.e., not referring to the anatomic position of the MD on the mesenteric border.

It was thus possible to verify that only 15 papers were matching the inclusion criteria [

2,

7,

8,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The relevant PRISMA flow chart is detailed in

Figure 7.

A total of 20 children were extracted from the 15 selected papers and analyzed, considering (whenever available) age, symptoms, signs, diagnostic workup, treatment, histopathological findings, complications, outcome, and length of hospital stay. Relevant data are summarized in

Table 2.

Mean age of presentation (available in 15 out of 20 cases) was 5.9 years (range of 3 months–15 years). Most of the represented presenting symptoms, reported in 15 out of 20 cases, were abdominal pain (53%) and intestinal bleeding (47%); other symptoms included nausea or vomiting (33%), fever (20%), and umbilical discharge due to the patent omphalomesenteric duct (7%).

Preoperative workup was reported in fourteen out of twenty cases and included eleven abdominal US (80%), seven Technetium-99m scintigraphy (50%), and three CT scan (21%). Endoscopy was performed in only one patient (7%).

Surgical technique details are available for fifteen patients: twelve patients (80%) were operated on with an open approach, while three (20%) with a laparoscopic approach. In twelve patients, a segmental bowel resection followed by end-to-end anastomosis was performed (two of them laparoscopically), and in the remainder three cases, a simple diverticulectomy was performed, in one case by the laparoscopic approach; the other two cases were approached by laparotomy, and in one of these, MMD was found incidentally during appendectomy. In all cases, histopathological findings revealed an MMD, lined with gastric mucosa in fourteen out fifteen documented cases (93%); in three cases, a diverticulitis was ongoing, advanced up to a gangrenous stage in one, and a perforation in another. No intraoperative or postoperative complication was mentioned in the analyzed papers.

4. Discussion

Results of the systematic review, joined with our case series, allow us to highlight some relevant issues related to MMD, shortly discussed here.

4.1. Rarity

Since the first case of MMD described by Chaffin in 1941, we have been able to find in the literature only 19 other pediatric cases.

4.2. Etiology

The etiology of MMD remains unknown, though a couple of theories have been proposed:

- (a)

The persistence of the short vitelline artery which creates a mesodiverticular band from the mesentery to the tip of the diverticulum, thus diverting the diverticulum away from the antimesenteric border during the process of the elongation [

7,

21].

- (b)

The adherence of the vitelline duct to the ileal mesentery due to congenital or inflammatory adhesions [

24].

In our experience, the presence of a very short artery supplying the MMD lends support to the first theory.

4.3. Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

From our experience, and from the review of the literature, it appears that the clinical presentation of MMD is totally unspecific and presenting symptoms may be similar to other pediatric abdominal conditions. The most relevant differential diagnosis is with Enteric Duplication Cysts (EDCs) [

16]: actually, gastric and intestinal EDCs can present with nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention, abdominal pain, or palpable abdominal mass. A complicated EDC can present with intussusception, intestinal obstruction, inflammation, ulceration, and intestinal bleeding, with the very same symptoms of an MMD [

25].

4.4. Lack of a Codified Diagnostic Workup

Based on the collected data, it is evident that no standardized diagnostic protocol exists, leading to the use of various imaging techniques to identify MD. Moreover, in the case of MMD, the diagnosis may be particularly challenging since images closely resemble those of EDC, hypertrophic ileal tuberculosis, gut lymphoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, lymphoma, or other rare intestinal neoplasms [

8]. The key distinction between an MMD and an EDC lies in the communication between the lumen of the MD and the ileum; in contrast, EDCs typically share a wall with the ileum but do not communicate with its lumen. Additionally, MD has its own arterial supply [

16], whereas EDC share their blood supply with the ileum.

The Technetium-99m scan has been considered the standard diagnostic procedure to confirm the presence of an MD; however, from our analysis of the recent literature, it turns out that this procedure in children is less and less used, especially in cases of massive gastrointestinal bleeding or melena, given the relatively low sensitivity of the exam [

10] and the need—in younger patients—to perform the examination under general anesthesia, thus delaying a possibly urgent surgical intervention.

Consequently, there has been a growing tendency in recent years to rely on alternative diagnostic methods [

8]. General anesthesia is a crucial factor: scintigraphy alone serves as a diagnostic tool and not as a therapeutic one. Therefore, if the diagnosis is confirmed, the child would require a second anesthesia for surgical treatment. Based on our experience (shared only with another one in the literature [

21]), the use of endoscopy under anesthesia as the preferred approach for investigating gastrointestinal bleeding allows—if the examination turns out to be negative—the easy conversion of the procedure into an exploratory laparoscopy during the same anesthesia. Once the diagnosis of MMD is confirmed, the explorative laparoscopic approach can be immediately converted into a therapeutic procedure. Low invasiveness of laparoscopic procedures performed with pediatric instruments makes this approach a safe and practical option even for younger children.

4.5. Lack of Standardized Treatment Strategies

Based on the literature analysis and our surgical experience, it turns out that surgical intervention is the definitive treatment for MMD, even when it is asymptomatic and discovered incidentally [

21].

An open laparotomy is still described as the standard approach for MMD, with only two cases in the recent pediatric literature having been treated laparoscopically. Based on our experience in which all patients with MMD were treated with a minimally invasive approach, we can conclude that laparoscopy facilitates both diagnosis and treatment of the pathology while potentially reducing the need for extensive imaging investigations; hence, it should be considered beneficial in cases that are highly suspected for MD, also in its mesenteric variant.

The limitations of this study consist of its retrospective design and relatively small sample size, although justified by the rarity of the pathology described in the pediatric age group; moreover, the heterogeneity in patients’ clinical characteristics and surgical strategies adopted, as well as the significant amount of missing data in the first cases reported, present challenges for a thorough analysis and a generalization of results.

5. Conclusions

MMD is a rare variant of MD characterized by its mesenteric location and associated diagnostic challenges. Its rarity and aspecific symptoms often lead to diagnostic delays, further compounded by the lack of standardized protocols of diagnosis and treatment.

Hence, it is imperative to maintain a high level of clinical suspicion for this pathology, particularly in cases presenting with acute abdomen or unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding.

A minimally invasive approach to this rare anomaly is a valuable tool for both final diagnosis and treatment.

Prompt recognition and surgical intervention, when warranted, are essential to prevent complications and optimize outcomes. This report highlights the need for further research to standardize diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and M.R.; methodology, C.N.; software, V.V. and G.F.; validation, M.B., A.R. and G.B.P.; formal analysis, V.V. and G.F.; investigation, M.B., S.M. and A.R.; resources, M.R.; data curation, V.V., M.R. and G.F.; writing—original draft preparation, V.V.; writing—review and editing, G.B.P.; visualization, C.N.; supervision, M.B. and G.B.P.; project administration, M.B.; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our institution does not require Institutional Review Board approval for retrospective studies and literature reviews.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for publication of data have been signed from the parents of all our three patients.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yahchoucy, E.K.; Marano, A.F.; Étienne, J.F.; Fingerhut, A.L. Meckel’s diverticulum. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2001, 192, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaffin, L. Surgical emergencies during childhood caused by Meckel’s diverticulum. Ann. Surg. 1941, 113, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, J.; Kumar, V.; Shah, D.K. Meckel’s diverticulum: A systematic review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2006, 99, 501–505, Erratum in J. R. Soc. Med. 2007, 100, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, C.C.; Søreide, K. Systematic review of epidemiology, presentation, and management of Meckel’s diverticulum in the 21st century. Medicine 2018, 97, e12154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertozzi, M.; Melissa, B.; Radicioni, M.; Magrini, E.; Appignani, A. Symptomatic Meckel’s diverticulum in newborn: Two interesting additional cases and review of literature. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2013, 29, 1002–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seagram, C.G.; Louch, R.E.; Stephens, C.A.; Wentworth, P. Meckel’s diverticulum: A 10-year review of 218 cases. Can. J. Surg. 1968, 11, 369–373. [Google Scholar]

- Sarioglu-Buke, A.; Corduk, N.; Koltuksuz, U.; Karabul, M.; Savran, B.; Bagci, S. An uncommon variant of Meckel’s diverticulum. Can. J. Surg. 2008, 51, E46–E47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koetter, P.; Cochran, E.; Tsai, A.Y. Mesenteric Meckel’s diverticulum in a 17-month-old female. J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 2021, 69, 101835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.S.E.; Teo, H.E.L. The Meckel’s diverticulum and its complications—Pictorial review of imaging findings. Pediatr. Radiol. 2021, 51, S147. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, P.; Jiang, S. Tc-99m scan for pediatric bleeding Meckel diverticulum: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. (Rio J.) 2023, 99, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, X.N.; Nguyen, L.T.; Tran, N.N. Omphalomesenteric duct anomalies in children: A report of 46 cases. Ann. Chir. Infant. 1975, 16, 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzbart, E.; Zeitlin, M.; Feigenbaum, D.; Zaritzky, A.; Cohen, Z.; Mares, A.J. Rare spontaneous regression of patent omphalomesenteric duct after birth. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002, 86, F63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manukyan, M.N.; Kebudi, A.; Midi, A. Mesenteric Meckel’s diverticulum: A case report. Acta Chir. Belg. 2009, 109, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, I.; Khan, N.; Neqash, S.; Choudri, N.; Wani, K. Mesenteric Meckel’s diverticulum. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 24, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Panda, S.S.; Sharma, N.; Bajpai, M. Meckel’s diverticulum at uncommon mesenteric location. J. Indian Assoc. Pediatr. Surg. 2013, 18, 127–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, P.; Panda, S.; Das, R.; Mallick, S. Mesenteric location of Meckel’s diverticulum: Is it really uncommon? Saudi J. Health Sci. 2014, 3, 166–167. [Google Scholar]

- Yagnik, V.D.; Dawka, S. Mesenteric Meckel’s diverticulum: An intra-abdominal surprise. ANZ J. Surg. 2019, 89, 1516–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, A.; Dell’Oro, M.G. An uncommon location of a Meckel’s diverticulum mimicking small intestinal duplication cyst. Chirurgia 2020, 33, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagnik, V.D. Gangrenous mesenteric Meckel’s diverticulum: An uncommon cause of intestinal obstruction. ANZ J. Surg. 2021, 91, 1626–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhamisy, A.; Douba, Z.; Jawish, H.; Helaly, H.; Alkhalaf, Y.; Alhaj, A.; Morjan, M. Symptomatic mesenteric Meckel’s diverticulum in a toddler. J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 2021, 72, 101978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, D.; Reddy, P.K.; Sarangi, R.; Pradhan, A. Pediatric Meckel’s diverticulum: Experience from a tertiary center in Eastern India. Rom. J. Pediatr. 2023, 72, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagnik, V.D.; Garg, P.; Dawka, S.; Bhattacharya, K. Mesenteric Meckel’s diverticulitis with perforation: A rare finding on laparotomy. Indian J. Surg. 2023, 85, 444–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahindru, S.; Singh, S.; Sandhu, M.S.; Kumar, A. Meckel’s diverticulum in ectopic location: A rare presentation. Saudi Surg. J. 2017, 5, 82–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sangüesa Nebot, C.; Llorens Salvador, R.; Carazo Palacios, E.; Picó Aliaga, S.; Ibañez Pradas, V. Enteric duplication cysts in children: Varied presentations, varied imaging findings. Insights Imaging 2018, 9, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).