Abstract

Despite the recognized benefits of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, uptake is still suboptimal in many countries. In addressing this issue, one important element that has not received sufficient attention is population preference. Our review provides a comprehensive summary of the up-to-date evidence relative to this topic. Four OVID databases were searched: Ovid MEDLINE® ALL, Biological Abstracts, CAB Abstracts, and Global Health. Among the 742 articles generated, 154 full texts were selected for a more thorough evaluation based on predefined inclusion criteria. Finally, 83 studies were included in our review. The general population preferred either colonoscopy as the most accurate test, or fecal occult blood test (FOBT) as the least invasive for CRC screening. The emerging blood test (SEPT9) and capsule colonoscopy (nanopill), with the potential to overcome the pitfalls of the available techniques, were also favored. Gender, age, race, screening experience, education and beliefs, the perceived risk of CRC, insurance, and health status influence one’s test preference. To improve uptake, CRC screening programs should consider offering test alternatives and tailoring the content and delivery of screening information to the public’s preferences. Other logistical measures in terms of the types of bowel preparation, gender of endoscopist, stool collection device, and reward for participants can also be useful.

1. Introduction

Worldwide, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed and the second most deadly cancer, with an estimation of 1.93 million new CRC cases and 0.94 million CRC-related deaths in 2020 []. Screening is an excellent preventive intervention to detect pre-cancerous polyps and tumors at an early stage and reduce the mortality and morbidity of CRC [,,]. Current international guidelines recommend two main screening methods for CRC: colonoscopy as the gold standard test and fecal occult blood tests (guaiac fecal occult blood test—gFOBT or fecal immunochemical test—iFOBT/FIT) as the standard first-line test for population-based CRC screening [,,,]. Other less common screening modalities include stool DNA test (sDNA), sigmoidoscopy, computed tomography colonography (CTC), barium enema, and capsule colonoscopy [,,].

Despite the recognized benefits that screening offers, CRC screening uptake around the world is still suboptimal, with the rates below 50% in many countries and regions [,,,]. Considerable efforts have been made to increase CRC screening uptake. However, most of the measures taken have only considered the perspectives of scientific literature and experts [,]. One important element that has not received adequate attention is the preference of the general population for CRC screening tests.

Previous studies have shown that individual preference for a specific test can influence a person’s decision to participate in screening [,,]. As a result, providing the screening population with their test of choice can increase screening uptake [,,]. One’s acceptance and utilization of a screening test depends highly on the person’s attitude and barriers, such as perceived test accuracy, the extent of invasiveness, discomfort, pain and risk reduction, the complexity of the screening procedure, the length of screening interval, preparation requirements, embarrassment, and stool aversion (stool-based tests) [,,,,,]. Notably, it has been observed that a segment of the population would rather forgo screening if their test of choice is not available [,,,]. Yet, most of the population-based CRC screening programs up to present only use one default first-line test for the entire screening population [].

In addition, prior evidence shows that the preferences of the target population for CRC screening tests have not been well understood and, in many cases, there is a great discrepancy between physicians’ perception of their patients’ preferences and their actual preferences []. In a study by Redwood et al. [], patients reported travel and bowel preparation as the main barriers to colonoscopy, while physicians thought that fear of pain and test invasiveness were the main barriers for their patients. The difference between patients and physicians in the ranking for other colonoscopy attributes were also noted, including concerns about anesthesia (29% vs. 72%), the need for dependent care (22% vs. 66%), embarrassment (18% vs. 57%)or whether the procedure is time-consuming (16% vs. 48%). Similarly, in a study by Ling et al. [], while the patients’ hierarchy of test preferences was FOBT (43%), followed by colonoscopy (40%), FOBT plus sigmoidoscopy (12%), barium enema (3%), and sigmoidoscopy alone (2%), physicians recommended FOBT plus sigmoidoscopy most often (54%), followed by FOBT (23%), sigmoidoscopy (15%), and colonoscopy (3%) (none recommended barium enema). Disagreement in test preference between patients and physicians can have a negative impact on patients’ willingness to adhere to screening and the outcome of their screening experiences [,]. Unfortunately, previous findings suggest that physicians are often unwilling to comply with patient preference when it differs from their own [,].

A number of reviews have synthesized the available information on the advantages and disadvantages of the available CRC screening tests from the perspectives of experts [,,,]. In the past fifteen years, many single studies have also attempted to investigate the preference of the general population for both the conventional and emerging CRC screening techniques; however, an up-to-date review on this topic is currently lacking []. In this review, we aim to systematically summarize the existing findings and evidence on (1) Population preferences for CRC screening tests and the main reasons for their choices; (2) Individuals’ characteristics that influence test preference; (3) The actual participation in screening in relation to the stated preferences; (4) The perceived barriers to a specific test and potential measures to address the barriers; and (5) Population’s willingness to pay for CRC screening. Knowledge stemming from this comprehensive review can be helpful to guide policies and interventions to increase CRC screening uptake.

2. Results

2.1. Population Preference for CRC Screening Tests

There are two prominent trends in population preference for CRC screening tests reported in previous studies: people preferred either the most accurate test (visual or structural test: colonoscopy) [,,,,,,,,,,,,] or the least invasive one (stool-based test: fecal occult blood test (FOBT) or stool DNA (sDNA) test) [,,,,,,,,]. While both tests are highly recommended by international guidelines [,,,], with colonoscopy recommended as the gold standard test and stool-based test (iFOBT or gFOBT) as the standard first-line test for population-based CRC screening, population preference for colonoscopy and stool-based tests, as well as the other available screening techniques, has not been systematically reviewed.

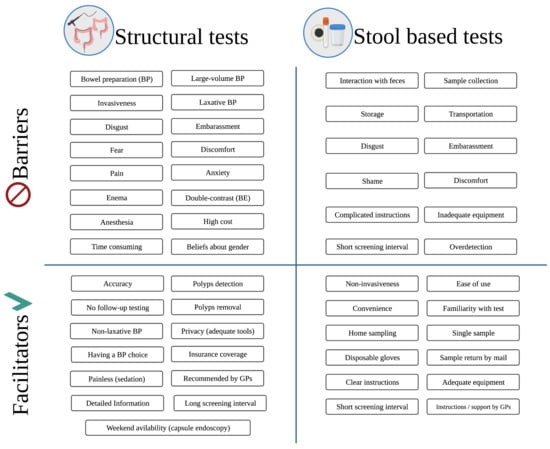

The following paragraphs, which are graphically summarized below, attempt to present population preference for CRC screening tests reported in literature (Table 1) and the reasons for their choices (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Studies that reported colonoscopy or stool-based test as population’s most preferred test and the corresponding percentages of respondents that selected the tests.

Figure 1.

Word clouds (in which the size of each word indicates its frequency or importance) of the most cited barriers and facilitators to colorectal cancer screening—Created with https://worditout.com/ (accessed on 20 August 2021). Definitions: Barriers = factors that could limit or restrict participation in colorectal cancer screening; Facilitators = factors that could either promote or be perceived as the most important attributes that facilitate decision making towards participation in colorectal cancer screening.

2.1.1. Preference for Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy was reported as the most preferred test in almost half of the studies regarding this topic that had been selected (13 studies, 4 countries: USA, South Korea, Jordan and Switzerland) [,,,,,,,,,,,,]. In these studies, colonoscopy was offered together with either only one other test (FOBT [,], CTC [], or multi-target stool DNA test []), or a group of the available tests including stool-based tests [] (FOBT [,,,,,,,] or sDNA [,]), sigmoidoscopy [,,,,,], CTC [,,], colon capsule [,], barium enema [,,,] and FOBT plus barium enema []. The percentages of individuals selecting colonoscopy as their first-choice test ranged from 41.1% to 80.6% [,,,,,,,,,,,,].

Accuracy was the most commonly reported reason for favoring colonoscopy [,,,,,]. Colonoscopy was seen as a thorough and revealing test [], with high sensitivity [,,] and could help to avoid false-positives []. Other valued attributes of colonoscopy included long screening intervals (normally 10 years) [,,], capacity to remove polyps [,], no need for a follow-up test [,], thoroughness of information provided [], and absence of pain thanks to anesthesia [].

Previous studies have also reported that individuals were more willing to undergo a colonoscopy if recommended by their physician [,]. At the same time, these studies indicate a strong tendency among physicians to practice and recommend colonoscopy over other tests. In a study by Wolf et al. (2016) [], 34% of the physicians responded that they did not have stool-based tests available, or they did have stool-based tests available but never recommended them to their patients. They were concerned that their patients would not complete the kits properly (e.g., not returning kits, improper sample storage) and the test accuracy was not sufficient, with a high rate of false positives and a certain rate of false negatives. A few answered that they could make no money when offering an FOBT or were not aware that FOBT was also recommended in the current guidelines [].

Notably, even in populations where the majority favored colonoscopy, there was always a subgroup that were strongly averse to colonoscopy and would not undergo CRC screening unless an alternative option was available [,,,]. The most common reasons for their aversion to colonoscopy were bowel preparation [], examination procedure [], invasiveness and pain/discomfort [,], fear of the procedure [], need for anesthesia [], cost and time consuming [] (See also Section 2.4.1).

2.1.2. Preference for Stool-Based Tests (FOBT and sDNA)

Stool-based tests were the second most commonly stated as population’s preferred tests for CRC screening, with FOBT more commonly reported (six studies, six countries (Isarael, Palestine, UK, USA, Australia, and Thailand)) [,,,,,] than sDNA (two studies, only in USA [,]). In these studies, FOBT was offered either with only colonoscopy [,,,] or with a group of the available tests including colonoscopy [,,], sigmoidoscopy [,,], and radiological tests [] (barium enema [,] and/or CTC []). sDNA testing was compared with colonoscopy [,,], FOBT [,,], sigmoidoscopy [], virtual colonoscopy [] and barium enema []. The percentages of individuals choosing stool-based test as their most favored screening test ranged from 38.2% to 84% [,,,,,,,,].

Test ease and convenience (simple sample collection and no need for preparation) was the most common reason stated among the respondents who selected stool-based test as their preferred test [,,,,,,,,]. An equally valued attribute of stool-based test was its non-invasiveness (less likely to cause harm/complication, less pain and discomfort) [,,,,,,].

The next commonly mentioned advantage of stool-based test is short interval (every one or two years) [,,]. Frequent testing was perceived to provide screening participants with reassurance of a good health [,,]. Many respondents also considered the non-invasive stool-test to be a preliminary test before other more invasive tests would be required [].

Another recognized benefit of stool-based tests is that they can usually be performed at home and distributed by mail, which enhances individuals’ privacy [,,,]. Van Dam et al. found that FOBT acceptance rate declined when individuals were required to take the test at hospital. The authors suggested two possible reasons including the lack of access to the testing centers and the absence of comfort compared to home sample collection [].

In some countries where FOBT was used in the population-based screening programs, the higher preference for FOBT could also be due to the population’s high familiarity with this test []. Interestingly, people who selected a stool-based test as their first-choice test tended to choose the alternative stool-based test, if offered, as their second-choice test over the other non-stool-based tests such as colonoscopy [,,] and CTC [,]. These individuals were often afraid of colonoscopy because of the use of laxatives for bowel preparation, sedation, or complications. They preferred a convenient and non-invasive test for routine screening even though the test is less accurate compared to colonoscopy [].

From the user’s perspective, sDNA and FOBT share many similarities since both are non-invasive stool-based tests which can be conveniently performed at home. However, Schroy et al. (2005) found that sDNA testing was rated as having simpler sample collection process compared to FOBT, which resulted in a higher level of comfort for participants in their study. The authors suggested that this might be due to the difference in the sample containers used between the two types. The sample container for sDNA could be directly mounted onto the toilet seat, so no direct manipulation of stool was required as it is, instead, for FOBT. Moreover, people also perceived a higher accuracy for sDNA compared to FOBT because of its more sophisticated and advanced technology []. Notably, sDNA assay has been suggested to have a high specificity (~100%) but only a modest sensitivity (~50%), which is higher than gFOBT but lower than FIT which also shares with sDNA the advantages of a stool-based test that were preferred by the population. Moreover, while FOBT (FIT in specific) is now the most commonly used test in population-based CRC screening [], sDNA is still uncommon in many countries and regions.

The most commonly reported reasons for not favoring stool-based tests are unpleasant sample collection [,], sample storage, and transportation [] (See also Section 2.4.2).

2.1.3. Preference for Computed Tomography Colonography (CTC)

CTC was reported to be preferred by the population over colonoscopy in 3 studies (conducted in the USA and UK) in which only the two tests were compared with each other [,,]. In these studies, respondents selected CTC over colonoscopy due to convenience [], less invasiveness [,], lower level of discomfort [], unpleasant experience with the previous colonoscopy [], embarrassment with colonoscopy [], primary care provider recommendation [], and safety concerns related to the individual’s health status [].

Participants found CTC more convenient than colonoscopy because CTC can be performed in a shorter examination time (a few minutes) [,,] and does not require sedation []; therefore, daily life activities are less interrupted, e.g., the person can drive to and from the procedure. In contrast, patients under sedation used in colonoscopy are advised against operating machinery for at least 24 h after the procedure [,]. Lack of transportation has been reported as an important practical barrier to CRC screening with colonoscopy [,,].

CTC has been reported to be a safer procedure compared to colonoscopy in terms of perforation rate. Unlike colonoscopy, which requires the insertion and maneuvering of a flexible tube to the proximal end of the colon, participants with CTC undergo gas insufflation using a small rectal catheter. Although extremely uncommon, perforation due to CTC can occur during the process of gas insufflation or the insertion of the rectal catheter through the rectal wall []. The rate of CTC-related perforation in literature ranged from 0.009% to 0.059% [,,]. In many cases [], CTC was performed for a diagnostic indication rather than screening. Thus, the rate of perforation related to screening CTC is expected to be even lower than the reported figures []. In comparison, the rate of colonoscopy-related perforation was about 0.1% [,,]. The risk is even higher when polypectomy is performed during colonoscopy [,].

In contrast, Jung et al. (2009) [] recorded a higher degree of abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort, and loss of dignity for CTC compared to colonoscopy. These findings defer from those of the previous studies in which the respondents preferred CTC over colonoscopy [,,]. According to Jung et al., this difference might be due to the quality of sedation. In their study, all participants were satisfied with sedation during colonoscopy, which might attribute to a higher level of contentment with colonoscopy and their preference for colonoscopy over CTC.

Another reason for the population’s preference for CTC over colonoscopy reported by Moawad et al. (2010), was the physician’s recommendation []. However, the authors explained that physicians at the study institution were more likely to recommend CTC to their patients because at the time, CTC was shown in two large studies to be as sensitive as colonoscopy in detecting polyps of ≥10 mm [,], and had been endorsed as an acceptable option for CRC screening by the American Cancer Society, American College of Radiology, and US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer []. Physicians’ willingness to recommend CTC over the other screening tests might also be due to the typical ease of referral, expedited follow-up for significant colonic (any polyp ≥ 6 mm) and extra-colonic findings, and the unique no-fee provision of care at the study institution as a military treatment facility [].

Two of the three studies that found the population’s preference for CTC over colonoscopy expressed concerns about potential selection bias that could have impacted their results. In Gareen et al.’s study (2015) [], the study subjects comprised those who chose to participate in the National CTC Trial, suggesting their willingness to undergo CTC. Similarly, in the study by Moawad et al. (2010), the study participants had already chosen to undergo CTC for screening when queried about their test preference [].

Reasons for people’s aversion to CTC include gas insufflation [], claustrophobic feeling [], the need to return for a colonoscopy for polyp removal when polyps are detected [,], abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort, and a loss of dignity []. While in colonoscopy, a patient is sedated and the procedure is typically performed in an isolated space, CTC is often performed (with colon inflation) on a fully conscious patient in a relatively open space, which may increase the patient’s anxiety, discomfort and loss of dignity []. In a study by Akerkar et al. [], participants who experienced a higher level of pain, discomfort and loss of dignity in the CTC group would be willing to wait for almost five weeks longer to have a colonoscopy instead of a CTC (See also Section 2.4.1).

2.1.4. Preference for Blood Test (SEPT9) and Capsule Colonoscopy (Nanopill)

SEPT9 and capsule colonoscopy have shown the potential to address the pitfalls of the current available tests with a high accuracy, test convenience, and a low level of harm. However, these tests are still new, and many factors need to be considered regarding their application in the context of population-based CRC screening, including guideline development, health economic considerations, and costs to participants.

In general, Australians expressed a preference for blood sampling over stool sampling because of sampling convenience [,,]. In the two studies conducted in Germany [] and the USA [], the SEPT9 blood test was the most preferred test by the study population when offered with the other available screening tests including FOBT, colonoscopy, and sigmoidoscopy. In the study by Adler et al. (2014), people favored SEPT9 since it could, at the same time, avoid fear, discomfort, and concern about bowel preparation and the colonoscopy procedure itself, and remove the aversion to the handling of stool samples. In addition, it offers a high accuracy []. The majority of the population have previously taken a blood test and have high trust of the test []. Almost no negative aspects of SEPT9, including fear of needles, were mentioned by the study participants. Although blood screening was preferred over FIT, the study by Zajac et al. (2016) showed that the likelihood of engaging in blood screening was significantly lower compared to home-based FIT. This underlines the fact that the population’s decision making for CRC screening is driven by multiple factors and test preference is only one of them [].

Groothuis-Oudshoorn et al. (2014) [] demonstrated the potential of capsule colonoscopy when used for CRC screening to reduce the percentage of people preferring no screening from 19.2% (when FIT was used) to 16.7%. The main reasons for which individuals preferred capsule colonoscopy were screening technique, sensitivity, and preparation (no preparation required). Capsule colonoscopy outperforms other tests due to its state-of-the-art technological basis and test convenience, however, at the expense of cost [].

2.2. Individuals’ Characteristics Influencing Test Preference

2.2.1. Gender

Women tended to prefer non-invasive test (FOBT) over the other more invasive tests (especially colonoscopy) [,,]. This aligns with the observations that men had a more positive attitude towards colonoscopy than women [] and women had lower rates of screening with colonoscopy than men [,]. Compared to men, women were more concerned about pain, discomfort, embarrassment, and complications related to colonoscopy and the possibility of cancer detection [,]. After experiencing colonoscopy, women also reported a higher level of pain [] and discomfort [], and lower willingness to undergo a future colonoscopy, compared to men [].

At the same time, more women than men expressed a preference for blood sampling [], and more women considered barium enema as their least-preferred test [].

2.2.2. Age

Previous studies have consistently shown a decrease in willingness to undergo colonoscopy with age [,,,], probably because of increasing concerns about sedation and complications []. Cho et al. (2017) [] also reported a significantly higher preference for FIT among elderly participants.

Compared to older people, younger people were more concerned about colon preparation and missing work due to colonoscopy []. In the study by Redwood et al. (2019), people aged < 60 years had a higher preference for sDNA than their older counterparts [].

2.2.3. Screening Experience

People with prior experience with colonoscopy were more willing to undergo a future colonoscopy [], and were less likely to prefer stool-based test over colonoscopy []. Fear and concerns about colonoscopy seem to decrease once the test has been experienced. The same trend is observed for stool-based tests. Previously screened subjects with stool-based tests were more likely to favor FOBT/sDNA compared to unscreened subjects [,,,]. This implies that when one selects a test for CRC screening, the person’s familiarity with the test can overcome the perceived barriers [].

2.2.4. Ethnicity

All the included studies that explored the association between ethnicity and preferences for CRC screening tests were conducted in the US. Caucasian Americans were more likely to prefer stool-based tests and SEPT9 [,,], while African Americans were more likely to prefer colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy [,]. When combining self-reported race and prior experience (with any CRC screening technique), Taber et al. (2014) [] found that unscreened African Americans tended to prefer colonoscopy, followed by screened Caucasian Americans and unscreened Hispanic Americans. In the same study, 43% of unscreened Caucasian Americans did not select colonoscopy as either their first- or second-choice test, suggesting a particular aversion to colonoscopy in this group.

2.2.5. Education Level and Belief

Two studies conducted in USA and Australia found that people with higher education preferred stool-based test more than those with lower education [,]. However, a Palestinian study found a lower acceptability of colonoscopy, but not FOBT, in those with education below secondary school level compared to those with higher education. Religious objection to screening and fatalistic beliefs were also linked with a lower acceptability of colonoscopy in this study []. The authors suggested that these results might be typical of Palestine since fatalism is a central belief in Islam. Fatalism has been shown to influence individuals’ attitudes towards cancer screening [,,]. Palestinians also seem to have a strong religious objection to colonoscopy compared to FOBT because colonoscopy is more invasive, intimidating and may contradict some of their religious values [].

In a Jordan study, preference for colonoscopy was also reported to be associated with a belief that CRC screening is costly []. People might assume that tests with higher costs have a higher accuracy and quality [].

2.2.6. Perceived Risk of CRC

Higher perceived risk of CRC or presence of symptoms were related to a greater willingness to undergo colonoscopy compared to less invasive tests (stool-based tests and CTC) [,,]. In contrast, average-risk individuals (with no symptoms; or a genetic test indicating an average risk) tended to choose FOBT as their most preferred test [].

2.2.7. Insurance Status

Uninsured people were more likely to prefer stool-based tests over colonoscopy compared to insured people []. This suggests cost-related barriers to CRC screening.

2.2.8. Health Status

People with fair or poor health status seemed to be less concerned about sensitivity than people with good to excellent health status and were less likely to select colonoscopy as their test of choice []. Although known as the most accurate test available, colonoscopy is also related to a higher risk of complications and therefore is not suitable for people with ill health.

2.3. Intention to Participate and Actual Participation in Relation to the Stated Preference

Previous studies have presented a consistent observation that participants who preferred colonoscopy were more likely to complete a colonoscopy compared to those preferring another test [,,]. Even when people stated that they preferred another test rather than colonoscopy, in their actual screening participation, many of them underwent colonoscopy. In fact, colonoscopy was the most commonly chosen test when people did not receive their preferred test [,,]. For example, in an English study (Wolf 2016), 78% of those who stated a preference for stool-based test remained unscreened. In the same study, regardless of the test chosen based on one’s preference, up to 80% of those screened were screened with colonoscopy. The two studies by Palmer et al. (2010) [] and Sandoval et al. (2021) [] also showed that individuals who were adherent to CRC screening were more likely to choose colonoscopy as their preferred test, while those who were non-adherent to CRC screening were more likely to choose stool-based tests. Participants with up-to-date screening were more concerned about test accuracy, unlike participants without up-to-date screening who were more concerned about the risks of colonoscopy and its costs [].

Other observations on individuals’ intention to participate or their actual participation came from single studies. Although people stated that they preferred blood sampling over stool sampling, home-based FOBT was more preferred than all of the blood test options (home blood, blood with one visit, blood with two visits, blood with three visits) []. The majority (91%) of those who underwent sDNA testing were willing to use the test again []. Annual capsule colonoscopy showed the potential to bring about a higher screening uptake compared to biennial FIT, but the difference was modest (from 75.8% to 78.8%) [].

2.4. Barriers to Participation in CRC Screening and Potential Addressing Measures

2.4.1. Visual (or Structural) Tests: Colonoscopy, Sigmoidoscopy, CTC and Capsule Colonoscopy

Visual technologies are recommended for screening the average-risk population by both the European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Colorectal Cancer Screening and Diagnosis, which recommends colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy as the current gold standard tests for CRC screening [], and the American Cancer Society guidelines which, together with the same tests, also recommends the use of emerging technologies such as CTC and capsule endoscopy [].

While the advantages of these visual techniques, colonoscopy in particular, are well known (e.g., high accuracy, the ability to screen and treat at the same time, longer screening intervals), they still present certain downsides (e.g., invasiveness, discomfort and the need for bowel preparation) that negatively affect screening compliance [].

For this reason, the following paragraphs attempt to collect and describe the main barriers and facilitators to screening with visual tests perceived by the public that were listed in literature.

Barriers to Screening with Visual Tests

Aside from logistical barriers to participate in screening, such as “lack of time” [,,], the literature clearly shows that important psychological barriers also exist. In fact, respondents of different ages, from different countries and healthcare systems, often express the same difficulties in participating in colonoscopy-based screening programs due to their perceived invasiveness [,,,,,,,,,,], which causes fear and anxiety [,] related to the procedure and preparation.

Embarrassment [,,,,] surrounding the procedure and the interaction with the healthcare professionals involved—especially in those cases in which the individual preference for the sex or, in some cases, ethnicity [] of the examiner is not met—are yet other main reported obstacles to participation.

The perceived invasiveness of colonoscopy is often expressed by participants as fear of pain [,,,,,] and discomfort [,], anxiety regarding sedation [,,,,] and preparation, fear of “insertion of tubes” [] and needles [], and concerns for privacy.

Feeling of “disgust” is also commonly reported [,]. Bowel preparation in particular, described as “horrible” from subjects interviewed by Dyer et al. [], represents a significant barrier to screening [,,,,,,,,]. Standard colonoscopy preparations are made of nonabsorbable solutions such as Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-electrolyte solutions (PEG-ELS) [] that, because of the laxative action [,,] and the large volume []—around 4 L—that must be ingested, can prevent the participants from completing the preparation [].

Radiological tests, alternative to colonoscopy, such as CTC and barium enema, present downsides as well. In fact, even if nowadays barium enema procedures are not often carried out, when requested as alternative to colonoscopy, they similarly require a laxative preparation and the procedure involves a tube that delivers the barium solution and air (double-contrast) into the colon [], which may cause the person to feel bloating and discomfort [,]. On the other hand, CTC also requires a laxative preparation and, in order to correctly visualize the colon, the distention of the colon by inserting air with an insufflator []. In this regard, Gareen et al. [], who investigated population’s preference for CTC and colonoscopy, found that participant-reported discomfort was more commonly worse than expected for CTC (32.9%) than for colonoscopy (5.0%) (p < 0.001). Moreover, women—more likely, in general, to express a preference for the sex of the examiner—were more likely to express a preference in this regard when having the CTC examination (44.5%) than when undergoing colonoscopy (24.3%).

Preference for Provider’s Gender

Because endoscopic procedures are often perceived as invasive and uncomfortable, it is understandable that the endoscopist’s gender can influence a person’s attitude towards screening. Among the studies included in this review, seven evaluated gender preferences among CRC screening participants [,,,,,,].

Females in particular appear to be more likely to express a preference for the sex of the examiner, as reported by Chong et al. [], who found that 70% of the female subjects (vs. 62.8% of males) who participated in their study expressed a gender preference; Zapatier et al. [], who found that 30.8% of the female subjects (vs. 20.4% of males) expressed a gender preference (p = 0.02); and Lachter et al. [], who found that 46% of the female subjects (vs. 22% of males) expressed a preference for a same-gender endoscopist (p = 0.086).

The most commonly cited reasons behind same gender preference are “feeling more comfortable” [], “less embarrassed” [] and the feeling, as reported by Menees et al. [], that “the same gender was more empathetic”, “a better listener” and also “technically better”. In fact, sometimes the same gender preference would even influence people’s willingness to pay (or pay more) and to wait in order to have their preference met [,].

In summary, evidence shows that participant’s “same gender” preference for the provider represents an important barrier that should be considered when organizing a screening program. However, not all individuals tend to express a gender preference, and some prefer an opposite gender endoscopist. The reason behind this, as reported by Khara et al. [], may lie in health practices and habits: the majority of them, predominantly females, have male primary care providers and male gynecologists.

Potential Addressing Measures for Increasing Participation with Visual Tests

Test attributes considered to be the most important and the hierarchy of information participants desire to receive represent a good exemplification of facilitators to CRC screening adherence. In this regard, respondents from the included studies give great importance to test accuracy [], high sensitivity for detecting polyps [,], and the opportunity to detect and treat them in the same procedure [,]. People want to be informed of the risks of the procedure, as well as practical aspects [] (with some asking for detailed, step by step explanations of what is going to happen and what to expect from the test []), and its benefits (e.g., how many cases of CRC or CRC-related deaths could be prevented by screening []). In general, the degree of satisfaction with information provided correlates with the degree of comfort during colonoscopy [].

In addition, addressing existing barriers such as the discomfort produced by bowel preparation could itself facilitate individuals’ participation; studies show that CRC screening participants have a preference for non-laxative [] and low-volume [] preparations. In fact, some of the included studies have investigated alternatives to the commonly used standard preparation PEG-ELS 4L, such as Sodium Phosphate (NaP) tablets [], Mannitol solutions [] and low-volume preparations such as Moviprep® AscPEG- 2L (PEG combined with ascorbic acid) and CitraFleet® PiMg (sodium picosulfate combined with magnesium citrate) [].

NaP tablets, for example, were preferred over the PEG solution by 66% of the 53 participants interviewed by Gurudu et al. []. In the study performed by Piñerúa-Gonsálvez et al. [], the PEG solution was also less chosen to be used again in future colonoscopies compared to the mannitol solution (71.4% of the individuals in the PEG group vs. 82.9% of the individuals in the mannitol group). Finally, Rodriíguez de Miguel et al. [] who, studied PEG-ELS 4L-related adverse effects compared to the low volume preparations on a cohort of 292 individuals, found that participants using PEG-ELS 4L required antiemetics more often compared to the AscPEG-2L and PiMg groups (22.4% vs. 2.1% and 8.2%, respectively; p < 0.0001). The AscPEG-2L and PiMg groups also presented with less nausea, thirst and headache than those treated with PEG-ELS 4L (12.5% vs. 23.5%, p = 0.047; 7.3% vs. 23.5%, p = 0.002 and 6.2% vs. 18.4%, p = 0.010, respectively). The evidence underlines how low-volume preparations, in general, appear to be better tolerated than the standard solution PEG-ELS 4L.

Moreover, having a choice among a range of colon-cleansing preparations for their next colonoscopy, as well as suggestions to alleviate the process, were consistently cited as facilitators [,].

Another major issue that prevents screening participation is concern for privacy. This, however, could be addressed by ensuring a protected environment and usage of adequate tools. For example, Aamar et al. [], investigated whether the use of a novel disposable patient garment (Privacy Pants®; Dignity Garment, Madison, MS, USA), which increases coverage, could reduce embarrassment and increase colonoscopy acceptance. Their results were noteworthy, with increased privacy—compared to the traditional gown—reported by 76% of the participants. This tool was associated with high rates of respect and satisfaction and decreased embarrassment during the procedure. The utilization this new disposable garment is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Illustrative image showing the utilization of the Privacy Pants® during colonoscopy—Retrieved from Dignity Garments (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tK8QplfW-ME (accessed on 1 September 2021)) [].

It should be noted that among the most appreciated attributes of visual tests, there is a set of features common to one particular technique: capsule endoscopy. This test does not require sedation and it is minimally invasive, therefore does not cause major embarrassment and discomfort that are frequently reported with the other structural techniques. Moreover, being available also during weekends, it appears more attractive to people with busy schedules []. In a study by Rex and Liberman [] (2012) involving 308 individuals, capsule colonoscopy (Check-Cap®) was chosen by 43% of individuals with a prior colonoscopy and by 69% of individuals who declined colonoscopy before (p < 0.0001). Furthermore, Chatrath and Rex [] who, in 2014, performed a similar investigation by proposing colonoscopy, FOBT, and Check-Cap as screening alternatives, found that Check-Cap was preferred to FOBT as an alternative to colonoscopy, most likely because of its higher sensitivity (80% for CRC and 50% for large polyps vs. 70% for CRC and 35% for large polyps) and ease of administration.

2.4.2. Stool-Based Tests: FIT/gFOBT and sDNA Test

Stool-based tests (FIT/gFOBT) and, with regards to the guidelines presently in place in the US, sDNA testing are currently recommended by international guidelines as the standard first-line tests for CRC screening in the average-risk population [,,]. However, similarly to their above-mentioned structural counterparts, these tests present certain disadvantages and barriers to participation. For example, feelings of embarrassment and discomfort and lower accuracy, which leads to higher false-positive rates (over-detection) compared to structural tests, are not always considered acceptable by participants [] and can negatively affect compliance [].

Barriers to Screening with Stool-Based Tests

The main barriers reported by individuals undergoing stool-based screenings are caused by “interaction with feces” [] that, generally, brings along feelings of “disgust” [,], “shame” [], “discomfort”, and “embarrassment” [].

Stool collection in particular, with troubles in “using paper to catch the sample”, “getting the stool sample into the tube” and “labelling the test”, seems to represent the biggest obstacle to screening participation with stool-based tests [,,].

In order to address the practical difficulties experienced by participants, some authors explored possible tools that could simplify participation. Among these are the so-called fecal collection devices (FCDs)—employing external collecting containers such as single-use flushable paper-based products and reusable plastic designs.

These, however, as reported by Morling et al. [], who investigated the preferences of 679 individuals, are less preferred than the standard container methods (44.6% found the sample collection with the FCD more difficult vs. only 38.4% found it easier). In contrast, in the study by Shin et al. [], the sampling bottle, consisting of “a small tube comprising a thin and long sampling probe with a grooved, spiraling tip and a twistable structure to open the cap” (typically employed in OC-Sensor quantitative FIT), was preferred over the conventional FOBT container (79.9% being satisfied with the sampling bottle vs. 73% with the conventional container). The intention to undergo future screening was also higher in the group preferring the sampling bottle compared to the conventional container (aOR 1.78 [1.28–2.48]). Although with rather contrasting opinions, small tube openings were generally disliked [,] and the use of such devices would decrease people’s willingness to participate.

Potential Addressing Measures for Increasing Participation with Stool-Based Tests

In line with what has been said, ease of use [,,,,,] was consistently cited as one of the main factors that could facilitate stool-based screening uptake, with participants requesting “clarity of instructions” [], “simpler instructions” [] and “simple and large font instructions” [].

The objective difficulties experienced by individuals in understanding and following kits’ instructions are witnessed by the need, expressed by many, of having a healthcare professional that could help them [,], for example, by performing the test in a mobile screening van or in hospital setting []. In general, “having an appointment with a healthcare professional” [] was perceived as a facilitator to taking the test, not only with the instructions and help provided, but also with the follow-up support [].

On the other hand, some authors have underlined how interaction with healthcare workers could cause embarrassment for some: Ellis et al. [] and Ramezani Doroh et al. [] reported that interviewed participants most often preferred their home as the sampling location. Similarly, Stoltzfus et al. [] reported how self-sampling, by overcoming healthcare access barriers, tends to help the people feel “in charge of their own care” resulting in a greater sense of independence and convenience.

On the same page, people’s preferences for returning samples were mixed. For example, 51% and 46.7% of the 820 participants interviewed by Ellis et al. [] preferred returning the stool sample by post and taking the sample to the general practitioner, respectively. In a study by Worthley et al. [], 5/44 responses regarding methods to encourage screening participation expressed a need for an “alternative to mail” to return stool samples.

In general, “limiting the need for interaction with feces” [,] is an important aspect of stool-based screening that could be addressed by “using tests that require only one sample” [,], “including disposable gloves” [], “including an antibacterial wipe and extra sheets of paper” [] and, in general, by providing “better equipment” for stool sample collection [].

A summary of the main perceived barriers and facilitators to both structural and stool-based tests is shown is included in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Main perceived barriers and facilitators to structural and stool-based tests—Created with https://biorender.com/ (accessed on 8 September 2021). Abbreviations: BP = bowel preparation; BE = barium enema; GP = general practitioners.

2.4.3. General Preferences

Other Barriers to CRC Screening in General

Regardless the type of test, the included articles show a specific trend in terms of perceived barriers to screening. In particular, feelings of embarrassment [,,,,,], discomfort [,,], disgust [,,,] and fear of pain [,,,,,,,] were common across various study populations undergoing different procedures.

Studies have found that these generalized feelings of anxiety and fear often translate into an attempt to avoid bad news. For example, a study conducted in Czech Republic by Kroupa et al. [] involving 498 individuals showed that 30.1% did not want to undergo screening tests for fear of a positive test result. Similarly, subjects interviewed by Gwede et al. [] preferred a “lighter tone” when receiving information regarding CRC disease and screening. In general, providing too many details, for example, regarding stool sampling methods [] or invasive follow-up tests [], were perceived as a barrier that could decrease screening participation.

Lack of interest [] and lack of time [,,], with the latter expressed, for example, as concern for “missing work” [], were also commonly cited as an obstacle to participation.

Other Potential Addressing Measures for Increasing Participation in CRC Screening

Conveniently, some of the above-mentioned participant-reported barriers to screening can be addressed by an equal number of participant-reported facilitators and suggestions. For example, one of the strategies that could be implemented to address people’s lack of interest for screening is, first of all, adequate information campaign. People’s suggestions in this regard include providing “major information before the offering of a test” [], more reminders [], billboards, commercials, newspaper articles [], personalized print materials such as books, magazines and other publications [], celebrity endorsement [] and “better publicity with a focus on sedation and reduction of inconvenience” [].

While people seem to dislike automated phone calls [], video decision aids (DAs) were appreciated by participants interviewed by Brackett et al. [], Coughlin et al. [], and Gwede et al. [], with the latter suggesting that a physician should serve as the narrator. In this regard, many studies reported that suggestions by a physician, particularly if this was the patient’s general practitioner, could positively influence screening participation [,,,,,,,,,,,,]. For example, participants interviewed by Gordon and Green [] reported that they would undergo screening “if the doctor told them why it is important for them to get screened”. Similarly, patients interviewed by Worthley et al. [] said that it was important for them to “understand their physician’s rationale for recommending a test over another”.

With regards to decision making, of the 2119 participants interviewed by Messina et al. [], 50% preferred to share decision making with their physician, 25% preferred to make decisions after considering their physician’s opinions, 16% preferred their physician to make all screening decisions and 5% preferred to make decisions alone. Similarly, of the 100 subjects interviewed by Calderwood et al. [] 53% said the physician and patient should equally share decision making, 20% preferred to make decisions alone, 13% said that the physician should make screening decisions, 7% said that decisions should be made mostly by the patient and another 7% preferred decisions to be made mostly by the physician. In contrast, most individuals interviewed by Ruffin et al. [] reported that the test choice should be up to the physician “because of their training, knowledge, and inclination to be directive”. In general, patients expressed a desire to be able to discuss with their provider about different screening options [,,].

On the subject of information campaign, a campaign launched in Lebanon in the international CRC month of March 2017 included a series of outreach events which employed a “giant inflatable colon model” as an interactive educational tool. Baassiri et al. [], by analyzing the data of 782 participants, found that touring the inflatable colon model significantly improved participants’ awareness and knowledge about CRC (81.2% after visiting the inflatable colon—vs. 19.2% before—knew the recommended age range for CRC screening), increased their willingness to participate in screening (78.6% vs. 70%) and their comfort discussing CRC screening (86.6% vs. 76.6%), (p < 0.001). Figure 4 displays an example of inflatable colon model in use in awareness campaigns.

Figure 4.

Giant inflatable colon on display at the Henry Ford Hospital as a part of Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month.—A Healthier Michigan (9 April 2021), Inflatable colon [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/healthiermi/13266807653 (accessed on 1 September 2021) [].

On the one hand, these results open a way to the new, interactive and informative tools to enhance people’s awareness of CRC screening and therefore, increase their screening uptake. On the other hand, lack of time remains an important issue preventing many individuals from participating in screening programs as well as attending these outreach events. In fact, different studies have underlined that “shorter travel time” to the hospitals or health clinics definitely facilitates participation in screening programs [,,].

Another important issue that should be addressed in order to enhance screening participation lies in healthcare accessibility [,,], particularly for women []. In this regard, participants suggested “improving existing relationships with providers”, “being given a referral for screening or specialist”, and “ease/speed of scheduling follow-up appointments”.

Finally, with regards to the test attributes considered as the most important to participants, the available literature indicates that, in general, the “ideal” test would be a low-cost, non-invasive test that does not require sedation, does not require preparation, does not involve radiation, has a low probability of pain and complications, is characterized by a high accuracy and significant mortality reduction and is offered with less frequency [,,,,,,,,,,,,]. Although creating a test that could meet these expectations is certainly challenging, it appears clear that, in order to maximize uptake in CRC screening programs, efforts of the scientific community should point in this direction.

2.5. Willingness to Pay, Costs and Rewards in CRC Screening

Healthcare access does not always come free of charge; for this reason, researchers have explored how costs of screening and health insurance coverage influence individual’s screening uptake [,,,,,]. For example, participants interviewed by both Ruffin et al. [] and Stoltzfus et al. [] reported that test cost and insurance coverage “would likely influence their motivation to use one screening modality over another”. Pignone et al. [] have pointed out that many would feel “discouraged from participating in a program where they had to bear large costs”. In this regard, in a study performed by Qumseya et al. [] in Palestine, out of 1352 respondents, 10% and 15% said they could not afford at all to pay for FOBT and colonoscopy, respectively.

In general, percentages of participants willing to pay out of pocket expenses for CRC screening vary across different settings. In a US study by Calderwood et al. [] involving 100 persons, when the participants were asked if they would still pick their first-choice test if it was not covered by healthcare insurance, 24% said “yes” regardless of the cost, 25% said “maybe” depending on the cost, 29% said “no”, and 22% were uncertain. Similarly, 83% of the 68 American participants interviewed by Ho et al. [] stated that they would not be willing to pay out-of-pocket the fees if insurance did not cover the test. In contrast, 91.7% of the 1240 participants interviewed by Zhou et al. [] in China, said that they were willing to pay for screening.

With regards to the amount that people would be willing to pay for CRC testing, studies included in this review reveal fluctuating trends [,,,,,,,,], with the mean values ranging around $100–200 for both structural (e.g., colonoscopy and CTC) and stool-based testing (e.g., FOBT and sDNA).

These analyses also underline that the differences in people’s willingness to pay depend not only on the type of test, but also on its attributes. For example, some individuals would be willing to pay more for a test that “removed polyps”, that can “avoid discomfort” by, for example, employing sedatives [] or that requires “longer intervals”, “no bowel preparation”, and causes “less complications” []. Participants would also pay more for a test with a 90% cancer detection rate, compared to 80% [] or, more in general, a test that found “most cancer”, compared to “some cancer” []. The specifications of these studies are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Population’s willingness to pay for specific colorectal cancer screening tests and/or features.

In general, those with a higher income, higher education level or a previous diagnosis of cancer were willing to pay more for screening [,,]. The participants’ gender—surprisingly, male in particular—was also significantly associated with willingness to pay for CRC screening [,,].

Since testing costs can pose a significant barrier to CRC screening participation, some programs have tried to promote community participation by financially “rewarding” screening participants. Authors have, in fact, described that individuals would be more likely to be screened if given a small ($10) [] or large (around $100) [,] reward. It appears that even small rewards (e.g., in the form of coupons) that could serve to repay gas expenses (for travelling to the hospital) or a day off work, especially in low-income communities, could serve as an important facilitator to screening participation.

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Despite it being of fundamental importance for the success of any CRC screening program, the general population’s preference in this context has not gained sufficient attention. Our study provides a comprehensive summary of the up-to-date knowledge on this topic. In this review, the PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses were adopted where applicable (e.g., search strategy, selection of studies and data extraction) []. However, it was not possible to assess the quality of the studies because of the diversity of study designs and populations.

It should be noted that a large amount of information provided in this review regards colonoscopy, the most commonly reported “preferred” test by the general population. The preponderance of this topic may be due to the large number of studies conducted in USA (42/83 of the studies included) where opportunistic colonoscopy screening is more common than in other countries (e.g., EU countries where many population-based CRC screening programs use FOBT) []. For this reason, in order to obtain a more complete understanding of population preferences concerning CRC screening tests, more studies should be conducted in a wider variety of settings.

Overall, the present study points out the main issues that need to be considered in the organization of a CRC screening program: information for participants on one hand, and logistical/organizational measures in place on the other.

With regards to information for participants, there are two main aspects that should be considered: individual previous knowledge/experience and the information that is provided to them. As for the latter, our review points out that the general population prefer receiving CRC screening information in more tailored and interactive ways, which also use a “lighter tone” in contrast to fear appeals. This requires a more welcoming and open environment for the target population to express their needs and concerns about CRC screening. Multicultural and multilingual outreach programs, and campaigns which enable individuals to feel respected and in charge of their own health, are also strongly desired. In this regard, suggestions and information directly provided by physicians, particularly if they are the patients’ general practitioners, appear to positively influence participation by providing a trustworthy/authoritative voice that can support decision making.

Moreover, providers who wish to advocate for one screening test option over another should be trained on how to properly educate people about its advantages, focusing, in particular, on features of the tests that people consider more important. These are either the test accuracy, the therapeutic effect and the low frequency required in the case of visual or structural tests [,,,] or, even if it comes with the price of a lower test accuracy, the convenience/ease of use and reduced invasiveness in the case of stool-based tests [,,]. Interestingly, both long screening intervals (ten-year), like those in colonoscopy-based programs [,,], and short screening intervals (one- or two-year), like those in stool-based programs [,,], could be perceived as advantages by the general population and could ultimately aid in increasing compliance. By providing more accurate results, colonoscopy-based programs require less frequent testing while more frequent testing employed in programs using stool-based tests can give participants more reassurance of well-being since they are screened every one or two years.

With regards to perceived invasiveness, it should be noted that a number of newer and promising screening technologies that employ biomarkers such as panels of methylated genes (e.g., SEPT9), microRNAs (miRNA) and protein panels, which can be performed on both blood, stool and, in some cases, urine samples, may become available on the market in the near future [,,]. However, there is currently not yet a clear recommendation about the clinical use of these tests. It may be possible, as we previously hypothesized [], that thanks to the features of ease-of-collection and non-invasiveness, these novel screening techniques, by meeting patient preferences, will improve screening uptake [,]. Since none of the retrieved studies (up to July 2021) have investigated population preferences for biomarker-based screening tests, further research is needed to validate this hypothesis.

Additionally, people perceive different test characteristics as being advantageous depending on their perceived risk of CRC [,]. Specific backgrounds, such as family history or prior detection of polyps, place a person at a higher risk for CRC. Those who know someone with CRC may also perceive their own risk of CRC to be higher than average []. Prior qualitative research has shown that people with a higher-than-average perceived risk tend to choose a more invasive screening test (colonoscopy) while people with an average perceived risk prefer a less invasive one (FOBT) [,]. These observations seem to reinforce the use of stool-based tests in average risk population-based CRC screening programs. However, in order to validate this hypothesis, further quantitative research conducted in screening settings is needed.

At the same time, due to the above-mentioned perceived barriers to CRC screening (Section 2.4), there is a relevant portion of individuals strongly reluctant towards colonoscopy or stool-based tests regardless of their previous or potential knowledge on the matter. Although both knowledge and beliefs have been shown to be associated with preference, beliefs tend to be more predictive of screening uptake, especially when they are supported by previous negative experiences []. As a consequence, the adaption of CRC screening programs to participants’ preferences by offering alternative CRC screening tests possesses a great potential to increase screening uptake.

In fact, when it comes to logistical/organizational measures in place, it seems that one of the most central issues to consider is the possibility to offer a range of options in terms of the screening tests (e.g., FOBT vs. colonoscopy vs. others) as well as the features of a specific test (e.g., high vs. low-volume or laxative vs. non-laxative bowel preparations for colonoscopy; or conventional kits vs. newer sample collection devices for stool-based tests).

Many studies corroborate this hypothesis, for example, Chatrath and Rex [] have reported that, among their study population, 76% of the subjects who declined colonoscopy were willing to undergo alternate forms of screening. Similarly, 97% of the participants in the study by Adler et al. [] who refused a colonoscopy were willing to accept a non-invasive test. Indeed, one third of people interviewed by Moawad et al. [] would not have undergone CRC screening if CTC had not been available as alternative to colonoscopy.

This data also underlines the fact that a preference for a specific test is limited to the options which are known to the people, e.g., if a person only knows about colonoscopy, it cannot be expected that the person prefers CTC or FIT instead. Clearly, providing complete, simple and clear information to the participant is of no less importance than providing screening alternatives.

In resource-limited settings where it is impractical to offer a range of options, other potential methods of boosting CRC screening uptake also exist. For example, if one test is offered as the default test but a portion of people persistently decline it, an alternative test can then be proposed to this specific subgroup. In these regards, the newer convenient screening technologies such as blood tests or capsule endoscopy that can be provided in the physician’s office could be useful to enhance screening participation.

In addition to providing alternatives, facilitating logistical aspects of a screening test can also improve participants’ feelings and attitudes towards it. Among these are initiatives that may help reduce healthcare access disparities and barriers, especially in lower socioeconomic status neighborhoods. For example, meeting participants’ preferences regarding the gender of endoscopist or systems of incentives and rewards that could encourage individuals in financial difficulties to prioritize their health.

Although most current guidelines recommend 50 years as the starting age for average risk CRC screening [,,], recent studies have shown an increase in CRC incidence among younger individuals [,,,]. In the US, both the guidelines of the American Cancer Society and US Preventive Services Task Force have, in 2018 and 2021, respectively, lowered the age for initiation of screening from 50 to 45 years [,]. Recent data (2021) from three European tertiary centers also suggests that the incidence of rectal cancers in adults aged ≤ 39 is increasing, with the disease likely to be more advanced at presentation compared to the older population (≥50 years). According to the authors, the lack of screening programs directed towards this age group may lead to late diagnosis and underestimation of symptoms [].

Since age has been shown to be associated with individual preference for screening test [,,,,,], the findings of our review need to be interpreted with caution in settings where younger adults (≤50 years) are also included in the CRC screening target group. In fact, further research is needed to investigate CRC screening preference in the younger population and identify the best approach that can optimize screening modalities across age groups []. For example, according to Mehta et al. (2021) [], the lowering of the starting age for screening in the US creates an opportunity to promote stool-based testing, particularly in individuals aged ≤50 years, who have a lower risk of CRC compared to the older counterparts.

Finally, prior evidence has shown that physicians may as well have a strong preference towards one CRC screening test over another, with a general tendency to recommend colonoscopy to their patients []. The findings of our review, however, demonstrate that, in order to boost screening participation, patients’ preferences and concerns need to be taken into account. We believe that, to guide their patients’ informed choice, physicians need to be, first and foremost, provided with up-to-date information about the available screening options, their attributes, and their perceived advantages and disadvantages. Therefore, changes in international guidelines and protocols that support and guide clinicians on these themes are needed to strengthen physicians’ role in facilitating patients’ decision-making process and increasing levels of CRC screening uptake.

To conclude, we trust the present collection of information and evidence can serve as a helpful updated guide of CRC screening population’s preferences, concerns and needs, meant for healthcare providers engaged in the organization of CRC screening programs.

4. Methods

On 25/07/2021 a comprehensive search was carried out in OVID and the following databases were used:

- Ovid MEDLINE® ALL;

- Biological Abstracts;

- CAB Abstracts;

- Global Health

The bibliographic search was conducted using the following string (Table 3).

Table 3.

Bibliographic search strategy.

The automatic search identified 1070 articles. Of these, 201 were excluded through automatic duplicates removal.

Once the duplicates had been removed, titles and abstracts obtained from the bibliographic search were screened in accordance with the PICo framework []:

- Population: General population or population at average risk for colorectal cancer (e.g., studies on subjects with genetic/familial risk or cancer patients only were excluded).

- Phenomena of interest: Preference, acceptability, compliance or willingness to undergo one or more screening tests, measured by survey, questionnaire or interview. Only direct measurement of participants’ preferences was taken into consideration (e.g., studies employing methodologies investigating factors associated with uptake as an indirect measurement of participants’ preferences were not included).

- Context: Colorectal cancer screening (i.e., studies on other types of gastrointestinal cancers were excluded).

- Other considerations: We restricted our search to only original articles (reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses and other types of secondary research were excluded), written in English and published between January 2005 and July 2021.

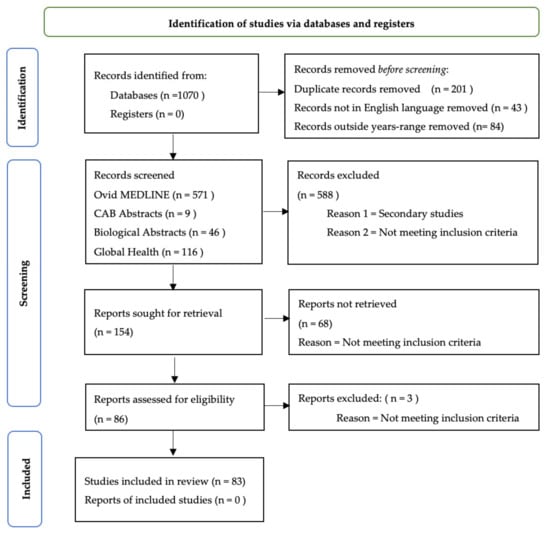

Of 742 titles/abstracts evaluated, 588 records—either secondary studies or those considered irrelevant—were removed. Subsequently, full texts of potentially eligible studies were assessed by applying the set of inclusion and exclusion criteria described above. Of 154 reports assessed for eligibility, 83 papers were finally included in this review. The whole selection and screening process is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Selection and Screening Process. Adapted from the PRISMA guidelines by Page et al. (2020) []. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.or (accessed on 1 August 2021).

Data from the selected studies were extracted and entered into an Excel sheet. The following information was collected (if relevant): Authors and year of publication; Study setting; Study design; Study population and/or Inclusion/Exclusion criteria; Sample size; Any statistical measure related to relevant outcomes; Main results and other potentially relevant information.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.N.T., G.V.H.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.F., T.N.T.; writing—review and editing, G.V.H., S.H., T.N.T., A.F., M.P.; visualization, A.F.; supervision, G.V.H., M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sofia Maria Tarchi (Medicine and Biomedical Engineering, Humanitas University and Politecnico di Milano) for providing language editing and proofreading.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Xi, Y.; Xu, P. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, H.; Stock, C.; Hoffmeister, M. Effect of screening sigmoidoscopy and screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ 2014, 348, g2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitson, P.; Glasziou, P.; Watson, E.; Towler, B.; Irwig, L. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): An update. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 1541–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgi Rossi, P.; Vicentini, M.; Sacchettini, C.; Di Felice, E.; Caroli, S.; Ferrari, F.; Mangone, L.; Pezzarossi, A.; Roncaglia, F.; Campari, C.; et al. Impact of Screening Program on Incidence of Colorectal Cancer: A Cohort Study in Italy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Karsa, L.; Patnick, J.; Segnan, N.; Atkin, W.; Halloran, S.; Lansdorp-Vogelaar, I.; Malila, N.; Minozzi, S.; Moss, S.; Quirke, P.; et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis: Overview and introduction to the full Supplement publication. Endoscopy 2013, 45, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.M.D.; Fontham, E.T.H.; Church, T.R.; Flowers, C.R.; Guerra, C.E.; LaMonte, S.J.; Etzioni, R.; McKenna, M.T.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Shih, Y.T.; et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 250–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segnan, N.; Patnick, J.; von Karsa, L. European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Colorectal Cancer Screening and Diagnosis, 1st ed.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ponti, A.; Anttila, A.; Ronco, G.; Senore, C.; Basu, P.; Segnan, N.; Tomatis, M.; Žakelj, M.P.; Dillner, J.; Fernan, M.; et al. Cancer Screening in the European Union. Report on the Implementation of Council Recommendation on Cancer Screening; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/major_chronic_diseases/docs/2017_cancerscreening_2ndreportimplementation_en.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2021).

- Geiger, T.M.; Ricciardi, R. Screening options and recommendations for colorectal cancer. Clin. Colon. Rectal Surg. 2009, 22, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, B.; Lieberman, D.A.; McFarland, B.; Smith, R.A.; Brooks, D.; Andrews, K.S.; Dash, C.; Giardiello, F.M.; Glick, S.; Levin, T.R.; et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: A joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2008, 58, 130–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, J.; Lew, J.B.; Feletto, E.; Holden, C.A.; Worthley, D.L.; Miller, C.; Canfell, K. Improving Australian National Bowel Cancer Screening Program outcomes through increased participation and cost-effective investment. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutel, G.; Duchange, N.; Lievre, A.; Orgerie, M.B.; Jullian, O.; Sancho-Garnier, H.; Darquy, S. Low participation in organized colorectal cancer screening in France: Underlying ethical issues. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 28, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, K.; O’Connell, K.; Anand, S.; Yakoubovitch, S.C.; Kwon, S.C.; de Latour, R.A.; Wallach, A.B.; Sherman, S.E.; Du, M.; Liang, P.S. Low Colorectal Cancer Screening Uptake and Persistent Disparities in an Underserved Urban Population. Cancer Prev. Res. 2020, 13, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, C.K.; Thomas, M.C.; McGregor, L.M.; von Wagner, C.; Raine, R. Understanding low colorectal cancer screening uptake in South Asian faith communities in England—A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, L.R.; Garcia, D.P.; Coelho, D.L.; De Lima, D.C.; Petroianu, A. How to improve colon cancer screening rates. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2015, 7, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougherty, M.K.; Brenner, A.T.; Crockett, S.D.; Gupta, S.; Wheeler, S.B.; Coker-Schwimmer, M.; Cubillos, L.; Malo, T.; Reuland, D.S. Evaluation of Interventions Intended to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates in the United States: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 1645–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inadomi, J.M.; Vijan, S.; Janz, N.K.; Fagerlin, A.; Thomas, J.P.; Lin, Y.V.; Munoz, R.; Lau, C.; Somsouk, M.; El-Nachef, N.; et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: A randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 575–582. [Google Scholar]

- Benning, T.M.; Dellaert, B.G.; Dirksen, C.D.; Severens, J.L. Preferences for potential innovations in non-invasive colorectal cancer screening: A labeled discrete choice experiment for a Dutch screening campaign. Acta Oncol. 2014, 53, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.C.; Ching, J.Y.; Chan, V.C.; Lam, T.Y.; Luk, A.K.; Ng, S.C.; Ng, S.S.; Sung, J.J. Informed choice vs. no choice in colorectal cancer screening tests: A prospective cohort study in real-life screening practice. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, D.A.; Johnson, F.R.; Phillips, K.A.; Marshall, J.K.; Thabane, L.; Kulin, N.A. Measuring patient preferences for colorectal cancer screening using a choice-format survey. Value Health 2007, 10, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, C.; Tangka, F.K.; Ekwueme, D.U.; Smith, J.L.; Guy, G.P., Jr.; Li, C.; Hauber, A.B. Stated Preference for Cancer Screening: A Systematic Review of the Literature, 1990–2013. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016, 13, E27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, L.; Hol, L.; de Bekker-Grob, E.W.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Kuipers, E.J.; Habbema, J.D.; Essink-Bot, M.L.; van Leerdam, M.E. What determines individuals’ preferences for colorectal cancer screening programmes? A discrete choice experiment. Eur. J. Cancer 2010, 46, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hol, L.; de Jonge, V.; van Leerdam, M.E.; van Ballegooijen, M.; Looman, C.W.N.; van Vuuren, A.J.; Reijerink, J.C.I.Y.; Habbema, J.D.F.; Essink-Bot, M.L.; Kuipers, E.J. Screening for colorectal cancer: Comparison of perceived test burden of guaiac-based faecal occult blood test, faecal immunochemical test and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Eur. J. Cancer 2010, 46, 2059–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.R.; Zajac, I.; Gregory, T.; Mehaffey, S.; Roosa, N.; Turnbull, D.; Esterman, A.; Young, G.P. Psychosocial variables associated with colorectal cancer screening in South Australia. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2011, 18, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapple, A.; Ziebland, S.; Hewitson, P.; McPherson, A. What affects the uptake of screening for bowel cancer using a faecal occult blood test (FOBt): A qualitative study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 2425–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, R.L.; Basch, C.E.; Zybert, P.; Basch, C.H.; Ullman, R.; Shmukler, C.; King, F.; Neugut, A.I. Patient Test Preference for Colorectal Cancer Screening and Screening Uptake in an Insured Urban Minority Population. J. Community Health 2016, 41, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moawad, F.J.; Maydonovitch, C.L.; Cullen, P.A.; Barlow, D.S.; Jenson, D.W.; Cash, B.D. CT colonography may improve colorectal cancer screening compliance. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2010, 195, 1118–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBourcy, A.C.; Lichtenberger, S.; Felton, S.; Butterfield, K.T.; Ahnen, D.J.; Denberg, T.D. Community-based preferences for stool cards versus colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatrath, H.; Rex, D.K. Potential screening benefit of a colorectal imaging capsule that does not require bowel preparation. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2014, 48, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreuders, E.H.; Ruco, A.; Rabeneck, L.; Schoen, R.E.; Sung, J.J.; Young, G.P.; Kuipers, E.J. Colorectal cancer screening: A global overview of existing programmes. Gut 2015, 64, 1637–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redwood, D.G.; Blake, I.D.; Provost, E.M.; Kisiel, J.B.; Sacco, F.D.; Ahlquist, D.A. Alaska native patient and provider perspectives on the multitarget stool DNA test compared with colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2019, 10, 2150132719884295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, B.S.; Moskowitz, M.A.; Wachs, D.; Pearson, B.; Schroy, P.C. Attitudes Toward Colorectal Cancer Screening Tests. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroy, P.C., 3rd; Duhovic, E.; Chen, C.A.; Heeren, T.C.; Lopez, W.; Apodaca, D.L.; Wong, J.B. Risk Stratification and Shared Decision Making for Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Med. Decis. Mak. 2016, 36, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQueen, A.; Bartholomew, L.K.; Greisinger, A.J.; Medina, G.G.; Hawley, S.T.; Haidet, P.; Bettencourt, J.L.; Shokar, N.K.; Ling, B.S.; Vernon, S.W. Behind closed doors: Physician-patient discussions about colorectal cancer screening. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimer, B.K.; Briss, P.A.; Zeller, P.K.; Chan, E.C.; Woolf, S.H. Informed decision making: What is its role in cancer screening? Cancer 2004, 101, 1214–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A.; Neefs, I.; Hoeck, S.; Peeters, M.; Van Hal, G. Towards Novel Non-Invasive Colorectal Cancer Screening Methods: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, I.A.; Noureddine, M. Colorectal cancer screening: An updated review of the available options. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 5086–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.R.; Aggarwal, A.; Imperiale, T.F. Colorectal Cancer Screening: Stool DNA and Other Noninvasive Modalities. Gut Liver 2016, 10, 15420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, E.J.; Rosch, T.; Bretthauer, M. Colorectal cancer screening—Optimizing current strategies and new directions. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanouni, A.; Smith, S.G.; Halligan, S.; Plumb, A.; Boone, D.; Yao, G.L.; Zhu, S.; Lilford, R.; Wardle, J.; von Wagner, C. Public preferences for colorectal cancer screening tests: A review of conjoint analysis studies. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2013, 10, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]