From Data to Impact: Assessing the Value of Cultural Heritage in the Digital Age

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Digital Transformation and Data Policies

3.2. Managing Digital Change Responsibly: Key Concepts

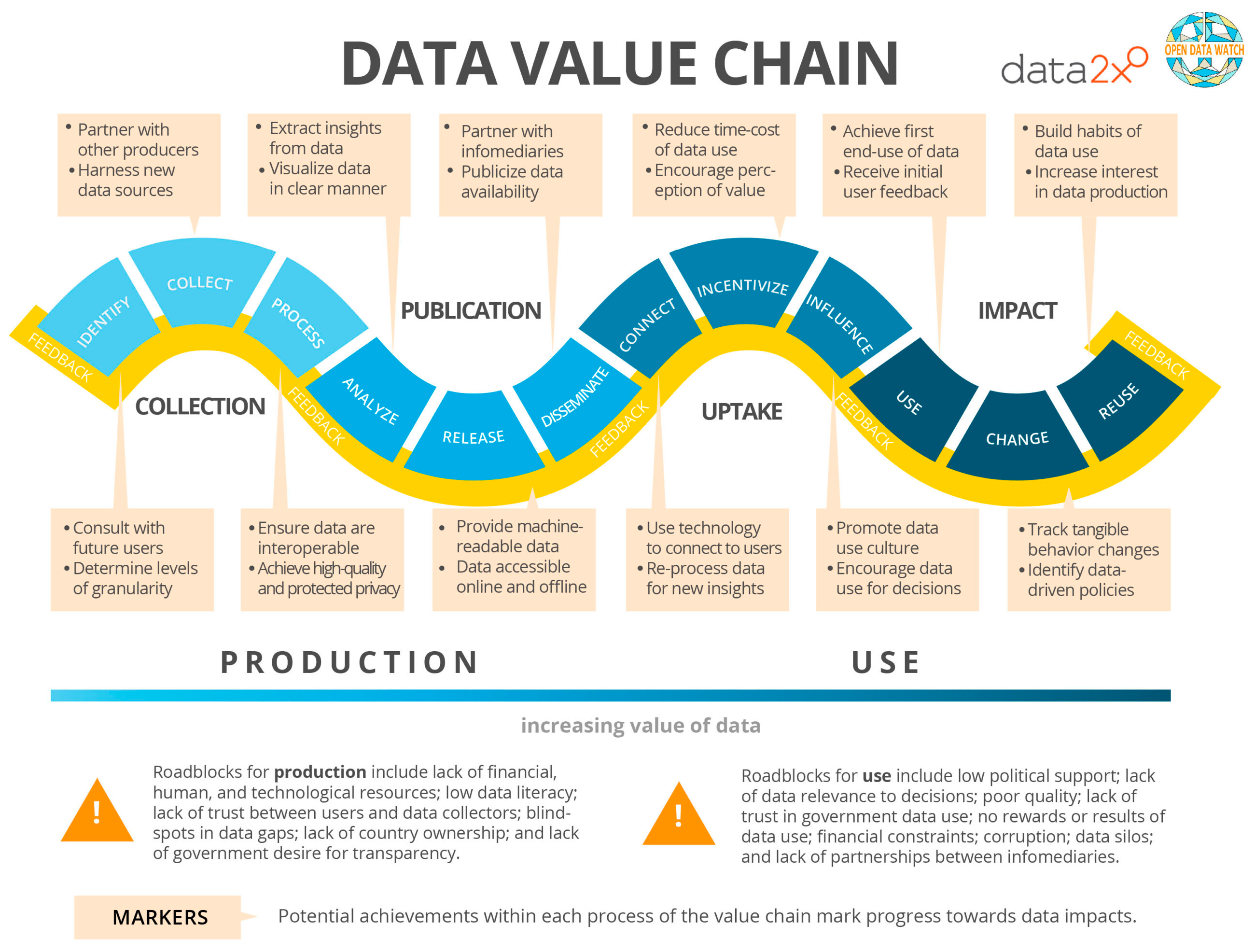

3.3. From Digitalization to Impact: Approaches and Challenges

3.4. Exploring EU Initiatives for Impact Assessment and the Challenges of Measurement

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LAM | Libraries, archives, museums |

| EU | European Union |

| DARIAH | Digital research infrastructure for the arts and humanities |

| IA | Impact assessment |

| BVI | Balanced value impact |

| SoPHIA | Social platform for holistic heritage impact assessment |

| MOI | Museums of impact |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

References

- Hvenegaard Rasmussen, C.; Rydbeck, K.; Larsen, H. (Eds.) Libraries, Archives, and Museums in Transition: Changes, Challenges, and Convergence in a Scandinavian Perspective, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breathnach, C.; Margaria, T. Digital Humanities and Cultural Heritage in AI and IT-Enabled Environments. In Bridging the Gap Between AI and Reality. AISoLA 2023; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Steffen, B., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.; Heravi, B. Linked Data and Cultural Heritage: A Systematic Review of Participation, Collaboration, and Motivation. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2021, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasovac, T.; Chambers, S.; Tóth-Czifra, E. Cultural Heritage Data from a Humanities Research Perspective: A DARIAH Position Paper; 2020. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-02961317/document (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Navarrete, T. Crowdsourcing the Digital Transformation of Heritage. In Digital Transformation in the Cultural and Creative Industries. Production, Consumption and Entrepreneurship in the Digital and Sharing Economy; Massi, M., Vecco, M., Lin, Y., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Olivieri, M. Cultural Heritage on Social Media: The Case of the National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo Da Vinci in Milan. In Digital Transformation in the Cultural and Creative Industries. Production, Consumption and Entrepreneurship in the Digital and Sharing Economy; Massi, M., Vecco, M., Lin, Y., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, Y.; Xie, J. The Evolution of Digital Cultural Heritage Research: Identifying Key Trends, Hotspots, and Challenges through Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego, À. Measuring the Impact of Digital Heritage Collections Using Google Scholar. Inf. Technol. Libr. 2020, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E.F. Making Digitization Count: Assessing the Value and Impact of Cultural Heritage Digitization. Proc. IS&T Arch. 2016, 13, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foresta, D.; Mergier, A.; Serexhe, B. The New Space of Communication, the Interface with Culture and Artistic Activities; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Uzelac, A. How to Understand Digital Culture: Digital Culture—A Resource for a Knowledge Society? In Digital Culture: The Changing Dynamics; Uzelac, A., Cvjetičanin, B., Eds.; Institut za razvoj i međunarodne odnose (IRMO): Zagreb, Croatia, 2008; pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Uzelac, A.; Obuljen Koržinek, N.; Primorac, J. Access to Culture in the Digital Environment: Active Users, Re-use and Cultural Policy Issues. Medijska Istraživanja 2016, 22, 87–113. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation (EU) 2021/1970 of 10 November 2021 on a Common European Data Space for Cultural Heritage. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32021H1970 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Kuzman Šlogar, K.; Žugić Borić, A. (Eds.) Digital Humanities & Heritage; Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research: Zagreb, Croatia, 2024; Available online: https://www.ief.hr/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DHH-proceedings_PDF.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- EIF-KEA. Market Analysis of the CCs in EUROPE. 2021. Available online: https://keanet.eu/wp-content/uploads/ccs-market-analysis-europe-012021_EIF-KEA.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Drabczyk, M.; Dimou, A.; de Koning, J.; Mafredini, F.; Svorc, J.; Peeters, R. Comprehensive Guide of the Benefits, Opportunities, Risks and Gaps in the Management of Cultural Heritage Digitisation; REEVALUATE, a European Union Horizon Research and Innovation Programme, 2024. Available online: https://reevaluate.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/REEVALUATE-D1.1-Comprehensive-guide-of-the-benefits-opportunities-risks-gaps-in-the-management-of-CH-digitisation_final.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Finnis, J.; Kennedy, A. Guide to Digital Transformation in Cultural Heritage Building Capacity for Digital Transformation Across the Europeana Initiative Stakeholders. 2022. Available online: https://digipathways.co.uk/resources/guide-to-digital-transformation-in-cultural-heritage/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Valtysson, B.; Kjellman, U.; Audunson, R. The Impact of Digitalization on LAMs. In Libraries, Archives, and Museums in Transition: Changes, Challenges, and Convergence in a Scandinavian Perspective; Hvenegaard Rasmussen, C., Rydbeck, K., Larsen, H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Uzelac, A.; Primorac, J.; Lovrinić Higgins, B. Digital Cultural Policy in Croatia. Searching for a Vision. In Digital Transformation and Cultural Policies in Europe; Hylland, O.M., Primorac, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Open Data. An Engine for Innovation, Growth and Transparent Governance. COM(2011) 882 Final, 2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0882:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Directive (EU) 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on Open Data and the Re-Use of Public Sector Information (Recast). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019L1024 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Directive (EU) 2019/790 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on Copyright and Related Rights in the Digital Single Market and Amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2019/790/oj (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- European Commission. European Strategy for Data. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0066 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Hoskins, A. 29. The Mediatization of Memory. In Mediatization of Communication; Lundby, K., Ed.; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurro, C.; Plets, G.; Verheul, J. Digital Heritage Infrastructures as Cultural Policy Instruments: European and the Enactment of European Citizenship. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2023, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliacani, M.; Toscano, V. Accounting for Cultural Heritage Management. Resilience, Sustainability and Accountability; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.E.; Lamm, E. Legitimacy and Organizational Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 191–203. [Google Scholar]

- IEAG. A World that Counts: Mobilising the Data Revolution for Sustainable Development; The United Nations Secretary-General’s Independent Expert Advisory Group on a Data Revolution for Sustainable Development. 2014. Available online: http://www.undatarevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/A-World-That-Counts.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Holtorf, C. Embracing Change: How Cultural Resilience Is Increased Through Cultural Heritage. World Archaeology. 2018, 50, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Brundtland Commission. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; UN-Dokument A/42/427; UN: Geneva, Switzerland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- SoPHIA Consortium. Deliverable D3.1: Toolkit for Stakeholders; 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5e8f01916&appId=PPGMS (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Finnis, J.; Kennedy, A.; The Digital Transformation Agenda and GLAMs. A Quick Scan Report for Europeana Culture24. 2020. Available online: https://pro.europeana.eu/files/Europeana_Professional/Publications/Digital%20transformation%20reports/The%20digital%20transformation%20agenda%20and%20GLAMs%20-%20Culture24%20findings%20and%20outcomes.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Navarrete, T. Chapter 12: Digital Cultural Heritage. In Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage; Rizzo, I., Mignosa, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 251–271. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, S. Delivering Impact with Digital Resources: Planning Strategy in the Attention Economy; Facet Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, D.E.; Punzalan, R.L.; Leopold, R.; Butler, B.; Petrozzi, M. Stories of Impact: The Role of Narrative in Understanding the Value and Impact of Digital Collections. Arch. Sci. 2015, 16, 327–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, S.; Deegan, M. Measuring the Impact of Digitized Resources: The Balanced Value Model. In Proceedings of the 2013 Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHeritage), Marseille, France, 28 October–1 November 2013; pp. 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, K. Exploring Digital Libraries: Foundations, Practice, Prospects; Facet Publishing: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, J.; Tanner, S. Impact Assessment Indicators for the UK Web Archive. Perform. Meas. Metr. 2021, 23, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partidário, M.; den Broeder, L.; Croal, P.; Fuggle, R.; Ross, W. Impact Assessment; International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA): Fargo, ND, USA, 2012; Available online: https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/eia/documents/WG2.1_apr2012/Fastips_1_What_is_IA.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Court, S.; Jo, E.; Mackay, R.; Murai, M.; Therivel, R. Guidance and Toolkit for Impact Assessments in a World Heritage Context; UNESCO. 2022. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidance-toolkit-impact-assessments/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Tišma, S.; Uzelac, A.; Franić, S. Cjelovita Procjena Učinka Intervencija u Području Kulturne Baštine—SoPHIA Model; Jesenski i Turk: Zagreb, Croatia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Chapter 23: Assessment of Value in Heritage Regulation. In Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage; Rizzo, I., Mignosa, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 456–469. [Google Scholar]

- Beel, D.; Wallace, C.D. Gathering Together: Social Capital, Cultural Capital and the Value of Cultural Heritage in a Digital Age. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2018, 1, 697–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnis, J.; Chan, S.; Clements, R. How to Evaluate Online Success? A New Piece of Action Research. In Museums and the Web 2011: Proceedings; Trant, J., Bearman, D., Eds.; Archives & Museum Informatics: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011; Available online: https://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2011/papers/how_to_evaluate_online_success_a_new_piece_of_.html (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Tanner, S. Measuring the Impact of Digital Resources: The Balanced Value Impact Model. 2012. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/30677096.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Tanner, S. Europeana—Core Service Platform. MILESTONE EMS26: Recommendation Report on Business Model, Impact and Performance Indicators. 2016. Available online: https://pro.europeana.eu/files/Europeana_Professional/Projects/Project_list/Europeana_DSI/Milestones/europeana-dsi-ms26-recommendation-report-on-business-model-impact-and-performance-indicators-2016.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Tanner, S. Using Impact as a Strategic Tool for Developing the Digital Library via the Balanced Value Impact Model. Libr. Leadersh. Manag. 2016, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Europeana Foundation. Europeana Impact Playbook Phase One: Impact Design. 2017. Available online: https://europeana.atlassian.net/wiki/spaces/CB/pages/2256928797/Phase+one+-+Impact+design (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Europeana Foundation. Europeana Impact Playbook Phase Two: Assess. 2020. Available online: https://europeana.atlassian.net/wiki/spaces/CB/pages/2256699694/Phase+two+-+Impact+measurement (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Europeana Foundation. Europeana Impact Playbook Phase Three. 2021. Available online: https://europeana.atlassian.net/wiki/spaces/CB/pages/2256568350/Phase+three+-+Impact+narration (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Europeana Foundation. Europeana Impact Playbook Phase Four, V.1. 2022. Available online: https://europeana.atlassian.net/wiki/spaces/CB/pages/2256961569/Phase+four+-+evaluation (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Tartari, M.; Manfredini, F.; Pilati, F.; Sacco, P.L. Change Impact Assessment Framework; inDICEs, a European Union Horizon Research and Innovation Programme: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, P.L.; Ferilli, G.; Tavano Blessi, G. From Culture 1.0 to Culture 3.0: Three Socio-Technical Regimes of Social and Economic Value Creation through Culture, and Their Impact on European Cohesion Policies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEMO. New Tool Moi Framework Helps Museums Increase Their Social Impact. 2022. Available online: https://www.ne-mo.org/news-events/article/new-tool-moi-framework-helps-museums-increase-their-social-impact/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- MOI (Museums of Impact). Facilitator’s Guidelines. 2022. Available online: https://www.ne-mo.org/fileadmin/Dateien/public/Partner_Projects/2019-2022_MOI_Framework/MOI-Guidelines_for_facilitators.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Marchiori, M.; Anastasopoulos, N.; Giovinazzo, M.; Mc Quaid, P.; Uzelac, A.; Weigl, A.; Zipsane, H. An Innovative Holistic Approach to Impact Assessment of Cultural Interventions: The SoPHIA Model. Econ. Della Cult. Spec. Ed. 2021, XXXII, 110. [Google Scholar]

| DATABASE | Impact of Digital Cultural Heritage | Evaluation of Digital Cultural Heritage | IA Framework for Cultural Heritage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total vs. relevant results according to the used keywords | |||

| Google Scholar | 40/7 | 24/1 | 2/0 |

| Zenodo | 20/1 | 16/0 | 0 |

| OpenAIRE | 73/1 | 44/0 | 16/0 |

| Platform scite.ai | 8/2 | ||

| OVERVIEW OF THE FRAMEWORKS FOR (DIGITAL) HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENTS |

|---|

| BVI—BALANCED VALUE IMPACT MODEL |

| DESCRIPTION One of the first models that challenges cultural heritage organisations to be more “evidence based” and to measure the impact of their digital resources is the balanced value impact (BVI) model developed by Simon Tanner [34,38,45,46,47]. The BVI model is focused on identifying the change in a community that arose from the existence of digital resources that are proven to be of value to the community [34]. Specially designed for cultural heritage institutions and their digital resources, it provides a conceptual framework that comprises a five-stage process guiding the IA. The BVI model distinguishes itself through its five value lenses. These lenses are specifically designed to capture the diverse types of value commonly associated with digital cultural heritage experiences. The five value lenses are the utility lens, the existence lens, the legacy lens, the learning lens, and the community. |

| SPECIFIC THEMATIC FOCUS NO |

| PROPOSED STEP-BY-STEP METHODOLOGY YES—a five-stage process guiding the IA. 1. Set the context; 2. Design the framework; 3. Implement the framework; 4. Narrate the outcomes and results; 5. Review and respond. |

| PROPOSED INDICATORS NO |

| EUROPEANA IMPACT PLAYBOOK |

| DESCRIPTION The BVI model has been further promoted, adapted and applied by the Europeana community. Based on BVI, the Europeana Impact Playbook (2017–2022) aims to help heritage organisations in their own impact planning and assessment by providing a step-by-step method to assess the impact of their digital resources consisting of four phases: 1. Designing the impact (figuring out which information is valuable for the organisation); 2. gathering data; 3. narrating and sharing the story; and 4. evaluating [48,49,50,51]. To encourage the use of the playbook, additional training and resources have been provided to Europeana users. Europeana highlights that the “Europeana Impact Community” has been active in creating a platform for learning and discussion around the impact issues and its community of professionals interested in the impact of cultural heritage has significantly increased in recent years. Sources: https://europeana.atlassian.net/wiki/spaces/CB/overview?homepageId=2256699653 (accessed on 11 February 2025) https://pro.europeana.eu/page/webinars#impact (accessed on 10 December 2024) |

| SPECIFIC THEMATIC FOCUS NO |

| PROPOSED STEP-BY-STEP METHODOLOGY YES—four-step method, each described in the related toolkit. 1. Designing the impact; 2. Gathering data; 3. Narrating and sharing the story; 4. Evaluating to increase the impact and develop new ideas for improvement |

| PROPOSED INDICATORS NO |

| CHANGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORK |

| DESCRIPTION The change impact assessment framework has been created within inDICEs, a Horizon 2020 project that aimed to help cultural heritage professionals, practitioners, and policy-makers understand the social and economic impact of digitisation [52]. Based on the Culture 3.0 theory [53] and backed by ample research, its conceptual map “the 8 Impact Areas of active digital cultural participation” is assisting cultural heritage institutions to understand the potential impact of active digital cultural participation across eight areas of impact. This framework does not include the methodology for cultural heritage organisations to use when assessing the impact of their digital resources or projects, but rather addresses the areas in which digital culture has an impact. However, it includes a set of exemplary indicators that help the measurement of impact in specific areas. The framework can offer a new perspective on designing digital cultural activities that benefit participants’ mental health, environment, and creativity. |

| SPECIFIC THEMATIC FOCUS Eight impact areas: 1. Innovation and knowledge; 2. Welfare and well-being; 3. Sustainability and environment; 4. Social cohesion; 5. New forms of entrepreneurship; 6. Learning society; 7. Collective identity; 8. Soft power. |

| PROPOSED STEP-BY-STEP METHODOLOGY NO—It provides references to other existing methodologies that could be applied. |

| PROPOSED INDICATORS YES—a set of exemplary indicators |

| IMPACTOMATRIX |

| DESCRIPTION To assess how digital tools and infrastructure in the digital humanities influence research practices across the humanities and other disciplines, the Impactomatrix identifies key impact factors and success criteria for evaluating projects in the arts and humanities. It explores the value these tools bring to the scientific community and how to maximize the efficiency of funding allocation. By analysing these impacts, the digital humanities community is expected to be able to enhance visibility and transparency, effectively communicate their benefits to researchers and funding bodies, and strengthen the role of digital research in the humanities. Through its interactive website, Impactomatrix provides a methodological framework for evaluating developments in the digital humanities, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative criteria in the assessment process. Source: https://dariah-de.github.io/Impactomatrix/ (accessed on 16 February 2025) |

| SPECIFIC THEMATIC FOCUS A selection of 21 impact areas is provided, as follows: External impact; education; data security/safety; dissemination; effectivity; efficiency; funding perspective; innovation; integration; coherence; collaboration; communication; transfer of expertise; sustainability; usage; publications; relevance; reputation; transparency; competitiveness; transfer of knowledge. Each impact area is provided with a list of corresponding factors that influence that specific area. |

| PROPOSED STEP-BY-STEP METHODOLOGY NO |

| PROPOSED INDICATORS YES. A list of ‘criteria’ is proposed to help measure changes within the chosen impact area. |

| MOI FRAMEWORK |

| DESCRIPTION The Creative Europe project, through the impact MOI! Museums of Impact (2019–2022), has developed the MOI framework—especially designed for museums in order “to help museums discuss, evaluate, and choose development goals to increase their impact in society” [54,55]. It is focused on the societal impact of museums, which also includes the digital component (digital engagement) as an important part of the whole framework. The MOI Framework consists of eight modules, which contain 151 impact statements that the framework asks the participants to evaluate. The modules are divided between enabler and impact modules. Source: https://www.ne-mo.org/resources/moi-self-evaluation-tool (accessed on 2 February 2025) |

| SPECIFIC THEMATIC FOCUS Enabler Modules: 1. What we do—impact goals and strategy; 2. How we work—organisational culture and competences; 3. How our organisation functions—resources and service development; 4. How we embed digital into services and processes—digital engagement. Impact Modules: 1. Communities and shared heritage; 2. Relevant and reliable knowledge; 3. Societal relevance; 4. Sustainable organisations and societies. |

| PROPOSED STEP-BY-STEP METHODOLOGY YES—it provides self-evaluation workbooks for each module. |

| PROPOSED INDICATORS NO |

| SoPHIA MODEL |

| DESCRIPTION The H2020 project, SoPHIA—the social platform for holistic heritage impact assessment —developed a comprehensive model for evaluating the impact of heritage interventions on the development of communities. This model responds to the need for a comprehensive, multidimensional approach in heritage project assessments, considering social, cultural, economic, and environmental factors. The project had aligned with the EU’s strategic goals of promoting sustainable and inclusive growth, recognizing cultural heritage as a key resource for resilience and innovation [31,56]. The model is structured along three axes: (1) time—assessing impacts of heritage interventions before, during, and after interventions; (2) stakeholders—ensuring inclusive participation; (3) domains—integrating multidisciplinary perspectives for evaluating the social, cultural, economic, and environmental impacts of heritage projects. The model is divided into six main areas of impact, i.e., themes of assessment that need to be considered when assessing cultural heritage interventions. Each theme is further divided into several subthemes accompanied by a proposed list of possible indicators that support the IA analysis and a list of guiding questions for qualitative analysis and stakeholder input. By including both qualitative and quantitative indicators, the model provides a framework for measuring the effectiveness of heritage projects in contributing to social cohesion, cultural diversity, economic growth, and environmental sustainability. Source: https://shorturl.at/EYZB3 (accessed on 3 February 2025) |

| SPECIFIC THEMATIC FOCUS Six assessment themes/twenty-eight subthemes (1) Social capital and governance, (2) Identity of place, (3) Quality of life, (4) Education, creativity, and innovation, (5) Work and prosperity, (6) Protection. Each theme is further divided into subthemes (28 in total) |

| PROPOSED STEP-BY-STEP METHODOLOGY YES—a Toolkit which explains the purpose, logic, and conceptual framework of the SoPHIA model and describes its implementation phases. |

| PROPOSED INDICATORS YES—a proposed list of possible indicators and a list of guiding questions for qualitative analysis and stakeholders’ inputs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uzelac, A.; Lovrinić Higgins, B. From Data to Impact: Assessing the Value of Cultural Heritage in the Digital Age. Heritage 2025, 8, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8040117

Uzelac A, Lovrinić Higgins B. From Data to Impact: Assessing the Value of Cultural Heritage in the Digital Age. Heritage. 2025; 8(4):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8040117

Chicago/Turabian StyleUzelac, Aleksandra, and Barbara Lovrinić Higgins. 2025. "From Data to Impact: Assessing the Value of Cultural Heritage in the Digital Age" Heritage 8, no. 4: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8040117

APA StyleUzelac, A., & Lovrinić Higgins, B. (2025). From Data to Impact: Assessing the Value of Cultural Heritage in the Digital Age. Heritage, 8(4), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8040117