The Papacy as Intangible Cultural Heritage

Abstract

1. Introduction

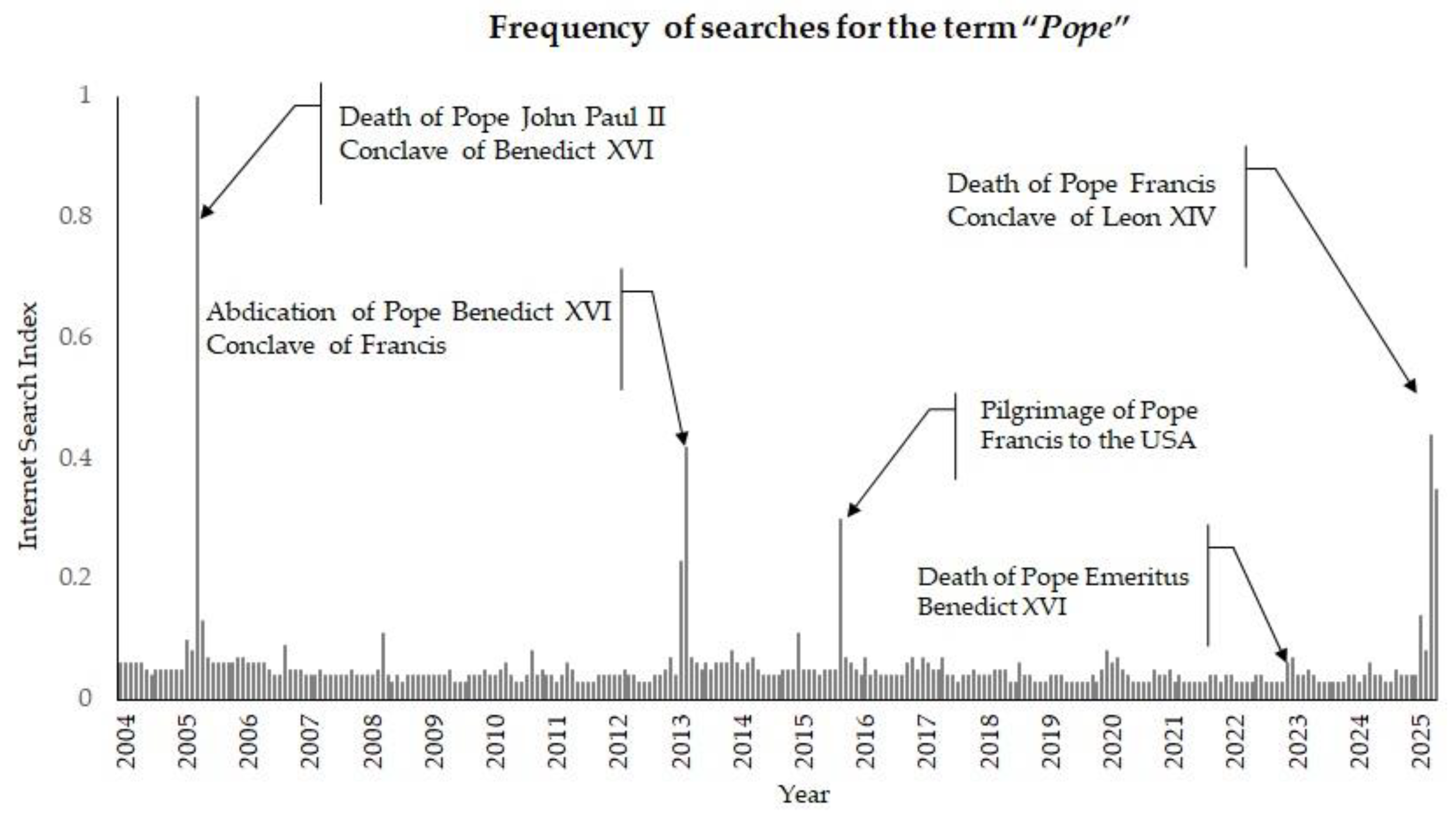

2. Materials and Methods

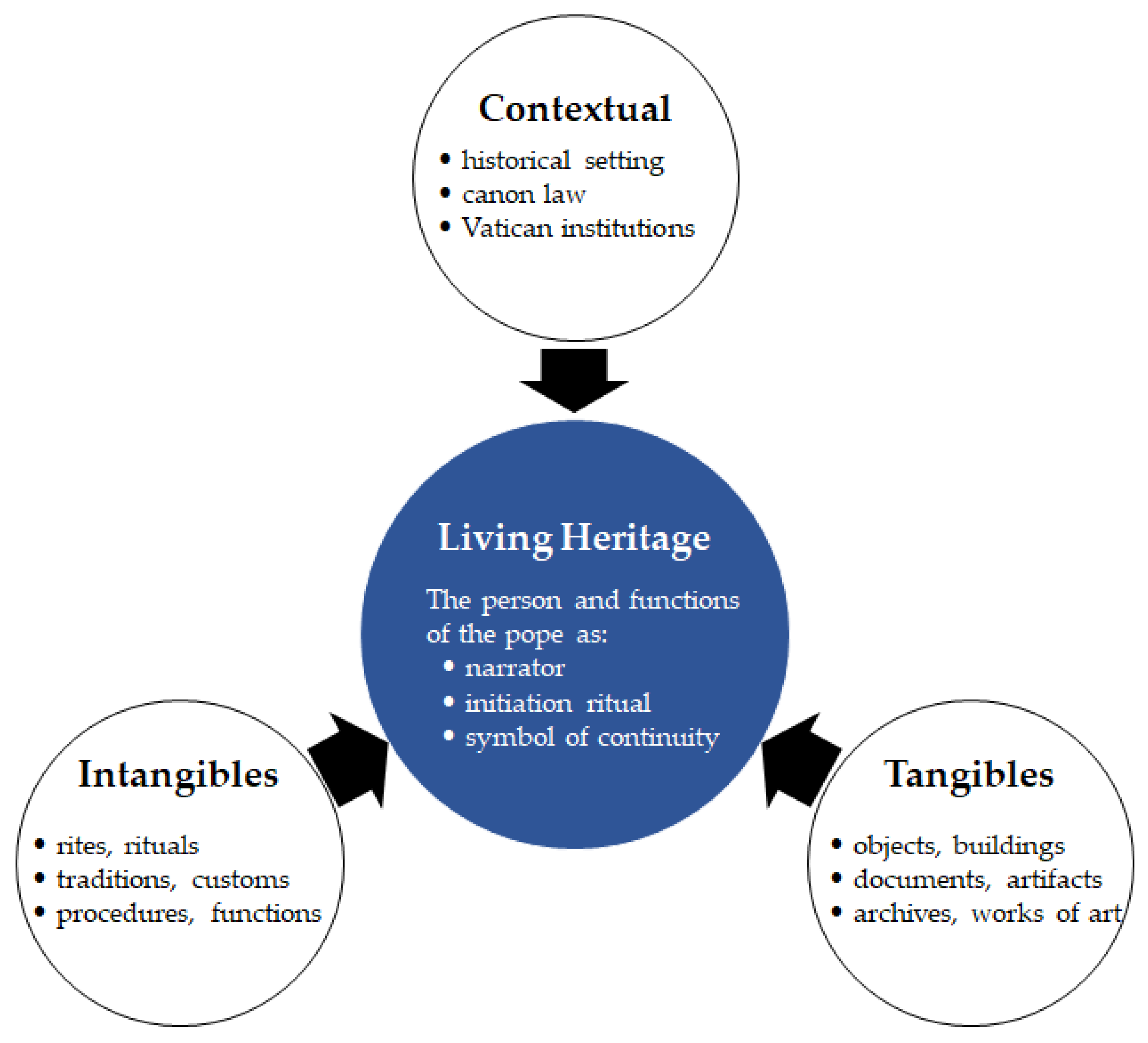

3. Pontifical Cultural Heritage

3.1. Religious Cultural Heritage

3.1.1. Tangible and Intangible Religious Heritage

3.1.2. Contextual Dimensions

3.2. Outline of the History of the Papacy

“And I tell you, you are Peter [gr. Petros], and on this rock [gr. petra] I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven”.(Matthew 16:18–19) [3]

3.3. Functions and Duties of the Pope

3.4. Death and Election of the Pope

4. Discussion

- elements of the sacred (temples, liturgical periods, prayers and hymns, clergy) serving as carriers of sacred values,

- the liturgical function of both material and immaterial cultural elements used in religious practices and rituals [39],

- the protection and management of heritage [32].

5. Conclusions

5.1. Achieving the Cognitive Goal

5.2. Future Research Directions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pew Research Center. The Global Religious Landscape: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Major Religious Groups as of 2010; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: https://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2014/01/global-religion-full.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition; Catholic Bible Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Second Vatican Council. Lumen Gentium: Dogmatic Constitution on the Church; Documents of Vatican II; Vatican Publishing House: Vatican City, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Code of Canon Law. Codex Iuris Canonici; Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Vatican City, 1983; Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/cod-iuris-canonici/cic_index_en.html (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- John Paul II. Ecclesia de Eucharistia; Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Vatican City, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Szromek, A.; Polok, G.; Bugdol, M. The level of trust of young Catholics in the institutional representatives of the Catholic Church: An example from Poland. Religions 2024, 15, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2003; Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Vatican City (No. 286); UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/286 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Bouchenak, M. Editorial. Mus. Int. 2004, 56, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsivolas, T. Law and Religious Cultural Heritage in Europe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Report on the Preliminary Study on the Advisability of Regulating Internationally, Through a New Standard-Setting Instrument, the Protection of Traditional Culture and Folklore (161 EX/15); UNESCO: Paris, France, 2001; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000122585 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Volzone, R.; Niglio, O.; Becherini, P. Integration of knowledge-based documentation methodologies and digital information for the study of religious complex heritage sites in the south of Portugal. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2022, 24, e00208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Bai, C.; Wang, M.; Ma, T.; Ma, H.; Zhang, G.; Wang, W.; Guo, Z.; Sun, Y.; et al. Identification of the key factors influencing biodeterioration of open-air cultural heritage in the temperate climate zone of China. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2024, 196, 105954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Liddo, F.; Morano, P.; Tajani, F. Cultural and religious heritage enhancement initiatives: A logic-operative method for the verification of the financial feasibility. J. Cult. Herit. 2023, 62, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allal-Chérif, O. Intelligent cathedrals: Using AR, VR and AI to provide an intense cultural, historical, and religious visitor experience. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 178, 121604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okyere-Manu, B.; Morgan, S.N.; Nwosimiri, O. Cultural, ethical, and religious perspectives on environment preservation. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 85B, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Historic Centre of Rome, the Properties of the Holy See in That City Enjoying Extraterritorial Rights and San Paolo Fuori le Mura (No. 91); UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/91/ (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Poulios, I. The Past in the Present: A Living Heritage Approach—Meteora, Greece; UCL Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Heritage: Critical Approaches; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.D. Chosen Peoples: Sacred Sources of National Identity; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B.; Ashworth, G.J.; Tunbridge, J.E. A Geography of Heritage: Power, Culture and Economy; Arnold Publishers: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Grim, B.J.; Grim, M.E. The World’s Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Managing Religious Heritage; UNESCO World Heritage Papers; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Paine, C. Religious Objects in Museums: A Handbook for Curators; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Garelli, F. Religione All’Italia. L’anima del Paese Messa a Nudo; Il Mulino: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt, J. The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy; Dover Publications: Garden City, NY, USA, 1860. [Google Scholar]

- Melloni, A. (Ed.) Cristiani d’Italia: Chiese, Società, Stato, 1861–2011; Treccani: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nuryanti, W. Heritage and postmodern tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, M.T.; Hagsten, E. Factors with ambiguous qualities for Cultural World Heritage. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 66, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, M.; Fernández-Álvarez, O. Cultural Tourism, Religion and Religious Heritage in Castile and León, Spain. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2022, 10, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Pande, K.; Shi, F. Managing visitor experience at religious heritage sites. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2023, 29, 100800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Cárdenas, R. Relevance of religious and spiritual aspects as components of intangible heritage. J. Tour. Herit. Res. 2022, 5, 136–152. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Ikebe, K.; Kinoshita, T.; Chen, J.; Su, D.; Xie, J. How Heritage Promotes Social Cohesion: An Urban Survey from Nara City, Japan. Cities 2024, 149, 104985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedecho, E.K.; Kim, S. Exploring the spiritual well-being experiences of transnational religious festival attendees: A grounded theory approach. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 53, 101289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qui, Q. Identifying the role of intangible cultural heritage in distinguishing cities: A social media study of heritage, place, and sense in Guangzhou, China. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2023, 27, 100764. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. Theorizing Heritage. Ethnomusicology 2004, 48, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjepour, N.; Memar, S.; Sheikh, S.H. Examining the role of religious identity in the preservation of cultural heritage among youth in Isfahan, Iran. Appl. Sociol. 2015, 26, 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Amsikan, M. The Role of Symbolism in Liturgical Rites: A Theological and Anthropological Perspective. J. Acad. Sci. 2025, 2, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemar, A. Parental Influence and Intergenerational Transmission of Religious Belief, Attitudes, and Practices: Recent Evidence from the United States. Religions 2023, 14, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamratrithirong, A.; Miller, B.A.; Byrnes, H.F.; Rhucharoenpornpanich, O.; Cupp, P.K.; Rosati, M.J.; Fongkaew, W.; Atwood, K.A.; Todd, M. Intergenerational transmission of religious beliefs and practices and the reduction of adolescent delinquency in urban Thailand. J. Adolesc. 2013, 36, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youvan, D.C. Discerning the Papacy: A Biblical and Historical Examination of Peter’s Authority in the Early Church. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Douglas-Youvan/publication/382591200_Discerning_the_Papacy_A_Biblical_and_Historical_Examination_of_Peter’s_Authority_in_the_Early_Church/links/66a3ee5575fcd863e5df5c7a/Discerning-the-Papacy-A-Biblical-and-Historical-Examination-of-Peters-Authority-in-the-Early-Church.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Demacopoulos, G.E. The Invention of Peter: Apostolic Discourse and Papal Authority in Late Antiquity; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, D. Leo the Great on the Supremacy of the Bishop of Rome. Andrews Univ. Semin. Stud. J. 2015, 1, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Fortescue, A. The Early Papacy: To the Synod of Chalcedon in 451, 4th ed.; Ignatius Press: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baldovin, J.F. The “Classic” Age of Christian Worship, 4th–6th Century. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutie, J. A Critical Examination of the Church’s Reception of Emperor Constantine’s Edict of Milan of AD 313. Perichoresis 2021, 19, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dictatus Papae. Dictatus Papae: Papal Principles Compiled by Hildebrand (A.D. 1075). Available online: https://www.csun.edu/~hcfll004/dict_pap.html (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Blumenthal, U.-R. Saint Gregory VII—Politics; Encyclopaedia Britannica: Chicago, IL, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Gregory-VII/Politics (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- MacCulloch, D. The Reformation: A History; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barbierato, F. Sobór Trydencki. In Encyklopedia Filozofii Renesansu; Sgarbi, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, P. Papal Infallibility at the First Vatican Council. Faith Mov. 2020, VI–VIII, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Second Vatican Council. Sacrosanctum Concilium: Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy. 1963. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19631204_sacrosanctum-concilium_en.html (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Cavadini, J.; Healy, M.; Weinandy, T. The liturgy prior to Vatican II and the Council’s reforms. Church Life J. 2022. Available online: https://churchlifejournal.nd.edu/articles/the-liturgy-prior-to-vatican-ii-and-the-councils-reforms/ (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- International Theological Commission. Synodality in the Life and Mission of the Church. 2018. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/cti_documents/rc_cti_20180302_sinodalita_en.html (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Francis. For a synodal Church: Communion, participation, mission—Final document. In XVI Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops; Vatican Publishing House: Vatican City, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- First Vatican Council. Pastor aeternus. In Constitutiones Dogmaticae; Vatican Council I: Vatican City, 1870. [Google Scholar]

- John Paul II. Universi Dominici Gregis; Vatican Publishing House: Vatican City, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- John Paul II. Ut Unum Sint; Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Vatican City, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Congregation for the Causes of Saints. Norms to Be Observed in Inquiries Made by Bishops in the Causes of Saints (Normae servandae in Inquisitionibus ab Episcopis Faciendis in Causis Sanctorum); Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Vatican City, 1983; Available online: https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/csaints/documents/rc_con_csaints_doc_07021983_norme_en.html (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Paul VI. Ingravescentem Aetatem; Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Vatican City, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Francis. Apostolic Constitution Praedicate Evangelium on the Roman Curia and the Service of the Universal Church; Vatican City, 2022. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_constitutions/documents/20220319-costituzione-ap-praedicate-evangelium.html (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Ullmann, W. A Short History of the Papacy in the Middle Ages; Methuen: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, R. The Barbarian Conversion: From Paganism to Christianity; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal, U.-R. The Investiture Controversy: Church and Monarchy from the Ninth to the Twelfth Century; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1988; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fht77 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Rollo-Koster, J. Avignon and Its Papacy, 1309–1417: Popes, Institutions, and Society; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Latourette, K.S. A History of Christianity: Volume II: Reformation to the Present; Rev. Ed.; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Wollpert, R. Lexikon der Päpste; Verlag Friedrich Pustet: Regensburg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory X. Ubi periculum [Apostolic constitution]. In Conciliorum Oecumenicorum Decreta, 3rd ed.; Istituto per le Scienze Religiose: Bologna, Italy, 1274; pp. 287–290. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory XV. Aeterni Patris Filius [Apostolic constitution]. In Bullarium Romanum; Typographia Vaticana: Rome, Italy, 1621; Volume 11, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict XVI. De Aliquibus Mutationibus in Normis de Electione Romani Pontificis [Apostolic Letter Issued Motu Proprio]; Vatican Publishing House: Vatican City, 2007; Available online: https://www.vatican.va (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. Directory for the Application of Principles and Norms on Ecumenism (nn. 93–99); Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Vatican City, 1993; Available online: https://www.christianunity.va/content/unitacristiani/en/documenti/testo-in-inglese.html (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Muratori, L.A. Rerum Italicarum Scriptores; ex Typographia Societatis Palatinae: Mediolan, Italy, 1727. [Google Scholar]

- Waitz, G. Libelli de Lite: Geschichten und Urkunden zur Geschichte des Investiturstreites; Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Hannover, Germany, 1883. [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli, L. Ordo Exsequiarum Romani Pontificis; Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Vatican City, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Office for the Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme Pontiff. Ordo Exsequiarum Romani Pontificis (Aktualizacja); Office for the Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme Pontiff: Vatican City, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith. History. Available online: https://www.doctrinafidei.va/en/profilo/storia.html (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Pontifical Swiss Guard, Secretariat of State of the Holy See. Institution, Nature and Dependence: Corpo Della Guardia Svizzera Pontificia: Profilo. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/romancuria/en/guardia-svizzera-pontificia/corpo-della-guardia-svizzera-pontificia/profilo.html (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Lipnicka, M.; Peciakowski, T. Religious Self-Identification and Culture—About the Role of Religiosity in Cultural Participation. Religions 2021, 12, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, H.J. Symbolic Ethnicity: The Future of Ethnic Groups and Cultures in America. Ethn. Racial Stud. 1979, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catechism of the Catholic Church; Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Vatican City, 1994.

- Polok, G.; Szromek, A. Religious and Moral Attitudes of Catholics from Generation Z. Religions 2024, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gish, D. Pope Julius II at the Basilica di San Pietro, The Musei Vaticani, and Basilica di San Pietro in Vincoli. In People and Places of the Roman Past; Hatlie, P., Ed.; ARC Humanities Press: Ashland, OH, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chng, K.S.; Narayanan, S. Culture and Social Identity in Preserving Cultural Heritage: An Experimental Study. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2017, 44, 1078–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure; Aldine Publishing: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse, H. Modes of Religiosity; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. Evolving Heritage in Modern China: Transforming Religious Sites for Preservation and Development. Built Herit. 2024, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, J. The Impact of Religious Rituals on Cultural Identity: Review of the Relationship between Religious Practices and Cultural Belonging. Int. J. Cult. Relig. Stud. 2023, 4, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Functions | Resulting Task |

|---|---|

| Spiritual functions |

|

| Doctrinal functions |

|

| Jurisdictional functions |

|

| Representative functions |

|

| Other papal functions |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szromek, A.R. The Papacy as Intangible Cultural Heritage. Heritage 2025, 8, 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8080323

Szromek AR. The Papacy as Intangible Cultural Heritage. Heritage. 2025; 8(8):323. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8080323

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzromek, Adam R. 2025. "The Papacy as Intangible Cultural Heritage" Heritage 8, no. 8: 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8080323

APA StyleSzromek, A. R. (2025). The Papacy as Intangible Cultural Heritage. Heritage, 8(8), 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8080323