The Lost Golden Room Courtyard Gallery in the Alhambra: Sources, Graphic Analysis and Digital Reconstruction

Abstract

1. Introduction

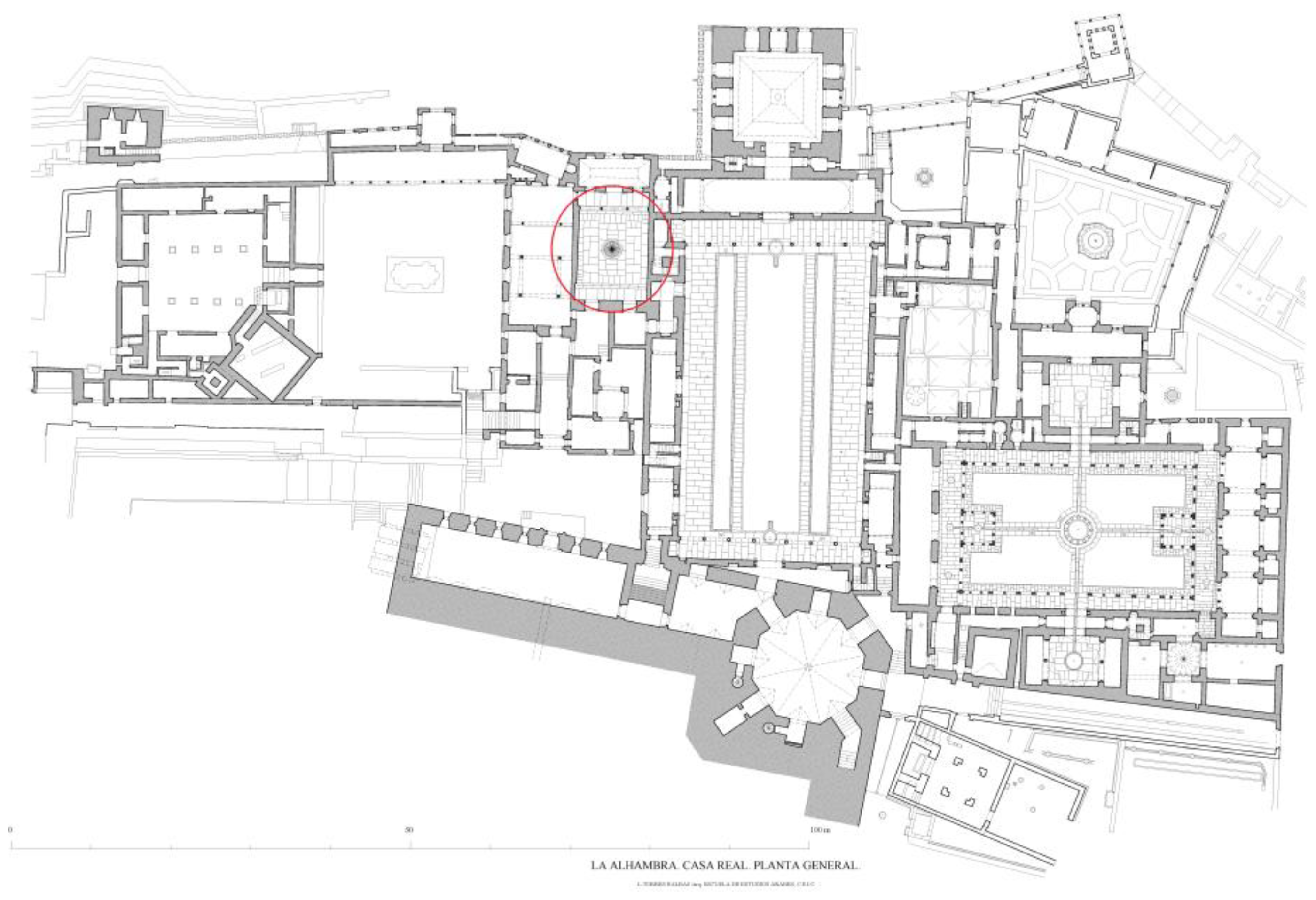

1.1. Brief Historical and Architectural Data

1.1.1. The Nasrid Alhambra and the Mexuar

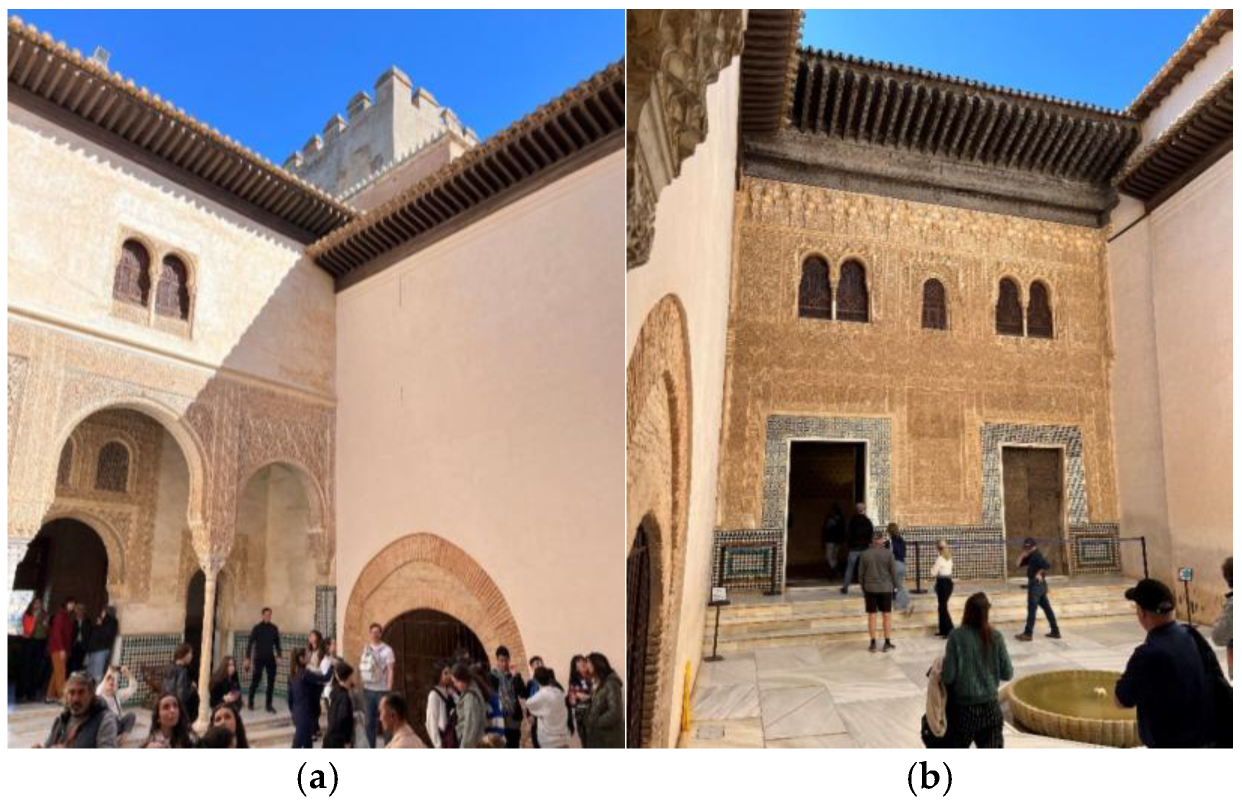

1.1.2. The Alhambra and the Courtyard of the Golden Room Transformed by the Catholic Monarchs

1.2. Previous Reference Research

1.2.1. Documents on the Works of the Catholic Monarchs in the Alhambra

1.2.2. The Conservation of the Patio Del Cuarto Dorado in the 19th and 20th Centuries

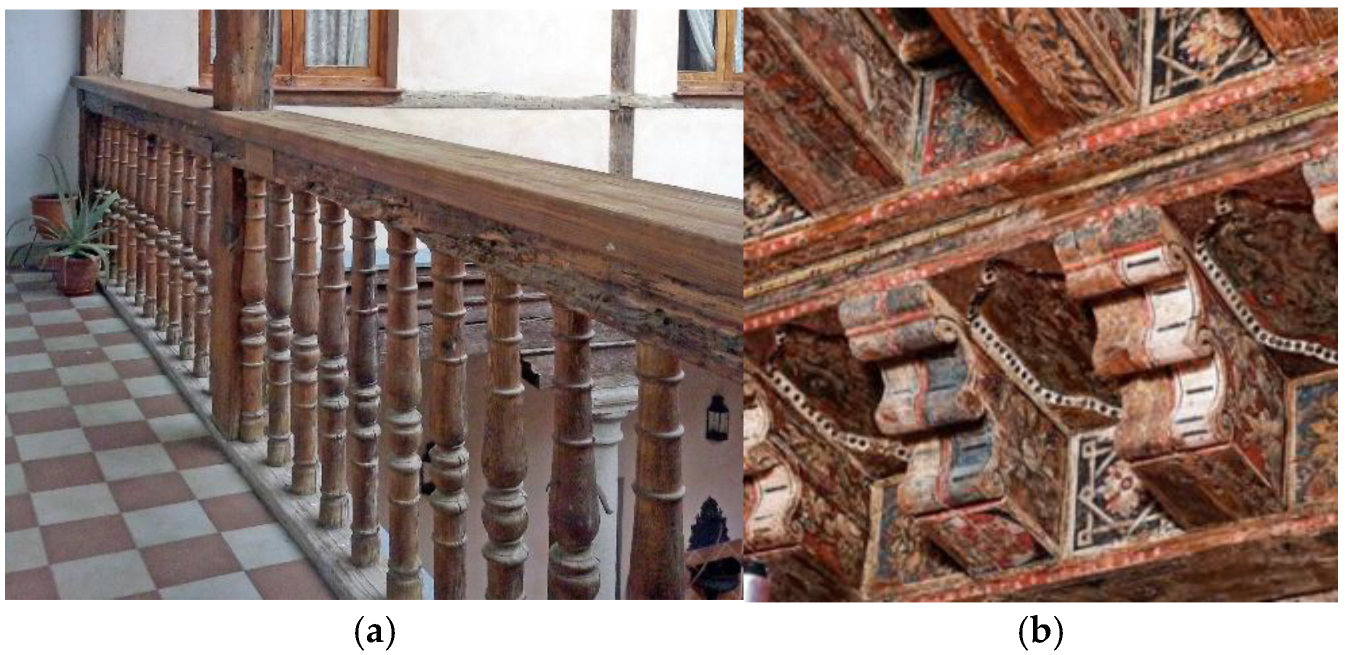

1.2.3. About 16th-Century Spanish Domestic Architecture and Its Wooden Galleries

1.2.4. About the Historical Images of the Alhambra

1.2.5. About the Graphic Reconstruction of Lost Heritage

2. Objectives and Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

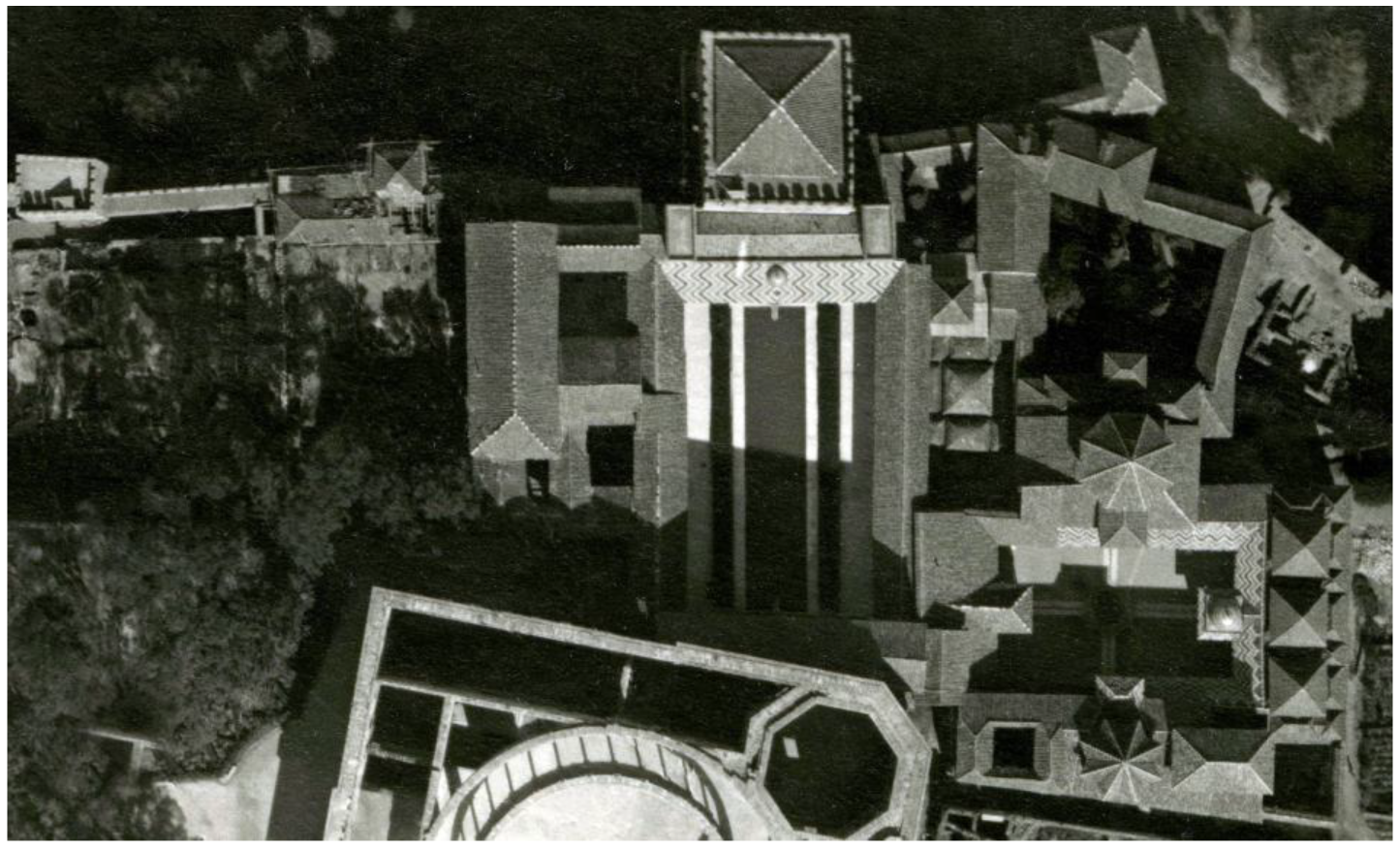

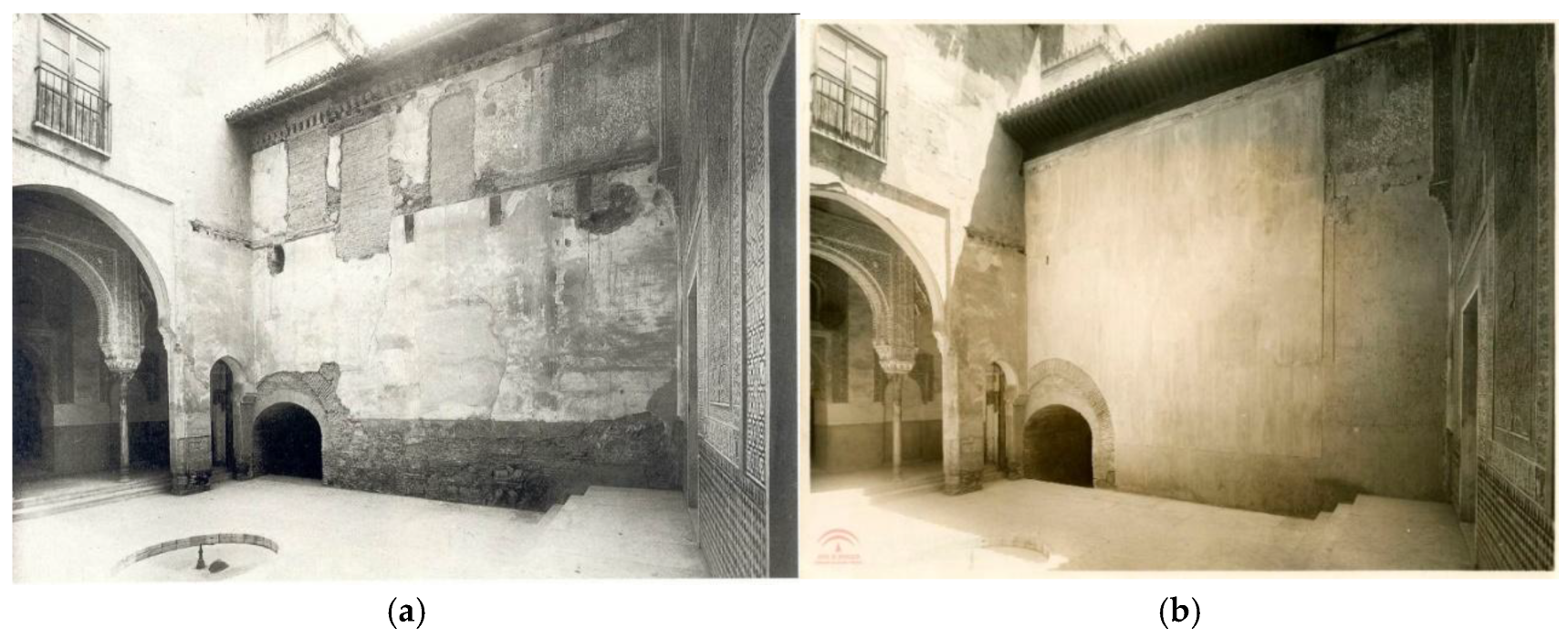

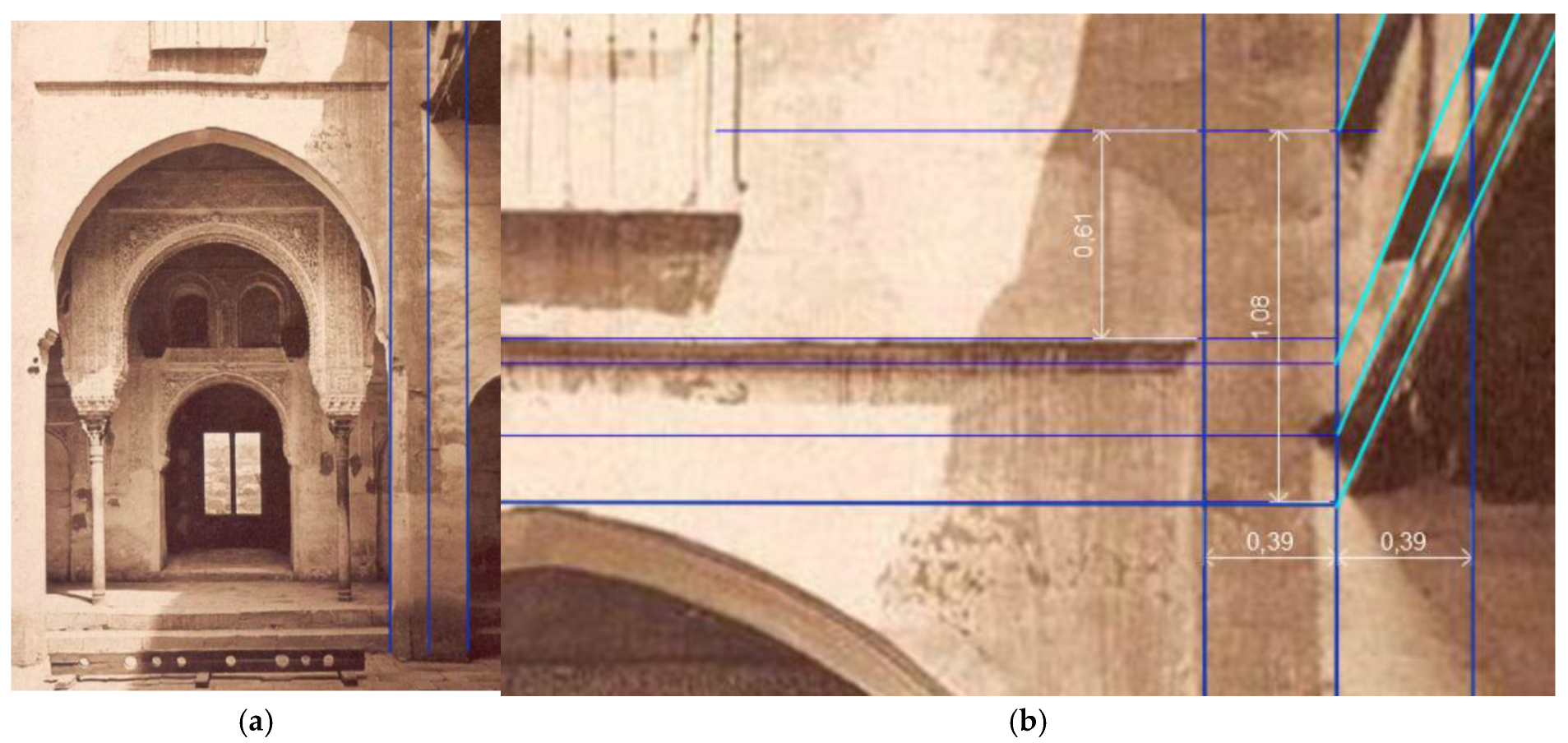

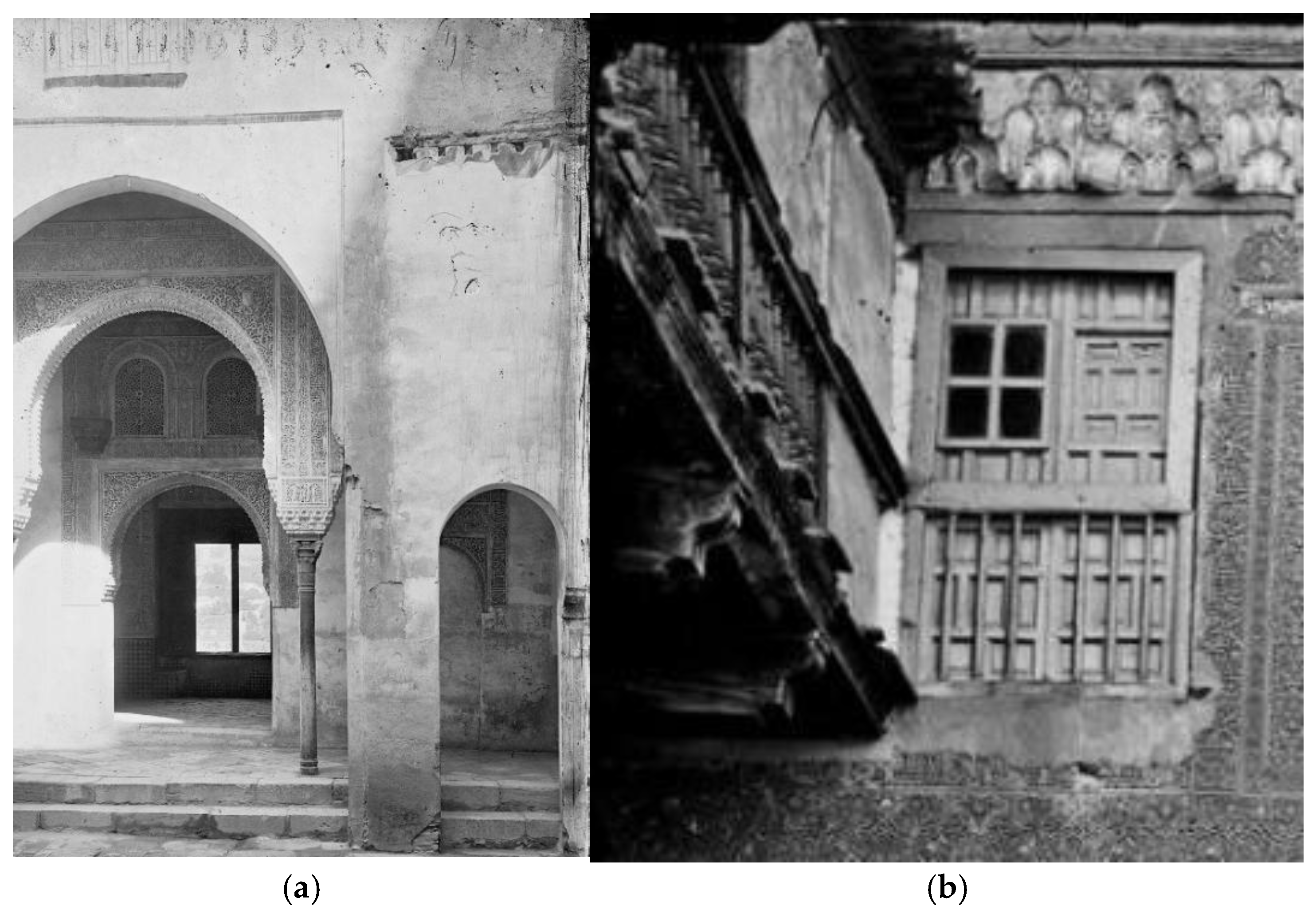

3.1. Outstanding Historical Images

3.1.1. Early Plans of the Sixteenth and Eighteenth Centuries

3.1.2. Nineteenth-Century Images

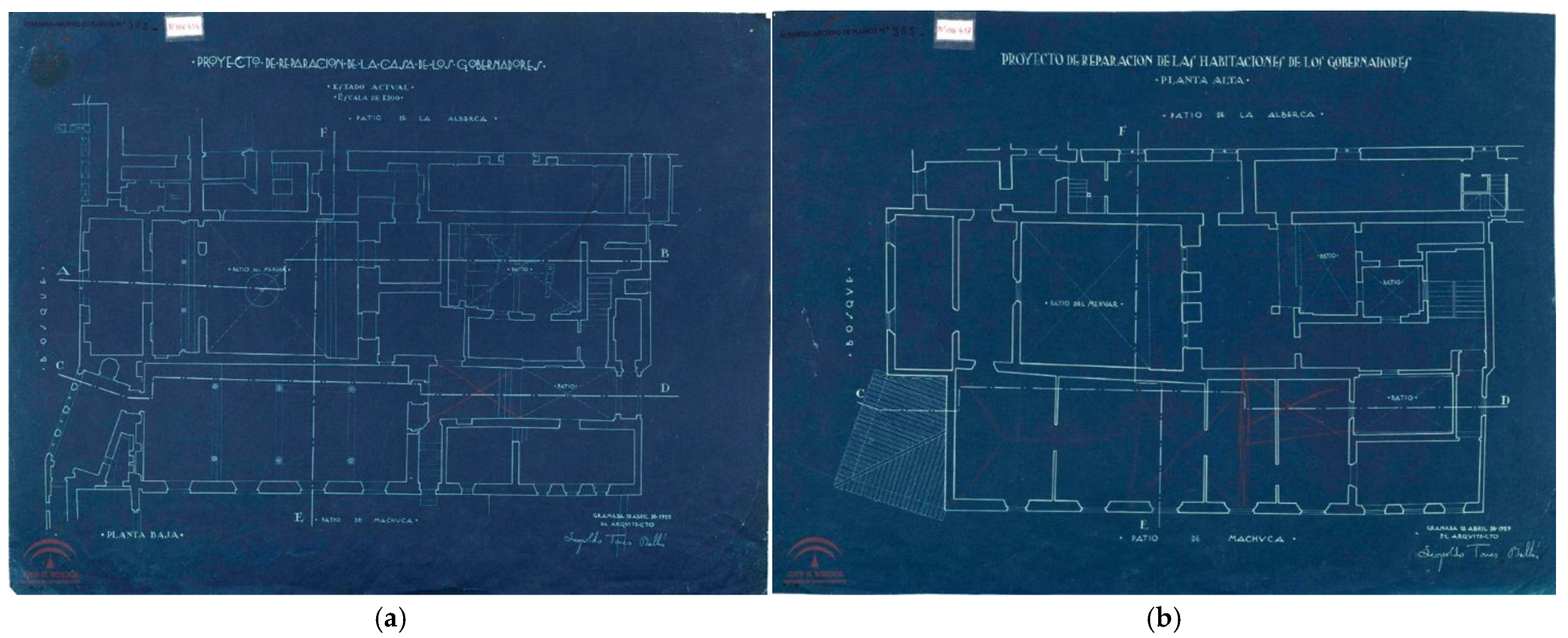

3.1.3. Plans and Photographs of the Twentieth Century

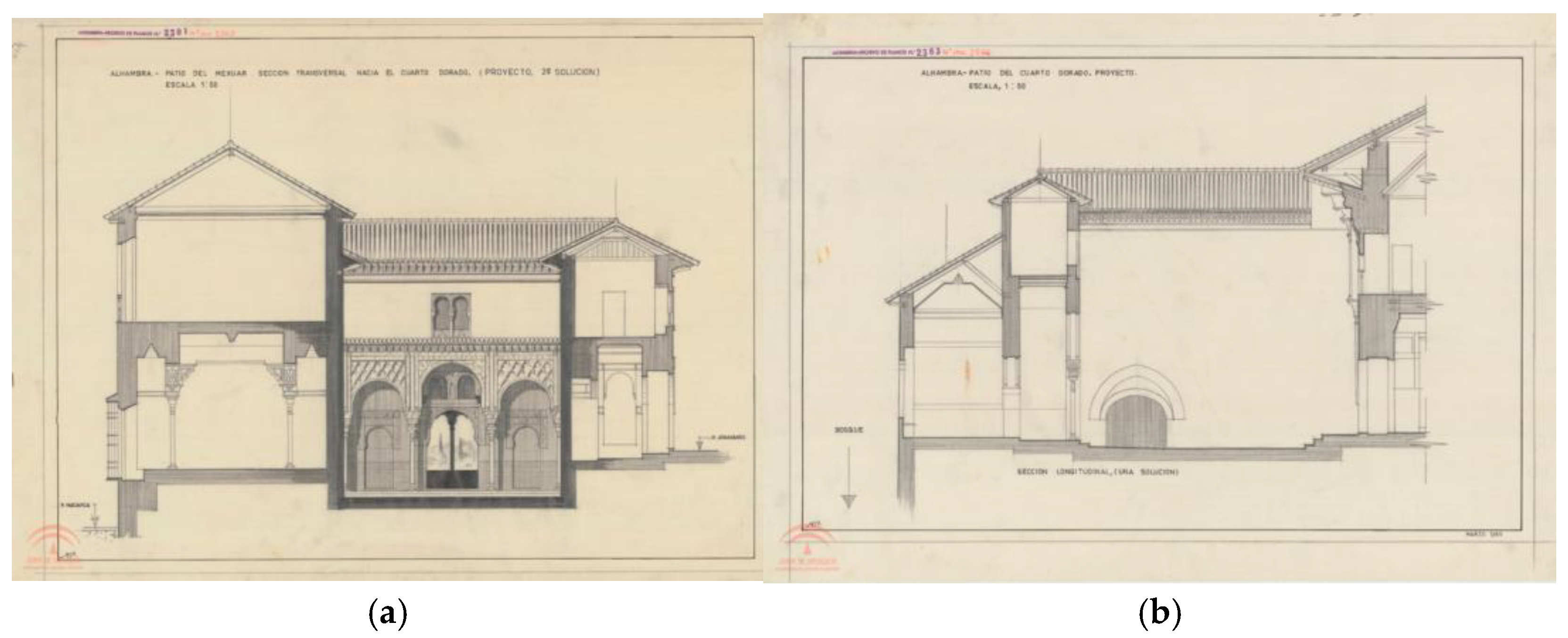

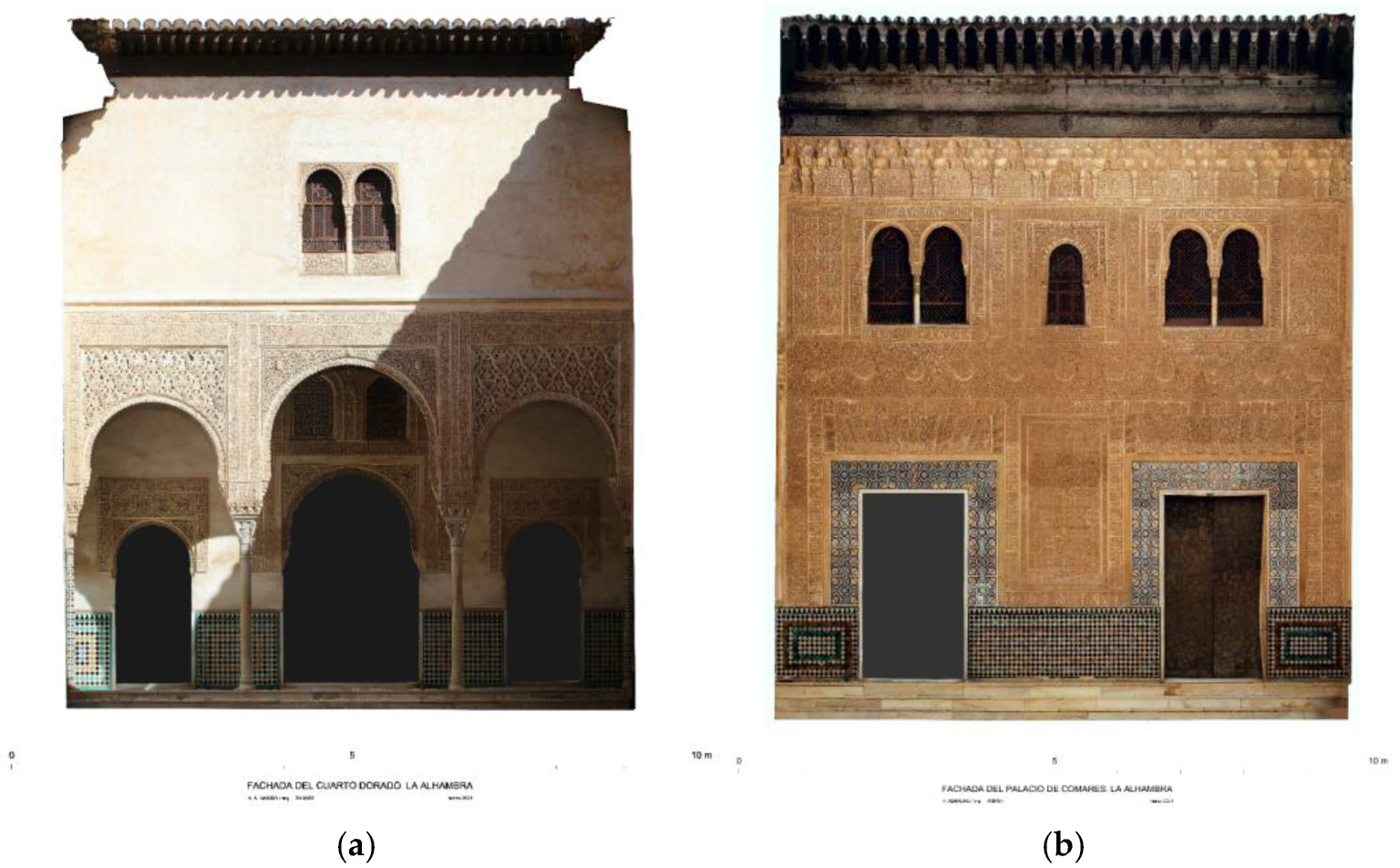

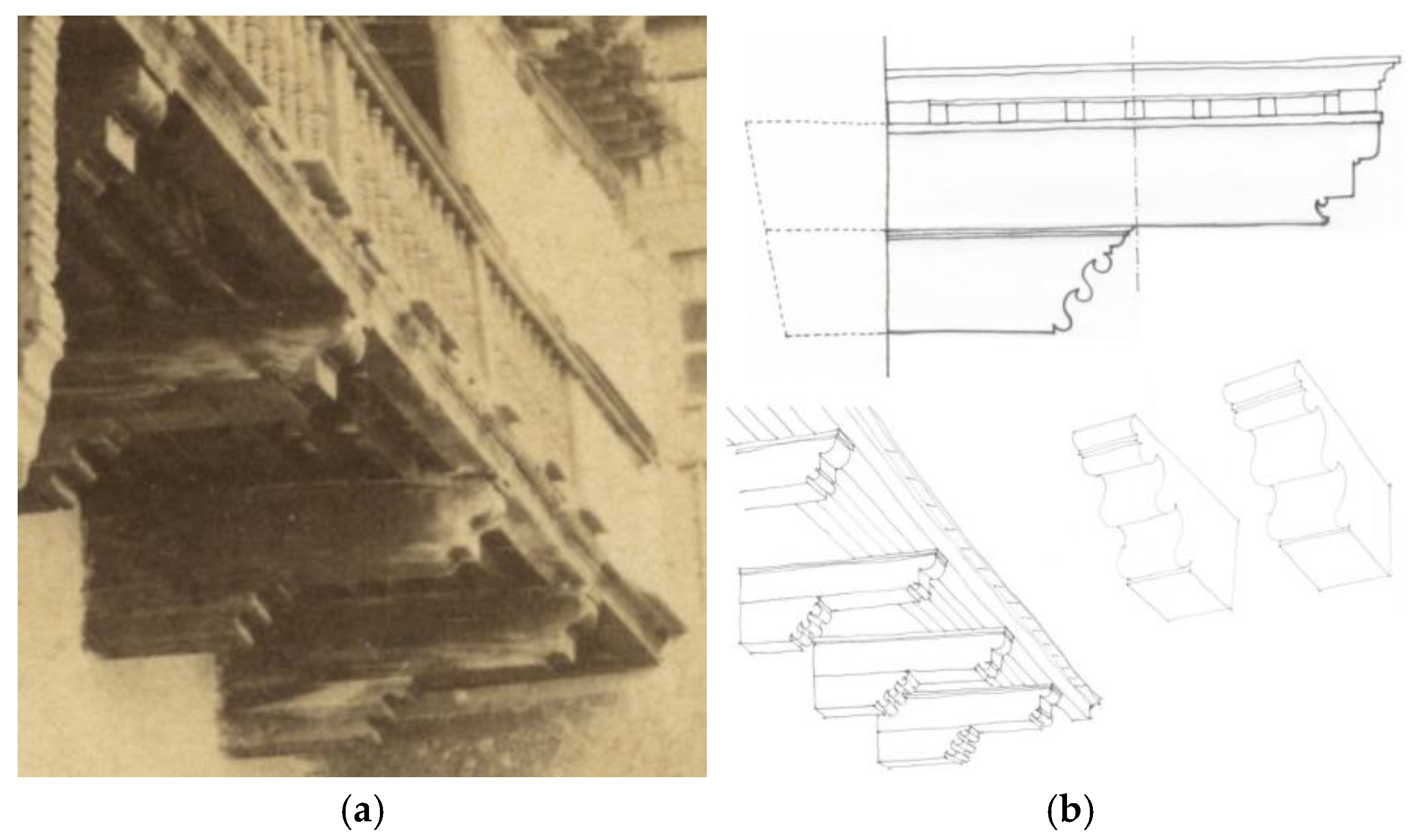

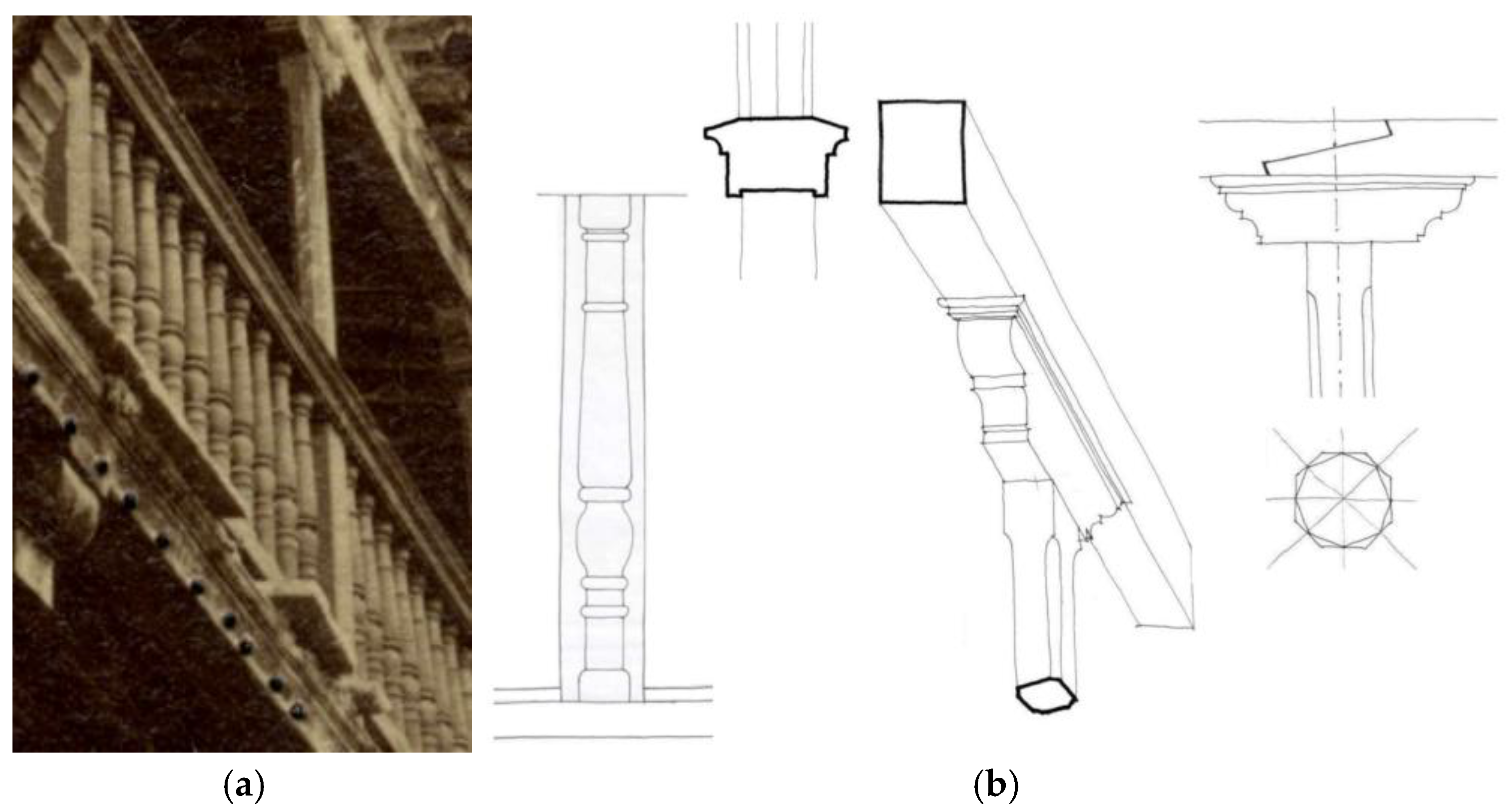

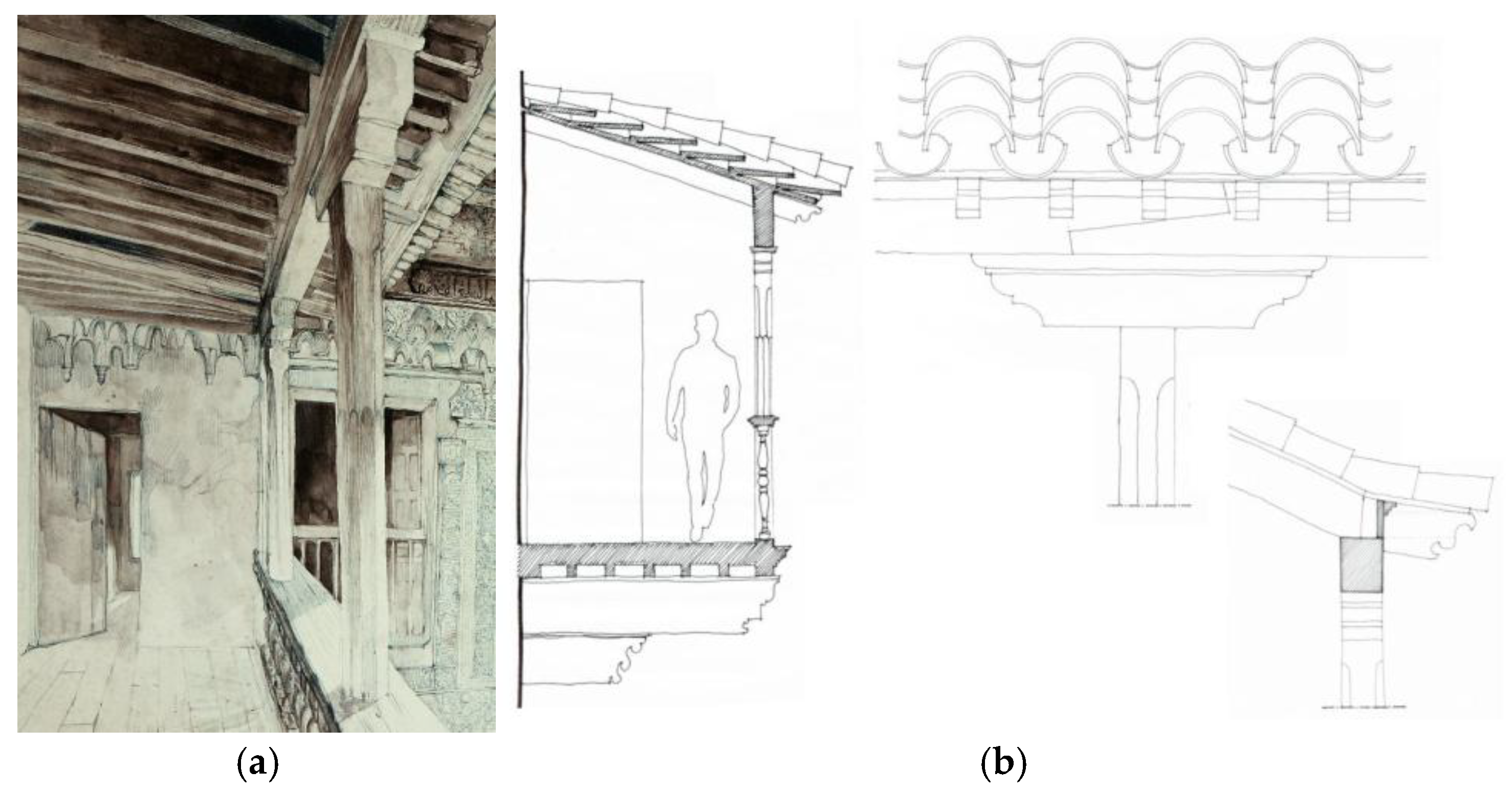

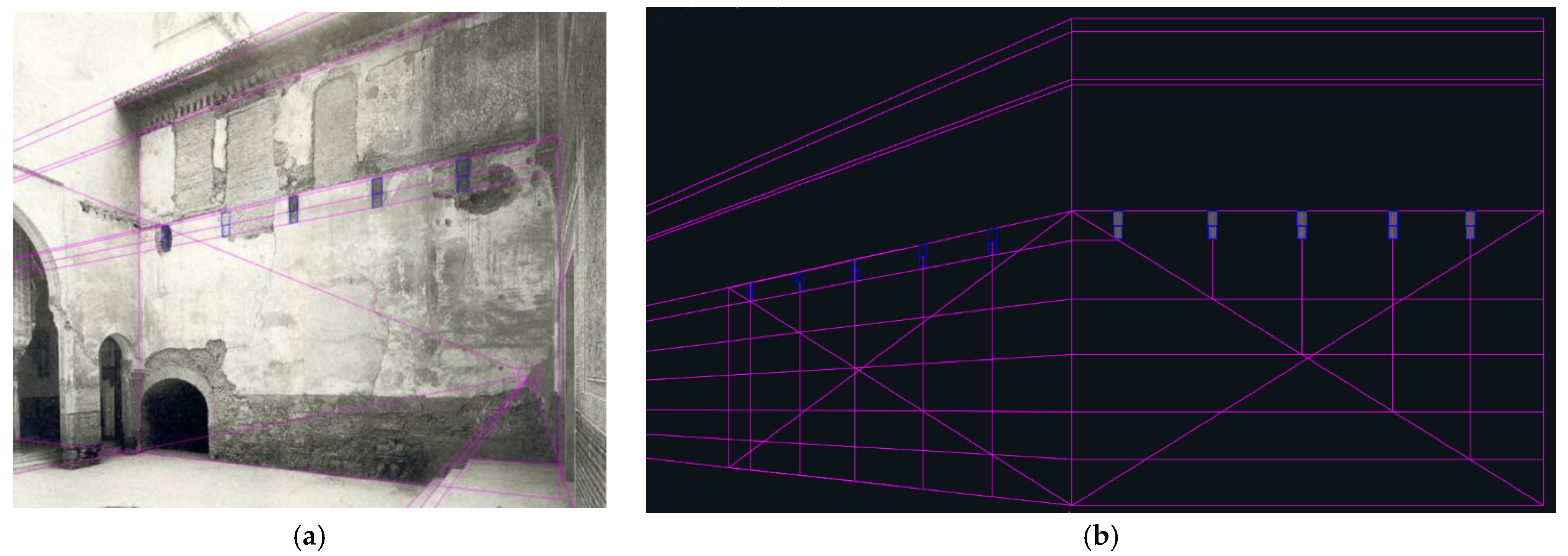

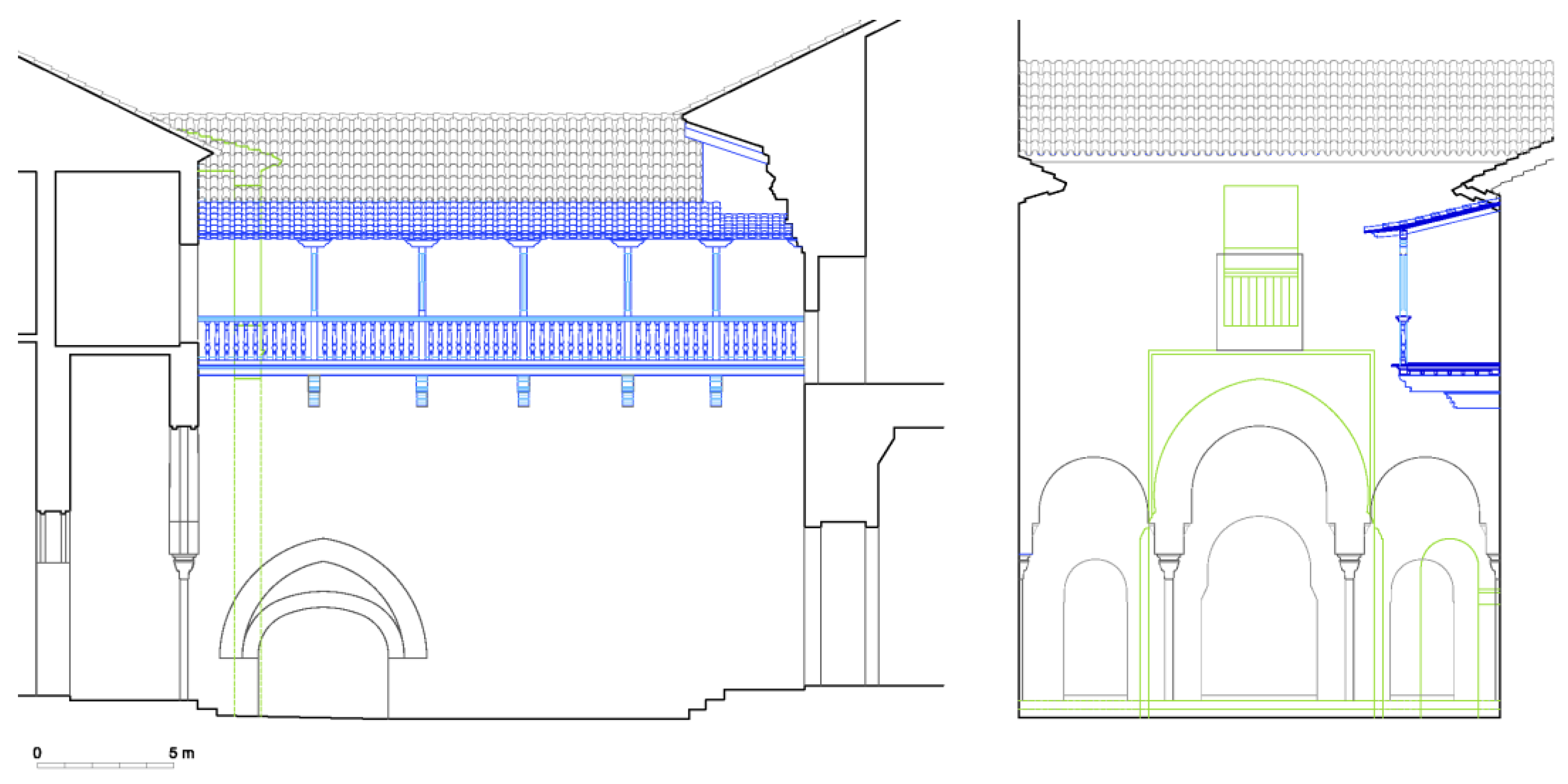

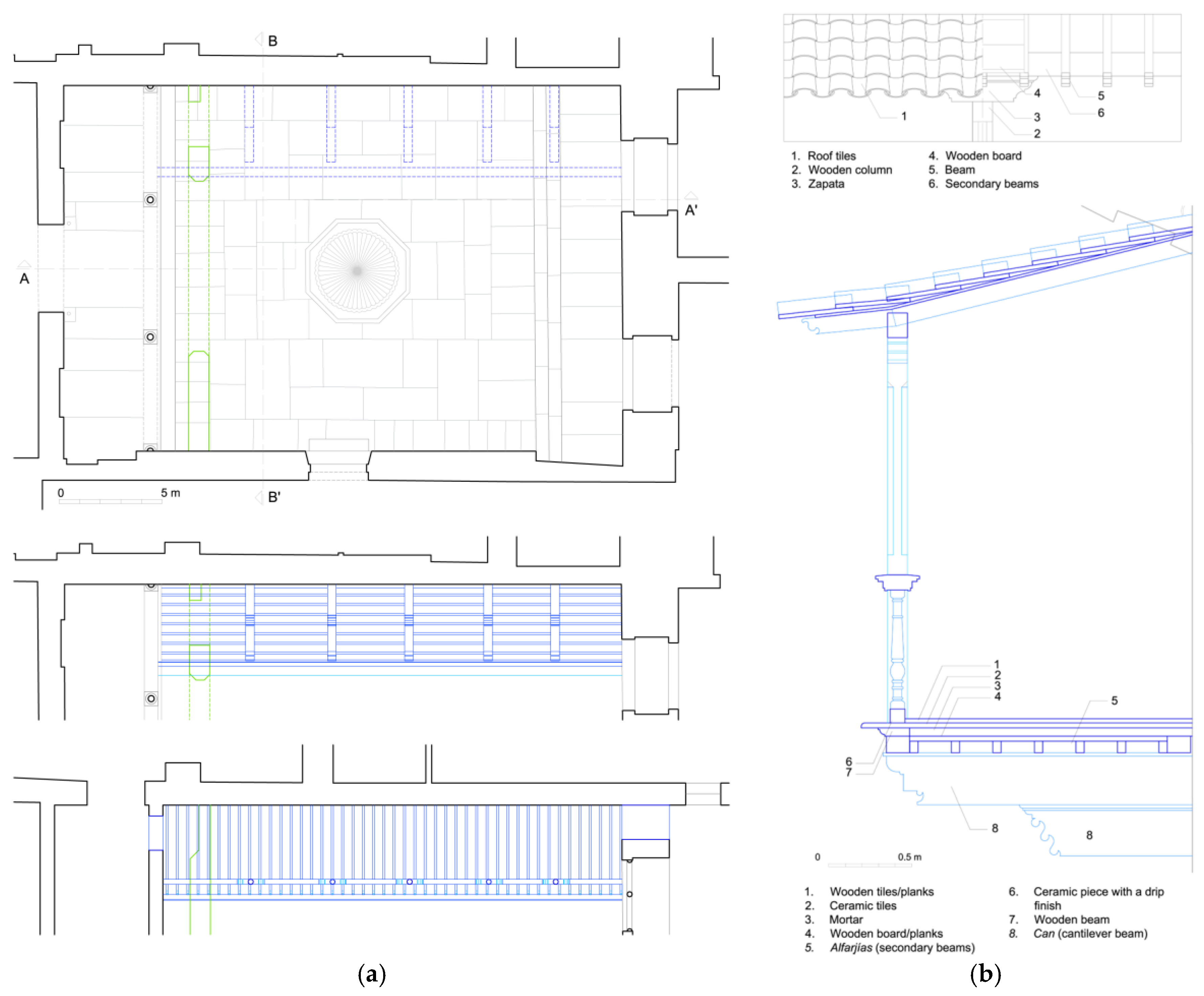

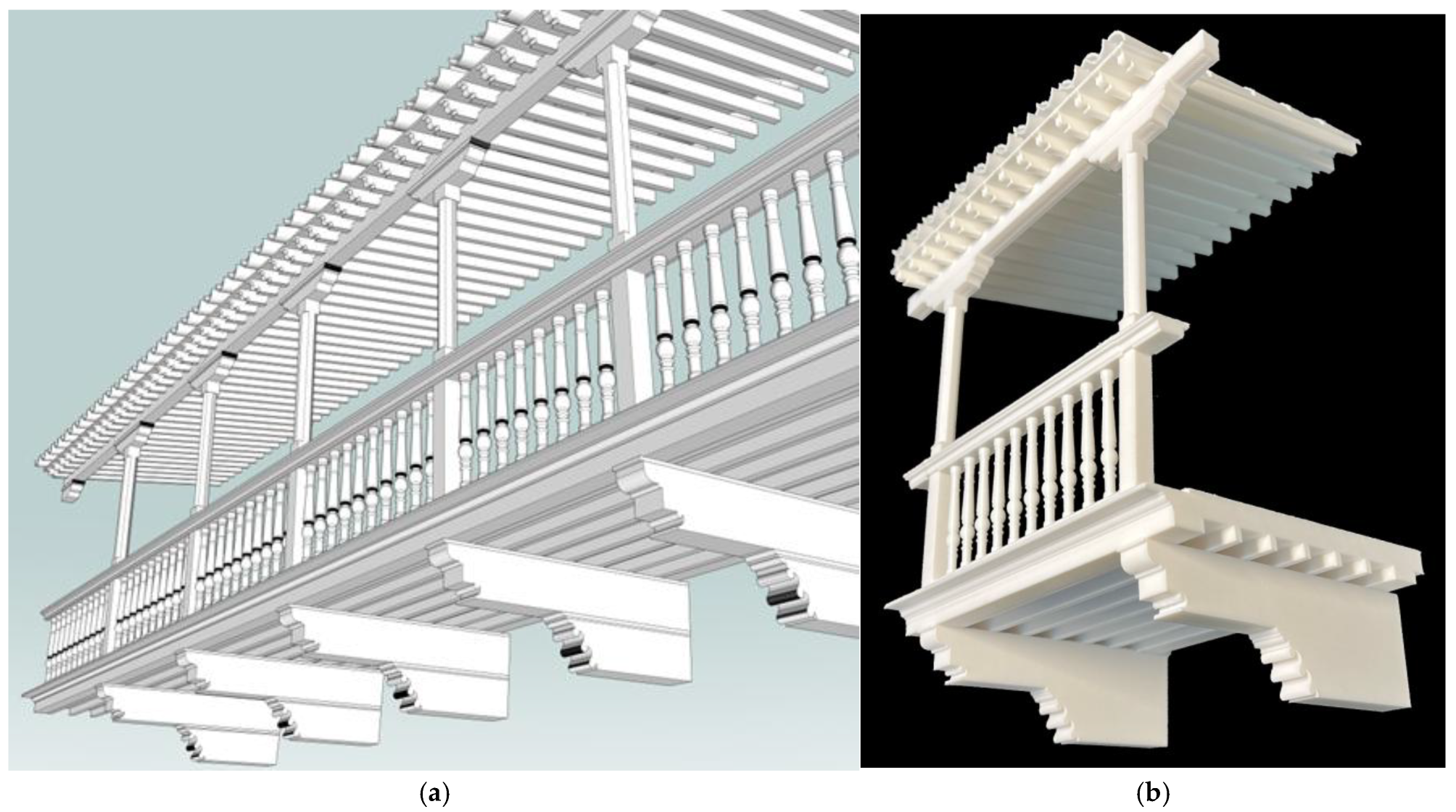

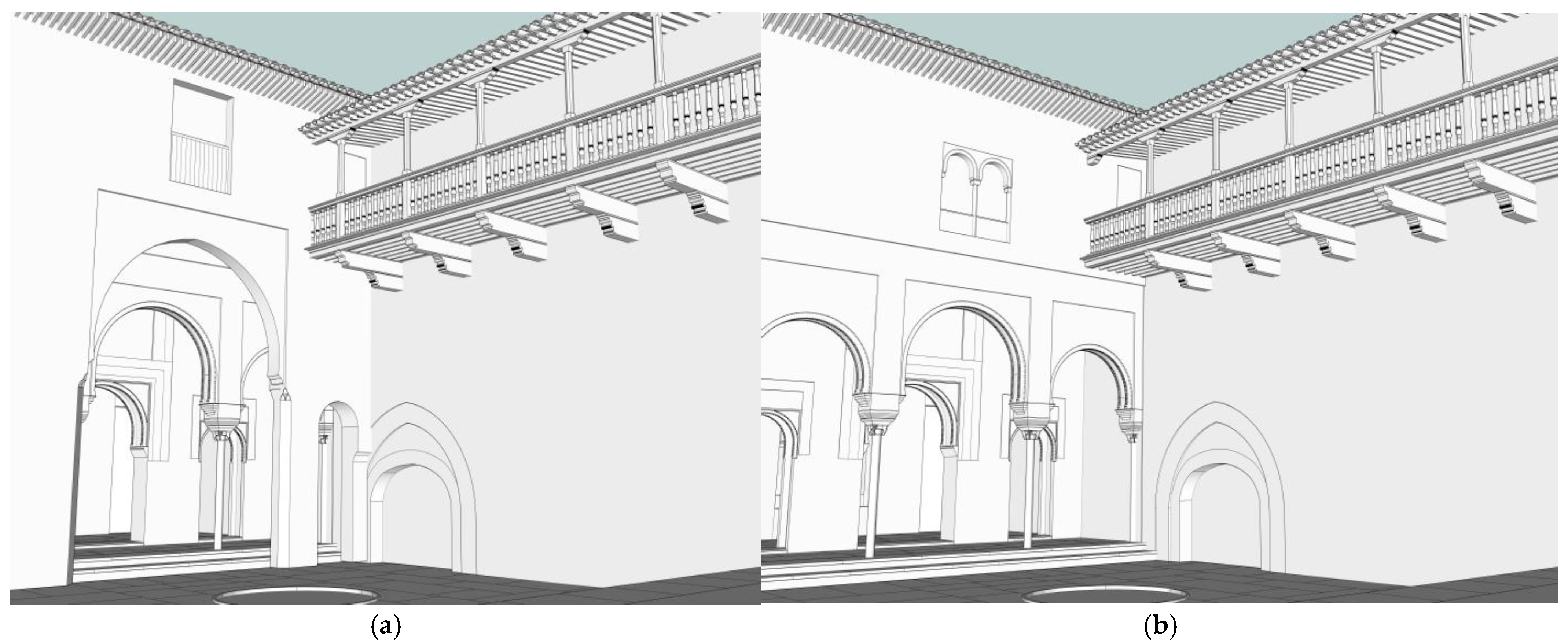

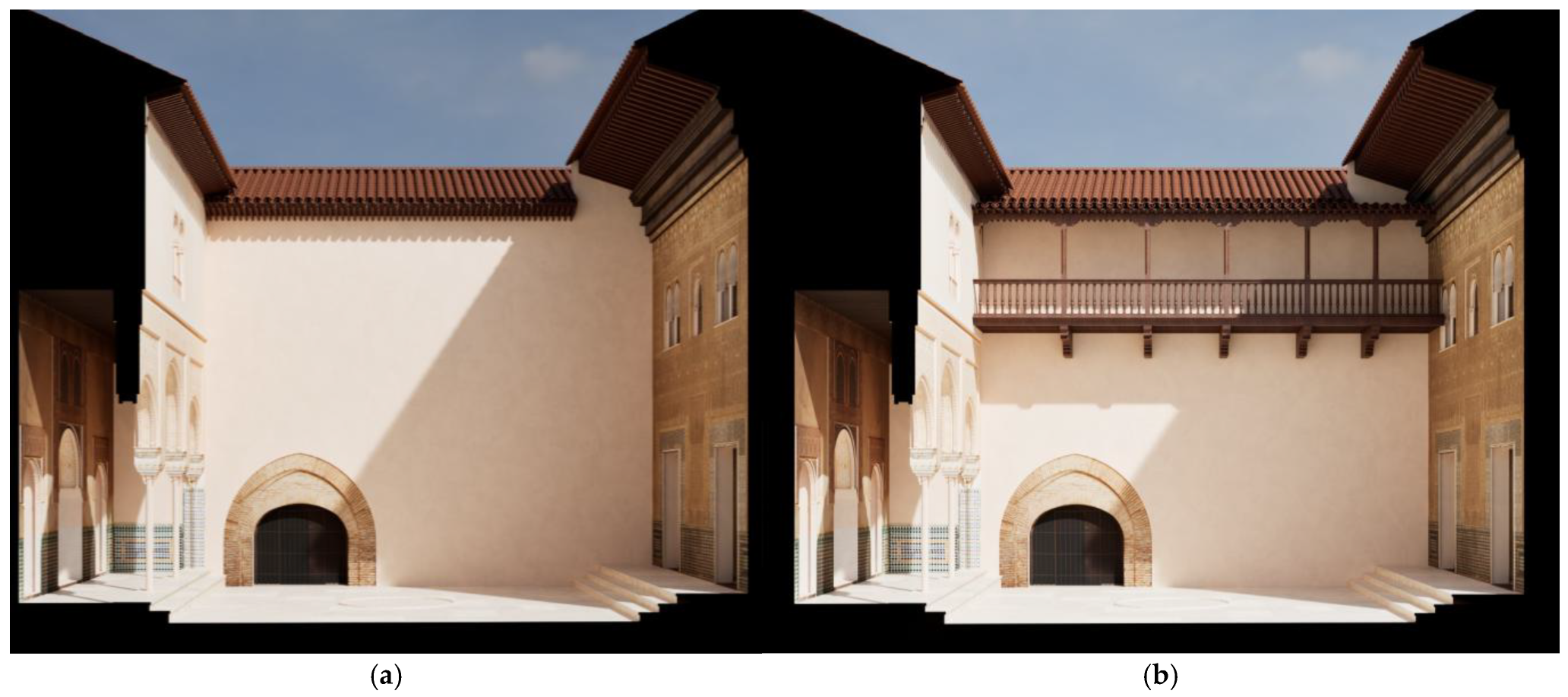

3.2. Scaled Graphic Reconstruction

3.3. Three-Dimensional Digital Representation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Alhambra, Generalife and Albayzín, Granada [World Heritage List]. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/314 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Tito-Rojo, J. Los Jardines de La Alhambra y El Generalife. I. Arte, Historia, Fantasía; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2025; ISBN 978-84-338-7561-7. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, O. La Alhambra. Iconografía, Formas y Valores; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1980; ISBN 9788420670096. [Google Scholar]

- Gámiz-Gordo, A. La Alhambra Nazarí. Apuntes Sobre Su Paisaje y Arquitectura; IUACC, Universidad de Sevilla: Seville, Spain, 2001; ISBN 8447206629. [Google Scholar]

- Suliman, A. La Organización y Funcionalidad del Espacio en la Ciudad Palatina de la Alhambra a Finales del Siglo XV; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela-Uzal, A.; López-López, Á. Una Nueva Interpretación Del Texto de Ibn Al-Jatib Sobre La Alhambra En 1362. Cuad. Alhambra 1990, 26, 121–144. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Puertas, A. La Fachada Del Palacio de Comares; Patronato de La Alhambra y Generalife: Granada, Spain, 1980; ISBN 978-8485005420. [Google Scholar]

- Universidad de Granada. Terremotos Históricos Del Sur de España. Available online: https://iagpds.ugr.es/divulgacion/terremotos/historicos (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Gámiz-Gordo, A.; Ferrer-Pérez-Blanco, I.; Reinoso-Gordo, J.F. A Deformed Muqarnas Dome at the Sala de Los Reyes in the Alhambra: Graphic Analysis of Architectural Heritage. Heritage 2023, 6, 7400–7426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Balbás, L. Los Reyes Católicos En La Alhambra. Al-Andalus 1951, 16, 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Balbás, L. Arte Almohade, Arte Nazarí, Arte Mudéjar. Ars Hispaniae: Historia Universal Del Arte Hispanico; Plus Ultra: Madrid, Spain, 1949; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre y del Cerro, A. Moros Zaragozanos En Obras de La Aljafería y de La Alhambra. Anu. C. F. Arch. Bibl. Arqueólogos 1935, 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Münzer, J. Viaje Por España y Portugal. Reino de Granada, 1494; Editorial Tat: Granada, Spain, 1987; ISBN 8477320047. [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela-Uzal, A. Casas y Palacios Nazaríes, Siglos XIII–XV; Fundación El Legado Andalusí: Granada, Spain, 1996; ISBN 9788477824084. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Cosme, A. Cuatro Siglos de Intervenciones En La Alhambra, 1492–1907. Cuad. Alhambra 1991, 27, 151–175. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Moreno-González, M. Guía de Granada; Imprenta de Indalecio Ventura: Granada, Spain, 1892. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano-Martos, R. La Alhambra: El Universo Mágico de La Granada Islámica; Grupo Anaya: Madrid, Spain, 1992; ISBN 9788420748337. [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Jorge, M.E. Los Alicatados Del Baño de Comares de La Alhambra, ¿islámicos o Cristianos? Arch. Esp. Arte 2007, 80, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casares López, M. Ciudad Palatina de La Alhambra y Las Obras Realizadas En El Siglo XVI a La Luz de Sus Libros de Cuentas. Comput. Rev. Española Hist. Contab. 2009, 6, 3–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver y Hurtado, J.; Oliver y Hurtado, M. Granada y Sus Monumentos Árabes; Impr. de M. Oliver Navarro: Malaga, Spain, 1875. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, R. Estudio Descriptivo de Los Monumentos Árabes de Granada, Sevilla y Córdoba. La Alhambra, El Alcázar y La Gran Mezquita de Occidente; Imprenta y Litografía de A. Rodero: Granada, Spain, 1878; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10514/6066 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Riaño, J.F. La Fortaleza de La Alhambra. Boletín Inst. Libr. Enseñanza 1877, XI. [Google Scholar]

- Riaño, J.F. La Alhambra. Estudio Crítico de Las Descripciones Antiguas y Modernas Del Palacio Árabe. Rev. España 1884, XVII. [Google Scholar]

- Seco de Lucena Paredes, L. La Alhambra Como Fue y Como Es; Francisco Román: Granada, Spain, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- [Exhibition Catalog]. Seco de Lucena. Un Apellido En El Periodismo Granadino; Caja de Granada/Consejeria de Cultura, Junta de Andalucia: Granada, Spain, 2002; ISBN 84-95149-36-2. [Google Scholar]

- Vílchez-Vilchez, C. La Alhambra de Leopoldo Torres Balbás: Obras de Restauración y Conservación, 1923–1936; Editorial Comares: Granada, Spain, 1988; ISBN 9788486509491. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, E.E. El Palacio de Carlos V; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1988; ISBN 9788420690407. [Google Scholar]

- López-Guzmán, R. La Arquitectura Civil En Granada En El Siglo XVI; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- García-Granados, J.A.; Trillo-San-José, C. Obras de Los Reyes Católicos En Granada (1492–1495). Cuad. Alhambra 1990, 26, 145–168. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Casas, R. Arte y Etiqueta de Los Reyes Católicos. Artistas, Residencias, Jardines y Bosques; Editorial Alpuerto: Madrid, Spain, 1993; ISBN 9788438101926. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Casas, R. Arte y Etiqueta En La Alhambra de Los Reyes Católicos. In Arte y Cultura en la Granada Renacentista y Barroca: La Construcción de una Imagen Clasicista; Cruz-Cabrera, J.P., Ed.; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2014; pp. 81–122. ISBN 9788433856906. [Google Scholar]

- Vilar-Sánchez, J.A. Los Reyes Católicos en la Alhambra: Readaptaciones Hechas por los Reyes Católicos En Los Palacios y Murallas de La Alhambra y en las Fortalezas de Granada Desde Enero de 1492 Hasta Agosto de 1500 con Algunos Datos Hasta 1505; Comares: Granada, Spain, 2007; ISBN 978-84-9836-305-0. [Google Scholar]

- Vilar-Sánchez, J.A. Murallas, Torres y Dependencias de La Alhambra: Una Revisión de Los Avatares Sufridos Por Las Estructuras Poliorcéticas y Militares de La Alhambra; Patronato de La Alhambra y Generalife: Granada, Spain, 2016; ISBN 978-84-9045-399-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Iturriaga, M. Asimilando El Legado Nazarí. La Evolución de La Mirada Al Paisaje Granadino a Través de Las Obras Reales En La Alhambra y El Generalife (s. XV–XVI). Arte Ciudad 2012, 18, 31–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Rozúa, J.M. Alhambra Romántica: Los Comienzos de La Restauración Arquitectónica En España; Editorial Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2016; ISBN 978-84-338-5904-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Domingo, J.M. La Restauración Monumental de La Alhambra: De Real Sitio a Monumento Nacional (1827–1907). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Espinosa, F. Arquitectura y Restauración Arquitectónica En La Granada Del Siglo XIX. La Familia Contreras. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela Uzal, A. La Conservación de Alicatados En La Alhambra Durante La Etapa de Rafael Contreras (1847–1890): ¿Modernidad o Provisionalidad? In La Alhambra: Lugar de la memoria y el diálogo; Patronato de la Alhambra: Granada, Spain, 2008; pp. 125–152. ISBN 9788498363692. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Lopera, J. La Alhambra Entre La Conservación y La Restauración (1905–1915). Cuad. Arte Univ. Granada 1977, 14, 7–238. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez Bosco, R. Plan de Conservación de La Alhambra de Ricardo Velázquez Bosco. Available online: https://www.alhambra-patronato.es/ria/handle/10514/14222 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Torres-Balbás, L.; Pita-Andrade, J.M. Diario de Obras En La Alhambra: 1923. Cuad. Alhambra 1965, 1, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Balbás, L. Diario de Obras En La Alhambra: 1924. Cuad. Alhambra 1966, 2, 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Balbás, L. Diario de Obras En La Alhambra: 1925–1926. Cuad. Alhambra 1967, 3, 125–152. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Balbás, L. Diario de Obras En La Alhambra: 1927–1929. Cuad. Alhambra 1968, 4, 99–128. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Gallardo, A. Prieto-Moreno. Arquitecto Conservador de La Alhambra (1936–1978). Razón y Sentimiento; Editorial Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2014; ISBN 9788433836050. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez-Pareja, J. Crónica de La Alhambra. Obras En El Patio Del Cuarto Dorado. Cuad. Alhambra 1965, 1, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez-Pareja, J. Crónica de La Alhambra. Obras En El Cuarto Dorado. Cuad. Alhambra 1967, 3, 179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Jorge, M.E. (Ed.) De Puertas Para Adentro: La Casa en los Siglos XV–XVI; Editorial Comares: Granada, Spain, 2019; ISBN 9788490458099. [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Jorge, M.E.; Orihuela-Uzal, A. (Eds.) Abierta de Par en Par: La Casa del Siglo XVI en el Reino de Granada; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC): Granada, Spain, 2022; ISBN 978-84-00-11103-8. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-González, M. Arquitectura, Dibujo y Léxico de Alarifes En La Sevilla Del Siglo XVI: Casas, Corrales, Mesones y Tiendas; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2021; ISBN 978-84-472-2895-9. [Google Scholar]

- Moya-Olmedo, P.; Núñez-González, M. Converso Houses in the 16th Century in the Former Jewish Quarter of Seville. Heritage 2022, 5, 4174–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passini, J. Casas y Casas Principales Urbanas. El Espacio Doméstico de Toledo a Fines de la Edad Media; Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha: Toledo, Spain, 2004; ISBN 9788484273257. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Balbás, L. Aleros Nazaríes. Al-Andalus 1951, XVI, 169–180, 365–368. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Balbás, L. Los Modillones de Lóbulos. Al-Andalus 1939, IV, 406–409. [Google Scholar]

- Los Salones Mudéjares Del Palacio Arzobispal. Available online: https://www.almamatermuseum.com/blog/2017/07/28/los-salones-mudejares-del-palacio-arzobispal/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Flores, C. Arquitectura Popular Española; Aguilar: Madrid, Spain, 1973; Volume 5, ISBN 8403809999. [Google Scholar]

- Feduchi, L. Itinerarios de Arquitectura Popular Española; Blume: Barcelona, Spain, 1978; Volume 4, ISBN 84-7031-201-4. [Google Scholar]

- La Colección de Maderas Del Patronato de La Alhambra. Available online: https://www.alhambra-patronato.es/la-coleccion-de-maderas (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- López-de-Arenas, D. Breve Compendio de la Carpintería de lo Blanco y Tratado de Alarifes; Printed by Luis Estupiñan: Seville, Spain, 1633. [Google Scholar]

- Nuere-Matauco, E. La Carpinteria de Armar Española; Munillaleria Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2011; ISBN 978-84-89150-37-9. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS [International Council of Monuments and Sites]. Colloque Sur Le Centre de Documentation de l’ICOMOS/Conference on the ICOMOS Documentation. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/116-english-categories/resources/publications/382-colloque-sur-le- (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Ortega Vidal, J.; Martínez Díaz, Á.; Muñoz de Pablo, M.J. El Dibujo y Las Vidas de Los Edificios. EGA. Rev. Expresión Gráfica Arquit. 2011, 16, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagro-Gorbea, A. Una Visión Virtual de La Arquitectura de Al-Andalus. Quince Años de Investigación En La Escuela de Estudios Árabes. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2011, 2, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámiz-Gordo, A. Alhambra. Imágenes de Arquitectura. Aproximación Gráfica a La Evolución de Su Territorio, Ciudad y Formas Arquitectónicas. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gámiz-Gordo, A.; García-Ortega, A.-J. The Palace of Charles V in the Alhambra: Graphic Analysis of the ‘Large Plan’ (circa 1532). Built Herit. 2024, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Las Antigüedades Árabes de España; Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando: Madrid, Spain, 1787; Volume 1.

- Rodríguez Ruiz, D. La Memoria Frágil, José de Hermosilla y Las Antigüedades Árabes de España; Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 1992; ISBN 978-84-7740-058-5. [Google Scholar]

- Goury, J.; Jones, O. Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra, from Drawings Taken on the Spot in 1834 by Jules Goury, and in 1834 and 1837 by Owen Jones; Owen Jones: London, UK, 1842; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gámiz-Gordo, A.; Ferrer-Pérez-Blanco, I. A Grammar of Muqarnas: Drawings of the Alhambra by Jones and Goury (1834–1845). VLC Arquit. Res. J. 2019, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Vidal, J. Monumentos Arquitectónicos de España. Palacio Árabe de La Alhambra; Instituto Juan de Herrera: Madrid, Spain, 2007; ISBN 9788497282574. [Google Scholar]

- Archivo de Planos de La Alhambra y Generalife. Available online: https://www.alhambra-patronato.es/ria/handle/10514/16 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Seguí Pérez, J. Plan Especial de Proteccion y Reforma Interior de La Alhambra y Alijares; Geometria Monografias: Granada, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Almagro-Gorbea, A. Academia Colecciones. Almagro Gorbea, Antonio [Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid]. Available online: https://www.academiacolecciones.com/arquitectura/mostrar-autores.php?id=almagro-gorbea-antonio (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Lewis, J.F. Sketches and Drawings of the Alhambra Made during a Residence in Granada in the Years 1833–34; Hullmandells, S.A., Ed.; Hodgson, Boys and Graves: London, UK, 1835. [Google Scholar]

- Gámiz-Gordo, A. Los Dibujos Originales de Los Palacios de La Alhambra de J. F. Lewis (h. 1832–33). EGA. Rev. Expresión Gráfica Arquit. 2012, 17, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámiz-Gordo, A. Dibujos de Richard Ford En Granada. Nuevos Puntos de Vista Sobre Su Paisaje Urbano (1831–33). In La Sevilla de Richard Ford 1830–1833; Fundación el Monte: Seville, Spain, 2007; pp. 86–109. ISBN 9788484552291. [Google Scholar]

- Asselineau, L.A. L’Alhambra; Lemaitre: Paris, France, 1853. [Google Scholar]

- Piñar-Samos, J.; Sánchez-Gómez, C. Oriente Al Sur. El Calotipo y Las Primeras Imágenes Fotográficas de La Alhambra, 1851–1860; Patronato de la Alhambra: Granada, Spain, 2017; ISBN 9788486827946. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Rivero, J.A. Los Fotógrafos Lamy y Andrieu. In Una imagen de España. Fotógrafos estereoscopistas franceses (1856–1867); Fundación Mapfre/TF Editores: Madrid, Spain, 2011; pp. 81–92. ISBN 978-84-9844-342-4. [Google Scholar]

- Piñar-Samos, J.; Sánchez-Gómez, C. Luz Sobre Papel. La Imagen de Granada y La Alhambra En Las Fotografías de J. Jaurent; Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife/TF Editores: Granada, Spain, 2013; ISBN 9788486827342. [Google Scholar]

- London Charter [v. 2.1]. Available online: https://londoncharter.org/fileadmin/templates/main/docs/london_charter_2_1_es.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- ICOMOS [International Council of Monuments and Sites]. The Sevilla Principles: International Principles of Virtual Archaeology. 2017. Available online: https://icomos.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Seville-Principles-IN-ES-FR.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Pietroni, E.; Ferdani, D. Virtual Restoration and Virtual Reconstruction in Cultural Heritage: Terminology, Methodologies, Visual Representation Techniques and Cognitive Models. Information 2021, 12, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E. Digital Twins for the Automation of the Heritage Construction Sector. Autom. Constr. 2023, 156, 105073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trizio, I.; Demetrescu, E.; Ferdani, D. (Eds.) Digital Restoration and Virtual Reconstructions; Digital Innovations in Architecture, Engineering and Construction; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-15320-4. [Google Scholar]

- Virtual Archaeology Review, Special Section: ‘Computer-Based Visualization of Architectural Cultural Heritage’. Available online: https://polipapers.upv.es/index.php/var/issue/view/1365 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Lillo Giner, S.; Rodrigo Molina, Á.; Esteve Sendra, C. Metodología Para La Restitución Gráfica de Un Edificio Desaparecido. La Casa de Armas de Valencia. EGA Rev. Expresión Gráfica Arquit. 2021, 26, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet López, Á. El Hotel Florida de Madrid: La Restitución Gráfica de Una Obra Desaparecida de Antonio Palacios. EGA Rev. Expresión Gráfica Arquit. 2023, 28, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitrián Varea, C. Una Propuesta Gráfica de Restitución Espacial Del Desaparecido Palacio de La Diputación Del Reino de Aragón. El Dibujo Como Herramienta de La Historia Del Arte. EGA Rev. Expresión Gráfica Arquit. 2025, 30, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzwierzynska, J.; Prokop, A. Reconstruction of Historic Monuments—A Dual Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagro Vidal, A. El Concepto de Espacio en la Arquitectura Palatina Andalusí. Un Análisis Perceptivo a Través de la Infografía; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas: Madrid, Spain, 2008; ISBN 9788400086305. [Google Scholar]

- Jampolsky, M. Alhambra: El Tesoro Del Último Emirato Andalusí. 2024. Available online: https://www.rtve.es/play/videos/documaster/alhambra-tesoro-ultimo-emirato-andalusi/16318418/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Almagro-Gorbea, A. El Legado de Al-Ándalus: Las Antigüedades Árabes En Los Dibujos de La Academia; Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando/Fundación Mapfre: Madrid, Spain, 2015; ISBN 978-84-96406-34-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.F. The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge: Courtyard of the Alhambra: PD.4-1963. Available online: https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/image/media-11671 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Rodríguez-Barberán, F.J.; Gámiz-Gordo, A.; Robertson, I. Richard Ford: Viajes Por España (1830–1833); Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando/Fundacion Mapfre: Madrid, Spain, 2014; ISBN 978-84-96406-31-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, R. Granada. Dibujos Con Escritos Inéditos; Patronato de la Alhambra: Granada, Spain, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- [Exhibition Catalog]. Luz Sobre Papel. La Imagen de Granada y La Alhambra En Las Fotografías de J. Laurent; Sánchez-Gómez, C., Piñar-Samos, J., Eds.; Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife: Granada, Spain, 2007; ISBN 9788486827229. [Google Scholar]

- Garófano-Sánchez, R. Gibraltar, Sur de España y Marruecos En La Fotografía Victoriana de G. W. Wilson & Co.; Diputación Provincial de Cádiz: Cádiz, Spain, 2005; ISBN 8495174928. [Google Scholar]

- [Exhibition Catalog]. Tesoros Del Arte Español. Pabellón de España, Exposición Universal, Sevilla; Electa: Sevilla, Spain, 1992; ISBN 84-88045-13-1. [Google Scholar]

- El Patronato de La Alhambra Adquiere Un Cuadro de Bossuet Por 9.000 Euros. Available online: https://www.alhambradegranada.org/es/info/noticiasdelaalhambra/855.asp (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Gentil-Baldrich, J.M. Bibliotheca Geométrica: Bibliografía Histórica Para La Geometría Descriptiva y El Dibujo Arquitectónico Hasta 2001; Grupo de Investigación HUM976. Expregráfica. Lugar Arquitectura y Dibujo; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2021; ISBN 978-84-09-36137-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gámiz Gordo, A. La Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba. Fuentes Gráficas Hasta 1850. Al. Qantara 2019, 40, 135–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich Hansen—Folkeliv i Gård i Granada. Available online: https://itoldya420.getarchive.net/amp/media/heinrich-hansen-folkeliv-i-gard-i-granada-a63f46 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- [Exhibition Catalog]. Europa Und Der Orient, 800–1900; Bertelsmann Lexikon Verlag: Munchen, Germany, 1989; ISBN 9783570048146. [Google Scholar]

- Adolf Seel (German, 1829–1907) A Courtyard in the Alhambra Palace, Granada, 1873. Christie’s, 1 December 2004. Available online: https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4413175 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Simons, T. L’Espagne. Orné de 335 Gravures et Planches Par Alexandre Wagner; F. Ebhardt: Paris, France, 1881. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada, L. Pintores Españoles y Extranjeros En Andalucía; Ediciones Guadalquivir: Sevilla, Spain, 1996; ISBN 84-8093-002-0. [Google Scholar]

- [Exhibition Catalog]. Paisajes de Granada de Joaquín Sorolla; Fundación Caja Granada, Fundación Rodríguez Acosta y Ayuntamiento de Valencia: Granada, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Canon EOS R6 Mark II Body, Melville, NY, USA. Available online: https://www.usa.canon.com/shop/p/eos-r6-mark-ii (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Polycam—LiDAR & 3D Scanner for IPhone & Android (Polycam has no version number). Available online: https://learn.poly.cam (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Trimble Sketchup (version 2025). Available online: https://sketchup.com (accessed on 15 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gámiz-Gordo, A.; Kaiser, K.P.; Núñez-González, M.; Barrero-Ortega, P. The Lost Golden Room Courtyard Gallery in the Alhambra: Sources, Graphic Analysis and Digital Reconstruction. Heritage 2025, 8, 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100439

Gámiz-Gordo A, Kaiser KP, Núñez-González M, Barrero-Ortega P. The Lost Golden Room Courtyard Gallery in the Alhambra: Sources, Graphic Analysis and Digital Reconstruction. Heritage. 2025; 8(10):439. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100439

Chicago/Turabian StyleGámiz-Gordo, Antonio, Keelan P. Kaiser, María Núñez-González, and Pedro Barrero-Ortega. 2025. "The Lost Golden Room Courtyard Gallery in the Alhambra: Sources, Graphic Analysis and Digital Reconstruction" Heritage 8, no. 10: 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100439

APA StyleGámiz-Gordo, A., Kaiser, K. P., Núñez-González, M., & Barrero-Ortega, P. (2025). The Lost Golden Room Courtyard Gallery in the Alhambra: Sources, Graphic Analysis and Digital Reconstruction. Heritage, 8(10), 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100439