Museums and Urban Sustainability: A Comparative Study of Athens and Singapore

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Culture and Urban Sustainable Development

2.2. Define the Role of Museums

3. Methodology

3.1. Selection of the Case Studies

3.2. Case Study and Comparative Analysis

4. The Case Studies in Brief

4.1. Athens—Introduction to the Acropolis Museum

4.1.1. The Museum as a Social Agent

Accessibility and Amenities

Seminars and Programs

Environmental Orientation

Digital Innovation

Architectural Salience and Identity

4.2. Singapore

Introduction to the ArtScience Museum

4.3. The Museum as a Social Agent

4.3.1. Accessibility and Amenities

4.3.2. Environmental and Sustainability Orientation

4.3.3. Exhibitions, Programs and Workshops

4.3.4. Promoting Psychological Well-Being and Human Awareness

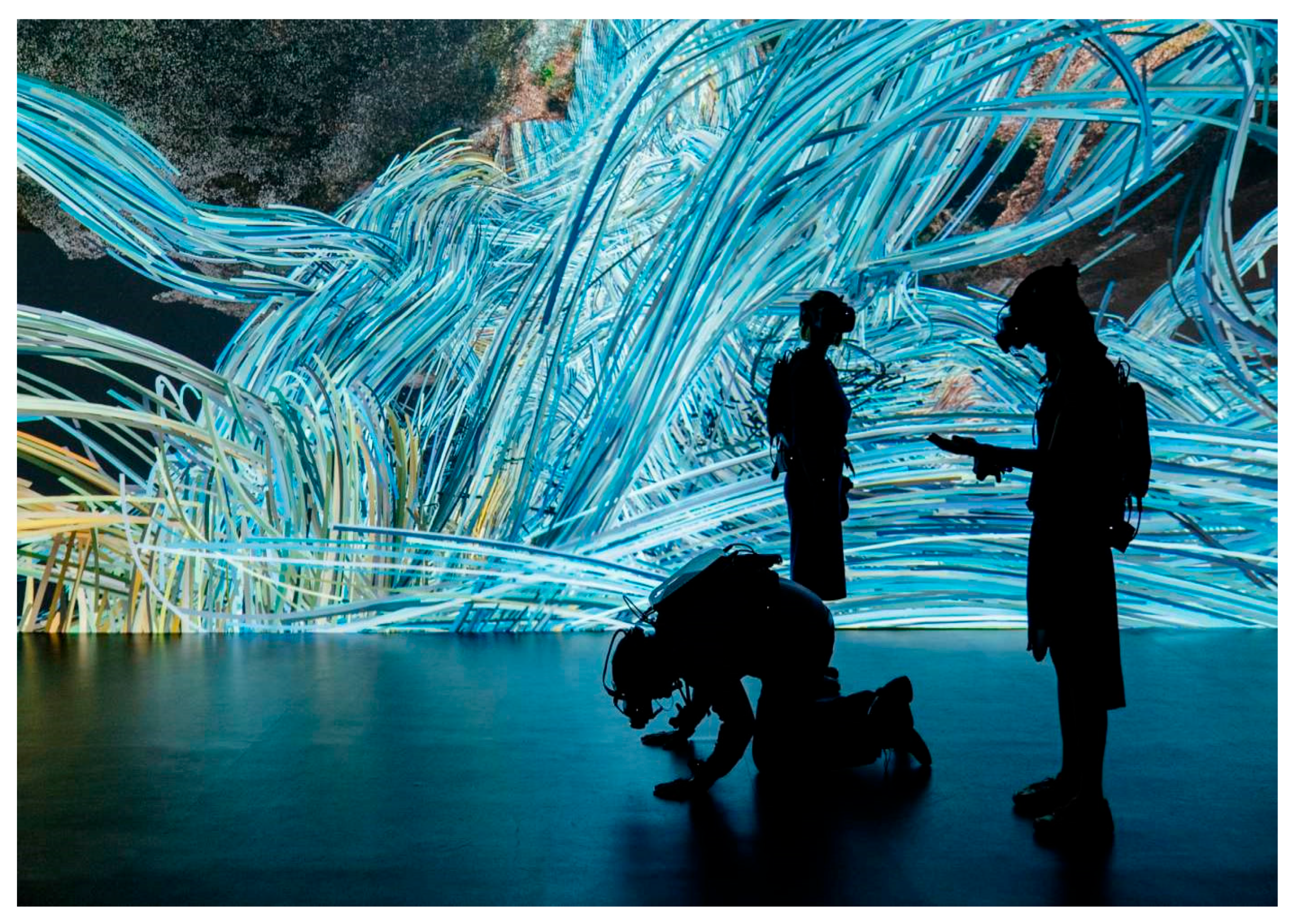

4.3.5. Digital Innovation

4.3.6. Architectural Salience and Identity

5. Comparative Analysis

6. Discussion Research Questions

- RQ1: The examined case studies align with several international frameworks, including the UNESCO’s Culture for Sustainable Urban Development and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS) of the United Nations, and more specific goals 8 and 11 [135]. The examined paradigms highlight two distinct yet complementary ways through which museums influence the sustainable development of cities. In Athens, the Acropolis Museum strengthens cultural continuity by preserving and activating collective memory, while also creating a unique identity of the place. In Singapore, the ArtScience Museum operates as a space of creative convergence, where art, science, and technology intersect to support contemporary urban narratives. In a holistic perspective, these approaches illustrate the complementary range of museums function. On the one hand, the preservation of cultural heritage, and on the other hand the interdisciplinary creativity driven by innovation.

- RQ2: Museums shape and project urban identity by acting as platforms where historical narratives and cultural aspirations are articulated. The Acropolis Museum reinforces Athens’ identity as a custodian of classical heritage and serves as a visual and symbolic anchor within the city’s historic core. Its physical and conceptual alignment with the Acropolis allows it to function as a space of cultural affirmation and national representative. In contrast, the ArtScience Museum projects a future-oriented identity for Singapore. Its interdisciplinary focus, combined with iconic architecture and a diverse exhibition agenda, positions the city as a progressive, globally engaged cultural hub. Rather than grounding identity in the past, it constructs it through innovation and creative experimentation. This duality illustrates how museums can either deepen a city’s rooted identity or catalyze its reinvention—both strategies contributing to meaningful urban distinctiveness.

- RQ3: As strategic assets, museums influence both the qualitative and quantitative aspects of urban tourism. Their impact on urban tourism is a complex phenomenon shaped by their institutional positioning, program content, and their integration into broader urban development strategies. In Athens, the Acropolis Museum enhances the city’s profile as a classical heritage destination by offering a high-quality cultural experience directly tied to its archeological context. It plays an essential role in sustaining cultural tourism flows and increasing the economic value of the city’s heritage. To better understand the important role of the Acropolis and the Acropolis Museum in Athens’ tourism flows, we can examine the existing data. According to the Hellenic Statistical Authority, in 2024 the total number of museum visitors reached almost 460,000, while the Acropolis Museum alone attracted nearly 165,000 visitors, placing it first on the list. The second most visited museum, the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, recorded nearly 48,000 visitors, followed by the Delphi Museum with 22,500 visitors [136]. The significant difference in the numbers clearly illustrates the strong motivational role the Acropolis Museum plays in attracting visitors to Athens.

- RQ4: The comparative analysis underscores that urban development through culture is not monolithic but context dependent. For both cities, the urban development has been shaped by their unique social, economic, environmental and spatial conditions. Athens demonstrates a model of culture-led regeneration where historical—archeological authenticity, public symbolism, and cultural diplomacy form the basis of urban development. The Acropolis Museum exemplifies how safeguarding heritage can translate into civic pride, international visibility, and cultural legitimacy. However, examining the broader cultural market of Athens reveals several challenges. The Acropolis and its Museum are among the most important cultural sites in the city, attracting high visitors’ numbers that lead to overtourism phenomena during peak season, particularly in summer, resulting in decreased visitors’ satisfaction. This highlights the urgent need for a strategic visitor management plan that promotes alternative cultural attractions in peripheral areas. That is why an effective development of public transportation network is crucial to connect these diverse points of interest without affecting negatively the visitors experience and being more environmentally friendly [137].

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ziyaee, M. Assessment of urban identity through a matrix of cultural landscapes. Cities 2018, 74, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Semantic similarities between personality, identity, character, and singularity within the context of the city or urban, neighbourhood, and place in urban planning and design. Int. Plan. Stud. 2023, 28, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.; Lu, H. City branding, regional identity and public space: What historical and cultural symbols in urban architecture reveal. GPPG 2022, 2, 203–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussaa, D. Urban Regeneration and the Search for Identity in Historic Cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Urban tourism as a special type of cultural tourism. In A Research Agenda for Urban Tourism; van den Borg, J., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2004; pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.J. The Cultural Economy of Paris. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2000, 24, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karachalis, N.; Deffner, A. Rethinking the connection between creative clusters and city branding: The cultural axis of Piraeus Street in Athens. Quaest. Geogr. 2012, 31, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiola, A.; Metaxas, T. Studying COVID-19 Impacts on Culture: The Case of Public Museums in Greece. Heritage 2023, 6, 4671–4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolaki, A.; Metaxas, T. Multiculturalism as a factor in economic development and city branding: The case of Komotini, Greece. Place Brand Public Dipl. 2024, 21, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, M. Cultural heritage as multi-dimensional, multi-value and multi-attribute economic good: Toward a new framework for economic analysis and valuation. J. Socio-Econ. 2002, 31, 529–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodach, C.; Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Cultural development strategies and urban revitalization: A survey of US cities. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2007, 13, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Devitt, A. Museums and Cultural Landscapes. Mus. Int. 2017, 69, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Deffner, A.; Metaxas, T. The interrelationship of urban economic and cultural development: The case of Greek museums. In Proceedings of the 43rd Congress of the European Regional Science Association: “Peripheries, Centres, and Spatial Development in the New Europe”, Jyväskylä, Finland, 27–30 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.-C.; Lin, S.-W. Efficiency evaluation of Asia’s cultural tourism using a dynamic DEA approach. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 84, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, K. Regional Diversity of Buddhist Heritage Tourism in South Asia and Southeast Asia. Heritage 2025, 8, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. Theme parks and museums in Asia and the Pacific region boost tourism demand in urban areas. SN Bus. Econ. 2025, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.; Xu, M.; Dong, N. Exploring the Role of Emotion in the Relationship between Museum Image and Tourists’ Behavioral Intention: The Case of Three Museums in Xi’an. Sustainability 2019, 11, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dong, R.; Zhu, Z.; Lian, A.; Cai, Y. Exploring a new model of urban sustainable development: The potential of oil tea as an ecological product in Guilin. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2025, 23, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.E.; Bui, H.T.; Ando, K. Zoning for world heritage sites: Dual dilemmas in development and demographics. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 24, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsarn, K.; Sawadsri, A.; Kritsanaphan, A.; Nickpour, F. Urban Branding Through Cultural–Creative Tourism: A Review of Youth Engagement for Sustainable Development. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adossary, M.J.; Alqahtany, A.M.; Alshammari, M.S. Cultural Heritage as a Catalyst for Sustainable Urban Regeneration: The Case of Tarout Island, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, S.L.; Hasan, S.A.; Rahim, L.A.; Ebraheem, A.K.; Al-Hussaini, Z.I.; Ebraheem, M.A.; Alkinani, A.S.; AL-Rawe, M.K.; Jassim, A.H.; Shok, M.E. Balancing Heritage Preservation and Sustainable Development in Historic Cities: A Case Study of Old Najaf in the Context of Global Best Practices. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2025, 20, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.; Shawn, P. The Contribution of Culture to Regeneration in the UK: A Review of Evidence; London Metropolitan University: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis, N.; Douglass, G. Culture and Regeneration—What Evidence is There of a Link and How Can It Be Measured? Working Paper 48; Greater London City Hall: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vickery, J. The Emergence of Culture-Led Regeneration: A Policy Concept and Its Discontents; Center for Cultural Policy Studies, University of Warwick: Coventry, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Amenta, E.; Polletta, F. The cultural impacts of social movements. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2019, 45, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanli, N.; Walters, T.; Williamson, J. You feel you’re not alone: How multicultural festivals foster social sustainability through multiple psychological sense of community. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1792–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/treaty/tec_2002/art_87/oj (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Plaza, B.; Aranburu, I.; Esteban, M. Superstar Museums and global media exposure: Mapping the positioning of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao through networks. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 30, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, B.; Tironi, M.; Haarich, S.N. Bilbao’s Art Scene and the “Guggenheim effect” Revisited. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2009, 17, 1711–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, N.; Tang, W.U. Spatial Techniques to Visualize Acoustic Comfort along Cultural and Heritage Routes for a World Heritage City. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10264–10280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.K.; Hsu, F.T.; Chao, C.F.; Chen, C.L. Sustainable Competitive Advantage of Cultural Heritage Sites: Three Destinations in East Asia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.D. Image-Based Segmentation of Cultural Tourism Market: The Perceptions of Taiwan’s Inbound Visitors. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Chi, X.; Han, H. Perceived authenticity and the heritage tourism experience: The case of Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 28, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. Interruptions: Testing the rhetoric of culturally led urban development. Urban Stud. 2005, 46, 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks-Heeg, S.; North, P. Cultural policy and urban regeneration. Local Econ. 2004, 19, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S.; Paddison, R. The rise and rise of culture-led urban regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 46, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Eli, M.U. Sustainability: Definition and five core principles, a systems perspective. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Du Cros, H. Cultural Tourism—The Partnership Between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management; The Haworth Hospitality Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Loach, K.; Rowley, J.; Griffiths, J. Cultural sustainability as a strategy for the survival of museums and libraries. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2017, 23, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou-Lambert, T.; Boukas, N.; Christodoulou-Yerali, M. Museums and cultural sustainability: Stakeholders, forces, and cultural policies. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2014, 20, 566–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Barton, D.N. Classifying and valuing ecosystem services for urban planning. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, M.; Marvin, S. Urban Ecological Security: A NewUrban Paradigm? Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Council of Town Planners. The New Charter of Athens 2003, Lisbon, 20 November 2003. Available online: https://www.ectp-ceu.eu/images/stories/download/charter2003.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Mairesse, F. The Definition of the Museum: History and Issues. Mus. Int. 2019, 71, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOM. Final Report of the Extraordinary General Assembly, ICOM Approves a New Museum Definition. Prague, Czech Republic, 24 August 2022. Available online: https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/EN_EGA2022_MuseumDefinition_WDoc_Final-2.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Ginsburgh, V.; Mairesse, F. Defining a Museum: Suggestions for an Alternative Approach. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 1997, 16, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, S.E. Rethinking the Museum and Other Meditations; Smithsonian Institute Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tufts, S.; Milne, S. Museums: A supply side perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazi, A. From the Muses to the Museum: The History of an Institution Through the Centuries. Archaeol. Arts 1999, 7, 39–46. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. Studying visitors. In A companion to Museum Studies; MacDonald, S., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2006; pp. 362–376. [Google Scholar]

- Van Aalst, I.; Boogaarts, I. From museum to mass entertainment: The evolution of the role of museum in cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2002, 9, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijman, J. Cultural globalization and the identity of place: The reconstruction of Amsterdam. Ecumene 1999, 6, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapuis, A. Touring the immoral. Affective geographies of visitors to the Amsterdam Red-Light district. Urban Stud. 2016, 54, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, C. Peking Duck as a museum spectacle: Staging local heritage for Olympic tourism. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2012, 10, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Hsu, S.Y. Why do Visitors go to Museums? The case of 921 earthquake Museum, Wufong, Taichung. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 16, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakou, E. Museums: Us, Things and Culture; NISOS Publising: Athens, Greece, 2001. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. A Bodies-On Museum: The Transformation of Museum Embodiment through Virtual Technology. Curator Mus. J. 2022, 66, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konsola, N. Cultural Development and Policy; Papazisis: Athens, Greece, 2006. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Frey, B.S.; Meier, S. The Economics of Museums, in Victor A. Ginsburg, David Throsby. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 1017–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey, B. The economic impact of museums and cultural attractions: Another benefit for community. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Association of Museums, Dallas, TX, USA, 14 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Grodach, C. Museums as Urban Catalysts: The Role of Urban Design in Flagship Cultural Development. J. Urban Des. 2008, 13, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, A.B. Cultural Industry as a development chance for Poland. In Proceedings of the Conference Organized by the Gdansk Institute for Market Economics, Warsaw, Poland, 13 June 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, M. Samuel Meyrick, the Tower Storekeepers, and the rearrangement of the Tower’s historic collections of arms and armour, c. 1821–1869. Arms Amp. Armour 2013, 10, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, J.; Munday, M.; Bevins, R. Developing a framework for assessing the socioeconomic impacts of museums: The regional value of the ‘flexible museum’. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, A.; Gerwitz, S.; Cribb, A. New Labour’s socially responsible museum. Policy Stud. 2007, 28, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G. Reinventing the Museum. Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on the Paradigm Shift; Atlantic Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2004; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, S. A Companion to Museum Studies; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2006; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Network of European Museums Association (NEMO). Follow-Up Survey on the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Museums in Europe, Final Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.ne-mo.org/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Figueira, C.; Fullman, A.R. Regenerative cultural policy: Sustainable development, cultural relations, and social learning. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2025, 31, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbato, V. Sustainable development and museum professions: A preliminary study in emerging trends and transformations. MIDAS Mus. E Estud. Interdiscip. 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errichiello, L.; Micera, R. Leveraging Smart Open Innovation for Achieving Cultural Sustainability: Learning from a New City Museum Project. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeretti, L.; Capone, F. Museums as Societal Engines for Urban Renewal. The Event Strategy of the Museum of Natural History in Florence. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1548–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, D.S.; Rajabi, M. The Restoration of St. James’s Church in Como and the Cathedral Museum as Agents for Sustainable Urban Planning Strategies. Land 2022, 11, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J. Urban tourism in New Zealand: The National Museum of New Zealand project. Tour. Manag. 1993, 14, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Chiou, S.-C. An Analysis of the Sustainable Development of Environmental Education Provided by Museums. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, C.G.; Sperlich, T.; Worts, D.; Rivard, R.; Teather, L. Fostering Cultures of Sustainability through Community-Engaged Museums: The History and Re-Emergence of Ecomuseums in Canada and the USA. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orman, N.A. Role of Modern Museums in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals: Green Museums between Conceptual and Application. J. Tour. Hotel. Herit. 2022, 5, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Málaga, L.R.; Brown, K. Museums as Tools for Sustainable Community Development: Four Archaeological Museums in Northern Peru. Mus. Int. 2019, 71, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, A. Experience in-between architecture and context: The New Acropolis Museum, Athens. J. Aesthet. Cult. 2012, 4, 18158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Borg, J. Demand for City Tourism in Europe. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 832–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellis, W.M. Application of a Case Study Methodology. Qual. Rep. 1997, 3, 1–19. Available online: http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol3/iss3/1 (accessed on 21 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, M.K. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollweck, T. Case study research design and methods, Robert, K. Yin. Can. J. Program Eval. 2015, 30, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryniarska, A. Using medical records in qualitative research. Advantages and limitations. Eur. J. Psychother. Couns. 2024, 26, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalla, M.; Metaxas, T. Good Governance, Resilience, and Sustainable Development: A Combined Analysis of USA Metropolises’ Strategies through the Lens of the 100 RC Network. Sustainability 2024, 15, 15895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Miguel-Molina, B.; de-Miguel-Molina, M.; Rumiche-Sosa, M.E. Luxury sustainable tourism in Small Island Developing States surrounded by coral reefs. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 98, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabassi, K. Evaluating museum websites using a combination of decision-making theories. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, F.; Oosterbeek, L.; Costa, C.; Ferreira, A.M. Extending and adapting the concept of quality management for museums and cultural heritage attractions: A comparative study of southern European cultural heritage managers’ perceptions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, P.; Navarrete, T.; Ogundipe, A. Museum open data ecosystems: A comparative study. J. Doc. 2022, 78, 761–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lee, J.; Hong, K. A Comparative Analysis of Museum Accessibility in High-Density Asian Cities: Case Studies from Seoul and Tokyo. Buildings 2023, 13, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolios, T. Reflections on the Economic Strategies of Private Museums. A Comparative Study of the Private Museums in Meteora 2023. Available online: https://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/record/9144893. (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- ProtoThema English. Acropolis Museum: In the List of the 20 Most Amazing Museums in the World. 20 May 2014. Available online: https://en.protothema.gr/2014/05/20/acropolis-museum-in-the-list-of-the-20-most-amazing-museums-in-the-world/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Kavoura, A.; Bitsani, E. Managing the World Heritage Site of the Acropolis, Greece. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 7, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippopoulou, E. The Acropolis Museum: Contextual Contradictions, Conceptual Complexities. Mus. Int. 2017, 69, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoulias, E.; Zounis, T.P. Cultural policy and marketing management: The case study of New Museum of Acropolis. In Proceedings of the Strategic Innovative Marketing: 4th IC-SIM, Mykonos, Greece, 24–27 September 2015; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 469–475. [Google Scholar]

- Mavragani, E. National Archaeological Museums and the growth of tourism in Greece. J. Reg. Socio-Econ. 2014, 4, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yalouri, E. The Acropolis: Global Fame, Local Claim; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.theacropolismuseum.gr (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Gkougkoulitsas, T. Cultural policy and management. The archaeological museum of the Acropolis. J. Contemp. Educ. Theory Res. 2017, 1, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D. Modernity, Community and the Landscape Idea. J. Mater. Cult. 2006, 11, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Chiappa, G.; Baggio, R. Knowledge transfer in smart tourism destinations: Analyzing the effects of a network structure. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulaki, P.; Kritikos, A.; Vasilakis, N. Digital Technology as a means of promoting cultural tourism in Greece–Case Study: Acropolis Museum. Sustain. Dev. Cult. Tradit. 2021, 1, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://artsandculture.google.com/partner/acropolis-museum (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Available online: https://acropolismuseumkids.gr/en/ (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Aspridis, G.; Sdrolias, L.; Kimeris, T.; Kyriakou, D.; Grigoriou, I. Visitor attraction Management: Is there space for new thinking despite the crisis? The cases of Buckingham Palace and the Museum of Acropolis. In Proceedings of the Cultural Tourism in a Digital Era: First International Conference IACuDiT, Athens, Greece, 30 May–1 June 2015; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Advisory Board Evaluation. 1987. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/404/documents/ (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- New Acropolis Museum Annual Report. A Highlights Report June 2019–May 2020, Copyright Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece, 2019. Available online: https://www.theacropolismuseum.gr/en/annual-report (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Paisiou, S. Four performances for the New Acropolis Museum. Geogr. Helv. 2012, 66, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.tripandtrail.com/acropolis-museum/ (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Szolomicki, J.; Golasz-Szolomicka, H. The Marina Bay Sands Complex in Singapore: A Modern Marvel of Structure and Technology. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 960, 022051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.singstat.gov.sg/find-data/search-by-theme/population/population-and-population-structure/latest-data (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Ahmad, A.A.B.A. Artscience Museum an Embedded Stand-Alone Art. J. La Multiapp 2020, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glennie, C. What Actually are Singapore’s Iconic Buildings Supposed to Look Like? CNN, 2015. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/moshe-safdie-interview-destination-singapore (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Kim, J.; Park, K. The design characteristics of nature-inspired buildings. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2018, 6, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardery, K.M. The ArtScience Museum at Marina Bay Sands. Archello, 2011. Available online: https://archello.com/project/the-artscience-museum-at-marina-bay-sands (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- CNN. ‘My Beliefs Haven’t Changed’: From Social Housing to Skyscrapers, Architect Moshe Safdie Is Still an Idealist. 23 September 2022. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/moshe-safdie-architect-singapore/index.html. (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Available online: https://www.marinabaysands.com/museum/plan-your-visit/amenities.html (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Alagöz, M. Comparison of certified „Green Buildings” in the context of LEED certification criteria. Archit. Artibus 2019, 11, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liou, Z.; Li, C. Overview of government strategies on green building in Singapore. J. Green Build. 2022, 17, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsani, N.T.; Jamshidi, H.M.; Mortazavi, M.; Eslamian, S. Water Harvesting and Sustainable Tourism. In Handbook of Water Harvesting and Conservation; Eslamian, S., Ed.; Wiley: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syiem, B.V.; Kelly, R.M.; Velloso, E.; Goncalves, J.; Dingler, T. Enhancing Visitor Experience or Hindering Docent Roles: Attentional Issues in Augmented Reality Supported Installations. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), Porto de Galinhas, Brazil, 9–13 November 2020; pp. 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.marinabaysands.com/museum/about.html (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Grincheva, N. The Form and Content of ‘Digital Spatiality’: Mapping the Soft Power of DreamWorks Animation in Asia. Asiascape Digit. Asia 2019, 6, 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.J. Embodied Futurities: Alecia Neo’s Socially Engaged Art Practice with Caregivers in Singapore. J. Public Pedagog. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.marinabaysands.com/museum/events/artscience-at-school.html (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Available online: https://www.stirworld.com/see-features-artscience-museum-in-singapore-bridges-the-gap-between-art-and-science (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Available online: https://www.marinabaysands.com/museum/exhibitions/vr-gallery.html (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Available online: https://www.marinabaysands.com/museum/events/artscience-interlude.html (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Available online: https://www.marinabaysands.com/museum/artscience-cinema.html (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Available online: https://www.marinabaysands.com/museum/events/sustainable-futures-film-festival.html (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Available online: https://www.marinabaysands.com/museum/events/artscience-at-home.html (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Latała-Matysiak, D.; Marciniak, M. The influence of the lotus flower theme on the perception of contemporary urban architecture. Space Cult. 2023, 26, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdie Architects. Artscience Museum in Singapore/Safdie Architects. Arch Daily. 2011. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/119076/artscience-museum-in-singapore-safdie-architects (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Faouri El, B.F.; Sibley, M. Balancing Social and Cultural Priorities in the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for UNESCO World Heritage Cities. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, E. Survey on Museums and Archaeological Sites Attendance. 2025. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/en/statistics/-/publication/SCI21/- (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Kranioti, A.; Tsiotas, D.; Polyzos, S. The Topology of Cultural Destinations’ Accessibility: The Case of Attica, Greece. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tian, L. Ecological Waves at Tourist Attractions on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Promote Greenness of Surrounding Vegetation. Land 2025, 14, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Frantz, M. Tourism marketing and urban politics: Cultural planning in a European capital. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 481–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Thematic Axis | Shared Characteristics—Key Strengths |

|---|---|

| Cultural Identity and Urban Integration | Both museums play a pivotal role in the promotion of cultural identity, actively contributing to the symbolic representation and urban distinctiveness of their cities. |

| Social Agent and Accessibility | Each institution is committed to social inclusion, ensuring equitable access and engaging diverse audiences through participatory and educational initiatives. |

| Environmental Orientation | Both museums integrate environmentally sustainable practices into their operational philosophy, including the use of natural resources, recycling systems, and eco-conscious architectural design. |

| Digital Innovation | The implementation of advanced digital technologies (e.g., virtual and augmented reality) enhances audience engagement and extends cultural access beyond physical boundaries. |

| Architectural Salience | Functioning as architectural landmarks, both museums embody a synthesis of form, function, and cultural symbolism, reinforcing their role as identity-shaping elements in the urban fabric. |

| Education and Cultural Promotion | Through comprehensive educational programs and digital outreach, both museums promote cultural awareness, creativity, and lifelong learning across multiple demographic groups. |

| Thematic Axis | Acropolis Museum (Athens) | ArtScience Museum (Singapore) |

|---|---|---|

| Curatorial Focus | Focuses on the archeological and historical narrative of classical antiquity, with an emphasis on cultural continuity and heritage preservation. | Embraces an interdisciplinary framework that explores the intersections of art, science, and technology within a contemporary context. |

| Ownership | Functions as a state-regulated, publicly funded non-profit institution, aligned with national cultural policy. | Privately administered and embedded within a larger commercial and touristic infrastructure. |

| Cultural and Political Engagement | Actively contributes to international debates on cultural property and restitution, notably in relation to the Parthenon Sculptures. | Engages with global challenges by curating exhibitions on sustainability, mental health, and digital futures. |

| Architectural Identity | Designed to maintain continuity with its historical surroundings, reinforcing spatial authenticity and cultural symbolism. | Features a postmodern, biomimetic structure inspired by the lotus flower, symbolizing innovation, fluidity, and ecological integration. |

| Energy Efficiency and Sustainability Infrastructure | Applies climate-adapted architectural principles, including solar orientation and sustainable materials, to reduce its ecological footprint. | Utilizes state-of-the-art environmental systems, such as rainwater harvesting, meeting high-performance green certification standards. |

| Institutional Priorities and Social Focus | Concentrates on safeguarding national identity and cultural legacy through academic research and civic engagement. | Promotes innovation, inclusivity, and environmental consciousness, fostering dialog on emergent societal concerns. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koutsoumpela, A.; Metaxas, T. Museums and Urban Sustainability: A Comparative Study of Athens and Singapore. Heritage 2025, 8, 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100397

Koutsoumpela A, Metaxas T. Museums and Urban Sustainability: A Comparative Study of Athens and Singapore. Heritage. 2025; 8(10):397. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100397

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoutsoumpela, Alexandra, and Theodore Metaxas. 2025. "Museums and Urban Sustainability: A Comparative Study of Athens and Singapore" Heritage 8, no. 10: 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100397

APA StyleKoutsoumpela, A., & Metaxas, T. (2025). Museums and Urban Sustainability: A Comparative Study of Athens and Singapore. Heritage, 8(10), 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8100397