1. Introduction

The transformation of the museum experience in the digital age has raised profound theoretical questions about meaning construction in algorithm-driven virtual museums [

1,

2]. As museums increasingly offer online collections, virtual tours [

3], and personalised content curated by algorithms [

3,

4,

5], scholars have debated how these new modalities affect the interpretation and significance of cultural objects. A common point of departure is Walter Benjamin’s famous diagnosis that mechanical reproduction strips artworks of their unique presence or aura [

6]. Benjamin argued that “even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be” [

6]. By this account, the physical encounter with an authentic object has an irreplaceable value, a “peculiar web of space and time” that virtual displays cannot fully replicate. Such an aura-loss perspective highlights a genuine challenge: when a museum’s treasures are rendered into pixels and disseminated globally, do they lose the ineffable qualities that lent them authority and meaning in situ [

7,

8]?

Opposing views contend that meaning can survive, or even thrive, in digital form through careful continuity of signs and contexts, a stance we might call semiotic continuity. From this angle, a museum exhibit is fundamentally a constructed narrative of signs (objects, text labels, spatial arrangement) that can be reconfigured without annihilating meaning [

9]. Semiotic theorists of the museum note that exhibitions are cultural texts composed of multiple sign systems, and thus, a digital exhibition can, in principle, reproduce the signifying structure of a physical one. Since the late 20th century, scholars have applied semiotics to museums, like Hodge and D’Souza’s 1979 analysis of a museum gallery to demonstrate that museum displays function as complex communications [

10], with objects, lighting, layout, and language all contributing to meaning. Hilde Hein, for instance, observes that the museum “experience does not depend on mediation by an authentic object. The experience might be triggered by a multitude of devices, not all of which are real, or genuine, or material” [

11]. What matters is not the aura of the original artefact per se, but the network of references and interpretations through which audiences make sense of what they see [

12,

13,

14]. Proponents of semiotic continuity thus focus on preserving context and interpretation in virtual displays, ensuring that digital surrogates are situated within rich explanatory frameworks so that the signified the cultural and historical meanings remain coherent. In this view, meaning is not destroyed by digitisation; rather, it migrates into new sign contexts that a well-designed virtual exhibit can provide.

Meanwhile, debates about technology’s broader social impact have filtered into museum theory as technological optimism vs. critical technopessimism. On one hand, digital and algorithmic curation are celebrated as heralding a new democratisation of culture. No longer confined to those who can visit elite institutions, great works are now accessible to anyone with an internet connection. Early digital museum advocates envisioned the web as a means to “open up to new audiences” and eliminate the museum’s aura of exclusivity [

15,

16,

17]. Indeed, within a few years, it was generally acknowledged that museums have gained significantly from the widespread dissemination of information, an added step towards the democratisation of culture [

1,

18,

19]. Such technological optimism holds that algorithmic systems like recommendation engines on museum websites or art apps can personalise and enhance user engagement, tailoring content to individual interests and thus deepening the relevance of cultural heritage for each viewer. From this perspective, the virtual museum becomes a more inclusive, interactive forum—a realisation of what some have called the “post-museum” or a “museum without walls” [

7], freed from geographic and logistical barriers.

On the other hand, critical technopessimism urges caution, pointing out that algorithmic curation might undermine the very goals museums seek to achieve. Critics note that simply increasing access does not guarantee meaningful engagement or understanding [

20,

21,

22]. The authority of museums, their ability to provide trusted, contextualised knowledge, can be eroded when the curatorial narrative is replaced or overridden by opaque algorithms [

4,

23]. Unlike a human curator who consciously constructs an exhibit to convey interpretive insights, an algorithm might sort and display items based on popularity, user profiling, or click metrics, potentially decontextualising objects from their historical and cultural frameworks [

3]. Furthermore, the corporate and computational logics that drive many algorithms can embed bias and promote commodification. They risk treating cultural material as just another consumable item optimised for clicks and dwell-time—an outcome that recalls Adorno and Horkheimer’s critique of the culture industry [

24]. In the worst technopessimist scenario, the virtual museum becomes a passive entertainment feed, reinforcing prevailing tastes and ideologies through filter bubbles and personalised echo chambers, rather than challenging and expanding the visitor’s horizons. As Eli Pariser warned in the context of online information, algorithmic filters can “close us off to new ideas, subjects, and important information”, creating the impression that “our narrow self-interest is all that exists” [

25]. Translating this concern to museums: if each visitor is only shown artworks like those they already like, the educative, horizon-broadening mission of the museum is at risk.

Each of these approaches—aura-loss, semiotic continuity, technological optimism, and technopessimism—isolates a crucial aspect of the problem. The aura perspective foregrounds authenticity and the phenomenology of presence; the semiotic view emphasises interpretation and communicative context; the optimistic stance focuses on access and user empowerment; the critical stance focuses on power, ideology, and the integrity of cultural narratives. Yet taken in isolation, each is incomplete. The central research problem this paper addresses is how to formulate a unified theoretical model for meaning construction in algorithm-driven virtual museums, one that can integrate these disparate insights and critically examine the new reality of algorithmic mediation. We confront a dialectical challenge: the digital museum seems to generate a series of oppositions—original vs. copy, human curator vs. machine algorithm, democratisation vs. commodification, meaning as intrinsic aura vs. meaning as contextual signification. How might these tensions be resolved or at least mapped within a single framework that does justice to all?

In what follows, we first analyse the conceptual foundations that such a framework must encompass, engaging with the theories of Benjamin, Sebeok, Barthes, Adorno, and others that each shed light on different facets of the issue. We then propose a synthesising approach termed the Dialectical Modelling Nexus (DMN). The choice of theorists—Benjamin, Sebeok, Barthes, and Adorno—is purposive, as each provides an essential lens required to build a holistic model. This framework is “dialectical” in that it treats meaning-making as arising from the interplay of opposing forces (e.g., authenticity and reproducibility, individual experience and collective signification, human intention and algorithmic operation), and “semiotic” in that it models these processes as exchanges of signs within cultural systems. By drawing these threads together, the DMN aims to diagnose how algorithmic curation actively shapes (and sometimes distorts) meaning, and to guide museum practitioners in critically engaging with these systems. The final sections of the paper elaborate on the DMN in detail and discuss its implications. Philosophically, for how we understand authenticity, interpretation, and agency in the digital context, and practically, for how virtual museums might be designed or critiqued to ensure richer and more reflective experiences for their audiences.

2. From Aura to Algorithm

2.1. Aura, Authenticity, and the Fate of Art in the Digital Age

Any discussion of meaning in virtual museums must reckon with Walter Benjamin’s enduring question: What becomes of the “aura” of an artwork in the age of technical reproduction [

6]? Benjamin defined aura as the “unique phenomenon of a distance, however close it may be” [

6]. In simpler terms, aura is the powerful feeling of presence and authority that comes from being in the same physical space as the one-and-only original object, steeped in its own unique history. In a traditional museum, this aura is cultivated by the physical presence of original artefacts—a sensation linked to knowing “this is the real thing”, imbued with a lineage of history and ritual. Visitors often feel a quasi-spiritual connection when standing before an ancient relic or a master painting [

26], a sensation linked to knowing “this is the real thing”, imbued with a lineage of history and ritual [

27]. Benjamin observed that modern reproduction techniques like photography, film, and by extension digital media fundamentally change this equation: the work of art “detached from the domain of tradition” can be multiplied and transmitted, thereby diminishing the authority of the object rooted in its unique time and place [

6]. With the museum going online, this detachment is taken to an extreme—art is not only reproducible, it is effectively ubiquitous [

18]. A high-resolution image of the Mona Lisa on one’s home screen is available at the click of a button [

28], potentially raising the same issue Benjamin foresaw: the erosion of the artwork’s aura through unlimited accessibility.

However, contemporary thinkers have complicated Benjamin’s stark dichotomy of auratic original vs. de-auratised copy. Some propose that digital interfaces can generate new kinds of aura or authenticity. For example, museum scholar Susan Hazan suggests the emergence of “a new cultural phenomenon, the virtual aura” [

29], and Bruno Latour and Adam Lowe argue that aura can migrate from the original to high-quality facsimiles under the right conditions [

30]. These views imply that aura is not an absolute property residing immutably in an object, but a relational effect—a product of how viewers perceive an object within a given context. An algorithmically curated presentation might conceivably create an aura-like effect by carefully contextualising digital objects, personalising the narrative to the viewer, or employing immersive technologies that simulate a sense of place [

31]. One could imagine, for instance, a virtual reality simulation of an archaeological site that gives a remote viewer a feeling of solemn presence and authenticity comparable to being on location [

32,

33,

34]. In that sense, aura in the virtual museum may be diminished in its traditional “here and now” aspect, yet partially reconstituted in new forms—a point of optimism for those who hope technology can reinvest digital culture with depth. Latour and Lowe make this point with digitally crafted facsimiles: when a faithful copy of a fresco is installed in its original chapel, visitors still sense much of the work’s aura. Aura, therefore, can “migrate” through context and ritual rather than reside solely in the original material [

35].

Nevertheless, a critical stance influenced by Benjamin remains sceptical of such claims. The ease of reproduction and dissemination, while democratising, risks making the experience of art too transient and ubiquitous to carry an aura [

31]. Benjamin noted that in reproduced art, “transitoriness and reproducibility” replace the “uniqueness and permanence” of the original. Applied today, one might argue that algorithmic feeds—often populated by endless streams of images—encourage a quick, scrolling consumption that is antithetical to the slow, ritual appreciation that aura presupposes. The very strengths of digital media (speed, abundance, personalisation) might thus undermine the concentration and historical consciousness needed for meaning to fully crystallise [

14].

Benjamin also foresaw a dialectical flip side: the loss of aura could have liberating effects, freeing art from its cult of authenticity and making it more accessible for political critique and mass participation [

6]. This insight aligns with the technological optimism viewpoint that digital reproduction democratises culture [

18]. In practice, the aura dialectic in virtual museums is complex. On one hand, something is lost when art is virtualised (a certain gravitas tied to physical presence); on the other hand, something is gained or transformed (new contexts, new participatory modes, even a form of “virtual aura” through personalisation). A theoretical framework for virtual museum meaning must therefore account for both poles: the fact that an object’s singular authenticity is altered by digitisation, and the fact that meaning can still be powerfully conveyed, even augmented, through thoughtful digital recontextualisation. Benjamin’s insight is a starting thesis that must be both acknowledged and transcended in a new model. Aura becomes one element, a kind of value or meaning-marker that can be diminished, preserved, or reimagined by the design of virtual curatorial systems. However, to fully understand how meaning operates with or without aura, we must shift our focus from the object itself to the systems of communication in which it is embedded. This requires a semiotic perspective, which views the museum not as a collection of things, but as a network of signs.

2.2. Museums as Sign Networks

If aura emphasises an object’s unique presence, a semiotic perspective shifts focus to the sign systems and interpretive structures through which museums communicate meaning. A museum exhibit can be viewed as a language: objects are the vocabulary, their arrangement and accompanying texts form a grammar and syntax that conveys messages about history, art, or science [

26,

27]. Pioneering work in museum semiotics, such as Duncan Cameron’s essays on the museum’s “language” of display and studies by researchers like Robert Hodge and Mary-Anne D’Souza, underscored that museums do not merely present things but rather tell stories and construct knowledge through the selection and juxtaposition of those things [

10,

36,

37]. The key implication is that meaning in a museum arises from a contextual network of signs. Move an artefact from one display to another, change its caption or lighting, and you potentially change its meaning [

9]. As Cameron expressed, the “problems in the language of museum interpretation” centre on how the arrangement of objects and information creates or obscures meaning [

37].

In the digital realm, this insight suggests that a virtual museum need not be a lesser experience so long as the necessary signifying framework is provided. The “semiotic continuity” approach builds on exactly this point: if the virtual platform can supply analogous context through descriptive text, thematic groupings, embedded media, and interactive guides, then the interpretive meaning of objects can be continuous with that in the physical gallery [

9]. For instance, a well-designed virtual exhibition might include not only high-resolution images of artefacts but also rich annotations like audio commentary, scholarly essays, links to related items, which together form a dense web of signification around each artefact, much as a physical exhibit does with labels, catalogues, and guided tours. In this way, the signified concepts, the ideas, values, and stories associated with the object, can be preserved or even enriched, despite the shift in medium [

23]. The authentic object itself may be absent, but if the signs that convey its significance are present, the audience can construct meaning in similar ways.

To clarify how meaning is built up and may be reconfigured by algorithms, we adopt Sebeok and Danesi’s three-tier Modeling Systems Theory. The primary modelling system (PMS) is the universal, species-specific power of mimetic or simulative modelling: every animal can construct an iconic internal model by reproducing some perceivable trait of its Umwelt [

38]. In a museum, this is the simple act of looking at an artefact and recognising its form, colour, and texture. The secondary modelling system (SMS) is superimposed upon this mimetic base and enables both indexical and extensional reference, signs that point to, and stand for, entities beyond the here-and-now. In humans, this capacity culminates in language, whose lexical and grammatical resources permit reference to absent, hypothetical, or otherwise non-perceptible objects [

38]. This is engaged when a visitor reads a label (“This is a Roman coin”) or understands that a skull-and-crossbones symbol on a bottle means “poison”. Finally, the tertiary modelling system (TMS) is the most sophisticated layer, where we use complex symbolic systems to create overarching cultural narratives, myths, and scientific theories [

38]. Because each tier reorganises the semiotic resources of the one beneath it, a virtual-museum interface must preserve coherence across all three: its visual layout should respect iconic perception (PMS), its metadata and captions must enable reliable indexical and extensional reference (SMS), and its overarching narrative or gallery logic ought to sustain the symbolic, culturally saturated meanings characteristic of tertiary modelling [

39]. Any algorithm that reorders objects, therefore, becomes an additional “modelling agent” whose outputs must be critically checked against these layered semiotic requirements.

In museum terms, we might interpret an exhibition as a tertiary modelling system—a cultural narrative that humans create to model some aspect of the world, using objects and signs to tell a story. The museum thus engages all three levels: visitors use their primary modelling system to visually perceive objects; they use secondary modelling (language) when reading labels or listening to guides; and they grasp the tertiary modelling when they understand the overarching theme or message (e.g., “this exhibit shows the evolution of writing systems” is a conceptual model of a historical process).

Applying Sebeok’s concept to algorithmic curation, the virtual museum interface can be seen as a compound modelling system that must integrate several layers of semiosis. The visual display of objects (thumbnails, layout on screen) taps into our primary perceptual modelling. The linguistic or symbolic annotations (titles, descriptions, categories) engage the secondary modelling system of language and symbols. The overarching organisation—perhaps the way content is grouped into virtual “galleries” or thematic sections, or the narrative a recommender system implicitly creates—corresponds to tertiary modelling, akin to myth or narrative. A successful virtual curation maintains cohesion across these layers, ensuring that the way objects are algorithmically selected and arranged (the algorithm’s “model” of content relevance) does not break the narrative logic or dilute the contextual meaning that a human curator would provide [

31].

However, if left unexamined, an algorithm might inadvertently create juxtapositions that confuse or distort meaning. For example, clustering items by user preference can mix cultural contexts in a way a human curator would avoid [

23]. It is here that MST offers a valuable perspective: it reminds us that humans impart meaning by situating signs within layered models of understanding, and any algorithmic approach to curation must grapple with those layers. The algorithm, in effect, becomes a new agent in the semiotic process, a “modelling agent” that has its own way of relating signs. Crucially, its way of modelling (often through statistical association or content similarity metrics) may not align with traditional cultural models. Thus, the theoretical framework we build will need to consider how these modelling processes interact, the curator’s model, the algorithm’s model, and the visitor’s own cognitive model, in producing the final experienced meaning [

40]. In short, the museum is a multi-layered sign system, and any unified theory must accommodate the interplay of these layers, especially as algorithms intervene in the chain from object to interpretation.

2.3. Myth and Ideology

Beyond the structural layering of signs, semiotics also alerts us to the content of the messages and the ideologies they carry [

41]. Here, we turn to Roland Barthes’s notion of myth as a second-order semiological system. Barthes famously analysed how cultural artefacts and narratives carry connotations that align with social and political ideologies, effectively turning specific cultural meanings into seemingly natural myths. A myth, in Barthes’s formulation, is “a system of communication… a mode of signification, a form” [

41]. For Barthes, a myth is not a falsehood, but a powerful cultural message disguised as nature. It works by taking a complete sign (a signifier linked to a signified) and using it as the building block for a new, larger message [

42]. Consider a simple museum example. At the first level, a display case contains the Rosetta Stone. The object itself (the signifier) and its direct, literal meaning (“a royal decree from ancient Egypt”, the signified) form a complete sign. But the museum then uses this entire sign as a new signifier for a second, grander message: the myth of “Humanity’s Triumph Over the Past” or “The Key to Unlocking Civilisation”. This second meaning feels natural and obvious, but it is an ideological construct. Myth, for Barthes, is this process of making culture feel like nature. It “naturalises” these messages makes cultural and historical constructs appear inevitable, timeless, or “just how things are”.

Museums, as repositories of cultural narratives, have long been vehicles for certain myths [

43,

44]. For instance, Barthes himself critiqued the famous 1955 photography exhibition The Family of Man (which later became a travelling museum exhibition) as constructing a myth of universal humanism that obscured differences in historical and social conditions [

41]. National museums often implicitly advance the myth of the nation’s historical greatness or progress by the way they curate artefacts [

45]. In semiotic terms, the museum takes concrete signs (objects with their immediate meanings) and uses them as signifiers for a higher-order concept (e.g., “the glory of Empire” or “the unity of humankind”), thereby constructing a myth. The visitor may absorb this message without realising it, because the museum’s authority and the ostensibly factual presentation mask the ideological leap.

When algorithms enter the picture, the concept of myth takes on new implications. Algorithms might create new myths in virtual museums, for example, the myth of algorithmic neutrality (the idea that what I see on my screen is simply what is most relevant or popular, presented objectively by a machine) [

46,

47], or the myth of personalised omniscience (the sense that the system “knows me” and will show me what matters, instilling trust that can be ideologically loaded) [

48]. These are ideological positions embedded in design. A visitor might not question why certain artworks keep showing up as “recommended”, the interface may feel intuitively tailored, masking the reality that specific values (popularity, similarity, corporate partnerships, etc.) are driving the selection.

In essence, Barthes’s myth concept allows us to critique the ideological underpinnings of algorithmic curation. Just as Barthes dissected the image of a saluting Black French soldier on a magazine cover as a myth of French imperial benevolence, we can interrogate a museum’s digital platform for the myths it perpetuates. For example, a personalised art feed might perpetuate the myth that art history is defined by these “masterpieces”, which always appear first (reinforcing a canonical bias), or the myth that your taste is king, implying that one need not step outside one’s comfort zone (an ideology of consumer-centric satisfaction). The very promise of personalisation carries a mythic undertone: “art should come to you, on your terms”, which dovetails with a broader neoliberal ideology of individualised convenience and consumption.

A theoretical model for meaning in virtual museums must include this semiotic-ideological critique to uncover how meaning might be skewed or pre-packaged by algorithmic mediation. It should prompt us to ask: What “mythologies” might an algorithm be inscribing into the museum experience? Are we mythologising technology as impartial? Are we inadvertently reinforcing cultural hierarchies by showing certain works more prominently? Barthes’s framework reminds us that meaning-making is never neutral; it often serves some conceptual agenda, consciously or not. Thus, our unified model will need a critical dimension that can account for and challenge the myths that crystallise when curatorial practice meets algorithmic systems.

2.4. Critique and Algorithmic Curation

The introduction of algorithms into the cultural sphere has frequently been met with concerns that echo the Frankfurt School’s critique of mass culture [

49,

50]. Adorno and Horkheimer argued that in industrialised capitalist society, culture (films, music, art) is produced in a standardised way to maximise consumption and reinforce the status quo, resulting in the loss of authenticity and critical potential in art [

24]. Key concepts from Adorno relevant here include commodification (turning cultural goods into marketable products), standardisation (formulaic production), and especially pseudo-individualisation. This is the illusion of personal choice that masks an underlying uniformity [

51]. For example, many pop songs are essentially very similar in structure, yet are marketed with slight differences to make them seem unique [

52].

In the context of virtual museums, we can ask: Are algorithms turning the curated experience into a commodified product? Are they imposing a standardised “formula” on what each user sees, under the guise of personalisation? Recent analyses suggest that algorithmic personalisation often operates within narrow templates [

12]. As one commentary notes, digital platforms provide users with content tailored to their preferences “while operating within narrow, standardised parameters” [

53]. This is essentially Adorno’s pseudo-individualisation writ large: the system gives the user a feeling of unique treatment, but the choice criteria are highly formulaic, like trending pieces, or items like ones already interacted with [

54]. The result can be a homogeneous experience disguised as personalised discovery [

47]. The museum equivalent might be an online gallery that looks customised for each visitor but is, in fact, drawing from the same pool of popular objects and arranging them according to a uniform algorithmic pattern. Pseudo-individuality, as Adorno put it, “…with an air of free choice, disguises the standardisation of production process” [

51].

Algorithms are typically deployed by large technology companies or under commercial paradigms, even museums often rely on platforms or software provided by tech firms, raising questions about monopoly and control akin to what Adorno described. If, say, a handful of recommendation algorithms or search engines determine global audiences’ exposure to art and heritage content, they hold enormous sway in shaping collective cultural memory [

14,

48]. Adorno’s worry that mass media could entrench dominant ideologies becomes pertinent: an algorithm might subtly favour content that is more “clickable” or aligns with mainstream tastes, thereby sidelining art that is challenging, avant-garde, or from marginalised groups. In museum terms, richly complex artefacts that require context might be filtered out in favour of immediately eye-catching images that maximise user dwell time, a dynamic like how social media algorithms favour sensational news over complex journalism. The outcome is a potential narrowing of the cultural spectrum presented, reinforcing what is easily digestible and marketable at the expense of works that require more effort to appreciate [

25]. In a traditional museum, while the curator’s narrative guides the visitor, the experience still allows for personal exploration, contemplation, and the chance encounter with the unexpected object that sparks insight [

9,

55]. In an algorithm-driven feed, however, the risk is that the visitor becomes a passive consumer of whatever is put in front of them, continuously scrolling or clicking in a state of mild diversion rather than active inquiry [

50]. This scenario aligns with Adorno’s notion of mass culture as fostering distraction and compliance, entertainment that keeps people amused and not asking too many questions. If a virtual museum’s personalisation is too frictionless, always giving the user what they already want or expect, the visitor may settle into a comfortable, uncritical consumption pattern [

12], in contrast to the ideal museum visit [

56].

That said, as with Benjamin’s aura, Adorno’s critique should be used dialectically rather than taken as a blanket condemnation. If conscientiously designed, it might be harnessed to counteract some culture industry effects. For instance, a museum could instruct its recommendation algorithm to maximise the diversity of content shown, thus deliberately breaking standardisation, or countering filter bubbles by injecting serendipity. Indeed, scholars have suggested leveraging algorithms to increase serendipitous discovery rather than eliminate it, by programming in diversity or randomness [

57,

58]. Similarly, personalisation can be used to draw users deeper into niche content. If someone shows interest in impressionist paintings, a clever system might next expose them to lesser-known impressionists or related movements, rather than just looping the same Monet and Renoir greatest hits. In this way, the technology could break the mass-culture cycle of repeating the familiar and instead serve as a bridge to more uncommon knowledge, analogous to a curator taking you from the popular wing into a side gallery you’d otherwise skip.

Adorno’s culture industry critique adds to our theoretical toolkit a focus on power, economics, and critical autonomy. It urges that any model of meaning in algorithmic curation does not ignore the material and institutional conditions under which algorithms operate. Museums may be non-profits with educational missions [

59], but the digital platforms they use and the user attention they compete for exist within a broader economy of data and attention.

The DMN framework we propose will integrate this perspective by asking: Who or what is determining the flow of cultural signs in the virtual museum? What values are inscribed in that determination (engagement metrics, commercialisation, or educational enrichment)? And how do those conditions enable or constrain the visitor’s own meaning-making agency? By keeping Adorno’s warnings in mind, our model stays alert to the risk that virtual museums might unknowingly drift towards being just another stream of consumable content, and it highlights the need for conscious countermeasures to preserve the space of reflection and critique that museums traditionally uphold.

3. Synthesising Core Tensions: The Case for a Dialectical Framework

Having reviewed these foundational theories, the unique aura of authenticity, the multi-layered semiosis of museum communication, the mythic narratives and ideological subtexts, and the critical theory of cultural commodification, we stand at a point where a synthesis becomes possible. Each theory highlights a different dimension of meaning-construction in the digital museum, and each also implicitly critiques the limitations of the others. The way forward is to think dialectically, to see the dynamic tensions not as irreconcilable opposites but as interacting forces that together produce the phenomenon we are studying.

We can summarise a few key dialectical tensions identified:

Authenticity and Reproducibility: There is a tension between the value of the original object’s authenticity (its aura in a specific time/place) and the value of wide distribution and accessibility through reproduction [

6]. A dialectical approach does not simply choose one side but examines how the interplay between these qualities shapes meaning. In a virtual museum, meaning may emerge in the negotiation between an awareness of what is lost (the aura, the physical presence) and what is gained (broader access, new contexts, personalisation) [

60]. The goal would be to harness the benefits of reproducibility (democratisation, connectivity) while devising ways to simulate or compensate for what aura provided (a sense of depth, aura-like context, ritual, etc.).

Human Curation and Algorithmic Curation: This is the tension between intentional, interpretive narrative shaped by human curators and automated, data-driven selection by algorithms. Rather than seeing the algorithm as a neutral tool or a usurper of human roles, a dialectical view considers the algorithm as a new participant in curation, whose “decisions” result from a different logic [

61]. The challenge is to integrate human contextual depth with the algorithmic capacity to scale and tailor; meaning will be co-constructed wherever these logics complement, clash, or correct one another [

4].

Personalisation and Standardisation: There is a contradiction between providing each visitor a unique, personalised journey and maintaining a shared cultural narrative or equity of experience [

53]. While Adorno warned of pseudo-individualisation, in a positive sense, personalisation can engage individuals deeply. Yet if everyone’s feed is totally unique, the museum ceases to be a communal forum and becomes a series of parallel solipsistic experiences [

62]. The dialectical goal would be a synthesis where personalisation is used to draw people in, but within boundaries that ensure exposure to a common body of knowledge or at least the possibility of converging discussions [

63]. In other words, calibrated personalisation that still retains a core of shared content or invites users to compare their experiences [

62]. Meaning in the DMN would thus be both personal (modelling in one’s own context) and collective (referencing a larger context that others also encounter).

Ease of Consumption and Depth of Engagement: Digital platforms excel at making content easy to consume, whereas meaningful museum experiences often require slowing down, contemplating, and grappling with complex ideas. This is another tension: algorithms might optimise for user engagement metrics that prefer ease and instant gratification, whereas curators seek user enlightenment, which might require difficulty and challenge [

23].

Neutral Presentation and Ideological Framing: Traditional curation often pretends to be neutral, though it never truly is. Algorithms similarly come with values built in, despite a veneer of objectivity [

47]. A dialectical approach insists on recognising bias and ideology (from Barthes and Adorno’s critiques) but also utilises the transparency and pluralism to counter them. For DMN, this means meaning is constructed critically: the framework itself should help identify where an apparently neutral presentation might be skewing interpretation and then introduce counter-signs or dialogues to balance it. For example, if an algorithm always shows European art first in search results, the framework will flag this and suggest a corrective measure to avoid establishing an inadvertent Eurocentric myth [

57,

61].

By framing the problem in terms of these interacting oppositions, we set the stage for the Dialectical Modelling Nexus. This concept is introduced as the point of convergence, the nexus where these dialectical threads are woven into a cohesive model. The term “nexus” implies a network or intersection of connections. Indeed, DMN envisions meaning-making in virtual museums as a network of relationships among content, curators, algorithms, and audiences, each bringing certain forces that must be balanced and interpreted.

The DMN will be characterised by the following general features:

Dialectical: Meaning emerges through the back-and-forth between contrasting elements (e.g., aura and reproduction, curator intent and algorithm output, expert narrative and user feedback). Instead of treating these contrasts as binaries where one must negate the other, DMN treats them as ongoing dialogues. Tensions are not only acknowledged but also seen as productive, driving the evolution of new meanings.

Semiotic: It emphasises that what is being exchanged and negotiated in this nexus are signs. The DMN is, in essence, a semiotic system where objects, descriptions, algorithms, and user responses all function as signs that influence one another. We build on Sebeok’s idea that humans interpret via modelling systems by including algorithmic mediation as part of semiosis.

Critical reflexive: Drawing from Barthes and Adorno, the DMN framework has a built-in awareness of myths and power dynamics. It does not assume the processes are neutral; rather, it explicitly looks for where meaning might be guided by hidden assumptions or external agendas, and it aims to make those visible for critique or recalibration.

Holistic: Rather than isolating one stage, like just the user’s interpretation or just the algorithm’s output, DMN attempts to provide a big picture view of how meaning is co-produced. In practical terms, it means our analysis or design guided by DMN will constantly zoom out to see the connections: how does a design decision at the interface level reverberate in user interpretation and link back to curatorial goals, etc.

Before presenting the DMN model in detail, it will be useful to outline its intended functions. Broadly, the DMN is meant to serve two main purposes:

First, the framework should allow us to dissect any given instance of algorithmic museum curation and map out how meaning is being formed. It prompts specific questions at each juncture: What is the role of authenticity here? What sign systems are at play (visual, textual, interactive)? Where might a myth or bias be creeping in? How are users contributing to or altering the meaning through their interactions? By systematically answering these, we can identify the strengths and weaknesses of a particular virtual exhibit. For example, an analysis might reveal, “This art recommendation page heavily prioritises paintings with high engagement, creating a myth that those are inherently the ‘best’ works, and it lacks context for non-specialist users, thus meaning skews towards popularity rather than historical significance.” Such a diagnosis is the first step towards improvement.

Second, the DMN is also prescriptive, offering guiding principles for museum professionals and designers to create more meaningful virtual experiences. It can inform design choices (e.g., ensure that alongside personalised suggestions, there is contextual information to ground the objects, balancing individual taste with scholarly context), content strategy (e.g., include alternative perspectives or counter-narratives to avoid a single story), and the integration of technology (e.g., use algorithms to enhance serendipity, not just reinforce known preferences). In effect, DMN can become part of a digital curation guideline: any new virtual platform or feature can be evaluated against it. Does it maintain a dialectical balance, does it preserve multi-layered meaning, does it encourage users to be interpreters and not just consumers?

Having set the conceptual stage, we now move to articulate the DMN framework explicitly and concretely. We will describe its components and how they interrelate, showing how prior theories are synthesised within it. Following that, we will discuss examples of how DMN can be applied and what implications it carries for the future of virtual curation.

4. The Dialectical Modelling Nexus: A Framework for Algorithmic Meaning

In this section, we introduce the DMN as a theoretical construct that encapsulates the dynamic process of meaning-making in algorithm-driven virtual museums. The DMN is “dialectical” in that it centres on relationships of tension and interaction, rather than isolating elements like aura or algorithm in a vacuum; it examines how they confront and influence each other. It is “modelling” in that it conceives each participant in the process (the museum institution, the technological system, and the audience) as operating via semiotic models of the content. And it is a “nexus” because it is essentially a network where these various models and influences meet and must be negotiated.

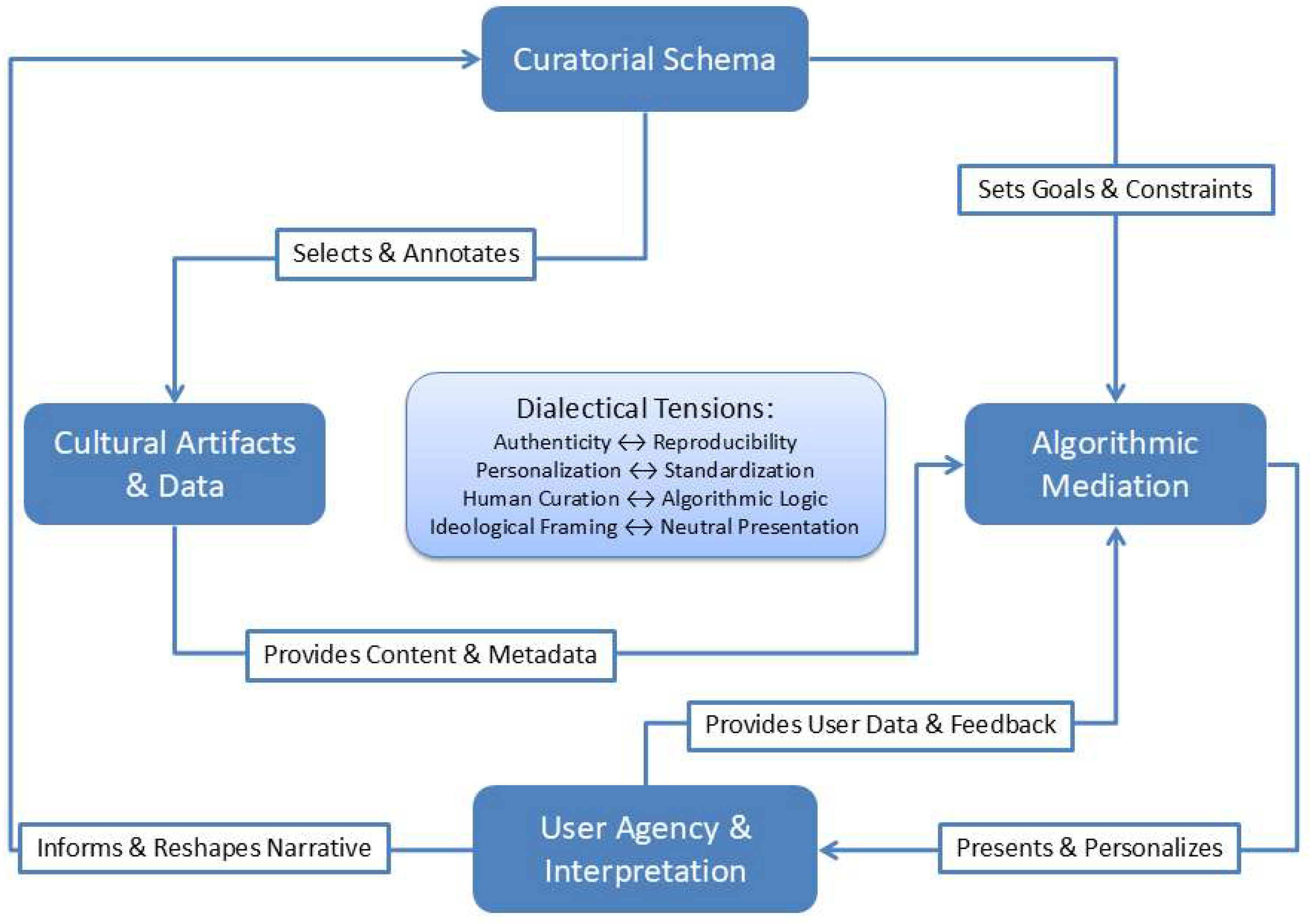

The Dialectical Modelling Nexus (DMN) is a conceptual framework designed to analyse and guide the co-creation of meaning in algorithmically-mediated virtual museums. It models this process as a dynamic, interactive network of four primary components: (1) Cultural Artifacts and Data, the raw semiotic material; (2) The Curatorial Schema, the intended narrative and interpretive goals set by human experts; (3) Algorithmic Mediation, the computational systems that select, filter, and present content based on encoded rules and user data; and (4) User Agency and Interpretation, the visitor’s active role in navigating, interpreting, and contributing back to the system. Meaning within the DMN is not located in any single component but emerges from the continuous, dialectical interplay between them—a feedback loop where curatorial intent is translated by algorithms, experienced by users, and in turn, potentially reshaped by user behaviour and feedback. To visualise this dynamic,

Figure 1 presents a schema of the Dialectical Modelling Nexus. This section will now unpack this model, detailing each component and the principles that govern their interaction.

4.1. Components of the DMN

We can delineate several primary components in the meaning-construction nexus of a virtual museum, each corresponding to a role in the process:

Cultural Artefacts and Data: This includes the digital representations of artworks or artefacts (images, 3D models, videos) along with their associated data (metadata like titles, artist, origin, descriptions, and possibly user-generated data like tags or comments). These are the raw signifiers available to be curated. In a way, this component is akin to Benjamin’s “originals”, except that here they are usually reproductions. However, they carry with them traces of aura and the factual information that anchors their primary meaning. This database of content is the foundation upon which all else builds; its breadth and quality set the stage for how much meaning can be extracted or lost. For instance, a richly annotated artefact provides more semiotic material for the system to work with than a bare image with only a title.

Curatorial Schema: This refers to the framework of interpretation and narrative devised by human experts (curators, educators, content strategists). It encompasses the themes chosen for presentation, the selection of which pieces to highlight, the explanatory texts written, and the pedagogical or interpretive goals set. In a traditional setting, this schema might be embodied in an exhibition plan or a catalogue [

64]. In a virtual setting, it might take the form of curated galleries, editorial content on the site, or rules like “ensure representation of all periods” that the museum staff impose on the content selection. The curatorial schema is essentially the human modelling system at work—it is informed by disciplinary knowledge (art history, anthropology, etc.) and by museological principles (like storytelling, educational flow). It ensures that there is coherence and intent behind the presentation. For example, a curator might establish a schema that pairs works from different cultures to draw out contrasts; this intention should ideally be honoured or at least known by the algorithm.

Algorithmic Mediation: This can be understood as the algorithm’s specific model for particular representations, aligning with Yu’s conceptualisation of modelling as a “slice” [

65]. Modern algorithms in this context could include recommendation engines (collaborative or content-based filtering), search algorithms ranking results, or adaptive interfaces that rearrange themselves based on user data. The algorithmic model includes the criteria and objectives set in code: e.g., “recommend items with the highest probability of user click based on similarity”, or “cluster artworks by visual features”. It also includes any learned biases, for instance, if an AI is trained on existing user behaviour, it might internalise popularity biases. This component is dynamic; it responds to user input and changes the content accordingly. It is helpful to personify it slightly: the algorithm “tries” to model what the user wants or what content is related, but its understanding is quantitatively driven, lacking cultural judgment unless programmed in. This is where a lot of the dialectical action happens: the algorithmic decisions might support or conflict with the curatorial schema and will directly shape the user’s view [

13,

61].

User Agency and Interpretation: The visitor (user) is not a passive node in this nexus, but their mode of engagement is not uniform [

66]. Users select which paths to follow, and in doing so, they exercise agency that can either align with or deviate from the curator’s narrative. They also contribute back to the system (explicitly via feedback, ratings, comments, or implicitly via their clickstream data, which the algorithm can use). Each user essentially has their umwelt of the museum content, shaped by personal context. In aggregate, users might even create emergent patterns of meaning, for instance, if many users link two objects by frequently viewing them in sequence, that’s a connection outside the original schema, but now part of the experience [

67]. Meaning is constructed in the mind of the visitor, and each visitor member might construct a slightly different meaning. In reality, user agency manifests across a spectrum. We can identify at least three common types: the Goal-Directed User, who seeks specific information; the Casual Browser, who skims for aesthetic pleasure or serendipitous encounters; and the Critical Explorer, who is motivated to engage deeply with complex narratives. A robust DMN framework must account for this diversity. Its goal should be to act as an adaptive scaffold, meeting users where they are and then providing pathways towards deeper engagement. For the Goal-Directed User, the algorithm should first provide efficient access to their target but then leverage that context to introduce dialectically related content—a counter-narrative, a thematically linked but culturally distinct object—thereby opening a door to exploration they did not initially seek. For the Casual Browser, the system can initially cater to aesthetic appeal but subtly embed context—a provocative question alongside an image, a link to the artist’s turbulent life—using moments of visual pleasure as hooks for narrative depth. The system can then learn which hooks are effective for which users. In this adaptive model, the DMN is not a rigid structure but a dynamic strategy. The algorithm’s role is not just to personalise, but to gently challenge and guide, transforming a user’s initial interaction style into a richer, more reflective experience. Meaning is thus constructed not only by the user’s interpretation but by the system’s ability to skillfully mediate the journey between different modes of engagement.

These components interact continuously. We can visualise the DMN as a loop or web: the curatorial schema informs both which artefacts/data are highlighted and how the algorithm is configured. The algorithmic mediation takes the artefacts (under those curatorial constraints) and presents them to the user, while also taking in user feedback and behaviour data to adjust what it shows next. The user, encountering the artefacts through the algorithmic lens, interprets them and potentially feeds back into the system. This may prompt curators to adjust the schema. For instance, analytics show users consistently misunderstanding something, curators might add more explanation, or an adaptation of the schema after seeing user behaviour. Likewise, curators notice that the algorithm hides some important items, and they intervene. Thus, in a full DMN cycle, every component can, in the long run, influence every other.

To illustrate the DMN in action, we will use a detailed hypothetical scenario. This methodological choice allows for a clear and controlled demonstration of the framework’s mechanics, free from the idiosyncratic constraints of a single real-world platform, thereby ensuring the model’s general principles are clearly understood.

Scenario: A prominent historical institution creates a virtual exhibition on “Upheavals and Their Echoes”.

Human curators decide that the exhibition should compare the Mainland Revolution and the Colonial Uprising through key artefacts, like artworks, official papers, and everyday objects. They prepare interpretive text linking the two, highlighting themes of liberty and colonial dynamics. They also want the user to grasp a chronological sequence in each upheaval’s events. They upload 50 carefully chosen artefacts, each with descriptions that mention links between the Mainland Republic and the Island Colony, where applicable.

The institution’s website uses a personalisation algorithm that, by default, shows user items related to those they have clicked on. Additionally, there is a search function and a “trending items” sidebar that shows the most viewed artefacts. The algorithm does not inherently know about the curator’s thematic goal; it is driven by user interest metrics and content similarity; it tags each artefact with keywords.

One user, Elara, arrives and initially clicks on a famous depiction of the Seizure of the Citadel (Mainland Revolution). The algorithm then recommends other Mainland Revolution items (similar tag “Mainland” or popular items in that category). Elara follows a path through Mainland artefacts exclusively, like Citadel Keys, the Deposed Monarch’s Execution Device Component, etc. She spends a lot of time on these. The Colonial Uprising items, being less familiar, appear less in her personalised feed, except maybe a generic prompt “Explore related upheavals”, which she ignores. Many users behave similarly, so “trending” ends up mostly with Mainland artefacts.

Here, the artefact/data set was comprehensive, but the algorithm prioritised one subset due to popularity and similarity, partially undermining the curatorial schema, which intended a comparative narrative. The user Elara constructed meaning largely around the Mainland Revolution, perhaps leaving with the impression that the Colonial Uprising was a footnote or not deeply explored. The myth that could emerge unintentionally is a Mainland-centric one: the exhibition might inadvertently reinforce the notion that the Mainland Revolution is the “primary” upheaval and others are peripheral.

Recognising this, curators tweak the system. They adjust the algorithmic logic or instruct the developers to do so, so that if a user views more than three items from one upheaval, the next recommendation must be from the other upheaval, “cross-pollinate interests”. They also add a virtual prominent introduction panel every user sees first, framing the two upheavals together to set the expectation of comparison. Now, when the user explores, after a few Mainland items, she is suggested a Colonial Uprising artefact with text like “Meanwhile in the Island Colony…”. Suppose she clicks it out of curiosity—now she starts to see the intended parallel narrative. Even if she had not, the intro would plant the idea that there is another track to explore. Over time, this yields a more balanced engagement across the content.

In this scenario, the DMN framework helps identify where meaning construction was veering off the intended path (algorithm-user interaction creating an imbalance) and provides a methodology to correct it (dialectically introducing the counter-content to personalise not just for similarity but for contrast, guided by curatorial intent). It also highlights that meaning is not located in the artefacts alone or in the user’s head alone, but in the nexus of artefact-data, schema, algorithm, and user.

4.2. Principles for Critical Algorithmic Curation

The DMN’s conceptual framework translates directly into a set of practical principles for practice. These principles, outlined below, are intended to guide the concrete decision-making of curators and system designers seeking to build virtual experiences. We outline several such principles.

All actors in the nexus should be as reflexive and transparent as possible about their role in shaping meaning. For curators, this means being explicit about the themes and interpretive angles, so users and even algorithms can “know” the intended narrative. For algorithms, this means providing users with some insight into why they are seeing certain content. A platform might achieve this through a simple mouse-over tooltip on a recommended item that reads, “Shown because you expressed interest in 18th-century portraiture”, which invites users to be aware of how their experience is shaped and enables them to take a more critical stance. This counters the myth of neutrality by making the curation process more visible. For example, they might purposely click an item outside their usual interest once they realise the system is filtering their view. Transparency fosters trust as well, but importantly, it keeps the meaning-making process an open dialogue rather than a hidden orchestration.

Identify key oppositions and ensure the system presents both sides in some form. This could be through interface design (e.g., always pairing a well-known object with a thematically linked lesser-known one in recommendations), content selection (curators deliberately include artefacts that challenge the dominant narrative), or algorithmic rules (as in the revolution example, forcing cross-category suggestions). The idea is to prevent one force from completely overwhelming the narrative [

23]. If personalisation is the thesis, introduce a bit of anti-personalisation as antithesis, a random item or staff pick for all users to see. If the exhibition theme has an inherent bias, incorporate perspectives or objects that offer a counterview. By structurally embedding dialectical pairs, the museum ensures that meaning is constructed through comparison, reflection, and critical contrast, not a one-dimensional stream.

Use the multimedia and interactive capabilities of digital platforms to cater to multiple modelling systems and learning styles. A rich interpretive environment emerges from the thoughtful combination of visual, textual, and auditory information. For instance, an artefact’s page might have an image (visual primary experience), a curatorial essay (textual secondary modelling), and an audio clip of an expert dialogue or a descendant’s voice (adding narrative and personal context, a tertiary cultural perspective). Multi-modality ensures that if one channel, say, the image alone, might be misunderstood, another channel can clarify. It also invites users to engage actively, thus blending passive and active consumption. An algorithm can assist by detecting if a user is skimming quickly or if a user seems deeply engaged offer more detailed content. The goal is to sustain a rich interpretive environment where meaning can emerge from the convergence of different kinds of signs, not just a flat catalogue of pictures.

Ensure that multiple voices or perspectives are represented to combat singular myth-making. In practical terms, this might involve including commentary from various sources: curators, community members, artists, even crowd-sourced interpretations [

68]. This echoes Bakhtin’s concept of heteroglossia, a plurality of voices generating a more dialogic meaning [

69]. Algorithms can be tuned to incorporate this: e.g., highlight user comments or alternate interpretations if they are highly upvoted, not just official text. Pluralism also extends to cultural diversity. If the museum is global, the platform might allow filtering or exploring by different cultural lenses, such as what Chinese scholarship says about this painting vs. Western scholarship. The DMN thrives when users can see that meaning is not monolithic; instead, they can navigate between perspectives, which inherently teaches critical thinking and deeper understanding. If multiple interpretations are visible, it is harder for any one myth to pass off as “natural” [

70].

Encourage the user to be an active participant in curation, not just a consumer. Features like creating one’s own collection or tour, adding notes, or sharing interpretations transform the user from viewer to co-curator. Many museums have started to embrace co-curation in physical spaces [

71,

72]. The virtual space makes this even easier. Users can drag and drop to make their gallery, or there can be a “curation game” where they arrange objects to fulfil a challenge. By empowering users in this way, the museum acknowledges the validity of personal meaning-making while also potentially gathering insights into how people connect the dots. The algorithm can learn from user-created collections, which might reveal novel affinities between items that curators had not emphasised, thus enriching the overall nexus. Features that transform the user from viewer to co-curator help break the passivity Adorno warned of. It makes them aware that meaning is not simply delivered to them; they are constructing it. This principle must be balanced with guidance to avoid total chaos or overwhelming novice users. Consider how Wikipedia turned readers into editors, many platforms succeed by letting users play an active role [

73], adding a layer of folksonomy on top of curatorial taxonomy, merging formal and informal models of meaning.

The DMN implies ongoing dialogue, so a final principle for institutions is to continuously monitor and adapt. This means using analytics not just for vanity metrics, but to see where the meaning-making might be breaking down. If an important object is rarely viewed, perhaps the algorithm is not surfacing it, or users do not understand its significance. Or if users overwhelmingly interpret something in a way curators did not expect, deduced from comments or questions asked, the museum can incorporate that interpretation or clarify the context. In essence, the museum-visitor relationship becomes more conversational online. The DMN encourages responsiveness, treating the curation as an evolving process where user input is part of the curatorial thinking. This echoes the idea of the “post-museum” [

9] positioning itself as a moderator of meaning rather than a dictator of meaning.

These principles, derived from the theoretical matrix we built, act as concrete guidelines. They show how an understanding of Benjamin, Sebeok, Barthes, and Adorno can translate into actions. DMN is not a rigid template but a way of thinking about curation, one that actively seeks out tensions to leverage, voices to include, and continuous feedback loops to refine meaning delivery.

5. Philosophical Implications of the DMN: Rethinking Meaning, Authenticity, and Authority

Adopting the Dialectical Modelling Nexus framework entails a shift in how we philosophically conceive of meaning in the context of digital curation. First and foremost, it moves us away from viewing meaning as something that is transmitted (from object or curator to a passive audience) and towards meaning as something that is co-created in a dynamic system. This aligns with constructivist theories in museum studies and education, which hold that visitors construct knowledge through interaction, bringing their own context (or Umwelt) to bear [

74,

75,

76]. The DMN formalises this constructivist view in the digital realm, illustrating how various inputs like human, algorithmic, and material come together in the act of meaning-making.

While not dismissing the value of the authentic original, DMN suggests that the authenticity of experience can, in some cases, be cultivated digitally by the authenticity of context and interaction. The framework implies that the experience may be considered authentic if it sincerely engages the user in a truthful, rich dialogue with the content. For example, seeing a high-quality 3D model of an artefact along with hearing indigenous community members talk about its meaning can be, in an interpretive sense, more “authentic” than seeing the object behind glass with a dry label. Museum experience belongs to the creatures that undergo it and follows the conventions set by the museum. DMN extends this to say we can establish new digital conventions that uphold the authenticity of meaning even if the object’s physical aura is absent. Authenticity thus shifts from a property of objects to a quality of the interaction and context—an interaction that the DMN strives to make sincere (transparent, reflexive, multi-voiced, not manipulative).

This links to the question of authority and authorship. Traditionally, museums have been authoritative voices. The DMN, in promoting dialogue, inevitably decentralises authority to a degree [

77]. Like Barthes’s proclamation of the “death of the author” [

78], here, we metaphorically “de-centre” the curator as the sole author of exhibition meaning, without eliminating their role entirely [

79]. Instead, the curator becomes one voice, albeit a primary, guiding one in a conversation. The algorithm and the user are also authors in this sense. The result is a more democratised epistemology: knowledge about the artefacts is produced collectively. This does not mean relativism; curators still provide expertise and factual accuracy; the framework does not give equal weight to any and all statements regardless of truth, but it does mean the museum acknowledges that interpretive authority is shared. DMN operationalises that by building multiple narratives and power-awareness into the system itself.

One might worry that this undermines expertise or leads to fragmentation of meaning, because everyone gets their own truth. However, the dialectical aspect of DMN suggests that through the clash and resolution of perspectives, a richer, more robust understanding can emerge, where truth is not a static given but evolves through the process. In practice, this could mean visitors gain a more critical understanding; they not only learn facts about an object but also learn that interpretations can differ and why. That meta-understanding is itself a significant educational outcome, fostering critical thinking. It positions the museum more as a forum, as Duncan Cameron envisioned, “the museum as forum” rather than a temple [

36], where knowledge is negotiated.

Furthermore, embracing DMN could reposition how museums see their mission in society. If meaning in virtual museums is co-constructed, then the museum’s role is partly to facilitate constructive dialogue and ensure quality of interpretation. It is a humble stance, instead of claiming to dispense meaning, the museum cultivates an environment where meaning grows. This humility can increase trust in the long run, especially in a time when institutions are often under scrutiny to be more inclusive and transparent. It is an approach that can address criticisms of museums as colonial or elitist by structurally incorporating other voices and acknowledging past biases.

Another implication touches on the nature of the digital medium itself. By framing algorithms as part of the meaning nexus, technology is not neutral but is an active cultural participant. The DMN approach is like an STS (Science and Technology Studies)-informed museology; it insists on reflecting on the algorithm’s influence and designing it conscientiously. It thereby contributes to a broader philosophy of humane technology, technology designed for human values, not just efficiency or profit. In a world grappling with algorithmic biases and opacities, DMN offers a concrete example of how to integrate algorithms into a cultural institution in a way that is value-conscious. It stands against a deterministic or technocratic philosophy that might say, “let the algorithm decide the museum layout based on data”. Instead, it embodies a critical theory approach, always interrogating who benefits, what is said and unsaid, in any algorithmic operation.

Lastly, the DMN may have implications for how we view the longevity of meaning. Museums traditionally think in the long term, preserving objects ad perpetuum, digital content, and user-generated aspects are more ephemeral [

80]. The DMN, by combining the two, forces a contemplation of how enduring meaning is created in a fluid medium. It suggests perhaps a new notion of the living museum, one that continuously adapts and updates narratives. Meaning is not locked in vitrines or catalogues but is dynamic. Yet, because the framework is systematic, it does not devolve into complete flux; it maintains continuity through dialectic. You cannot have dialectic if everything changes at random. It changes through a reasoned process. So, one could say DMN aligns with a dialectical philosophy of history. It sees the museum as a place where history is continuously rewritten through the interplay of past and present voices. This might be the closest practical realisation of a postmodern museum ideal, not a house of stable narratives, but neither a chaotic relativism; a structured, critical discourse in perpetual development.

By embracing the DMN approach, museums in the digital age can transform what might be a liability (algorithms and remote engagement potentially diluting meaning) into an asset (a more personalised, yet critically robust, cultural experience). It is a way for museums to stay true to their public mission amid rapidly changing technology, ensuring that, however virtual or AI-driven the platform becomes, the result is still guided by humanistic values and yields genuine educational value.

6. Conclusions

The advent of algorithm-driven virtual museums forces us to confront the question of how meaning is constructed and mediated when curatorial decisions are augmented or partly taken over by complex digital systems. Existing theoretical approaches, from Benjamin’s lament of aura loss to optimistic visions of digital democratisation, and from semiotic analyses of museum communication to Adorno’s warnings of cultural commodification, each illuminate crucial aspects but on their own offer only partial guidance [

1,

35,

80]. In this paper, we have argued for an integrative solution: Dialectical Modelling Nexus that synthesises and critiques these prior theories while providing a new conceptual framework to understand and shape meaning in the algorithmic museum.

The DMN begins by acknowledging the inadequacies of any single-position solution. Instead of choosing sides (analogue authenticity vs. digital access, human expertise vs. machine personalisation, etc.), it brings these into dialogue. By doing so, it captures a more holistic picture of how meaning emerges: not from objects alone, nor from users alone, nor from algorithms alone, but from the interplay of all three within cultural and ideological contexts. This dialectical-semiotic perspective allowed us to map out how aura can be partially recontextualised, how sign networks can be preserved and expanded digitally, how new myths can be identified and countered, and how the forces of commodification can be checked by conscious design.

We then translated this theoretical model into actionable principles. We illustrated where an uncritical algorithm might undermine meaning, and how a DMN approach corrects course by re-balancing content and encouraging active interpretation. We proposed practical measures, transparency cues, diversified recommendations, multi-perspective content, and user curation tools that any museum can adapt to begin aligning their digital platforms with the DMN approach. The implementation of these ideas leads to a virtual museum experience that is at once personalised and pluralistic, intuitive and thought-provoking, dynamic and reflective.

Philosophically, the DMN reframes the museum from a presenter of truths to a mediator of dialogues, without abandoning the pursuit of knowledge or the importance of expertise. It shows that embracing interactivity and algorithmic assistance need not mean forsaking critical rigour; on the contrary, these tools, if guided by theory, can enhance critical engagement. The museum thus evolves into what might be called a critical platform, a space where visitors not only consume content but also learn about the very processes of curation, interpretation, and bias that shape that content.

Practically, we recognise that realising the full DMN is an ongoing journey. It calls for iterative design, experimentation, and a willingness to learn from audience feedback, effectively treating the digital museum as a living, learning organism. This is fitting, since the core of DMN is continuous evolution through dialectic. It is an approach that encourages self-correction and growth. Future research should focus on operationalising the framework. The DMN could be developed into a heuristic for designing new recommender systems, a UX audit tool for evaluating existing platforms, or a framework for creating evaluation metrics that measure critical engagement rather than just clicks. Such studies could empirically test the impact of DMN-aligned design on visitor understanding and explore how different audiences respond to dialectically balanced digital narratives.

Nevertheless, the practical implementation of the DMN faces significant challenges. Its success is contingent on resource allocation, as building and maintaining nuanced algorithmic systems requires expertise that may be beyond the reach of smaller institutions. It demands a departure from institutional inertia, requiring deep and sustained collaboration between curatorial, educational, and technical teams that often work in silos. Many institutions lack direct control over the algorithmic platforms they use, relying on commercial “black box” systems [

81]. In these contexts, the DMN’s value shifts from a tool for direct system design to a framework for strategic intervention and critical procurement. It empowers curators to engage in strategic content curation, writing metadata and descriptive text designed to “nudge” opaque algorithms towards more meaningful connections. It also serves as a critical rubric for policy and procurement, guiding institutions in evaluating third-party vendors on their algorithmic transparency and alignment with museological values. Furthermore, the framework’s potential is limited by the quality of the underlying data; an algorithm cannot surface counter-narratives if the collection’s metadata are sparse or reflect unexamined historical biases. These hurdles underscore that adopting the DMN is a profound strategic commitment, not a simple technical upgrade.

The DMN offers a way forward for virtual museums to navigate the complex demands of the 21st century. It accepts that technology is now an inevitable partner in curation and turns this partnership into an opportunity for innovation in meaning-making. By consciously blending aura with accessibility, scholarship with user input, and critical theory with technical design, museums can create virtual experiences that are as intellectually and emotionally resonant as the best of in-person visits, and in some respects, even more so, given the additional layers of interaction and insight available. The meaning constructed in such a setting is not a thin digital echo of the real. It is a rich tapestry woven from threads old and new, human and algorithmic, authoritative and vernacular.

What the DMN underscores is that meaning in the digital museum is not given but negotiated. And when that negotiation is guided by a dialectical-semiotic framework, the result can be a deeply rewarding cultural dialogue, one that reflects the complexity of our world and equips visitors to engage with that complexity. In an era when understanding across differences and critically navigating information are more important than ever, the museum that adopts such an approach truly fulfils its educational mission in a contemporary way, ensuring that as our tools change, our capacity to find meaning only grows richer, more inclusive, and more self-aware.