1. Introduction: Value, Evaluation, Assessor, and Assessment Tool

In the theories and practices of heritage management, the idea of

value seems to be of capital importance both in the scientific literature and in the professional discourse of the various designers and users of heritage—so much so that all actions to develop the built environment inherited from past generations seem to depend on the

value it has been assigned. Thus, de la Torre and Mason [

1] (p. 3) start from the idea that “Value has always been the reason underlying heritage conservation”. They go so far as to assert that “It is self-evident that no society makes an effort to conserve what it does not value”.

But to characterise heritage based on a conceived value is not so easy unless we first clearly define (1) what we mean by the value of a heritage object; (2) the criteria upon which an assessor assigns this value; (3) which assessment tool can help the assessor weight the values; and (4) the evaluation process through which the value is determined. If we start from the principle that any evaluation of an object is made by positioning that object in relation to a system of values, it quickly becomes apparent that the question of heritage valuation is multifaceted: the value of an object can be attributed according to an overall analysis or on the basis of one of its constituent characteristics; it can be evaluated in light of another value, or because it promotes one value over another. In other words, the value of an object can be established by comparison, from the point of view of a particular characteristic (for example, how does one compare the aesthetic qualities of two buildings?), or one aspect of an object can be valued in comparison with another deemed less important (for example, can one argue that the ecological value of a building is more important than its symbolic value?). Similarly, how can one explain the differing interpretations offered by different assessors or the variety of evaluation processes implemented by the rule-of-law institutions of heritage management?

In the present essay, several hypotheses are developed: (1) the heritage assessment of a monument requires the study of the general context in which it is situated, as well as a combined analysis of its physical constitution (material dimension) and its sociocultural identity (immaterial dimension); (2) the many value typologies successively established by heritage experts present different conceptual distinctions and hierarchies, but the values they propose address the same questions, making them essential tools for objectifying heritage evaluation; (3) the search for the definition of a heritage object (an outcome) is complemented by the examination of the general dynamics of patrimonialisation (a process); and (4) based on the previous three hypotheses, the concepts of value, evaluator, value typology, and heritage assessment are examined together from the perspective of the dynamics of the heritage assessment process to determine how to make an assessment process as objective as possible at a given time.

The methodological approach proposed takes into consideration (1) the subjective dimension of human cognition inherent in the definitions and use of values during studies and projects carried out by actors in built heritage (users, designers, restorers, institutions, etc.) and (2) the multifaceted and evolving character of this type of process through the lens of multiple domains (history, society, philosophy, architecture, etc.).

The final conclusion conceptually describes the heritage assessment process supported by a heritage value grid based on a constructivist approach.

2. Enlightenment Economics, Aesthetics, and Ethics

Ancient initiatives exist to distinguish buildings of value. For example, the list of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, drawn up as early as the third century BC, subjectively valued Hellenistic culture by combining historical facts, symbolic codes, and myths. However, the immediate predecessor of nineteenth-century theories of heritage appeared as a continuation of the Age of Reason, which revealed the presumed ability of the

cogito to objectively analyse the world [

2]. In the eighteenth century, by leveraging the Cartesian subject–object distinction, Enlightenment scholars believed they could rationally evaluate various phenomena. The word

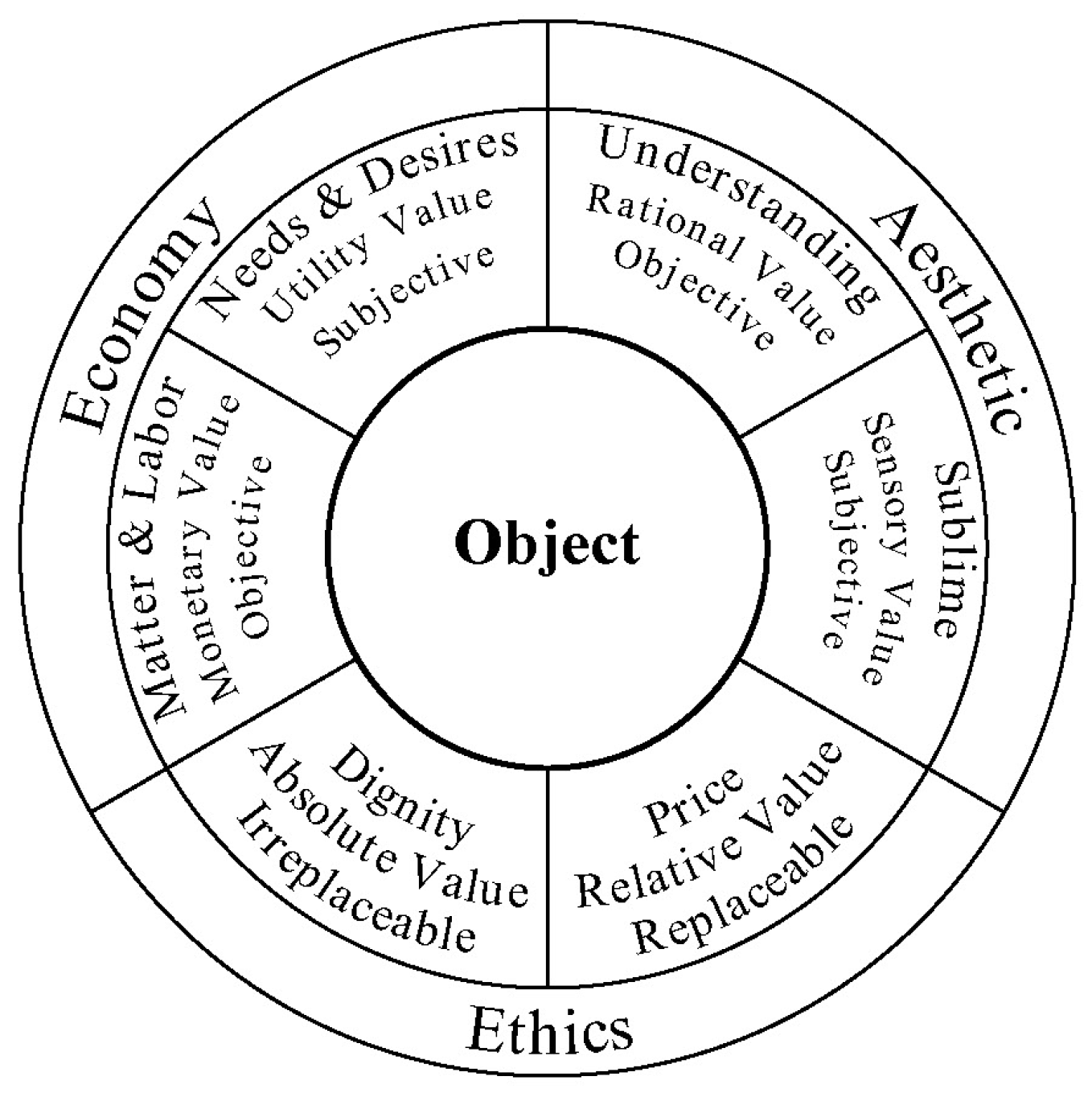

value and its derivatives are therefore mainly used in discourses formulated within three dimensions: economic, aesthetic, and ethical (

Figure 1).

(1) From an

economic point of view, a thing’s

value is not the same as its

price. Generally speaking, there are two approaches to this. Although the value of money is the result of consensus, the

objective approach establishes a price corresponding to the value of a thing independently of the observer by evaluating the thing’s conditions of production or by measuring the labour hours necessary for its production—its

labour value [

3,

4,

5]. The

subjective approach, on the other hand, determines the value of a thing by means of a psychological evaluation process, such as the

usefulness of the thing produced [

6,

7]. Utility is the ability of a thing to meet a consumer’s needs and provide well-being or satisfaction. Thus, when a building is considered from an economic point of view as a heritage

asset, it is valued

objectively in terms of the price to be paid (monetary value) or the number of hours of work required to build or maintain it (labour value), but also

subjectively from the point of view of the gains and losses attributed by the user in relation to a need to be met or to a desired form of well-being (utility value).

(2) The appearance in the salons of the first art critics drove the study of the

aesthetic value of artworks [

8,

9,

10]. While the Cartesian tradition set aside the artistic dimension in favour of a rationalism that revived Neoplatonic concepts, scholars established a

science of beauty or

critique of taste. Burke [

11] developed the empiricist theory of the sublime by replacing the classical definition of

beauty, based on a harmonious relationship between the whole of a work and its parts, with an analysis of the pleasure and displeasure the work provokes. In his attempt to unite rationalism and empiricism, Kant [

12] criticised and developed the theory of the sublime in his

Critique of Judgment. He revealed the

impure beauty of art, asserting that judging the beauty of a thing is not a matter of understanding (the logic of objective reasoning from concepts), but of the pleasure or displeasure the work inspires (the subjectivity of sensibility). In his view, a purely aesthetic judgement must be made in a contemplative way, unconcerned with the work’s usefulness. He adds that, given the constraints of its materiality and the programmatic purposes attributed to it, architecture as a work of art struggles to achieve “free beauty”; it is almost always a “dependent beauty”. Then, in his

Lectures on Aesthetics (1818–1829), Hegel [

13] describes architecture as a material negative, sensitive and non-expressive, dependent on its function and physical constraints, a raw form from which the other arts must extract themselves through dematerialisation and expressivity, accompanying the human being in his quest for the “absolute spirit”: the arts experience architecture as a burden! In other words, architecture articulates two worlds: the world of objective material constraints based on the building’s function and the world of subjective symbolisations based on the human aspirations it expresses.

(3) In terms of

ethics, in

Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, Kant [

14] distinguishes two types of value: the “price” of a thing (a thing’s “relative value”, either exchange or affective, that can be replaced by something equivalent) and the “dignity” of a thing (an “intrinsic value” that cannot be replaced by anything else in an equivalent way). When, in practice, human beings act out of moral duty (by aiming for objective moral values that establish the principle of action as a universal law), their “autonomy” therefore gives them a

priceless “dignity”. In

On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche [

15] criticises this projection of objective existence onto moral values, as if they existed

outside us because they reduce human beings’ “will” and “freedom”. He brings morality back

inside us via

evaluation (any procedure devised to determine the moral value of a thing)—not to relativise moral values, but to grasp the

will at work in them. To determine the moral value of a thing, it is thus not value itself that governs the evaluation, but our evaluation that establishes value.

Through these three points of view, as Enlightenment thinkers freed themselves from metaphysical narratives or the dogmatic authority of religious institutions, they justified the expression of their subjectivity through the autonomy of thought. Moreover, by recognising the existence of both quantitative and qualitative criteria to define it, the value of architecture became determinable through a multi-criteria analysis. This hygiene-obsessed and industrial era also saw the emergence of new materials, new construction techniques, and new public programmes. As a result, planned demolition operations appeared because it was easier and cheaper to demolish and replace old buildings that were becoming obsolete. Against this backdrop, the importance of heritage was recognised and sanctified using axiological theories.

3. From Philosophical Axiology to the Axiology of Heritage

The question of economic, aesthetic, and ethical value was raised at the beginning of the nineteenth century. The economic dimension was seemingly dismissed until the neoclassical school of thought reintroduced the concept of utility at the end of the nineteenth century, this time combined with that of marginal thinking (the value–utility of an object decreases when the number of objects consumed increases). While speculative idealism collapsed after Hegel’s death, philosophy was discredited because it seemed incapable of responding to the social and political problems of the time.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the value attributed to the

material of the heritage object was central to discussions about defining what

restoration should be. It takes on a

sacred character when Ruskin [

16] (

vi, 10) considers its unique and irreplaceable nature as a testament to the craftsmanship and labour of past generations. In contrast to the museological values in Continental Europe, it takes on a

social value when Morris [

17] (pp. 1353–1354) asserts that old monuments are “as part of the furniture” of “our daily life”. Choay [

18] (pp. 114–116) describes the debate as opposing what she calls the “piety value” emphasised by Ruskin’s moral and respectful approach to the “militant interventionism” of Viollet-le-Duc. In

The Lamp of Memory, the former associated restoration with “the most total destruction which a building can suffer” [

16] while in the article “Restoration” in his

Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du xie au xvie siècle [

19], the latter states that “To restore an edifice is not to maintain, repair or rebuild it, but to reestablish it in a complete state, that perhaps may never have existed at a given moment” [

20] (p. 11). At the end of the nineteenth century, Viollet-le-Duc’s “doctrine” [

18] was challenged by advances in archaeology and art history. Heritage actors therefore proposed more nuanced interventions. The Ruskin/Viollet-le-Duc conflict was overcome when Boito [

21] proposed a subtle synthesis drawing on the “best of each” [

18]. He defended Ruskin’s “authenticity” (his respect for the preserved original material) while agreeing with Viollet-le-Duc that the legitimacy of restoration was affirmed by its inauthenticity. He also denounced the equal treatment given to monuments from different periods and styles, stating that “in architectural monuments one or the other of the following three qualities prevails: archaeological importance, picturesque appearance, architectural beauty” [

22] (p. 75). This led him to propose three intervention types: “archaeological restoration” for monuments of Antiquity; “picturesque restoration” for Gothic architecture; and “architectural restoration”. The concepts of “authenticity, hierarchy of interventions, restorative style” therefore enabled Boito to “lay the critical foundations of restoration as a discipline” [

18]. Initially regarded as an absolute value according to Ruskin, the ancient material is now considered in relation to the other qualities of the monument. Boito laid the foundations for what would become the monumental values set out ten years later by Riegl.

At the end of the nineteenth century, German philosophers working in a neo-Kantian vein worried about Hegelian dogmatism and returned to Kant’s original criticism, introducing the term

axiology to designate a theory of values [

23]. Axiology comprises two areas of the value scale [

23,

24]: aesthetics (appreciation of what is beautiful or ugly) and ethics (moral judgement of what is good or bad).

The first theories of heritage emerged by defining axes of value in this context imbued with Hegelian aesthetics and Neo-Kantian criticism. Indeed, Riegl’s seminal work

Der moderne Denkmalkultus (1903) [

25] was clearly an

axiological book, influenced by the theory of value judgement initiated by Hermann Lotze’s aesthetic philosophy [

26]. He does not discuss economic, aesthetic, or moral values, but rather “

Denkmalswerte”. Although his thinking was in line with other works of his time (Ruskin, Viollet-le-Duc, Boito, etc.), he was the first to formulate a coherent system of values. His essential contribution was to show that these values can be contradictory [

24]. Riegl was the first to make a clear distinction between “monument” (intentionally embodying history a priori with subjectivity) and “historical monument” (unintentionally embodying history a posteriori through our objective reading of it).

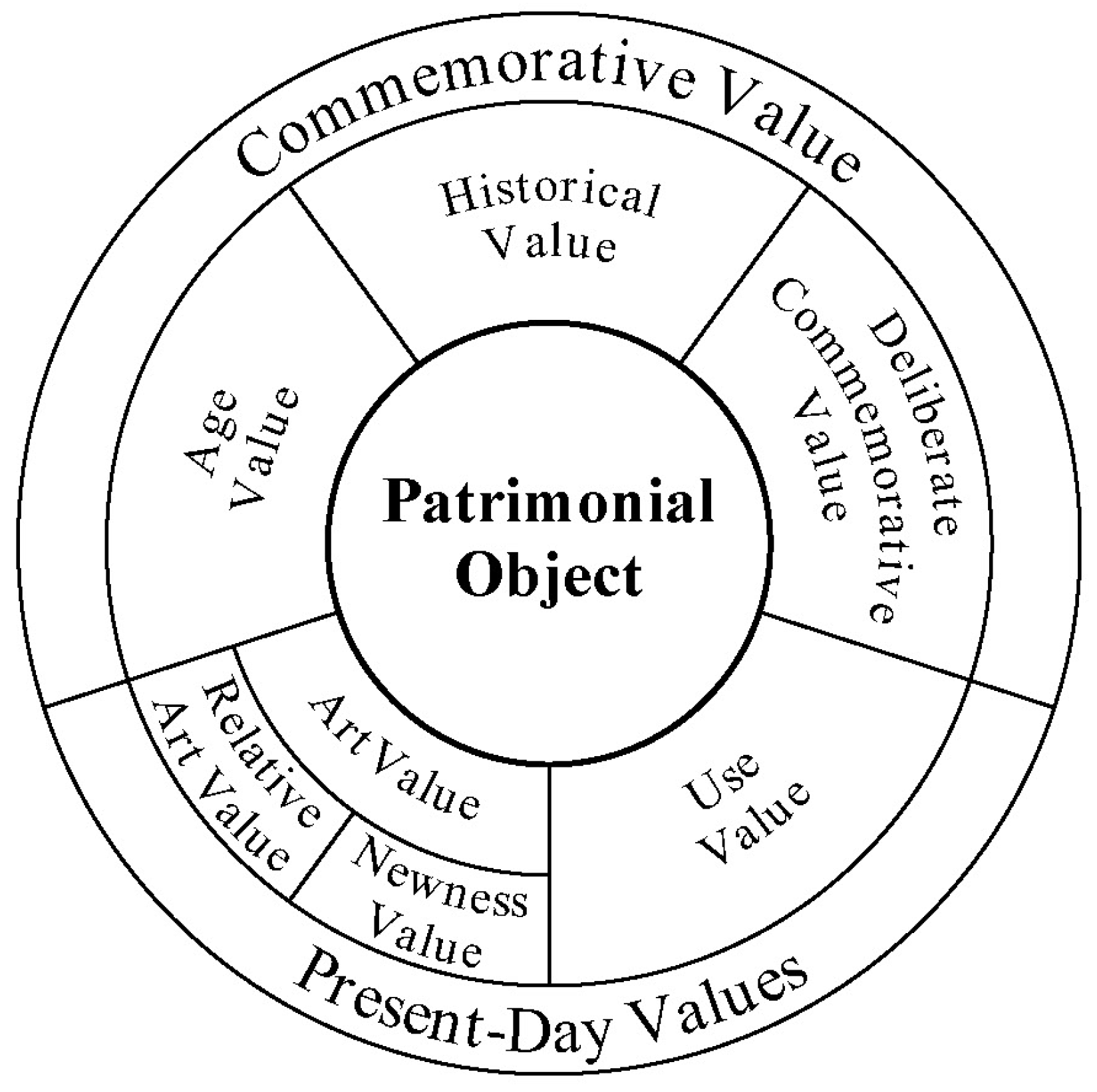

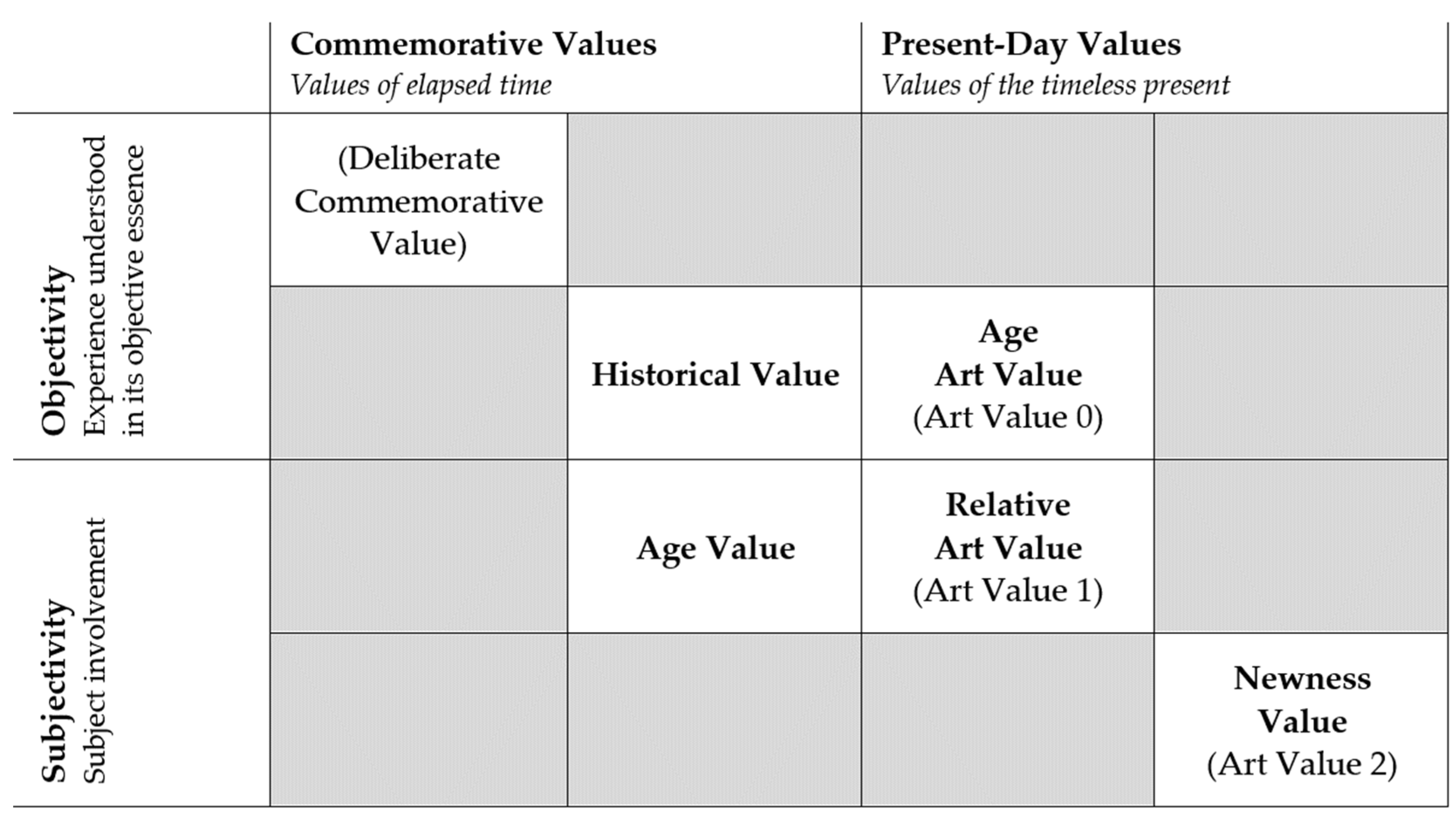

After making this distinction, Riegl [

25] defined two groups of values likely to confer importance on buildings (

Figure 2).

(1) On the one hand, the three “Commemorative Values” are linked to the past and involve memory:

“Age Value” refers to the age of the monument and the effects time and nature have had on it, and therefore, to the principle of accepted deterioration.

“Historical Value” concerns the original state of the work and justifies its conservation by interrupting any process of degradation.

“Deliberate Commemorative Value” generally arises from the fact that the monument was built in the first place, and prevents it, and above all what it represents, from sinking into the past.

(2) On the other hand, two “Present-Day Values” are linked to the experience of the present by their ability “to satisfy those sensory and intellectual desires of man” [

27] (p. 78). Present-day values see monuments as on “a par with a recently completed modern creation” having “the appearance of absolute completeness and integrity unaffected by the destructive forces of nature” [

27] (p. 98):

Although the various heritage values appear incompatible, both Boito and Riegl demonstrate that the apparent contradictions between certain values need to be considered in light of other factors—such as the condition of the monument and the social and cultural context in which it is situated—so that they can be the subject of compromise and nuance. Within this analytical typology, there are many bridges between the different values that make them up. Over time, the establishment of one value can lead to the emergence of another. The diversity of the proposed values clearly positions built heritage in the realm of cultural objects and therefore gives its transmission a meaning that goes beyond simple “Use Value” [

28]. The richness of this diversity allows Riegl’s theories to be put to practical use: “In his presentation, the notion of value plays a primarily practical role. The grid of values is an instrument for clarifying and bringing order to the clash of opinions” [

29].

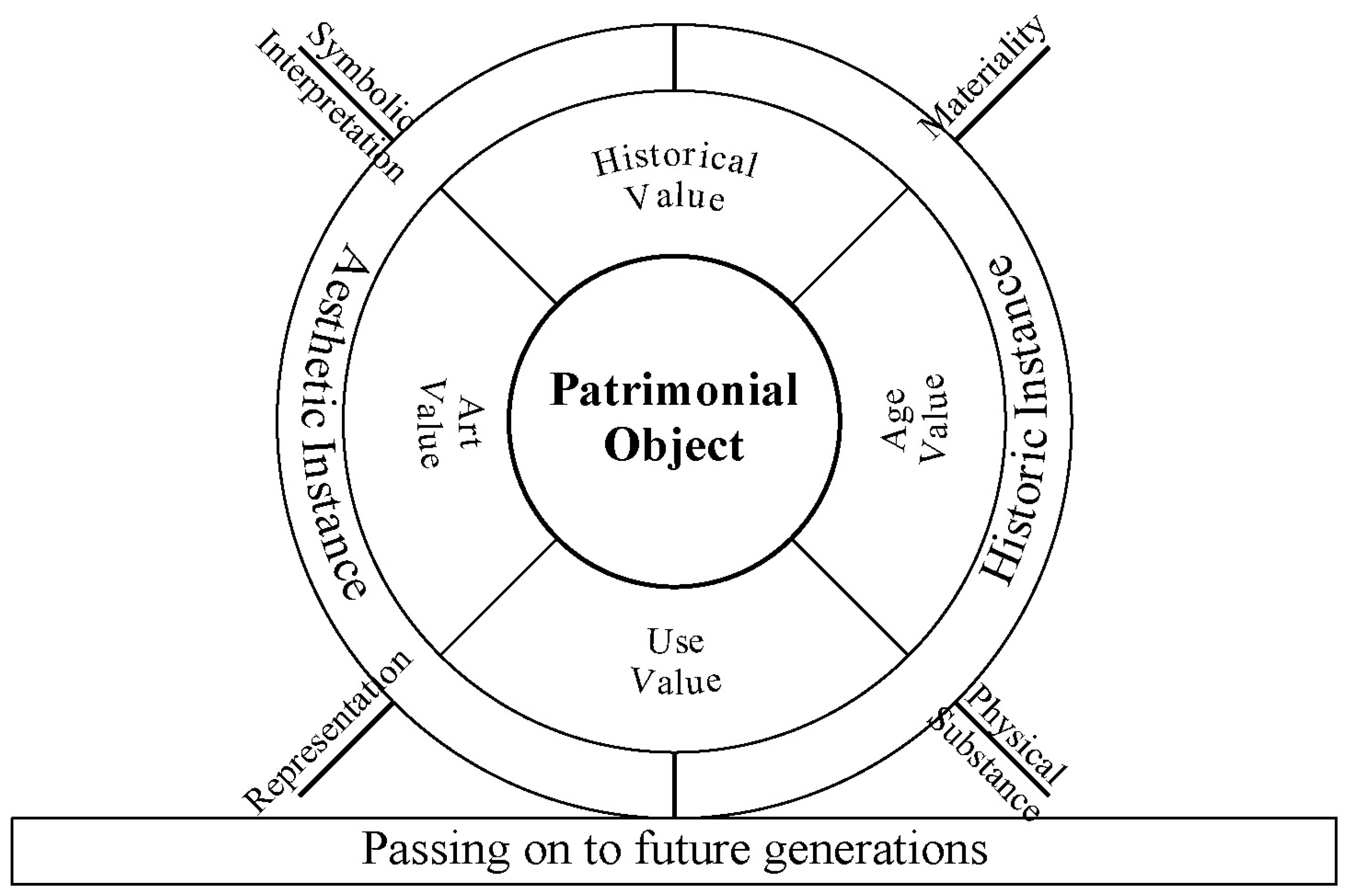

With its phenomenological approach in

Teoria del restauro, Brandi [

30] provides ideas complementary to Riegl’s concerning the restoration of works of art, which can be transposed to the restoration of built heritage, with a view to its transmission to future generations. Brandi first considers the work as a “

prodotto humano”, the object of a particular conscious (hence material) recognition. Then, demonstrating that the most important aspect to consider is, above all, the material consistency of the work through which the image manifests itself, he questions it from the points of view of two instances [

30] (p. 6):

The “aesthetic instance”, or the quality of the image’s transmission through which the work reveals itself, the existence of which is made possible by the material that supports it.

The “historic instance”, or the degree of alteration and transformation to which the material constituting the image has been subject during the life of the work.

If the assessor favours aesthetic instance, he will value the image more because it gives meaning, whereas if he favours historical instance, he will value the material more because of its archaeological dimension.

From this, Brandi draws his main definition of restoration: “the methodological moment in which the work of art is recognised, in its material form and in its historical and aesthetic duality, with a view to transmitting it to the future” [

31] (pp. 22–23).

Boito and Riegl’s contributions, combined with Brandi’s phenomenological approach (

Figure 3), demonstrate that the antagonisms Riegl sensed between the values of contemporaneity and recollection are blurred in Brandi in favour of polarisations between image and material, between symbolic interpretation and physical consistency, and between aesthetic and historical instances.

However, this polarisation focuses the evaluator on the object itself but tends to blur its social value, which considers its use and implies the cultural context of it.

4. Postmodern Condition and Interweaving Complex Thinking

Due to its semantic richness, the meaning of the word value remains difficult to determine. Classical axiology of the nineteenth century attempted to define several, but it was not until the twentieth century that the influence of the evaluator’s point of view and the evaluation process itself was clearly questioned.

In the same way that the modern science of the Enlightenment provided a context for the emergence of the classical axiologies of the nineteenth century, overcoming the Cartesian framework for observing reality provides a basis for the development of contemporary typologies of values. The paradigm shift from the Cartesian method to systems thinking has been described on several occasions and in different fields [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Holistic concepts do not replace analytical precepts but complement them by integrating the interdependence of observed phenomena, the uncertainty of processes, the subjectivity of observers, and the human and environmental sciences. Alongside the adaptation of the scientific paradigm, a societal rupture emerged around May 1968, traditionally illustrated by the shift from a modernist “machine for living” [

38], planned with an abstract, fixed, and disembodied aesthetic, to a postmodernist “genius loci” [

39], inhabited in tune with the sensory experience of inhabitants and the sociocultural fabric of the place.

The assessor is traditionally assumed to be rational in his choices and the evaluation process is assumed to be linear. But belief in absolute objectivity across all evaluative processes has been challenged on at least four counts [

40].

(1) Any evaluation is based on knowledge that is partially

constructed [

41] by the assessor. Knowledge is produced by the knowing subject based on their own interactions with reality and is therefore not an exact reflection of reality itself: “There is no absolute reality, but only subjective and often contradictory conceptions of reality” [

42] (p. 140). From this point of view, the quest for a

true understanding of the qualities of a heritage object is unsound.

(2) All value judgements are affected by cognitive biases produced by the necessary limitations of the human brain. The assessor does not have a rational and infallible way of thinking but suffers from “bounded rationality” [

43] (p. 196), which makes

full comprehension of the real world impossible. The assessor also reasons like a “statistician”, reconstructing a probable reality by balancing data from past experiences with perceptions [

44,

45]. These are all biases likely to affect the objective evaluation of heritage objects.

(3) Any evaluation process involves the subjective association of meaning with the objects observed. The assessor evaluates his positions (he self-assesses his decision-making) and his practices (he questions his actions) to give them meaning and check their conformity with values (a set of reference values constructed and acquired psychologically and socially). In the broadest sense, evaluation is the assessor’s relationship with value. This relationship both constructs and is constructed by the individual {Citation}, which makes it partly dependent on a process of personal referencing.

(4) All evaluation processes are influenced by the tools used: “We have to remember that what we observe is not nature in itself but nature exposed to our method of questioning.” [

46] (p. 58). When an assessor uses a method, a tool, or an evaluation grid, he must

integrate it, which requires psychological work; he must

adhere in one way or another to the heritage interpretation grid used, which inevitably influences subsequent choices.

The posture of sanctifying the object out of context, without considering the subjectivity of the evaluator valued in a Cartesian spirit [

19], is regularly juxtaposed with the English posture of the object in its daily use [

16]. Similarly, Cartesian analysis was based on the knowledge of the object, while the systemic approach focuses on the object’s relationships with its context, leading to the following consequences: (1) a shift from object value to social value (from built heritage to user, social, and tourist heritage), incorporating questions of who the heritage is intended for and who evaluates it; (2) a transition from top-down axiological models to bottom-up charters, developed through long collaborative processes of discussion and argumentation (postmodern attitude).

In this spirit, the work of ICOMOS is remarkable. The

Nara Document declares that “it is of the highest importance and urgency that, within each culture, recognition be accorded to the specific nature of its heritage values and the credibility and truthfulness of related information sources” [

47]. The primacy of European and Anglo-Saxon values is relativised, while regional particularities are revalued. Consequently, heritage assessment integrates an expanded contextual analysis including, according to the

Xi’an Charter [

48], “interaction with the natural environment; past or present social or spiritual practices, customs, traditional knowledge, use, activities and other forms of intangible cultural heritage aspects that created and form the space as well as the current and dynamic cultural, social and economic context”. From the

Quebec Charter [

49] onwards, heritage becomes an “innovative and efficient manner” for “sustainable and social development”. This position is confirmed in the

Paris Declaration [

50], stating that the “ownership of heritage strengthens the social fabric and enhances social well-being”, and in the

Principles of Valetta [

51], advocating for “a greater awareness of the issue of historic heritage on a regional scale […] of traditional land use, the role of public space in communal interactions, and of other socioeconomic factors such as integration and environmental factors”. Finally, in the preliminary debates for the

Florence Charter [

52], it is suggested “that evaluating and assessing a site as World Heritage should be considered as an ethical commitment to safeguarding and respecting human ‘values’ in order to protect the spirit of place and people’s identity so as to improve their quality of life”.

The importance placed on human values in relation to their context crystallises in the project for the

Intangible Cultural Heritage Charter led by ICOMOS and ICICH [

53], which establishes that “processes of development, whether they be to the benefit or detriment of community well-being, may also impact heritage spaces/sites associated with intangible cultural heritage. The intangible cultural heritage associated with a place is not necessarily evident to those propagating development, especially if they are not part of a community that is associated with such sites”.

The bottom-up approach of these frameworks demonstrates an increasing consideration of social values arising from the inseparability of intangible and tangible heritages, upon which the sense and relevance of their evaluation rest.

5. From Complexity to Typologies of Values

The philosophical background behind the introduction of the idea of

value in restoration theory has been criticised [

54], and the possibility of obtaining total objectivity in any evaluation process has been called into question on scientific grounds. Nevertheless, theoretical models of heritage assessment in the twenty-first century retain the ambition of proposing objectivity tools. Thus, as Russell and Winkworth [

55] (p. 13) state, “while there will always be an element of personal judgement and enthusiasm in the statement of significance, using a consistent process and criteria ensures that assessments are rigorous and well substantiated. At their best, statements of significance combine logic, passion and insight”.

In this context, a genuine ecosystem of theoretical models for heritage evaluation is being established.

After creating a non-exhaustive list of different “value typologies” used in the “conservation-restoration” of “cultural property”, Lemaitre [

56] compares the types of internal relationships between values. From there, he distinguishes three different internal structures of typologies of values, which are reinterpreted here as follows:

The

lists of unrelated values in which, for example, Mason [

57] groups sociocultural values and economic values together in two different evaluation modes; Appelbaum [

58] proposes dynamic values, incorporating the temporality of the object during which values are likely to change.

The

opposition of sets of values in which the object is evaluated in relation to each value in the typology: aesthetic instance and historical instance [

30]; values of remembrance and values of contemporaneity [

25]; the intentional values of the artist and the attentional values of the audience [

24]; and cultural–historical values of the past and contemporary socioeconomic values [

59].

The

integrated core values approach is determined by multiple approaches to evaluation criteria. The object is studied in relation to all these values, although not all of them are relevant to its evaluation. The evaluation involves assigning the principal values the object must meet, and the other sets of criteria are used to define the principal values. Russell and Winkworth [

55], for example, classify four primary values and comparison criteria in their model; Versloot [

60] builds a typology around three main values and groups formal characteristics separately.

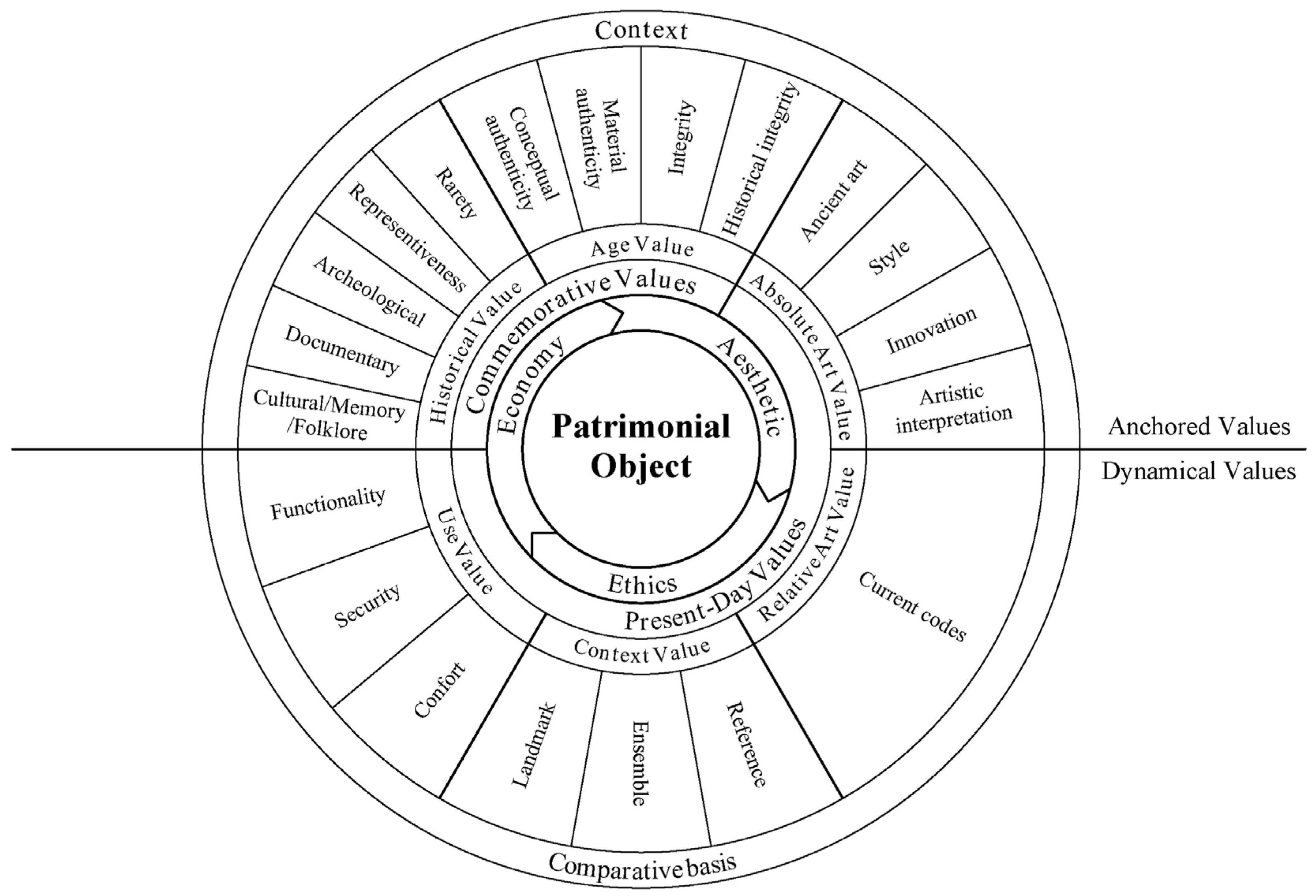

Based on their previous research aimed at developing better support for the heritage evaluation of residential buildings in Brussels [

61], Bos and Stiernon therefore continue by proposing a new interpretation of values based on a critical review of the state of the art. Their proposal, identified as an integrated approach, seeks to establish, at a given moment, a synthesis between values objectified by knowledge (anchored) and values related to experience and objectifiable by consensus (dynamic).

The typology of values and the evaluation method framing it are based on the values initially stated by Riegl, adapting and supplementing them with sub-values. Some of these sub-values are already used in the monument classification procedures by the three Belgian regional institutions, highlighting their primarily practical nature. Other sub-values have been identified based on current concerns, as found in the literature and through expert consultations.

Given the

practical objective of this typology (

Figure 4), the use of a priori

objectified (sub-)values is favoured, without excluding a posteriori

objectifiable (sub-)values.

This polarisation of values based on their level of objectivity is central to Davallon’s theory [

62]. Indeed, by reinterpreting Riegl’s axiology, he repositioned the values of remembrance and the values of contemporaneity according to the criteria of objectivity and subjectivity (

Figure 5) with the aim of attributing, or not,

value to a monument. Furthermore, he distinguishes, on one hand, values linked to external criteria related to the conception of the object by its author, accessed through the object itself, and on the other hand, values defined based on criteria related to contemporary subjects: the “receivers”. The former is then considered objective, while the latter is linked to the subjective perception of the evaluators.

Although his method is interesting, the culture of antagonism that ensues is questionable. Bos and Stiernon therefore attempt to transcend this polarity by systematising all evaluations through a series of specific questions requiring reasoned responses, thereby moving beyond the checklist principle and allowing values to be objectified through argumentation.

Through his approach, Davallon also highlights the role played by societal transformation in the attribution of values and the dynamic nature it implies. The difficulty in objectifying the values associated with a heritage object primarily lies in the interpretation of its so-called cultural dimensions.

In their own synthesis, Fredheim and Khalaf [

63] also challenge static value typologies. Given the subjective and changing nature of values, they believe that each heritage evaluation is embedded in a context and a time. Value typologies must therefore consider the values an object had in the past, those it has in the present, and the potential value it could have in the future. Furthermore, they conclude that the typologies of values found in the literature do not consider the dynamic and contextual characteristics of the evaluation processes of which they are a part.

To address these shortcomings, Bos and Stiernon emphasise the need to examine each value and sub-value in relation to its geographical, historical, physical, and especially societal context. Evaluation on the basis of common elements observed makes the formation of a comparative base essential to a truly integrated approach (object from the same period, style, author, function, typology, construction system, or similar context or territory).

While, as Davallon argued, some values are “anchored” as they are intrinsically linked to the object’s conception and the historical context in which it was erected, it seems essential to incorporate parameters, comparison tools, and integration methods into the evaluation process that allow for nuanced contemporary reception of the object and thus an understanding of its heritage value at any given moment. Moreover, the typology as presented allows for a form of evolution that ensures the integration of newly encouraged values by charters such as social values or other intangible values.

This proposal is therefore not intended to be an end in itself but rather a tool that is adaptable according to the heritage object, the era, and the evolution of societal concerns.

6. Conclusions of the Literature Review on Value Typologies

Before taking any action concerning an object, the actors involved engage in an evaluation process to objectively identify heritage values, on which basis they consider possible intervention strategies. But the variety of the values identified, the processes used, and the objectification methods employed raise questions.

Throughout history, the assessment of building heritage has primarily focused on aspects such as its physical and material qualities, its future, its monetary value and its moral significance. Over time, this process has evolved alongside shifts in intellectual and scientific paradigms, highlighting two significant historical periods, which have influenced how heritage objects are evaluated.

In the wake of Cartesianism, which broke with religious beliefs, modern science developed based on a rationalist stance and the analytic method. In architecture, the constructive, material, and economic conditions under which buildings are constructed are evolving, at once dethroning and sacralising monuments. By tracing the use of the word value and its derivatives in economic, aesthetic, and ethical discourse, we can see that philosophical axiology provided a context for the emergence of heritage axiologies in the nineteenth century;

Modern science was viewed in a positive light for three centuries before its foundations were called into question in the twentieth century by complex thinking. This systemic approach to modelling assumes the interdependence of the phenomena studied while remaining rational. At the same time, the heritage axiologies of the twentieth century were adapted to new dynamic typologies of values in the twenty-first century, incorporating the dynamic evolution of values, their definitions and their relationships, the subjectivity of evaluators, and the circularity of evaluation processes.

These two periods correspond to two “interpretation” approaches to heritage assessment [

64]: from value typologies defined by expert knowledge (“positivism”) to a growing recognition of the interpreter’s role, including users and visitors of heritage sites (“constructivism”), so that the “process of understanding” the value of a heritage object is like a “socio-cognitive process”, “greatly influenced and determined by culture, or rather through the collective knowledge systems embedded in it” [

65] (p. 120).

Nowadays, with increasing and indisputable importance, several contemporary issues alter the choice, definition, and tensions among values within typologies: (1) the dynamic challenges of

sustainable development make it necessary for heritage to make a contribution, mainly by emphasising the adaptability of its use value, its material value, and its social values, but these choices can be made to the detriment of its cultural and symbolic values [

66,

67]; (2) paradoxically, the

digitisation of reality seems to minimise the importance of use or material in favour of that of the image [

68], while at the same time providing high-precision survey tools, collaborative BIM models, and the possibility of creating true “digital twins” in the form of dynamic digital archives [

69]. Other contemporary issues also call into question traditional heritage values: urban growth, economic crises, changing lifestyles, new technologies, etc.

Numerous evaluation grids have therefore attempted to define value systems with varying degrees of relevance. Given the facts, it seems illusory to propose an additional, supposedly definitive value grid that all heritage stakeholders will have to use to decide, with certainty, what actions to take concerning the built environment with a view to passing it on to future generations. At this stage, a form of excessive relativism would appear to definitively discredit any attempt to define heritage values. But this would be forgetting that complex thinking does not replace the analytical method; rather, it complements it: rational models that incorporate the subjectivity of evaluation enable the development of reasoning that objectifies knowledge.

7. Discussion: Objectivising with a Value Grid

The hypothesis supported here is that the

heritage value grid constitutes an operational scientific tool leading to a reasoned approach to the object to be evaluated. The “typology of values” [

56] is a “methodological tool” for “evaluating a cultural asset”, a form of “theoretical model” for “organising cultural values among themselves” and, on that basis, “defining

the value of a cultural asset”. Although they are “rarely challenged by those who use them”, typologies have the advantage of “underpinning conservation-restoration treatment choices”. Bearing in mind its obvious limitations, the value typology therefore remains the most effective practical analysis tool for organising a system of predefined values and getting them to interact during an assessment process: “The value grid is an instrument for clarifying and bringing order to the clash of opinions” [

29].

From this, a definition is possible: a heritage value grid is a dynamic system of values, defined prior to the assessment process, whose purpose is the practical and rigorous assessment of a heritage object. It is used before deciding what action to take (or not) to fulfil the potential of an evolving object. The grid could be considered as a compass of heritage values or a gyroscope enabling the assessor to keep track. It attempts to balance the subjectivity inherent in the general question of evaluation with the objectivity sought when evaluating an object.

Using the state of the art established above, the cross-fertilisation among authors has led to some thoughts and points worth considering.

The use of the comparative method is essential to objectify the evaluation process. It consists of considering the object within a wider corpus of other objects to detect its distinctiveness, specific features, or representativeness. This method involves drawing parallels between different study objects, either partially or entirely, by analysing similarities and differences. The process includes (1) defining the subject of study (heritage object to be compared); (2) establishing a corpus of objects for comparison based on the study topic; (3) identifying criteria (the elements of the object that can be compared with others); (4) clearly stating indicators (to measure criteria); (5) gathering relevant information for criteria in all the corpus; and (6) contrasting the collected data and formulating conclusions.

With a comparative method, the use of a predefined shared criteria-based grid of values provides assessors with a structured framework, making it easier to establish consensus-based values, criteria, and indicators. Otherwise, adherence to shared cultural references and the construction of a foundation of common values are necessary for any conversation between actors and the transmission of meaning to future generations. The collegiate nature of the evaluation leads assessors to interact to reach a consensus, which reinforces the objectivity of the process.

Once a value grid has been chosen, the

value weighting is challenging for the assessor. It is complex to objectivise the

weight allocated to each value of a heritage object or to objectivise the comparison between the

weights assigned to many objects. The assessment grid distinguishes between values, and the importance of each value can be weighted by the assessor according to indicators. Of course, the assessor partially actively constructs their “own understandings” of the world in which they live [

64] (p. 84), but the grid and the indicators predefined by themself, another assessor with more expertise, or pre-set in conversation with others assessors, allows the assessment to be recontextualised in terms of a broader heritage culture.

On the one hand, each heritage object is multifaceted. A priori, every object can be evaluated at least regarding all the values of the typology. But on the other hand, the construction of an

open value typology makes it possible to integrate

new (sub-)values aligned with the evolving contemporary aspirations (such as social value or another intangible dimension). The opportunity to adjust the grid challenges what Smith [

70] (pp. 29–34) calls the “authorized heritage discourse” (AHD), an example of Western-centric perceptions of “heritage”, which ironically “assume the tangible is somehow ‘dead’ and paradoxically ‘preservable’” (p. 274). Indeed, the heritage “discourse” is rather a “social practice”, a dynamical and open-ended cultural process, linking “social meanings, forms of knowledge and expertise, power relations and ideologies” (p. 4).

Provided that a “constructivist approach” is adopted [

64], assessors gain

experience over the course of past evaluation processes, enabling them to gradually develop the knowledge (degree of rarity, originality, representativeness, etc.) by which they identify, combine, and weight values, as well as define criteria and give measure with indicators.

8. Conclusions: A Constructivist Approach of Value Grid Heritage Assessment

The concepts of value, evaluator, typology of values, and heritage assessment are examined together here from the perspective of a dynamic process of heritage evaluation. From this point of view, combining a constructivist approach with the use of a criteria-based value grid allows the process to remain sufficiently

open to avoid the pressure of the “authorized heritage discourse” (AHD) [

70], while keeping the assessment process as objective as possible at a given time.

Based on a reinterpretation of the subject–object dialectic [

71], an evaluator is considered a learner (subject), constructing their knowledge about a heritage object (object), by integrating lived experiences (perception) and their representations (reasoning). This process shapes an evolving mental representation, forming a structured “schema” that adapts to their thoughts. During the evaluation process, they integrate new information through “assimilation”, reinforcing existing knowledge, or through “accommodation”, modifying their “schema”. This continuous “equilibration” process allows the evaluator to progressively refine their categorisation of the evaluated object, enabling them to make the most objective decision-making possible within the limits of their knowledge.

The evaluator’s degree of subjectivity remains constant, but specific issues may lead them to prioritise certain values over others. Indeed, when new information is particularly striking (such as in crisis situations), gains significant conversational space (through extensive media coverage), or challenges existing beliefs (raising ethical concerns), the evaluator may reconsider pre-established evaluation.

When an evaluator uses a predefined value grid as an instrument to aid in assessment, it introduces an additional mediation in the subject–object dialectic. Each heritage evaluation grid partially adapts its predecessors based on the evolution of knowledge and social issues. From one grid to another, the organisation of values evolves (identification, distinction, hierarchy, and interaction), and evaluation methods become more precise (comparative analysis, radar diagrams, statistical approaches, etc.). Through its continuities and discontinuities, the succession of grids, by enabling various forms of mediation, indirectly generates a genuine dynamic of objectivisation in heritage assessment. In other words, what was evaluated in the past can be reassessed differently today and may be re-evaluated again in the future. And while the evaluation grid may adapt, the quest for objectivity remains constant.