Effects of Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia on Self-Reported Sleep Parameters: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

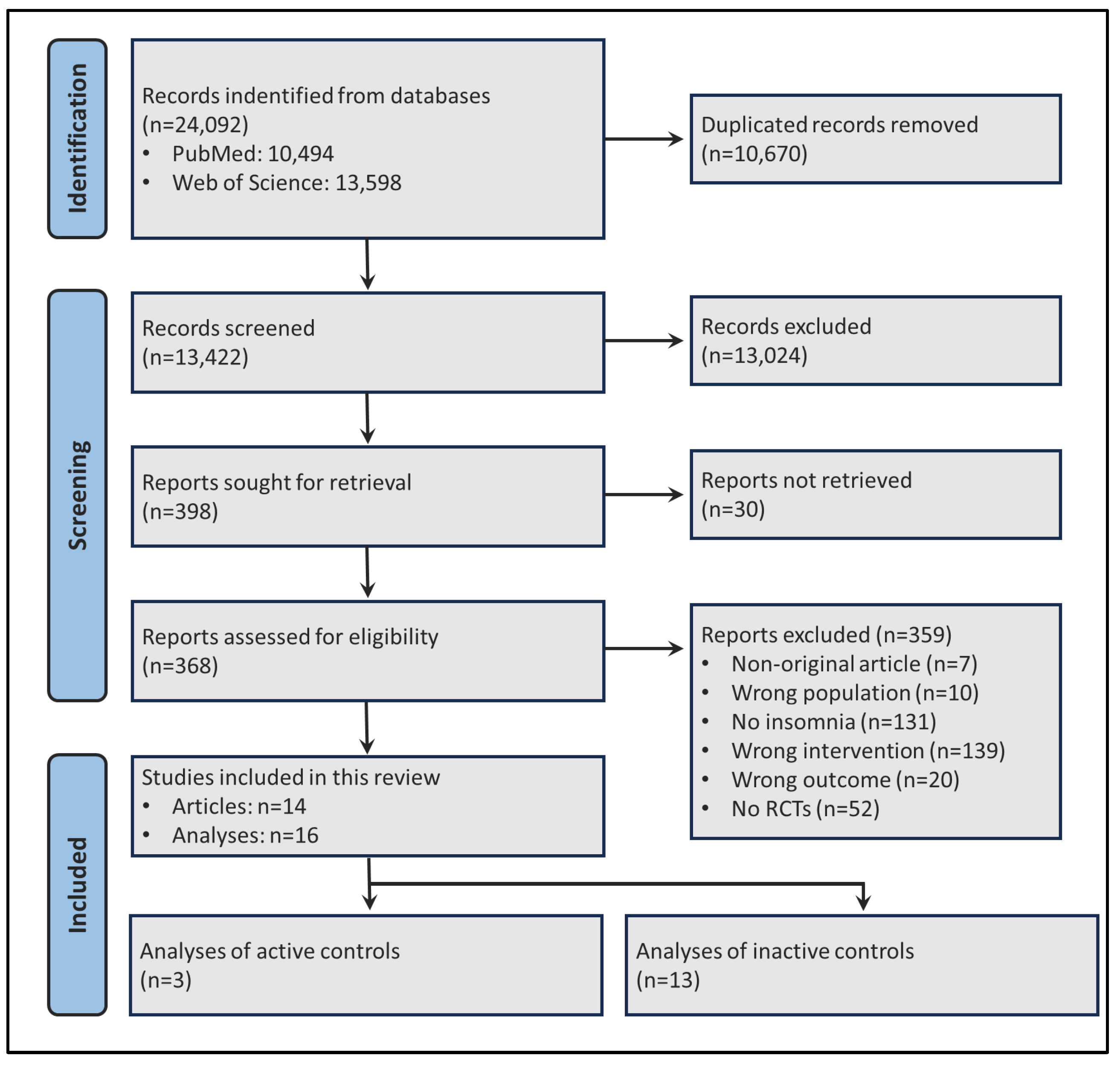

2.1. Search Strategy and Article Selection Process

- Abstract and Language: English or Portuguese.

- Article Type: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

- Population: Adults diagnosed with insomnia disorder based on the ICSD-3 (International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd edition), DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition), or equivalent guidelines. Adults with moderate to severe insomnia symptoms, as measured by the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) or the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS), were also included. Self-reported insomnia diagnosis, or symptoms evaluation including mild or subclinical insomnia were excluded.

- Intervention: CBT-I delivered through digital platforms (websites or smartphone applications) for at least 6 weeks.

- Control Group: Active (telehealth CBT-I, in-person CBT-I, or pharmacological treatment) or inactive (waiting list, no treatment, minimal intervention, or placebo) control groups.

- Outcomes: Sleep parameters (calculated from sleep diaries data or obtained through polysomnography).

2.2. Data Extraction

- Sleep parameters: TST, SOL, SE, WASO, and NWAK, in any measurement unit (most likely time or percentage).

- Data for each parameter: Extracted for both experimental and control groups, including the number of participants per group, means, and standard deviations. When data was reported in the median, standard error or 95% confidence intervals (95CI), the values were converted into mean and standard deviations following recommended Cochrane formulas.

- Intervention time: The total duration of the intervention until outcome measurement.

- App/site: The name of the application or website used to deliver dCBT-I.

- Comparator: Whether the control group was active or inactive, along with what was specifically used.

2.3. Data Synthesis and Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description and Qualitative Synthesis

3.2. Quantitative Synthesis

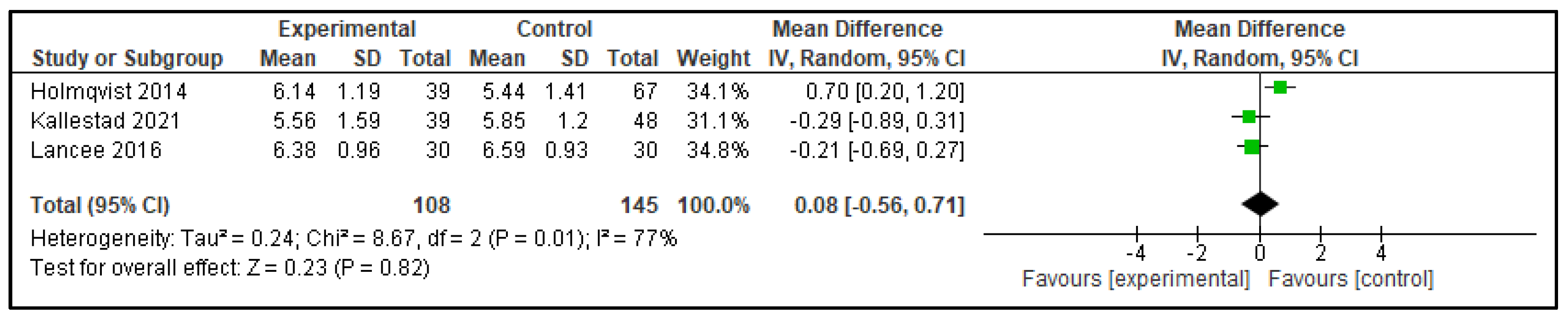

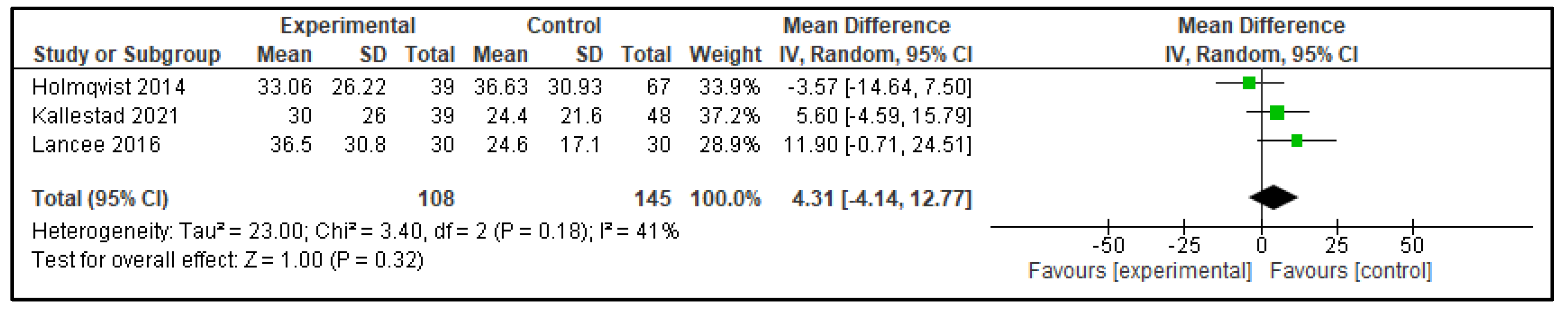

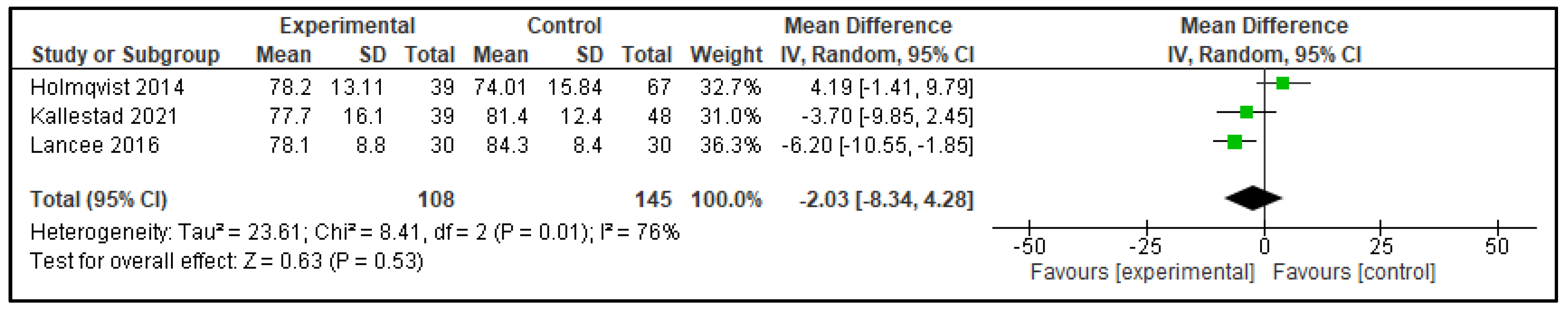

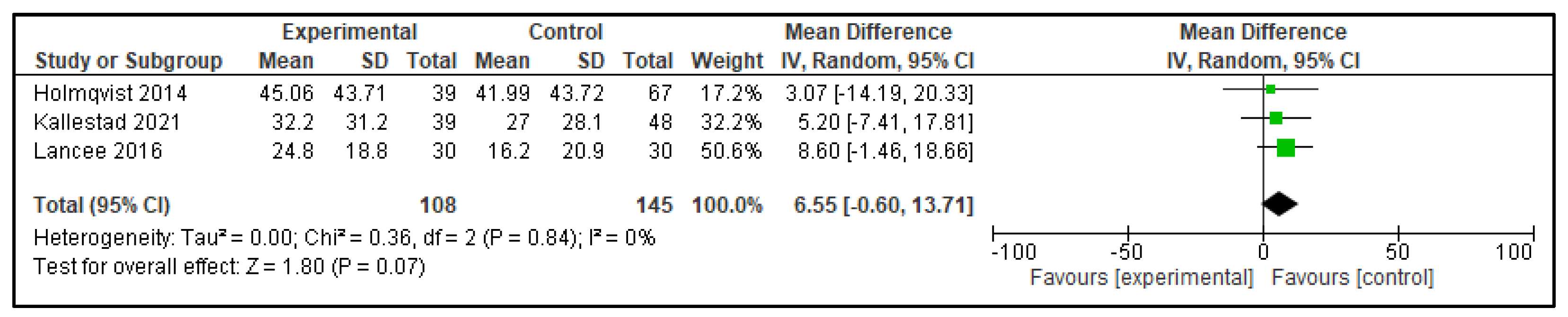

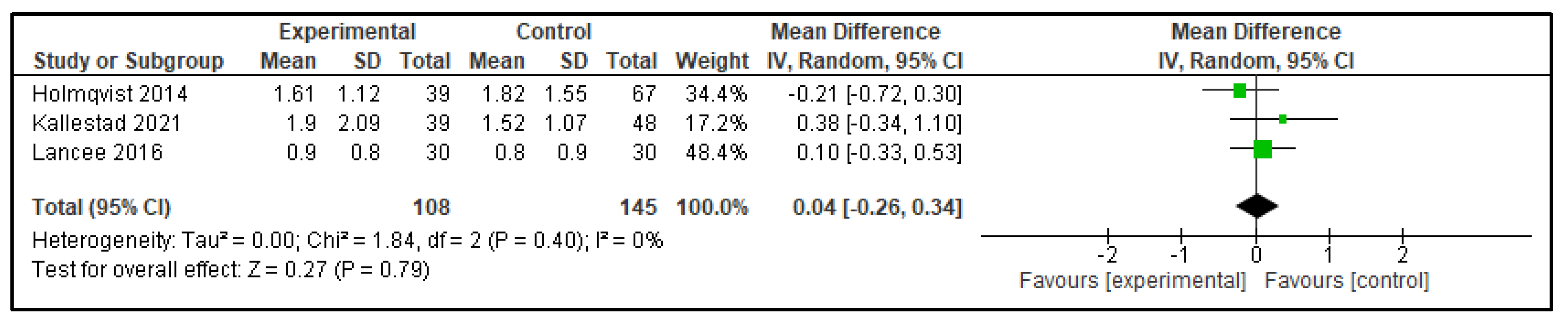

3.2.1. Digital CBT-I Versus Active Control Group

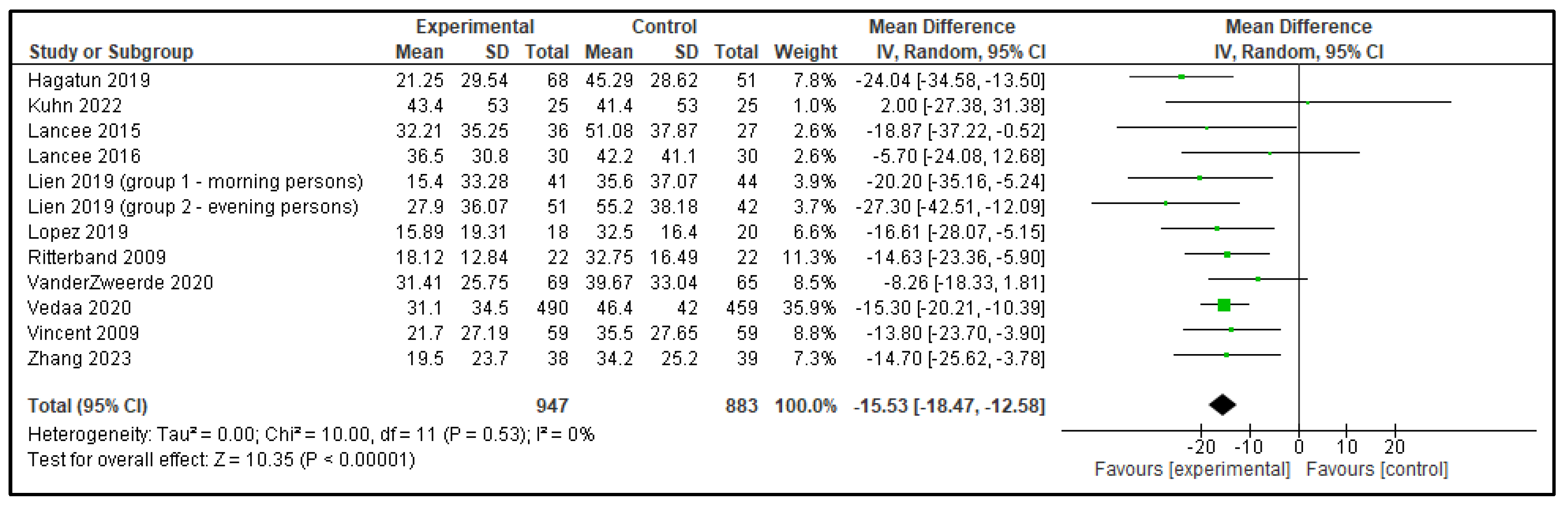

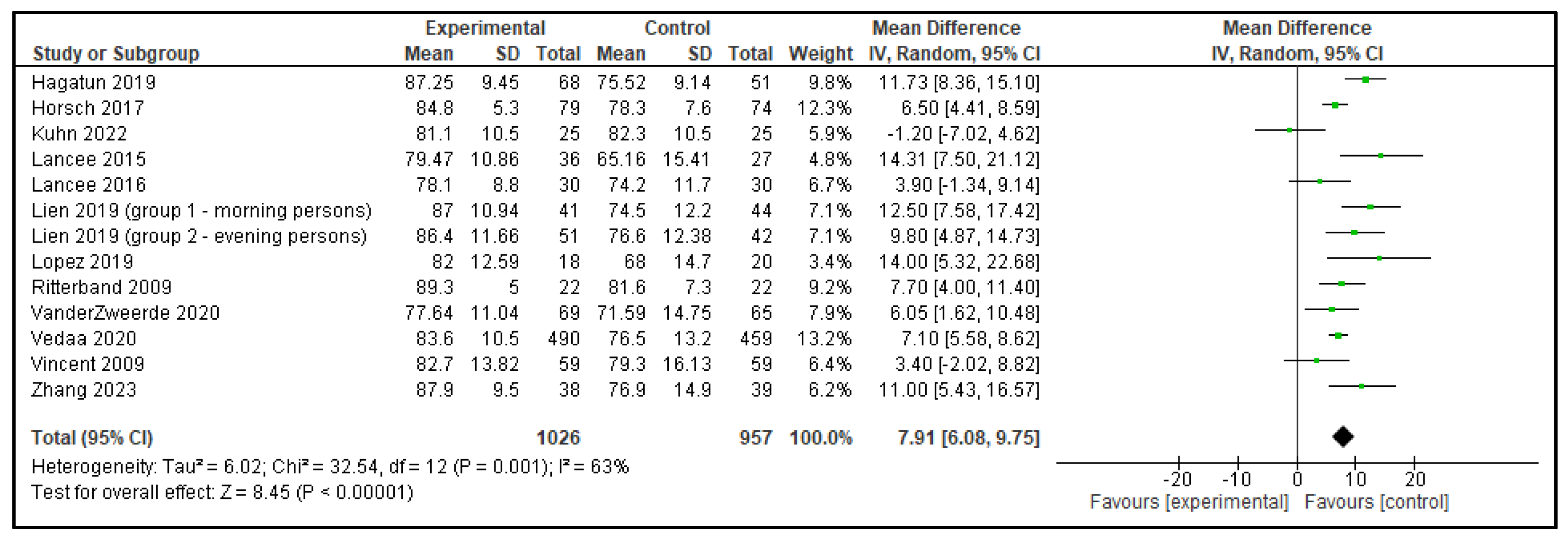

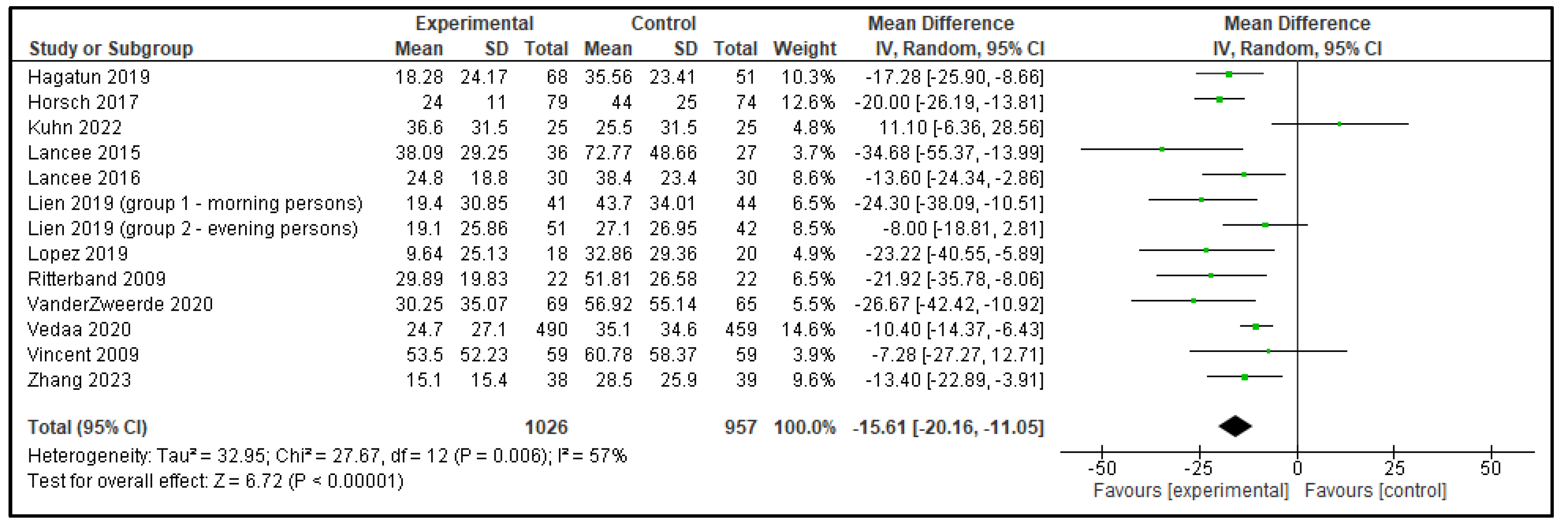

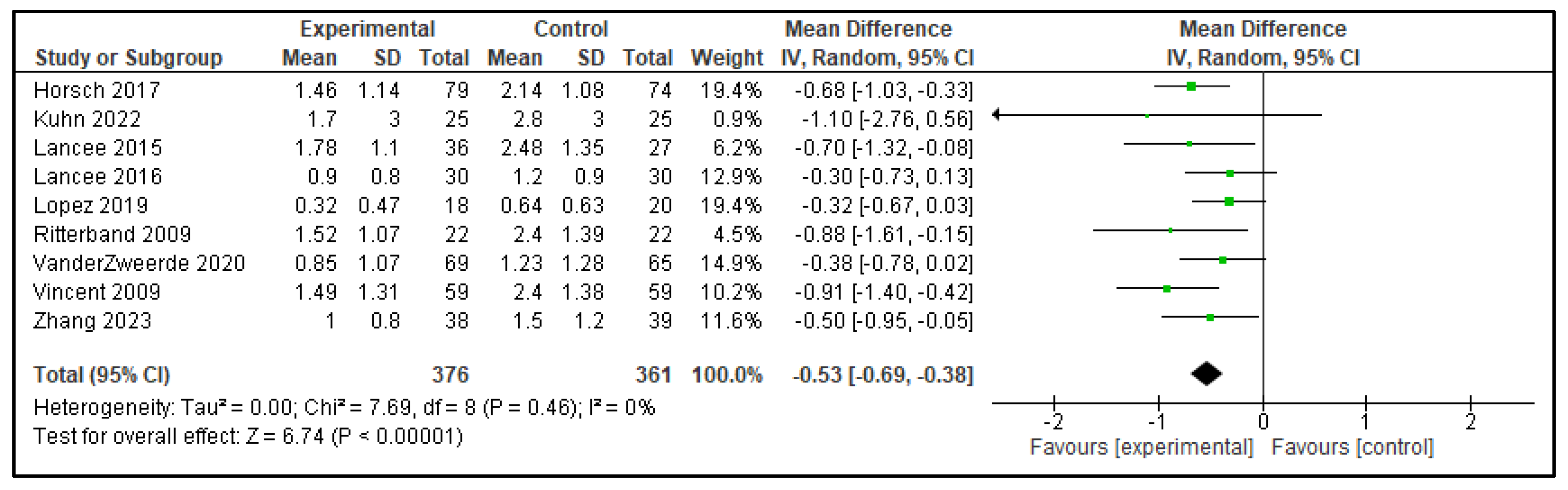

3.2.2. Digital CBT-I Versus Inactive Control Group

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBT-I | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia |

| DCBT-I | Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| PSG | Polysomnography |

| TST | Total Sleep Time |

| SOL | Sleep Onset Latency |

| SE | Sleep Efficiency |

| WASO | Wake After Sleep Onset |

| NWAK | Number of Awakenings |

| NFS | Not Further Specified |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2022; pp. 361–455. [Google Scholar]

- Drager, L.F.; Assis, M.; Bacelar, A.F.R.; Poyares, D.L.R.; Conway, S.G.; Pires, G.N.; de Azevedo, A.P.; Carissimi, A.; Eckeli, A.L.; Pentagna, Á.; et al. 2023 Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Insomnia in Adults-Brazilian Sleep Association. Sleep Sci. 2023, 16 (Suppl. 2), 507–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemann, D.; Espie, C.A.; Altena, E.; Arnardottir, E.S.; Baglioni, C.; Bassetti, C.L.A.; Bastien, C.; Berzina, N.; Bjorvatn, B.; Dikeos, D.; et al. The European Insomnia Guideline: An update on the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia 2023. J. Sleep Res. 2023, 32, e14035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.M.; Khullar, A.; Robillard, R.; Desautels, A.; Mak, M.S.B.; Dang-Vu, T.T.; Chow, W.; Habert, J.; Lessard, S.; Alima, L.; et al. Delphi consensus recommendations for the management of chronic insomnia in Canada. Sleep Med. 2024, 124, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edinger, J.D.; Arnedt, J.T.; Bertisch, S.M.; Carney, C.E.; Harrington, J.J.; Lichstein, K.L.; Sateia, M.M.J.; Troxel, W.M.; Zhou, E.S.; Kazmi, U.; et al. Behavioral and psychological treatments for chronic insomnia disorder in adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 17, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlis, M.L.; Posner, D.; Riemann, D.; Bastien, C.H.; Teel, J.; Thase, M. Insomnia. Lancet 2022, 400, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopheide, J.A. Insomnia overview: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and monitoring, and nonpharmacologic therapy. Am. J. Manag. Care 2020, 26 (Suppl. 4), S76–S84. [Google Scholar]

- Espie, C.A.; Emsley, R.; Kyle, S.D.; Gordon, C.; Drake, C.L.; Siriwardena, A.N.; Cape, J.; Ong, J.C.; Sheaves, B.; Foster, R.; et al. Effect of Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia on Health, Psychological Well-being, and Sleep-Related Quality of Life: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, H.L.; Ho, R.C.; Ho, C.S.; Tam, W.W. Efficacy of digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med. 2020, 75, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, F.; Tu, Y.K.; Yang, C.M.; James Gordon, C.; Wu, D.; Lee, H.C.; Yuliana, L.T.; Herawati, L.; Chen, T.-J.; Chiu, H.-Y. Comparative efficacy of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 61, 101567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H.; Holly, C.; Feyissa, G.; Godfrey, C.; Evans, C.; Sawchuck, D.; Sudhakar, M.; Asahngwa, C.; Stannard, D.; et al. Rapid reviews and the methodological rigor of evidence synthesis: A JBI position statement. JBI Evid. Synth. 2022, 20, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, A.; Hersi, M.; Garritty, C.; Hartling, L.; Shea, B.J.; Stewart, L.A.; Welch, V.A.; Tricco, A.C. Rapid review method series: Interim guidance for the reporting of rapid reviews. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2025, 30, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, H.J.; Yang, A.C.; Zhu, J.D.; Hsu, Y.Y.; Hsu, T.F.; Tsai, S.J. Effectiveness of Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia in Young People: Preliminary Findings from Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, M.; Bredeli, E.; Sivertsen, B.; Kallestad, H.; Pallesen, S.; Smith, O.R.F.; Faaland, P.; Ritterband, L.M.; Thorndike, F.P.; Vedaa, Ø. Short and long-term effects of unguided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia in morning and evening persons: A post-hoc analysis. Chronobiol. Int. 2019, 36, 1384–1398. [Google Scholar]

- Horsch, C.H.; Lancee, J.; Griffioen-Both, F.; Spruit, S.; Fitrianie, S.; Neerincx, M.A.; Beun, R.J.; Brinkman, W.-P. Mobile Phone-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia: A Randomized Waitlist Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e70. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zweerde, T.; Lancee, J.; Slottje, P.; Bosmans, J.E.; Van Someren, E.J.W.; van Straten, A. Nurse-Guided Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia in General Practice: Results from a Pragmatic Randomized Clinical Trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2020, 89, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Shen, Y.; Ma, J. Digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia using a smartphone application in China: A pilot randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e234866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagatun, S.; Vedaa, Ø.; Nordgreen, T.; Smith, O.R.F.; Pallesen, S.; Havik, O.E.; Bjorvatn, B.; Thorndike, F.P.; Ritterband, L.M.; Sivertsen, B. The Short-Term Efficacy of an Unguided Internet-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia: A Randomized Controlled Trial with a Six-Month Nonrandomized Follow-Up. Behav. Sleep Med. 2019, 17, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, E.; Miller, K.E.; Puran, D.; Wielgosz, J.; YorkWilliams, S.L.; Owen, J.E.; Jaworski, B.K.; Hallenbeck, H.W.; McCaslin, S.E.; Taylor, K.L. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of the Insomnia Coach Mobile App to Assess Its Feasibility, Acceptability, and Potential Efficacy. Behav. Ther. 2022, 53, 440–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancee, J.; Eisma, M.C.; van Straten, A.; Kamphuis, J.H. Sleep-Related Safety Behaviors and Dysfunctional Beliefs Mediate the Efficacy of Online CBT for Insomnia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2015, 44, 406–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, R.; Evangelista, E.; Barateau, L.; Chenini, S.; Bosco, A.; Billiard, M.; Bonte, A.-D.; Béziat, S.; Jaussent, I.; Dauvilliers, Y. French Language Online Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritterband, L.M.; Thorndike, F.P.; Gonder-Frederick, L.A.; Magee, J.C.; Bailey, E.T.; Saylor, D.K.; Morin, C.M. Efficacy of an Internet-based behavioral intervention for adults with insomnia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 692–698, Erratum in Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedaa, Ø.; Kallestad, H.; Scott, J.; Smith, O.R.F.; Pallesen, S.; Morken, G.; Langsrud, K.; Gehrman, P.; Thorndike, F.P.; Ritterband, L.M.; et al. Effects of digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia on insomnia severity: A large-scale randomised controlled trial. Lancet Digit. Health. 2020, 2, e397–e406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, N.; Lewycky, S. Logging on for better sleep: RCT of the effectiveness of online treatment for insomnia. Sleep 2009, 32, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancee, J.; van Straten, A.; Morina, N.; Kaldo, V.; Kamphuis, J.H. Guided Online or Face-to-Face Cognitive Behavioral Treatment for Insomnia: A Randomized Wait-List Controlled Trial. Sleep 2016, 39, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, M.; Vincent, N.; Walsh, K. Web- vs. telehealth-based delivery of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A randomized controlled trial. Sleep Med. 2014, 15, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallestad, H.; Scott, J.; Vedaa, Ø.; Lydersen, S.; Vethe, D.; Morken, G.; Stiles, T.C.; Sivertsen, B.; Langsrud, K. Mode of delivery of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia: A randomized controlled non-inferiority trial of digital and face-to-face therapy. Sleep 2021, 44, zsab185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ge, L.; Liu, M.; Niu, M.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J.; Yao, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of cognitive behavioral therapy delivery formats for insomnia in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 64, 101648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferini-Strambi, L. Insomnia disorder. Minerva Med. 2025, 116, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.A.; Gulliver, A.; Farrer, L.; Bennett, K.; Carron-Arthur, B. Internet interventions for mental health and addictions: Current findings and future directions. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, G.N.; Arnardóttir, E.S.; Bailly, S.; McNicholas, W.T. Guidelines for the development, performance evaluation and validation of new sleep technologies (DEVSleepTech guidelines)—A protocol for a Delphi consensus study. J. Sleep Res. 2024, 33, e14163. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Evidence Standards Framework for Digital Health Technologies; NICE: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/corporate/ecd7/resources/evidence-standards-framework-for-digital-health-technologies-pdf-1124017457605 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Kakazu, V.A.; Assis, M.; Bacelar, A.; Bezerra, A.G.; Ciutti, G.L.R.; Conway, S.G.; Galduróz, J.C.F.; Drager, L.F.; Khoury, M.P.; Leite, I.P.A.; et al. Insomnia and its treatments—Trend analysis and publication profile of randomized clinical trials. npj Biol. Timing Sleep 2024, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakazu, V.A.; Assis, M.; Bacelar, A.; Bezerra, A.G.; Ciutti, G.L.R.; Conway, S.G.; Galduróz, J.C.F.; Drager, L.F.; Khoury, M.P.; Leite, I.P.A.; et al. Industry sponsorship bias in randomized controlled trials of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A meta-research study based on the 2023 Brazilian guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia in adults. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1600767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espie, C.A.; Torous, J.; Brennan, T.A. Digital therapeutics should be regulated with gold-standard evidence. Health Affairs Forefront 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.S.; Poyares, D.; Leger, D.; Bittencourt, L.; Tufik, S. Objective prevalence of insomnia in the São Paulo, Brazil epidemiologic sleep study. Ann. Neurol. 2013, 74, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCall, C.; McCall, W.V. Comparison of actigraphy with polysomnography and sleep logs in depressed insomniacs. J. Sleep Res. 2012, 21, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espie, C.A.; Kyle, S.D.; Williams, C.; Ong, J.C.; Douglas, N.J.; Hames, P.; Brown, J.S. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep 2012, 35, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Analyses (n) | Program (App or Website) | Comparator | Control Type | Intervention Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lien 2019 [15] | 2 | SHUTi | Minimal intervention/sleep education | Inactive | 9 weeks |

| Horsch 2017 [16] | 1 | Sleepcare | No treatment/waiting list | Inactive | 6 weeks |

| Van der Zweerde 2020 [17] | 1 | i-Sleep | Care as usual/waiting list | Inactive | 5 weeks |

| Zhang 2023 [18] | 1 | Resleep | Minimal intervention/sleep education | Inactive | 6 weeks |

| Hagatun 2019 [19] | 1 | SHUTi | Minimal intervention/sleep education | Inactive | 6 months |

| Kuhn 2022 [20] | 1 | Insomnia Coach | No treatment/waiting list | Inactive | 6 weeks |

| Lancee 2015 [21] | 1 | Digital CBT-I protocol (NFS) | No treatment/waiting list | Inactive | 6 weeks |

| Lopez 2019 [22] | 1 | Digital CBT-I protocol (NFS) | Minimal intervention/sleep education | Inactive | 12 weeks |

| Ritterband 2009 [23] | 1 | SHUTi | No treatment/waiting list | Inactive | 9 weeks |

| Vedaa 2020 [24] | 1 | SHUTi | Minimal intervention/sleep education | Inactive | 9 weeks |

| Vincent 2009 [25] | 1 | Digital CBT-I protocol (NFS) | No treatment/waiting list | Inactive | 6 weeks |

| Lancee 2016 [26] | 2 | Digital CBT-I protocol (NFS) | No treatment/waiting list In-person CBT-I | Inactive Active | 6 weeks 6 weeks |

| Holmqvist 2014 [27] | 1 | Digital CBT-I protocol (NFS) | Telehealth and in-person CBT-I | Active | 6 weeks |

| Kallestad 2021 [28] | 1 | SHUTi | In-person CBT-I | Active | 6–9 weeks |

| Outcome | Active Control—Mean Difference (95% CI) | p | Inactive Control—Mean Difference (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TST | 0.08 (−0.56, 0.71) | p = 0.82 | 0.20 (0.11, 0.30) | p < 0.0001 |

| SOL | 4.31 (−4.14, 12.77) | p = 0.32 | −15.53 (−18.47, −12.58) | p < 0.00001 |

| SE | −2.03 (−8.34, 4.28) | p = 0.53 | 7.91 (6.08, 9.75) | p < 0.00001 |

| WASO | 6.55 (−0.60, 13.71) | p = 0.07 | −15.61 (−20.16, −11.05) | p < 0.00001 |

| NWAK | 0.04 (−0.26, 0.34) | p = 0.79 | −0.53 (−0.69, −0.38) | p < 0.00001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leite, I.P.A.; Kakazu, V.A.; de Carvalho, L.A.T.; Tufik, S.; Pires, G.N. Effects of Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia on Self-Reported Sleep Parameters: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clocks & Sleep 2025, 7, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7040069

Leite IPA, Kakazu VA, de Carvalho LAT, Tufik S, Pires GN. Effects of Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia on Self-Reported Sleep Parameters: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clocks & Sleep. 2025; 7(4):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7040069

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeite, Ingrid Porto Araújo, Viviane Akemi Kakazu, Lucca Andrade Teixeira de Carvalho, Sergio Tufik, and Gabriel Natan Pires. 2025. "Effects of Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia on Self-Reported Sleep Parameters: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Clocks & Sleep 7, no. 4: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7040069

APA StyleLeite, I. P. A., Kakazu, V. A., de Carvalho, L. A. T., Tufik, S., & Pires, G. N. (2025). Effects of Digital Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia on Self-Reported Sleep Parameters: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clocks & Sleep, 7(4), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep7040069