Abstract

This study aims to photograph, design, and digitally document the surviving residential buildings on the island of Halki (Heybeliada), within the Princes’ Islands. This documentation focuses on the architectural, urban, and historical aspects of Halki, highlighting the significant material evidence of the Greek social and economic presence. It also examines the urban cultural heritage as depicted in Turkish literature of that period to understand how Turkish writers perceived and presented Halki, referencing the Princes’ Islands only for background context. The methodology includes the collection of material from residents through bibliographic and field research conducted on Halki. Based on these findings, a mobile augmented reality (AR) application was developed using the TaleBlazer platform, designed specifically for use on Halki. The application provides a virtual tour with multimedia-supported thematic layers of architectural and historical information. Its usability and learnability were evaluated using a questionnaire completed by students. The results showed high usability, user satisfaction, and perceived value of learning, with the majority of results close to a median score of 4 out of 5. The students identified the occurrence of immersive experience, ease of use, and the emotional stimulation created by the integration of spatial storytelling and multimedia. This paper also shows how the convergence of cultural content (history, architecture, and literature) can enhance interpretations and experiences with mobile AR technologies.

1. Introduction

The Princes’ Islands, located near Constantinople, represent a unique geographical and cultural area in the world with a rich and long history of Greek presence. Among them, the islands of Antigoni (Burgazadası), Halki (Heybeliada), and Pringipos (Büyükada) are particularly notable for their historical and architectural significance. While these islands share a common cultural heritage, this study is limited to the island of Halki. Despite the islands’ significant historical, architectural, and cultural value, the residential stock and intangible heritage of the Greek community of Halki have so far been documented mainly in printed form [1,2,3,4], or through static digital media, such as websites which provide information and promote the area as a tourist destination. However, this heritage is still largely inaccessible and unfamiliar to the public. Consequently, a literature review of the geographical and historical evolution of the Princes’ Islands provided the conceptual framework for selecting Halki as the focus of this culturally significant case study.

In recent years, modern technologies have transformed the visibility and understanding of cultural heritage into an interactive experience by incorporating Augmented Reality (AR). There are studies [5] that have shown that AR applications provide immersive experiences and educational benefits. However, there are no AR applications specifically related to the Greek community of Halki, nor to a methodology that combines architectural and historical analysis with literary interpretation, using accessible technology for non-experts.

This paper attempts to fill this research gap through the implementation of an AR application that highlights the architecture and cultural heritage of the Greek community on the island of Halki, from the late 19th and early 20th century till nowadays. This study offers a coherent and easy-to-use application developed within the framework of the project. It combines architectural and historical analysis, literary references found in Turkish literary works, and digital interpretation, using the TaleBlazer platform. In short, this research work aims to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: How can AR technology be used to document and promote the Greek residential heritage οn the island of Halki (Heybeliada)?

RQ2: How can historical, architectural, and literary content be integrated into a mobile AR experience?

RQ3: How do users (students or visitors) evaluate such an application based on usability, learning experience, and cultural engagement?

This research contributes to the growing field of digital heritage in various ways by addressing these questions. It introduces an interdisciplinary and non-code-based approach to the development of AR applications. It also addresses a gap in the literature on mobile AR applications in post-Ottoman Greek local contexts. Furthermore, it provides a useful framework for educational practices that support the interpretation and communication of cultural heritage. To our knowledge, this is the first study to integrate historical and architectural analysis of Greek heritage, focused only on the island of Halki, with Turkish literary sources through a location-based AR experience.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on AR applications for cultural heritage. Section 3 describes the research methodology. Section 4 and Section 5 present literary, historical, and geographical background on the Princes’ Islands, serving as contextual framing. Section 6 analyses the historical and ekistic development of Halki, while Section 7 discusses architectural typologies as they are expressed on Halki. Section 8 and Section 9 present the design and the evaluation results of the AR application, respectively. Section 10 discusses key findings and future work plans, and Section 11 concludes this study.

2. Related Work on Location-Based Augmented Reality Applications for Cultural Heritage

Most location-based AR applications for cultural heritage adopt a user-centered methodology, typically beginning with requirements analysis, content curation, and platform selection. More specifically, in the work of Kleftodimos A. et al. [6], they discuss location-based applications used in various sectors, such as tourism, entertainment, marketing, and education. They emphasize that such applications can serve more than one purpose, giving, as an example, a location-aware AR game that could be used in the tourism sector to entertain and educate visitors to a specific destination, while, at the same time, achieving the goals of promoting the tourist destination. Accordingly, they designed two applications, “Once upon a time in Dispilio” and “Crime in the Lake Settlement,” keeping the idea of serving both by highlighting the area as a tourist destination and educating the applications’ users.

Another study focusing on the development of AR applications for this purpose is the one conducted by Koutromanos G., Styliaras G. [7], who developed the application “The buildings speak about our city”, which combines both location-based and marker-based AR. This game is designed to engage primary school students in discovering historic buildings that were formerly tobacco warehouses in their city (Agrinio, in western Greece), valued for their historical, architectural, and cultural significance. It also invites them to discover their relationship with the economic and cultural development of the city.

In conclusion, augmented reality is widely used to promote cultural heritage, so a design of a walking route would be a creative and easy way for application designers to highlight the cultural heritage that spreads over a large area, such as a prehistoric settlement (the applications of Kleftodimos A. et al.) [6] or tobacco warehouses that are located in the center of a city (the application of Koutromanos G., Styliaras G.) [7]. According to Kleftodimos A. et al., the results of their evaluation were positive, as the applications scored high in aspects such as perceived ease of use, satisfaction, and enjoyment. Both samples (university and school students) liked the storytelling application “Crime at the Lake Settlement” more, but, at the same time, they thought that more knowledge was gained through the informative application “Once upon a time in Dispilio” [6]. In the case of Koutromanos G., Styliaras G.’s application, their first evaluation results about the use of their application are encouraging, and they plan to conduct a summative evaluation [7]. Furthermore, the design of a walking route in a specific area of a city to highlight important historical events, along with the promotion of significant buildings, stands out, as was performed in the case of Cushing A.L. et al. [8] and the design of the application “Walk 1916”. In this case, the evaluation results show that “contextualizing access to digital surrogates within the App and its features allowed participants to perceive an enhanced understanding of Easter Rising events, perceive of the potential for life enhancement, and perceive of the ability to retain greater control over access and use of content.” [8]

In contrast to previous applications, our work presents the first AR application, namely “Exploring Halki’s cultural heritage”, which is specifically focused on the Greek cultural heritage of the island of Halki (Heybeliada), one of the Princes’ Islands. In the Princes’ Islands, there is a vibrant Greek community, despite the fact that they belong to another country, Turkey. Although the Princes’ Islands and the Propontis, in general, are a famous tourist destination and have a highly important historical and architectural background, it is not promoted or interpreted in a structured and accessible way. This application bridges that gap by combining historical narratives with the distinctive architectural elements of the buildings, offering visitors a deeper engagement. In addition, this application enhances the experience through the use of audio narration. Based on its wide acceptance, we understand that the public is not satisfied only by the image and new technologies; they need the audio elements to deepen their knowledge. Through storytelling, users are given the opportunity to travel back in time and imagine life as it once was on the island.

Regarding platforms and designing tools, based on the review by Chatsiopoulou A., Michailidis P. [5], it was found that the majority of AR applications were developed with low-level platforms and tools (such as Unity, Vuforia, etc.) that required advanced programming knowledge. Therefore, we could further explore the development of an AR application by using platforms that do not require coding. This is very important, so that creators or educators, who do not have a strong computing background, can design and develop AR applications for cultural heritage in a fast way, and these applications could be easily utilized in the educational process. Therefore, our work presents a novel, location-based AR application that is both content-rich and creator-friendly, aimed at promoting cultural heritage.

3. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the design and development process of the application, which was specifically developed to showcase the Greek cultural heritage of the island of Halki (Heybeliada), as well as the experimental setup used to assess its educational value in conveying cultural heritage. The methodology involved the collection of material related to the built environment, social life, and historical context of Halki. Brief preliminary visits were made to the other Princes’ Islands for contextual awareness and comparative framing. However, only data and visual material from Halki were selected and used in the application. This material was collected through bibliographic research and on-site visits conducted by two members of the team (Maria Panakaki and Vasilis Dimitriadis) between the 5th and 12th of October 2024. During the on-site research, photographs, drawings, and short interviews with members of the Greek Orthodox community were collected, all of which contributed significantly to this study. This research included the integration of selected excerpts from Turkish literary works that reference life on the Princes’ Islands, used solely to support the interpretation of Halki’s cultural setting. Afterwards, the application was designed by choosing the TaleBlazer platform developed by the MIT Scheller Teacher Education Program (STEP) lab. TaleBlazer is a user-friendly development tool that can be used even by designers without programming experience. The application includes a virtual tour that focuses on important buildings on the island of Halki. For each building, multimedia information about its history and architecture will be provided, and it will be presented through an interactive experience. The historical and architectural information is organized into two separate levels, allowing for personalized experiences that enhance understanding. This choice provides less information in each route and allows visitors to explore either architectural or historical narratives. Following up, the application was evaluated by a sample of 16 students during a course or presentation concerning the ekistics heritage in south-eastern Europe and the management of cultural heritage. The evaluation was conducted using a questionnaire, and it focused on four key factors such as ease of use, user experience, learning experience, and intent to use. The evaluation was voluntary and anonymous, and all students provided informed consent. The collected data from the research were analyzed using descriptive statistics with MS Excel.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the application was evaluated by a relatively small sample, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, this sample consisted of only sixteen students, and, in future research, it should be expanded to more diverse groups. Furthermore, there was a language limitation, since we designed the user interface of the application using only the Greek language. Therefore, the application is functional only for those who can read and understand Greek. Finally, the island of Halki was chosen because it is the only one where Greek merchants had built their residences along the old port. This specific road, Ayyildiz Cd., has buildings, or ruins, which belonged to Greek owners, and, for this reason, we used only photos of these specific buildings in the application. Furthermore, in 1844, the Theological School was founded there, making Halki the center of the educational renaissance of the 19th century in the area of the Princes’ Islands and Constantinople.

4. Princes’ Islands in Turkish Literature

The history and charm of the Princes’ Islands have always held an important place in Turkish literature. Throughout their historical journey up to this day, the islands are referred to by two names, Greek and Turkish, as follows: Pringipos (Büyükada), Halki (Heybeliada), Antigoni (Burgazadası), Proti (Kınalıada), Antirovythos (Sedefadası), Plati (Yassıada), Pita (Kaşıkadası), Oxya (Sivriada), and Neandros (Tavşanadası). The islands, both with their natural beauty and their character as places of isolation far from the crowds of the city, are a magnet for the people of Constantinople. During the Byzantine period, they were known for their exiles and prisons. However, from the mid-19th century onwards, they were transformed into places of rest, entertainment, and seclusion. With a significant Christian population and visitors from Europe, the islands offered a freer way of life compared to Constantinople, making them an attractive place to live.

The development of transportation allowed them to be used both as resorts and as destinations for day trips and short getaways. In addition to their natural beauty, they acquired additional charm thanks to the villas and famous hotels of the time. In particular, the villas impress with their aesthetic and architectural beauty and are described in literature with references to their architectural and topographical features. In this way, the islands are described as an exquisite cultural region, both in terms of the interior of the houses and the exterior spaces [1].

The Princes’ Islands were a place of residence or visit for Turkish writers, as they offered them tranquility, away from the hustle and bustle of Constantinople. Some writers settled permanently on the islands, while others spent certain periods of the year there. The islands, with their natural beauty, social life, and atmosphere, are suitable for love stories, have also been a source of inspiration for literary works. In the literary narratives of the last period of the Ottoman Empire, traces of this free way of life are clearly visible. People who move away from the social, traditional, and religious rules of life in Constantinople are drawn to the freedom of the social life of the islands and the idyllic image of nature; they adapt to it and change themselves.

One of these writers, Halid Ziya Uşaklıgil (1865–1945), in the descriptions of his story “Malım Menâlim”, seems to take into account space in relation to man, as the hero of his story, while traveling by ship, recalls his love for Shermet.

“That year, the whole island echoed with the famous waltz Tesoro mio by Becucci, and his love had been born and grown within its melodies. All the barrel organs of the island played this music. At the port, as the passengers disembarked, at Agios Nikolaos, the hill of Christ, Glossa, Giorgoulis, they encountered everywhere carriages waiting to greet them with the melody and the couples returning from their walks immersed in a sweet intoxication.”[9] (pp. 67–68).

Another writer, Sait Faik (1906–1954), who wrote 159 short stories and two novels, lived on these islands, specifically, in Antigoni. In his 65 works, he describes the Greek-Orthodox population of these islands [8]. In his writings, he mentions the fishermen who have identified with this island. Sait Faik, as he stated in his interviews, did not like the rich people with their supposedly aristocratic behavior. For him, the poor fishermen who earned their living from the sea were frugal people who, despite their poverty, knew how to enjoy life. The author believed that the people of the bourgeoisie did not know how to enjoy life and avoided spending time with them. In his works, one can find vivid and realistic images inspired by life, mainly in Antigone, as well as in Pringipos, Proti, Halki, Plati, and Oxya.

The short story titled “The ship of Stelianos Chrysopoulos” describes the life of poor fishermen of Antigone, who, despite difficult circumstances, continue to live happily and peacefully. The story focuses on the elderly fisherman Stelianos Chrysopoulos and his grandson Tryphon, who dreams of becoming a captain. Only these two are left alive from this poor fisherman’s family. Like all the fishermen on the island, old Stelianos places his hopes in the fish he will catch from the sea. If the catch is good, he wants to buy something for his grandson. However, most of the time, as he says, “the sea is empty.” Despite the difficulties, these fatalistic but tenacious fishermen do not even think of rebelling against their fate. They have learned to settle for little.

“...There were no fish this year. This year’s vacationers had not spent money as lavishly as in previous years. They had even bought the fish from another fisherman. He had not made a single cent in profit.

Tryfonas had fallen ill just before winter came. Medicines were expensive in the village. Going down to Constantinople was a whole big issue. Tryfonas, of course, did not go to school, but he studied on his own. Even books and notebooks cost a lot.

Stelianos intended to go fishing the next morning. He adjusted the feathers on his fishing line, mended the worn ones, the cut fishing lines and replaced the rusty hooks. He wished there would be plenty of fish tomorrow, so he could buy some oil, some sugar, a pair of trousers and a woolen vest for Tryphon, a cap for himself. He could tidy up the house a bit, bring some small gifts from Constantinople to Tryphon.”[10] (pp. 14–15).

On the islands, where there was a dense Greek population, social life was intense at the time when the relevant Turkish novels and short stories were written. The streets that were mentioned, neighborhoods, avenues, hills, hotels, and recreational areas represent real places and locations that were teeming with life. In our time, some are still preserved, while others have changed their names, and some have closed or no longer exist. Turkish literature has managed to save something of the atmosphere of that era.

5. Geographical and Historical Background of the Princes’ Islands

This section offers a concise historical and geographical overview of the Princes’ Islands solely to frame the subsequent case study of Halki. Any comparative references serve background purposes only.

Chalcedonian or Demounesian islands, Propontid islands, Erythronissa, Papadonisia, Pringiponissa, or simply “the Islands” are some of the names used to describe the island cluster near Constantinople. Lying on the northeastern edge of the Propontis, at the mouth of the Gulf of Nicomedia, they are located about 15 km from Constantinople. It is a cluster of nine islands consisting of four large ones, Proti, Antigoni, Halki, and Pringipos, and five smaller ones, Antirovythos, the “mid-island” Pita, Neandros, Oxya, and Plati.

Historically, the islands have been an object of reference since antiquity. Aristotle uses the names Demonisoi and Chalcedonian Islands, which are directly related to the ore-rich area. The settlement remains and movable finds that have been discovered from time to time are additional and indisputable evidence of the residence and activity that were developed by the ancient Greeks on the islands.

This trend continued both in late antiquity and afterwards; it is attested by a wealth of references in a variety of sources. From these sources, various names emerged, referring either to the entire island group or to individual islands. As time passed, the use of the area changed from a mining area to a vacation area, a place of worship, or exile, as evidenced by the relevant sources.

Naturally, the fate of the islands was closely tied to that of Constantinople. As a result, they witnessed repeated raids and disasters. After the Fall of Constantinople and until the normalization of the new reality, the situation was volatile [2] (pp. 33–52). However, gradually, and after administrative measures, the situation was normalized and a new chapter in the history of the islands began, during which the presence and activity of the Greek Orthodox populations was a catalyst, a presence that was to suffer crushing blows after the Asia Minor Catastrophe and the events of 1955 and onwards. Today, only a small number of Greeks live in the Pringiponissa (Princes’ Islands). They remain the last guardians of a long-standing Greek presence and activity in the area.

The choice of islands described below is based on the extent of their surviving settlement stock, with the island of Proti excluded due to its limited number of remaining houses. The historical period examined spans from the late 19th century to the present to assess the preservation status of these buildings as contextual background.

5.1. Antigoni

Despite their shared history and similarities, each island has its own distinct anthropogeography and development. Antigoni1 is presented first here as comparative background for the Halki case study. The rocky island, with an area of about 1500 m2, has as a characteristic landmark a 170 m high plateau, where the monastery of Theokorifotou was located during the Byzantine period. On the coastal front, the southern side, which is not easily accessed, becomes less rugged towards the west, forming bays and beaches. However, thanks to the northeastern side of the island, in ancient times Antigoni was called Panormos [11]2 [4] (pp. 211–215).

The original residential core of the island was located around the magnificent Church of Agios Ioannis Prodromos, which was built in 841 A.D. The other church on the island is the church of the monastery of St. George Karipi, which was probably built in the 17th century. Finally, in terms of educational institutions, the island had a primary school until 1974. Today, due to a lack of pupils, it has stopped operating and is used as an office space for the community [12].

5.2. Pringipos

Pringipos is discussed solely for background comparison. Moving on to Pringipos3, the largest of the Princes’ islands, it has been noted that the settlement was gathered in the northeastern part. The development of the settlement was centered on the church of Agios Dimitrios and a seaside square, whose coastal staircase served sea transport in the early 19th century [2] (pp. 77–84, 93).

The island has two mountain peaks, the highest of which reaches 202 m. and hosts the Monastery of Agios Georgios of Koudounas, while the second one reaches 156 m. and the Monastery of Christ is built on it. Between the two areas, the altitude is lower, creating a neck of land, and the location is called Diaskelo. The roads connecting Chora to the two monasteries are considered to be the first to be built and the most important, as the settlement of the last two centuries was organized around them [13].

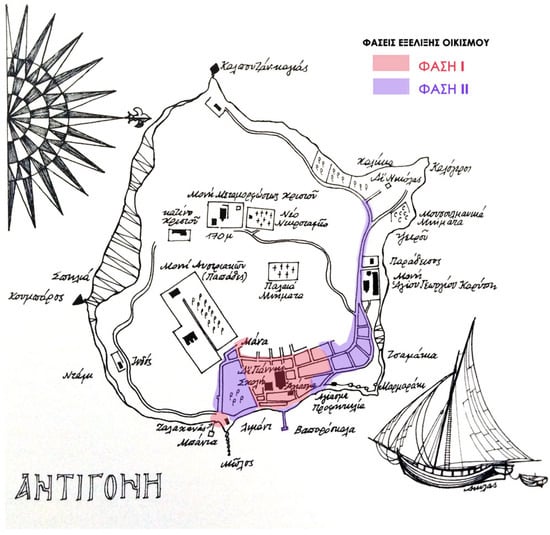

A comparative visual representation of the development phases of Antigoni and Pringipos is provided in Appendix A and Appendix B, offering additional spatial context for understanding their historical urban growth.

6. Geographical, Historical, and Ekistic Development of Halki

This section provides an overview of Halki’s geographical and historical background, followed by an analysis of its ekistic development.

6.1. Geographical and Historical Background

Halki4, the second largest island of the cluster, is almost triangular in shape and is distinguished by three mountainous points, in the north, east, and west of the island. Of these, the highest, located in the west, is Koutroulomilos5, which rises to 136 m high. This mountain continues to the east and forms a twin peak, a little lower at 128 m. The second-highest mountain extends to the west and is named Christos, because of the skete of the Metamorphosis of Christ that was located there. Finally, to the north is the third mountain, the historic hill of the Holy Trinity, better known as the hill of the Theological School, and its height reaches 85 m.

Between Koutroulomilos and Agia Triada stretches the rich valley of Halki, where in the past there were cultivations with vineyards and vegetable gardens that reached the foot of the mountains. Today, however, this area is inhabited. The eastern end of the valley reaches the harbor, where the site of the settlement has been located since ancient times.

On the second neck formed between the Koutroulomilos and the hill of Christ, the historic monastery of Panagia Kamariotissa was built and dates back to before the Palaiologians’ era. To the south, a large olive grove extended to the “port of Panagia”, now known as ‘Tsamlimani’ or ‘Pefkolimenas’, where the ancient copper mines were located.

East of Pefkolimenas, the boundaries of the third great monastery of Halki began, Agios Georgios of Krimnos, which included the cemetery and reached the seaside pavilion of Skarlatos Karatzas, where the Naval Imperial School (Kislas) was established between 1800–1824 [3] (pp. 21–26, 51).

Historically, in Halki, as in the other inhabited islands, Greek Orthodox populations (Romioi) lived, many of whom came from the Peloponnese, as an aftermath of the Orloffics, along with Chians and Cycladic people, during the 18th century. During the 19th century, Halki, like the other islands, experienced remarkable growth on multiple levels. It is indicative that in 1821 the island had 800 inhabitants, and, by 1875, it had reached 3500. It was a station for important events of the Greek Revolution, as the Philikoi gathered there [14].

In 1844, the Theological School [15] (pp. 402–440) was founded on the hill of Agia Triada in order to meet the needs of the Ecumenical Patriarchate for theological and ecclesiastical training of the clergy, but it was also a reflection of the educational renaissance of the 19th century [16]. In the Theological School, they were taught the Greek language, theology, philosophy, rhetoric, political history, experimental physics, mathematics, geography, ecclesiastical music, and four foreign languages, Latin, Slavonic, French, and Turkish. There was also a Boys’ School, a Parish School, and a Kindergarten.

From 1835, the Hellenic Trade School, or the “Hellenic School of Education”, as it is also known, had been operating in the monastery of Panagia in Halki [17] (pp. 90–94). It had about 140 boarders, 11 teachers, and they taught the Greek language, holy scriptures, rhetoric, philosophy, elementary mathematics, physics, history, geography, and four languages: Turkish, French, Italian, and English. At the same time, the Imperial Naval School was flourishing and expanding westward, creating the Ottoman Quarter.

During the second half of the 19th century, a group of select and educated people gathered on the island. Many rich merchants and their families also came for holidays and built their own resorts.

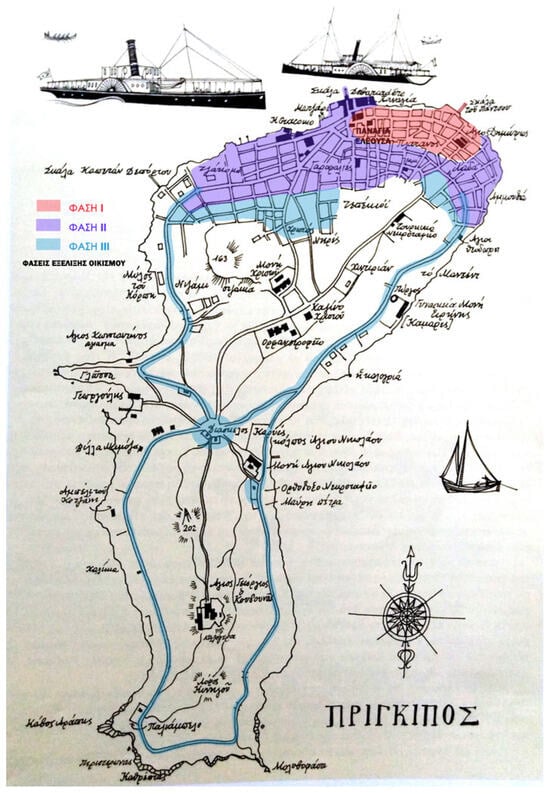

6.2. Phases of Ekistic Development in Halki

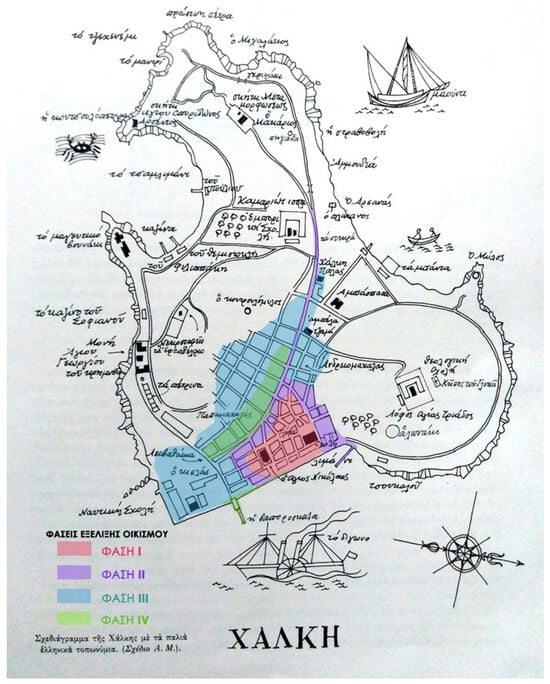

In the next subsections, the phases of development of Halki are analyzed. In Halki, there are four phases of development. Τhey are shown on the map (Figure 1) in different colors: pink is for the first phase, purple for the second, light blue for the third, and light green for the fourth phase of development.

Figure 1.

The phases of the settlement’s development of Halki. Source: Drawing by A. Millas, editing by M. Panakaki.

6.2.1. Phase 1: Old Chora—Around Agios Nikolaos

Since ancient times, the area of the port of Halki has always been inhabited. Halki was a coastal village facing east, and its main area was called “Chora” in the old days. This first settlement was built around the church of Agios Nikolaos and the Glyfa Wells [3] (p. 23).

6.2.2. Phase 2: Old Road Axis of Panagia and Extension of the Settlement—Galentzadika—Port—Loggia

By the middle of the 19th century, the settlement was extended, and a main traffic road was formed, which almost crosses the whole island in parallel to the coastline. It is the extension of the old road of Panagia, which is intersected by smaller streets of the areas of the church, Glyfa and Galentzadika [3] (pp. 23–24). These cobblestone and earthen alleys constituted the original settlement. The center was the port and the Loggia, the first road in front of the beach, where all commercial activities were gathered.

Galentzadika was an old fishing neighborhood of Chora, and it was built around the second big well of the island (the first one was in Glyfa), behind the wooden cells of Agios Nikolaos. There were low houses, wooden or made of stone and mud, in narrow and winding alleys. This settlement was completely destroyed by the second fire of 1902 [3] (p. 168).

The harbor was located to the east, on the side of Glyfa, in front of Molos, where the large boats docked, while the smaller ones docked to the west, in front of the Kamara Square.

6.2.3. Phase 3: Extension to the Cemetery-Papamachalas-Ampela

Shortly before the middle of the 19th century, the village of Halki had expanded considerably towards the cemetery, higher than Papamachalas and Ampela, having created new neighborhoods.

With the establishment of the Turkish Naval School, the area of Kisla was expanded to include a pavilion for the Sultan and a mosque with a bathhouse. Similarly, the Turkish professors and the families of Naval School officials, who had settled there, formed a Turkish quarter behind Kisla and towards the side of St. George’s Monastery. The road leading to their area, which was originally called “St. George’s Avenue”, was renamed the “Sailors’ Spring” road [3] (p. 60).

At the same time, many Cycladic families settled on the island, mainly Naxians and Andriots, but also Chians, who had escaped the massacres. The Andriots, who were mainly builders and stonemasons, renovated the Monastery of Agia Triada. They inhabited the foothill, and the district of Andriomahalas was created [18] (p. 232).

6.2.4. Phase 4: Changes and Evolution of Maritime Transport (Steamers)

In the middle of the 19th century, the first steamships appeared, and life in all the Prince Islands changed rapidly. Areas that were previously gardens and vineyards became plots of land for Greeks and Armenians, where they built resorts and villas.

The areas with impressive buildings were the “Livadakia”, where the aristocracy used to gather, with a large promenade in front of them, and its extension toward the “Platanakia” area. Furthermore, in the area of Papadomahalas were the scholars and professors who worked in the schools that operated in Halki [3] (pp. 71–72).

In Loggia, the first coastal promenade, shops, cafes, and casinos increased in number. The quay now had a new pier, where steamboats used to come and go all the time.

7. Architecture of Halki Within the Princes’ Islands Context

To better understand the architectural landscape of Halki, this section provides a brief comparative overview of architectural characteristics shared among the Princes’ Islands, with an emphasis on how these are reflected in Halki.

The buildings on the Prince Islands are mainly two-storey (with a ground floor and a first floor). Few are three-storey (with a ground floor and two floors), and rarely are ground-floor buildings.

Their construction is either mixed (brick or stone base or brick and stone and wooden storeys), or of one material. In particular, the base of the buildings is usually made of stone and brick and refers to the foundation, the basement, the semi-basement, and the ground floor. The upper floors are usually made of wood (with some stone buildings having only the top floor constructed of wood). On Halki, this typology is chiefly represented by the mansions at Livadakia (Figure 2). Buildings that use one material are either of stone, brick, or wood, but they always have stone foundations.

Figure 2.

Hephaestides’ resort at Halki in Livadakia. Source: Research program archive, October 2024.

The construction material also influences facade decoration, as it determines how elaborate the details can be. In wooden buildings, the facades are formed with horizontal boards and inlaid prefabricated decorations that imitate architectural elements of all styles.

Some of those wooden buildings imitate elaborate stone buildings, which can be found in Pera and Galata, and are called “kagiria” [18] (p. 241). The stone buildings were more austere, without, of course, lacking in plaster frames, bands, and other architectural details, wherever those could be incorporated (in cornices, opening frames, etc.). Brick buildings were even more austere as the material can produce simpler decorations, because of its specific dimensions.

In the initial old area of settlements, the sizes of buildings are smaller than those found in their later extensions (Appendix B, Figure A4). These buildings are usually built close together. The entrance of the building is either from the street or from the side, creating at the same time a passage to the courtyard at the back of the plot, when this exists. Towards the harbor, where the original fishing settlements were developed, the buildings are distinguished by the simplicity of their decoration or the complete absence of it.

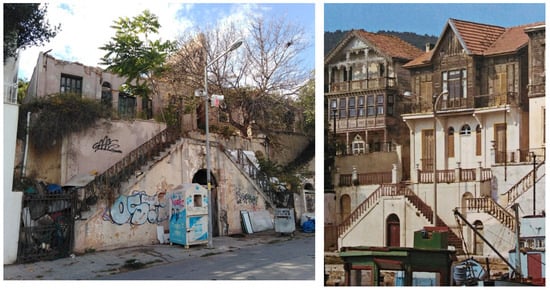

Villas and large mansions are found in the extensions of the settlements (Appendix B, Figure A3). These buildings usually have open spaces in front of the main door, creating monumental entrances. Sometimes, the approach from the public space is made by monumental staircases with double spirals and opposite arrangements. In other cases, there are usually stairs leading to the entrance, either at an upper level or at a lower level. These buildings are placed in the middle of their gardens and are characterized by their symmetry. Centrally on the façade, there is a “sahnisi” (closed balcony) or a balcony supported on consoles and crowned with a simple pediment, or a pediment including the attic at a higher level, or in other simpler manner, which certainly makes an impression.

The architectural style characterizing this period is eclecticism. It is therefore a fact that in a single facade we can distinguish more than one element of a different architectural style (classicism, art nouveau, Italianate, Gothic, etc.) combined in order to form quite impressive facades or simply to make a stylish structure, depending on the preferences and social background of the owner (Figure 3). Beyond the decorative choice, however, the cosmopolitan composition can be seen in the extensions of island settlements whose inhabitants came from distant places or had travelled there.

Figure 3.

The remnants of Voutiras’ mansion in Halki today (left), and the original building (right) as it was photographed by A. Millas in 1978. Source: Research program archive, October 2024, A. Millas’ archive in 1978.

In conclusion, in terms of settlement, through the recording of the historical and architectural course of the evolution of the islands, we can see not only the long presence of Greek elements in them, but also their beneficial contribution, often in spite of the times. By looking at these surviving residential ‘works of art’, one can reflect on the extent of the cultural heritage of Halki and the heavy responsibility of the few continuators of this tradition.

8. Designing Application “Exploring Halki’s Cultural Heritage”

This section presents the design and implementation of the augmented reality application developed specifically for the island of Halki. The application aims to promote Halki’s cultural and architectural heritage to visitors and learners, also enabling a “virtual” walk within a classroom setting.

Τhe island of Halki was selected for two main reasons. Firstly, the route we chose to highlight is in front of the island’s old port, something that is not found on other islands. The second reason is that Halki is a place of significant historical value, as the Theological School was founded there in 1844. It was not only the place where the clergy was trained, but it was also a reflection of the educational renaissance of the 19th century [16].

The application was designed by an interdisciplinary team, with each member assigned a specific role. Two members of our team, the architects, were in charge of the architectural and urban planning part of the application, while the historian was responsible for the historical context and another member, who is teaching Turkish language and literature, supported the literary side of the application, since he presented the Princes’ Islands of that era (early 20th century) through Turkish literature. Finally, two other members, who are in the field of digital application designs, were responsible for the implementation of the application. Throughout the whole procedure of the design, there were discussions between the members regarding the requirements of the application.

The aim of the “Exploring Halki’s cultural heritage” application is to offer an interactive tour to visitors, combining information and visualizations of architectural and historical elements.

The application includes a route of six stations, which are houses (or what is left of them) that belonged to Greek owners on the coastal front of Halki. These stations were selected by the group based on a field trip to the island of Halki, conducted by two members (Maria Panakaki and Vasilis Dimitriadis) from 5th to 12th October 2024. Since the information that was intended to be included was a lot and there were important things, both historical and architectural, that needed to be presented, it was suggested to create two players for the same stations: the archaeologist, who discovers historical information during the walk, and the architect, who focuses on architectural and urban planning elements.

The information is displayed in the form of text, 2D images which include both modern depictions of space and older photographs from literature research, as well as short recorded clips. The multimedia content, i.e., the appearance of texts, images, and audio clips, is triggered based on geolocation, depending on the user’s location. The application is available in Greek, with future planning of being available in English as well. It is an easy-to-use application, and, if someone follows the installation instructions for their mobile device, they can easily use it and perform its functions. When the application was designed, it was intended to be evaluated by higher education students, but it is basically available to anyone who wants to visit the site either in person or remotely, following the route without the use of geolocation. The user must download the “TaleBlazer” application to their mobile device and enter the code in the “gamecode” space (code: gchamwb) to download the game. The game selection opens, the user downloads it, and the application is ready to be used. The application is available to anyone who has the code to download it.

For the development of the application, the “TaleBlazer” [19] software platform was chosen, as it is one of the friendliest environments for the application creator. TaleBlazer is an open-source platform for developing geolocation-based AR games for both outdoor and indoor environments. Developed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), it features a block-based visual programming environment, allowing commands to be inserted without any previous programming knowledge. TaleBlazer is suitable for people without programming experience, as it allows the design of interactive applications in a simple and understandable way. The choice of TaleBlazer was based on study-specific criteria such as ease of use, geolocation integration, and free availability. In contrast, other available low-level platforms, such as Unity, Vuforia, or Apple’s ARKit, provide greater flexibility and realistic visualization capabilities, but require significant programming expertise and greater development resources [5]. Therefore, TaleBlazer was chosen because it best meets the educational and research needs of this study, while maintaining an easy-to-use and sustainable development environment.

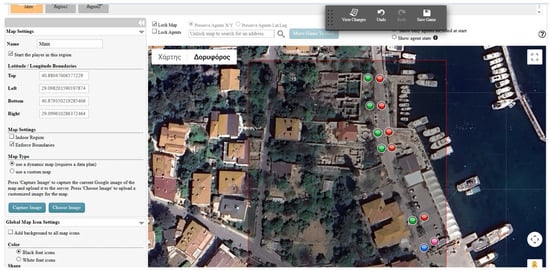

Starting the design of the application, we selected the coordinates of our location, thus setting the map on which the application would be developed (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Designing the map—printed screen from the TaleBlazer platform while working on the app. Source: Personal archive, Chatsiopoulou A.

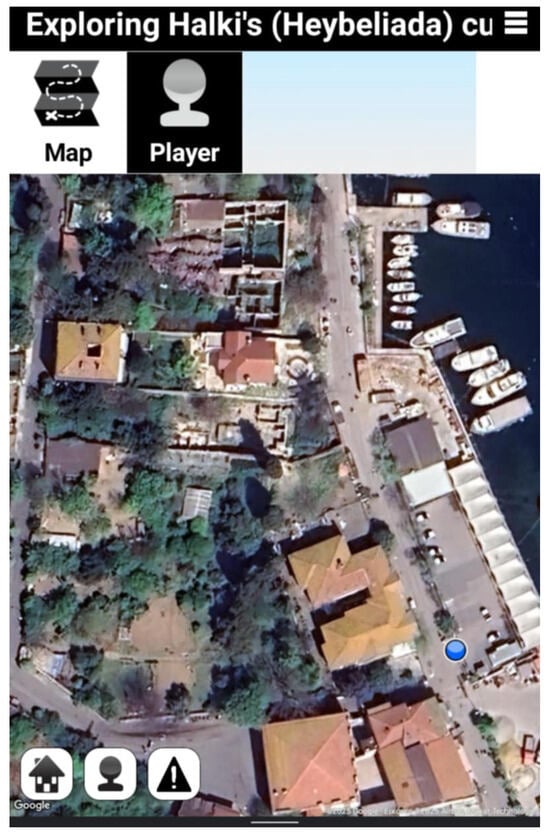

Then, we placed the main stations on the route we proposed. These stations are placed approximately in front of the residences (or what is left of them). In this way, the user would be able to stop in front of them, and the information would be activated, following the GPS activation. The stations in blue and pink colors are the ones that start the route for the “Historian” and the “Architect”, respectively. If the user chooses the “Historian”, he will stop at the stations in green color. If he chooses the “Architect”, he will stop at those in red color. The same map, during the use of the application, can be viewed as in Figure 5, and we can see that only the first stop is shown (for the “Historian”), as it is designed to appear that the stops gradually appear as we pass through the points we have set.

Figure 5.

The map in the application, following the route of the “Historian”—printed screen of a mobile device while using the app. Source: Personal archive, Chatsiopoulou A.

As it was mentioned before, the design of the application is easy on this platform, since we are given a block in which we enter the commands needed for its development. Initially, we selected the point on the map that would be connected to the stop, thus defining the first “Agent”. Moving to the next step, through the “Agents” tab, we formatted the first stop. We defined its exact location so that, when the user passes by this point, the stop will be activated via the geolocation system (GPS). We chose a photographic representation of the specific stop as an image of a part of the coastal front of Halki. In the description of the stop, we gave a brief introduction to the place where the application user is located: throughout the historical course of the Princes’ Islands, and to this day, the islands are referred to by two names, in both Greek and Turkish, as follows: Pringipos (Büyükada), Halki (Heybeliada), Antigoni (Burgazadası), Proti (Kınalıada), Antirovythos (Sedefadası), Plati (Yassıada), Pita (Kaşıkadası), Oxia (Sivriada), and Neandros (Tavşanadası).

On the whiteboard, as shown in Figure 6, we wrote the commands that determine the appearance of the stop on the map: when it appears, what will happen when it appears, and how the second stop will appear immediately after its completion.

Figure 6.

Designing the first “Agent”. Printed Screen from the Taleblazer platform while working on the app. Source: Personal archive, Chatsiopoulou A.

To include more information about the history and architecture of these buildings and the cultural heritage of the wider Princes’ Islands area, in some descriptions of the stops, we uploaded a short audio clip with our own recording, recounting the atmosphere of the area and mentioning special features of the buildings located on the route. The recording was made by using TTS maker [20], which is a free text-to-speech conversion tool.

In Figure 7 (screenshot on the right), the first stop is presented as it appears in the application. The user can proceed to the next stop by pressing the “OK” button if they are using the application remotely. The other stops on the proposed route have been created in the same way. Although it looks more like a virtual tour of the site, the fact that it is available for each user’s mobile device and can be handled by everyone at their own pace makes it an interesting way to approach a place with such an important cultural reserve.

Figure 7.

(On the left) The menu with two players: historian and architect. (On the right) The first stop in the application. Printed screens of a mobile device while using the app. Source: Personal archive, Chatsiopoulou A.

The amount of information about the buildings and the area is too extensive to be presented within a single icon, which could overwhelm the application user with too many different topics. So, two types of players were created in the “Player” tab, the “Historian” and the “Architect”, dividing the information into two types. The stops are the same for both routes; their only difference is that each route focuses more on historical or architectural topics. The user can select one player when the application starts, as shown in Figure 7 (screenshot on the left), but they can choose a different one next time to learn something different. In Figure 8, we can see the process of designing the player of “Historian” in the platform: when the application starts, it checks if the user has selected the role of the “Historian” and if so, it displays the first station as shown in Figure 5. In Figure 9, we can see how the player (“Historian”) appears in the application if the user wants to check what role they chose before.

Figure 8.

Designing the “Historian” player on the TaleBlazer platform. Source: Personal archive, Chatsiopoulou A.

Figure 9.

The “Historian” player in the application. Source: Personal archive, Chatsiopoulou A.

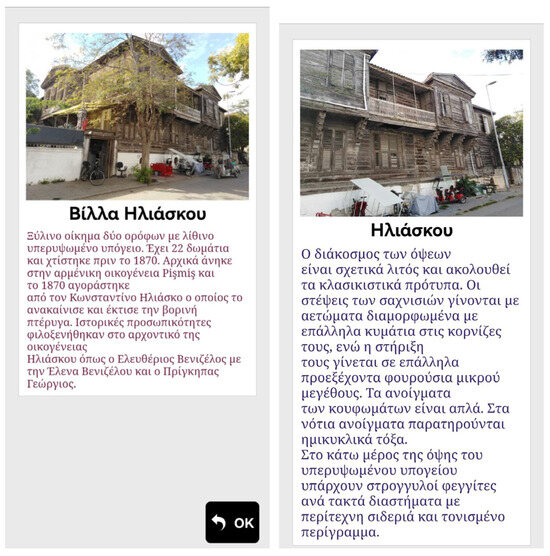

We can see such an example in Figure 10, where we can find the second station (Iliaskou mansion). The screenshot on the left is the station as it appears on the “Historian” route, including more information about its history. The screenshot on the right is the station on the “Architect” route, including more information about its architectural elements. The image is different, as we try to enhance its architectural and structural elements and its architectural style.

Figure 10.

The second station—Iliaskou Residence. On the left is the station as it appears to the Historian route, and on the right is as it appears to the Architect route. Screenshots of the application. Source: Personal archive, Chatsiopoulou A.

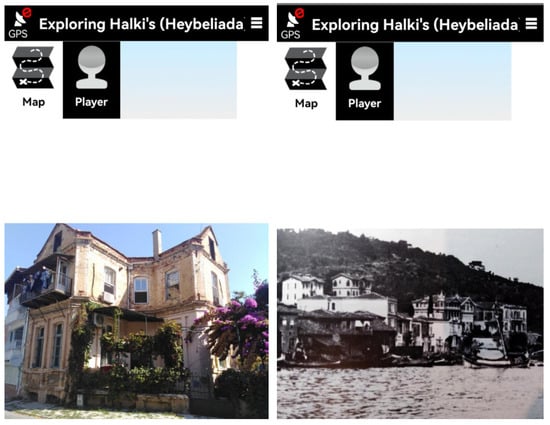

Following those steps, we moved on to the next stops for both players. Finally, we chose an image that shows how was the front of the old port in Halki for the end of the route of the Architect and a well-preserved villa in Pringipos for the Historian. When the user visits the last station, these images are revealed to him respectively for each route (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Images after the end of the route. On the left is the one for the historian route, and on the right for the architect route. Screenshots of the application. Source: Personal archive, Chatsiopoulou A.

For the audio part, as was mentioned before, we have chosen the TTS maker in order to make a small audio part for the first and the fourth stop in both routes. This platform allows us to insert the text we want and the music part as a background to convert it into a whole audio part (Figure 12). The music part we chose is called “Tesoro mio” from Becucci [21], a piece of music which was famous in the early 20th century, which was played a lot on the Princes’ Islands, information that we learnt from the writer Halid Ziya Uşaklıgil [9] (pp. 67–68). Both of the audio parts that are used enhance the narrative, and the users who evaluated the application approved this addition, and they suggested we use it in all of the stations.

Figure 12.

Screenshot of the open platform TTS Maker. Source: Personal archive, Chatsiopoulou A.

9. Evaluation

To evaluate the “Exploring Halki’s cultural heritage” application, a presentation was conducted as part of the courses “Cultural Heritage Management in Urban and Rural Areas (Balkans, Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean)” and “Spatial Development—Urban Policies in Southeastern Europe” at the University of Macedonia (spring semester 2024–2025). During the course, an introduction to the region and the application was first presented, followed by instructions for the application’s use, and the students were guided through a virtual tour of Halki. Then, an anonymous questionnaire was given, which was going to evaluate the application in terms of usability and user experience. The questions of the questionnaire are presented in Appendix C and are based on a 5-point Likert scale.

The evaluation sample consisted of students from the Department of Balkan, Slavic, and Oriental Studies (BSOS) of the University of Macedonia who were enrolled in these courses during the spring semester of 2024–2025. The research sample consisted of 16 participants. The sample selection followed a non-randomized convenience sampling method, as the participants provided direct access to this study and had the necessary technological infrastructure to download and use the application. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Macedonia. Participation was voluntary, all responses were anonymous, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

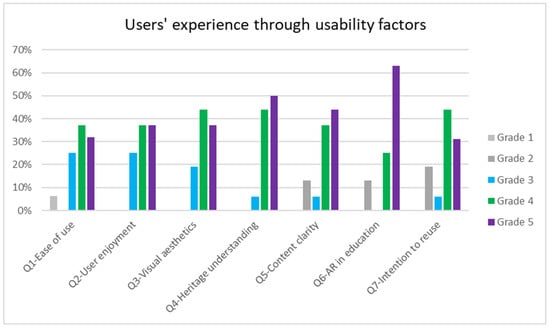

This section presents the results of the evaluation of the usability and user experience of the AR application, as derived from the questions of the questionnaire. The analysis focuses on four key factors: (a) usability and ease of use, (b) user experience, (c) learning, and (d) intent to use. According to the results of Table 1, the majority of students found the application relatively user-friendly and easy to use (median = 4). For questions 4–6, the median is close to 4.5, indicating that the reviews are very positive regarding learning new content related to cultural heritage, whether the material presented in the application was understandable, and whether the use of AR applications in educational courses would be helpful.

Table 1.

Average and median of usability factors.

The median of question 7 (median = 4) indicates that over half of the sample positively evaluates the application in terms of user experience and their intention to recommend it to friends and visitors.

Graphical representations and analysis of the data by question are shown in Figure 13. Figure 13 illustrates the users’ responses, based on the 5-point Likert scale, where total disagreement is given with 1 and high agreement with 5. To begin with, Question 1 assesses how easy the application was to use and concerns the factor of “Usability and ease of use”. We can see that 93.7% agree that the application was easy to use. Both questions 2 and 3 depict the factor of “User experience”. In question 2, which shows how enjoyable it was to use the app, everyone gave a high rating (3–5), and the same results were given for question 3 about the overall aesthetics of the app.

Figure 13.

Bar chart of response distribution for each question.

The next three questions (questions 4, 5, and 6) show results about the factor “Learning”. In question 4, which is about the contribution of the AR application “Exploring Halki’s (Heybeliada) cultural heritage” contributes to the understanding of the cultural heritage of the region of Asia Minor and Princes’ Islands, 93.7% gave a high score (4–5 grades), but the results of question 5, which is about how understandable the presented content is through the application, are slightly lower: 81.2% voted highly positively (4–5 grades) and 18.8% voted medium to lower grades, indicating that they did not fully understand the presented content. In question 6, which is about the extended use of AR applications in lessons to enhance the educational experience more interesting, 62.5% gave the highest score (5 grade), indicating that they are positive about using AR applications in order to learn in a more fun and interactive way. Finally, in question 7, which concerns the factor of “Intention to use”, most of the users will probably recommend this application for learning about cultural heritage to friends and visitors, since 13 out of 16 gave a positive rating (81.2%).

The last question was open-ended, where they could write their comments. Their comments show that most participants found it to be an engaging approach to the cultural heritage, which “opens new ways for the recording and highlighting of the ekistics and cultural heritage, for educational and tourist purposes”. Another student claimed that “It makes the experience very vivid so you don’t lose interest, the voice tour makes you feel very close to what you’re seeing”, while others give suggestions for improvement: “It would be really nice to have vocals at all stations”.

The fact that this application highlights and documents the cultural heritage of Asia Minor by combining different contexts of history, architecture, and literature is considered one of the main advantages we have detected. Furthermore, this application showed us that it can be used as a spatial storytelling tool, since at various points with the help of GPS, information and multimedia content are activated, giving a sense of “freedom” to the user, who does not have to do anything to activate the content. Finally, the enrichment of the stops with audio clips, which were not only plain information, but they had also parts of a song that was very famous at that time, gave a different dimension to the narrative, allowing the users to “listen” to whatever the local residents were also listening in the early 20th century for entertainment.

10. Discussion

This section discusses the findings of this study in relation to the three research questions. Regarding the first research question, the proposed application showed that AR can serve as an effective tool for spatial storytelling. The integration of historical and architectural content in a location-based experience showed that the application enables users to perceive cultural information in context, in a way that enhances understanding as well as emotional engagement.

Regarding the second question, the decision to include two role-based players in the mobile AR application proved effective in reducing cognitive overload and allows users to explore cultural content according to their preferences and interests. Although similar to applications developed by previous researchers [7], this project presents notable differences. The application follows a linear path, beginning and ending along a coastal route in Halki. Following this route, by choosing a different player (Architect or Historian) each time, the user can assimilate a lot of information (architectural and historical) about these buildings without becoming overwhelmed, as users can follow the route at their own pace. The player selection feature allows users to choose the type of information they wish to explore, and after the end of the route, they can start over by choosing the other option. This game element was previously presented in the Koutromanos G., Styliaras G. research [7], but it is unclear whether they implemented this feature in their application, whereas we successfully incorporated it into ours, through the platform TaleBlazer. Also, the enrichment of the stops with audio clips, which are either informative or give the perspective of the Turkish writers of the time, helps the user to absorb the information in an easy and relaxing way.

As for the third research question, the results of Table 1 show that the majority of students claimed that the application is relatively user-friendly and easy to use, since the factors “Usability and Use” and “User Experience” have a median = 4. The median of factor “Learning” ranges between 4–5, indicating that this application is extremely useful to someone who wants to enrich their knowledge with new content related to cultural heritage. Last but not least, the median of question 7, which represents the factor of “Intent to use”, is also 4, showing that the majority of the students who used the application will possibly recommend it to friends and visitors. Therefore, we can see that positive results were obtained, which is a common element with previous research and applications [6,7,8].

However, we should keep in mind that our work has some limitations. The first limitation concerns the evaluation of the proposed AR application, which was based on a small sample size (only 16 students who successfully tested and evaluated the application), so the results cannot be generalized. For this reason, the evaluation should be extended to a larger and more diverse group of participants, including mixed target groups (like tourist groups). The results presented in this study reflect an initial stage of the application’s evaluation, which remains ongoing. The second limitation relates to language, since the names of the locations are in Greek and Turkish, but we only managed to insert them in the audio parts of the application in Greek. Moreover, we have focused only on one island, Halki, thus limiting the locations that someone can visit with the application. In order to improve our application and solve some of these problems, we intend to provide multilingual support, giving at least the option of English language to the user of the application. If the user menu of the application and texts were written in English, the language barrier that currently exists would be eliminated. Since the English language is spoken and used by most people around the world, the application could have a broader audience and be more widely used. Another future suggestion could be the enhancement of the application with more audio parts at the stops, since it is a very useful tool that was mentioned, through the evaluation process, to be used more extensively. We are planning to design similar applications for the other islands, in order to highlight the cultural heritage there as well. Finally, there is strong potential for gamification in order to make the application more interactive and entertaining for users. Giving the user the opportunity to interact, play, and participate in the learning process will make them have more fun while using the application. An idea of interaction would be a “treasure hunt”. During this hunt, users would have to follow clues provided by the application and try to gather all the evidence that shows the location of a hidden cultural item. This item could be a traditional song that was very popular on this island or a historical document concerning the island’s cultural heritage. This type of gamification mechanism has the potential to enhance both user engagement and learning outcomes.

11. Conclusions

This work examined the documentation and interpretation of the Greek cultural heritage of the island of Halki from historical, architectural, and literary perspectives, highlighting how these elements contextualize its built environment. Based on this framework, it also presented the design, development, and evaluation of a location-based AR application, “Exploring Halki’s cultural heritage”, designed to offer a guided and interactive experience focused on the island of Halki. The application was designed only for Halki, since it holds the most significant cultural importance in the Princes’ Islands region, particularly due to the presence of the Theological School, which was founded there in 1844.

This research demonstrated that multidimensional cultural content (history, architecture, and literature) can be effectively embedded in a mobile AR application using a dual-player content approach (historian and architect). This structure allows the application to offer narrative diversity and thematic depth, enabling users to explore both the spatial and symbolic layers of the island’s heritage.

The results of the evaluation were positive as participants found the application to be useful, easy to use, and narratively engaging. This means that AR application provides a comprehensive and immersive experience for users navigating both physical and digital layers of heritage. The successful integration of spatial data, historical content, and audio storytelling demonstrates that such tools offer not only rich user experiences for cultural heritage exploration but also potential for both tourism and educational use.

The proposed AR application contributes to the field of digital cultural heritage by proposing a methodology that allows non-experts to engage in AR design using low-cost software platforms. More specifically, the application combines spatial data, architecture features, literary content, and personal memory into a unified interpretive experience with relative ease. The positive results from the evaluation suggest that such tools are not only technically feasible but also provide immersive experiences in the context of cultural heritage.

Nevertheless, the current study faces some limitations, such as audience scope, gamification, and multilingual support. Future research efforts should focus on expanding the application’s audience (tourists, school groups), increasing interactivity with gamification techniques, and integrating it with a variety of heritage strategies, such as educational programs and tourist tours. Furthermore, we intend to design similar applications for the other two islands, Antigoni and Pringipos, using the same methodology. It would be interesting to assess user responses and engagement with these new applications, as was the case with the “Exploring Halki’s cultural heritage” application.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G.G., P.D.M., N.L., A.C., M.P. and V.D.; methodology, E.G.G., P.D.M., N.L., A.C., M.P. and V.D.; software, A.C.; validation, A.C., E.G.G. and P.D.M.; formal analysis, A.C.; investigation, M.P., V.D., A.C. and N.L.; resources, M.P. and V.D.; data curation, M.P. and V.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C., M.P., V.D. and N.L.; writing—review and editing, P.D.M. and A.C.; visualization, A.C., M.P. and V.D.; supervision, P.D.M.; project administration, E.G.G.; funding acquisition, E.G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is part of a project that has received funding from the University of Macedonia Research Fund under the Basic Research 2023 funding program in specific research areas. The research program is called “Cultural and Ekistic Heritage of the Greek Communities of Propontida (Asia Minor)”, Rescom code: 82331.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Contextual Background: Development Phases of Antigoni and Pringipos

Starting with Pringipos, three distinct development phases can be identified. The first phase is marked with the pink color on the map (Figure A1). Until the middle of the 19th century, the boundaries of the settlement started from the east, near the church of Agios Dimitrios, and extended westwards to the area of the church Panagia Eleousa. Near Agios Dimitrios were the ruins of Byzantine bastions and the large Platanos, where the square of the same name is located. These areas were also known as Pyrgos or Kato Pigadi. The square of the large Platanos (Kato Platanos) was connected by a central artery that led to the other square of the small Platanos (Pano Platanos) near the church of Panagia Eleousa [2] (p. 78).

Even further west and inland, at Garofalies, were the cultivated areas with vegetable gardens and vineyards.

Towards the beach was the “Loggia”, the coastal road where shops, workshops, cafes, and fish taverns were located. Further to the east was the old harbor, at Panjo’s site, where there was also the inn with the same name. There, the fishing boats and the long boats that served the traffic with the opposite areas were moored [2] (p. 77).

The second phase of Pringipos’ development is marked in purple (Figure A1). In 1867, Baudouy landfilled the steep beach in front of the Livadi (the site of Panagia Eleousa) the St. John, and the tombs, and created a new quay, the so-called Débarcadère, or the “Steamship Pier” [2] (p. 30) of Pringipos. Traffic increased on the island due to the steamships and the settlement expanded into the formerly cultivated areas.

Figure A1.

The phases of the settlement’s development of Pringipos. Source: Drawing by A. Millas, editing by M. Panakaki.

The third phase is shown in light blue on the map (Figure A1). At the end of the 19th century, the two main roads were extended in line with the expansion of the settlement. The St. Nicholas Road and Rue Giacomo were joined at Diaskelo, creating a roundabout called “Small Circle”.

In Karyes, next to the Monastery of St. Nicholas, there was a Byzantine settlement. The road passing through the area continued parallel to the coastline and around Mount St. George, creating the “Great Circle” [2] (p. 31).

On the island of Antigoni, according to the map in Figure A2, two phases in the settlement development can be distinguished (pink color for the first phase and purple color for the second phase).

Before the middle of the 19th century, as was the case in the rest of the Prince Islands, the small wooden houses of the original fishermen’s settlement were gathered around the Church of St John the Baptist. These buildings climbed steadily up the eastern slope of the mountain. Some were two-story stone buildings, and rarely three-story. Commercial activities, taverns, and cafés were gathered on the beach. [4] (p. 214).

The main road was the market street and a vertical road that passed by the huge plane tree and led to a spring called “Mana tou Nerou” (“Mother of Water”, which was a Byzantine water reservoir with ancient wells from which drinking water was drawn.

The second phase is characterized by the arrival of the steamships (Figure A2). After the mid-19th century, when steamships began to operate, the right side of the pier was built, and wealthy merchants of Pera chose to live there, building impressive resorts and private wooden baths, until the Chami (pine tree) site [4] (p. 272).

Figure A2.

The phases of the settlement’s development of Antigoni. Source: Drawing by A. Millas, editing by M. Panakaki.

Appendix B

Contextual Photos: Buildings in Antigoni and Pringipos

Appendix B contains photos of buildings in Antigoni and Pringipos which show the similarity of architecture in the Princes’ Islands.

Figure A3.

The former hotel “KALYPSO” in Pringipos. Source: Research program archive, October 2024.

Figure A4.

The “cell of the Priest” next to the Church of St. John the Baptist in Antigone. Source: Research program archive, October 2024.

Appendix C

Questionnaire

- Question 1: How easy was it to use the “Exploring Halki’s (Heybeliada) cultural heritage” app? [1,2,3,4,5];

- Question 2: How enjoyable was using the “Exploring Halki’s (Heybeliada) cultural heritage” app? [1,2,3,4,5];

- Question 3: How would you rate the overall aesthetics of the application? [1,2,3,4,5];

- Question 4: How much do you think the AR application “Exploring Halki’s (Heybeliada) cultural heritage” contributes to the understanding of the cultural heritage of the region? [1,2,3,4,5];

- Question 5: How understandable was the content presented through the “Exploring Halki’s (Heybeliada) cultural heritage” application? [1,2,3,4,5];

- Question 6: Do you think that using AR applications in lessons would make the educational process more interesting? [1,2,3,4,5];

- Question 7: Would you recommend the “Exploring Halki’s (Heybeliada) cultural heritage” app for learning about cultural heritage to friends or visitors? [1,2,3,4,5].

Notes

| 1 | Its Turkish name is Burgaz ada, probably because of the high ruins of the monastery of Theokorifotos, which referred to a tower. |

| 2 | An enclosed bay, one that is entirely suitable for mooring or disembarkation |

| 3 | Its Turkish name is Büyük ada, meaning the big island. |

| 4 | Its Turkish name is Heybeli ada, which in Greek is rendered as “with a horse saddle”, because of the resemblance of the hills and the valley that passes through the middle of them with a saddle. This image is visible from the sea. |

| 5 | The name is due to the ruins of an old mill of Panagia Kamariotissa. |

References

- Millas, I. Images of Greeks and Turks; Alexandria Publication: Athens, Greece, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Millas, A. The Pringipos; Mnimosini Publication: Athens, Greece, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Millas, A. The Halki of the Pringiponnisa (Princes’ Islands); Mnimosini Publication: Athens, Greece, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Millas, A. Proti, Antigone. The Pringiponnisa (Princes’ Islands); Mnimosini Publication: Athens, Greece, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chatsiopoulou, A.; Michailidis, P. Cultural Heritage Applications Based on Augmented Reality: A Literature Review. In Extended Reality: International Conference, XR Salento 2023, Lecce, Italy, September 6–9, 2023, Proceedings, Part II; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleftodimos, A.; Moustaka, M.; Evagelou, A. Location-Based Augmented Reality for Cultural Heritage Education: Creating Educational, Gamified Location- Based AR Applications for the Prehistoric Lake Settlement of Dispilio. Digital 2023, 3, 18–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutromanos, G.; Styliaras, G. “The buildings speak about our city”: A location based augmented reality game. In Proceedings of the 2015 6th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems and Applications (IISA), Corfu, Greece, 6–8 July 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushing, A.L.; Cowan, B.R. Walk1916: Exploring non-research user access to and use of digital surrogates via a mobile walking tour app. J. Doc. 2017, 73, 917–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uşaklıgil, H.Z. Kadın Pençesi; Özgür Yayınları: İstanbul, Turkey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Abasıyanık, S.F. Semaver; Remzi Yayınevi: İstanbul, Turkey, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Entry Panormos. Available online: https://www.greek-language.gr/digitalResources/ancient_greek/tools/liddel-scott/search.html?start=420&lq=%CE%A0 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Parizianos Antonis. Interview by Vasilis Dimitriadis and Maria Panakaki. Personal interview. Antigoni, Turkey, October 2024.

- Gümüş Korhan. Interview by Vasilis Dimitriadis and Maria Panakaki. Personal interview. Halki, Turkey, October 2024.

- Prokou Ekaterini. Interview by Vasilis Dimitriadis and Maria Panakaki. Personal interview. Halki, Turkey, October 2024.

- Tsilenis, E.S. The building of the theological school in Halki. In A Tribute to Professor Vassilios N. Anagnostopoulos; Society for the Study of the Anatolian World: Athens, Greece, 2007; pp. 402–440. [Google Scholar]

- The Holy Theological School of Halki on the Website of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Available online: https://ec-patr.org/oikoymeniko-patriarxeio/idrymata-organismoi/iera-sxoli-chalkis/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Alexandris, A. The Byzantine past of Constantinople: A Journey to the Famous Prigiponnisa and the Greek Orthodox Monasteries. ESTIAzo Mag. 2017, 5, 90–94. [Google Scholar]

- Poridis, A. Pringiponissa, the social and architectural configuration of space in its historical dimension. In Proceedings of the Culture and Space in the Balkans (17th–20th Century), Thessaloniki, Greece, 21–22 November 2014; Tsotsos, G.G., Gavra, E.G., Gkioufi, K.P., Eds.; University of Macedonia Press: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2015; pp. 229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Taleblazer. Available online: https://taleblazer.org (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- TTS Maker. Available online: https://ttsmaker.com/el (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Becucci, E. Tesoro Mio (Waltz). Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=31cx1mEovzI (accessed on 21 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).