Al-Madafah in Sweida, Southern Syria: An Exploration of Architectural Heritage and Socio-Cultural Significance

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Hospitality ‘Al-Diyafah’

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Physical and Spatial Characteristics of Madafahs

3.2. Historical Evolution

3.2.1. Al-Madafah in the Feudal Era 1838–1888 AD

3.2.2. Al-Madafah After the Popular Movement (Peasants’ Revolution) 1889–1890 AD

3.2.3. Al-Madafah in the Face of Occupation

3.3. Socio-Cultural Role of Madafahs

3.3.1. Al-Madafah as an Educational Institution

3.3.2. Al-Madafah as a Place to Foster Cultural Identity and Artistic Expression

3.3.3. Al-Madafah as a Court for Solving Community Problems

3.4. Contemporary Role of Al-Madafah

3.5. Case Studies

3.5.1. Al-Madafah as a Museum ‘Abo Samer Madafah’

3.5.2. AL Jarmaqani Madafah ‘If a Door Could Speak’

3.5.3. Jazzan Madafah, Ijtimaa Qanawat: A Testimony of Forgiveness

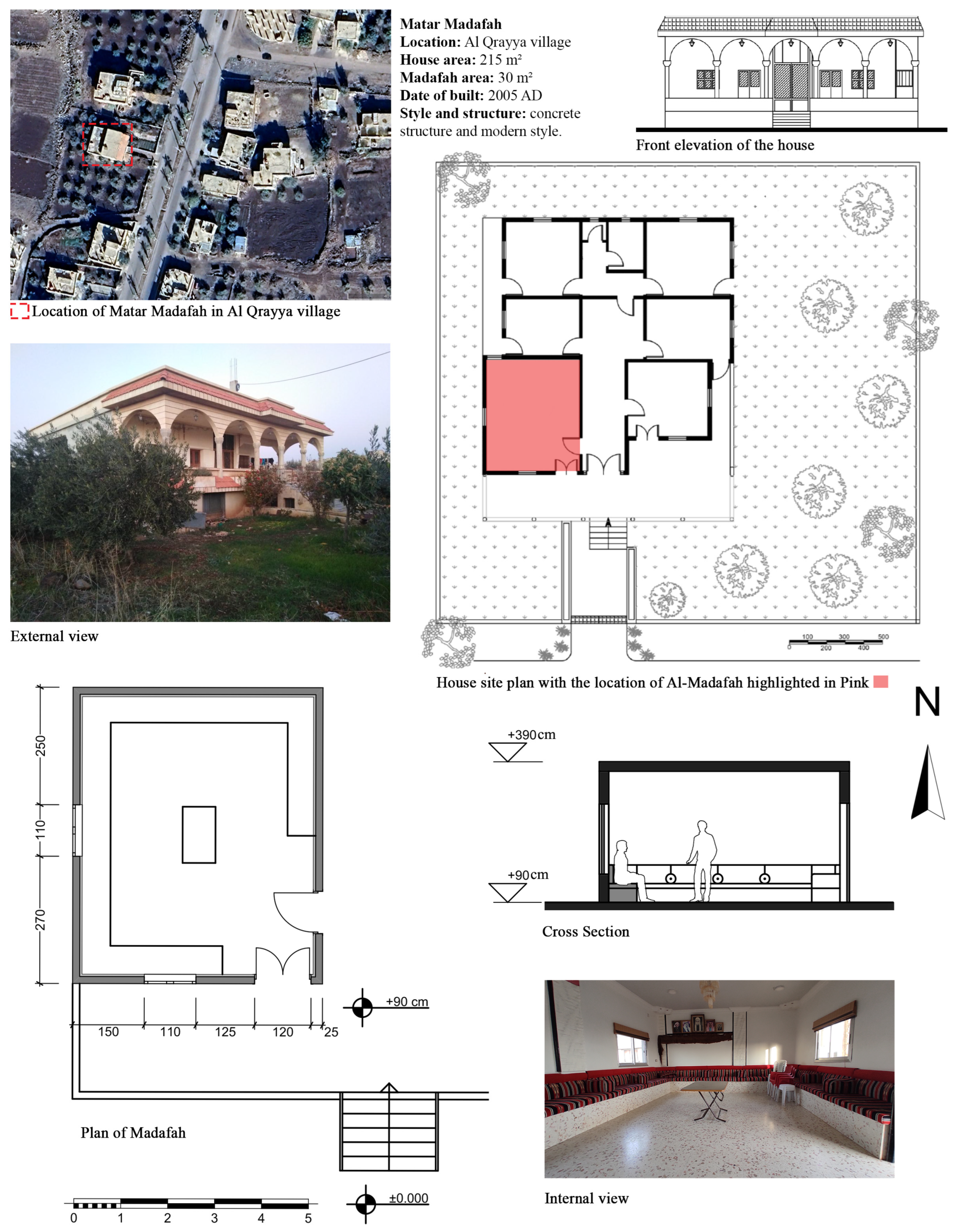

3.6. Morphologies and Living Legacies

3.6.1. Hneidy Madafah in Al-Majdal, ‘A Symbol of Resistance’

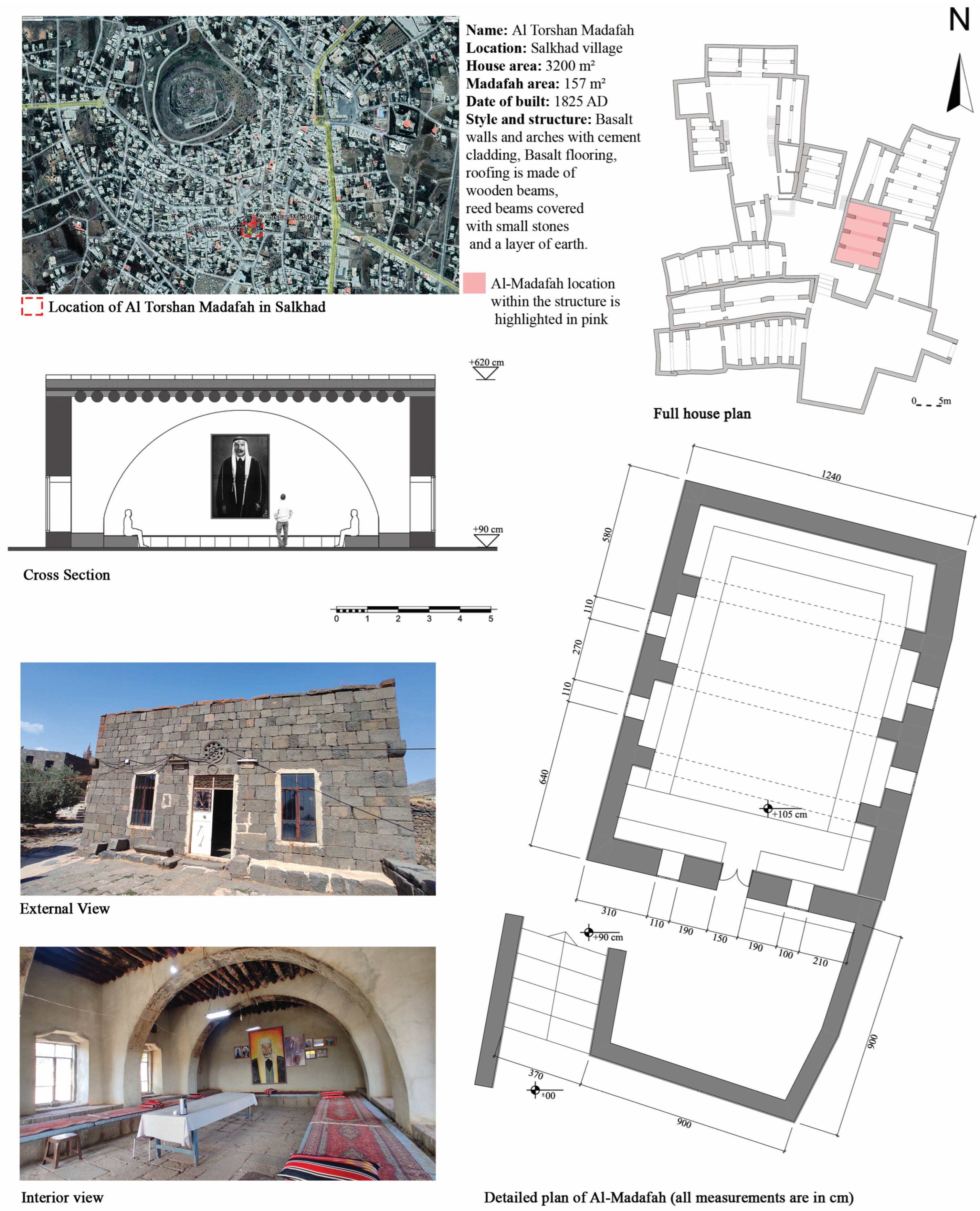

3.6.2. Al-Torshan Madafah in Salkhad: ‘From Father to Son: Inheriting Hospitality’

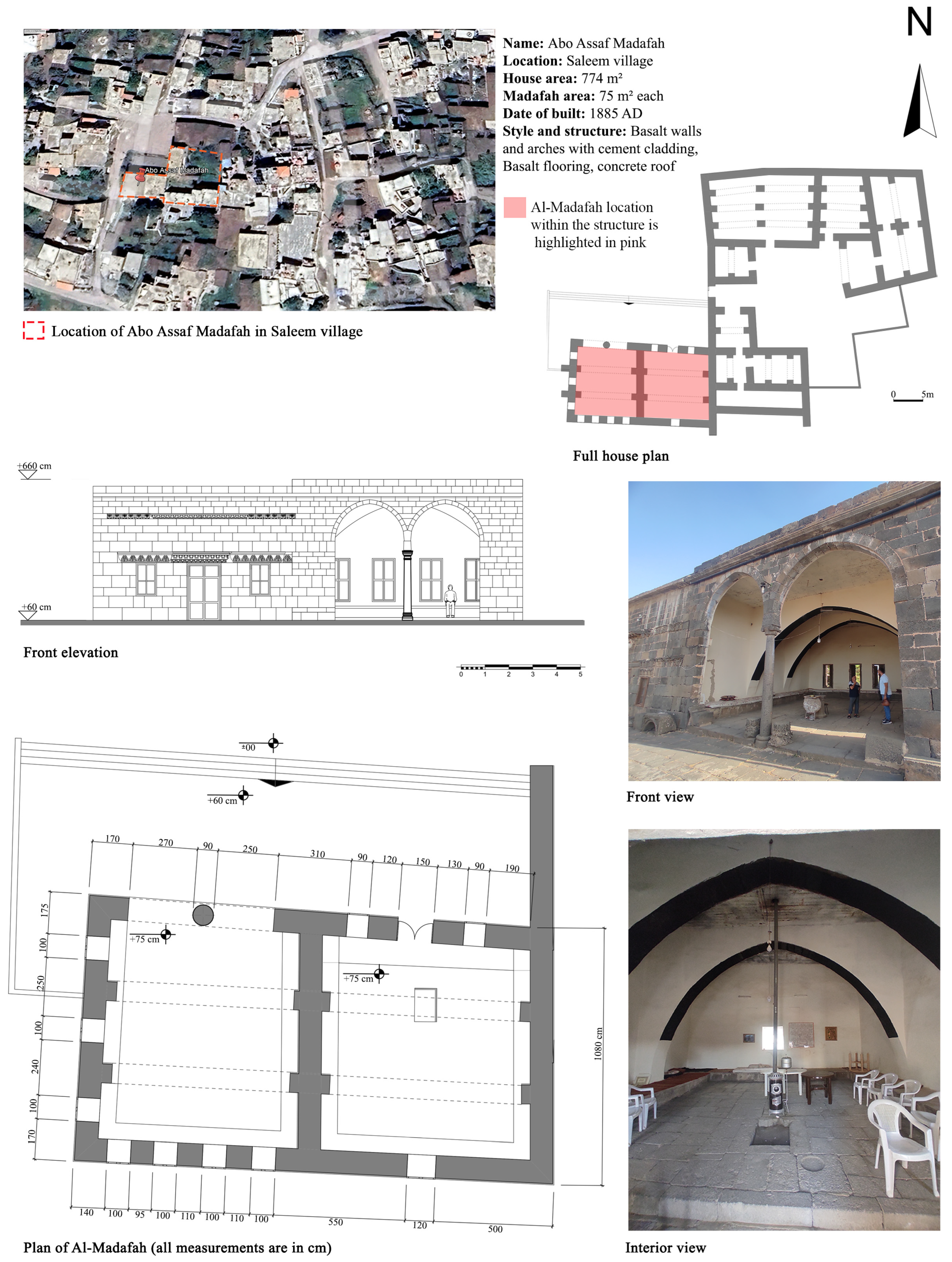

3.6.3. Abo Assaf Madafah: A Century of Social and National Initiatives

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Code | Age | Education | Gender | Role | Location | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mo1 | 76 | Primary school | M | Farmer | Taraba | 12 August 2023 |

| Mo2 | 68 | Primary school | M | Farmer | Orman | 22 October 2023 |

| Mo3 | 79 | Primary school | M | Farmer | Qanawat | 10 October 2023 |

| Mo4 | 63 | High school | M | Farmer | Al Majdal | 7 September 2023 |

| Mo5 | 51 | Primary school | M | Farmer | Salkhad | 20 October 2023 |

| Mo6 | 55 | University degree | M | Teacher and researcher | Saleem | 10 November 2023 |

| Mo7 | 59 | High school | M | Farmer | Al-Qrayya | 7 December 2023 |

| Ex1 | 52 | University degree | M | Local tourist guide | Sweida | 5 August 2023 |

| Ex2 | 43 | Master’s degree | M | Heritage professional | Qanawat | 10 October 2023 |

| Ex3 | 65 | Higher education | F | Historian & Researcher | Sweida | 12 December 2023 |

| Ex4 | 49 | Master’s degree | F | Architect | Sweida | 8 October 2023 |

| Cm1 | 39 | High school | M | Local community member | Al-Majdal | 7 September 2023 |

| Cm2 | 52 | University degree | M | Local community member | Orman | 22 October 2023 |

References

- Zare, M.H.; Kazemian, F. Reviewing the Role of Culture on the Formation of Vernacular Architecture. Eur. Online J. Nat. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 547–553. [Google Scholar]

- Abo al-Hasan, S. Al-Madafah in Jabal al-Arab (المضافة في جبل العرب) Translated from Arabic; Folklore “Al-Turath al-Shaabi”: Baghdad, Iraq, 1975; Volume 11, pp. 55–75. Available online: https://archive.alsharekh.org/Articles/263/22672/513151 (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Provence, M. The Great Syrian Revolt and the Rise of Arab Nationalism; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2005; Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7560/706354 (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Hazran, Y.; Reed, M.A.; Schäbler, B.; Timani, H.S.; Zeedan, R. The Status of Druze Studies and Launching the Druze Studies Journal (DSJ). Druz. Stud. J. 2024, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshboul, A.M.; Shboul, N.M.H.; Dalou, A.Y.A.; Alrousan, M.; Alibeli, M.A. Al-Madafa and Ad-Diwan among Al-Shboul Tribe: A Case Study in Ash-Shajarah Village of Jordan. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 210–225. [Google Scholar]

- Maffi, I. The madāfa in Jordan, a place of memory. Etud. Rural. 2009, 184, 203–216. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zamil, F.A. The Interior Design of the Contemporary Diwaniya in Kuwait: Its Changing Social Role and Physical Form. Int. J. Architecton. Spat. Environ. Des. 2022, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chay, C. The Dīwāniyya Tradition in Modern Kuwait: An Interlinked Space and Practice. J. Arab. Stud. 2016, 6, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababsa, M. The madâfa in Raqqa: Transformation of a place of sociability tribal as an attribute of urban notability. Geogr. Cult. 2001, 37, 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, P.S. Introduction. In Syria and the French Mandate: The Politics of Arab Nationalism, 1920–1945; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1987; pp. 1–722. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7zvwbs.1 (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Betts, R.B. The Druze; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1988; Available online: https://archive.org/details/druze0000bett/page/n7/mode/2up (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Brown, R.M.; St, W. The Druze Experience at Umm al-Jimål: Remarks on the History and Archaeology of the Early 20th Century Settlement. 1988. Available online: https://publication.doa.gov.jo/uploads/publications/25/SHAJ_10-377-390.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Butler, H.C. Ancient Architecture in Syria: Section A, Southern Syria, Part 6 (Seeia). Leyden: Brill. (1915). Available online: https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.17018 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Abo Alhasan, S. سويداء سورية موسوعة شاملة عن جبل العرب (Sweida Syria—A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Jabal Al Arab); Alaa Eddine: Damascus, Syria, 1995; Available online: https://www.noor-book.com/en/ebook-2742-سويداء-سوريه-موسوعه-شامله-عن-جبل-العرب-2493-pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022). (In Arabic)

- Breamer, F.; Dentzer, J.-M.; Almaqdisi, M. Hauran v la Syrie du sud du Néolithique à L’antiquité Tardive Recherches Récentes Volume I; Presses de l’Ifpo: Beyrouth, Liban, 2010; Available online: https://books.google.co.in/books/about/Hauran_V.html?id=SuHO_uhZlisC&redir_esc=y (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Abou-Assaf, A. Ali Abou Assaf The Archaeology of Jebel Hauran, the Mohafaza of Souweida; Sidawi Printing House: Damascus, Syria, 1997; Available online: https://archive.apan.gr/en/data/accompanying-item/14572 (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Wahab, M. Features of traditional architecture in Jabal Al-arab, Southern Syria الخصائص المحلية للعمارة القديمة في جبل العرب. In Hawliyat athariya in the Syrian Arab Republic, Damascus, Syria; Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM): Damascus, Syria, 1990; pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Firro, K.M. A History of the Druzes; E.J. Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.H.; Aslam Akbar, M.; Abd Aziz, H. The personification of hospitality (ḍiyāfah) in community development and its influence on social solidarity (takāful ijtimāʿī) through the prophetic tradition (sunnah). J. Int. Inst. Islam. Thought Civiliz. 2021, 26, 1. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/77761485/The_Personification_of_Hospitality_Diyafah_in_Community_Development_and_Its_Influence_on_Social_Solidarity_Takaful_IjtimaI_Through_the_Prophetic_Tradition_Sunnah_?source=swp_share (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Timani, H.S. The Druze. In Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion; Brill Academic Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 724–742. Available online: https://brill.com/display/book/9789004435544/BP000045.xml (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Mousourakis, A.; Arakadaki, M.; Kotsopoulos, S.; Sinamidis, I.; Mikrou, T.; Frangedaki, E.; Lagaros, N.D. Earthen architecture in greece: Traditional techniques and revaluation. Heritage 2020, 3, 1237–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, P.S. Divided Loyalties? Syria and the question of Palestine, 1919–1939. Middle East Stud. 1985, 21, 324–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaebler, B. The Syrian Land: Processes of Integration and Fragmentation: Bilād al-Shām from the 18th to the 20th Century; Franz Steiner Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 1998; Available online: https://books.google.com.hk/books?id=B-iDgNPVuhAC (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Alshoufi, A. The Sheikh Al-Hajri Guesthouse Is a Destination for Politicians of Suwayda. 2023. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.net/politics/2023/10/2/ (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Vellinga, M. Engaging the future: Vernacular architecture studies in the twenty-first century. In Vernacular Architecture in the 21st Century: Theory, Education and Practice; Asquith, L., Vellinga, M., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2006; pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimbaysalami, O.; Ren, X. Heritage in Transition: Vernacular Architectural Patterns in Rural Iran. Heritage 2024, 7, 3393–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez-Castañón, D.; Cunha Ferreira, T. Toward the Adaptive Reuse of Vernacular Architecture: Practices from the School of Porto. Heritage 2024, 7, 1826–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.; Obeidat, B.; Gharaibeh, I. The impact of socio-cultural factors on the transformation of house layout: A case of public housing—Zebdeh-Farkouh, in Jordan. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asquith, L.; Vellinga, M. (Eds.) Vernacular Architecture in the 21st Century: Theory, Education and Practice, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alarbeed, B.Y.; Lakra, H.S.; Aryal, K.R.; Chettri, N. Al-Madafah in Sweida, Southern Syria: An Exploration of Architectural Heritage and Socio-Cultural Significance. Heritage 2025, 8, 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110487

Alarbeed BY, Lakra HS, Aryal KR, Chettri N. Al-Madafah in Sweida, Southern Syria: An Exploration of Architectural Heritage and Socio-Cultural Significance. Heritage. 2025; 8(11):487. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110487

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlarbeed, Bushra Yaroub, Harshit Sosan Lakra, Komal Raj Aryal, and Nimesh Chettri. 2025. "Al-Madafah in Sweida, Southern Syria: An Exploration of Architectural Heritage and Socio-Cultural Significance" Heritage 8, no. 11: 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110487

APA StyleAlarbeed, B. Y., Lakra, H. S., Aryal, K. R., & Chettri, N. (2025). Al-Madafah in Sweida, Southern Syria: An Exploration of Architectural Heritage and Socio-Cultural Significance. Heritage, 8(11), 487. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110487