1. Introduction

The courtyard house is a widely spreading domestic typology across the Arabian Gulf region. By technical definition, a courtyard, or what is known as “hawsh” or “hawy” in local parlances, refers to the open area in a house enclosed by walls or adjacent buildings. It is surrounded by rooms on its perimeter while forming an open-air core. In vernacular courtyard houses, factors such as Islamic and social principles, the environment–behavior interactions of the dwellers, the climatic effect, security concerns, and the available technology and building materials altogether have influences on determining the form and function of a courtyard house [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. These influences lead to homogeneity and harmony in the overall fabric of old cities and settlements.

The article explores the typology of courtyard houses in the Gulf region by proposing an innovative methodology based on visibility graph analysis. This approach employs modeling connectivity and visibility maps to examine the selected case studies, which constitute pilot research for the application of visibility graph analysis to courtyard houses in the Gulf region. Here, a question arises about how to situate the inquiry within the fields of space syntax and computational architectural studies, thus providing a thoughtful remark in comprehending the genesis of architectural and urban development of the Gulf region’s courtyard house.

The research question has a foundational basis in the proposition that assumes the spatial form of the courtyard house to inscribe cultural and social attributes, which pertain to theories of house form and culture. Such socio-cultural factors include, but are not limited to, privacy, gender segregation, and hospitality [

6,

7,

8]. Specifically, Rapoport [

3] conceptualizes the house as a “social unit of space” and a “human fact,” where the house has the purpose of enveloping the occupant’s way of life and facilitating human culture [

3]. Hanson [

9] uses a qualitative analysis of house plans to show that similar domestic spatial arrangements reflect the unique lifestyles of the inhabitants and further relate to household organization and social life [

9]. This study, therefore, refers to these two established theoretical approaches in studying the spatiality of vernacular courtyard houses in the Gulf.

In providing appropriate answers to the research question, this paper utilizes human behavior and visibility analysis using qualitative and modeling methods. In general, three objectives emerge as defining guidelines in the process of finding answers: to document a sample of vernacular courtyard houses through reviewing the literature and the existing body of knowledge in regional scholarly work; to conduct a visibility graph analysis (abbreviated VGA) on a sample of courtyard houses using computer modeling; and to cross-check the spatiality of these houses in line with the previous research on the cultural heritage framework for preserving vernacular domestic architecture as a validation step.

Methodologically, this research provides a pilot study. It presents a sample of courtyard houses from the Gulf, specifically a case from each of six countries, including Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Referring to their architectural data aided by computer modeling, the VGA analysis of these houses uncovers the similarities or differences in space arrangement, functional uses, system of activities, and attributed lifestyles of the inhabitants. The final achievement would be proof (or disproof) of the existence of common spatial patterns in the courtyards as a matter of space visibility and connectivity across the selected courtyard houses.

These findings confirm that the spatial form of the courtyard house relates mainly to the socio-cultural factors and the occupants’ system of activities, representing an organic, sustainable linkage between architecture and society. Given the historical background of this study, architects and urban designers can draw various lessons from vernacular architecture and integrate these lessons into contemporary and future studies of regional domestic forms in a way that fosters architectural sustainability.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Spatial Culture of Courtyard Houses

The courtyard house is one of the most ancient forms of dwelling in the world [

10,

11,

12]. Its evolution is seen as a response to socio-cultural and environmental necessities. In this regard, Petruccioli [

4] describes the typological processes inherent in the courtyard house’s development in Middle Eastern cities, where he questions the universality of the courtyard house as an archetype far from regional variances. Regionally, the inland Arab settlements consisted of tents that enclosed a common central core as a way to achieve security and endurance from desert climatic conditions [

13]. Thus, the open space in the courtyard house was the result of a series of historical urban transformations responding to a set of daily life socio-cultural, environmental, and economic necessities [

5,

14,

15].

The courtyard house represents a contrast of solid and void and prioritizes inward-looking over outward-looking (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The open-air interior versus the thick-walled exterior responds to the veiled, introverted characteristics of vernacular Islamic architecture shaped by the need for privacy. The interior of the courtyard house is the focus of attention, as it symbolically represents status and identity. On the other hand, the exterior of the courtyard house represents homogeneity and harmony in blending with the social context to establish a collective identity [

16].

There are a number of significant factors in determining the spatial form of a courtyard house, namely (i) privacy, (ii) gender segregation, (iii) hospitality, in addition to (iv) security, and (v) protection from the harsh climate [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. These socio-cultural factors are part of the Arab–Muslim culture, where privacy is a prominent social and cultural parameter. Privacy has a great influence on the formative aspect of courtyard houses and their spatiality [

20,

21,

22]. Personal space and privacy are essential to maintain within the household, where privacy hierarchically ranges from internal privacy between members of the same household to external privacy from neighbors’ dwellings and the public sphere [

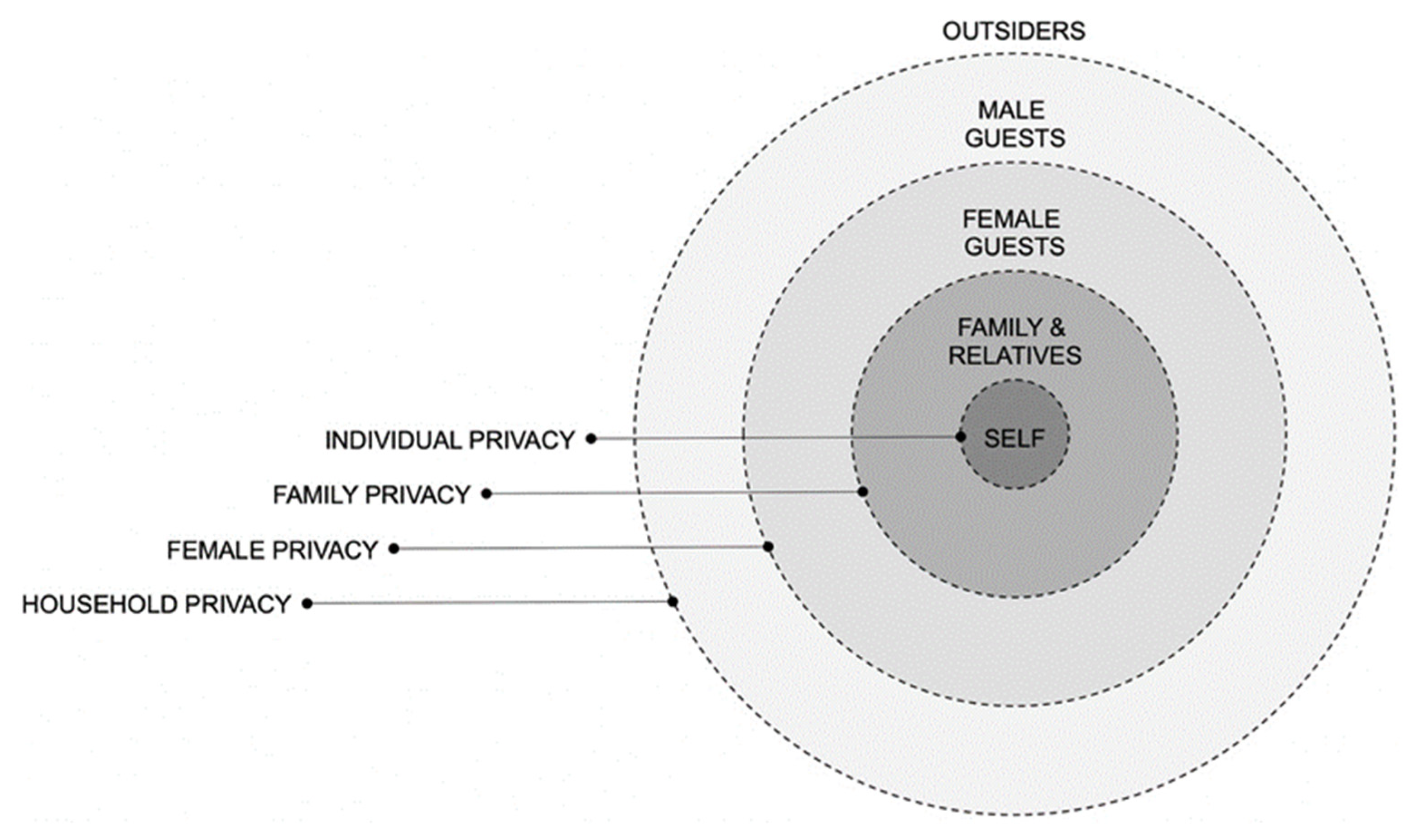

23]. The hierarchical priority of privacy centers on the individual, followed by the privacy of the family, female guests, male guests, and then outsiders in a successive order (

Figure 3). To clarify, family privacy relates to the occupants that belong to the same affinity, while household or dwelling privacy relates to the unit of the house holistically, accounting for other dwellers such as servants or domestic assistants in addition to male visitors.

Another influential socio-cultural pattern in the spatial form of Muslim houses is gendered spatial segregation [

24,

25]. It refers to the separation or the isolation of spaces between male and female users, rooted in the historical zonal subdivisions of “haremlik” and “selamlik” [

26,

27]. Accordingly, the haremlik is a private section of the household with spaces for family members, such as living areas and female quarters. In contrast, the selamlik is a spatial area designated for male visitors and guests. Elwerfalli [

27] clarifies that such spatial subdivisions could be either horizontal, meaning that in larger houses the selamlik spaces are allocated in close proximity to the main entrances into the public street, and the haremlik spaces are deeply integrated into the household. In smaller dwellings, the separation could take a vertical order, with the selamlik occupying ground levels while reserving upper floor levels for the haremlik [

27].

Similarly, hospitality is an essential attribute of the Arab culture in pre-Islamic Arabia. Islam further approves it as an ethical value and a unifying attribute in the Muslim community [

13,

28]. Consequently, hospitality reconnects the individual to the communal. In early settlements of tents and traditional houses, hospitality results in the development of spaces for visitors and guests, such as majlis rooms and reception quarters (

Figure 4). Until today, hospitality spaces in contemporary houses have taken various spatial and formative schemes to maintain an essential socio-cultural factor of the practiced culture.

In arid regions with a similar climatic influence to that of the Arabian Gulf, according to Bekleyen and Dalkiliç [

29], courtyard houses establish strict privatization of space and introversion seen in the separation of functions into spaces assigned to public or private uses. Different interpretations of religious norms, economic conditions, identity guidelines, or socio-cultural determinants lead to varying levels of socio-cultural patterns in varying contextual parameters. These differences result in the wide array of courtyard house models and forms in Muslim cities, which enriches the urban history as well as proving that architecture is dependent on local imperatives [

30,

31,

32].

2.2. Courtyard Houses in the Gulf: Physical and Social Aspects

In the Gulf, courtyard houses have been the subject of a considerable body of academic research and analysis. These range from vernacular documentation to the examination of sustainable facets of regional architecture. In this context, AlKubaisy [

33] addresses the significance of the courtyard house design in the Arab region and specifically in Bahrain. He discusses the design and the layout of traditional houses in Bahrain’s old towns and settlements. In line with his analysis, the courtyard is useful in mitigating or overcoming the environmental challenges of the hot-arid regions. Spatially and socially, courtyards in houses reduce the circulation space and provide safer nodes for gatherings. Accordingly, this study refers to significant driving factors in the design of courtyard houses, including privacy and climatic factors, in addition to land utilization and saving plot area [

33].

Likewise, Aljawder and El-Wakeel [

34] present a courtyard house as a case study to illustrate the performance of daylighting devices in the same climatic conditions (

Figure 5). Part of this study summarizes the characteristics of the courtyard, including its dimensions, spatial allocation within the house, and its major objective as a climatic moderation component of the domestic unit [

34]. The same house has been rehabilitated to become the House of Bahrain Press Heritage (bait al sahafi) in an effort to maintain its cultural heritage as well as to ensure its usage by the community (

Figure 5). The main value of the house, according to Sirriyeh, is being a courtyard house type in addition to other architectural and cultural values [

35].

In his attempt to compare vernacular to contemporary domestic architecture, Al-Haroun [

19] extensively analyzes the evolution of the Kuwaiti courtyard house. He provides a thorough answer to “Why study courtyards?” clarifying that the courtyard is a vehicle for understanding socio-cultural, economic, and political transformations from vernacular to modern domestic models [

19]. The aim is to identify the qualities of vernacular elements, such as the courtyard, to adapt them in contemporary schemes (

Figure 6). This study utilizes various mixed methods, including participatory design, workshops, cognitive mapping, and questionnaires as quantitative methods, in addition to other effective tools. Haroun’s thesis is based on prior academic contributions of Huda Al-Bahar and others. Al-Bahar is a pioneer architect who recorded an intensive analysis of housing transformation in Kuwaiti traditional architecture, where she defines the courtyard as an important element in the social life of the family [

36,

37]. Al-Bahar explains that the courtyard in traditional Kuwaiti houses provides an open, dynamic, private, and protective living setting. She considers the courtyard an important element that played vital social and environmental roles.

Another contribution evaluates the role of domestic courtyard spaces from a socio-religious point of view in Oman [

38]. Courtyard typologies in Oman differ in spatial organization based on geography, resulting in four classifications of courtyard houses: (i) mountainous, (ii) desert, (iii) coastal, and (iv) southern (Dhofar region) courtyard houses. First, mountainous or oasis courtyard houses have certain features, such as subtly articulated courtyards or deconstructive courtyards due to the compact and vertical arrangement of the dwelling units [

38,

39]. Courtyards in oasis dwellings are on upper floors and act as interconnecting spaces while secluding and privatizing the system of activities. Second, on the other hand, the courtyard in a desert dwelling has a clustering character with multiple courts serving multiple functions. These clustering courts connect and link by passageways to achieve protection from climatic conditions, in addition to privacy regulation. Third, coastal dwellings spread across the small coastal region of Oman with “tunnel-like connecting courtyards to catch sea breeze causing cross ventilation” [

38]. Last, (iv) southern courtyard houses have wide courtyards as backyards to facilitate wind flow in humid conditions and high fencing walls to maintain dwelling privacy. The analysis of these typologies reveals the importance of privacy, efficiency, environmental coexistence, and the systematic code of life [

38].

Research from Qatar quantifies and analyzes vernacular architecture and the indigenous passive techniques used in courtyard houses to restore thermal comfort as a means to climatically mitigate heat during summer days [

40]. Such techniques affect the spatial form and the physical layout of buildings. In the past, courtyard houses within compact neighborhoods (furjan, plural of the singular fereej) shared thick mud walls, resulting in mutual shade and improved thermal comfort within the interior space. The interior space, however, surrounded an open-air courtyard (hawsh) that resembled the core of the housing unit, both physically and socially [

17,

41].

The spatial form of a courtyard house relates to social patterns of privacy and gender segregation in precise ways in terms of household entries, the ratio of the courtyard, and its form. Socio-cultural patterns identify with the location of rooms, the arrangement of spaces, proxemics, and other spatial configurations [

41,

42]. In addition to that, hospitality is the spatial existence of preserved areas for visitors and guests within the household, which is common in the Gulf. Spaces for hospitality include the majlis unit that is spatially located in close proximity to the main entries of households to ensure direct, undisturbed access for guests (

Figure 7). Majlis rooms were not large spaces in the past because of structural limitations of the danchal or chandal beams that supported the roof of the rooms in courtyard houses, which had a maximum width of 2–4 m. Instead, they were small, secure, and humble spaces with modest decoration to present the generosity of the household owners and to provide visitors with adequate spaces within the existing formal and financial limits [

13,

22].

2.3. Space Syntax in Domestic Settings

The theory of space syntax enables architects and urban designers to examine socio-cultural relationships in the built environment as well as in the broader urban system [

9,

43,

44,

45,

46]. In their study of the spatial reasoning for the programming of socio-spatial parametric grammar, Al-Jokhadar and Jabi [

47] utilize the state-of-the-art computational models of shape grammar and syntactical analysis to explore the social dynamics of vernacular houses. Referring to their application of space syntax analysis to investigate home cultures, the researchers deploy three computational tools in space syntax theory, namely (i) Agraph, (ii) Syntax2D, and (iii) DepthmapX. Among these three tools, the last tool is of interest to this current research endeavor in using visibility graph analysis (VGA) to model connectivity and to represent social realities in a selected sample of courtyard houses in the Gulf [

48,

49]. This study delivers a rich source of updated methods and techniques to carry out syntactic analysis in various residential typologies [

47].

Khattab [

50] adopts a similar method in his attempt to analyze traditional Kuwaiti houses socio-spatially. He proposes an analytical model that consists of (i) a space system definition, (ii) space representation as either permeability maps or axial maps, and (iii) a space system analysis in terms of syntactic relations. Later, the researcher compares the analytical models of the selected sample, or the seven courtyard houses, to establish a common spatial system of the Kuwaiti courtyard house for heritage documentation purposes.

Another study shows that the spatial and cultural features of contemporary residential villas in Qatar imply links to gender roles, hospitality, and privacy to a considerable degree [

7]. Contemporary residential villas have complicated arrangements with the street and within the indoor and outdoor areas. This happens despite the fact that the villa’s shape and spatial arrangement adhere to a standardized form and construction. The findings of the investigation seem to disprove any theory regarding the disappearance of socio-cultural functions in the spatial design of Qatari houses. Rather, they are designed to capture the essence of privacy, gendered spaces, and the hospitality culture through physical, architectural, and configurational planning [

51].

In the associated publication of the international research endeavour of ‘Gulf Sustainable Urbanism’ [

52], socio-spatial analysis is an important part of the analytical parameters in the documentation of the vernacular architectural buildings of the region. This socio-spatial study includes the maximum visual step depth, integration, and justified permeability graph analysis of selected buildings, supported by graphical representations and illustrative layouts.

To conclude, socio-spatial analysis in the domestic setting, particularly in courtyard houses of the Gulf, is a deliberated theoretical theme with contributions from researchers and scholars in the fields of architecture and urban design. There is a rising need to address this topic in the context of the Gulf as a promising approach to interrelating both sociology and architecture, prioritizing sustainability as a goal for the benefit of people and the built environment.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methods of Data Collection

The six courtyard houses were selected based on a literature review process that consists of scoping, planning, identification, searching, and screening [

53]. A literature review was used as a method and a process, where it eased the process of collecting the required sample of courtyard houses while allowing for a deeper understanding of each case’s circumstances and special features. The literature review included books, journal articles, theses, and online sources.

With reference to the literature review, this study explored the six courtyard houses in a cumulative approach, using common knowledge about traditional architecture in the Gulf to understand the spatial configuration of these vernacular houses. This approach was useful in analyzing the effect of socio-cultural aspects on the process of house formation.

The courtyard houses were selected in a consistent manner, considering various factors such as their construction date, size, location, cultural significance, and the availability of floor plans, graphical references, photographic documentation, and descriptive information about each of the courtyard houses used in this study. The most important factors that determined the selection of the houses were their floor plans’ clarity and readability, and the presence in each of a courtyard with clear dimensions and form to allow for a reliable spatial analysis. To clarify further, the principles used in selecting the courtyard houses were guided by the following specific criteria:

The houses were built during the period 1850–1950:

The houses belonged to the traditional phase, or the pre-oil phase, of urban growth in the Gulf city [

54]. During this period, the housing practices of the indigenous communities were evident in the way they built their houses in compact neighborhoods. The construction of houses was characterized by the use of locally sourced building materials and simple building techniques. Another characteristic was the sea-oriented settlement pattern of the courtyard houses along the shorelines of major cities and towns.

The size of the courtyard houses ranged from 200 to 600 square meters:

The footprint area of the building corresponded to the area of the ground floor level in courtyard houses. It is important to note that courtyard houses within this range of floor area were considered medium-sized family dwellings and the typical residences of ordinary citizens, which closely resembled the common characteristics of domestic architecture.

The geographical location (the courtyard houses were located in coastal cities):

The geographical location had a direct effect on the design and construction of the housing unit and the characteristics of its courtyard, whether it be in coastal, mountainous, or desert locations. Meanwhile, considering the limited scope of this study, the authors tried to select cases from coastal locations as a unifying condition for courtyard house selection in Gulf cities.

The houses were selected based on their cultural significance and value:

These houses, some of which have been preserved specifically for the purpose of documenting their cultural heritage, while others have been restored and repurposed as community centers or museums, illustrate the rich building traditions and architectural legacy of the pre-oil period in Qatar and the wider region [

52].

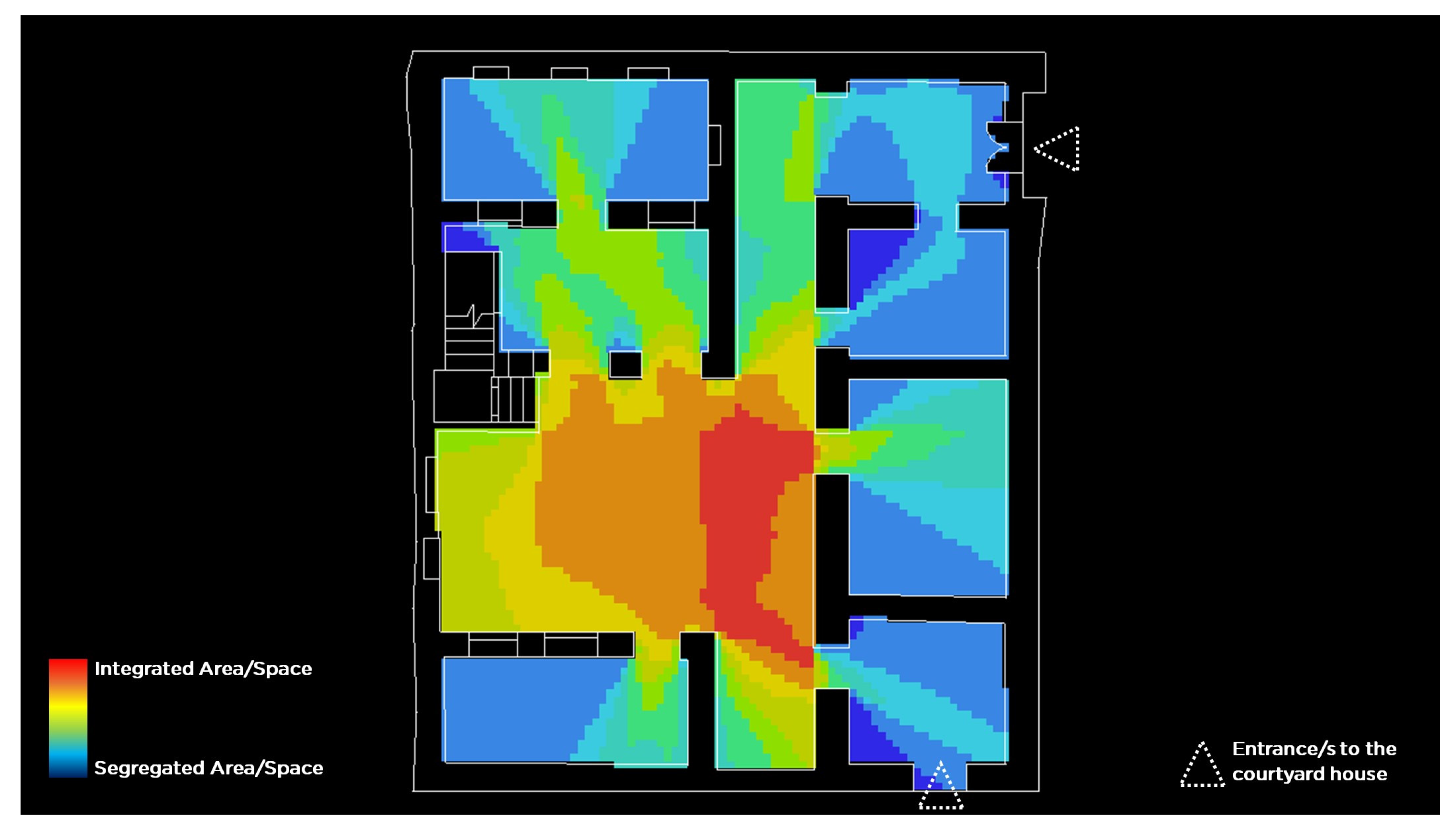

3.2. Method of Data Analysis and Applied Methodology: Space Syntax

This study used space syntax and the open-source software program, namely Depthmap0.5x. The software provided an objective description of spatial configuration in architectural drawings of buildings at various scales [

9,

14,

48,

55,

56,

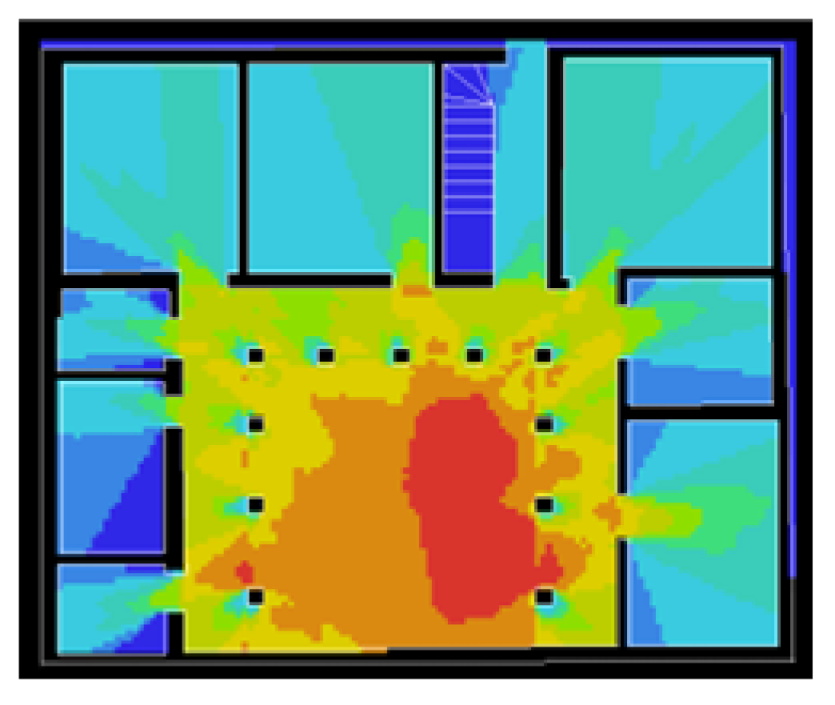

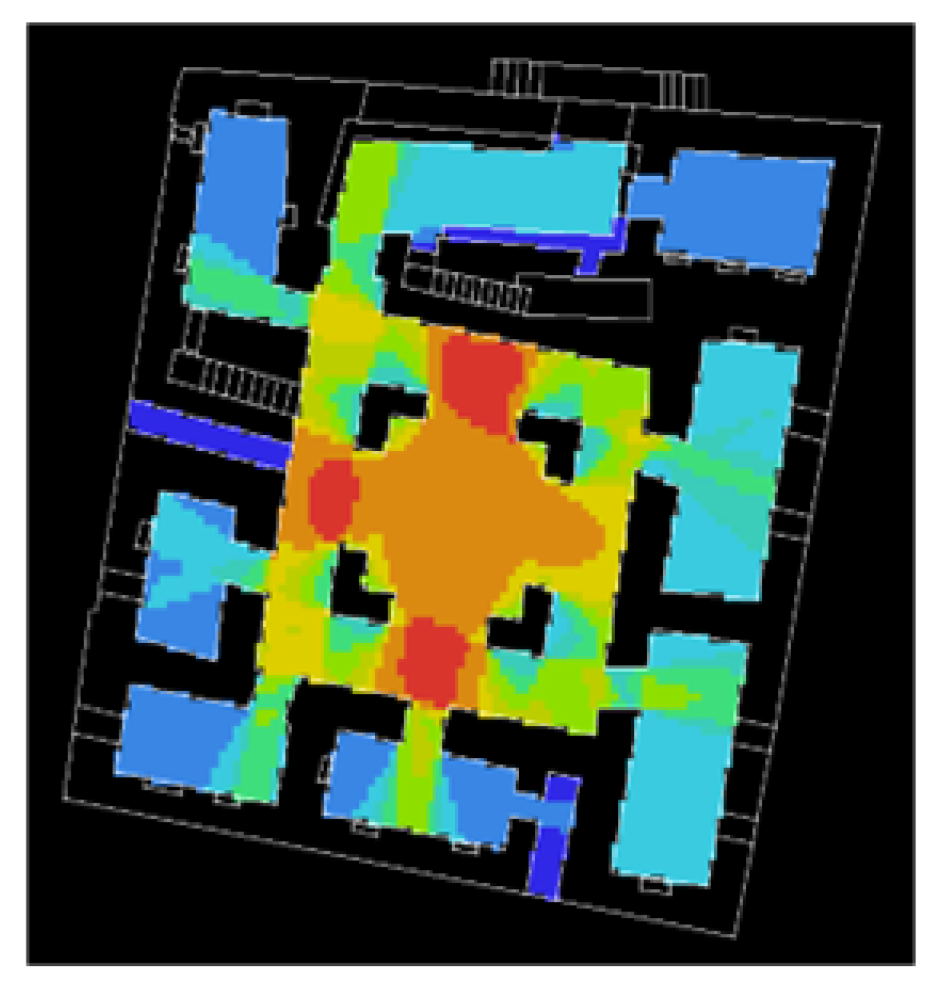

57]. The results of modeling were color-coded visibility graphs of each courtyard house. The color code included a spectrum of colors from red to blue. Red corresponded to the maximum connectivity pattern, while blue referred to less connectivity in space. The colors in between resembled intermediate connectivity and visibility patterns. To clarify, the output of this research study was visualization and modeling due to the following explanations:

This study involved visual representations of visibility analysis of courtyard houses to investigate the inscription of socio-cultural influences in the housing spatial form.

The visibility graph analysis (VGA) tool examined the reflection of light in space. The output created visibility connections between all the spaces in the studied houses using the designated software of Depthmap0.5x.

The outputs were the visually modeled maps/layout plans of the houses with color-coded schemes that represented the connectivity and visibility of spaces via a spectrum of colors from red to blue.

These visual outputs were useful in evaluating the hierarchical arrangement of public and private spaces and the inscription of the cultural influences on the housing form.

The authors modeled the selected courtyard house plans. The purpose was to illustrate the visibility performance of the central space to distinguish areas for family use from other hospitality or service spaces, such as majlis rooms and private rooms. In addition, the authors limited the analysis to ground floor levels, including the courtyard. Although the ideal case would be to analyze the entire built-up area, including the various floor levels and rooftops, if these spaces were available, because some houses in specific geographical locations of the Gulf were multi-leveled and extended vertically.

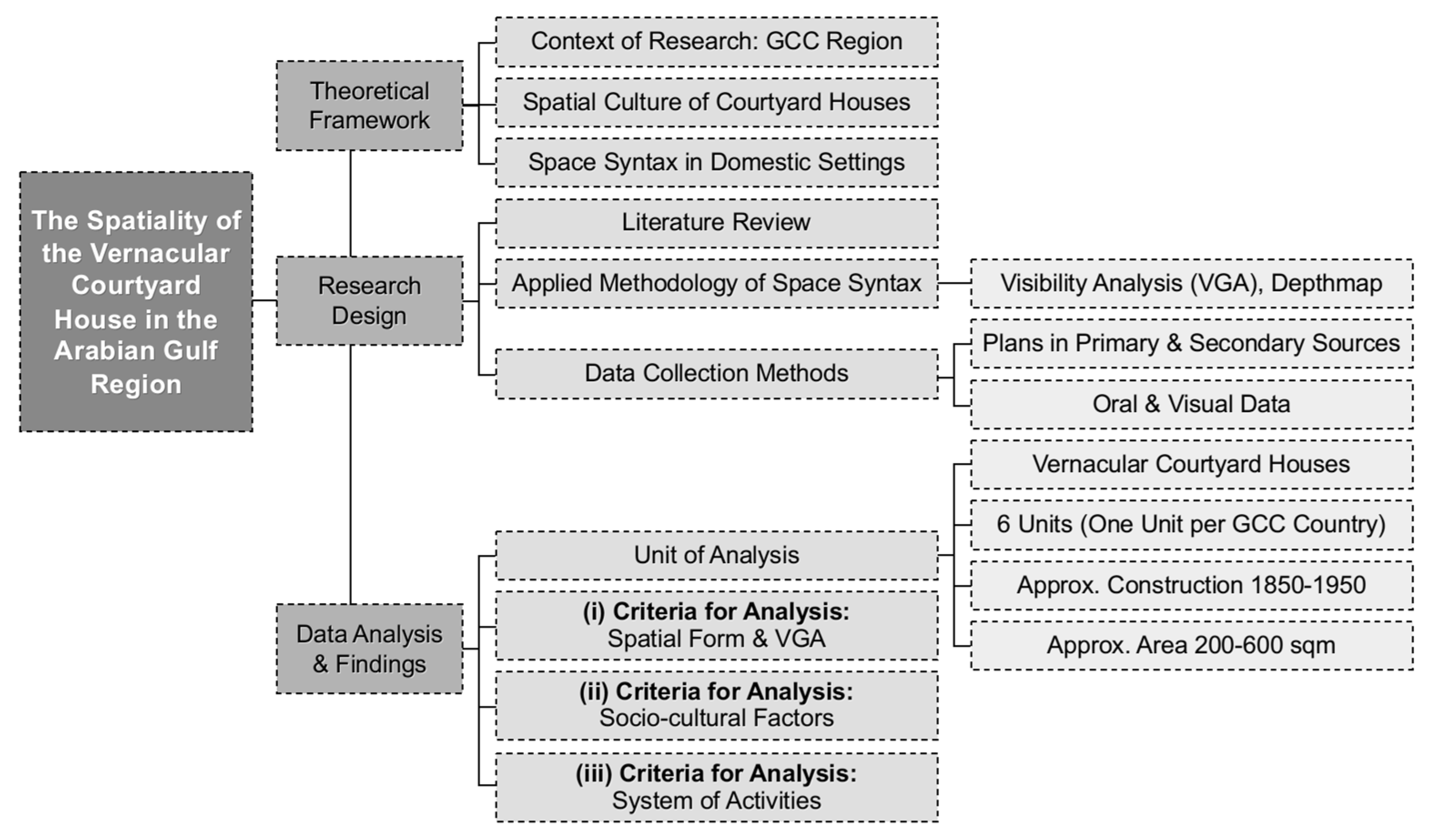

The figure below summarizes the overall research methodology of this study. It illustrates the theoretical framework, the research design, and the methods of data analysis and findings (

Figure 8).

The next section of this study brings with it the results that are divided into two subsections, namely Data Collection and Data Analysis. The Data Collection subsection presents the six courtyard houses, their references, special architectural features such as the entrances, transitional spaces, liwan spaces, rooms, and guest rooms, and the courtyards. It also presents the ground floor plans of each house. The Data Analysis subsection presents the visibility graph analysis of the courtyard houses and the connectivity performance analysis of the courtyards as a result of modeling in Depthmap0.5x software.

4. Results

4.1. Data Collection

The data collected for each house covers its city/country, approximate date of construction, approximate area, and other special architectural features of the house.

- 1.

Courtyard House Name: Sh. Abdullah Bin Mohammed House

City/Country: Muharraq, Bahrain

Approx. Date of Const.: 1880

Approx. Area (sqm): 282 sqm

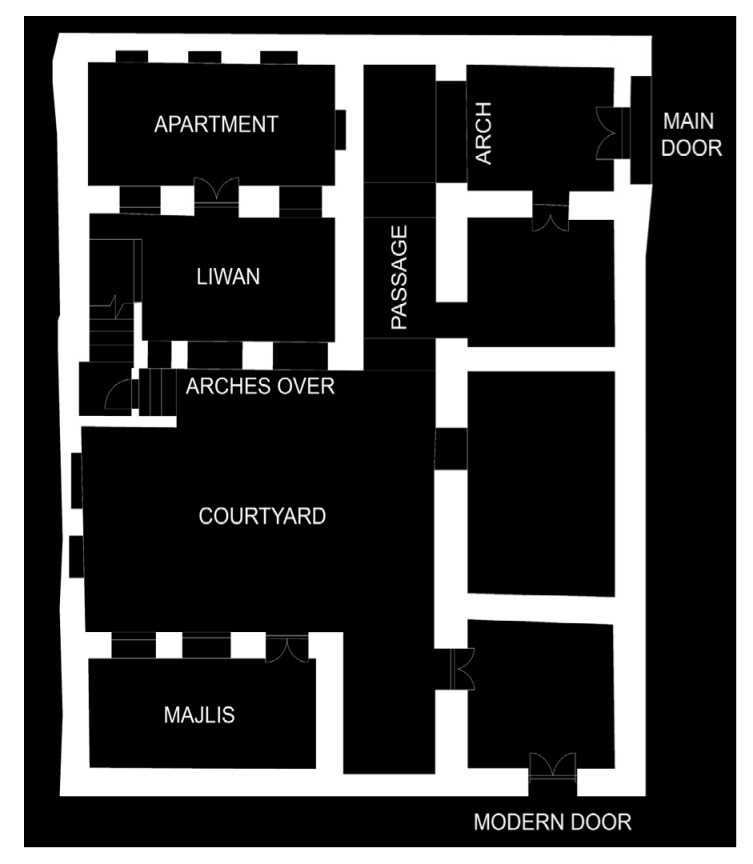

Special Architectural Features: The main entrance to the courtyard is through a doorway and an L-shaped passage from which the courtyard connects in its corner. The living room is behind a two-bay liwan. A staircase leads to the roof terrace. The majlis room opens directly into the main courtyard (

Figure 9) [

58].

- 2.

Courtyard House Name: Behbehani House

City/Country: Kuwait, Kuwait

Approx. Date of Const.: 1940

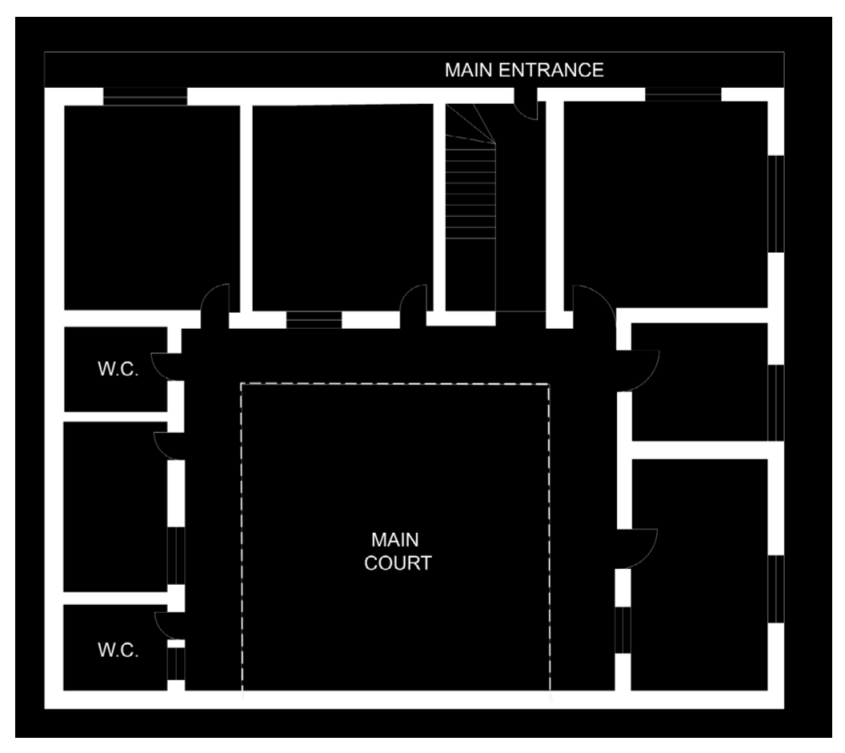

Approx. Area (sqm): 220 sqm

Special Architectural Features: The house is located in the Al-Watia area. The house is part of a larger compound that represents a traditional coastal type of domestic architecture. Its main entrance connects to the courtyard through a passageway. There are six rooms that surround the main court in addition to other service spaces (

Figure 10) [

50,

59].

- 3.

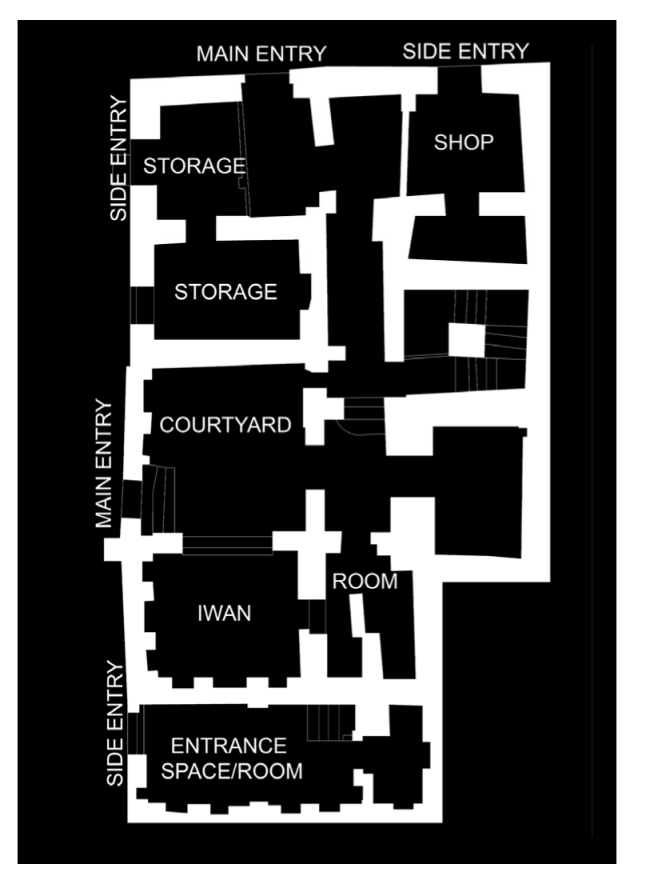

Courtyard House Name: Nadir House

City/Country: Muscat, Oman

Approx. Date of Const.: App. 1850

Approx. Area (sqm): 270 sqm

Special Architectural Features: The house is part of a residential complex in old Muscat (close to its shoreline) with an arcaded courtyard. The main gate leads to a large foyer that connects to a guest room and a staircase. The ground floor has kitchens, servant spaces, and support spaces for the house. The second floor has rooms that surround a gallery encircling the central court. The rooftop has a majlis space (

Figure 11) [

52].

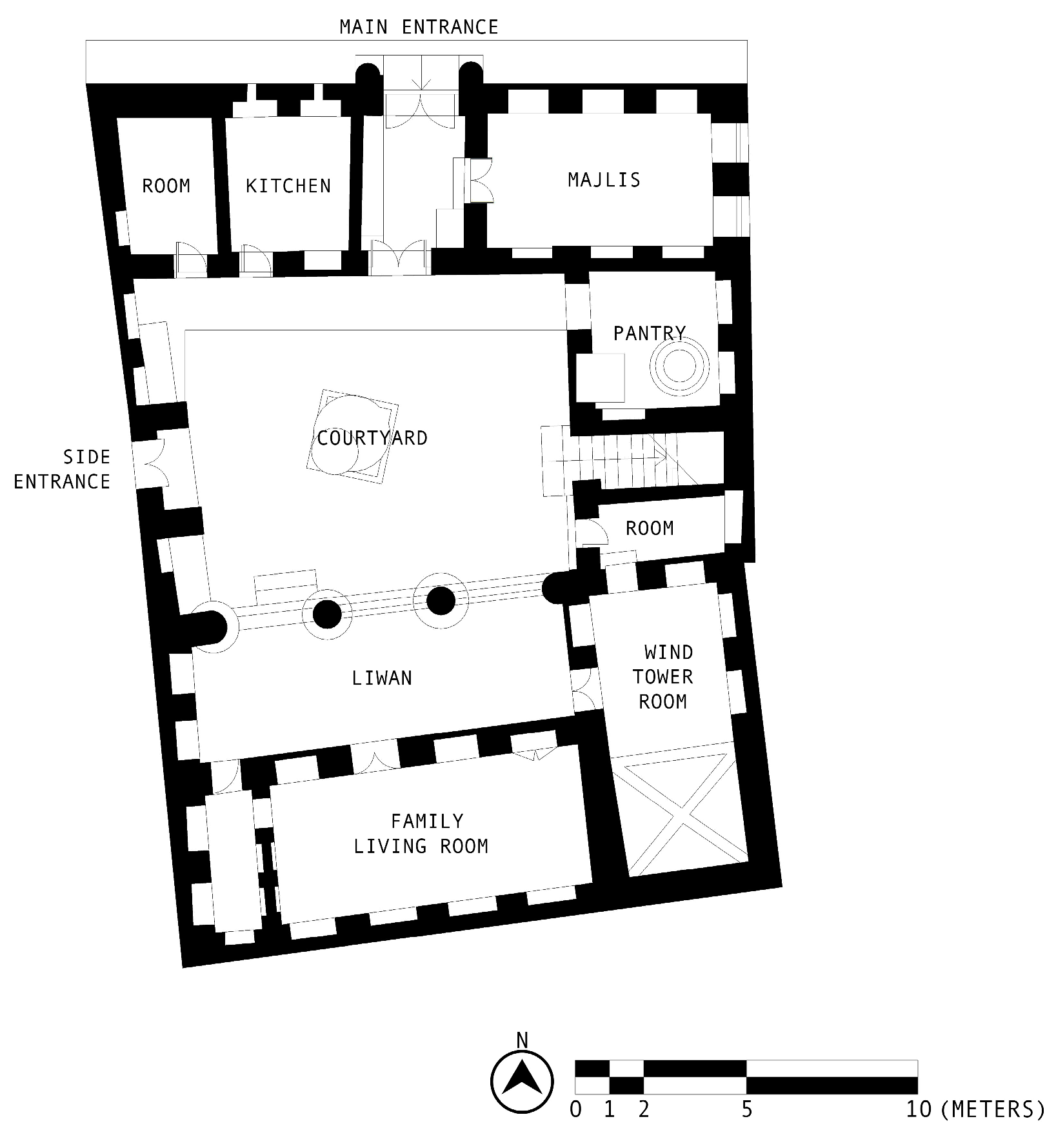

- 4.

Courtyard House Name: Mohammed Saeed Nasrallah House

City/Country: Doha, Qatar

Approx. Date of Const.: 1920

Approx. Area (sqm): 567 sqm

Special Architectural Features: The house is in Barahat Al-Jufairi of the old souq in Doha, Qatar. The ground floor has eleven rooms around the central court. The main entrance, and the only one, is on the southeastern corner, next to the majlis room. The house has a distinctive feature of the wind tower in addition to its special courtyard (

Figure 12) [

17].

- 5.

Courtyard House Name: Al-Nawar House

City/Country: Jeddah, KSA

Approx. Date of Const.: 1870

Approx. Area (sqm): 290 sqm

Special Architectural Features: The house is located in the southern central part of Old Jeddah, namely Al-Balad. It consists of two main parts (north/south) and a connecting staircase and annex rooms, arranged around a central courtyard (compact quadrangular courtyard). On the ground level, there are storage and entrance spaces, in addition to a liwan (

Figure 13) [

60].

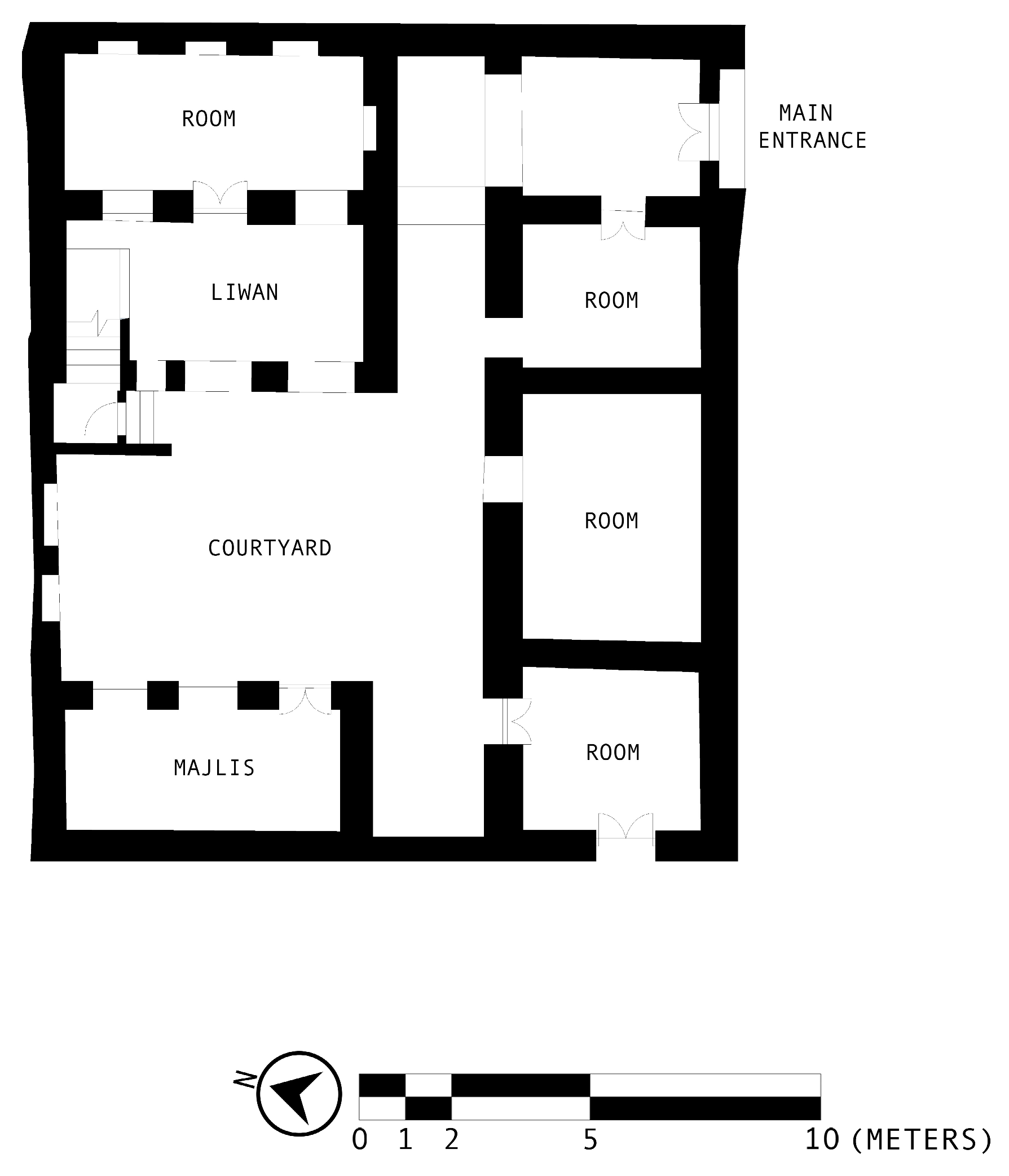

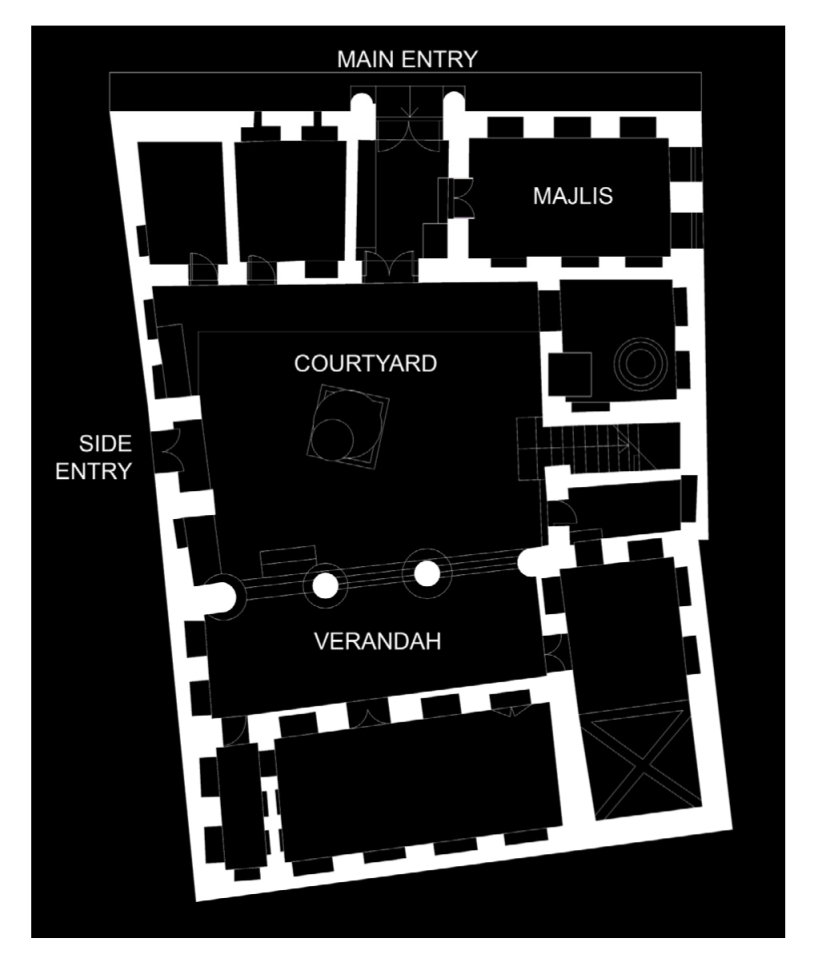

- 6.

Courtyard House Name: Abdul Qadr Rashidi House

City/Country: Dubai, UAE

Approx. Date of Const.: 1936

Approx. Area (sqm): 460 sqm

Special Architectural Features: The house is in the Al-Bastakiyyah district. The main entrance to the house is from the north under a projecting wooden balcony. There is a majlis room to the left of the main entrance. The courtyard has a raised liwan, where a large family living room is situated behind it. A side entrance opens directly into the courtyard on the western elevation (

Figure 14) [

52].

As a general observation of the data collection, the special architectural features of the courtyard houses include their location in traditional towns or neighborhoods that are still valued in Gulf cities. The existence of a courtyard is a prevailing feature of the medium-sized dwellings, in addition to a clear emphasis on entries and main doors. The courtyard houses have rectangular or quadrilateral forms that are mostly organic because of the building techniques and the limits of the construction materials, in addition to the flexibility of these forms for growth and expansion.

4.2. Data Analysis

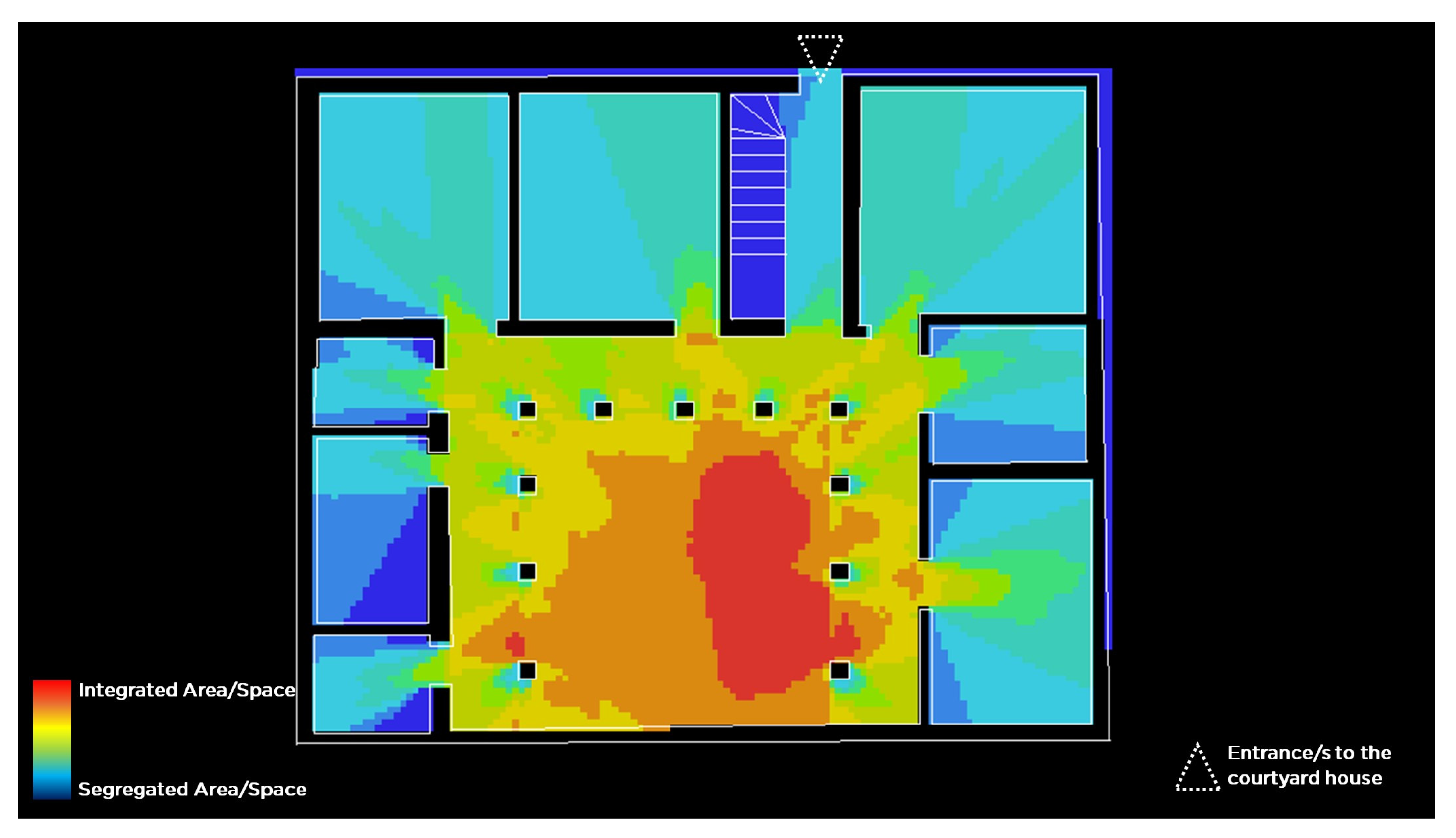

The data analysis is based on visibility graph analysis (VGA) using Depthmap software. The output is the visually modeled maps/layout plans of the houses with color-coded schemes that represent the connectivity and visibility of spaces as clarified earlier in the methods section (red = highly integrated and visible area or space, followed by orange, yellow, green, light blue, and then dark blue = highly segregated and private area or space). A brief remark on connectivity performance sheds light on the most noticeable trends with an emphasis on courtyard visibility.

- 1.

Courtyard House Name: Sh. Abdullah Bin Mohammed House

Connectivity Performance Analysis: The side of the courtyard that links to the main entrance passageway is the most connected space. Intermediate visibility patterns occur in the passageway and the liwan, signifying their transitional uses. The rest of the rooms that surround the courtyard are low in connectivity, including the majlis room and the living room (

Figure 15).

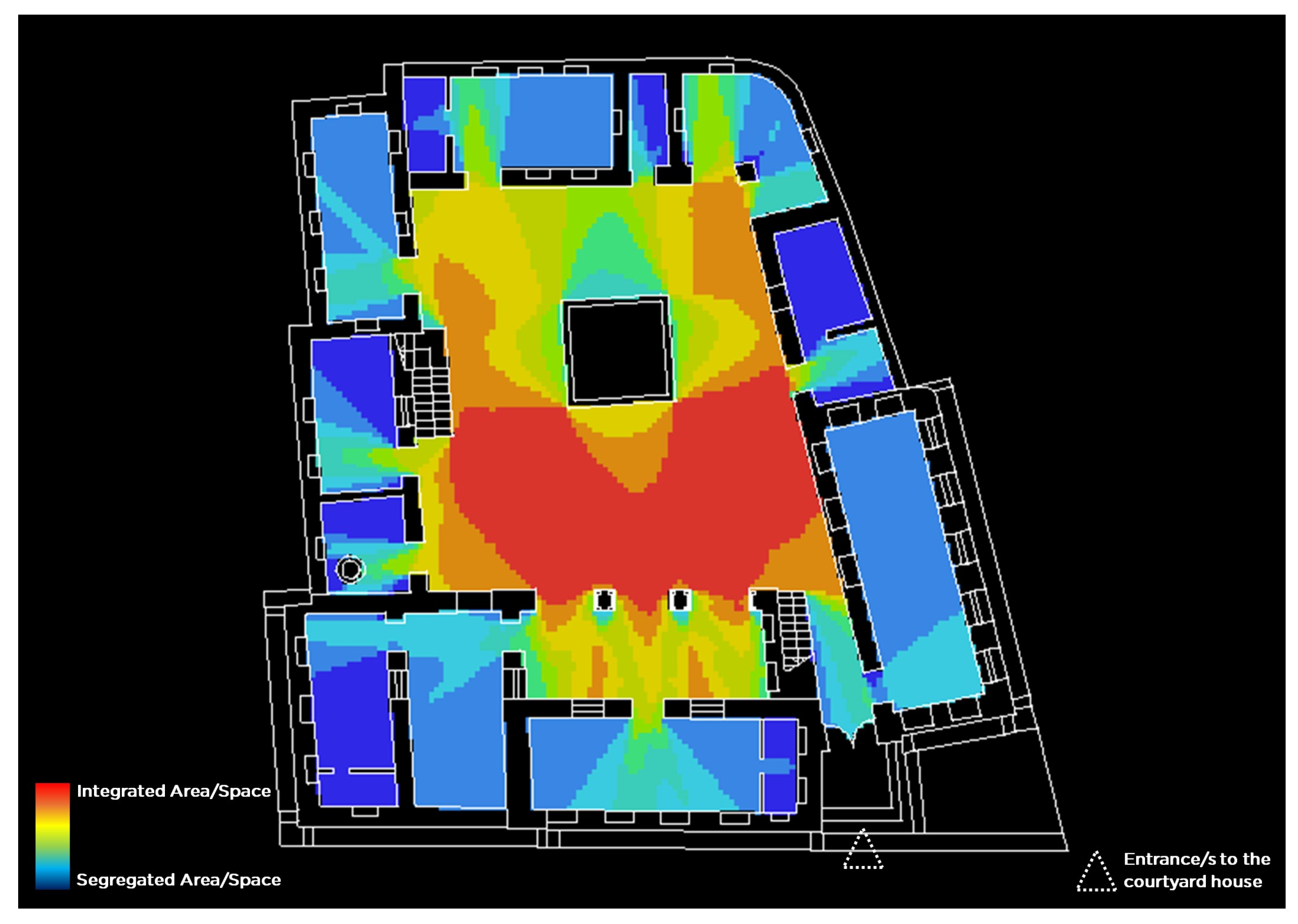

- 2.

Courtyard House Name: Behbehani House

Connectivity Performance Analysis: The U-shaped courtyard opens into the surrounding rooms and spaces. Within the courtyard, connectivity ranges from red to orange, demonstrating the highest visibility performance. The courtyard links to the main entrance through a passageway with a low connectivity pattern. All the remaining eight rooms are private and low in visibility (

Figure 16).

- 3.

Courtyard House Name: Nadir House

Connectivity Performance Analysis: The main gate opens into a foyer or lobby that is private and secluded, which connects to a private guest reception room. The courtyard illustrates high connectivity patterns around its massive corners, while connectivity gradually reduces in the intermediate spaces of a square shape. Given the nature of the rooms surrounding the main court, most of them are low in connectivity (

Figure 17).

- 4.

Courtyard House Name: Mohammed Saeed Nasrallah House

Connectivity Performance Analysis: The spacious central courtyard is high in connectivity, thus low in privacy. The main entrance connects to the courtyard through a passageway that is intermediate to low in connectivity, while it also connects to the private and secluded majlis room. In front of the sitting room, there is a liwan with an intermediate connectivity pattern, reflecting its architectural and functional usage as a semi-open space in the courtyard house (

Figure 18).

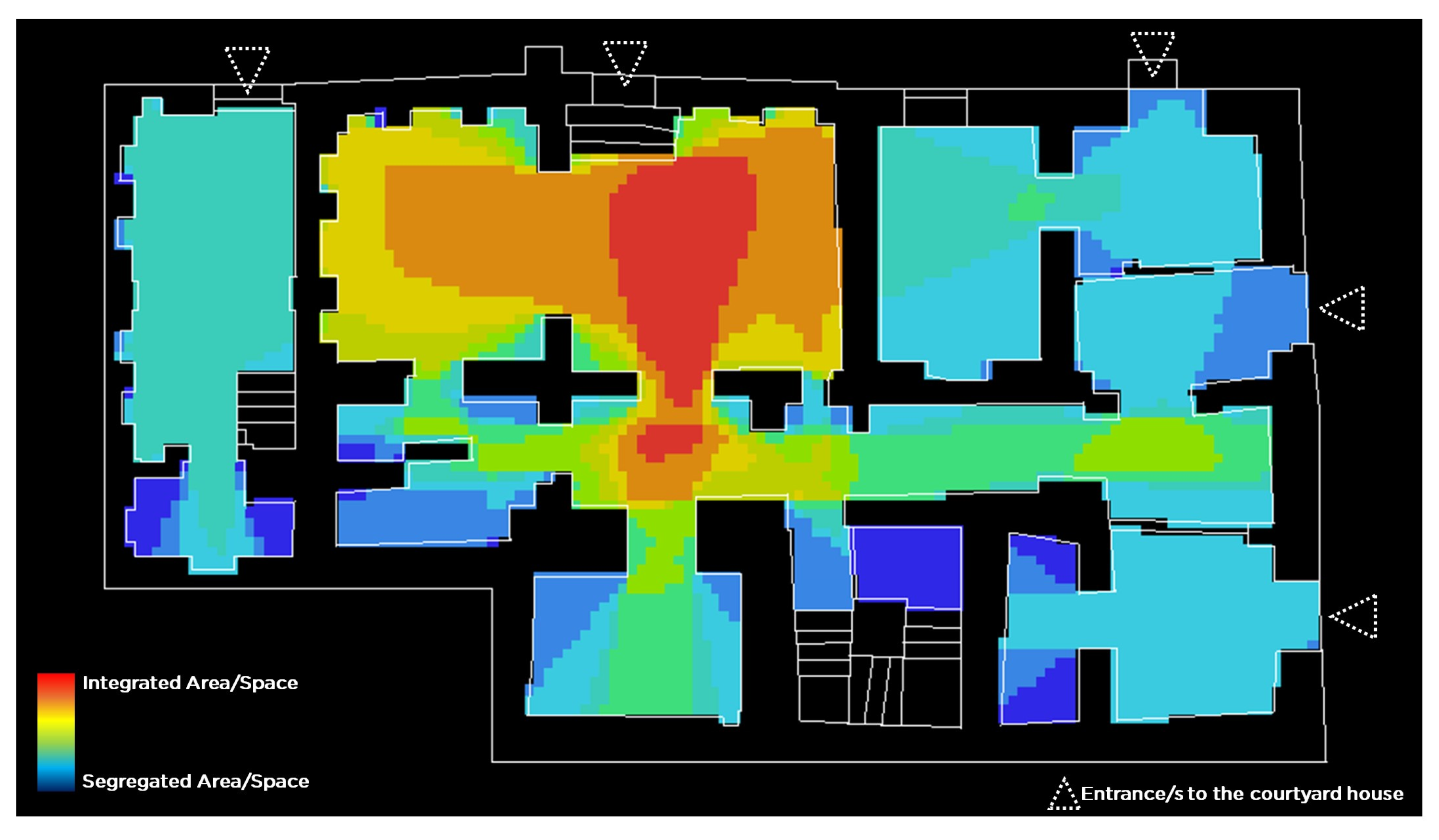

- 5.

Courtyard House Name: Al-Nawar House

Connectivity Performance Analysis: Although the courtyard is not central in its location as it directly appears after the main entrance, it remains highly connected to the rest of the spaces within the ground level, especially to the liwan. The rest of the entrances lead into spaces with lower connectivity patterns because of the isolated nature of such spaces for storage and commercial activities. The long and linear corridor is intermediate in connectivity, leading to the various zones of the household (

Figure 19).

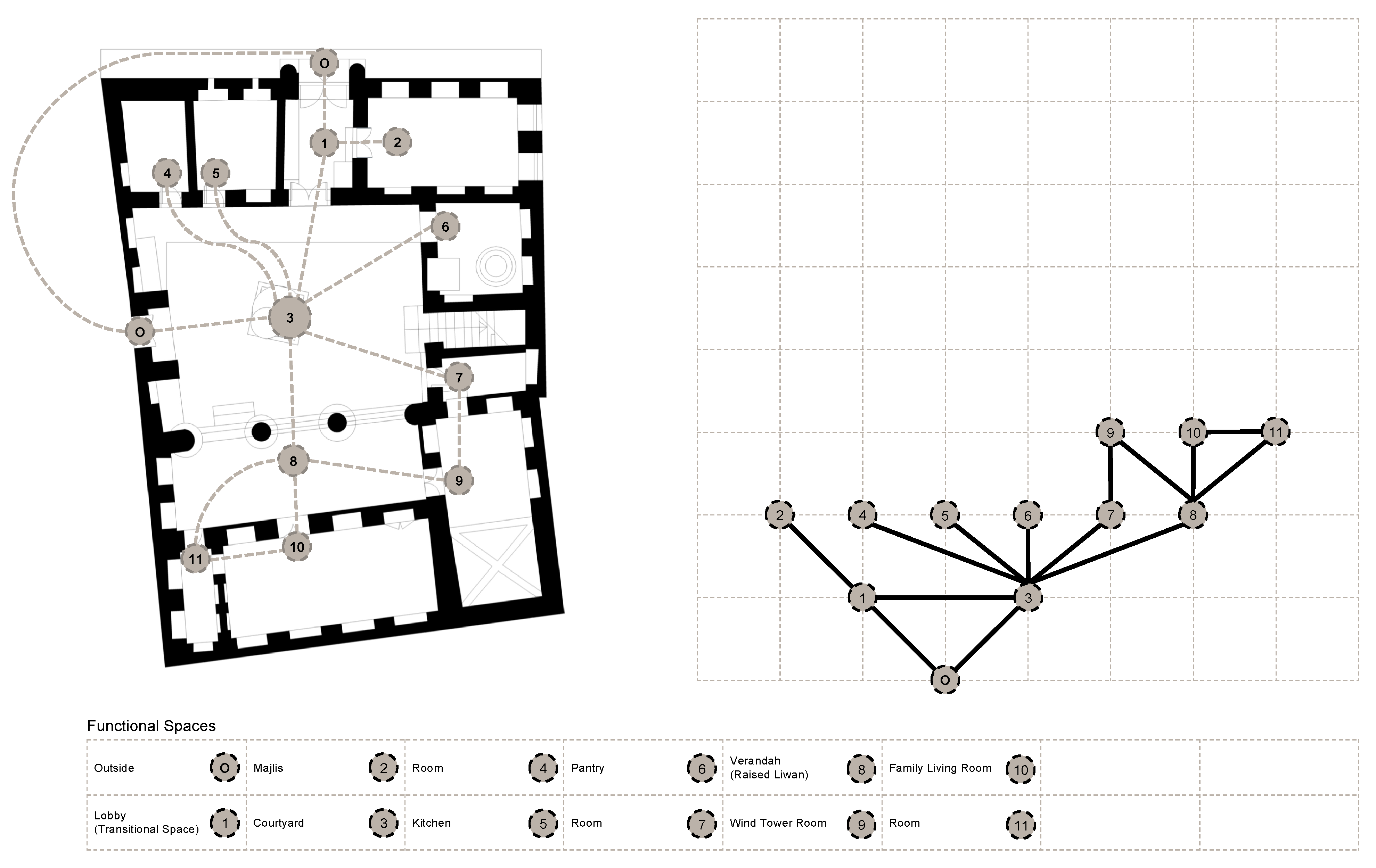

- 6.

Courtyard House Name: Abdul Qadr Rashidi House

Connectivity Performance Analysis: The spacious courtyard shows patterns of high visibility where it reaches its maximum level in some spots, as shown in the VGA. In general, most of the rooms that enclose the courtyard, as well as the majlis room, are low-to-intermediate in visibility, with shades of light blue rather than deep blue because of the rooms’ proportions and their direct visual accessibility to the courtyard. The main entrance is low in connectivity, while the side entrance opens directly into the courtyard (

Figure 20).

As a summary of the data analysis, the connectivity performance and the visibility analysis of the courtyard houses correspond to the built forms in that they generally tend to be high in courtyards and low in areas that surround courtyards. Around these highly visible courtyards, patterns of visibility signify intermediate connectivity that appear in the shades of orange and yellow in the VGA layouts. The remaining spaces and rooms on the perimeter of the houses are low in connectivity with VGA colors that range from light blue to dark blue.

The following table summarizes the entire collection of courtyard house plans, each with its respective VGA layout (

Table 1). The courtyards in these plans illustrate high visibility that aligns with their function and form. Some courtyards appear to be central in that they are entirely surrounded by rooms and spaces on the four sides, while other courtyards shift to one side of the household, forming a U-shaped built mass with refined visibility. Elements that refine the visibility in the courtyards include columns, arcades, central vegetation, or wells. These plans also have a special appearance of corridors, which appear as narrow connectors between the main entrances and the courtyards or as internal corridors across the different sections of the household.

The next section of this paper concludes and discusses spatial configuration and the most noticeable remarks on the visibility performance of the courtyards and their surrounding spaces. These remarks cover the criteria for analysis, including spatial form, socio-cultural factors, and the system of activities.

5. Discussion

The spatial configuration of courtyard houses relates to socio-cultural factors such as privacy, gender segregation, and hospitality. Hence, examining their spatiality allows for an understanding of the courtyard house’s formation as a social unit of space. This approach is useful in architectural sociology and urban morphology, where sociology and architecture interrelate through the understanding of collective identities that shape the built form and contribute to the conservation of social characteristics in buildings. The ultimate purpose of this research study is to prove the existence of common spatial patterns among courtyards in the vernacular houses of the Gulf.

In all six cases, courtyards are the most connected and visible spaces. These courtyards are mostly quadrilateral in form and physical configuration. In most of the houses, the main approach from the entrance to the courtyard passes through a passageway or an intermediate space. An exception is found in Al-Nawar House (#5), where one of its northern main entrances opens immediately into the compact quadrangular courtyard, which is further connected to the main household through an internal corridor and a staircase at intermediate-to-low visibility patterns. It is a special case because some spaces within the ground floor of Al-Nawar House have been used for commercial or storage purposes that require functional privacy because of the nature of the activities in them; therefore, these spaces must be isolated.

On the other hand, the remaining courtyard houses present a general trend of approaching from the main entrance door into the courtyard of the dwelling through a passageway or an intermediate space that is linear and narrow in form. These spaces take on green to yellow shades in the VGA, signifying their intermediate connectivity pattern. For instance, Rashidi House (#6) has an enclosed space or lobby that links the main entrance to the majlis room and to the courtyard, leading to the creation of a “ring” between the outside, the lobby, and the courtyard space, as shown in the justified permeability graph (

Figure 21). According to the theory of space syntax, such rings reveal social dynamics in permitting a “degree of the tuning of the host-guest relations in the house” [

56]. Subsequently, the branch that connects the nodes O-1-2 in the graph is a hospitality branch, whereas the spaces that connect to the courtyard marked as node 3 are household spaces. Another important note is the existence of the raised liwan, or the veranda (marked as node number 8), which mediates and connects the central node of the courtyard (node 3) to the private rooms ahead of it.

In view of gendered spaces, private family rooms and services such as kitchens are segregated spaces with low visibility patterns, attributable to either their formative configuration as small rooms or other architectural features such as the existence of entries or intermediate spaces between the private rooms and the courtyard. Another attribute that relates to gendered spaces is the existence of side entrances for the use of the family, as seen in the Rashidi House (#6) with its side entrance opening immediately into the courtyard and in Al-Nawar House (#5) with its multiple entrances.

Spaces for hospitality present specific visibility patterns and include majlis rooms. Depending on their configuration, hospitality spaces could have separate access. This is true in the case of Rashidi House (#6), where the majlis room has its own access point beside the main entrance. The majlis room has windows that open to the outside, allowing for good daylight, ventilation, and visibility. Similarly, Nadir House (#3) has a private guest reception room to the right of the main entrance.

Meanwhile, in the other cases, the houses have their majlis rooms within the household. The majlis room in the Nasrallah House (#4) is located in close proximity to the main door of the household, leading to very low visibility patterns in relation to the remaining rooms and spaces of the house. Similarly, in the case of the first house of Bahrain (#1), for example, the majlis room occupies a far-reaching corner of the courtyard house and connects to the main courtyard through a private entry and two small windows. The majlis room faces an arcaded liwan on the opposite side, which is in front of a living room. In this way, the majlis room and the living room remain secluded while maintaining their functional uses and system of activity, as well as retaining direct access to the courtyard. The J-graph of the house clarifies these spatial remarks (

Figure 22).

5.1. Patterns of Privacy

In the vernacular courtyard house of the Gulf, it is possible to relate the pattern of privacy to a number of connectivity scenarios covering gradual/graduated connectivity, balanced connectivity, and intermediate connectivity.

5.1.1. Gradual or Graduated Connectivity

The first scenario is gradual connectivity, where connectivity gradually increases from the private rooms to the central courtyard (

Figure 23). This scenario of connectivity is attributed to the socio-cultural patterns of privacy and the nuclear arrangement of the vernacular courtyard house. The spatial allocation of the courtyard in an open space surrounded by protected and private rooms supports its social purpose as a gathering spot. In addition to the courtyard, a scenario of gradual connectivity exists in the main entrance. The main entrance of the vernacular house is segregated near the door frame and gradually connects to the courtyard through intermediate forms such as narrow corridors or hallways. This scenario guarantees family inhabitants or visitors a high level of privacy from unwanted visual disturbances as they approach the household.

5.1.2. Balanced Connectivity

The second scenario is balanced connectivity. The rooms that surround the courtyard in a typical traditional courtyard house are narrow, small, compact, and private, while the courtyard is large, spacious, open-air, and public (

Figure 24). The connectivity is organic, leading to a house form in equilibrium. The small rooms provide equal opportunities for family members and women to own privatized spaces within the limited plot area. In addition, rooms and spaces in the courtyard house are multi-functional and flexible to changes in their assigned functions. Not only rooms, but the courtyard is also flexible in accommodating social activities.

5.1.3. Intermediate Connectivity

The third scenario is intermediate connectivity. The vernacular courtyard house has various transitional architectural forms of porches, vestibules, corridors, arcades, and liwan spaces (lawaween, plural of the singular liwan) as intermediate spaces between the courtyard and the various rooms and services in the household (

Figure 25). These forms are permanent structures rather than temporary fixtures or furniture. The intermediate forms allow smooth, gradual accessibility between the spaces. In terms of family activities, the intermediate spaces house various domestic and social activities such as daily gatherings and networking with neighbors, friends, and relatives, bearing in mind their climatically refined microclimate and their connectivity to the rooms and the courtyard alike.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

The paper examines the spatiality of vernacular courtyard houses in the Arabian Gulf region based on visibility analysis and with respect to the prevailing socio-cultural patterns of privacy, gender segregation, and hospitality, in addition to the inhabitants’ system of activities. This is a significant topic of analysis as it addresses the socio-cultural realities of Gulf societies and people’s practiced culture in the vernacular context. The analysis highlights the social sustainability of residential architecture in the Gulf and provides insights that can contribute to sustainable urbanism and promote social equity as a major pillar of sustainable urban design [

62].

This paper provides a collection of courtyard houses from the Arabian Gulf region to see if any consistencies could be uncovered in the spatial analysis and room arrangement, or in the way in which uses are assigned to different parts of the domestic interior. It provides visual analysis (VGA) of six courtyard houses from each Arabian Gulf country that were built in the period between the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries (1850–1950). The approach is to show that similar configurational arrangements among the courtyard houses in the Gulf still reflect distinctive lifestyles, forms of domestic space organization, and community life. Thus, the hypothesis is true in that it validates the existence of common spatial patterns in the courtyards based on space visibility and connectivity analysis, attributing it to socio-cultural factors and the inhabitants’ activity system.

In the vernacular courtyard house, therefore, socio-cultural patterns lead to gradual, balanced, and intermediate connectivity patterns. These findings illustrate the spatiality of the courtyard as a central, connected, and visible space within the vernacular household in comparison to the private and segregated rooms and services that surround the courtyard. In between, there are intermediate spaces, such as liwan spaces, porches, and vaults, which illustrate intermediate visibility patterns.

The findings are consistent with the evidence, as VGA reveals common spatial patterns (e.g., privacy-related view restrictions) among Gulf houses, supporting the hypothesis of social and cultural embeddedness or inscription. In this way, this paper uncovers the spatiality of the courtyard house in the Gulf and contributes to the fields of housing, socio-cultural studies, and architectural sociology.

The vernacular context is the main setting in this paper, yet our current contemporary built environment evokes various trends in residential architecture and in housing spatiality that require further interdisciplinary investigation. Contemporary trends create challenges in housing, such as the unresponsive formative design of the villa schemes to the socio-cultural needs, urban sprawl, and the absence of the neighborhood’s compactness and community values [

7,

63,

64]. It is a necessary recommendation for architects and urban designers to rethink the vernacular courtyard house in compact neighborhoods as a viable model in a harmonious system, which is sensitive to physical as well as non-physical imperatives.

7. Contribution to Knowledge

This research study contributes to the fields of housing and socio-cultural studies in the Gulf and Middle East regions. The application of the vernacular spatial design model to traditional Gulf architecture is novel, combining spatial analysis with social and cultural theory. Previous studies have focused on the climatic or aesthetic aspects of courtyard houses, while this work links spatial designs with social and cultural practices, filling this gap. Therefore, this study contributes to the integration of empirical spatial analysis with qualitative social and cultural frameworks, offering methodological advances compared with purely descriptive or historical studies.

This study fills knowledge gaps in architecture and sociology in a selected regional context. Precisely, the study has four main contributions:

It inspires the revival of architectural identity in a regional context while considering the nuances of place and the social setting. In fact, courtyard domestic spatial arrangements in the Gulf reflect the unique lifestyles of the inhabitants and further affect household organization and social life. Commonalities in the courtyard house type unite the regional architectural background, while differences give an architectural character.

This study helps resolve current challenges in housing spatiality by providing a reference to the vernacular as a foundational source of knowledge and as an inspiration for design.

This study provides a structured methodology using modeling and visibility analysis to assess houses in a socio-cultural setting. So, the outcomes of the methodology and the outcomes of the modeling could be useful in further research on the spatiality of regional housing.

This study foresees innovative development of courtyard designs in contemporary and futuristic housing prototypes, bearing in mind the spatial characteristics of the courtyard and its visibility beyond formative and physical attributes.

Researchers, architects, urban designers, and people interested in heritage and architecture can find in this study a suitable reference for providing a linkage between architecture and society with a historical background. Meanwhile, the visibility analysis proves that there is much more to explore in the region’s architectural heritage.

Limitations, Practical Implications, and Recommendations

Most of the courtyard houses in this study were documented in primary or secondary references, such as books, papers, or theses of regional scholars. As an implication for advancement, researchers should survey further sources of archival material and technical reports to enrich the content of vernacular domestic architecture and its forms.

This study has limitations in terms of the representativeness of the selected units of analysis. It relates to how representative these dwellings were of the set of such houses as a whole. Some vernacular houses not investigated here lack a clear courtyard style, which would have hindered the present analysis as it relates to connectivity and spatiality. This is another reason for limiting the number of housing units for review, precisely six vernacular examples.

Moreover, the limited number of housing units might have affected the reliability of the findings in this paper. The methodology could be improved by increasing the sample and expanding the scope of this study to include more than six houses (e.g., more than one house per Gulf country) to enhance generalizability. However, there is a scarcity of archival material and architectural references that document vernacular houses in the Gulf, since the field of historical building preservation and conservation is not highly practiced.

Certain criteria for analysis control the selection of the courtyard houses, including their approximate date of construction and approximate area. Some of the houses were not set to scale in their original reference. This led the authors to redraw the layout plans using known scales of doors or steps. Therefore, measurement errors might have occurred and affected the accuracy of the findings. Another noticeable limitation is the absence of space designation or labeled functional uses in some of the courtyard houses, leading to a limitation in the spatial analysis.

As a recommendation, since floor areas ranging from 200 to 600 square meters entail significant differences in the number of rooms and spatial circulation patterns in the courtyard houses, it is recommended to further narrow the range—for example, by limiting it to approximately 160 to 240 square meters, within a 20% margin of variation centered on 200 square meters. Meanwhile, the authors signify a noticeable lack of architectural reference of domestic forms across the Gulf; thus, they recommend enriching the existing body of knowledge through surveying, conservation, and documentation at both institutional and personal levels. The built heritage of the region is valuable, and future research approaches demand more intensity in architectural publication to foster regional interconnectivity.

The authors of this study urge fellow researchers in architecture to initiate similar methodologies that link to a robust theoretical framework, specifically to space syntax theory. A possible area of research would relate to the integration of space syntax with cultural or architectural meaning. The socio-cultural implications of spatial visibility, such as gender separation, privacy gradients, and climate responsiveness, prove to be researchable topics in space syntax in the domestic setting, precisely in unveiling the spatiality of vernacular houses across various epochs and regions of the world.