1. Introduction

In the summer of 2023, in the area between Cagli and Pergola in the Marche region of central Italy, the authors conceived, organized, and supervised the “Design Thinking & Digital Heritage Workshop”. The workshop aimed to introduce an innovative practice, integrating VR, digitization, and narratives for cultural heritage experiences, with the goal of generating ideas and tools for design and decision-making processes, while considering their potential to engage communities in shaping future visions for their territories.

This article presents the experimentation with interdisciplinary, multi-scalar, and international knowledge-based design approaches employed during the workshop, analysing their strengths and weaknesses and discussing their practical and strategic implications for inner areas and the historical centres of Appennino Basso Pesarese–Anconetano (ABPA). The interdisciplinary learning activity was part of the RAILtoLAND (RtL) project, a co-funded Erasmus+ initiative under Key Action 2 “Cooperation for Innovation”. The RtL project serves as a collective ideation platform for developing innovative tools to communicate European Cultural Landscapes via train, with the goal of exploring the social and educational value of the railway landscape as shared heritage and a catalyst for strengthening European identity and local cultures. A key factor in the perception of cultural heritage is the influence of transportation on how landscapes are seen, observed, assimilated, and described, which in turn shapes regeneration and conservation strategies.

The workshop contributed to subsequent activities and reflections on the territory and its needs, leading to technology transfer activities between academic research and local institutions, which is in line with the third mission of Italian universities. Despite the short timeframe, thanks to the use of several different skills and tools (digital and non-digital), the workshop proved effective through demonstrating its integration into ongoing processes and subsequent cross-fertilization with stakeholders.

In this article we describe the context of intervention, the background materials, the state-of-the-art methods the literature and the methodology of this study in the chapter “Methods and materials”. We then summarize and discuss the workshop and research’s outputs in the “Results”, where not only the workshop’s outputs are described, but also the RtL project’s activities are compared with similar ones to identify the workshop’s original and innovative features. They are analysed in the “Discussion” chapter.

2. Materials and Methods

This chapter outlines the materials and methods adopted in this research, providing a structured framework for understanding the investigation process. The first subsections are dedicated to describing the intervention context of the RtL project workshop, offering a comprehensive overview of the site, objectives, and scope of the study. Furthermore, a review of the state-of-the-art methods in the disciplinary fields of architectural and urban design related to local development processes, as well as in the field of digitization technologies applied to heritage, is presented. This review summarizes previous research conducted on the key topics addressed in this study.

In the

Section 2.3, the scientific research method is examined in detail. This section clarifies the approach adopted for data analysis and interpretation, justifying the selection of specific methodologies and techniques. The objective is to establish a transparent and replicable framework for this study, ensuring the validity, reliability, and robustness of the results.

2.1. The Context of Intervention

The workshop activities took place in and focused on Cagli and Pergola, two rural-mountain municipalities of ABPA, which is an area defined by the National Strategy of Inner Areas (SNAI) [

1]. In 2014, when created, this was an innovative national policy of local development to fight the marginalization and demographic decline characterizing rural and remote areas in Italy. The latter are identified through specific indicators: distance from essential services (education, healthcare, and mobility) and rich in natural and cultural resources. Despite the abundance of historical, cultural, and architectural heritage distributed throughout the studied territory, the isolation of these villages—caused by the absence of a railway network, limited public transportation, and challenging mountain roads—results in a constellation of autonomous centralities. As noted in the ASviS report [

2], such areas are “placed on the margins of development and lack the endogenous, market, and political forces necessary to autonomously escape what can be described as an underdevelopment trap”. Although the area is traversed by two historically significant routes—the Via Flaminia to the north and the Strada Clementina to the south—reaching the essential services in the nearest municipal centres, Urbino and Fabriano, remains difficult. This is due to the reliance on provincial roads and the absence of an active railway line, which, though partially present, is no longer in regular use. The short Fabriano–Pergola railway line was operational until 2013 and was only reopened in September 2021 as part of the

Ferrovia Subappenninica Italica route, covering the Ancona–Fabriano–Pergola stretch. However, it operates only at specific times of the year and exclusively for tourism purposes [

3]. Despite the SNAI’s efforts to strengthen inter-municipal connections through joint projects, the workshop municipalities, Pergola and Cagli, continue to face significant challenges, including weak infrastructure and cultural isolation. In these areas, growing neglected and degraded, hinder active citizenship and contribute to social inequality and discomfort [

4]. However, they also contain numerous “potential spaces” [

5]—abandoned areas often regarded as urban residues [

6,

7,

8]—which hold considerable regenerative potential due to their historical and emotional ties to local identity. The central Apennines can and must be viewed as a large urban system [

8], as it has the potential to become an example of coexistence with the ecosystem and a vector of quality of life and landscape. For this reason, it is essential that environmental protection and the transition towards a sustainable, circular socio-economic model become the focal point of every development project for the Apennines [

9].

2.2. State-of-the-Art Methods

2.2.1. Preliminary Research Activities Framing and Addressing the RtL Project Workshop

The ABPA, the municipality of Cagli, and the concept of “potential spaces” have been the focus of the PhD research project RESETtling APPennines. Supported by analyses conducted within the Research Project of National Interest (PRIN) Branding4Resilience (B4R), this research has carried out extensive studies on the focus area and engaged in long-term fieldwork, involving dialogues with local administrations and communities. The analyses conducted, the material collected, and the relationships established with local administrations provided a crucial foundation for the Design Thinking & Digital Heritage Workshop. RESETtling APPennines, in fact, had already carried out numerous surveys, photographic campaigns, and laser scanning and acquisition of panoramic photos. The PhD thesis, however, not only contributed to providing material on which to carry out readings and visions (aerial plans and mapping, photos, historical research, and a literature review), but also made it possible to establish the main topics of workshops, identifying places and addressing strategies on the basis of the needs and weaknesses of the area. The choice to work on the former convent of San Francesco and on the Pergola railway station, in fact, turns out to be in line with the identification of the “potential spaces” and with the philosophy adopted by the thesis, i.e., to reactivate selected places, according to an adaptive reuse, with zero land consumption and with a focus on slow mobility and public spaces. Despite the materials already available, it was necessary to rework them for a proper preparation of the workshop, which moved in parallel along three paths: a dialogue and exchange with the Marche Region and the municipal administrations of Pergola and Cagli for content-related and logistic aspects, a methodological and management organization relating to the structure and the outputs of the activities to be carried out, and finally, a practical preparation of the materials to be worked on.

The dialogue with regional and municipal authorities proved productive, facilitating a better understanding of the territory’s needs and enabling the development of coherent and context-sensitive results. Additionally, fostering new relationships between local administrations and universities underscored the essential role of research in generating territorial enhancement strategies and stimulating new dynamics within and between municipalities [

10].

The preparation of the methodological structure of the workshop, described in the next chapter, took place in parallel with the previous step: the tutors had to understand how to ensure that the theoretical and the practical lessons, the surveys, the lectures, and the production of the final outputs, as well as the knowledge of the area of intervention, could enrich one another, complement each other, and allow the students to benefit the most. For this reason, it was decided to structure the program in such a way as to alternate the scheduled activities.

Moreover, workshop preparation also entailed assembling and refining the materials required for the working sessions. Preliminary site visits and surveys were conducted at both the Pergola railway station and the San Francesco complex. These surveys incorporated the use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS), and the GNSS system, enabling fast and precise data acquisition. This approach facilitated efficient data processing during the workshop, allowing students to grasp the methodology and workflow without being overly burdened by the lengthy and sometimes mechanical tasks associated with data collection and management.

2.2.2. The Use of ICT in Co-Design

Rather than focusing solely on research into innovative ICT tools, the novelty of the RtL project’s workshop lies in the interaction between ICTs and architectural and urban design throughout its various stages. ICTs have transformed the field of participatory design, enhancing citizen and stakeholder engagement in decision-making processes [

11]. This served as a foundational premise for our research, which leveraged cutting-edge technologies—specifically 3D point clouds, 360° environments, and immersive technologies—that are already available and effectively utilized in interactive activities involving territories and communities.

However, the use of these technologies is often confined to facilitating public participation, while their potential to foster interdisciplinary dialogue among researchers or to serve as a design tool remains largely underexplored. In recent years, various initiatives in different contexts have demonstrated the added value of 3D digital environments and interactive platforms in urban and social design processes. These tools have proven effective in visualizing future scenarios, understanding the implications of design choices, and promoting more informed interactions among planners, local administrations, and communities [

12,

13]. Nonetheless, the state-of-the-art analysis conducted for this research reveals that ICTs are rarely employed to enhance interdisciplinarity and design thinking among multidisciplinary researchers. Typically, both communities involved in participatory processes and researchers within their respective projects receive ICT-generated outputs as finalized products—processed over extended periods—and use them independently for their own objectives. In contrast, the short timeframe of the RtL project’s workshop “forced” participants (including both students and tutors) to actively engage in all phases of the process, from surveying and data processing to urban and architectural design. Within the RtL project’s framework, ICT-generated outputs were not merely final products but served as tools for dialogue, discussion, and design throughout both the ideation and experimentation phases.

2.3. Methodology

The methodology adopted in this research is structured in two main parts. The first section outlines the methodological framework adopted in the RtL project’s workshop, detailing its various stages and the specific approaches implemented throughout its development. The second part expands the scope of the investigation beyond the workshop itself, incorporating a subsequent research phase dedicated to collecting examples and best practices from similar experiences. Through a comparative analysis of these case studies, the research identifies both innovative aspects and potential weaknesses, offering a broader perspective on methodological effectiveness. The primary objective of this second phase is to ensure the scalability and replicability of the research, ultimately providing scholars in related fields with a practical toolkit for design thinking and digital heritage approaches.

2.3.1. The RtL Project Design Thinking Workshop’s Methodology

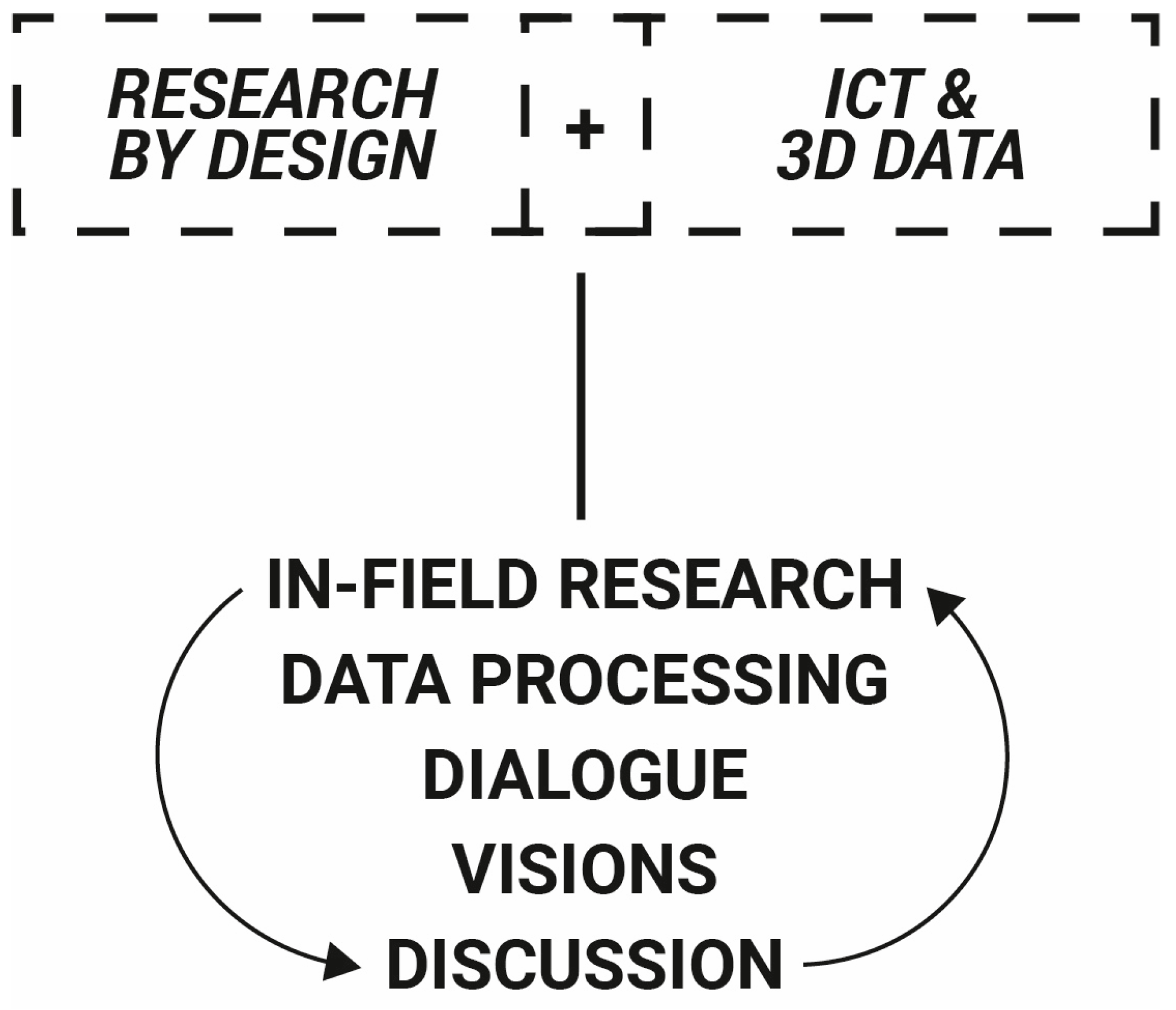

The workshop structure takes as a reference and as a starting point the design thinking framework developed and experimented by IDEO [

14]. The first phase begins with in-field research and it entails a discovery phase where initial data are collected and insights are gathered directly from the context under study. The second step involves data processing and interpretation where raw data are organized, analysed and transformed into meaningful insights to inform conclusions. The third step, the dialogue and idea formulation phase, engages participants in discussions, synthesizing insights and brainstorming to develop and refine concepts and hypotheses. The fourth step, visions, focuses on articulating clear and innovative solutions, defining objectives, sharing a conceptual framework and experimenting prototypes to guide future design decisions [

15]. In the last phase, exchanges and data manipulation are taking place among participants and invited stakeholders to question initial design ideas, to refine them, and make them evolve further. All the activities described in

Figure 1 contributed differently to the various outputs of the workshop.

The “Design Thinking & Digital Heritage Workshop” was carried out following 5 phases (field research, data processing, dialogue, visions, discussion) associated with the 5 components of the Design Thinking process, according to the IDEO Model [

14]: discovery, interpretation, ideation, experimentation, and evolution (see

Figure 1). In general, the phases were carried out in a chronological and consecutive order, but sometimes the activities naturally overlapped, hybridized, or integrated one other. For example, the site visit to the Church of San Francesco was complemented by the opportunity to observe a laser scanner survey demonstration by Prof. Mario Santana Quintero, which was a great enhancement for the students. The trip on the historical train that took the participants from Fabriano to Pergola is also an example of overlapping phases: this was not only an opportunity to discover the landscape and history of the area, but it also allowed participants to enjoy the virtual trip of the Porto–Vigo line [

16], which was displayed in a virtual gate at the Pergola Station. Moreover, it provided the opportunity to attend a second demo session of the survey techniques and to start exchanging ideas and visions on the cultural landscape the students were crossing during the train trip [

17].

The first “discovery phase” served to empathise with the territory, i.e., to get to know the project areas from different points of view, such as the historical, architectural, social, and economic ones. This was possible thanks to independent site visits and guided tours with local administrators. Living in Cagli during the workshop and talking to the local community made it even more possible to gather information on the area’s potential and criticalities, allowing students to develop a deep understanding of the problem to be addressed in the design phase. Fundamental to this phase were also the lectures given by invited professors, who guided the students in framing the problem and understanding the available tools. In particular, given the limited time and the numerous planned activities, lectures were held on the sites with a practical demonstration showing how to use technical tools and to survey at different scales, promoting a learning-by-doing process to acquire the necessary practical skills. Indeed, in layered and heritage-rich contexts, such as Cagli and Pergola, the integration of terrestrial and aerial data acquisitions is essential to gain a complete documentation and digital reconstruction of the investigated object [

18]. The 3D visualization of cultural heritage and landscapes eased the following elaboration of design scenarios [

19].

The second “interpretation phase” focused on data processing, and it was carried out in small groups under the guidance of tutors. This step enabled students both to learn how to process and manage the data obtained from the digital surveys, by means of short, targeted tutorials, and also how to elaborate and understand the observations made during the surveys: an interpretation phase that requires a critical spirit, an overall vision, and a lot of time.

In the third “ideation phase” (

Figure 2) students and teachers, gathered in mixed groups, worked on the creation of a set of ideas and related them to concrete opportunities that had been identified in the previous phase. This step focused on a dialogue between all participants involved, and it was developed with the technique of round tables of discussion. The aim of the ideation phase is thus to brainstorm potential solutions and finally to select and develop one specific one. This approach is based on participatory methods and builds specifically on the methodology of the Feral Business Clinic [

20]; it was then freely adapted to match the needs of an architectural and urban design project. In the above-mentioned methodology participants travel between desks, while desk coordinators remain in place, keeping the memory of the collaborative thinking and transferring it to the newcomers in the second and third round. In this setting we had three desks addressing the following three topics:

Desk 1—The San Francesco convent and the community: explore the former convent and its potential for the community;

Desk 2—The San Francesco convent and the touristic potential: explore the former convent and its touristic potential;

Desk 3—Pergola, the landscape, the railway, and the built heritage: explore Pergola station and the building of the former agricultural consortium next to the station.

Figure 2.

Desks of discussion, topics, and group dynamics, highlighting the outputs for each round of the “ideation phase”.

Figure 2.

Desks of discussion, topics, and group dynamics, highlighting the outputs for each round of the “ideation phase”.

The total time dedicated to the activity was two hours and thirty minutes, of which two hours are dedicated to the discussions in each desk (three discussions of forty minutes each) and fifteen minutes (occurs twice) dedicated to a recap after the exchange in order to set all participants on the same page.

Each group of travellers moves together in a single group and ends its journey in the desk/topic which will constitute its main design task afterwards. So, for example, the participants destined to elaborate a design proposal and vision for Pergola were ending their desk journey in desk 3 (

Figure 3).

Each round pursues a different goal through a different methodological tool. Particularly the three rounds consist of the following steps:

Round 1: word cloud. For the identification of values, risks, and challenges connected to the assigned topic. Participants are asked to collect words synthesizing their perceptive–interpretative analysis of the context; e.g., the values and potentials, as well as the risks and negative or critical aspects of the area, or any observation they might have gathered during and after the site visit. The word cloud helps frame the design goals; therefore, the chosen words should have a projective quality and address first project ideas and design inputs, trying to answer to the question: what could the area become?

Round 2: key concept. Focuses on objectives, strategies, and activity programs for the area of intervention. Starting from the previous word cloud, the second team of travellers groups the words into macro-themes and selects one of them to sharpen the focus on one main activity. This is decided based on what is the most promising functional program and the one with a major expectation of success. From there on, the second group of travellers develops the first ideas to be implemented in the assigned area/context.

Round 3: elegant steps. Works on operative actions, actors, and process, shrinking further the focus towards implementation phases, possible design actions, and actors that can enable the process. Possible design actions are renovation, construction, structural adjustment, re-arrangement of open spaces [

21], and a general adaptation of existing structures to meet the ecological needs of recycling the existing cultural and built heritage, which are the basic theoretical premises of the workshop. Possible actors to be involved in the different phases are the municipality, associations, artists, shop owners, the national railway company, etc.

The “ideation phase” culminates in the final presentation of each group’s results, which is a pivotal moment for synthesizing the various design decisions. This presentation facilitates the integration and coordination of ideas, laying the groundwork for transitioning to the next phase, the experimentation phase, which is meant to produce the design proposals.

2.3.2. A Comparative Analysis with Similar Cases: A Methodology to Assess the Design Thinking and Digital Heritage Approach

To investigate innovative aspects, weaknesses, and potential integrations of the RtL project, a selection of similar workshops was analysed. The identification of relevant case studies followed specific criteria to narrow the research scope. In particular, the selection was limited to the scientific communities of architectural design and representation of architecture. The study considered workshops that met the following criteria:

Targeting bachelor and master students and/or PhD candidates;

Having a duration similar to the RtL project (a maximum of one week);

Addressing topics related to built heritage and its regeneration.

This approach ensured a focused and relevant comparison, allowing for a critical assessment of the RtL project within its academic and disciplinary context. Sources for the data are derived from online research, a literature review, conference proceedings of the scientific associations of the two disciplinary fields, and materials received from colleagues of other universities that have tackled similar experiences. On the basis of these criteria, the following workshops were selected, which are discussed and analysed in more detail in the Results chapter: Hortus Lizori; Historic centre of Berat and Gjirokastra; UID 2024, Disegnare per gli Dei: Selinunte, Tempio F; Laboratory of Places 2018: History, Survey, Evolution; Abitare le distanze; CO-PROGETTARE SASSOFERRATO: Il parco creativo del Sentino; and MultipliCITY: uses, places, identities for resilient communities.

3. Results

The results chapter presents two types of findings. First, it includes the observation, commentary, and evaluation of the design outputs produced by students during the RtL project workshop. These outputs are analysed to assess their effectiveness and relevance within the framework of the project. Second, the chapter reports on the innovative learning outcomes derived from a comparative study with other summer schools. This analysis provides a broader understanding of the adopted methodology and highlights both innovative aspects and potential weaknesses. By comparing the RtL project workshop with other similar initiatives, it offers valuable insights into the methodology’s effectiveness and its potential applicability in comparable educational contexts.

3.1. Developing Experimental Regenerative Design Proposals and Evolving Them Through Exchange with Local Community

In the “experimentation phase”, starting from the actions and from the processes imagined during the third round of the desks of discussion, the students worked in groups in order to produce the required outputs, namely a presentation containing a master plan or an axonometry made with a point cloud and/or with some images taken by the drone to represent the activities’ program; a stakeholder map with the identification of possible actors to be involved in the process; and a collage that could tell the project idea, the vision, and what the students had imagined for their project area.

The aim of this phase was to allow the different desks to fully exploit all the tools and materials at their disposal, as well as the observations made during the surveys and in the ideation phase, in order to tell their idea of the future for the places that were the subject of the workshop: new functions, new architectures, and new infrastructures, but also different ways and processes of acting and financing interventions.

Group 1 presented the project PASOS: a re-imagining of San Francesco complex. This included the evaluation of the values, risks, and challenges for the San Francesco complex, as well as a careful reading of its surroundings; also, thanks to the use of panoramic images, the group to choose to transform the former convent into a school of “arts and crafts” through several operational and temporal steps, while at the same time enhancing the pedestrianization of the square in front of it and the historical centre where it is located. Even group 2, with the project “San Francesco Convent: a window through Cagli”, focused on the complex located in the historic centre, but found it more appropriate to analyse its strengths and weaknesses by a drone photo (

Figure 4). The group proposed short and long-term uses for the former convent, which could be realized in parallel with the architectural transformation of the building, with an app allowing for the consultation of activities and the booking of spaces.

Finally, group 3, with the “PERGOL-HUB” project, used both drone images and the point cloud to describe its project vision: the idea is to use both the station and the former agrarian consortium next to it to create a HUB dedicated to sustainable mobility and leisure, acting as a meeting point for citizens and an attractor for tourists (

Figure 5).

Finally, in the “evolution phase”, the envisioned projects were publicly presented to the workshop professors and the local administration. This final confrontation phase allowed the realised visions to be questioned, with the aim of improving them and bringing them ever closer to the needs of the territory, which is in line with the custom-made project vision. The administration treasured the analyses and proposals made, as well as the digital material produced; these outputs, realized through an innovative multidisciplinary approach, captured unexplored potential of the area and provided stimuli towards a more sustainable design of the city. The presentations were an important stimulus, an input, towards a public dialogue—still open—on the need for change and new planning for municipalities. The first planning proposals need to evolve in a continuous short-cycle innovation process that includes constant exchange between the administration, the local community, and the university.

In the iterative and experimental approach of Design Thinking based on the act of “doing” and the exploration of ideas through trial and error, “visual tools” are fundamental in facilitating the understanding and management of the complex and—above all—new and unexplored information that characterises the phases of the method [

22,

23]. For this reason, the images produced using ICT, capable of rendering information at different scales and details of project areas, were fundamental at the discussion desks to identify relationships and understand problems, break them down, and develop innovative and shared short- and long-term solutions.

3.2. A Comparison with Other Workshops: Innovative Aspects and Weaknesses of the RtL Project

Here are the results of comparisons between workshops like the RtL project. The first table identifies features present and absent in the analysed experiences (

Table 1), while the second describes the main activities carried out in each of them and the involved disciplines (

Table 2). These will then allow an understanding of the relationships between the “columns” and the outputs produced.

Studying and comparing the RtL project with other summer schools or similar workshops allowed us to identify and understand elements tools and methods that distinguished and made our research innovative, but also those that would be useful in the RtL project’s experience. Among them, for example, the use of a model (maquette), as was the case in the

Lizori workshop [

24], was an experience very similar to the RtL project in program, tools, and content. The presence of a model at the urban and spatial scales would have certainly facilitated the reading of the territory and its orography, allowing participants to discuss together about problems and characteristic aspects of the territory around it.

A relevant topic discussed in Summer School 2024,

Drawing for the Gods: Selinunte, Temple F [

25], also addressed the use of 3D printing. On this occasion, students were divided into working groups, each focused on specific topics such as rapid prototyping, augmented reality, equirectangular images, motion tracking, and serious games. They compared different survey technologies and methodologies, developing various proposals for reconstructive models and solutions for visualization and dissemination. The field phase and the analysis of the ruined Temple F became opportunities not only to explore the complexity of the structure and its relationship with the surrounding context, but also to propose a conjectural reconstruction [

26] (p. 328). This in-depth exploration of ICT tools did not take place within the RtL project due to time and organizational constraints. During the RtL project, the outputs focused not on new solutions for heritage visualization but on using point clouds to discuss and propose new development possibilities for Cagli and Pergola.

The

Abitare le distanze workshop [

26] didn’t employ ICTs but focused on a co-design experience with the municipal administration and the realisation of a series of boards with hand sketches and mapping, consisting of design indications offering possible visions of sustainable regeneration. Both the workshop held in the historic centres of Berat ad Gjrokastra [

27] and the workshop

Laboratory of Places 2018/19 [

28,

29]—compared with the RtL project—highlighted the need for long times to enable students to become autonomous in the use of digital surveys equipment and the consequent production of “

multimedia and versatile drawings and content, quickly usable in presentations and social media environments” [

27] (p. 164). This interdisciplinary approach, more focused on digital surveys, allowed for a more detailed study of the historical, architectural, and structural aspects of the areas under consideration. It also enabled a more accurate understanding of the built heritage, providing valuable insights for future interventions. In contrast, the RtL project dedicated less time to digital surveys, prioritizing dialogue with the local administration and community in order to propose both short- and long-term design strategies based on the surveys and co-design activities.

To further substantiate the comparison between workshops like the RtL project’s, we also included two workshops organized within the Department of Construction, Civil Engineering, and Architecture at the Università Politecnica delle Marche: the co-design workshop

Branding4Resilience (B4R) [

30], held in Sassoferrato, and the

MultipliCity workshop in Jesi [

31]. These workshops allowed for a deeper analysis of innovative and weak aspects, given our familiarity with their organization and execution.

The B4R co-design workshop in Sassoferrato shares many similarities with the RtL project: the topics covered, the design scales, the multidisciplinary approach, and the strong connection with the local territory and administration. In both workshops, co-design activities took place, but with different objectives and participants. During the RtL project workshop, the researchers were involved in all three rounds of dialogue and conception to create a foundation for imagining design visions. In contrast, the B4R workshop engaged a broader group of stakeholders in the rounds, including local associations, municipal administrators, entrepreneurs, and representatives of local public and private entities. This broader community involvement enabled workshop participants to quickly identify pressing issues in Sassoferrato, leading to faster and more concrete project development that was firmly anchored in the needs of the area. This type of engagement was not realized in the RtL project due to time constraints (which were devoted to ICT tools absent in B4R) and language barriers. In international workshops held in small communities with an older population, overcoming language and communication barriers, especially at co-design tables, must often be considered. This challenge was overcome during public presentations through the use of images, icons, collages, and 3D models. This was also the case in the MultipliCity workshop in Jesi, where Italian and Spanish students successfully communicated their project ideas to the community.

This event stemmed from an existing agreement between the university and the local municipal administration. The works produced helped stimulate ongoing projects in the architectural design studios and strengthened the bond between the city and the university. It also led to new initiatives, such as the creation of a city model and the organization of roundtable discussions with stakeholders.

4. Discussion

The workshop stemmed from an interdisciplinary approach: experts in digital cultural heritage, survey and representation techniques, geomatics, and architectural, urban and landscape designers brought together their expertise and performed a ground-breaking study activity (

Figure 6).

This approach aligns with previous research, which emphasized the use of digital technologies, particularly Virtual Reality (VR) and 3D point clouds, for analysing complex areas characterized by the coexistence of conflicting conditions and interests. The objective was to experiment with a process of integration between established methods of heritage digitization and design practices applied to cultural heritage in order to derive unexpected and successful results for the re-activation of the inner areas. This aim was achieved through the use, overlap, and dialogue of different tools and techniques (VR, digitization, architectural design, group work, stakeholder dialogue, site visits, etc.) already tested individually in this context, but in an “autonomous” way. Such a multidisciplinary approach therefore allowed the production of design visions capable of taking into consideration the typical multiple aspects of the inner areas. Given the multilayered nature of the area, which includes several archaeological and historical sites along with a varied and rich cultural landscape, interdisciplinary methodologies supported by innovative learning techniques were essential to capture all the facets and needs of the area, which otherwise would have remained in the background and would have led to a design that was not tailored to the area.

A similar multidisciplinary approach is observed in the work of Costantino et al. [

32], where digital tools were frequently employed to analyse and map natural heritage and ancient footpaths, creating a territorial trail system connecting smaller municipalities. Conversely, in the ScAR project, which views cultural heritage as a dynamic system of values shaped by local populations, the approach focused on fostering intergenerational and intercultural dialogue. In this context, ICTs supported bottom-up learning pathways and provided an opportunity for resilient social and territorial development [

33].

In our case, the effectiveness of the “melting pot” methodology—combining the teachers’ expertise with the students’ backgrounds—was proven by the results. In just a day and a half of actual work, three design solutions were developed, including strategies linked to territorial and multilevel needs analysis, with high-quality visual outputs. The diverse skills within the groups allowed for the analysis of issues from multiple perspectives, and the peer-to-peer methodology in groups with varying levels of expertise proved to be a successful strategy. While it was initially challenging to coordinate the group, the mix of competencies ultimately proved to be a winning formula. The design thinking workshop therefore faced and overcame the challenge of working in a short period of time, on a fragile and complex territory, with an international and multidisciplinary team. The results revealed its cognitive, narrative and design approach, where digital data have been part of the creative process. This is precisely the distinctive character of the RtL project, which is synthesized and further analysed in the table below, where objectives and specific learning outcomes are explained (

Table 3).

Even if not directly compared with the other workshops listed in the Results chapter, the specific skills acquired by the students highlight the innovative approach used in this teaching experience. The RtL project workshop has shown how the integration of digital technologies in academic co-design processes enables the overcoming of disciplinary barriers, fostering greater mutual understanding and a design capable of involving everyone, optimising co-creation time and producing clear and effective outputs.

One of the most innovative aspects of the workshop was the use of ICT in the Design Thinking process. If on the one hand, in fact, the use of a co-design method among researchers from different disciplinary fields, who explored the territory and dialogued with the administration and the local community, ensured solutions oriented to the real needs of the municipality of Cagli, on the other hand, the development of ideas through ICT made it possible to produce visions that were measurable and “measured” against the context of intervention.

5. Conclusions

In addition to receiving positive feedback from participants and the municipality involved in the initiative, the workshop process could be improved in some aspects and be made more effective, as emerged from the comparison with other similar activities. In particular, the collaborative thinking facilitation process during the ‘ideation phase’ might be more fruitful if managed by professional workers in this field. In fact, informed participants which are expert on the topics should focus on content-related aspects of the discussion and not on its moderation, while their presence at each desk is necessary and proved to be successful

Additionally, the data acquisition and processing phase, along with the parallel learning of the key survey tools and software, require a considerable amount of time. Students need a period to absorb and fully understand the information acquired, which may not always be feasible within a four-day intensive workshop. One potential solution could be to pre-select students who are already familiar with these tools, or alternatively, to narrow the focus of the workshop to a smaller building or artifact. This would allow more time for individual learning and practical application of the tools. Despite these areas for improvement, the workshop generated significant benefits and positive outcomes on two main levels: the territorial level and the interdisciplinary, international research and cooperation level. The innovative approach, which successfully brought together various aspects of both the territory and the disciplines involved, fostered new potential connections between the university and the local community. On one hand, the work conducted on the area enhanced understanding of the context, while also generating fresh ideas and visions for the city, ultimately benefiting the local community. On the other hand, it facilitated fruitful international cooperation for students, young researchers, and teachers.

In conclusion, thanks to this research and its application in the RtL project workshop, our approach has tested and verified how combining digital heritage and design thinking methodologies represents an effective interdisciplinary tool to produce a dialogue between research and practice, which enables more effective regeneration processes in inner territories.

Author Contributions

The authors have collaboratively contributed to the paper. In particular the authors agree on the following contributions: conceptualization R.Q., M.F. and B.D.L.; methodology, M.F. and B.D.L.; analysis B.D.L.; investigation R.Q., M.F. and B.D.L.; resources, R.Q., M.F. and B.D.L.; data curation R.Q. and B.D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Q., M.F. and B.D.L.; writing—review and editing R.Q., M.F. and B.D.L.; visualization B.D.L.; supervision, R.Q. and M.F.; project administration R.Q.; and funding acquisition, R.Q. The section attribution is as follows: Introduction, R.Q.; Material and methods: The context of intervention, Preliminary research activities framing and addressing the RtL workshop, and The use of ICT in co-design, B.D.L.; Methodology, M.F. and B.D.L.; Results, M.F. and B.D.L.; Discussion, R.Q.; and Conclusions, R.Q. and M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by “RAILtoLAND. Collaborative platform to design innovative tools for communicating European cultural landscapes from the train”, Erasmus+ Programme of EU Union, grant number KA 2019-1-ES01-KA203-065554.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The support and background of this research has been granted by the following projects: “RailtoLand. Collective ideation platform to develop innovative tools to communicate the European Cultural Landscapes”, which is an Erasmus + project, Key Action Strategic partnership, running from 2019 to 2022. The Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM); LP Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM); Université Gustave Eiffel de Paris (UGE); Universitá Politecnica delle Marche de Ancona (UNIVPM); Centro de Computaçao Grafica de Guimaraes (CCG); and the International Union of Railways (UIC). “B4R Branding4Resilience. Tourism infrastructure as a tool for the enhancement of small villages through resilient communities and new open habitats” (project number 201735N7HP) is a research project of relevant national interest (PRIN 2017-Youth Line) funded by the Ministry of University and Research (MUR) (Italy) with a three-year duration (2020–2024). The project is coordinated by Maddalena Ferretti (Università Politecnica delle Marche), and it involves as partners the University of Palermo (Barbara Lino), the University of Trento (Sara Favargiotti), and the Politecnico di Torino (local coordinator Diana Rolando). For more information:

www.branding4resilience.it, accessed on 3 December 2024. “RESETtling APPennines. Territorial promotion, valorisation of cultural heritage and transformation of the living space for a resilient rebirth of the Marche Apennines” is a PhD project financed by the MUR within the Plan “Ricerca e innovazione 2015–2017”—Axis “Capitale Umano”, of the Fund for Development and Cohesion. (Benedetta Di Leo, Maddalena Ferretti, Ramona Quattrini). UnivPM, Ancona, 17 October 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barca, F.; Casavola, P.; Lucatelli, S. Strategia nazionale per le Aree interne: Definizione, obiettivi, strumenti e governance. Mater. Uval 2014. Available online: https://www.bibliotecadigitale.unipv.eu/entities/publication/2b776642-1938-4353-a4ce-7c8c0dd4cbd7 (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Alleanza Italiana per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile. Available online: https://asvis.it/rapporto-asvis/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Marcarini, A.; Rovelli, R. Atlante Italiano delle Ferrovie in Disuso; Istituto Geografico Militare: Firenze, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Rossi, A. Riabitare l’Italia. Le Aree Interne Tra Abbandoni e Riconquiste; Progetti Donzelli: Roma, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti, M.; Di Leo, B. Making things. Practicing co-creation in the marginal territories of central Apennine. In Practices in Research #04—Beyond the Mandate; Burquel, B., Vandenbulcke, B., Fallon, H., Eds.; In Practice: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; pp. 103–127. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, A. Drosscape: Wasting land in Urban America; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas, R. Junkspace; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Renzi, F. La natura urbana dell’Appennino. Equilibri, Rivista per lo sviluppo sostenibile. La Città Contemp. 2018, 1, 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Blandino, G.; Bracalente, L.; Chiurchiù, L.; Cruciani, A.; Cucchi, E.R.; Cassandra Cianca, G.; Comparato, M.C.; Gentili, M.; Pucci, C.; Puccitelli, O.; et al. Chirocene; Hacca Edizioni: Matelica, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Amirante, R. Il Progetto Come Prodotto di Ricerca. Un’ipotesi; Letteraventidue: Siracusa, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Faliu, B.; Siarheyeva, A.; Lou, R.; Merienne, F. Design and prototyping of an interactive virtual environment to foster citizen participation and creativity in urban design. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Information Systems Development, Lund, Sweden, 22–24 August 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, S.; Schnabel, M.A. Virtual environments as medium for laypeople to communicate and collaborate in urban design. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2020, 63, 451–464. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Sepulveda, M.; Fonseca, D.; Franquesa, J.; Redondo, E. Virtual interactive innovations applied for digital urban transformations. Mixed approach. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 91, 371–381. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. Design Thinking. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Viganò, P. Territorio Dell’urbanistica. Il Progetto Come Produttore di Conoscenza; Officina: Roma, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berrocal Menárguez, A.B.; Zamorano Martín, C. El Ferrocarril Oporto-Vigo: Una Aproximación a Sus Paisajes; UAM Ediciones Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Quattrini, R.; Ferretti, M.; Berrocal, A.B.; Zamorano, C. Digital heritage&design thinking: The railtoland workshop as an innovative practice in the higher education scenario. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, 48, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Russi, N. Background. Il Progetto del Vuoto; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.; Li, W.; Lai, S.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Q. The integration of terrestrial laser scanning and terrestrial and unmanned aerial vehicle digital photogrammetry for the documentation of Chinese classical gardens—A case study of Huanxiu Shanzhuang, Suzhou, China. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 33, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windhager, F.; Federico, P.; Schreder, G.; Glinka, K.; Dörk, M.; Miksch, S.; Mayr, E. Visualization of cultural heritage collection data: State of the art and future challenges. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2018, 25, 2311–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzenbaumer, B. Community economies: A practice exchange. Alp. Community Econ. Lab. Snapshot J. 2020, 1. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10863/17124 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Gill, C.; Merce, G. Teaching design thinking: Evolution of a teaching collabortion across discipinary, academic annd cultural boundaries. In Proceedings of the 18th International Confeence on Engineering and Product Desgn Education: Collaboration and Cross-Disciplinaraity, Aalborg, Denamrk, 8–9 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mendel, J.; Yaeger, D. Knowledge Visualization in Design Practice: Exploring the Power of Knowledge Visualization Problem Solving. Parsons J. Inf. Mapp. 2010, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bianconi, F.; Filippucci, M.; Zagari, F.; Clemente, M.; Meschini, M. (Eds.) Hortus Lizori: Percorsi Sulla Rappresentazione del Paesaggio e la Valorizzazione del Patrimonio Storico Culturale; Maggioli Editore: Rimini, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zerlenga, O. UIDSS2024_UID_Summer School 2024, Drawing for the Gods: Selinunte, Temple F. Diségno 2024, 15, 328–330. [Google Scholar]

- Cervasato, A. Abitare le distanze. In Transizioni. L’avvenire della didattica e della ricerca per il progetto di architettura. In Proceedings of the Nono Forum ProArch, Cagliari, Italy, 18–19 November 2022; pp. 1055–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Verdiani, G.; Dipasquale, L.; Merlo, A.; Carta, M. Historic Centres of Berat and Gjirokastra, Albania. In From Vernacular to World Heritage, 1st ed.; Dipasquale, L., Mecca, S., Correia, M., Eds.; Firenze University Press: Firenze, Italy, 2021; pp. 160–177. [Google Scholar]

- Fanzini, D.; Achille, C.; Tommasi, C. Attivare i luoghi della cultura per favorire la ricerca e l’innovazione socialmente responsabile. Techne 2021, 21, 327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Achille, C.; Fiorillo, F. Teaching and Learning of Cultural Heritage: Engaging Education, Professional Training, and Experimental Activities. Heritage 2022, 5, 2565–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, M.; Di Baldassarre, M.G.; Di Leo, B.; Rigo, C. Co Progettare Sassoferrato. Il Parco Creativo del Sentino. In Branding4Resilience Atlante. Ritratto di Quattro Territori Interni Italiani; Ferretti, M., Favargiotti, S., Lino, B., Rolando, D., Eds.; LetteraVentidue: Siracusa, Italy, 2024; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Mondaini, G.; Ferretti, M.; Bonvini, P.; Cellini, G.R.; Chiacchiera, F.; Leoni, S.; Di Leo, B.; Moretti, L. Molteplicittà in Le Parole e le Forme. In Proceedings of the Decimo Forum ProArch, Genova, Italy, 16–18 November 2023; pp. 864–865. [Google Scholar]

- Costantino, C.; Mantini, N.; Benedetti, A.C.; Bartolomei, C.; Predari, G. Digital and territorial trails system for developing sustainable tourism and enhancing cultural heritage in rural areas: The case of San Giovanni Lipioni, Italy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casonato, C.; Vedoà, M.; Cossa, G. Discovering the Everyday Landscape: A Cultural Heritage Education Project in the Urban Periphery; LetteraVentidue Edizioni: Siracusa, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).