1. Introduction

Globally, an estimated 58 million people have chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, with about 1.5 million new infections occurring per year [

1]. HCV can cause chronic hepatitis, which can induce a serious, lifelong illness, including liver cirrhosis and cancer, from which approximately 290,000 people die worldwide [

1]. In Japan, an estimated 100,000–150,000 people have HCV infection, from which over 3000 die annually [

2,

3].

Antiviral medicines, including pan-genotypic direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), can cure more than 95% of individuals with HCV infection [

1,

4]. However, access to diagnosis and treatment is low. It is estimated that only 21% (15.2 million) of individuals know of their diagnosis, and of those diagnosed with chronic HCV infection, around 62% (9.4 million) individuals had been treated with DAAs [

1]. The same concern exists in Japan, where it is estimated that 300,000 HCV-infected individuals remain unaware of their infection status [

5].

In Japanese hospitals, patients undergoing invasive procedures or surgery are usually screened for anti-HCV antibodies. However, only 14–18% of possible HCV careers are referred to a hepatologist [

6,

7,

8]. The Japanese government has requested that the results of the screening tests should be properly explained to patients, and a few hospitals have developed alert systems to promote the referral of positive anti-HCV-antibody patients to the department of hepatology [

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, such systems to promote referral to hepatologists have still not been fully investigated and discussed.

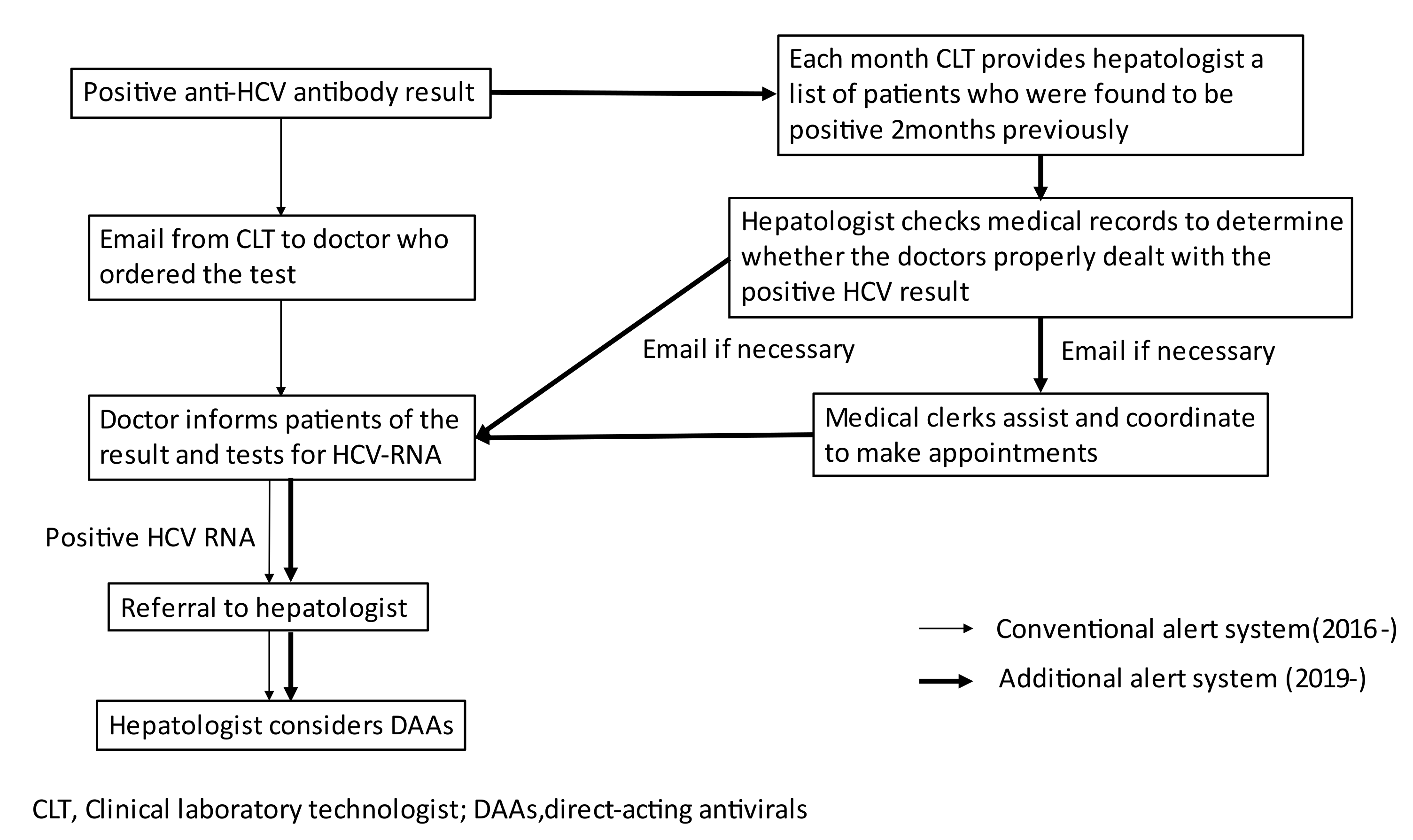

Since 2016, clinical laboratory technologists in our hospital have immediately emailed doctors to inform them of the results of positive anti-HCV antibody tests that they ordered anti-HCV antibody test, to request HCV-RNA testing if needed, and to refer HCV-RNA positive patients to hepatologists. The tests that are ordered by doctors in the department of gastroenterology and those that are conducted during medical checkups are excluded from the alert system. However, we found that this alert system had not functioned well; thus, some patients may have never either known about their HCV infection status or been properly treated.

Therefore, we developed a double alert system to promote HCV-RNA testing for anti-HCV-antibody-positive patients and the referral of HCV-RNA-positive patients to hepatologists by email, which has been implemented since January 2019. The aim of this study was to investigate the usefulness of the double alert system by comparing the number of anti-HCV-antibody-positive patients who underwent HCV-RNA testing before and after the intervention.

3. Results

Among the 10,784 and 12,560 patients who received an anti-HCV antibody test in the pre-intervention period and post-intervention period, respectively, 241 (2.2%) and 269 (2.1%) were found to be positive; the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.654). In the pre-intervention period and post-intervention period, respectively, 92 and 103 patients were excluded because tests were ordered by both doctors in the department of gastroenterology and based on a medical checkup, and overlapped. In addition, among the remaining 149 and 166 patients in the pre-intervention period and post-intervention period, respectively, 19 patients and 15 patients who were under follow-up in the department of gastroenterology in our hospital were also excluded, respectively. Finally, 130 patients managed in the pre-intervention period and 151 patients managed in the post-intervention period were included in this study; this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.714).

The baseline characteristics of the included patients before and after the introduction of the double alert system are shown in

Table 1. In the pre-intervention and post-intervention periods, 53 (40.7%) and 36 (23.8%) patients received anti-HCV antibody testing in an emergent situation, respectively; this difference was statistically significant (

p = 0.005). Furthermore, in the pre-intervention and post-intervention periods, 93 (71.6%) and 126 (83.4%) patients were outpatients, respectively, which was also a statistically significant difference (

p = 0.016). Other characteristics, including sex, age, and department, as well as related parameters, including the anti-HCV antibody titer, transaminase, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase, albumin, and platelet count, did not differ to a statistically significant extent.

A flowchart of 130 patients in the pre-intervention period who were included in this study is shown in

Figure 2. Of the 130 patients, 42 underwent HCV-RNA testing, 11 of these were found to be positive, and 31 were found to be negative. The medical records of the 88 patients (67.6%) in whom HCV-RNA was not tested were checked by a hepatologist. Subsequently, 52 patients were excluded (description of a past history of HCV,

n = 43; severe general condition,

n = 5; very old,

n = 2; direct consultation of hepatologist,

n = 1; explanation of results to the patient,

n = 1). It was not clear whether the remaining 36 patients knew of their positive result and had properly dealt with it. Of these 36 patients, 9 (25.0%) patients had an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of >30 IU/L, and 22 (61.1%) patients had an anti-HCV antibody titer of ≥4.0 S/CO. Then, 12 (9.2%) were judged to have probable chronic HCV hepatitis, while 23 were judged to not have probable chronic HCV hepatitis; one could not be properly evaluated due to missing data. In 27 (75%) out of 36 patients, anti-HCV testing was ordered by doctors who were not in an internal medicine department. Seven out of the 36 patients (19.4%) received anti-HCV testing in an emergent situation. Overall, 3 (2.3%) patients received DAAs and successfully achieved sustained virological response.

A flowchart of the 151 patients managed in the post-intervention period and who were included in this study is shown in

Figure 3. Among the 151 patients, 77 underwent HCV-RNA testing, 21 of whom were found to be positive, while 56 were found to be negative. There was a significant decrease in the number of patients in whom HCV-RNA was not tested after the first email alert (

p = 0.014). The medical records of the 74 patients (49.0%) in whom HCV-RNA was not tested were checked by a hepatologist. Subsequently, 49 patients were excluded (description of a past history of HCV,

n = 38; severe general condition,

n = 7; very old,

n = 2; direct consultation to hepatologists,

n = 2). It was not clear whether the remaining 25 patients knew of their positive result and had properly dealt with it. Therefore, the hepatologist sent emails to both the doctor and a medical clerk to inform them to conduct an HCV-RNA test and to refer HCV-RNA-positive patients to hepatologists. Of these 25 patients, 12 underwent HCV-RNA testing, 7 were found to be positive and 5 were found to be negative. It was not clear whether the remaining 13 patients knew of their positive result and had properly dealt with it. This number amounted to a statistically significant decrease in comparison to that before the introduction of the double alert system (

p < 0.001). Among the 13 patients, 4 (2.6%) were judged to have probable chronic HCV hepatitis, while 9 were judged to not have probable chronic HCV hepatitis. The number of anti-HCV-positive patients whose results were not properly handled showed a significant decrease after the introduction of the double alert system (

p = 0.034). Overall, 9 (5.9%) patients received DAAs and then successfully achieved sustained virological response. More patients received DAAs in the post-intervention period; however, the increase was not statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Two important clinical issues were noted in the present study: (1) a significant number of patients with probable chronic HCV hepatitis whose results were not properly handled were overlooked when the conventional single alert system was in place for screening anti-HCV antibody testing; and (2) the double alert system was useful for reducing the number of anti-HCV-antibody-positive patients whose results were not properly handled.

With regard to the first issue, the reported rate of referral to hepatologists for anti-HCV antibody screening was only 13–35% [

6,

8,

9,

10]. In the present study, we found that 36 out of 130 (27%) anti-HCV-antibody-positive patients may have not known about their results and not properly dealt with HCV even when the email alert system was in place. This result indicates that—unfortunately—the conventional single alert system had not functioned appropriately. There may be several factors hindering referral to hepatologists. (1) It may be hard for doctors to remember the positive results as patients with HCV infection are usually asymptomatic and it can scarcely influence the diagnosis and treatment of main diseases or conditions. (2) Non-hepatologists, especially physicians who are not internal medicine specialists, may not recognize or worry about HCV-related life-threatening complications, including liver cirrhosis, varices, and hepatocellular carcinoma. (3) Non-hepatologists, especially physicians who are not internal medicine specialists, may be unaccustomed to the extra work associated with HCV, including obtaining informed consent, ordering HCV-RNA tests, and issuing referrals, or they may feel that this work is complicated. Previous studies have shown that an ALT level of > 30 IU/L, a high anti-HCV titer, and undergoing testing at an internal medicine department were factors contributing to referral to hepatologists [

6,

7]. Our present study also showed that the majority of patients whose positive anti-HCV antibody results had not been properly dealt with were judged to not have probable chronic HCV hepatitis, as well as underwent anti-HCV-antibody testing by physicians who are not internal medicine specialists. These results indicate that intensive intervention, including an in-hospital alert system and education for non-hepatologists, especially those who are not internal medicine specialists, is required to promote referral to hepatologists.

Second, the double alert system is useful for reducing cases in which positive anti-HCV-antibody results (in screening anti-HCV antibody testing) are not properly handled. Based on the unsatisfactory results of the conventional alert system, we developed and introduced a double alert system, in which alerts were issued by a hepatologist (in addition to the conventional alert system in which alerts were issued by clinical laboratory technologists). The implementation of in-hospital alert systems has been attempted in several cases and their usefulness has been reported [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. All previous studies showed an increase in the rate of referral to hepatologists. The present study also showed the usefulness of the double alert system, which brought about a decrease in the number of patients in which positive anti-HCV- antibody results (probable CHC) were not properly handled, and a decrease in the number of anti-HCV-positive patients who did not undergo HCV-RNA testing after the first alert. As a result, more patients could receive optimal medical care from hepatologists, including DAA treatment, which can prevent serious HCV-related complications.

The previously reported alert systems [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] are roughly categorized into three types: (1) alert comments are automatically placed on electronic medical records, (2) alert comments are manually emailed to doctors who ordered the anti-HCV antibody test, and (3) a multi-disciplinary team coordinates or directory conducts patient intervention. Type 1 and 2 are simple and convenient, and the alert is easily noticeable. However, the alert may be ignored or forgotten, as HCV infection usually receives low priority in the screening situation. In particular, the impact of the alert may gradually weaken in comparison with the alert at the introduction of the system, as was demonstrated by the unsatisfactory results in the three years after the introduction of the conventional alert system. Therefore, monitoring of patients or patient intervention by a third party, such as the type 3 intervention, is needed when a type 1 and 2 alert system is introduced. Furthermore, increasing the number of referrals to hepatologists may place a burden on hepatologists. On the other hand, the type 3 system is ideal and is able to fully deal with anti-HCV-positive patients; however, it’s complicated and requires considerable labor and energy. The construction of systems that automatically place alerts on medical records may be associated with considerable cost.

Taking these merits and demerits into consideration, we developed the double alert system. This system has three advantages: (1) asking doctors to conduct HCV-RNA testing as a first step could limit the patients selected for referral to those who are HCV-RNA-positive, which can reduce the burden on hepatologists; (2) checking of anti-HCV-positive patients by a hepatologist two months after testing allows patients whose results have not been properly handled to be efficiently picked up and monitored, and issuing email alerts with a two months interval can remind doctors of a patient’s anti-HCV-antibody-positive status and the importance of HCV infection. (3) Assistance and coordination by medical clerks can reduce the complicated extra work that must be performed by doctors. Taken together, this can be a relatively simple, low-cost system that places less burden on medical staff and reduces the number of patients whose results are not properly handled. However, we found a weakness in this system. There were a few patients who no longer had any opportunity to visit our hospital or who had already transferred hospital when the hepatologist checked their medical records. In those cases, we had to contact the patients or the next hospitals to coordinate the next visit if needed. Shortening the interval at which medical records are checked may be a solution to this problem.

The present study was associated with some limitations. First, this was a retrospective, single-center study, with a relatively small population. Further prospective studies with a larger population are warranted to clarify the usefulness of the double alert system in the clinical setting. Second, a few patients with a past history of HCV might have been included among the patients with probable chronic HCV whose results were not properly handled, as this was judged based only on the description of their medical records.