A Systems Thinking Approach to the Development of HBIM: Part 1—The Problematic Situation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Historic Building Information Modelling

1.2. Systems Thinking

1.2.1. Justification

1.2.2. Applying Systems Thinking to HBIM

1.3. Aim and Objectives

- Establish how data are currently managed within the Heritage Community.

- Establish both current working practices within the Heritage Community and organisational features that may impose constraints on an HBIM system.

- Identify how participants perceive HBIM and how they would envision using it if it were available.

- Propose a root definition of HBIM.

1.4. Research Context and Previous Work

1.4.1. Research Context

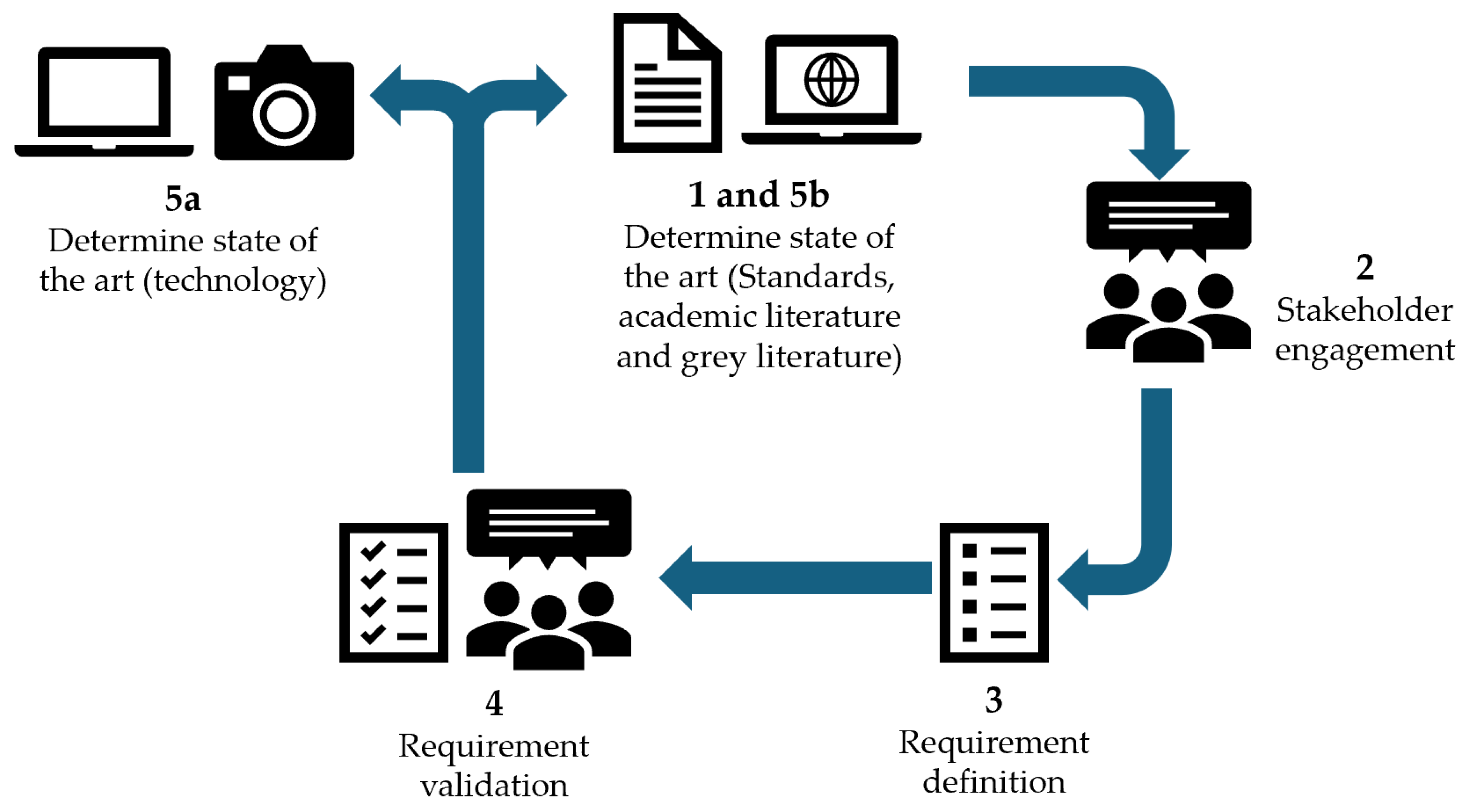

- This stage has two key activities. The first activity was a literature review of 178 articles on HBIM to determine the current state of the field [2]. The second activity involved reviewing academic literature, grey literature, and published standards to evaluate different ways of working with Cultural Heritage and to identify theoretical information requirements for HBIM [43,44]. Stage 1 of this study had an international scope. See Section 1.4.2 for more details.

- Stage 2 involves distributing a survey to members of the UK Heritage Community and evaluating their responses. The survey encompassed over two hundred questions and contained many free-form answers. Hence, the scope was intentionally limited to ensure the feasibility of analysing all responses with the limited resources available to the investigators.

- Stage 3 involves employing SE processes to define system requirements in response to the survey responses. This has been completed and will be detailed in Part 2 of this research.

- Stage 4 involves recirculating the proposed HBIM system requirements to other members of the Heritage Community. The intention is to broaden the scope of the research to an international context. This will help identify any region-specific variations or variations due to asset type. It will also gather perspectives that may have not been encompassed by Stage 2 of the research. The member feedback will be used to validate and adapt the proposed requirements as needed.

- The final stage of this study being undertaken by the authors will involve the comparison of the validated requirements with available technology (Stage 5a) and the existing standards and literature (Stage 5b). This will enable the authors to make recommendations as to how standards should be adapted for HBIM and how the proposed requirements can be achieved in practice.

1.4.2. Previous Work

2. Method

2.1. Participant Identification

2.2. Survey Reduction–Pilot Studies

2.3. Applying Systems Thinking

- Information about the participants of the survey, including their job areas and experience, the type of heritage they work with, and their previous experience with BIM (Section 3.1).

- Information regarding how data are currently managed within the Heritage Community (Section 3.2).

- Current working practices within the Heritage Community and organisational features that may impose constraints (Section 3.3).

- How participants perceive HBIM and how they would envision using it if it were available (Section 3.4).

- Customers: Those affected negatively or positively by T;

- Actors: Those carrying out T;

- Transformation process: Change from input to output;

- Weltanschauung (or worldview): The worldview and associated assumptions that provide context to T;

- Owners: Those responsible for making T happen or not;

- Environmental constraints: Elements outside the system that are “taken as given”.

3. The Problematic Situation

3.1. About the Participants

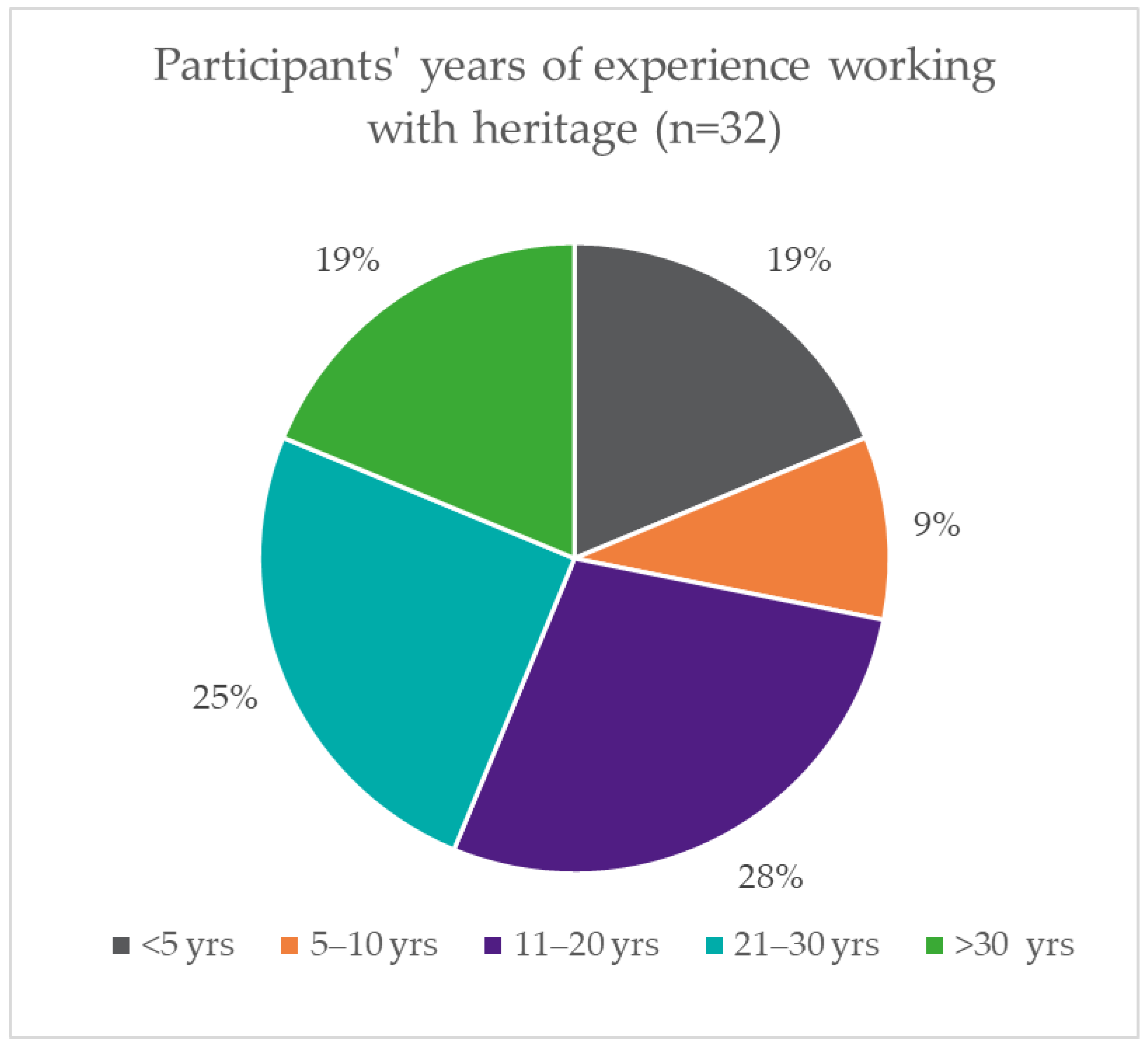

3.1.1. Experience and Expertise

3.1.2. Roles

- Heritage Management: This refers to individuals who are involved in the management and maintenance of heritage assets specifically.

- General Management: This refers to individuals who are involved in the management of a number of assets, which includes some heritage assets, or individuals who look after an asset because of the function it serves.

- AEC: This refers to individuals involved in the AEC industry. This incorporates both organisations specialising in heritage projects and organisations that typically deal with non-heritage assets.

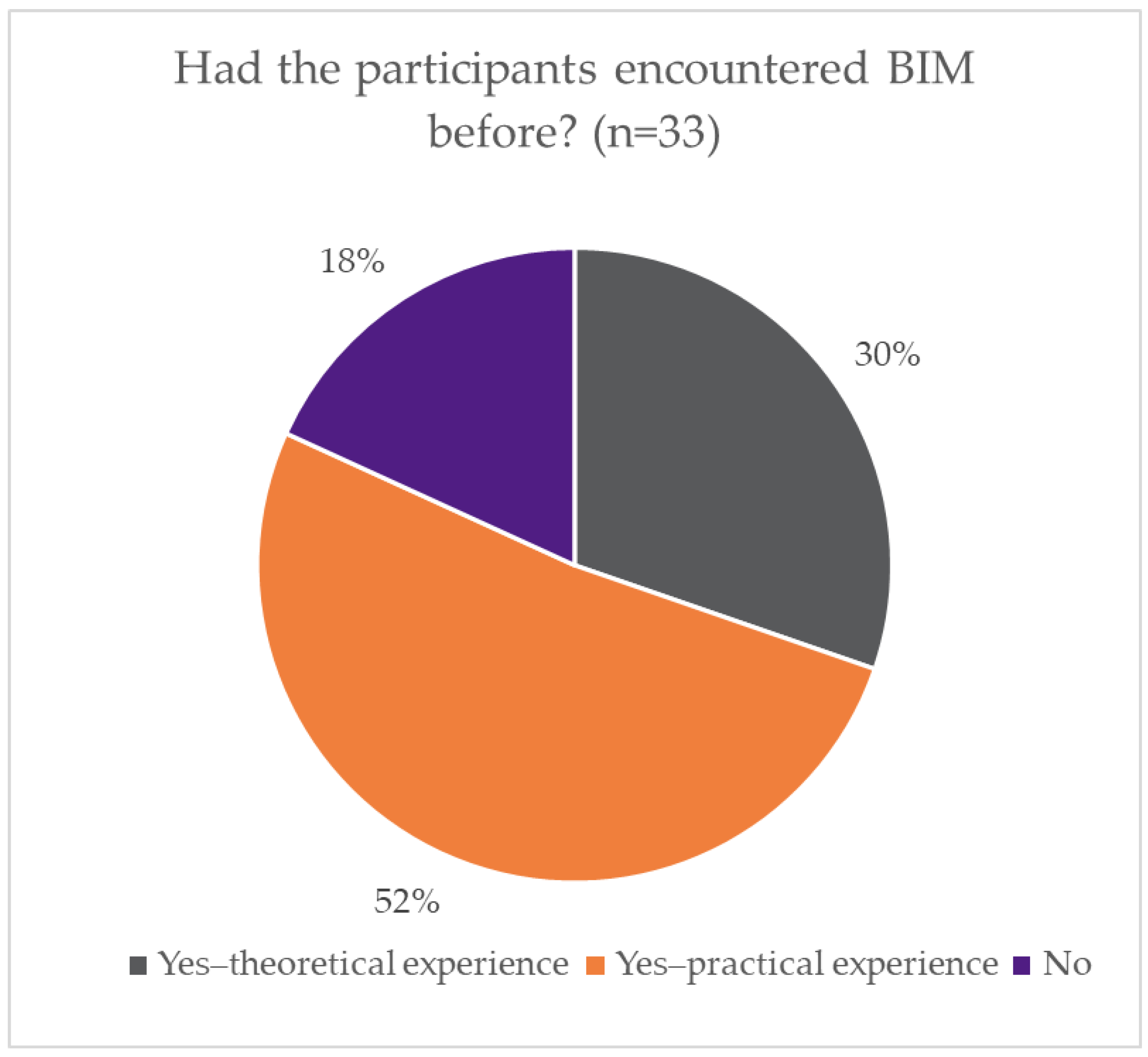

3.1.3. BIM Knowledge

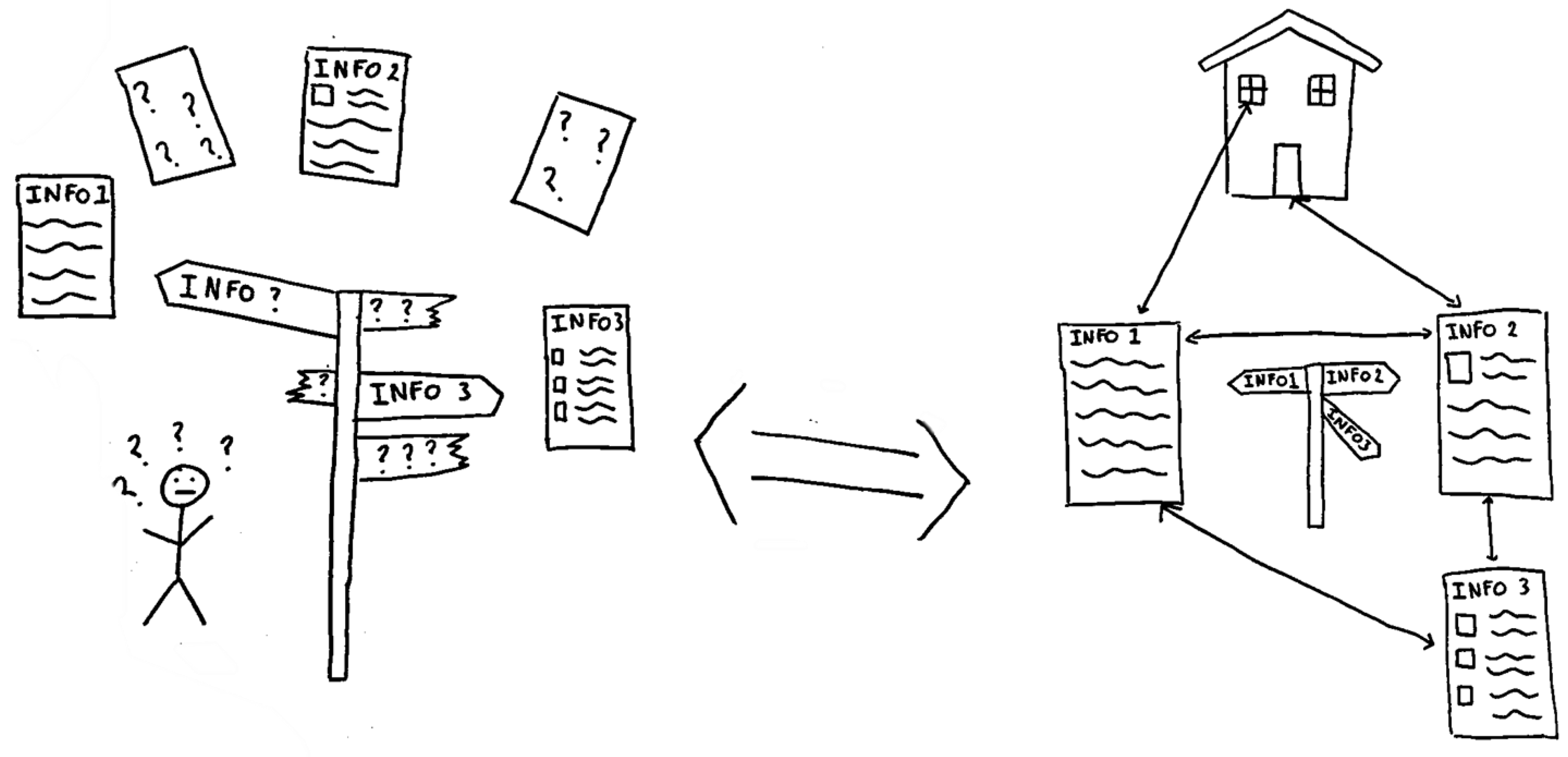

3.2. How Heritage Information Is Currently Managed

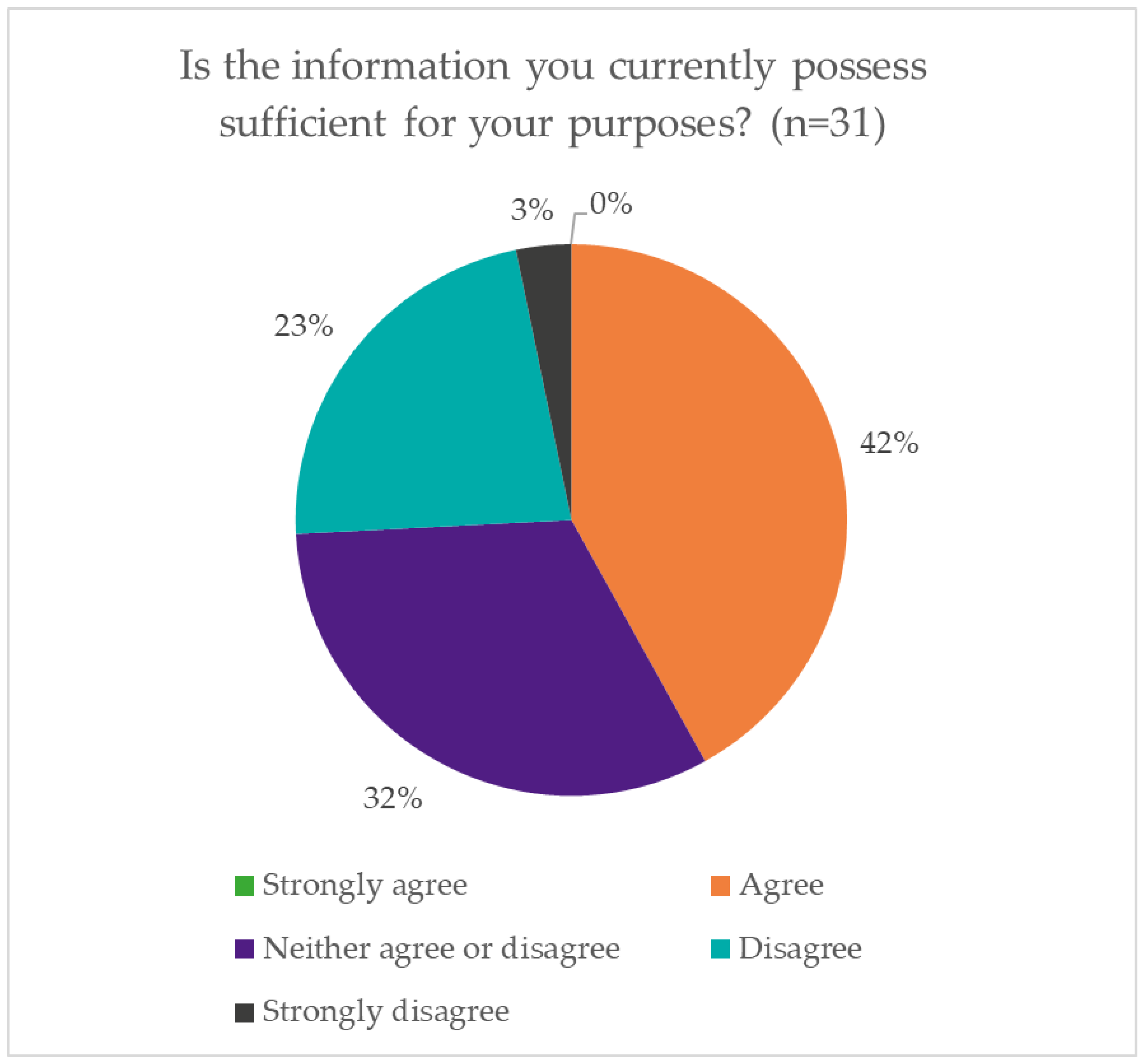

3.2.1. What Information Do Heritage Practitioners Possess?

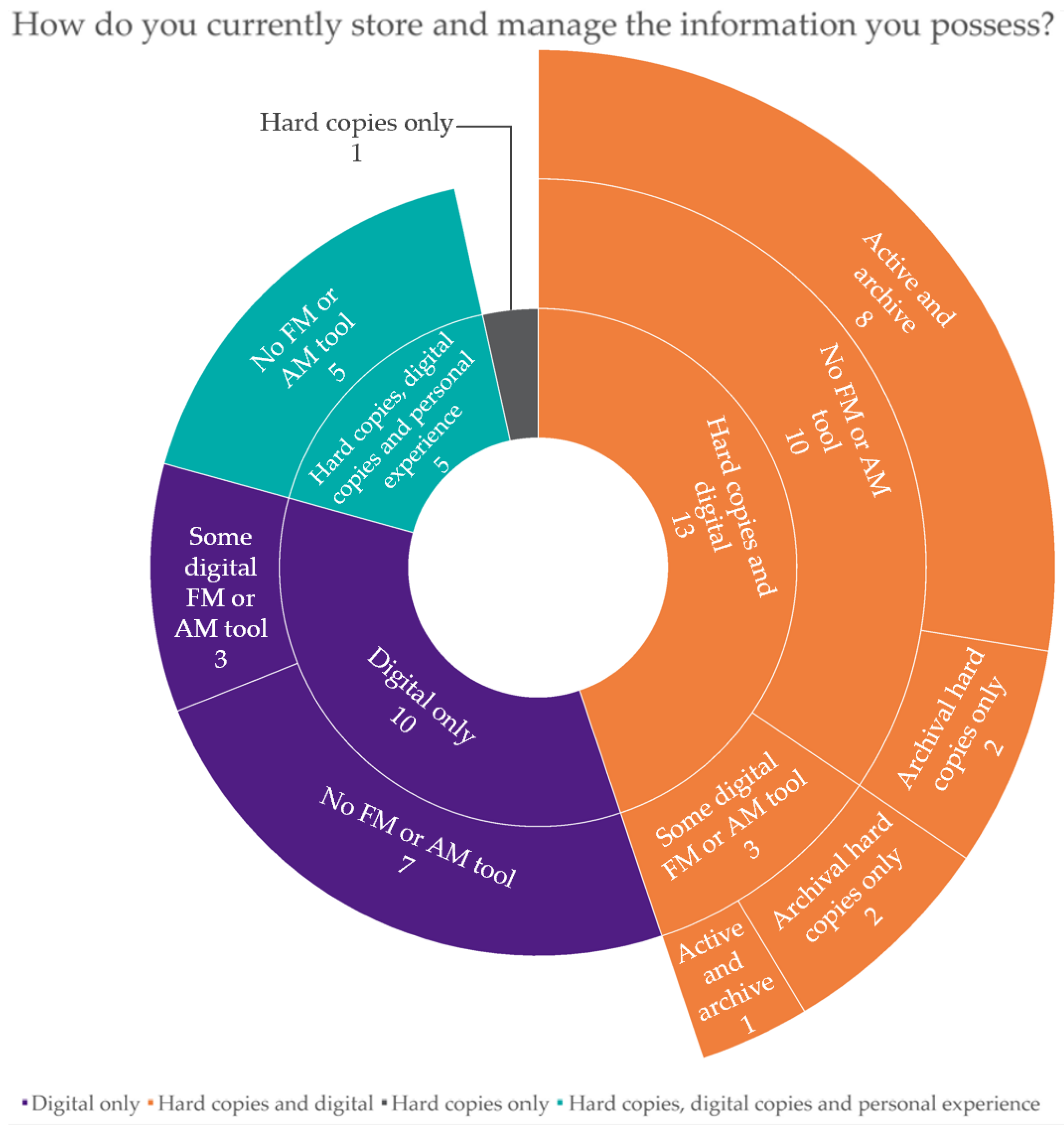

3.2.2. Evaluation of How Information Is Currently Stored and Managed

3.2.3. Types of Digital Tools Already in Use by the CH Sector

3.3. Working Constraints

3.3.1. Importance of Working Constraints

3.3.2. Accessibility of Assets

3.3.3. Working Locations

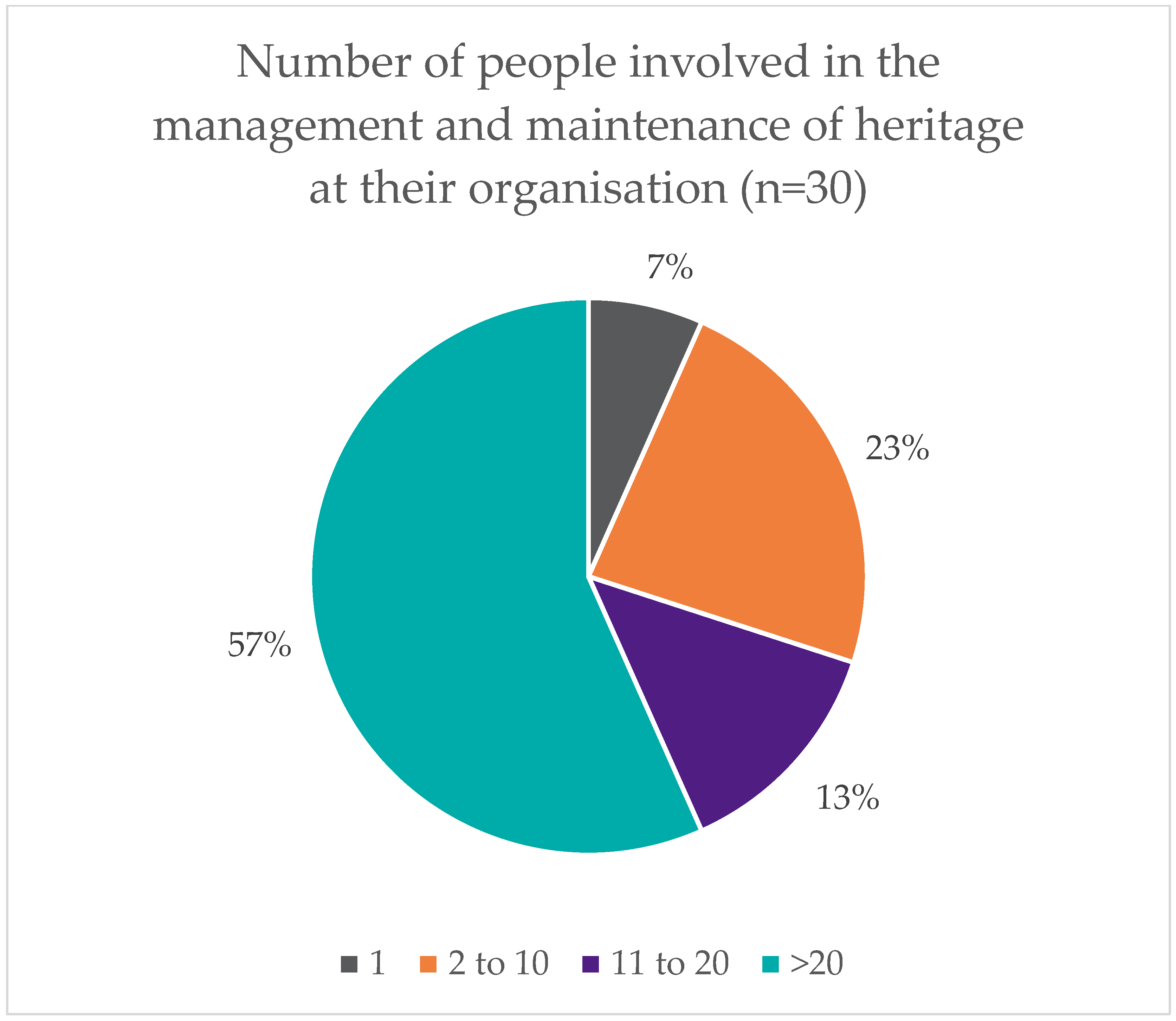

3.3.4. Organisation Size

3.3.5. Challenges of Working with Heritage

3.4. Uses of HBIM

3.4.1. Overview of Section

3.4.2. Proposed Use Cases

- Informing funding applications, planning, and design of new work/capital projects.

- Evaluating, planning, undertaking, and recording maintenance.

- Understanding the significance and/or function of an asset.

- Informing decisions.

- As a record, e.g., of asset condition or function, or of work undertaken.

- Planning activities.

- To share knowledge with others.

3.4.3. Participants’ Preferences

3.4.4. Renovation Projects

3.4.5. Restoration Projects

3.4.6. Conservation Projects

3.4.7. As a Virtual Tool Used to Share Heritage with the Public

3.4.8. Asset Management

3.4.9. Facilities Management

3.4.10. Translocation

3.4.11. Further Uses of HBIM

- Participant 17: “Client communication—the ability to abstract a BIM record and represent it to support a report in a simple way so that non-technical readers can get an idea of what’s being discussed”. They also suggested “linking the building archaeology”.

- Participant 18: “Integration with GIS tools for mapping and geospatial purposes. On a large site it is critical to be able to accurately report the location of assets. [It] would allow integrating topographical surveys with BIM models”. The participant was aware of some support for this in Free Open-Source Software (FOSS) but not in proprietary BIM tools.

- Participant 21: “Tracing the uses of a place over time. Different circulation routes, public facilities, how entrances and exits changed”.

- Participant 22: “If not already covered under previous headings, HBIM could be very valuable in monitoring & reporting of conditions over a continuous/protracted period of time”.

- Participant 26: HBIM could be used within the Metaverse.

- Participant 33: “Risk management, version control, design coordination, [Construction Design and Management] (CDM) Reg[ulation]s 2015, H&S file, ongoing asset management”.

3.4.12. Perceived Barriers to HBIM Implementation

4. Soft Systems Methodology for HBIM

- What: HBIM is a system that contains, in a structured and connected manner, all the information required for Heritage Management.

- Who: Members of the Heritage Community involved in the management and maintenance of Cultural Heritage.

- Why: The system makes information easy to locate to ensure informed management decisions.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEC | Architecture, Engineering, and Construction |

| AM | Asset Management |

| AR | Augmented reality |

| AV | Audio–Visual |

| BIM | Building Information Modelling |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CAFM | Computer-Aided Facilities Management |

| CCTV | Closed-Circuit Television |

| CDBB | Centre for Digital Built Britain |

| CDE | Common Data Environment |

| CDM | Construction Design and Management |

| CH | Cultural Heritage |

| CIOB | Chartered Institute of Building |

| CPD | Continuing Professional Development |

| EH | English Heritage |

| FM | Facilities Management |

| FOSS | Free Open-Source Software |

| GISs | Geographic Information Systems |

| H&S | Health and Safety |

| HBIM | Historic Building Information Modelling |

| HERs | Historic Environment Records |

| HRP | Historic Royal Palaces |

| INCOSE | International Council on Systems Engineering |

| LOD | Level of Detail |

| M&E | Mechanical and Electrical |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| NT | National Trust |

| O&M | Operation and Maintenance |

| RIBA | Royal Institute of British Architects |

| RICS | Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SE | Systems Engineering |

| SSM | Soft Systems Methodology |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| UN | United Nations |

| VR | Virtual reality |

References

- United Nations. 11: Make Cities and Human Settlements Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal11 (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Lovell, L.J.; Davies, R.J.; Hunt, D.V.L. The Application of Historic Building Information Modelling (HBIM) to Cultural Heritage: A Review. Heritage 2023, 6, 6691–6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; McGovern, E.; Pavia, S. Historic Building Information Modelling (HBIM). Struct. Surv. 2009, 27, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Grussenmeyer, P.; Koehl, M.; Macher, H.; Murtiyoso, A.; Landes, T. Review of Built Heritage Modelling: Integration of HBIM and Other Information Techniques. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 46, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Valldecabres, J.; Pellicer, E.; Jordan-Palomar, I. BIM Scientific Literature Review for Existing Buildings and a Theoretical Method: Proposal for Heritage Data Management Using HBIM. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2016: Old and New Construction Technologies Converge in Historic San Juan, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 31 May–2 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pocobelli, D.P.; Boehm, J.; Bryan, P.; Still, J.; Grau-Bové, J. BIM for Heritage Science: A Review. Herit. Sci. 2018, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, F.J.; Lerones, P.M.; Llamas, J.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J.; Zalama, E. A Review of Heritage Building Information Modeling (H-BIM). Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2018, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewart, I.J.; Zuecco, V. Heritage Building Information Modelling (HBIM): A Review of Published Case Studies. In Advances in Informatics and Computing in Civil and Construction Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Volk, R.; Stengel, J.; Schultmann, F. Building Information Modeling (BIM) for Existing Buildings—Literature Review and Future Needs. Autom. Constr. 2014, 38, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penjor, T.; Banihashemi, S.; Hajirasouli, A.; Golzad, H. Heritage Building Information Modeling (HBIM) for Heritage Conservation: Framework of Challenges, Gaps, and Existing Limitations of HBIM. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2024, 35, e00366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, B. Heritage Building Information Modelling (HBIM): A Review of Published Case Studies. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, XLVIII-1-2024, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P.; Holwell, S. Information, Systems and Information Systems: Making Sense of the Field; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- The Forum on Information Standards in Heritage (FISH). MIDAS Heritage—The UK Historic Environment Data Standard, v1.1; Historic England: Swindon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology Information System. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/information_system (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- The Royal Academy of Engineering. Creating Systems That Work: Principles of Engineering Systems for the 21st Century. 2007. Available online: https://raeng.org.uk/media/o3cnzjvw/rae_systems_report.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Bolton, A.; Butler, L.; Dabson, I.; Enzer, M.; Evans, M.; Fenemore, T.; Harradence, F.; Keaney, E.; Kemp, A.; Luck, A.; et al. Gemini Principles. 2018. Available online: https://www.cdbb.cam.ac.uk/DFTG/GeminiPrinciples#:~:text=The%20Gemini%20Principles%20report%20was,share%20data%20in%20the%20future (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- INCOSE UK Z5: Lean Systems Engineering. 2020. Available online: https://incoseuk.org/Documents/zGuides/Z5_Lean_rebrand_issue1.2_pdf_web.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Connor, D. Information System Specification & Design Roadmap; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (Faro Convention); Council of Europe: Faro, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- INCOSE, UK. Systems Thinking. Available online: https://incoseuk.org/Normal_Files/WhatIs/Systems_Thinking (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Gemini Council; Lamb, K. Gemini Papers: What Are Connected Digital Twins. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdbb.cam.ac.uk/files/gemini_papers_-_what_are_connected_digital_twins.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Centre for Digital Built Britain. About the Centre for Digital Built Britain. Available online: https://www.cdbb.cam.ac.uk/AboutCDBB (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Gemini Council; Lamb, K. Gemini Papers: How to Enable an Ecosystem of Connected Digital Twins. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdbb.cam.ac.uk/files/gemini_how.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Albert, M.-T.; Bernecker, R.; Cave, C.; Prodan, A.C.; Ripp, M. 50 Years World Heritage Convention: Shared Responsibility—Conflict & Reconciliation; Albert, M.-T., Bernecker, R., Cave, C., Prodan, A.C., Ripp, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-3-031-05659-8. [Google Scholar]

- Historic England Historic Environment Records (HERs). Available online: https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/technical-advice/information-management/hers/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Know Your Place About the Project. Available online: https://www.kypwest.org.uk/about-the-project/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Arches Arches for HERs. Available online: https://www.archesproject.org/arches-for-hers/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Floros, G.S.; Ellul, C. Loss of Information during Design & Construction for Highways Asset Management: A GeoBIM Perspective. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, VIII-4/W2-2021, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, N.; Ellul, C.; Re Cecconi, F.; Papapesios, N.; Dejaco, M.C. GeoBIM for Built Environment Condition Assessment Supporting Asset Management Decision Making. Autom. Constr. 2021, 130, 103859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, E.; de Ruvo, V.; Lingua, A.; Matrone, F.; Rizzo, G. HBIM-GIS Integration: From IFC to CityGML Standard for Damaged Cultural Heritage in a Multiscale 3D GIS. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrone, F.; Colucci, E.; De Ruvo, V.; Lingua, A.; Spanò, A. HBIM in a Semantic 3D GIS Database. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 42, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramage, M.; Shipp, K. Systems Thinkers; Springer: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-4471-7474-5. [Google Scholar]

- Checkland, P.; Scholes, J. Soft Systems Methodology in Action; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990; ISBN 0-471-92768-6. [Google Scholar]

- INCOSE Systems and SE Definitions. Available online: https://www.incose.org/about-systems-engineering/system-and-se-definitions (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Checkland, P.B. The systems movement and the “failure” of management science. Cybern. Syst. 1980, 11, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P. Systems Thinking, Systems Practice: Includes a 30-Year Retrospective; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-471-98606-5. [Google Scholar]

- INCOSE. INCOSE Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Checkland, P.; Poulter, J. Learning for Action: A Short Definitive Account of Soft Systems Methodology, and Its Use for Practitioner, Teachers and Students; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Checkland, P. From Optimizing to Learning: A Development of Systems Thinking for the 1990s. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1985, 36, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Foreman, G.; Sattineni, A.; Li, B. Integrating Stakeholders’ Priorities into Level of Development Supplemental Guidelines for HBIM Implementation. Buildings 2023, 13, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 19650-3:2018; Organization and Digitization of Information about Buildings and Civil Engineering Works, Including Building Information Modelling (BIM). Information Management Using Building Information Modelling. Operational Phase of the Assets. The British Standards Institute: London, UK, 2018.

- Global Forum on Maintenance and Asset Management. The Asset Management Landscape, 2nd ed.; Global Forum on Maintenance and Asset Management, 2014; Available online: https://gfmam.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/GFMAMLandscape_SecondEdition_English.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Lovell, L.J.; Davies, R.J.; Hunt, D.V.L. Building Information Modelling Facility Management (BIM-FM). Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, L.; Davies, R.J.; Hunt, D.V.L. Theoretical Information Requirements for Historic Building Information Modelling. In Proceedings of the FCIC’24 Faro Convention International Conference, Porto, Portugal, 29 January 2024. in publication. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball Sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 1961, 32, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS ISO 55000:2014; Asset Management. Overview, Principles and Terminology. The International Standards Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Historic England. Practical Building Conservation: Conservation Basics; Martin, B., Wood, C., McCaig, I., Eds.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2024; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, D.; Barter, M.; Shepherd, A.; Joynt, A. RIBA Conservation Guide, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2024; ISBN 9781914124877. [Google Scholar]

- Heesom, D.; Boden, P.; Hatfield, A.; De Los Santos Melo, A.; Czarska-Chukwurah, F. Implementing a HBIM Approach to Manage the Translocation of Heritage Buildings. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 2948–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, E.F. Rich Pictures: A Visual Method for Sensemaking Amid Complexity. Am. J. Eval. 2024, 45, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Open University Rich Pictures. Available online: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/science-maths-technology/engineering-technology/rich-pictures (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- ISO 41011:2017(En); Facility Management—Vocabulary. The International Standards Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 5th ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2000; ISBN 0-415-19541-1. [Google Scholar]

- RIBA. RIBA Plan of Work 2020 Overview; RIBA: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rathnasiri, P.; Jayasena, S. Green Building Information Modelling Technology Adoption for Existing Buildings in Sri Lanka. Facilities Management Perspective. Intell. Build. Int. 2022, 14, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, M.; Motamedi, A.; Guénette, L.M.; Forgues, D. Analysis of BIM Use for Asset Management in Three Public Organizations in Québec, Canada. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2019, 9, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government Data Quality Hub. Hidden Costs of Poor Data Quality. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/hidden-costs-of-poor-data-quality (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Haug, A.; Zachariassen, F.; Liempd, D. van The Costs of Poor Data Quality. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2011, 4, 168–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPartland, R. What Is the Common Data Environment (CDE)? Available online: https://www.thenbs.com/knowledge/what-is-the-common-data-environment-cde#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20a%20project%20might,out%20in%20Employer’s%20Information%20Requirements (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- UNESCO; ICCROM; ICOMOS. IUCN Enhancing Our Heritage Toolkit 2.0: Assessing Management Effectiveness of World Heritage Properties and Other Heritage Places. 2023. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/eoh20/ (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Mayouf, M.; Jones, J.; Elghaish, F.; Emam, H.; Ekanayake, E.M.A.C.; Ashayeri, I. Revolutionising the 4D BIM Process to Support Scheduling Requirements in Modular Construction. Sustainability 2024, 16, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boton, C. Supporting Constructability Analysis Meetings with Immersive Virtual Reality-Based Collaborative BIM 4D Simulation. Autom. Constr. 2018, 96, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Cong, W. Remote Practice Methods of Survey Education for HBIM in the Post-Pandemic Era: Case Study of Kuiwen Pavilion in the Temple of Confucius (Qufu, China). Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, E.S.; García-Valldecabres, J.; Blasco, M.J.V. The Use of HBIM Models as a Tool for Dissemination and Public Use Management of Historical Architecture: A Review. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2018, 13, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, A.; Fiorini, L.; Massaro, R.; Santoni, C.; Tucci, G. HBIM for the Preservation of a Historic Infrastructure: The Carlo III Bridge of the Carolino Aqueduct. Appl. Geomat. 2022, 14, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.M.; Mou, C.C.; Lu, Y.C.; Yen, Y.N. HBIM in Cultural Heritage Conservation: Component Library for Woodwork in Historic Buildings in Taiwan. In Digital Heritage. Progress in Cultural Heritage: Documentation, Preservation, and Protection; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11196. [Google Scholar]

- English Heritage. Sustainable Conservation Principles; English Heritage: Swindon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Conservation of Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://uis.unesco.org/en/glossary-term/conservation-cultural-heritage (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Kołakowski, T. Translocation of Historic Monuments as an Economic Project. J. Interdiscip. Res. 2016, 5, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Autodesk. Revolutionizing Facility Management for a Historic Educational Institution with Digital Twins. Available online: https://intandem.autodesk.com/resource/february-2024-webinar/?mktvar002=6254648004%7CEML%7C775937782&utm_medium=email&utm_source=follow-up&utm_campaign=6254648operationalfy-24-q4-tandem-product-update-webinar-january&utm_id=6254648004&mkt_tok=OTE4LUZPRC00MzMAAAGRQfiXpAMgGCZz9pIjZQAtB7dgl44iwfGr9y3cz9hPGpOlfrYpEf-0_7mgiDiakJOm2een7X0CZWApJInyagKQSMi12gZ9-de-pVp7bBCl6ETocxFBf_BH#recording (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Boesgaard, C.; Hansen, B.V.; Kejser, U.B.; Mollerup, S.H.; Ryhl-Svendsen, M.; Torp-Smith, N. Prediction of the Indoor Climate in Cultural Heritage Buildings through Machine Learning: First Results from Two Field Tests. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudbury Gasworks Restoration Trust. The Gasworks in 3D. Available online: https://sudburygasworks.com/2023/01/19/the-gasworks-in-3d/ (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Akcamete, A.; Akinci, B.; Garrett, J.H. Potential Utilization of Building Information Models for Planning Maintenance Activities. In Proceedings of the EG-ICE 2010—17th International Workshop on Intelligent Computing in Engineering, Nottingham, UK, 30 June–2 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tsay, G.S.; Staub-French, S.; Poirier, É. BIM for Facilities Management: An Investigation into the Asset Information Delivery Process and the Associated Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarneh, S.; Danso-Amoako, M.; Al-Bizri, S.; Gaterell, M.; Matarneh, R. BIM-Based Facilities Information: Streamlining the Information Exchange Process. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2019, 17, 1304–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currà, E.; D’amico, A.; Angelosanti, M. HBIM between Antiquity and Industrial Archaeology: Former Segrè Papermill and Sanctuary of Hercules in Tivoli. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Giordano, A.; Sang, K. From site survey to HBIM model for the documentation of historic buildings: The case study of Hexinwu Village in China. Conserv. Sci. Cult. Herit. 2020, 20, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ermenyi, T.; Enegbuma, W.I.; Isaacs, N.; Potangaroa, R. Building Information Modelling Workflow for Heritage Maintenance. In Proceedings of the International Conference of the Architectural Science Association, Auckland, New Zealand, 26–27 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barrile, V.; Fotia, A. A Proposal of a 3D Segmentation Tool for HBIM Management. Appl. Geomat. 2022, 14, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffino, P.A.; Permadi, D.; Gandino, E.; Haron, A.; Osello, A.; Wong, C.O. Digital Technologies for Inclusive Cultural Heritage: The Case Study of Serralunga d’alba Castle. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 4, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, F.; Bolognesi, C.M.; Bonini, J.A.; Mandelli, A. The Virtual Historical Reconstruction of the Cerchia Dei Navigli of Milan: From Historical Archives, 3D Survey and HBIM to the Virtual Visual Storytelling. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, 46, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspari, F.; Barbieri, F.; Fascia, R.; Ioli, F.; Pinto, L. An Open-Source Web Platform for 3D Documentation and Storytelling of Hidden Cultural Heritage. Heritage 2024, 7, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 30173:2023; Digital Twin—Concepts and Terminology. The International Standards Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Health and Safety Executive. Managing Health and Safety in Construction Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2015; Health and Safety Executive: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Salzano, A.; Cascone, S.; Zitiello, E.P.; Nicolella, M. Construction Safety and Efficiency: Integrating Building Information Modeling into Risk Management and Project Execution. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Obstfeld, D. Organizing and the Process of Sensemaking. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Information Category | Information Requirement |

|---|---|

| Geometric surveys: This is defined as the geometric information gathered with which to create the model. These data will typically be provided by techniques such as photogrammetry or laser scanning. These techniques produce point clouds, which are a collection of thousands of points that provide a 3D representation of an area. | The geometric survey |

| Details about the geometric survey, e.g., method and who carried it out | |

| Information (data) about the fabric of the asset: This is defined as the physical material/structure that makes up the asset. | Material data, e.g., what materials are used |

| Architectural data, e.g., floor plans | |

| Current building fabric status data | |

| Condition assessments: This is defined as inspections of the physical condition of an asset, which can include, but are not limited to, assessments of decay or energy performance. | The raw data from the assessment |

| The results and recommendations of the assessments | |

| Details about the assessments, e.g., method and who carried it out | |

| Legal requirements: This is defined as any requirement that may affect your ability to carry out certain work. This may include a planning regulation (e.g., Grade Listing, etc.) or statutory document (e.g., other requirements such as conditions of bequest). | Planning regulations |

| Statutory documents affecting the asset | |

| Historical information: This is defined as archaeological data (including data about lost heritage) and major changes to an asset (not regular conservation work) over time. It does not refer to historical significance. | Archaeological evidence |

| Changes that have occurred over time | |

| Environment data: This is defined as more detailed data about the specific environment (or space) of an asset, which may affect its condition or performance. This may be at a large scale (e.g., a whole building) or a smaller scale (e.g., light levels in a specific room affect a specific object). | Light levels (internal and external) |

| Vibration levels | |

| Weather | |

| Dust levels | |

| Humidity | |

| Safety and security information: This is defined as any information related to the safety and security of the asset. This could include fire evacuation drawings, locations of fire alarms, and accessibility information such as wheelchair-accessible routes. | Fire safety |

| Health and Safety (H&S) | |

| Potential threats/risks and vulnerabilities | |

| Security | |

| Accessibility information | |

| Space data: This is defined as information about how the physical space of an asset is broken down and used. This may include, but is not limited to, room allocations (space breakdown), which areas are open to the public/private (space usage), occupancy limits, average footfall (visitor information), etc. | Space usage |

| Space breakdown | |

| Visitor information | |

| Maintenance manuals/instructions: This is defined as information provided or required to help plan and/or carry out maintenance and conservation work on an object. | Required equipment |

| Minimum level of performance | |

| Whether the maintenance can be performed by a normal user or requires skilled personnel | |

| Intervention type (work required) | |

| Intervention frequency | |

| Previous maintenance including conservation history | |

| Historical significance: This is defined as the tangible or intangible significance attributed to the importance of the asset, e.g., how it evidences a way of life/practice, architectural or structural importance, associations to notable figures, etc. | For education |

| To inform management decisions | |

| Location data: This is defined as information about the wider location surrounding the asset. This may or may not be owned by you. For example, a local river may be prone to flooding and a risk to your asset. Alternatively, it may be information about the grounds surrounding the asset itself, e.g., the boundaries of the land. | Setting of the asset (e.g., grounds) |

| Nearby physical hazards | |

| Related assets nearby | |

| Other generic locational information | |

| Objects not part of the building’s fabric: This is defined as important objects not necessarily considered part of the building, which could be artistic (e.g., tapestries, artwork, sculptures, etc.) or other moveable assets (e.g., old factory machinery, furniture with a specific significance, etc.). | Moveable objects |

| Artistic objects |

| Participant ID | Job Title | Organisation | Job Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Museum Manager | […] | GM |

| 2 | Carbon and Sustainability Manager | University of Birmingham | GM |

| 3 | Contracts Manager | […] | AEC |

| 4 | Operational Programme Manager | […] | GM |

| 5 | Site Engineer | […] | AEC |

| 6 | Head of Service—NDSU | BCC [Birmingham City Council] | GM |

| 7 | Data Manager | University of Birmingham | GM |

| 8 | Head of Historic Buildings | Historic Royal Palaces | HM |

| 9 | Committee Member and Trustee | The Moseley Society | HM |

| 10 | Facilities Manager (Head of Facilities and Asset Management Department) | Birmingham Museums Trust | HM |

| 11 | Assistant Building Surveyor | National Trust | HM |

| 12 | Collections and House Officer | National Trust | HM |

| 13 | […] | […] | HM |

| 14 | Head of BIM and Digital Assets | University of Birmingham Estates | GM |

| 15 | Senior Building Surveyor | […] | HM |

| 16 | […] | […] | HM |

| 17 | Secretary | Romsey & District Buildings Preservation Trust | HM |

| 18 | […] | […] | HM |

| 19 | Project Development Manager | […] | HM |

| 20 | Project Manager Conserving the Historic Estate | […] | HM |

| 21 | Author and Editor | […] | HM |

| 22 | […] | […] | HM |

| 23 | […] | […] | AEC |

| 24 | Archaeological Illustrator | […] | HM |

| 25 | Architect (Director) | Rodney Melville & Partners | AEC |

| 26 | HBIM Coordinator | […] | AEC |

| 27 | […] | […] | AEC |

| 28 | Engineer | […] | AEC |

| 29 | CEO | Heritage Lincolnshire | HM |

| 30 | Head of Infrastructure | Severn Valley Railway | HM |

| 31 | Chief Executive | Portsmouth Naval Base Property Trust | HM |

| 32 | Infrastructure Manager | Gloucestershire Warwickshire Steam Railway | HM |

| 33 | Head of Building Conservation | English Heritage | HM |

| Theoretical Information Category | Information Already Possessed by the Survey Participants |

|---|---|

| Geometric surveys: This is defined as the geometric information gathered with which to create the model. These data are typically provided by techniques such as photogrammetry or laser scanning. These techniques produce point clouds, which are a collection of thousands of points that provide a 3D representation of an area. | Laser scans (explicitly specified) and other 3D scans (exact type unspecified by participants) Measured surveys |

| Information (data) about the fabric of the asset: This is defined as the physical material/structure that makes up the asset. | Architectural drawings (new and historic) including plans, layouts, and elevations Unspecified drawings (new and historic) Information about the materials Conservation and architectural reports Information about historic architectural families Drain surveys Descriptive documents Mechanical and Electrical installation surveys |

| Condition assessments: This is defined as inspections of the physical condition of an asset, which could include, but are not limited to, assessments of decay or energy performance. | Various surveys, e.g., building, environmental, asbestos, timber, structural, plaster, mechanical, and electrical Condition surveys/reports (historic and new) Results from visual inspections Consultant reports |

| Legal requirements: This is defined as any requirement that may affect your ability to carry out certain work. This may include a planning regulation (e.g., Grade Listing, etc.) or statutory document (e.g., other requirements such as conditions of bequest). | Previous planning applications Documents supporting previous planning processes Legal records Compliance records, e.g., asbestos |

| Historical information: This is defined as archaeological data (including data about lost heritage) and major changes to an asset (not regular conservation work) over time. It does not refer to historical significance. | Record/assumptions of the building’s use over time Record/assumptions of the building’s form/any changes over time Information about former capital projects [it is assumed here that a capital project involves some kind of major change] Archaeological reports/surveys/collections |

| Environment data: This is defined as more detailed data about the specific environment (or space) of an asset that may affect its condition or performance. This may be at a large scale (e.g., a whole building) or a smaller scale (e.g., light levels in a specific room affect a specific object). | Environmental parameters affecting integrity |

| Safety and security information: This is defined as any information related to the safety and security of the asset. This could include fire evacuation drawings, locations of fire alarms, and accessibility information such as wheelchair-accessible routes. | Health impact assessments |

| Space data: This is defined as information about how the physical space of an asset is broken down and used. This may include, but is not limited to, room allocations (space breakdown), which areas are open to the public/private (space usage), occupancy limits, average footfall (visitor information), etc. | - [No information types given] |

| Maintenance manuals/instructions: This is defined as information provided or required to help plan and/or carry out maintenance and conservation work on an object. | Records of previous maintenance work (cyclical and reactive) Records of previous conservation work Records of statutory testing Building maintenance plans Service plans Historic operation and maintenance plans Standard operating sheets Working documents for heating, lighting, Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV), and Audio–Visual (AV) systems Information about cleaning |

| Historical significance: This is defined as the tangible or intangible significance attributed to the importance of the asset, e.g., how it evidences a way of life/practice, architectural or structural importance, associations to notable figures, etc. | Reports/research on asset history and significance Historical background Architectural heritage surveys Archival sources regarding the holding’s provenance Secondary sources relating to the asset history Original accounts from the asset’s construction Building gazetteers |

| Location data: This is defined as information about the wider location surrounding the asset. This may or may not be owned by you. For example, a local river may be prone to flooding and a risk to your asset. Alternatively, it may be information about the grounds surrounding the asset itself, e.g., the boundaries of the land. | Maps Topographic surveys Site level drawings |

| Objects not part of the building’s fabric: This is defined as important objects not necessarily considered part of the building, which could be artistic (e.g., tapestries, artwork, sculptures, etc.) or other moveable assets (e.g., old factory machinery, furniture with a specific significance, etc.). | Asset registers |

| New Information Category | Information Type Already Possessed by the Survey Participants |

|---|---|

| Visual depictions: This is defined as images, drawings, or surveys that provide a visual representation of all or part of an asset. | Matterport data Drone surveys (Note: whilst both drone surveys and Matterport surveys can provide geometric data, the exact drone survey was not specified. Furthermore, Matterport surveys are not typically used for geometric data, instead, they are typically used to create virtual tours [40]. The authors are aware of one participant who only uses Matterport scans for its virtual tour capability and it is possible to undertake a Matterport survey without collecting geometric data, hence the inclusion within this category. Photographs and paintings (historic and current). |

| Management plans/policies: This is defined as documents recording or dictating the strategic management objectives of an asset. | Management data and records Conservation policies Conservation management plans |

| Project files for proposed and/or previous capital work: This is defined as information created or required as part of the conception and design stages of a capital project (assumed to correspond with suggested information exchanges for RIBA stages 0–4 [54]). | Schedule of work Feasibility studies Company minutes and correspondence Specification of work Business plans Intended design plans from architects |

| Other | Detailed BIM models Historical/archival records (unspecified) Other reports (unspecified) Consultants’ reports (unspecified) |

| Challenge of Working with Heritage | Details | Participant No. |

|---|---|---|

| Money | Over 65% of the participants cited money-related challenges. This challenge encompassed a lack of available funds, lack of available resources, high cost of materials and labour, and difficulty accessing external funds or fundraising. | 1, 4, 6, 8, 10–11, 13–22, 24, 29–33 |

| Availability of skilled labour | Participants mentioned a growing lack of heritage skills or difficulty finding contractors with appropriate expertise. | 3, 8, 13, 17, 20, 22, 26, 29–31 |

| Planning/legislative/listing constraints | Participants talked about extra constraints imposed by having to comply with heritage protections or satisfy external heritage stakeholders (e.g., conservation officers). This also limited the scope of any interventions and increased the time to gain planning consent. | 2, 4, 6, 9, 11, 17, 19, 24 |

| Historic materials | Challenges regarding the materials in use. This included trying to stop the further degradation of materials reaching their end of life, the ingress of plant life, and a lack of homogeneity in material properties. | 3, 12, 19–20, 28, 31 |

| Client aspirations and expectations | This included disparity between the “purest vision and the practical vision” (Participant 6) as well as a limited understanding of the legislative implications of heritage significance. | 6, 14, 23, 25 |

| Climate change | Climate change or impacts of climate change, e.g., increased flooding. | 8, 22, 31 |

| Access requirements | Both gaining access as a worker and allowing access for the public. | 12, 20, 24 |

| Insufficient time | Insufficient time to plan work, carry out activities, apply for funding, etc. | 1, 10, 24 |

| Insufficient staff | Insufficient staff to plan work, carry out activities, apply for funding, etc. | 1, 4, 10 |

| Access to historical records/information | Limited access to historical information for planning future interventions or informing activities. | 5, 17–18 |

| Limited long-term sustainability | A general lack of long-term sustainability including a lack of forward planning within organisations. | 20, 22 |

| Public perception | The impact of public perception (see Section 3.3.2). | 24 |

| Potential Use of HBIM | Definition |

|---|---|

| Renovation projects | Defined as work to upgrade or change an asset. This could be for aesthetic, structural, or energy performance reasons. |

| Restoration projects | Defined as any work attempting to return an asset to its original condition. |

| Conservation projects | Defined as actions/work to maintain an asset in its current condition. This includes day-to-day and ad hoc maintenance. |

| As a virtual tool used to share heritage with the public | This is envisioned as an educational tool (potentially incorporating AR/VR) that could contain information about the intangible heritage of the asset or be used to teach others about conservation, etc. |

| Asset Management | Defined as managing an asset at an organisational level to maintain its value in line with organisational objectives. |

| Facilities Management | Defined as managing the asset and its contents for day-to-day running. This involves planning maintenance, managing resources, space management, and monitoring energy performance. |

| Translocation | Defined as moving a structure from one location to another. It may be intact for the relocation; dismantled from its original site and rebuilt somewhere else; or it may be recreated from already dismantled parts at a new location. |

| Challenge [of Implementing HBIM] | Detail | Participant No. |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | Participants mentioned challenges regarding the cost of HBIM implementation, staff training, and ongoing use. | 4, 5, 8, 10, 13, 17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 26, 33 |

| Encouraging uptake | Participants believed it would be difficult to convince others in their organisation, clients, or external stakeholders to utilise HBIM. | 14, 17, 18, 29, 32 |

| Upskilling and training users/creators | Participants thought training people to use HBIM or have the skills to implement it would be a challenge. | 5, 6, 8, 23, 27 |

| Keeping the system in use and up to date | Participants envisaged challenges ensuring any HBIM system was continuously used and updated. | 5, 10, 16, 21, 24 |

| Time/effort/resource required to implement HBIM | Some participants believed the time taken to implement HBIM was not feasible with their available time and resources. | 10, 17, 23, 30, 31 |

| Making the user interface uncomplicated and more compelling than existing tools | Participants perceived challenges in making large amounts of data easily understandable and presenting it better than existing tools. | 1, 2, 19, 28 |

| Available software/hardware | Participants thought they had insufficient existing hardware/software or that it would be a challenge to gain sufficient hardware/software. | 12, 23, 29 |

| Ensuring robust quality control procedures are in place | Participants mentioned there would be a need to/or there would be difficulty in implementing quality control procedures | 11, 24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lovell, L.J.; Davies, R.J.; Hunt, D.V.L. A Systems Thinking Approach to the Development of HBIM: Part 1—The Problematic Situation. Heritage 2025, 8, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8010021

Lovell LJ, Davies RJ, Hunt DVL. A Systems Thinking Approach to the Development of HBIM: Part 1—The Problematic Situation. Heritage. 2025; 8(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleLovell, Lucy J., Richard J. Davies, and Dexter V. L. Hunt. 2025. "A Systems Thinking Approach to the Development of HBIM: Part 1—The Problematic Situation" Heritage 8, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8010021

APA StyleLovell, L. J., Davies, R. J., & Hunt, D. V. L. (2025). A Systems Thinking Approach to the Development of HBIM: Part 1—The Problematic Situation. Heritage, 8(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8010021