Acute Myocardial Infarction and Daylight Saving Time Transitions: Is There a Risk?

Abstract

1. Significance of the Phenomenon and Unanswered Questions—A Perspective

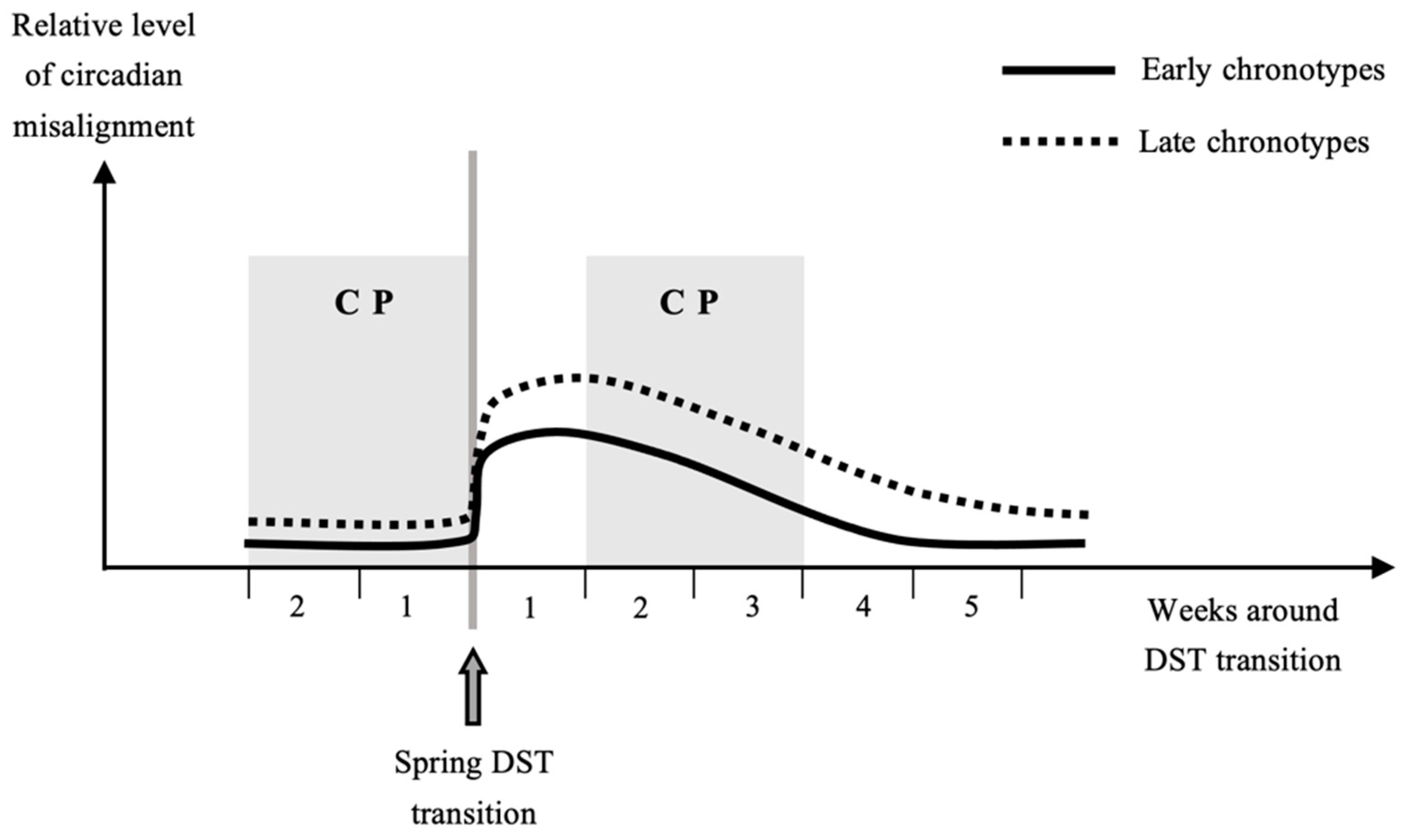

2. Circadian Clock, Chronotypes and DST

3. Previous Research: The Problem of Control Period in Spring

4. Interactions among Chronotypes, Sex and Geographical Locations

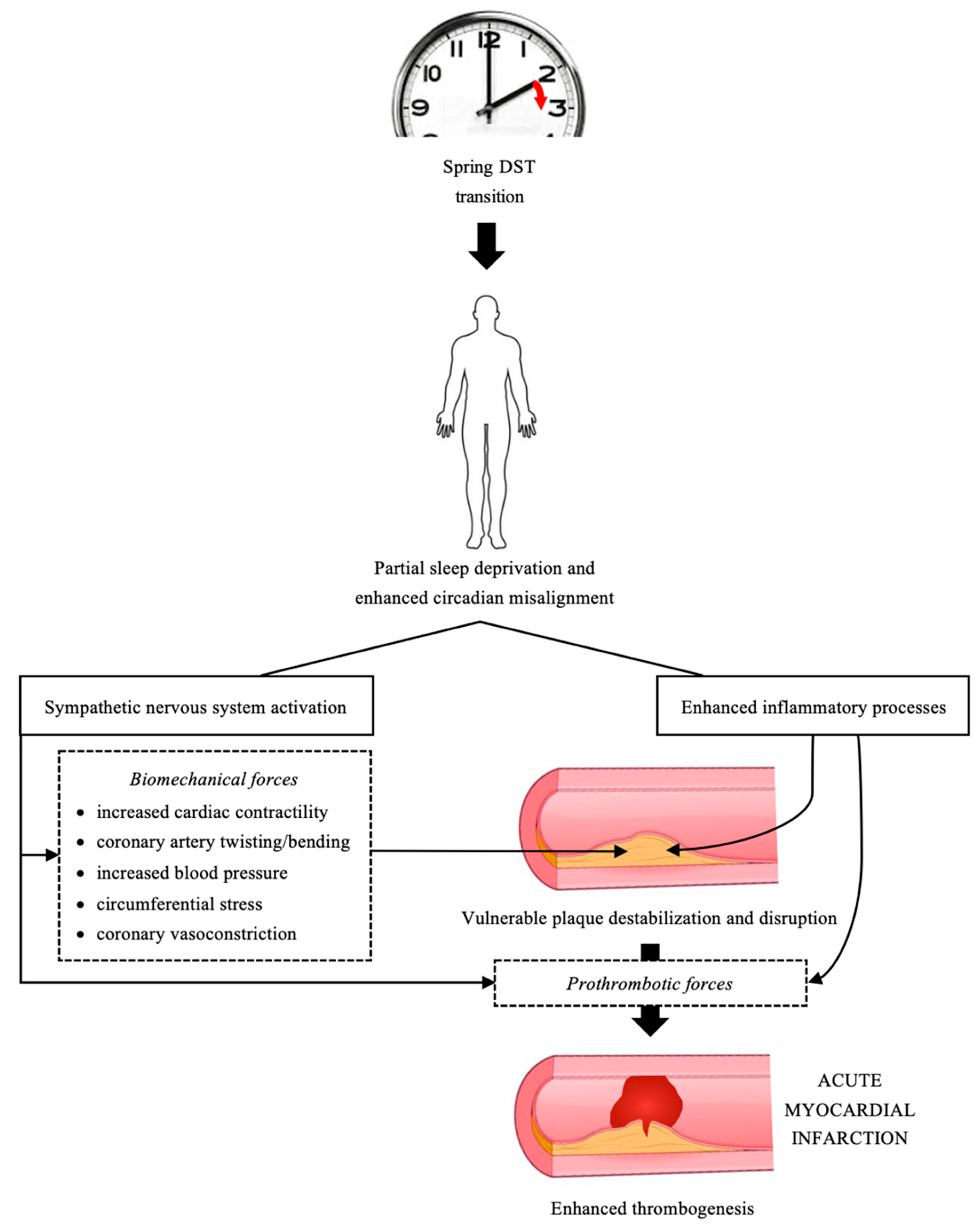

5. AMI and DST: Possible Underlying Pathophysiological Mechanisms

6. Possible Role of Cardiovascular Medication

7. Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crea, F.; Libby, P. Acute coronary syndromes: The way forward from mechanisms to precision treatment. Circulation 2017, 136, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čulić, V. Acute risk factors for myocardial infarction. Int. J. Cardiol. 2007, 117, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janszky, I.; Ljung, R. Shifts to and from daylight saving time and incidence of myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 1966–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiddou, M.R.; Pica, M.; Boura, J.; Qu, L.; Franklin, B.A. Incidence of myocardial infarction with shifts to and from daylight savings time. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 111, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čulić, V. Daylight saving time transitions and acute myocardial infarction. Chronobiol. Int. 2013, 30, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janszky, I.; Ahnve, S.; Ljung, R.; Mukamal, K.J.; Gautam, S.; Wallentin, L.; Stenestrand, U. Daylight saving time shifts and incidence of acute myocardial infarction—Swedish register of information and knowledge about swedish heart intensive care admissions (RIKS-HIA). Sleep Med. 2012, 13, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derks, L.; Houterman, S.; Geuzebroek, G.S.C.; van der Harst, P.; Smits, P.C.; PCI Registration Committee of the Netherlands Heart Registration. Daylight saving time does not seem to be associated with number of percutaneous coronary interventions for acute myocar-dial infarction in the Netherlands. Neth. Heart J. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchberger, I.; Wolf, K.; Heier, M.; Kuch, B.; von Scheidt, W.; Peters, A.; Meisinger, C. Are daylight saving time transitions associated with changes in myocardial infarction incidence? Results from the German MONICA/KORA myocardial infarction registry. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipilä, J.; Rautava, P.; Kytö, V. Association of daylight saving time transitions with incidence and in-hospital mortality of myocardial infarction in Finland. Ann. Med. 2015, 48, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredini, R.; Fabbian, F.; Cappadona, R.; De Giorgi, A.; Bravi, F.; Carradori, T.; Flacco, M.E.; Manzoli, L. Daylight saving time and acute myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg, T.; Wirz-Justice, A.; Merrow, M. Life between clocks: Daily temporal patterns of human chronotypes. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2003, 18, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantermann, T.; Eastman, C.I. Circadian phase, circadian period and chronotype are reproducible over months. Chronobiol. Int. 2018, 35, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantermann, T.; Sung, H.; Burgess, H.J. Comparing the morningness-eveningness questionnaire and munich chronotype questionnaire to the dim light melatonin onset. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2015, 30, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merikanto, I.; Lahti, T.; Puolijoki, H.; Vanhala, M.; Peltonen, M.; Laatikainen, T.; Vartiainen, E.; Salomaa, V.; Kronholm, E.; Partonen, T. Associations of chronotype and sleep with cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes. Chronobiol. Int. 2013, 30, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittmann, M.; Dinich, J.; Merrow, M.; Roenneberg, T. Social jetlag: Misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol. Int. 2006, 23, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutters, F.; Lemmens, S.G.; Adam, T.C.; Bremmer, M.A.; Elders, P.J.; Nijpels, G.; Dekker, J.M. Is social jetlag associated with an adverse endocrine, behavioral, and cardiovascular risk profile? J. Biol. Rhythm. 2014, 29, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantermann, T.; Duboutay, F.; Haubruge, D.; Kerkhofs, M.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A.; Skene, D.J. Atherosclerotic risk and social jetlag in rotating shift-workers: First evidence from a pilot study. Work 2013, 46, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantermann, T.; Juda, M.; Merrow, M.; Roenneberg, T. The human circadian clock’s seasonal adjustment is disrupted by daylight saving time. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 1996–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putilov, A.A.; Poluektov, M.G.; Dorokhov, V.B. Evening chronotype, late weekend sleep times and social jetlag as possible causes of sleep curtailment after maintaining perennial DST: Ain’t they as black as they are painted? Chronobiol. Int. 2020, 37, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basner, M.; Dinges, D.F. Sleep duration in the United States 2003–2016: First signs of success in the fight against sleep deficiency? Sleep 2018, 41, zsy012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa Madeira, S.; Reis, C.; Paiva, T.; Moreira, C.S.; Nogueira, P.; Roenneberg, T. Social jetlag, a novel predictor for high cardiovascular risk in blue-collar workers following permanent atypical work schedules. J. Sleep Res. 2021, e13380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Malik, B.H.; Gupta, D.; Rutkofsky, I. The role of circadian misalignment due to insomnia, lack of sleep, and shift work in increasing the risk of cardiac diseases: A systematic review. Cureus 2020, 12, e6616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, J.; Fang, Y.; Goldstein, C.; Forger, D.; Sen, S.; Burmeister, M. Genomic heterogeneity affects the response to daylight saving time. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roenneberg, T.; Kuehnle, T.; Pramstaller, P.P.; Ricken, J.; Havel, M.; Guth, A.; Merrow, M. A marker for the end of adolescence. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, R1038–R1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randler, C. Morningness-eveningness comparison in adolescents from different countries around the world. Chronobiol. Int. 2008, 25, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allada, R.; Bass, J. Circadian mechanisms in medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, M.R.; Opp, M.R. Sleep health: Reciprocal regulation of sleep and innate immunity. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 129–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobaldini, E.; Cogliati, C.; Fiorelli, E.M.; Nunziata, V.; Wu, M.A.; Prado, M.; Bevilacqua, M.; Trabattoni, D.; Porta, A.; Montano, N. One night on-call: Sleep deprivation affects cardiac autonomic control and inflammation in physicians. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 24, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier-Ewert, H.K.; Ridker, P.M.; Rifai, N.; Regan, M.M.; Price, N.J.; Dinges, D.F.; Mullington, J.M. Effect of sleep loss on C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker of cardiovascular risk. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 43, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettoni, J.L.; Consolim-Colombo, F.M.; Drager, L.F.; Rubira, M.C.; Souza, S.B.; Irigoyen, M.C.; Mostarda, C.; Borile, S.; Krieger, E.M.; Moreno, H., Jr.; et al. Cardiovascular effects of partial sleep deprivation in healthy volunteers. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 113, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Hilton, H.J.; Gates, G.J.; Jelic, S.; Stern, Y.; Bartels, M.N.; Demeersman, R.E.; Basner, R.C. Increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic cardiovascular modulation in normal humans with acute sleep deprivation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 98, 2024–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, M.R.; Ziegler, M. Sleep deprivation potentiates activation of cardiovascular and catecholamine responses in abstinent alcoholics. Hypertension 2005, 45, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kuetting, D.L.R.; Feisst, A.; Sprinkart, A.M.; Homsi, R.; Luetkens, J.; Thomas, D.; Schild, H.H.; Dabir, D. Effects of a 24-hr-shift-related short-term sleep deprivation on cardiac function: A cardiac magnetic resonance-based study. J. Sleep Res. 2019, 28, e12665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunbul, M.; Kanar, B.G.; Durmus, E.; Kivrak, T.; Sari, I. Acute sleep deprivation is associated with increased arterial stiffness in healthy young adults. Sleep Breath. 2014, 18, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, T.; Daimon, M.; Hasegawa, R.; Toyoda, T.; Kawata, T.; Funabashi, N.; Komuro, I. The impact of sleep deprivation on the coronary circulation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010, 144, 266–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvin, A.D.; Covassin, N.; Kremers, W.K.; Adachi, T.; Macedo, P.; Albuquerque, F.N.; Bukartyk, J.; Davison, D.E.; Levine, J.A.; Singh, P.; et al. Experimental sleep restriction causes endothelial dysfunction in healthy humans. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 2014, 3, e001143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, O.; Alroy, S.; Schliamser, J.E.; Asmir, I.; Shiran, A.; Flugelman, M.Y.; Halon, D.A.; Lewis, B.S. Brachial artery endothelial function in residents and fellows working night shifts. Am. J. Cardiol. 2004, 93, 947–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakao, T.; Yasumoto, A.; Tokuoka, S.; Kita, Y.; Kawahara, T.; Daimon, M.; Yatomi, Y. The impact of night-shift work on platelet function in healthy medical staff. J. Occup. Health. 2018, 60, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarem, N.; Paul, J.; Giardina, E.V.; Liao, M.; Aggarwal, B. Evening chronotype is associated with poor cardiovascular health and adverse health behaviors in a diverse population of women. Chronobiol. Int. 2020, 37, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hug, E.; Winzeler, K.; Pfaltz, M.C.; Cajochen, C.; Bader, K. Later chronotype is associated with higher alcohol consumption and more adverse childhood experiences in young healthy women. Clocks Sleep 2019, 1, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, F.; Malone, S.K.; Lozano, A.; Grandner, M.A.; Hanlon, A.L. Smoking, screen-based sedentary behavior, and diet associated with habitual sleep duration and chronotype: Data from the UK Biobank. Ann. Behav. Med. 2016, 50, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, A.J.; Fischer, U.; Mehta, Z.; Rothwell, P.M. Effects of antihypertensive-drug class on interindividual variation in blood pressure and risk of stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010, 375, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysant, S.G.; Chrysant, G.S.; Dimas, B. Current and future status of beta-blockers in the treatment of hypertension. Clin. Cardiol. 2008, 31, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparrini, A.; Armstrong, B. Reducing and meta-analysing estimates from distributed lag non-linear models. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touloumi, G.; Atkinson, R.; Tertre, A.L.; Samoli, E.; Schwartz, J.; Schindler, C.; Vonk, J.M.; Rossi, G.; Saez, M.; Rabszenko, D.; et al. Analysis of health outcome time series data in epidemiological studies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 15, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J.L.; Cummins, S.; Gasparrini, A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: A tutorial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabhajosyula, S.; Patlolla, S.H.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Holmes, D.R., Jr.; Gersh, B.J. Influence of seasons on the management and outcomes acute myocardial infarction: An 18-year US study. Clin. Cardiol. 2020, 43, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.; Keates, A.K.; Redfern, A.; McMurray, J.J.V. Seasonal variations in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg, T.; Kuehnle, T.; Juda, M.; Kantermann, T.; Allebrandt, K.; Gordijn, M.; Merrow, M. Epidemiology of the human circadian clock. Sleep Med. Rev. 2007, 6, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, J.A.; Östberg, O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int. J. Chronobiol. 1976, 2, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lewy, A.J. Melatonin as a marker and phase-resetter of circadian rhythms in humans. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1999, 460, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lewy, A.J.; Sack, R.L. The dim light melatonin onset as a marker for circadian phase position. Chronobiol. Int. 1989, 1, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benloucif, S.; Burgess, H.J.; Klerman, E.B.; Lewy, A.J.; Middleton, B.; Murphy, P.J.; Parry, B.L.; Revell, V.L. Measuring melatonin in humans. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2008, 1, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenbrink, N.; Ananthasubramaniam, B.; Münch, M.; Koller, B.; Maier, B.; Weschke, C.; Bes, F.; de Zeeuw, J.; Nowozin, C.; Wahnschaffe, A.; et al. High-accuracy determination of internal circadian time from a single blood sample. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3826–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čulić, V. Daylight saving time and myocardial infarction in Finland. Ann. Med. 2016, 48, 169–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dahlén, T.; Khan, A.; Edgren, G.; Rzhetsky, A. Measurable health effects associated with the daylight saving time shift. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meira, E.C.M.; Miyazawa, M.; Manfredini, R.; Cardinali, D.; Madrid, J.A.; Reiter, R.; Araujo, J.F.; Agostinho, R.; Acuña-Castroviejo, D. Impact of daylight saving time on circadian timing system: An expert statement. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 60, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study [Reference Number] | Incidence Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) of AMI (Post-Transitional Week vs. Control Weeks) | |

|---|---|---|

| Spring (to DST) | Autumn (from DST) | |

| Janszky and Ljung, 2008 [3] | 1.051 (1.032–1.071) | 0.985 (0.969–1.002) |

| Janszky et al., 2012 [6] | 1.039 (1.003–1.075) | 0.995 (0.965–1.026) |

| Čulić, 2013 [5] | 1.15 (1.04–1.26) | 1.19 (1.07–1.32) |

| Jiddou et al., 2013 [4] | 1.17 (1.00–1.36) | 0.99 (0.85–1.16) |

| Kirchberger et al., 2015 [8] | 1.077 (0.981–1.182) | 1.025 (0.928–1.133) |

| Sipilä et al., 2015 [9] | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) |

| Derks et al., 2021 [7] | 0.99 (0.94–1.05) | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Čulić, V.; Kantermann, T. Acute Myocardial Infarction and Daylight Saving Time Transitions: Is There a Risk? Clocks & Sleep 2021, 3, 547-557. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep3040039

Čulić V, Kantermann T. Acute Myocardial Infarction and Daylight Saving Time Transitions: Is There a Risk? Clocks & Sleep. 2021; 3(4):547-557. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep3040039

Chicago/Turabian StyleČulić, Viktor, and Thomas Kantermann. 2021. "Acute Myocardial Infarction and Daylight Saving Time Transitions: Is There a Risk?" Clocks & Sleep 3, no. 4: 547-557. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep3040039

APA StyleČulić, V., & Kantermann, T. (2021). Acute Myocardial Infarction and Daylight Saving Time Transitions: Is There a Risk? Clocks & Sleep, 3(4), 547-557. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep3040039