Types and Effectiveness of Public Policy Measures Combatting Graffiti Vandalism at Heritage Sites

Abstract

1. Introduction

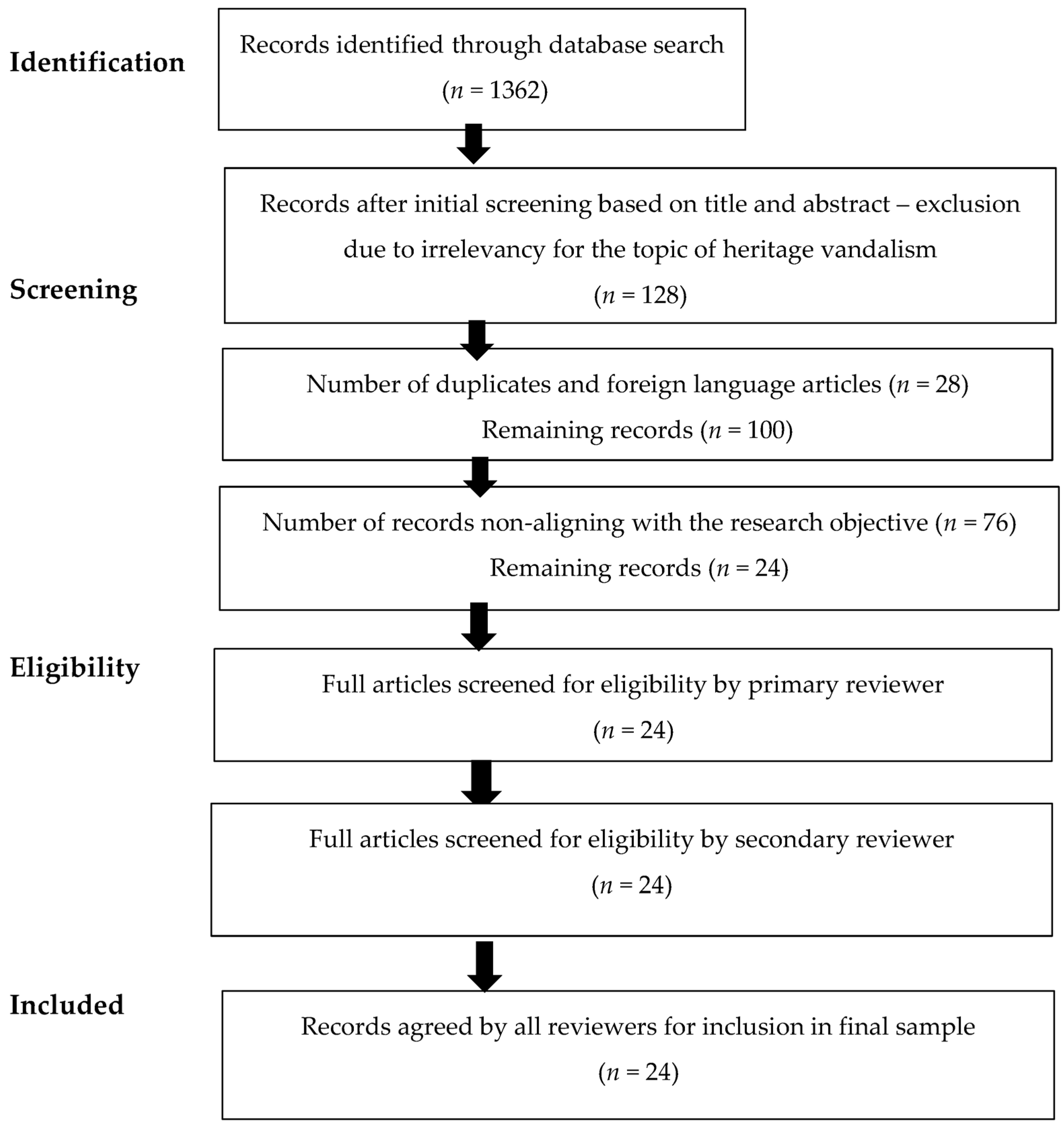

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

- Proactive measures: Legislation, Education and Public Awareness Raising, Data Gathering and Monitoring, Heritage Management, Legal Art Sites;

- Reactive measures: Criminal Sanctions, Graffiti Removal, and Damage Repair.

3.1. Proactive Measures and Policies

3.1.1. Legislation

3.1.2. Education and Public Awareness Raising

3.1.3. Data Gathering

3.1.4. Heritage Management

3.1.5. Legal Art Sites as a Proactive Measure

3.2. Reactive Measures

3.2.1. Criminal Sanctions

3.2.2. Graffiti Removal and Damage Repair

4. Good Practice Examples

4.1. New York

4.2. Toronto

4.3. Stockholm

4.4. Bogotá

4.5. Bunbury

4.6. Wellington

4.7. Melbourne

4.8. Barcelona

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Definition of GRAFFITI. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/graffiti (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Merrill, S. Keeping it real? Subcultural graffiti, street art, heritage and authenticity. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.; Offler, N.; Hirsch, L.; Every, D.; Thomas, M.J.; Dawson, D. From broken windows to a renovated research agenda: A review of the literature on vandalism and graffiti in the rail industry. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2012, 46, 1280–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://uis.unesco.org/en/glossary-term/cultural-heritage (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Donnell, N.; Anderson, T. Zagreb Visitor Survey 2017/18. 2018. Available online: https://www.infozagreb.hr/documents/b2b/STRZagrebVisitorSurvey.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Reducing Graffiti Vandalism|The NSMC. Available online: https://www.thensmc.com/resources/showcase/reducing-graffiti-vandalism (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- The Cost and Impact of Graffiti Removal in the UK—See Brilliance Blog. Available online: https://www.seebrilliance.com/vandalism-or-art-the-cost-and-impact-of-graffiti-removal-in-the-uk/ (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Eser, A. Graffiti Statistics: Insights into the Multibillion-Dollar Global Street Art Market. 2024. worldmetrics.org. Available online: https://worldmetrics.org/graffiti-statistics/ (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- GraffitiResistance_050615.pdf. Available online: https://www.alpolic-americas.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/GraffitiResistance_050615.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- GraffitiVandalismAuditReport-WebVersion.pdf. Available online: https://www.edmonton.ca/sites/default/files/public-files/documents/GraffitiVandalismAuditReport-WebVersion.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marche, G. Local democracy and public spaces in contest: Graffiti in San Francisco. In Democracy, Participation and Contestation; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, J.I. How major urban centers in the United States respond to graffiti/street art. In Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grove, L. Heritocide? Defining and Exploring Heritage Crime. Public Archaeol. 2013, 12, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, A.M.D.; Iyer, A.; Yates, D. Heritage and Criminal Sanctions. In The Routledge Handbook of Heritage and the Law, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criminal Offences Against Cultural Heritage Within the Italian Legal Framework After Law 9 March 2022, n. 22. Available online: https://publicatt.unicatt.it/retrieve/25071be3-4000-4e62-bb7e-a0eaa63f4424/CulturalHeritageCriminalLaw_Italy_2022%285%29.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- AlMasri, R.; Ababneh, A. Heritage Management: Analytical Study of Tourism Impacts on the Archaeological Site of Umm Qais—Jordan. Heritage 2021, 4, 2449–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chylińska, D.; Kosmala, G. The ‘I was here’ syndrome in tourism: The case of Poland. Quaest. Geogr. 2023, 42, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.H.; Al-Rousan, R.M.; Bala’awi, F.A. They Were Here: Graffiti by Tourists in the Ancient City of Jerash, Jordan. J. East. Mediterr. Archaeol. Herit. Stud. 2022, 10, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A. Negotiated consent or zero tolerance? Responding to graffiti and street art in Melbourne. City 2010, 14, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, H.; Bires, Z.; Berhanu, K. Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: Evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, S.O.C. Graffiti at Heritage Places: Vandalism as Cultural Significance or Conservation Sacrilege? Time Mind 2011, 4, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronela, S.-U.; Sandu, I.; Stratulat, L. The conscious deterioration and degradation of the cultural heritage. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2017, 8, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzigiannis, D. Vandalism of Cultural Heritage: Thoughts Preceding Conservation Interventions. Change Over Time 2015, 5, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugo, N.C. Overtourism at Heritage and Cultural Sites. In Overtourism; Séraphin, H., Gladkikh, T., Thanh, T.V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graffiti-Management-Policy.pdf. Available online: https://mvga-prod-files.s3.ap-southeast-4.amazonaws.com/public/2024-05/graffiti-management-policy.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Frey, B.S.; Briviba, A. Revived Originals—A proposal to deal with cultural overtourism. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 1221–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S.; Briviba, A. A policy proposal to deal with excessive cultural tourism. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 29, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, D.; Bērziņa, D.; Wright, A. Protecting a Broken Window: Vandalism and Security at Rural Rock Art Sites. Prof. Geogr. 2022, 74, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, J.; Pontille, D. Maintenance epistemology and public order: Removing graffiti in Paris. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2021, 51, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeShazo, J.L. Going beyond the usual suspects: Engaging street artists in policy design and implementation in Bogotá. Policy Des. Pr. 2022, 5, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flessas, T.; Mulcahy, L. Limiting Law: Art in the Street and Street in the Art. Law Cult. Humanit. 2018, 14, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderveen, G.; van Eijk, G. Criminal but Beautiful: A Study on Graffiti and the Role of Value Judgments and Context in Perceiving Disorder. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 2016, 22, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzate, J.R.; Tabares, M.S.; Vallejo, P. Graffiti and government in smart cities: A Deep Learning approach applied to Medellín City, Colombia. In International Conference on Data Science, E-learning and Information Systems 2021; ACM: Ma’an, Jordan, 2021; pp. 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobe, H.; Banis, D. Zero graffiti for a beautiful city: The cultural politics of urban space in San Francisco. Urban Geogr. 2014, 35, 586–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobe, H.; Conklin, T. Geographies of Graffiti Abatement: Zero Tolerance in Portland, San Francisco, and Seattle. Prof. Geogr. 2018, 70, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, D. Sustainable Graffiti Management Solutions for Public Areas. SAUC Str. Art Urban Creat. 2018, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combating_Graffiti.pdf. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/html/nypd/downloads/pdf/anti_graffiti/Combating_Graffiti.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- About the Task Force. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/html/nograffiti/html/aboutforce.html (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Toronto Municipal Code. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/municode/1184_485.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- City of Toronto. “Graffiti Management”, City of Toronto. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/services-payments/streets-parking-transportation/enhancing-our-streets-and-public-realm/graffiti-management/ (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- St. Lawrence Market BIA—City of Toronto’s Plan for Managing Graffiti Receives National Award. Available online: https://www.stlawrencemarketbia.ca/index.php/toronto-news/1047-city-of-toronto-s-plan-for-managing-graffiti-receives-national-award (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Vandalism-Graffiti-Management-Council-Policy.pdf. Available online: https://cdn.bunbury.wa.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Vandalism-Graffiti-Management-Council-Policy.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Community/StopTagsGraffiti (MapServer). Available online: https://gis.wcc.govt.nz/arcgis/rest/services/Community/StopTagsGraffiti/MapServer (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Wellington City Council. Graffiti Vandalism Management Plan. Available online: https://wellington.govt.nz/-/media/your-council/plans-policies-and-bylaws/plans-and-policies/a-to-z/graffitimanagement/files/graffiti-vandalism-management-plan.pdf?la=en&hash=F668E35487D409FDE3C7C92B5E7D7CDD4D2A7BBF (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Barcelona and Urban Art, an Achievable Entente|Barcelona Metròpolis. Available online: https://www.barcelona.cat/bcnmetropolis/2007-2017/en/calaixera/reports/barcelona-i-lart-urba-lentesa-possible/ (accessed on 22 November 2024).

| Authors/Year | Title |

|---|---|

| A.M.D. Jong, A. Iyer, D. Yates 2024 | Heritage and Criminal Sanctions |

| D. Chylińska, G. Kosmala 2023 | The ‘I was Here’ Syndrome in Tourism: The Case of Poland |

| J.L. DeShazo 2022 | Going beyond the usual suspects: engaging street artists in policy design and implementation in Bogotá |

| M.H. Mustafa, R.M. Al-Rousan, F.A. Bala’awi 2022 | They Were Here: Graffiti by Tourists in the Ancient City of Jerash, Jordan |

| H. Mekonnen, Z. Bires, K. Berhanu 2022 | Practices and challenges of cultural heritage conservation in historical and religious heritage sites: evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia |

| D. Yates, D. Bērziņa, A. Wright 2022 | Protecting a Broken Window: Vandalism and Security at Rural Rock Art Sites |

| J.R. Alzate, M.S. Tabares, P. Vallejo 2021 | Graffiti and government in smart cities: a Deep Learning approach applied to Medellín City, Colombia |

| J. Denis and D. Pontille 2021 | Maintenance epistemology and public order: Removing graffiti in Paris |

| B.S. Frey, A. Briviba, 2021 | Revived Originals—A proposal to deal with cultural overtourism |

| B.S. Frey, A. Briviba 2021 | A policy proposal to deal with excessive cultural tourism |

| R. AlMasri, A. Ababneh 2021 | Heritage Management: Analytical Study of Tourism Impacts on the Archaeological Site of Umm Qais—Jordan |

| N.C. Hugo 2020 | Overtourism at Heritage and Cultural Sites |

| T. Flessas, L. Mulcahy 2018 | Limiting Law: Art in the Street and Street in the Art |

| H. Shobe, T. Conklin 2018 | Geographies of Graffiti Abatement: Zero Tolerance in Portland, San Francisco, and Seattle |

| S.-U. Petronela, I. Sandu, L. Stratulat 2017 | The conscious deterioration and degradation of the cultural heritage |

| G. Vanderveen and G. van Eijk 2016 | Criminal but Beautiful: A Study on Graffiti and the Role of Value Judgments and Context in Perceiving Disorder |

| J.I. Ross 2016 | How major urban centers in the United States respond to graffiti/street art |

| D. Chatzigiannis 2015 | Vandalism of Cultural Heritage: Thoughts Preceding Conservation Interventions |

| G. Marche 2014 | Local democracy and public spaces in contest: Graffiti in San Fracisco |

| H. Shobe, D. Banis 2014 | Zero graffiti for a beautiful city: the cultural politics of urban space in San Francisco |

| L. Grove 2013 | “Heritocide? Defining and Exploring Heritage Crime” |

| K. Thompson, N. Offler, L. Hirsch, D. Every, M.J. Thomas, D. Dawson 2012 | From broken windows to a renovated research agenda: A review of the literature on vandalism and graffiti in the rail industry |

| S.O.C. Merrill 2011 | Graffiti at Heritage Places: Vandalism as Cultural Significance or Conservation Sacrilege |

| A. Young 2010 | Negotiated consent or zero tolerance? Responding to graffiti and street art in Melbourne |

| Type of Method | ||

|---|---|---|

| City/Country | Proactive | Reactive |

| New York, USA |

|

|

| Toronto, Canada |

|

|

| Stockholm, Sweden |

|

|

| Bogotá, Colombia |

|

|

| Bunbury, Australia |

|

|

| Wellington, New Zealand |

|

|

| Melbourne, Australia |

|

|

| Barcelona, Spain |

|

|

| Type of Method | Effectiveness of Measures and Policies | |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| 1. Proactive | ||

| 1.1. Legislation |

|

|

| 1.2. Education and Public Awareness Raising |

|

|

| 1.3. Data Gathering |

|

|

| 1.4. Heritage Management |

|

|

| 1.5. Legal Art Sites |

|

|

| 2. Reactive | ||

| 2.1. Criminal Sanctions |

|

|

| 2.2. Graffiti Removal and Damage Repair |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raič, M.; Jelinčić, D.A. Types and Effectiveness of Public Policy Measures Combatting Graffiti Vandalism at Heritage Sites. Heritage 2025, 8, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8010018

Raič M, Jelinčić DA. Types and Effectiveness of Public Policy Measures Combatting Graffiti Vandalism at Heritage Sites. Heritage. 2025; 8(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaič, Marko, and Daniela Angelina Jelinčić. 2025. "Types and Effectiveness of Public Policy Measures Combatting Graffiti Vandalism at Heritage Sites" Heritage 8, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8010018

APA StyleRaič, M., & Jelinčić, D. A. (2025). Types and Effectiveness of Public Policy Measures Combatting Graffiti Vandalism at Heritage Sites. Heritage, 8(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8010018