1. Introduction

Per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) is gaining growing recognition as one of the most successful natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) procedures for the minimally invasive treatment of achalasia and other spastic orders of the esophagus [

1,

2]. Gastric per-oral endoscopic myotomy (G-POEM) is a type of submucosal endoscopy derived from POEM that targets the pylorus muscle for the treatment of gastroparesis [

3]. E-POEM and G-POEM involve a longitudinal or transverse mucosal incision, followed by the entry of an endoscope in the submucosa, the creation of a submucosal tunnel towards the lower esophageal sphincter/pyloric ring, and the closure of the mucosotomy [

4,

5].

One of the most crucial steps in POEM is to obtain adequate mucosal closure to avoid major complications like the leakage of esophageal/gastric contents into the mediastinal space, leading to peritonitis [

6]. Endoscopic clipping is the most frequently used modality in the closure of mucosotomy; however, newer modalities available for mucosotomy closure are endoscopic sutures, over-the-scope clips (OTSC), endoloop-based techniques, fibrin glue, and covered stents in complex cases as a last resort [

6,

7].

There are a few studies comparing the effectiveness and outcomes of endoscopic clips and endoscopic sutures for the closure of mucosotomy in patients undergoing E-POEM and G-POEM; however, there is no meta-analysis assessing the effectiveness, outcomes, and cost-benefit of endoscopic clipping versus endoscopic suturing techniques. This meta-analysis aims to systematically evaluate the technical success rates and outcomes of endoscopic clipping compared to endoscopic suturing in mucosotomy closure during E-POEM and G-POEM, ultimately informing best practices and potentially optimizing patient care.

2. Results

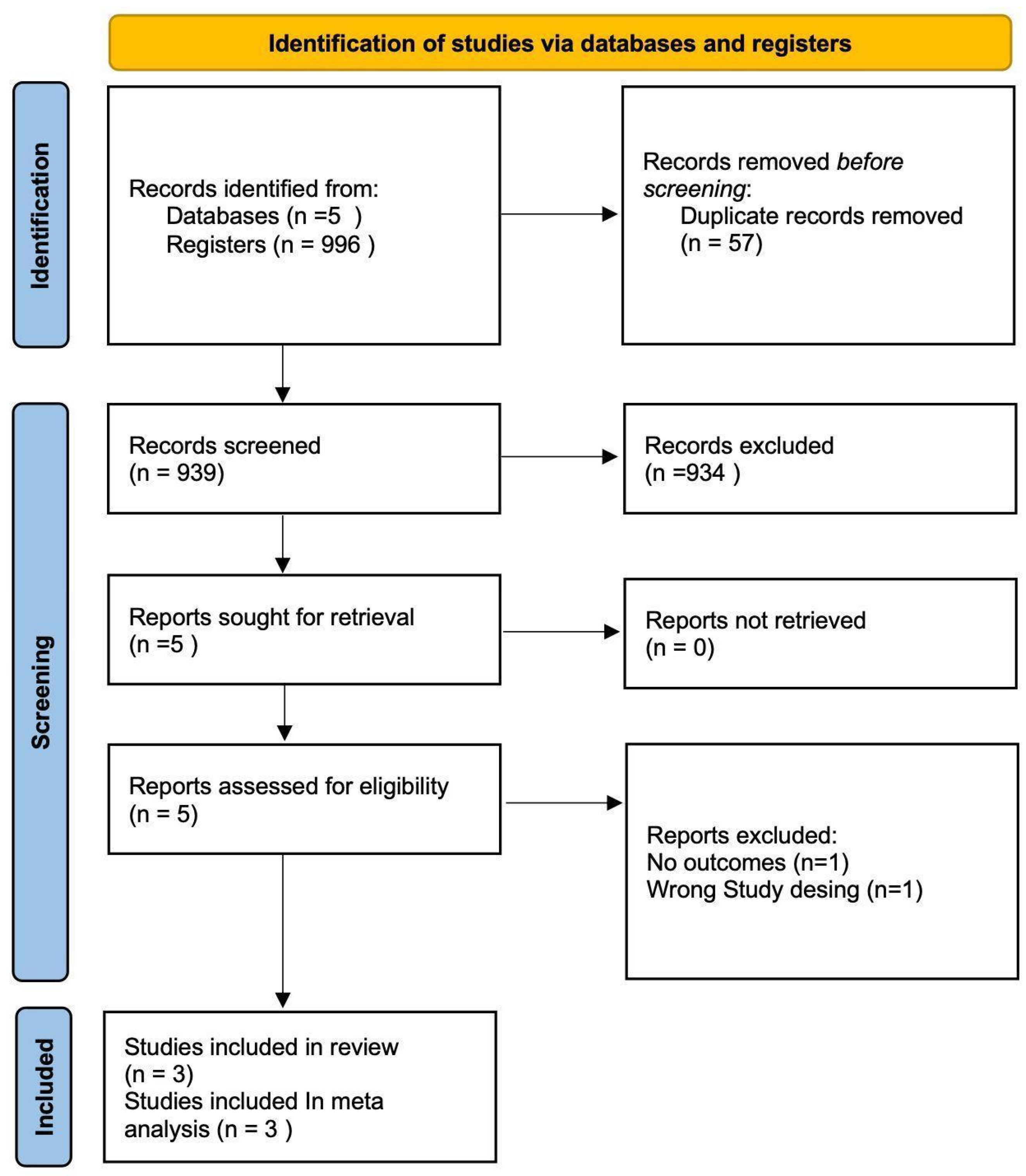

A total of 939 studies underwent title screening and abstract screening, out of which five studies were included for full-text screening, and a total of three studies were included in the final analysis, as shown in the PRISMA flowchart (

Figure 1). Our study included two studies published as full manuscripts and one study published in abstract form, with a total population of 91 individuals across all studies. Each study compared the technical success rates and outcomes of endoscopic clips and endoscopic suturing devices in the closure of mucosotomy after E-POEM or G-POEM. The other outcomes measured were the cost of the procedure, the time needed for closure, and the complications of the procedure. The age of the participants ranged from 51 to 70 years in the clipping group and from 44 to 72 years in the suture group. The patient demographics and the indication for E-POEM/G-POEM in the included studies are mentioned in

Table 1. The technical success rates and outcomes of the individual studies included in the analysis are described in

Table 2.

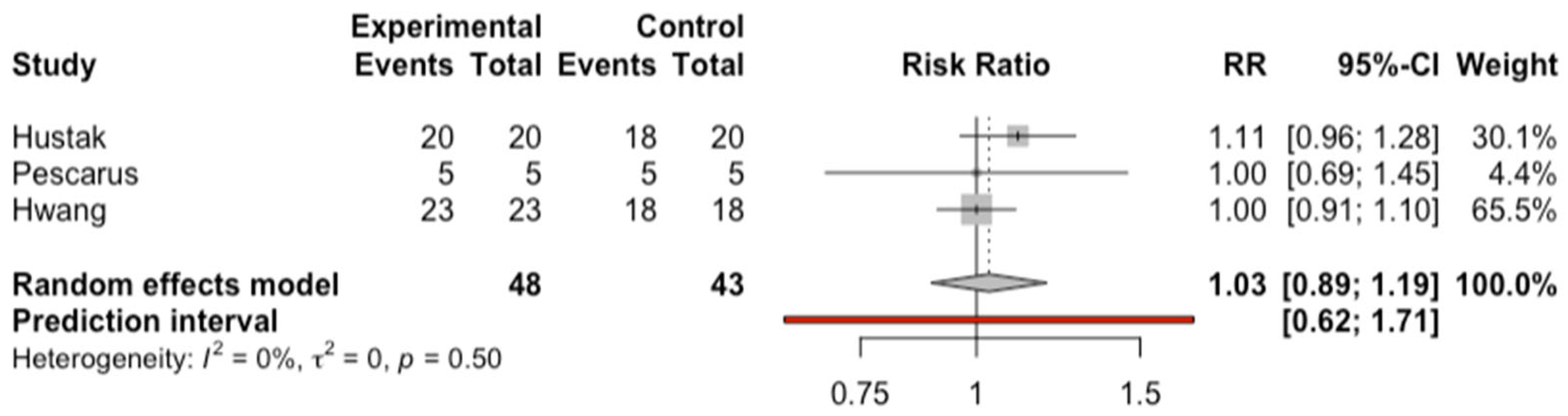

In the direct comparative analysis, technical success rates were compared based on the successful closure of the mucosotomy in the endoscopic clipping group and the suture group. The results indicated no statistical significance in the technical success rates of endoscopic clipping versus sutures (OR: 1.03; CI: 0.89 to 1.19;

p = 0.50), as depicted in

Figure 2, with a low heterogeneity measured with tau2 (0; CI: 0 to 0.12), I2 (0; CI:0 to 89.6%), and Q tests (1.4; df:2;

p = 0.49). Additionally, the leave-one-out analysis did not show that any study significantly modified the effect size or heterogeneity.

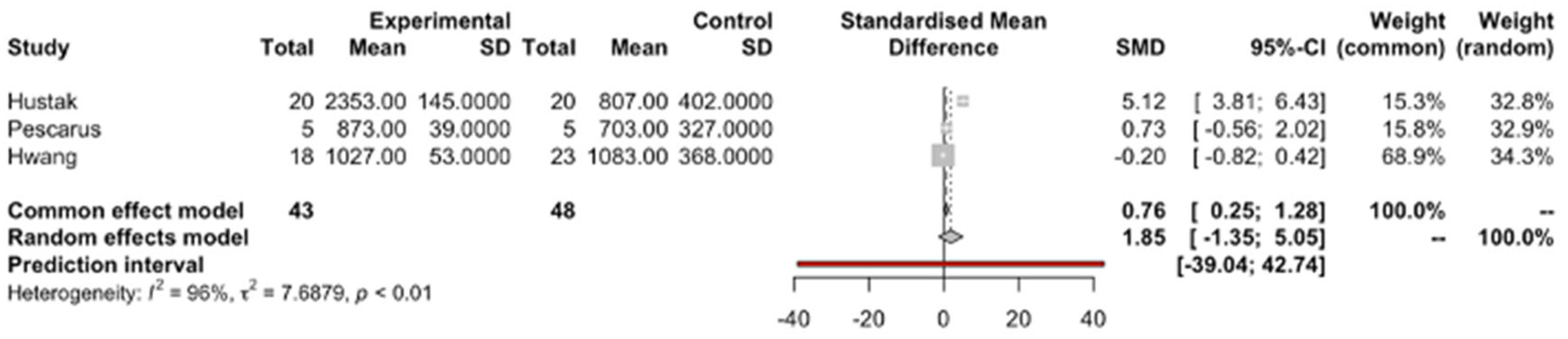

The costs of endoscopic sutures were not statistically significantly different from each other (SMD 1.85; CI −5.05 to 1.35;

p = 0.25), as depicted in

Figure 3, with a high heterogeneity evidenced by tau2 (768; CiO1.83 to >100), I2 (96%; CI: 91.8% to 98.2%), and Q tests (51.72; df:2,

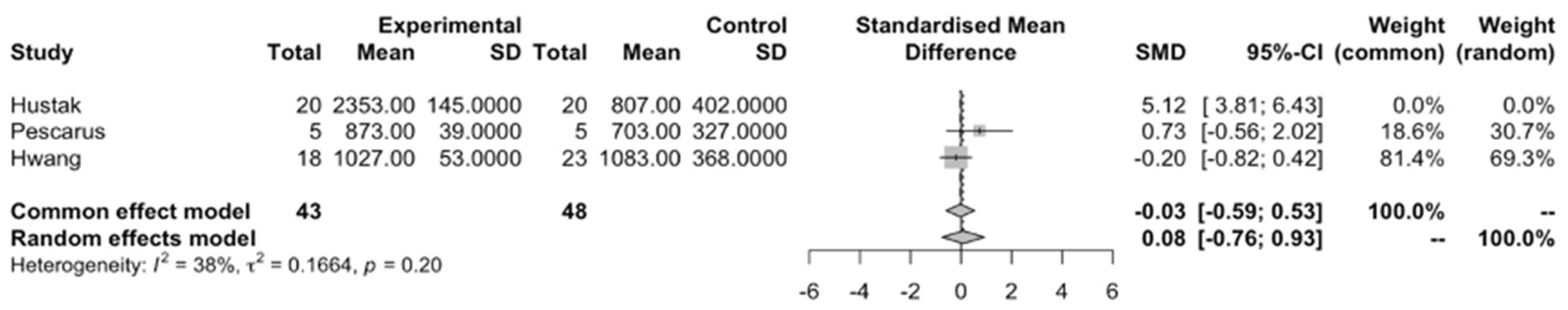

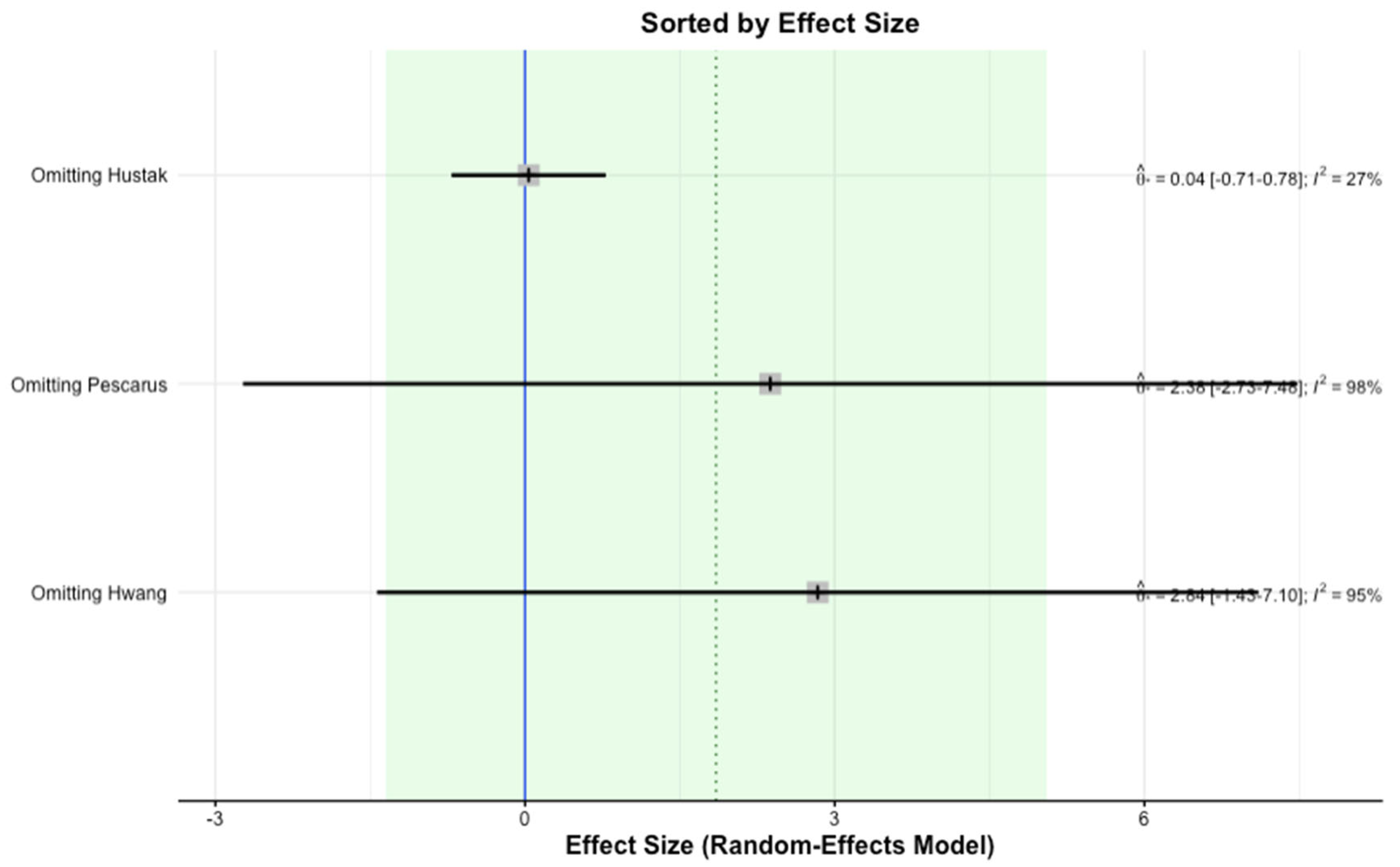

p < 0.0001). When performing the leave-one-out study, omitting the study by Hustak et. al. in the cost analysis showed a decrease in heterogeneity, reducing the Tau2 (0.13), I2 (38%), and Q test (1.62; df:1;

p = 0.2) and showing a consistent effect size without a statistical difference, as depicted in

Figure 4.

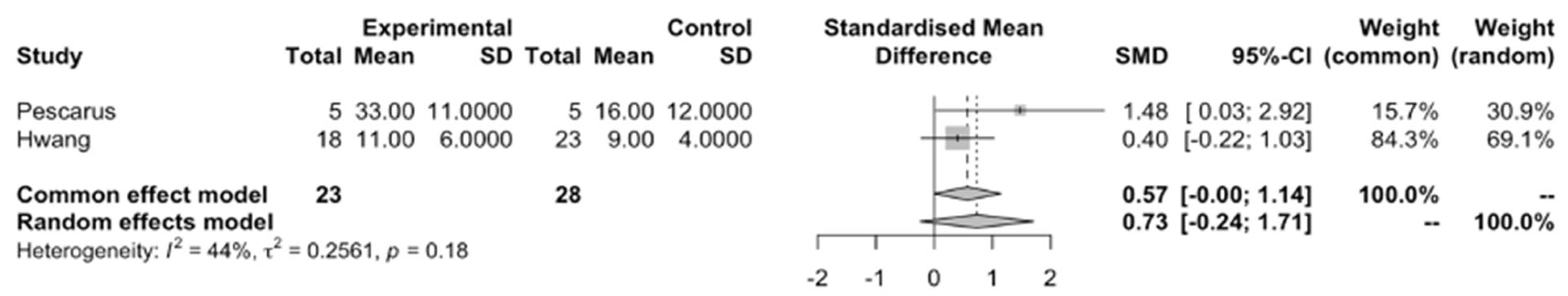

The time difference between studies did not show any statistical difference (SMD −0.73; CI: −170 to 0.23;

p = 0.13), as depicted in

Figure 5, and showed heterogeneity with tau2 (0.25), I2 (44%), and Q tests (1.8; df:1;

p = 0.18). Two of the studies did not have any complications, and one study reported one complication of chronic cough (4.3%) in the endoscopic suture group and two complications (mucosal injury due to misfired clip and mucosotomy leak) (11.1%) in the endoscopic clipping group.

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive search of the following databases, as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards, was conducted from inception to 8 December 2023: MEDLINE via PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Clinicaltrials.gov, and Cochrane Central Register for Controlled Trials. Additionally, a screening of key references/bibliographic lists for more studies was performed. The search strategy employed a combination of keywords and MESH terms, including “POEM”, “Pyloromyotomy”, “EndoCLIP”, “Endoscopic Suture”, and their derivatives (

Supplementary Material S1). All of the articles in English were included for screening.

3.2. Selection Process

Upon the completion of the search process, all results were exported to Rayyan web software (Rayyan Systems Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts, UK), where duplicates were removed via Rayyan’s duplicate detection algorithms. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of the identified studies against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full-text articles were obtained for studies that potentially met the inclusion criteria or where there was uncertainty. Disputes were resolved by a third senior author (RA).

3.3. Study Definitions

Endoscopic clipping was defined as the use of single-use preloaded metal clips for the closure of a mucosotomy without the need for an adjective closure device. Endoscopic suturing was defined as the closure of a mucosotomy using the OverStitch™ (Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, TX, USA) device.

3.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included all of the studies that involved adult patients aged 18 or older undergoing E-POEM or G-POEM and compared the effectiveness and outcomes of endoscopic clipping versus endoscopic sutures in mucosotomy closure. Our inclusion criteria comprised relevant observational studies, prospective studies, case-control studies, randomized studies, and abstracts. We excluded studies on animal subjects, case reports, case series with single intervention, editorials, guidelines, and review articles. Additionally, we excluded the use of OTSC, endoloops, and fibrin glue from the analysis. In cases of multiple publications from the same cohort and/or overlapping cohorts, data from the more recent and/or most appropriate comprehensive report were included. The quality of the included studies was assessed by the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (

Supplementary Material S2). Given the limited number of published studies on this topic, we included abstracts to enhance the robustness of the meta-analysis by incorporating all available data. This approach ensures a more comprehensive synthesis of evidence, allowing for a more meaningful evaluation of the comparative effectiveness of these closure techniques.

3.5. Data Extraction and Study Outcomes

The results were tabulated using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmont, WA, USA). The extracted data items included author names, the year of publication, the type of study design, POEM type, the total number of patients, patient demographics, and the details of interventions, as well as outcomes. The primary outcome was the technical success rate. The secondary outcomes were the cost of the procedure, time for the procedure, length of stay, and complications in the endoscopic clipping group and endoscopic suturing group.

3.6. Statistical Analysis and Bias Assessment

This meta-analysis was performed in strict accordance with the relevant requirements of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. The meta-analysis was performed by using R Software version 023.09.1+494 (2023.09.1+494[e1]) to calculate the effect size [

8]. Effect sizes were presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The random-effects model was used for a pooling analysis to compensate for the heterogeneity of the studies [

9,

10]. Interstudy heterogeneity was explored quantitatively by using Cochran’s Q and I

2 statistics. In this regard, I

2 ≥ 50% and ≥75% indicated substantial and considerable heterogeneity, respectively. A sensitivity analysis was conducted using a leave-one-out analysis to assess whether any individual study exerted a particular influence on the overall effect size [

11]. Potential publication bias was detected using visual inspection of the funnel plot and, if possible, Egger’s weighted regression tests.

p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant [

12,

13].

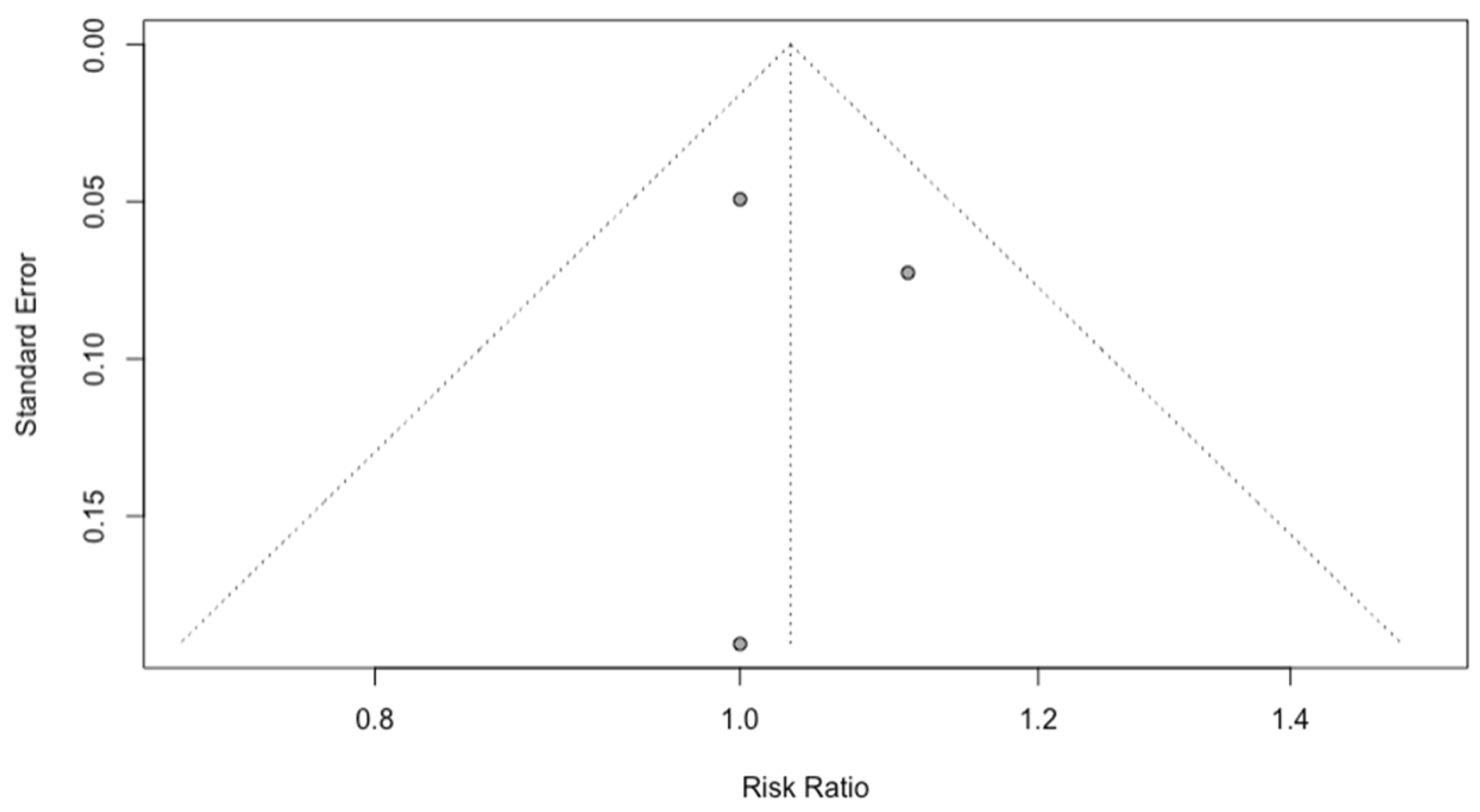

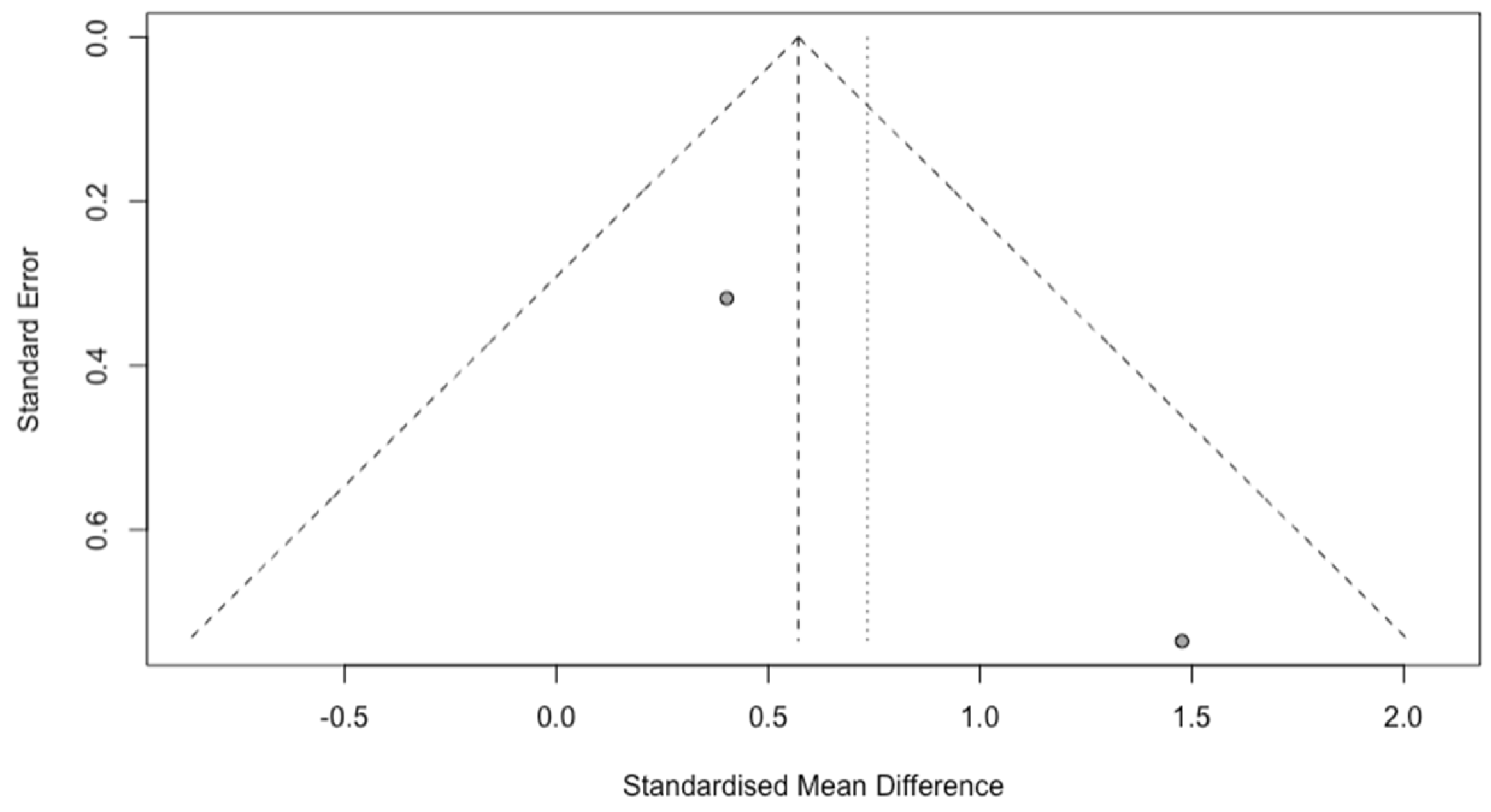

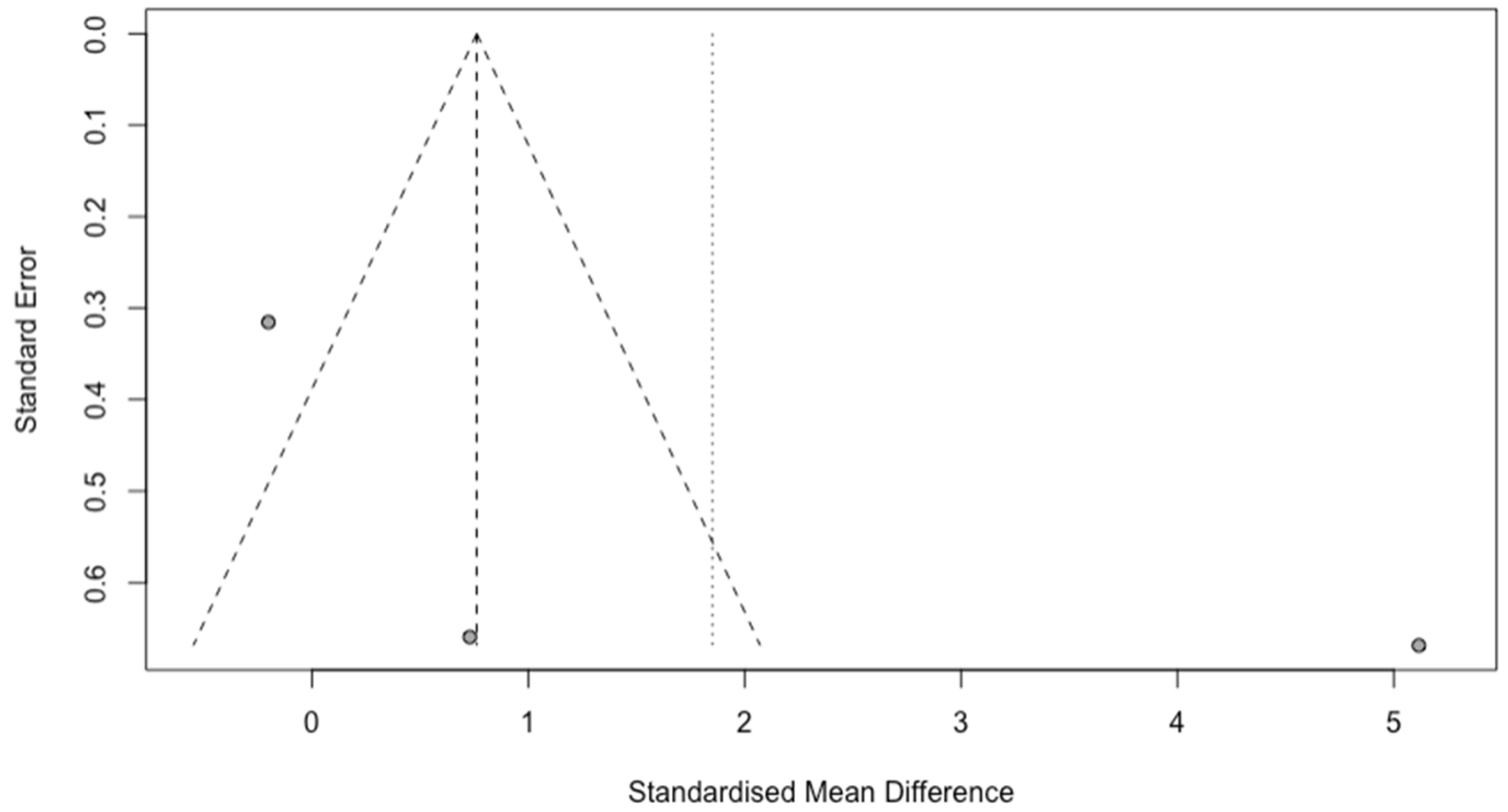

A total of three studies were evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for observational studies [

14]. Funnel plots were created to assess publication bias; the funnel plots of the procedure success rates and time variables showed symmetry (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7), and the funnel plot of cost between interventions showed asymmetry (

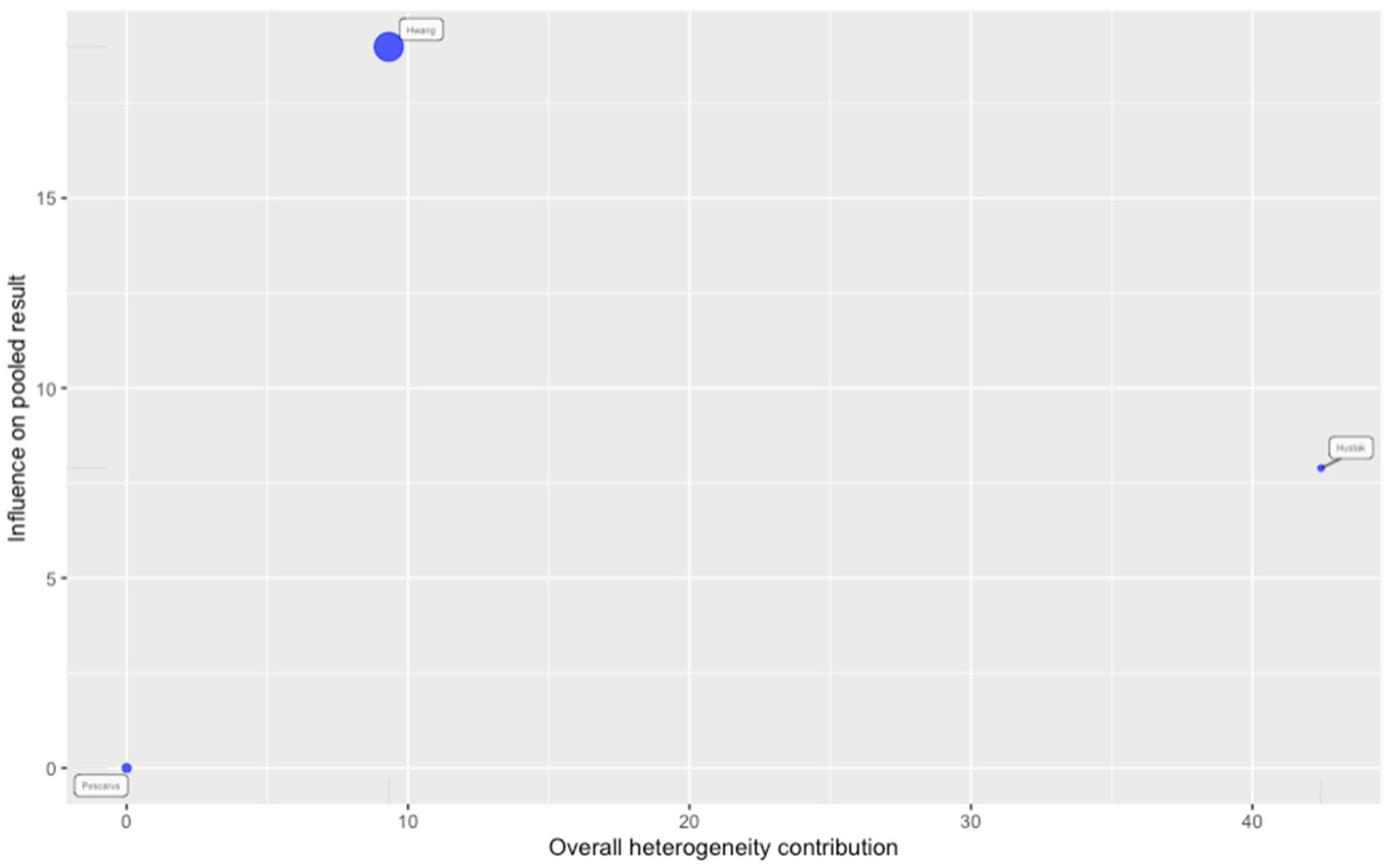

Figure 8). The Egger regression test to measure and possibly minimize publication bias was not possible due to the number of articles (<10 articles), but the leave-one-out and inference analyses showed that article number 1 was impacting the heterogeneity of the overall analysis, as shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

4. Discussion

With the increasing popularity of E-POEM and G-POEM for the management of esophageal motility disorders and refractory gastroparesis, respectively, due to their safety and minimal invasiveness, many centers have adapted these techniques [

15]. One of the most important aspects of the procedure is the appropriate closure of the mucosal entry site. Most centers use endoscopic clips for the closure of the mucosectomy due to their familiarity and ease of use [

16]. Some studies have tested the use of the Overstitch endoscopic suturing device (Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, TX, USA) for the closure of mucosal defects after ESD4 [

17,

18,

19]. The endoclips used across the studies included in the analysis are Resolution 360™ (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA), Quick Clips™ (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and Instinct Clips™ (Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) [

4,

18,

19].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of included studies.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Year | Study Type | POEM Type | Indication | Age Suture

(Years)

(Mean ± SD) | Age Clips

(Years)

(Mean ± SD) | Total Patients | Endoscopic Suture

(Number of Patients) | Endoscopic Clipping

(Number of Patients) |

|---|

| Hustak [4] | 2022 | Prospective | G-POEM | Refractory GP | 44 ± 14.8 | 51.1 ± 13.2 | 40 | 20 | 20 |

| Pescarus [18] | 2015 | Case-Control | E-POEM | Achalasia | 72.2 ± 11.4 | 69.6 ± 9.9 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| Hwang [19] | 2019 | Retrospective (Abstract only) | E-POEM | Achalasia | 51 ± 17 | 51 ± 17 | 41 | 23 | 18 |

Table 2.

Technical success and outcomes of studies included in the analysis.

Table 2.

Technical success and outcomes of studies included in the analysis.

| Author | Year | Total Suture | Total Clips | Suture Successful Closure | Clips Successful Closure | Suture Cost (Instrument) in USD a | Clips Cost (Instrument) in USD a | Suture Closure Time (Mins) | Clips Closure Time (Mins) | Suture Complications | Clips Complications | Post Procedure Days Discharge Suture | Post Procedure Days Discharge Clips |

|---|

Hustak

[4] | 2022 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 18 | 2353 ± 145 | 807 ± 402 | 14.1 (5–21) | 9.8 (4–20) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1–4) (Median) | 2 (1–7) (Median) |

Pescarus

[18] | 2015 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 873 ± 39 | 703 ± 327 | 33 ± 11 | 16 ± 12 | 0 | 0 | 1.8 ± 1.3 (Mean ± SD) | 1 ± 0 (Mean ± SD) |

Hwang

[19] | 2019 | 23 | 18 | 23 | 18 | 1027 ± 53 | 1083 ± 368 | 11 ± 6 | 9 ± 4 | 1 b | 2 c | x | x |

The results of our meta-analysis do not show any statistically significant difference between the technical success rates of endoscopic clipping and endoscopic suturing in the closure of mucosotomy after POEM/G-POEM. Additionally, there was no statistically significant difference in the cost of endoscopic clipping and endoscopic suturing or the time for the procedures. The results of the success rates of the meta-analysis comparing two procedures are consistent with the results of individual studies. Only one study by Hustak et al. had successful clip closure in 90% of patients as compared to 100% in patients with endoscopic suture closure; however, the difference was not statistically significant [

4]. In case of inadequate closure using endoscopic clipping, alternative closure methods like endoscopic suturing (KING Closure, OVESCO Clip) should be available as backups [

4].

There was no statistically significant difference in the cost of the treatment options for mucosotomy closure. However, the study by Hustak et al. on mucosotomy closure in G-POEM showed endoscopic clipping to be significantly cheaper compared to endoscopic sutures [

4]. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in the cost of two procedures in patients undergoing E-POEM. This difference could be due to the difference in the number of clips and sutures used for the successful closure of the mucosotomy. It is also important to note that there are variations in the factors taken into consideration for cost analysis among the studies included. The prices for endoscopic clips, as well as instrument-related costs for clipping and suturing, will also vary based on the hospital system. This is evident by the difference in the instrument cost of endoscopic clipping vs. endoscopic suturing (703 ± 327 vs. 873 ± 39;

p < 0.169) as compared to the total operating room time cost of endoscopic clipping vs. suturing (799 ± 596 vs. 1648 ± 548;

p = 0.044) in the study by Pescarus et al. [

18]. Based on reporting by Kantsevoy el al., the cost of the Overstitch suturing device is

$599, and the cost of each suture with cinch is

$138. The study by Liaquat et al. reported

$150 as the cost of each endoscopic clip [

20].

There was no significant difference in the procedure time between endoscopic clipping and endoscopic suturing, which is consistent with two studies in the meta-analysis. The study by Pescarus et al. showed a significantly longer procedure time for endoscopic suturing as compared to endoscopic clipping (33 ± 11 min vs. 16 ± 12 min;

p < 0.044) [

18]. This difference in timing between procedures across studies could be due to variation from physician to physician, as well as the level of expertise of the person performing the procedure. The small number of subjects in each study, as well as the small number of studies included in the meta-analysis, could also have led to the lack of statistical significance in the results.

The length of stay is comparable in two studies, and the data is not available in one study. The median length of stay in the study by Hustak et al. is 2 in both groups, ranging from 1–4 days in the suturing group to 1–7 days in the clipping group [

4]. The mean length of stay in the study by Pescarus et al. is 1.8 days with a SD of 1.3 days in the suture group and 1 day with a SD of 0 in the clips group [

18]. The length of stay can be affected by intra-procedure and post-procedure complications, as well as other comorbidities. Some common endoscopic complications are bleeding, mucosal perforation, capnoperitoneum, and peritonitis/mediastinitis from leaked contents [

2,

21]. Perforation can lead to peritonitis/mediastinitis, which can lead to sepsis during the post-procedure period. The closure of a mucosotomy with large diastasis between the defects can be cumbersome with the clips and might require the placement of multiple clips [

17]. The limited jaw span of the endoclips can limit their use in the closure of the mucosectomy. Endoscopic sutures can be useful in tissue approximation using continuous suturing lines or separate stitches with the possibility of reloading the device with a new needle [

17].

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first meta-analysis comparing the technical success rates and outcomes of endoscopic clipping and endoscopic suturing for the closure of mucosotomy during E-POEM/G-POEM. While the results of this meta-analysis suggest a potential shift in the management of mucosotomy closure towards better success rates and lower risks of complications using endoscopic sutures, the decision of using clips or sutures for mucosotomy closure should be made based on the physician’s expertise and the nature of the mucosotomy. Additionally, it will be interesting to explore long-term complications in patients undergoing the procedure, as well as the outcomes based on the level of expertise of the physician.

This meta-analysis has several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the small sample size (three studies, 91 patients) limits its statistical power, increasing the risk of type II errors and potentially explaining the lack of significant differences observed, rather than confirming true equivalence between endoscopic suturing and clipping. Heterogeneity was present, especially in cost outcomes, and although a random-effects model was used to adjust for variability, the small sample size makes it difficult to fully explore the reasons for these differences. One study had a major influence on cost-related outcomes, as identified by sensitivity analysis. Additionally, due to the limited number of studies, we could not formally test for publication bias using Egger’s test, though visual inspection suggested possible bias in cost outcomes. Lastly, all included studies were observational, which may introduce some bias in patient selection and outcome reporting. It is important to highlight that one of the studies was high quality and one of the studies was fair quality based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. The abstract lacked adequate details to assess the quality of the study. The limited number of studies, as well as participants, can affect the broader applicability of the results. Nevertheless, being the only meta-analysis on this topic, our data add valuable information on the clinical outcome of EUS-BD in this patient population.

5. Conclusions

In summary, both endoscopic suturing and clipping are effective for achieving adequate closure of mucosectomy defects. However, rescue closure methods should be available in case of failure, particularly for endoscopic clipping, as the reported technical success rate of endoscopic suturing remains 100% in the included studies. While suturing may be more expensive and time-consuming, its effectiveness may improve with operator experience. Additionally, complications were rare but occurred in both groups, with minor adverse events reported, including chronic cough in the suturing group and mucosal injury or leakage in the clipping group.

From a clinical perspective, the choice between clipping and suturing may depend on patient-specific factors, lesion size, and equipment availability. Clipping is faster and more cost-effective, making it a suitable first-line option, particularly for smaller defects. However, in cases of larger or more complex defects, suturing may provide a more durable closure despite its higher cost and longer procedure time. Endoscopist experience also plays a critical role, as proficiency with suturing may improve efficiency and reduce procedure duration over time. Although these differences may have limited clinical significance in the current data, further large-scale randomized controlled studies are needed to refine the indications for each method and optimize their role in routine practice.