The Tarnishing of Silver in Museum Collections: A Study at the National Archaeological Museum (Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Display Cases

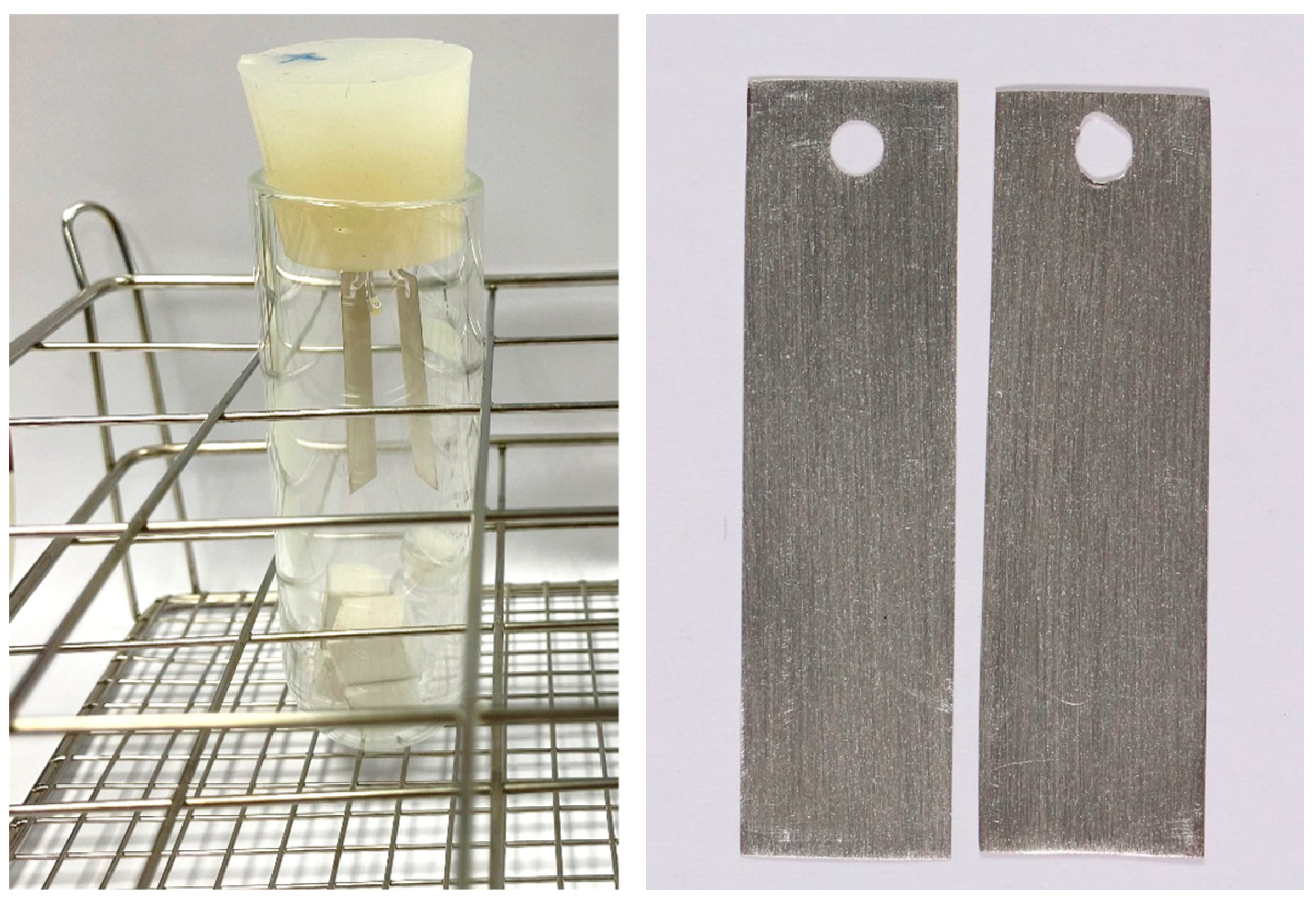

2.2. Preparation and Exposure of Silver Coupons

2.3. Monitoring of Environmental Conditions

2.4. Color Measurements

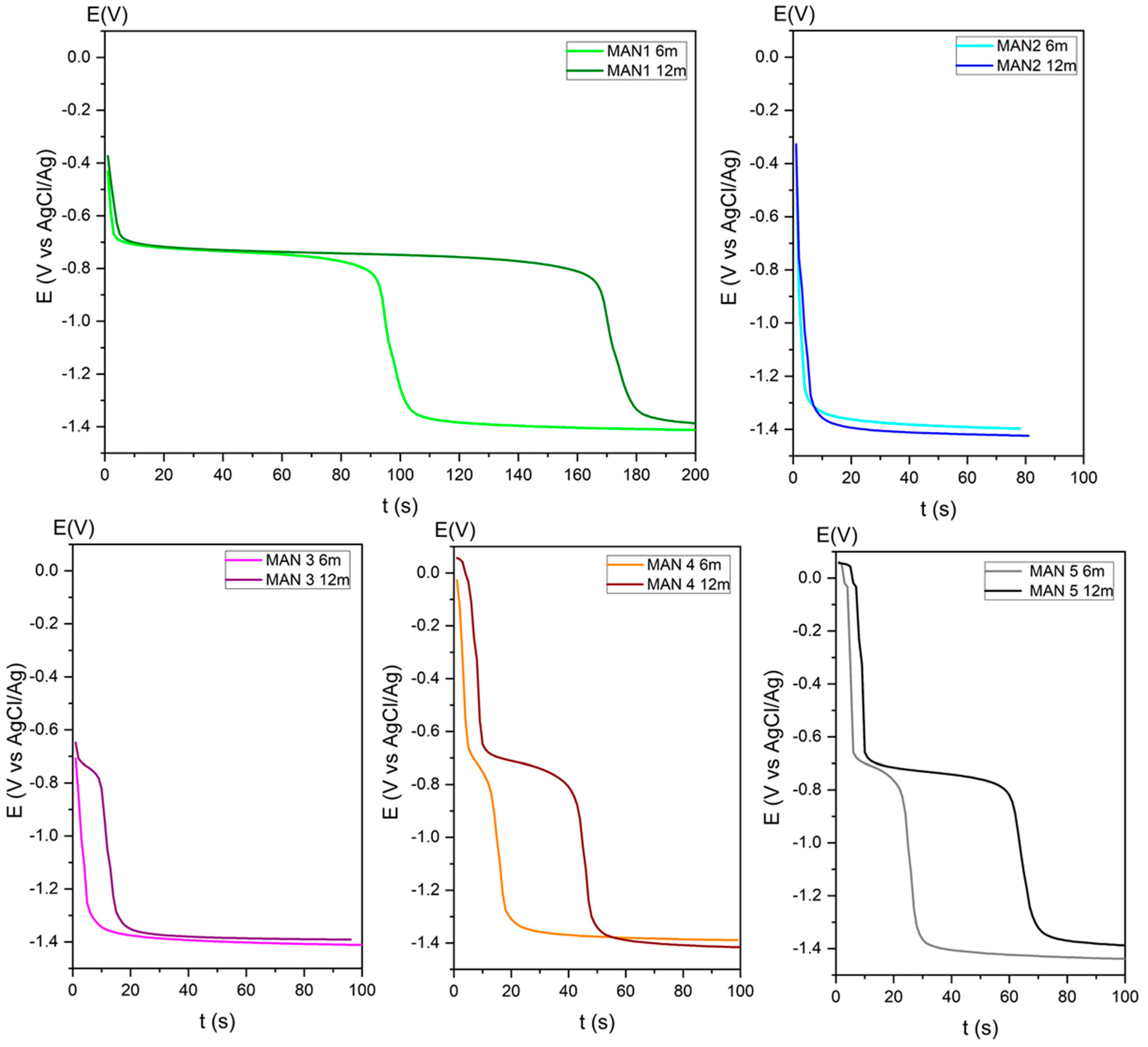

2.5. Determination of the Corrosion Rate

2.6. Identification of Corrosion Products

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Conditions

3.2. Tarnishing of Silver Coupons After Exposure

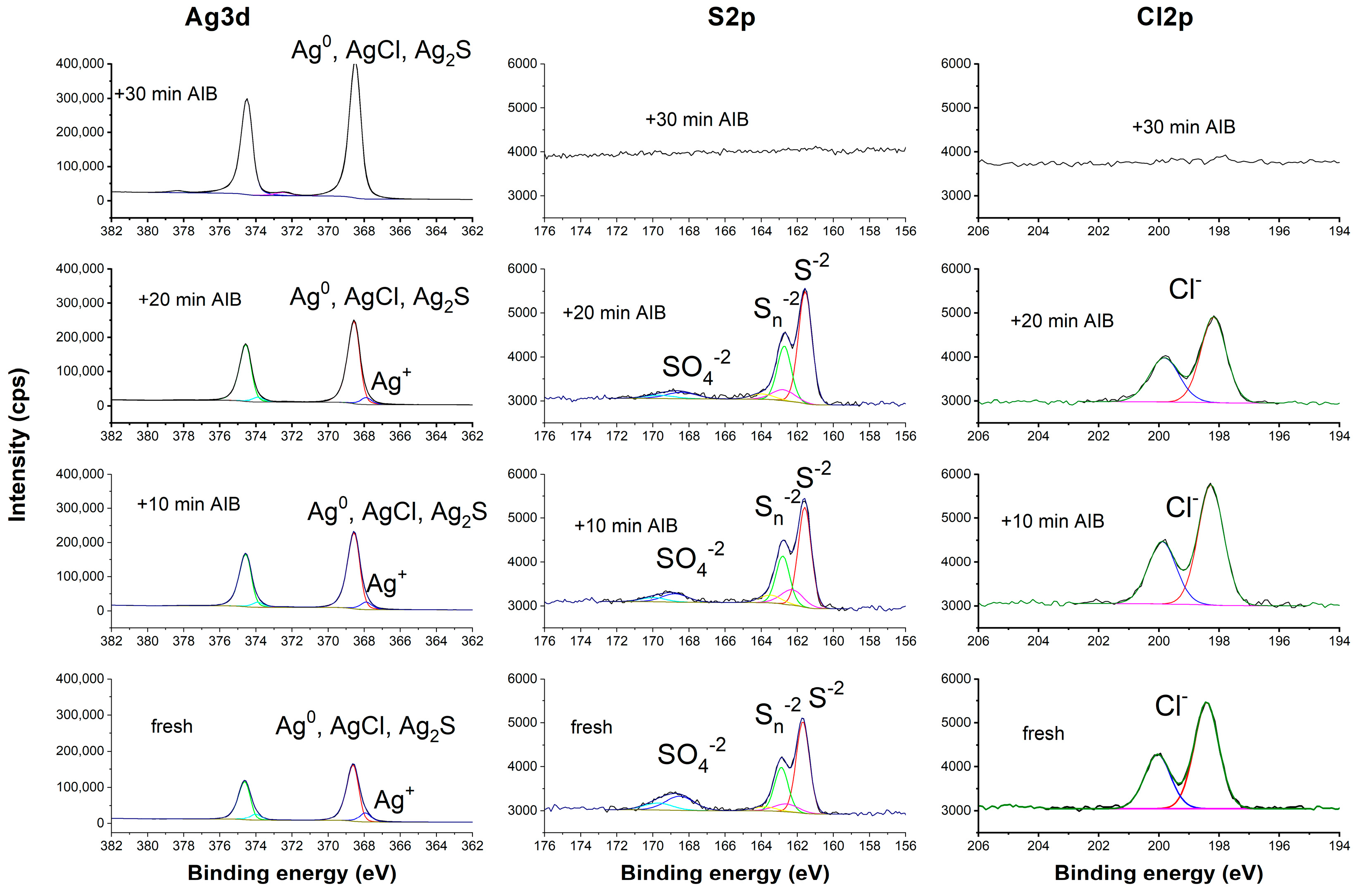

3.3. Identification of Corrosion Products

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T | Temperature |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| XPS | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compounds |

Appendix A

References

- Palomar, T.; Ramírez Barat, B.; García, E.; Cano, E. A Comparative Study of Cleaning Methods for Tarnished Silver. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 17, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graedel, T.E. Corrosion Mechanisms for Silver Exposed to the Atmosphere. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1992, 139, 1963–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V. The Deterioration of Silver Alloys and Some Aspects of Their Conservation. Stud. Conserv. 2001, 46, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, K.; Thickett, D.; McPhail, D.S.; Chater, R.J. Application of SIMS to Silver Tarnish at the British Museum. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2003, 203–204, 789–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thickett, D.; Hallett, K. Managing Silver Tarnish. In Proceedings of the ICOM-CC 19th Triennial Conference Preprints, Beijing, China, 17–21 May 2021; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 11844-2:2020; Corrosion of Metals and Alloys—Classification of Low Corrosivity of Indoor Atmospheres—Part 2: Determination of Corrosion Attack in Indoor Atmospheres. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/73254.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Díaz, I.; Cano, E. Quantitative Oddy Test by the Incorporation of the Methodology of the ISO 11844 Standard: A Proof of Concept. J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 57, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, R.L.; Dignard, C.; Selwyn, L. Caring for Metal Objects. In Preventive Conservation Guidelines for Collections; Canadian Conservation Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tétreault, J. Control of Pollutants in Museums and Archives. Can. Conserv. Inst. Tech. Bull. 2021, 37, 1–82. [Google Scholar]

- Tétreault, J. The Evolution of Specifications for Limiting Pollutants in Museums and Archives. J. Can. Assoc. Conserv. 2018, 43, 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sivaguru, P.; Bi, X. Introduction to Silver Chemistry. In Silver Catalysis in Organic Synthesis; Li, C.-J., Bi, X., Eds.; Wiley-VCHVerlag GmbH& Co.: Weinheim, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Vanýsek, P. Electrochemical Series. In CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics; Lide, D.R., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1989; pp. 8–23. [Google Scholar]

- Reference Electrode Conversion Calculator|Pine Research Instrumentation. Available online: https://pineresearch.com/tools/reference-electrode-conversion-calculator/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- ISO 11844-1:2020; Corrosion of Metals and Alloys—Classification of Low Corrosivity of Indoor Atmospheres—Part 1: Determination and Estimation of Indoor Corrosivity. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Gao, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, B.; Li, J.; Mao, J.; Guo, J. Multifunctional Fabrics Embedded with Polypyrrole-Silver/Silver Chloride Nanocomposites for Solar-Driven Steam Generation and Photocatalytic Decontamination. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 323, 124477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantauzzi, M.; Elsener, B.; Atzei, D.; Rigoldi, A.; Rossi, A. Exploiting XPS for the Identification of Sulfides and Polysulfides. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 75953–75963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, C.M. Monitoring for Gaseous Pollutants in Museum Environments; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-89236-851-8. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda, Y.; Fukushima, T.; Sulaiman, A.; Musalam, I.; Yap, L.C.; Chotimongkol, L.; Judabong, S.; Potjanart, A.; Keowkangwal, O.; Yoshihara, K.; et al. Indoor Corrosion of Copper and Silver Exposed in Japan and ASEAN Countries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1991, 138, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, C.E.; Verreault, D.; Frankel, G.S.; Allen, H.C. The Role of Sulfur in the Atmospheric Corrosion of Silver. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, C630–C637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimblecombe, P.; Shooter, D.; Kaur, A. Wool and Reduced Sulphur Gases in Museum Air. Stud. Conserv. 1992, 37, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samide, M.J.; Smith, G.D. Assessing the Suitability of Unplasticized Poly(Vinyl Chloride) for Museum Showcase Construction. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 2022, 61, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddy Test. Available online: https://www.conservation-wiki.com/wiki/Oddy_Test (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Canosa, E.; Wiman, A.; Norrehed, S.; Hacke, M. Characterization of Emissions from Display Case Materials; Technical Report 2019; Riksantikvarieämbetet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Barat, B.; Cano, E.; Molina, M.T.; Barbero-Álvarez, M.A.; Rodrigo, J.A.; Menéndez, J.M. Design and Validation of Tailored Colour Reference Charts for Monitoring Cultural Heritage Degradation. npj Herit. Sci. 2021, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benigno, S.C.; Silvia, S.G.; Canela, M.C. Análisis del Ambiente Interior de Vitrinas en el Museo Arqueológico Nacional; CIEMAT: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pok, Š.; Kralj Cigić, I.; Strlič, M.; Rijavec, T. Poly(Vinyl Chloride) Degradation: Identification of Acidic Degradation Products, Their Emission Rates, and Implications for Heritage Collections. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Ortúzar, M.; Diaz Ocaña, I.; Molina Delgado, M.T.; Ramírez Barat, B. Productos de Limpieza En Museos: Evaluación de Su Idoneidad Para Objetos de Plata. Ge-Conservacion 2025, 28, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Case ID | Materials | Objects | Dimensions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAN 1 | 14.8 | Galvanized steel, anodized aluminum, and glass. Plinths and modules: Foamed PVC (Simopor®) | Painted ceramic, clay, silver, bronze, gold, and iron | 450 × 190 × 160 cm (13.68 m3) |  |

| MAN 2 | 13.4 | Painted ceramic, silver, and bronze | 364 × 190 × 80 cm (5.53 m3) |  | |

| MAN 3 | 11.9 | Silver and bronze | 270 × 190 × 80 cm (4.1 m3) |  | |

| MAN 4 | 10.1 | Galvanized steel, baked enamel aluminum sheet, and glass. Plinths and modules: Foamed PVC (Simopor®) | Painted ceramic, gold, silver, bronze, iron, lead, and stone | 590 × 230 × 100 cm (13.57 m3) |  |

| MAN 5 | Gallery 11 | Marble floors and plaster walls | - | 337 m2 |  |

| Location | Pollutant Level | Environmental Conditions | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO2 µg/m3 | HCOOH µg/m3 | CH3COOH µg/m3 | HCl µg/m3 | H2S µg/m3 | T (°C) avg. | T (°C) max | T (°C) min | RH avg. | RH max | RH min | Time RH ≥ 35% | |

| MAN 1 | 0.20 | 44 | <2.0 * | <0.2 * | >7.5 ** | 22.0 | 24.5 | 19 | 35.5 | 39.5 | 31 | 67% |

| MAN 2 | 0.32 | 36 | <2.0 * | <0.2 * | >7.5 ** | 21.6 | 23.5 | 19 | 35.6 | 39.5 | 33 | 77% |

| MAN 3 | 1.5 | 33 | <2.0 * | <0.2 * | >7.5 ** | 21.7 | 24 | 19 | 35.4 | 39 | 33 | 69% |

| MAN 4 | 0.45 | 12 | <2.0 * | <0.2 * | 3.3 | 22.1 | 24 | 20.0 | 35.4 | 42 | 21.5 | 62% |

| MAN 5 | 0.42 | 7.0 | <2.0 * | <0.2 * | 3.3 | 21.9 | 24 | 19.5 | 34.9 | 44 | 20.5 | 58% |

| ΔL* | Δa* | Δb* | ΔE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 m | 12 m | 6 m | 12 m | 6 m | 12 m | 6 m | 12 m | |

| MAN 1 | −28.71 | −52.8 | 19.8 | 23.44 | 41.02 | 8.57 | 53.84 | 58.40 |

| MAN 2 | −1.73 | −4.06 | 0.08 | 0.69 | 1.4 | 1.87 | 2.23 | 4.52 |

| MAN 3 | −3.72 | −4.27 | 0.14 | 0.47 | 1.38 | 5.14 | 3.97 | 6.70 |

| MAN 4 | −5.6 | −7.37 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 4.41 | 16.42 | 7.13 | 18.00 |

| MAN 5 | −7.91 | −17.63 | 0.83 | 5.31 | 7.49 | 27.03 | 10.93 | 32.71 |

| Coupon | Δm (6 m)/mg | Coupon | Δm (12 m)/mg |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAN1-6m-1 | 0.026 | MAN1-12m-1 | 0.041 |

| MAN1-6m-2 | 0.020 | MAN1-12m-2 | 0.036 |

| MAN1-6m-3 | - | MAN1-12m-3 | - |

| MAN2-6m-1 | 0.002 | MAN2-12m-1 | 0.002 |

| MAN2-6m-2 | 0.004 | MAN2-12m-2 | 0.002 |

| MAN2-6m-3 | 0.005 | MAN2-12m-3 | 0.000 |

| MAN3-6m-1 | −0.001 | MAN3-12m-1 | 0.000 |

| MAN3-6m-2 | −0.001 | MAN3-12m-2 | 0.002 |

| MAN3-6m-3 | 0.002 | MAN3-12m-3 | 0.000 |

| MAN4-6m-1 | 0.008 | MAN4-12m-1 | 0.014 |

| MAN4-6m-2 | 0.006 | MAN4-12m-2 | 0.013 |

| MAN4-6m-3 | 0.008 | MAN4-12m-3 | 0.010 |

| MAN5-6m-1 | 0.016 | MAN5-12m-1 | 0.033 |

| MAN5-6m-2 | 0.021 | MAN5-12m-2 | 0.028 |

| MAN5-6m-3 | 0.011 | MAN5-12m-3 | 0.020 |

| Reaction | Eº/V | Ag/AgCl (3M KCl) |

|---|---|---|

| Ag2SO4 + 2e− ⇆ 2 Ag + SO42− | 0.654 | 0.446 |

| 2 AgO + H2O + 2e− ⇆ Ag2O + 2OH− | 0.607 | 0.399 |

| Ag2O + H2O + 2e− ⇆ 2Ag + 2OH− | 0.342 | 0.134 |

| AgCl + e− ⇆ Ag + Cl− | 0.22233 | 0.014 |

| Ag2S + 2e− ⇆ 2 Ag + S2− | −0.691 | −0.899 |

| Reduction (mg Ag) | Gravimetry (Mass Gain, mg) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Vcorr (mg/m2 Year) | Category | Vcorr (mg/m2 Year) | Category |

| MAN1 (14.8) | 274.73 | IC 2 | 46.40 | IC 2 |

| MAN2 (13.4) | 9.60 | IC 1 | 4.91 | IC 1 |

| MAN3 (11.10) | 11.82 | IC 1 | 1.00 | IC 1 |

| MAN4 (10.1) | 57.36 | IC 1 | 14.83 | IC 1 |

| MAN5 (Gallery) | 76.35 | IC 1 | 29.04 | IC 1 |

| % at Element | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | O | C | Ag | Cl | S |

| Fresh | 11.7 | 35.17 | 39.4 | 5.4 | 8.4 |

| 10 min AIB (3000 eV) | 6.3 | 13.2 | 63.2 | 7.3 | 10.1 |

| 20 min AIB (+10 min 3000 eV) | 4.6 | 9.4 | 69.4 | 5.5 | 11.1 |

| 30 min AIB (+10 min 5000 eV) | 1.1 | 2.4 | 96.5 | nd | nd |

| % at Component | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Ag(0)/Ag2S/AgCl | Ag+ | Cl− | S2− | Sn− | SO42− |

| Fresh | 33.89 | 5.35 | 5.4 | 5.62 | 0.9 | 1.88 |

| 10 min AIB (3000 eV) | 57.4 | 5.32 | 7.3 | 7.06 | 1.16 | 1.85 |

| 20 min AIB (+10 min 3000 eV) | 63.95 | 4.91 | 5.5 | 8.57 | 1.4 | 1.13 |

| 30 min AIB (+10 min 5000 eV) | 96.3 | 0 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ramírez Barat, B.; Llorente, I.; Ruiz Zamora, E.; Molina, M.T.; Cano, E.; Culubret Worms, B.; García-Patrón, N. The Tarnishing of Silver in Museum Collections: A Study at the National Archaeological Museum (Spain). Heritage 2026, 9, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage9010011

Ramírez Barat B, Llorente I, Ruiz Zamora E, Molina MT, Cano E, Culubret Worms B, García-Patrón N. The Tarnishing of Silver in Museum Collections: A Study at the National Archaeological Museum (Spain). Heritage. 2026; 9(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage9010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamírez Barat, Blanca, Irene Llorente, Elena Ruiz Zamora, María Teresa Molina, Emilio Cano, Bárbara Culubret Worms, and Nayra García-Patrón. 2026. "The Tarnishing of Silver in Museum Collections: A Study at the National Archaeological Museum (Spain)" Heritage 9, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage9010011

APA StyleRamírez Barat, B., Llorente, I., Ruiz Zamora, E., Molina, M. T., Cano, E., Culubret Worms, B., & García-Patrón, N. (2026). The Tarnishing of Silver in Museum Collections: A Study at the National Archaeological Museum (Spain). Heritage, 9(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage9010011