1. Introduction

Linear cultural heritage is a specific type of heritage that manifests as a linear or belt-shaped form in geographical space [

1]. It typically spans multiple administrative units and cultural regions [

2], encompassing historical thematic events, water conservancy and transport projects, as well as commercial and religious routes [

3]. With the increasing emphasis by UNESCO on transregional cultural heritage and the promotion of related concepts such as cultural route and heritage corridor, linear cultural heritage has gradually become a focal point in international heritage studies. Existing research primarily focuses on the functional evolution [

4], value assessment [

5,

6], spatial structure [

7], and conservation and utilization [

8] of linear cultural heritage. In practical development, many countries regard linear cultural heritage as a key driver of regional revitalization. For instance, China has implemented national strategies such as the Grand Canal National Cultural Park and Silk Road initiatives, aiming to leverage cultural heritage as a bond to promote economic growth, urban renewal, ecological restoration, and cultural rejuvenation.

Tourism, as an effective means of cultural display and experience [

9], has gradually become a focal topic in the fields of conservation and revitalization of linear cultural heritage. However, due to uneven distribution of local resources and the complexity of spatial components, linear cultural heritage faces significant challenges in rational zoning and targeted strategies during tourism utilization [

10]. Current studies have explored the suitability for tourism [

2], stakeholders [

11], and the effects and impacts of linear cultural heritage tourism [

4,

12]. Nevertheless, there remains insufficient attention paid to the spatial differentiation in its tourism development. Particularly from the perspective of coupling heritage with tourism industry elements, the characteristics and evolutionary patterns of the tourism spatial structure in nodal cities along linear cultural heritage are still not clearly understood [

13].

The rapid spatial diffusion of human activities has led to the fragmentation of natural and cultural landscapes [

14]. Conversely, the tourism space derived from linear cultural heritage offers new concepts and perspectives for resource reorganization and spatial reconstruction. These tourism spaces typically use linear cultural heritage, such as rivers (natural or artificial), mountain ranges, ancient roads, or transportation routes, as central axes [

14]. They connect and cluster surrounding recreational resources to form a chain-like geographical distribution and represent a spatial type endowed with multiple functions, including landscape protection and leisure entertainment. However, previous studies have mostly focused on analyzing specific administrative areas, scenic spots, or localized regions with defined boundaries along linear cultural heritage routes [

15]. There is a scarcity of studies revealing the overall patterns of tourism space utilization from a holistic perspective, resulting in findings that are often localized in character. Against the backdrop of growing emphasis on cultural depth and regional synergy within tourism development, linear cultural heritage tourism spaces have emerged as a significant geographical driver for regional revitalization. In-depth research on the spatial structure of such heritage not only provides theoretical foundations and management pathways for addressing cross-regional governance challenges and balancing conservation with utilization but also enhances the perceived quality and experiential value of heritage culture, ultimately facilitating the innovative transformation and sustainable development of heritage values.

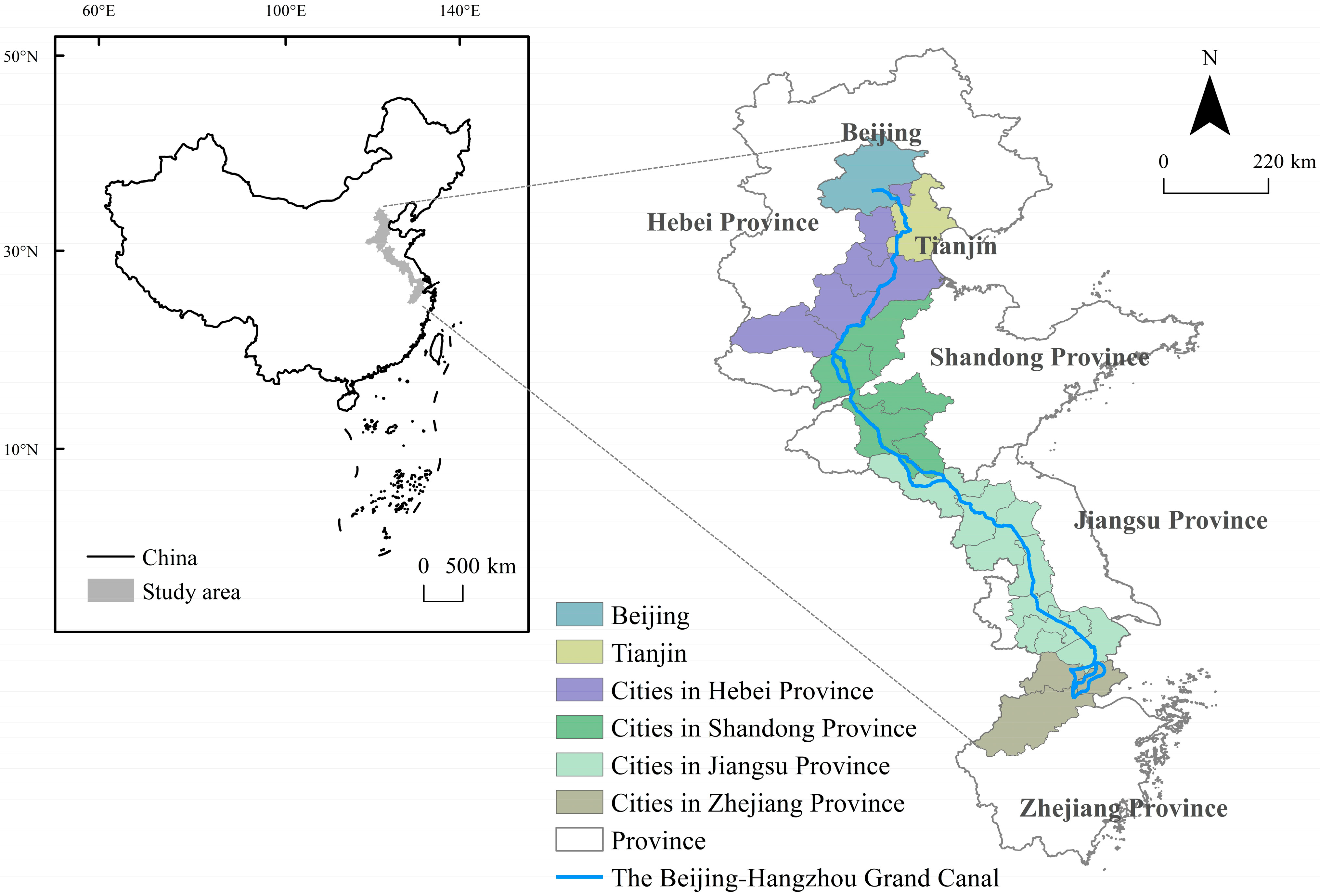

The Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal is a linear cultural heritage of great significance both in China and worldwide [

13,

16]. As the earliest built, longest, and largest artificial canal in the world, it represents outstanding premodern Chinese achievements in water transport and hydraulic engineering that were far ahead of their time. It continues to serve as irreplaceable infrastructure supporting production, living, and ecological functions and was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2014. The canal preserves rich historical and cultural relics and carries the profound cultural memory of the Chinese nation. The regions along the canal are abundant in tourism resources and possess a relatively strong economic foundation. However, like other linear cultural heritages, the tourism spaces along the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal also face challenges, such as scientific zoning and differentiated management. Studying its tourism spatial structure is essential for the orderly utilization of the canal itself and also holds important implications for the tourism revitalization of linear cultural heritages globally.

This study takes the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal as a typical case and adopts a deductive case study research approach, focusing on the systematic optimization of the tourism spatial structure of linear cultural heritage. It aims to reveal the morphological characteristics and evolutionary patterns in such tourism spaces and further explores corresponding optimization pathways. This research not only contributes to deepening the theoretical framework of linear cultural heritage—particularly by forming innovative insights regarding tourism spatial structure—but also, through the integration of empirical analysis and theory, provides a scientific basis and decision-making support for the collaborative governance and sustainable development of linear cultural heritage and cross-regional tourism spaces. It holds significant practical reference value for achieving a win–win scenario between cultural heritage conservation and regional development.

The subsequent structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 elaborates on the conceptual background and proposes the “vine-shaped structure” for linear cultural heritage tourism;

Section 3 introduces research design, data collection methods, and study area;

Section 4 analyzes optimization pathways from the perspectives of morphological decomposition and utilization intensity, supported by an empirical case study of the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal;

Section 5 discusses the theoretical contributions, practical implications, limitations, and future research directions;

Section 6 concludes with a summary of the main findings.

4. Results

Linear cultural heritage consists of diverse elements, and its tourism space also has distinct structural levels. Based on the evolutionary pattern of linear cultural heritage tourism in terms of spatial form, this study puts forward the following suggestions for optimizing its spatial structure in combination with tourism value.

4.1. Morphological Decomposition of Linear Cultural Heritage Tourism Space

4.1.1. Differentiation of “Point” Positions

Tourism points mainly refer to tourism nodes, which are the grape clusters in the “vine-shaped structure” and are generally divided by towns or tourism agglomerations. As the basic components of the tourism spatial structure of linear cultural heritage, tourism points are linearly connected resource components and are therefore often selected as the units for tourism value evaluation. For example, in this paper, each prefecture-level city along the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal is regarded as a tourism point, and its tourism values are evaluated and compared. In practice, there are tourism nodes with different types of tourism value, which require different promotion strategies. The classification and positioning of nodes along the line are prerequisites for reasonably adjusting the overall tourism spatial structure of linear cultural heritage. Generally, cities or regions with relatively high tourism value are the focus of linear cultural heritage tourism; they should leverage their strengths and avoid weaknesses to play a leading role in driving tourism along the entire line.

Secondly, the heritage resources within tourism nodes are the main tourist attractions. They form a tourism destination system within the node and continuously spread to the surrounding areas, forming a tourism hinterland and realizing a “core-periphery” integrated development model. Therefore, at the micro level of tourism nodes, identifying the tourism value of different heritage resources and grasping the interactive relationships between them are also factors that enhance the tourism value and status of the tourism node itself.

4.1.2. “Line” Connection

The “line” serves as the material supporting space for linear cultural heritage, analogous to the vine in the “vine structure”. It connects different tourism nodes, embodies the main body of the heritage, and manifests its linear nature. Axes play a crucial role in the regional tourism spatial structure. For linear cultural heritage, the axis is not only a transportation route but also a cultural thread, highlighting the heritage theme and ensuring cultural continuity. In practice, linear connection requires each node to recognize and inherit the cultural theme, establish a unified regional brand, and create a distinctive tourism and cultural image.

Furthermore, beyond the inherent heritage routes, it is also vital to connect geographically non-adjacent nodes—for instance, the cross-regional linkage between the cities at the two ends of the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal. When selecting and establishing connecting lines, full consideration should be given to the tourism value of different nodes: cities or regions with high value, as priority development nodes, will be the first choice for route construction; those with lower value will be included in subsequent development plans. Meanwhile, the close connection between linear cultural heritage tourism nodes and surrounding or other important areas is an important guarantee for expanding influence and lays the foundation for building a tourism spatial network.

4.1.3. “Area”-Shaped Networking

The “area” is an inevitable result of the spatial expansion of linear cultural heritage tourism, forming a regional surface based on the continuous extension and evolution of tourism nodes and axes. For the linear cultural heritage as a whole, the regional surface takes the “line” of the linear cultural heritage as the axis and spreads to both ends, relying on closely connected tourism nodes; in terms of the internal composition of the linear cultural heritage, the regional surface is a typical tourism agglomeration area or tourism plate formed by taking important tourism nodes as the core and connecting with adjacent nodes. A linear cultural heritage can derive multiple regional surfaces. However, in any case, the formation of the “tourism area” is inseparable from the construction of a network, emphasizing the close connection and interdependence between tourism nodes.

4.2. Utilization Intensity of Linear Cultural Heritage Tourism Space

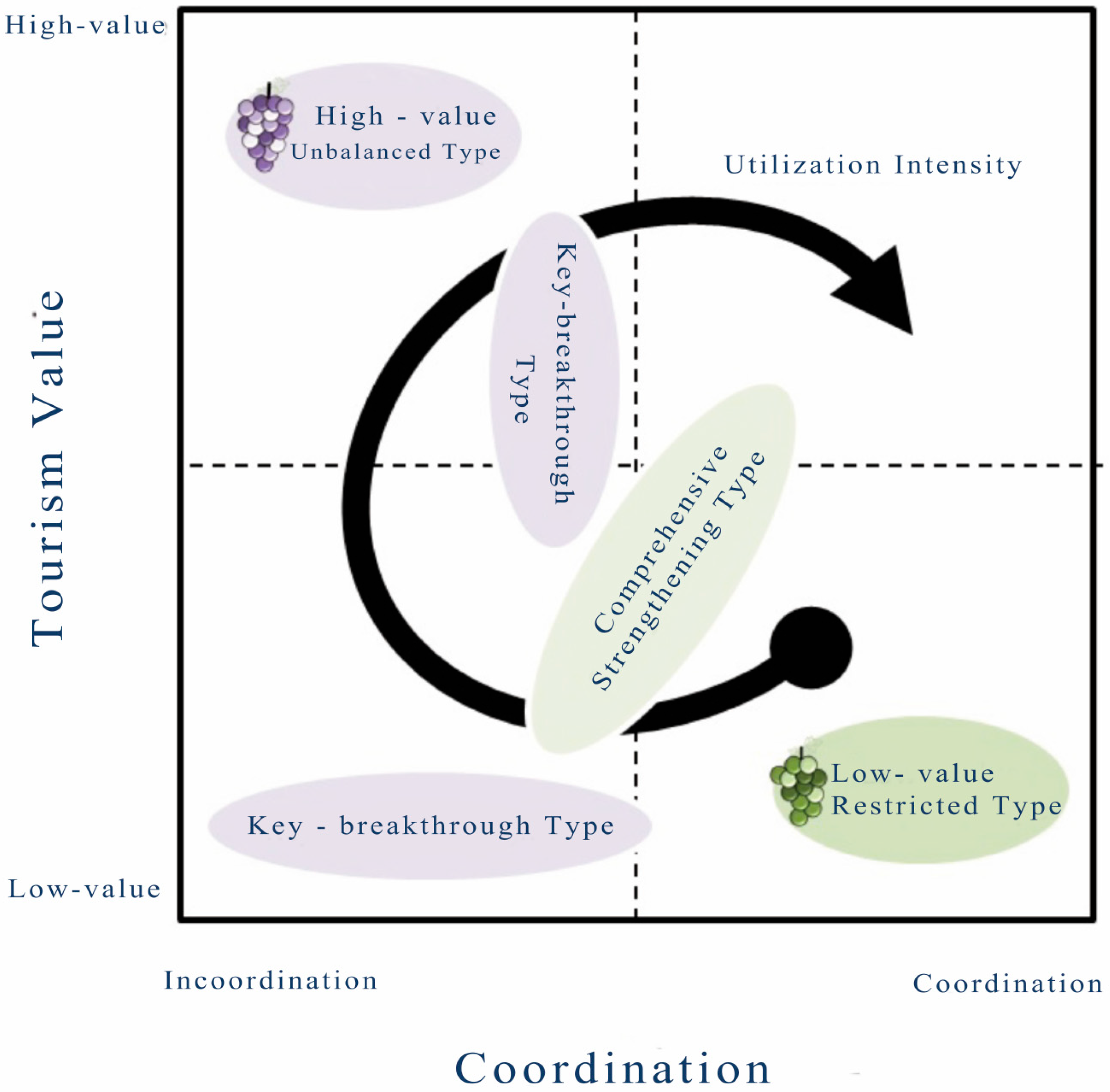

In the process of classifying tourism values, both value grades and coordination are comprehensively considered. With tourism nodes as the evaluation units, different types can be formed in the tourism value matrix (

Figure 3). Among them, the high-value unbalanced type and low-value restricted type are relatively fixed categories, while the remaining categories need to be reasonably divided according to the actual situation of linear cultural heritage. For example, cities along the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal are mainly of the key breakthrough type and comprehensive enhancement type. Admittedly, the type characterized by high value and high coordination is the optimal development state, but it is not common in reality. Both the low-value uncoordinated type and high-value uncoordinated type need targeted improvement for their main weak points.

The tourism utilization degree of linear cultural heritage is basically determined by the level of tourism value, but it is also affected by coordination, forming an unclosed circular growth model in the tourism value grid chart. As shown in

Figure 3, among the cities along the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal, the low-value restricted type should focus on heritage protection, reducing and restricting tourism utilization. Although the key breakthrough type has no particularly prominent aspects, it also has no obvious shortcomings and needs all-around development, and tourism is an effective means to drive the local economy. Therefore, the intensity of tourism utilization is at a relatively high level. However, it should be noted that the utilization intensity of the high-value uncoordinated type will be higher than that of the low-value uncoordinated type, which is caused by the shortage or poor quality of low-value tourism resources. Although the high-value unbalanced type has clear shortcomings, its prominent tourism value will bring abundant market development resources, so the tourism utilization intensity is relatively high. The most complex is the comprehensive enhancement type. Affected by the relatively low tourism value, the tourism utilization intensity of most comprehensive enhancement areas is also weak, but some areas with medium tourism value and coordination can show high utilization intensity under the stimulation of good policies or other conditions, such as Huzhou and Jiaxing.

It should be noted that the distinction of utilization intensity based on tourism value categories does not conflict with ROS, as they involve different geographical scales. Specifically, ROS is mostly aimed at a single scenic spot, with a clear scope, while this paper takes cities as the evaluation unit, covering a wider range, including multiple scenic spots or scenic areas, which is a tourism complex. Therefore, it is not that cities with high tourism value should be strictly protected and restricted from tourism development but that the excessive commercialization and tourism intervention of high-value tourist attractions or heritage sites in the city should be restricted and, finally, form a ROS multi-level nested zoning model with multiple core protected areas, mainly in the form of cultural relics protection units and A-level tourist attractions, with tourism activities developed in the periphery.

4.3. Empirical Study on Optimizing the Tourism Spatial Structure of the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal

In this study, the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal is regarded as a continuous tourism axis, with 22 cities along it serving as nodes, each forming a relatively independent tourism destination system. Based on node type, tourism value, and tourism utilization intensity, this study categorizes the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal into a three-tier tourism zone system (

Table 1). Relying on these cities, a multi-level and differentiated tourism zone system has been formed to jointly promote the regional synergistic development of linear cultural heritage tourism.

The primary tourism zone mainly includes cities south of Huai’an, representing the highest level of tourism development along the canal. This zone benefits not only from high-quality resource endowment but also from a relatively high level of socioeconomic development. Among them, Yangzhou and Hangzhou play a leading role, having developed diverse tourism experiences while ensuring effective heritage conservation. The secondary tourism zone is located in the northern section of the canal, including Beijing, Tianjin, Langfang, and Cangzhou. Its development is primarily driven by the highly developed economies of Beijing and Tianjin. It is worth noting that Langfang and Cangzhou in Hebei Province are included in this zone due to their locational advantages, aiming to enhance internal connectivity and attract external resources through regional synergy and diffusion effects, thereby fostering collaborative tourism development. The tertiary tourism zone spans the mid-section of the canal, covering cities in Shandong Province and northern Jiangsu Province. This zone requires systematic enhancement and resource integration. There is an urgent need to explore the core appeal of canal tourism in this section. While advancing heritage restoration and conservation, it is essential to increase emphasis on the tourism industry and cultural openness among cities within the zone. Additionally, due to the low potential for tourism development, Hengshui, Xingtai, and Dezhou are currently focused primarily on heritage conservation and have not been included in the aforementioned tourism zoning.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Progress Compared with Previous Studies

This study builds upon existing theoretical theories in tourism spatial structure and incorporates the distinctive attributes of linear cultural heritage to innovatively propose a vine-shaped structure. Previous studies have largely overlooked the spatial connectivity patterns inherent in large-scale, cross-regional tourism spaces due to their intrinsic cultural themes, often relying instead on growth pole evolution theory to emphasize point-to-area spatial expansion [

19,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. However, for tourism spaces derived specifically from linear cultural heritage, the inherent heritage resources—based on cultural attributes—form tourism attractions and nodes, while the cultural themes stimulate node expansion and connection rather than disorderly sprawl or arbitrary intrusion into culturally unrelated regions [

6,

9]. This constitutes the fundamental distinction from other regional tourism spatial structures. The proposition of the vine-shaped structure stems from in-depth reflection on practical development. Through abstract metaphorical analogy, it provides a spatial representation of the tourism spatial structure of linear cultural heritage. This approach not only deepens traditional geographical research’s engagement with soft cultural elements but also promotes the conservation and revitalization of linear cultural heritage.

Furthermore, as a large-scale composite destination system, the key issue for linear cultural heritage tourism space lies in effectively coordinating the relationships between the whole and its parts, as well as among the parts themselves [

13,

15]. Existing studies have explored canal tourism and its spatial structure from both holistic and sectional perspectives [

9,

19,

23], yet research on the synergistic mechanisms between integrity and regionality remains insufficient. In response, this study proposes a vine-shaped structure theoretical framework from a holistic standpoint. Within this framework, and taking into account the resource conditions and tourism utilization intensity of different urban nodes, multi-level tourism zones are identified, thereby enabling more targeted optimization strategies for each segment.

5.2. Suggestions for Optimizing Linear Cultural Heritage Tourism Space

The above findings are of great significance to the management practice of the Beijing–Hanghzou Grand Canal and linear cultural heritage tourism space. To avoid the intensification of spatial disparities in tourism development, it is necessary to utilize linear cultural heritage to strengthen the spatial connection among various tourism nodes, enhance regional collaboration, and use more developed tourism areas to support less developed ones, thereby achieving integrated tourism interaction, exchange, and coordinated development across the entire area of the linear cultural heritage [

9].

For the holistic conservation and development of linear cultural heritage, government departments should formulate a unified regional tourism planning to systematically integrate tourism resources across the entire area and implement strict management over the design, operation, and regulation of tourism products [

15]. It is essential not only to conduct zoning for protection and utilization—such as designating core zones, buffer zones, and recreation zones—based on the resource characteristics and preservation status but also to clarify the responsibilities of relevant government departments, including urban construction, cultural relics, industry and commerce, and environmental protection. Second, a regional collaborative network should be established to promote cross-regional information sharing. In terms of transportation, in addition to strengthening interregional transport links, such as aviation, high-speed rail, and highways, it is also necessary to improve the efficiency of intraregional transportation, such as optimizing urban public transit systems, including subways and buses. Regarding heritage information management, a multi-city, multi-level heritage information sharing platform should be established to enable dynamic monitoring of heritage conservation and tourism development in various cities [

33]. For academic support, it is recommended to set up a dedicated research association, organizing regular academic exchanges and discussions among cities. These measures should be promoted across all cities along the linear cultural heritage to ensure comprehensive cooperation and mutually beneficial tourism development.

For the primary tourism zone—specifically, cities located south of Huai’an along the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal—it is particularly crucial to enhance heritage conservation and establish a monitoring mechanism for heritage utilization. This zone plays a demonstrative role in tourism development and should therefore develop integrated approval and supervision systems that balance heritage protection with tourism development. On the one hand, dedicated teams should be formed to conduct regular on-site evaluations to ensure the integrity and authenticity of the heritage are effectively maintained. On the other hand, tourist demand should guide the regulation of market activities to prevent and curb excessive commercialization. Furthermore, efforts should be made to foster immersive and experiential tourism formats and advance thematic, narrative-driven tourism models. The inherent cultural themes of linear cultural heritage should be fully leveraged to systematically develop tourism routes that connect scenic spots within the zone, using thematic development to enhance industry vitality. Building on this, pilot and demonstration projects represented by cities such as Yangzhou and Hangzhou should be solidly advanced, using the leadership of these key areas to stimulate the entire tourism industry chain.

For the secondary tourism zone, specifically the cities located in the northern section of the canal, the core tasks for future tourism development lie in actively advancing the restoration of the heritage landscape and conducting in-depth exploration and interpretation of its cultural value. For instance, systematically compiling historical documents of the vanished river sections in Beijing can help restore the dynamic, linear characteristics of the canal, thereby enriching the heritage narrative and enhancing its tourism appeal [

11]. Second, efforts should be strengthened in tourism promotion and marketing by shaping a distinctive and recognizable heritage tourism image to effectively increase market attractiveness and competitiveness. Consideration may be given to establishing a dedicated promotion center for linear cultural heritage tourism, which would undertake systematic planning and integrated management of heritage tourism marketing activities in the zone. Meanwhile, a multi-tiered collaboration mechanism led by the government with participation from diverse stakeholders should be established. This includes fostering cross-regional tourism enterprises and actively engaging non-governmental organizations, local residents, and other relevant parties in the tourism development process, working together to create a supportive and inclusive social environment.

For the tertiary tourism zone located in Shandong Province and the northern part of Jiangsu Province, identifying a targeted approach to tourism development based on their unique characteristics is crucial. The cities within this zone currently demonstrate limited prominence in terms of tourism value and utilization intensity, which can be partly attributed to unclear self-positioning [

6,

7]. Taking Liaocheng as an example, although it has the first specialized museum of the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal culture, as well as dedicated research institutions and academic programs, its canal-related tourism remains relatively unknown and lacks influence. This study suggests that Liaocheng could position itself as a window for cultural exhibition and academic research on the Grand Canal, leveraging its strengths in canal culture studies to establish a distinctive image in the market. Furthermore, strengthening the systematic management of heritage is fundamental to preserving the cultural continuity of these cities. In addition to multifaceted documentation and registration efforts—including textual records, video archives, and online databases—it is essential to strictly address violations such as unauthorized construction and garbage dumping that damage heritage sites, thereby safeguarding the physical condition of existing relics [

16]. Finally, the establishment of a special government fund dedicated to collaborative linear cultural heritage tourism initiatives is recommended. This fund could support projects focused on heritage revitalization, cultural product development, tourism promotion, and talent cultivation, thereby accelerating market development through financial assistance.

5.3. Limitations of the Study

This study has several limitations. First, the case study method adopted is based on deductive reasoning and relies primarily on qualitative analysis, lacking quantitative verification of the research framework and conclusions. Second, using only the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal as an empirical case may limit the generalizability of the findings to other types of linear cultural heritage, such as road systems, military engineering projects, and historic trade routes. Third, the classification of tourism value applied in this study draws on existing literature, which may not align perfectly with the specific context of this research. Fourth, the proposed strategies could encounter challenges during implementation, including coordination difficulties among government bodies and enterprises, as well as interregional collaboration barriers. Therefore, future research should incorporate more diverse case studies and quantitative methods to validate the theoretical framework and develop a classification system better suited to the objectives of this study. Furthermore, systematically evaluating the feasibility and practicality of the proposed strategies represents an important direction for subsequent research, which would help foster broader support for these recommendations.

6. Conclusions

This study, based on the unique attributes of linear cultural heritage, innovatively proposes a “vine-shaped” tourism spatial structure suitable for such heritage from the perspective of spatial differentiation and clarifies spatial optimization pathways in terms of both spatial form and utilization intensity. Using the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal as a case for empirical validation, a multi-level tourism zone system was established, and targeted enhancement strategies were proposed accordingly.

Although this study has certain limitations in quantitative validation, its main findings still offer valuable insights for other linear cultural heritage sites facing challenges in heritage reuse and tourism development. In particular, the vine-shaped structure derived from a holistic perspective, along with tailored optimization strategies for different zones and nodes, supports the coordinated development between the whole and parts, as well as among the parts themselves, along linear cultural heritage. This research not only expands traditional tourism geography’s engagement with soft cultural elements but also provides theoretical and practical support for the conservation and revitalization of linear cultural heritage.