Earthen Architectural Heritage in the Gourara Region of Algeria: Building Typology, Materials, and Techniques

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- There is a lack of familiarity with earthen architecture and the accumulated mystery surrounding the factors affecting the acceptance of earthen architecture [23]. Jean-Claud Morel identified at least sixty barriers to using earth as construction materials [31]; they were divided into six groups (economic, organizational, sociological, political, technical, and environmental).

- -

- There is a misreading and misunderstanding of the laws related to heritage. Algerian laws encourage heritage protection, starting with the highest legislation, the 2020 Constitution, in which Article 76 indicates that “The State protects the national tangible and intangible cultural heritage and works to safeguard it” [32]. Further, law No. 98-04, Article 08, relating to the protection of cultural heritage, states the following [33]: “Real estate cultural property that includes historical monuments, archaeological sites, and urban or rural groups is subject to the protection regime, which can be registered in the additional inventory list, classification, or creation of save sectors”. Thus, confusion occurs about real estate cultural property that is not subject to the mentioned protective regime but submission to Article 38: “Spaces that are characterized by a predominance of cultural property and that are inseparable from their natural surroundings are classified as a cultural park”.

2. The Context of Study

2.1. The Location of the Study Region

2.2. Historical Background of Gourara

2.3. Meteorological Conditions

2.3.1. Temperature

2.3.2. Winds

2.3.3. Humidity

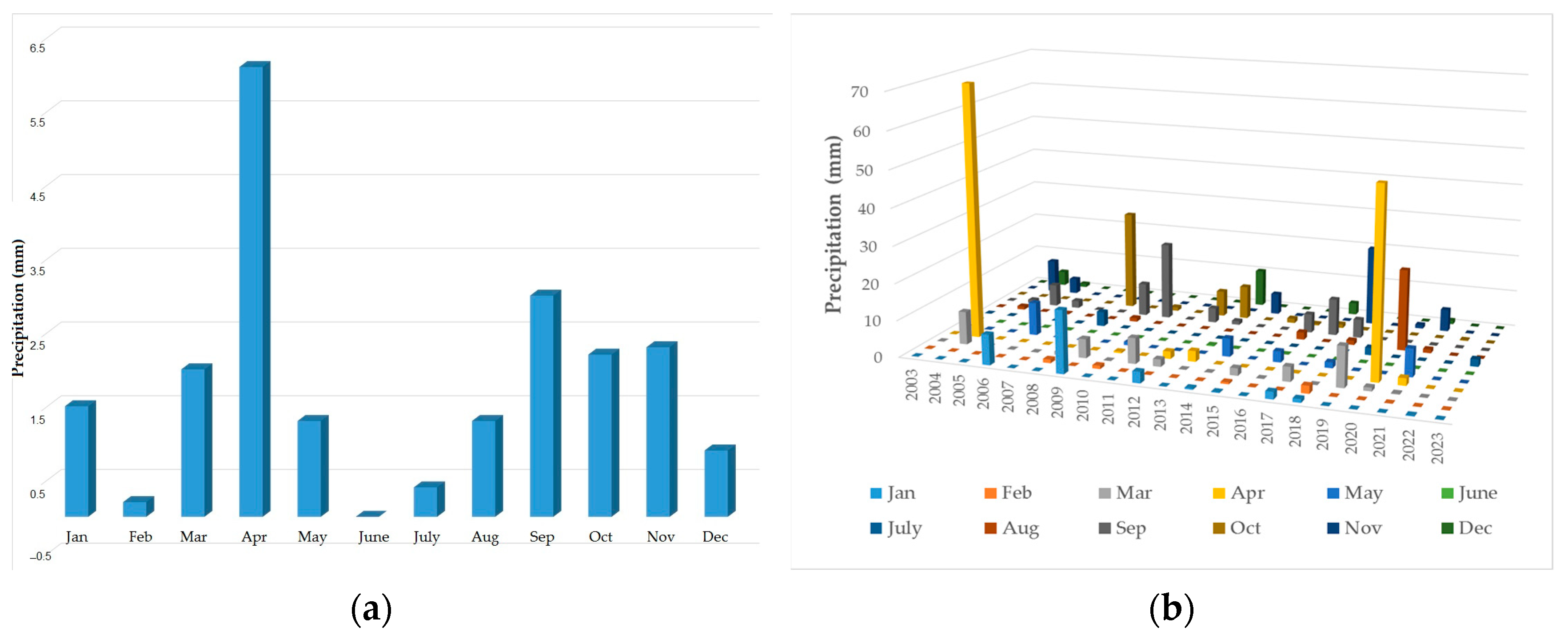

2.3.4. Precipitation

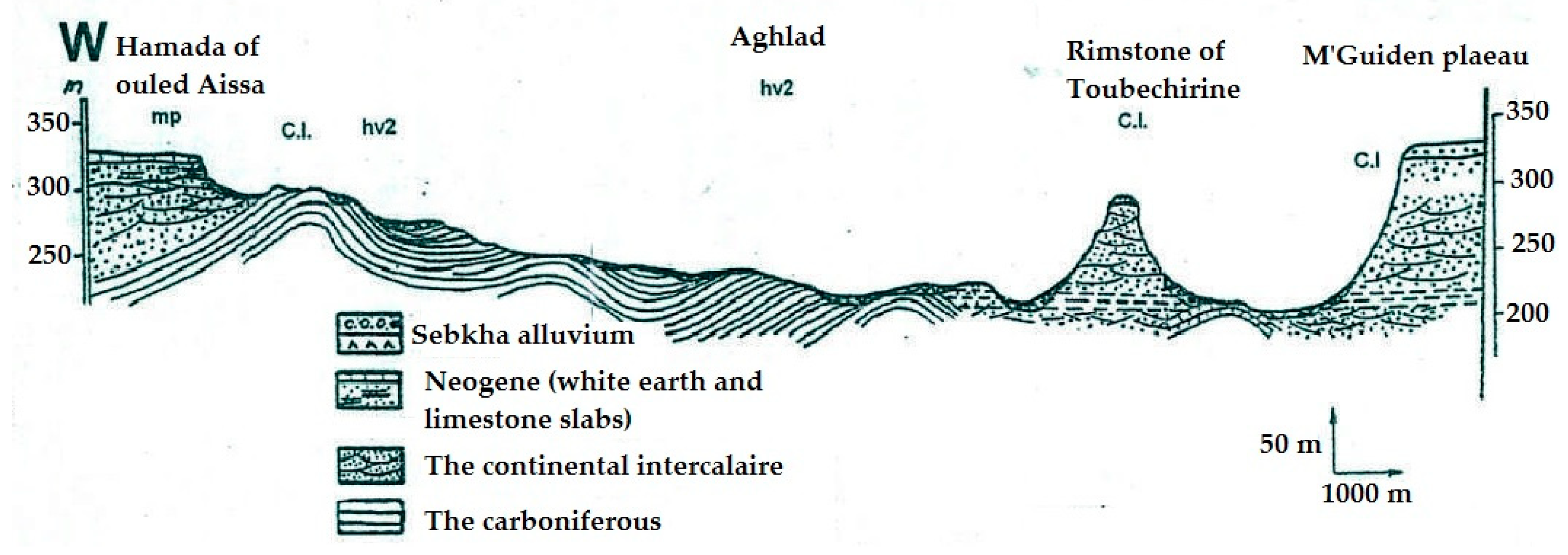

2.4. Geological Setting

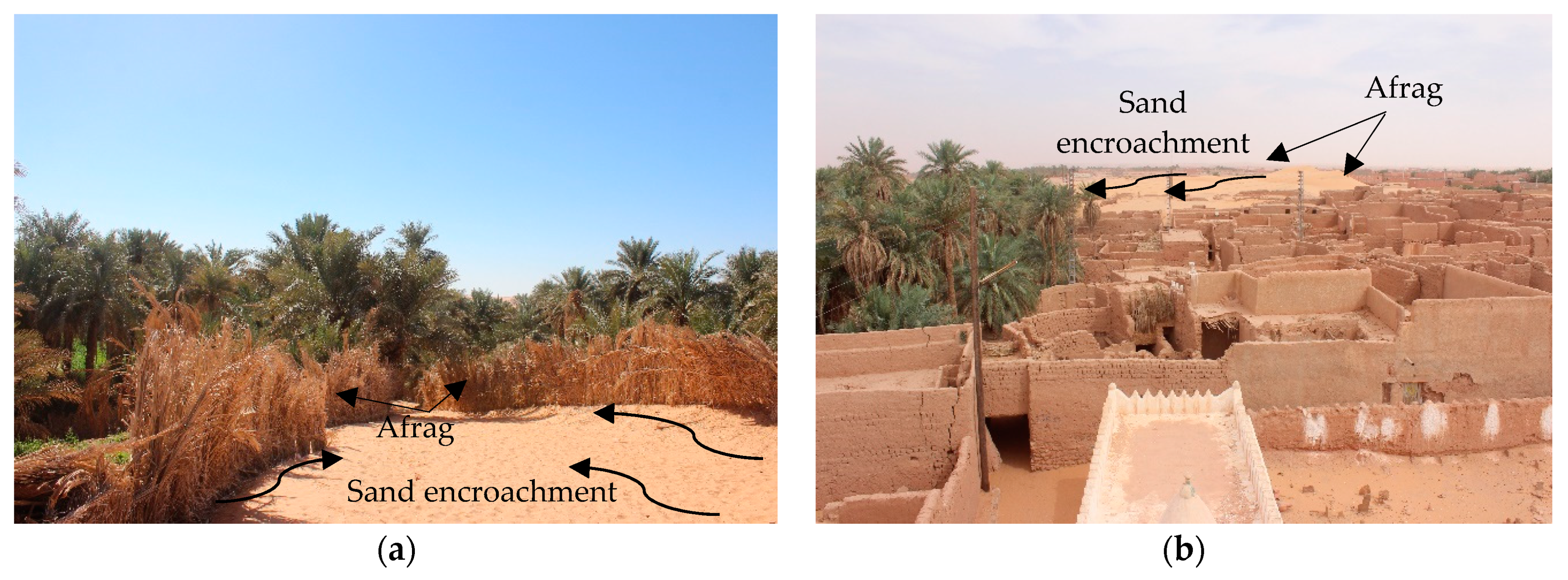

2.5. The Oasis System and Its Decline

2.5.1. Generalities

2.5.2. The Decline of the Oasis System

- (a)

- The transformations of social roles and systems (tribe, clan, family, and household), which were accompanied by changes in social practices [47].

- (b)

- The outbreak of the Algerian agricultural revolution in 1971 [48], which states the following:

- Article 1: Land belongs to those who serve it, and only those who cultivate it have the right to land.

- Article 3: All exploitative trade for water resources intended for agriculture shall be abolished.

- Article 13: The provisions of this order apply to all agricultural lands, regardless of their real estate system.

- Article 28: The right of ownership in any agricultural land or land intended for agriculture whose owner does not exploit it shall be canceled.

- (c)

- Reconsidering the EAH and its production, this period was characterized by the following:

- Due to stagnation that lasted for 43 years (1971–2014) and the fascination to which various media outlets contributed, and in light of the decline of volunteer work, concrete dominated the architectural and urban scene and the processes of intervention in heritage, without dispute, causing a deterioration of the EAH that had not been seen in centuries.

- Executive Decrees 14–27 were issued; these were related to the urban planning, architecture, and technique prescriptions applicable to construction in southern wilayas [51]. What is stated in Article 5 is especially noteworthy: “The prescriptions apply when the elaboration and revision of urban planning instruments and apply to the realization, transformation, extension, and renovation of all typologies of construction as well as space planning public in the municipalities of the southern wilayas”. There was hope of a new dawn for EAH. However, with the misreading of legislation, the situation soon paved the way for concrete buildings painted with the color of the earth and covered with earthen architectural elements under the name of the architectural production of EAH.

- The upgrading of the region to a wilaya (2019) raises another legislative concern about dealing with EAH, especially what is stated in Article 02: “The wilaya headquarters municipalities are excluded from applying the prescriptions contained in Executive Decree 14–27” [51]. This legislative omission may lead to the local authorities making wrong decisions regarding EAH.

- Petroleum discoveries in the region and their position on the priority scale of the country, which relies on hydrocarbons, were significant.

- This period concludes with issuing a legislative text related to the preservation and promotion of EAH, Executive Decree 23–401, which fixes the methods of preparing prescription books’ architectural features [52]. Article 6 states the following: “Local authorities prepare prescription books”. Further, Article 8 states the following: “The prescription books are prepared in two stages: diagnosis, such as identifying heritage characteristics and identifying extraneous and inconsistent elements”.

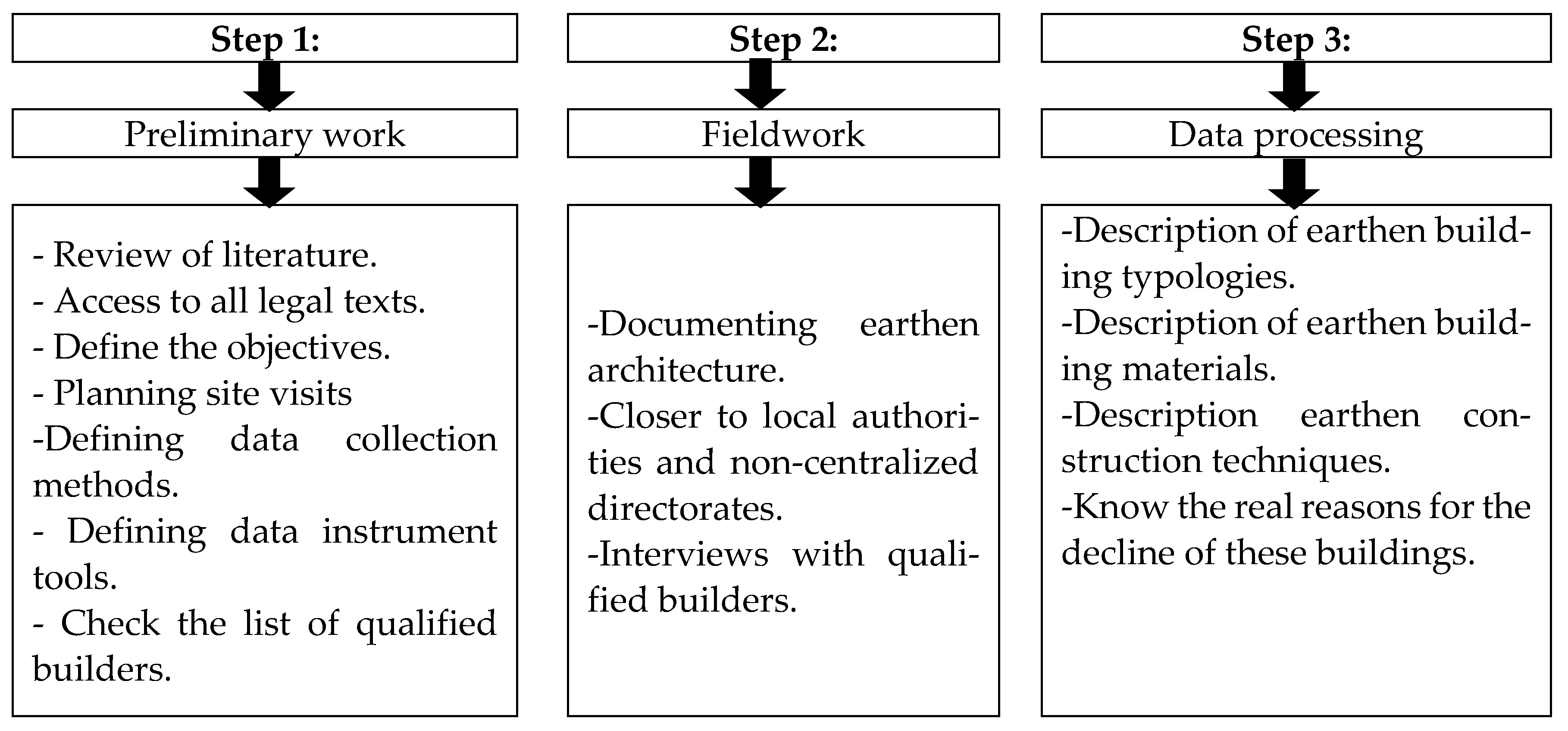

3. Materials and Methods

- Review of the literature on all aspects of EAH, including historical documents, cultural, human, and architectural values. It should be noted that most of what was recorded included military reports and human geography studies during the French occupation of the region.

- Access to all legal texts (official journal of the People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria) related to the protection of heritage, with knowledge of the authorities, their jurisdiction, and the relationship between them.

- Once the most critical aspects of the research are determined, the objectives are developed.

- Site visits, including escorts, seasons of the year, days of the week, times, and transportation methods, are planned.

- Data collection methods are defined, such as buildings positioned on a map and building codification.

- Data instrument tools are defined, such as laptops, cameras, camcorders, dictaphones, GPS, and notepads.

- A relationship is developed with the Algerian Centre for Cultural Heritage built in mud (CAPTERRE), and which is a public establishment created in 2012 under the Algerian Ministry of Culture and Arts guardianship. Its headquarters are in Timimoun, and its primary mission is to rehabilitate earthen architecture’s image by promoting and valorizing cultural heritage built on earth and the associated know-how [56]. Then, a list of qualified builders was obtained and checked; names, questions, and interview locations were defined.

- Visiting and documenting the buildings of the region.

- Becoming closer to local authorities and non-centralized directorates, such as the Directorate of Culture and Arts, the Directorate of Mujahideen and Rights Owners, and the Directorate of Urban Planning, Architecture, and Construction.

- Conducting two interviews with qualified builders and recording their experiences with earthen architecture and everything related.

- Data classification

- Description of earthen building typologies.

- Description of earthen building materials.

- Description of earthen construction techniques.

- Description of the real reasons for the decline of these buildings.

4. Results

4.1. Earthen Building Typology in the Gourara Region

4.1.1. Military Architecture

4.1.2. Civil Architecture

4.1.3. Religious Architecture

4.1.4. Funerary Architecture

4.2. Building Materials

4.2.1. Stones

- (a)

- Sandstone, locally called “Tafza”, is extracted from trenches or rocky plateaus where the Ighamawen is located and used for construction within the same context. At the same time, these grottoes (caves) are often used as summer dwellings.

- (b)

- Flat stones, locally called “Hajar Al-Safah”, are extracted from some rocky plateaus and limited locations. They were used to construct Ighamawen and cover the roofs of Muslim burial pits and their gravestones. Later, they began to be transported to the region’s capital (Timimoun) from the Ksar of Aghlad-Ouled Said, where their use became limited to decoration and funerary architecture.

- (c)

- Quartzite stones, locally called “Hajar Al-Sami”, which means deaf and nonporous stone, are known for their hardness and durability compared to the previous types. They were used in Ighamawen and are currently used mainly in construction. These stones are found in Hamada and on the plateau’s surface, like the Tademait plateau.

4.2.2. Clayey Soils

4.2.3. Wood

- (a)

- Trunk, locally called “Al-jada”, is a long, cylindrical, unbranched stem with a rough surface, petioles covering it, and a dense crown of big leaves at the top.

- (b)

- Fronds, similar to a huge feather, are the date palm’s leaves and consist of the following:

- b.1

- The blade, locally called “Al-Djerid”, refers to the upper part of the frond and consists of the following:

- -

- Midribs, locally called “Al-ʿaṣāy”, are the central veins of the fronds, entirely lacking in leaves and spines.

- -

- Leaves, locally called “Zaaf”, extend on both sides of the midribs.

- -

- Spines, locally called “Al-shwak”, are mutant leaves of varied lengths that grow between the leaf’s tip and its base.

- b.2

- The leaf base represents the lower part of the frond, and is composed of the following:

- -

- Petiole, locally called “Al-Karnaf”, is the base of the frond.

- -

- The leaf sheath, locally called “Al-Fadam”, is a fiber network that surrounds the petiole.

4.2.4. Lime

4.2.5. Vegetal Fibers

4.2.6. Animal Hides

4.3. Methods and Techniques of Building Components in the Region’s Structures

4.3.1. Foundations

- (a)

- The rocky plateau as a foundation: This type of foundation usually exists in military architecture. Plateaus are either built with earthworks or without them; so, foundations are built with them or without them (Figure 18).

- (b)

- Stone foundations: these are the most common type currently in the region. It appears evident that the presence of foundations in the region’s buildings is not linked to the type of soil (Figure 19); the soil may be rocky with or without foundations, and it is built as follows:

- Excavating and preparing a trench in the ground, with depths ranging from 0.5 to 1 m.

- Laying stones of various sizes and shapes in the trench, with the average thickness of the foundation from the bottom reaching up to 0.8 m, allowing for it to protrude above the ground surface to build walls.

4.3.2. Adobe Bricks

- Extract clayey soils by digging.

- The preparation of the clayey paste involves several steps:

- 2.1.

- Dry mixing with available sand or tuff.

- 2.2.

- Wet mixing with the addition of water.

- 2.3.

- Macerating the clayey paste for an extended period with periodic water additions.

- Shaping and molding.

- Sun drying.

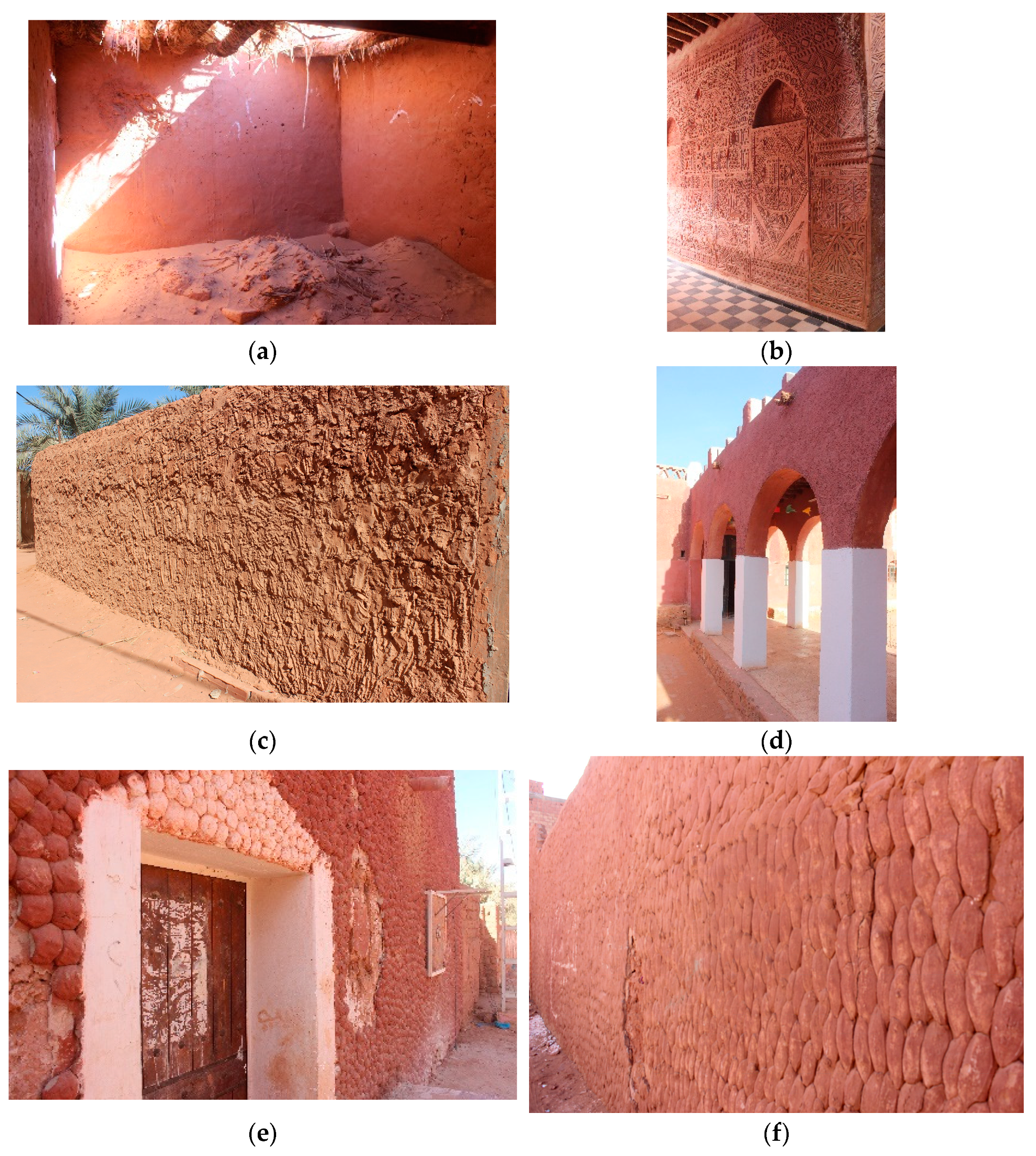

4.3.3. Walls

- (a)

- Stone walls: These are the most common type in the region, and according to oral tradition, buildings with stone walls are considered the oldest. This type of wall comes in two forms:

- Rubble stone walls: Undressed stones are used in this type of wall, with various sizes and types (Figure 21). The average thickness of the fortified walls at the base reaches about 0.8 m.

- The wheat spike wall’s method: This technique is rarely found in the region. Stones are arranged in a pattern resembling wheat grains in the spike, with a slope angle of up to 45° (Figure 22).

- (b)

- Mud walls: Based on the shape of the brick, they are classified into two types:

- Mud walls in the shape of a triangular prism: According to oral tradition, this technique is considered one of the oldest forms of mud walls in the region; they are manually formed, with dimensions of 0.1 × 0.1 × 0.1 m (Figure 23).

- Adobe brick walls: These are built from adobe bricks and mud mortar, and their thickness may reach 0.6 m. Whatever the brick sizes, walls in the region are in four shapes (Figure 24):

- -

- Stretcher bond: this bond is used on the first floor to separate between neighboring houses’ walls and does not exceed a height of 1.5 m. The thickness and height represent a social indicator of the level of safety and camaraderie among neighbors [28].

- -

- Header bond: this bond is used to separate different spaces within the house on floors and in the walls of the upper floor overlooking the alleys.

- -

- English bond with one brick wall: this bond is used for the same purpose as the header bond;

- -

- English bond with one and a half brick walls: this bond is used especially on the exterior walls facing the streets on the ground floor.

- (c)

- Mixed walls: This involves mixing different irregularly shaped and sized building materials within the same wall (Figure 25), and requires the filling of gaps with suitable stones or bricks and bonding them with mortar. Then, walls are covered to conceal any inconsistencies in the parts and enhance their appearance, although sometimes they may remain uncovered.

4.3.4. Buttress

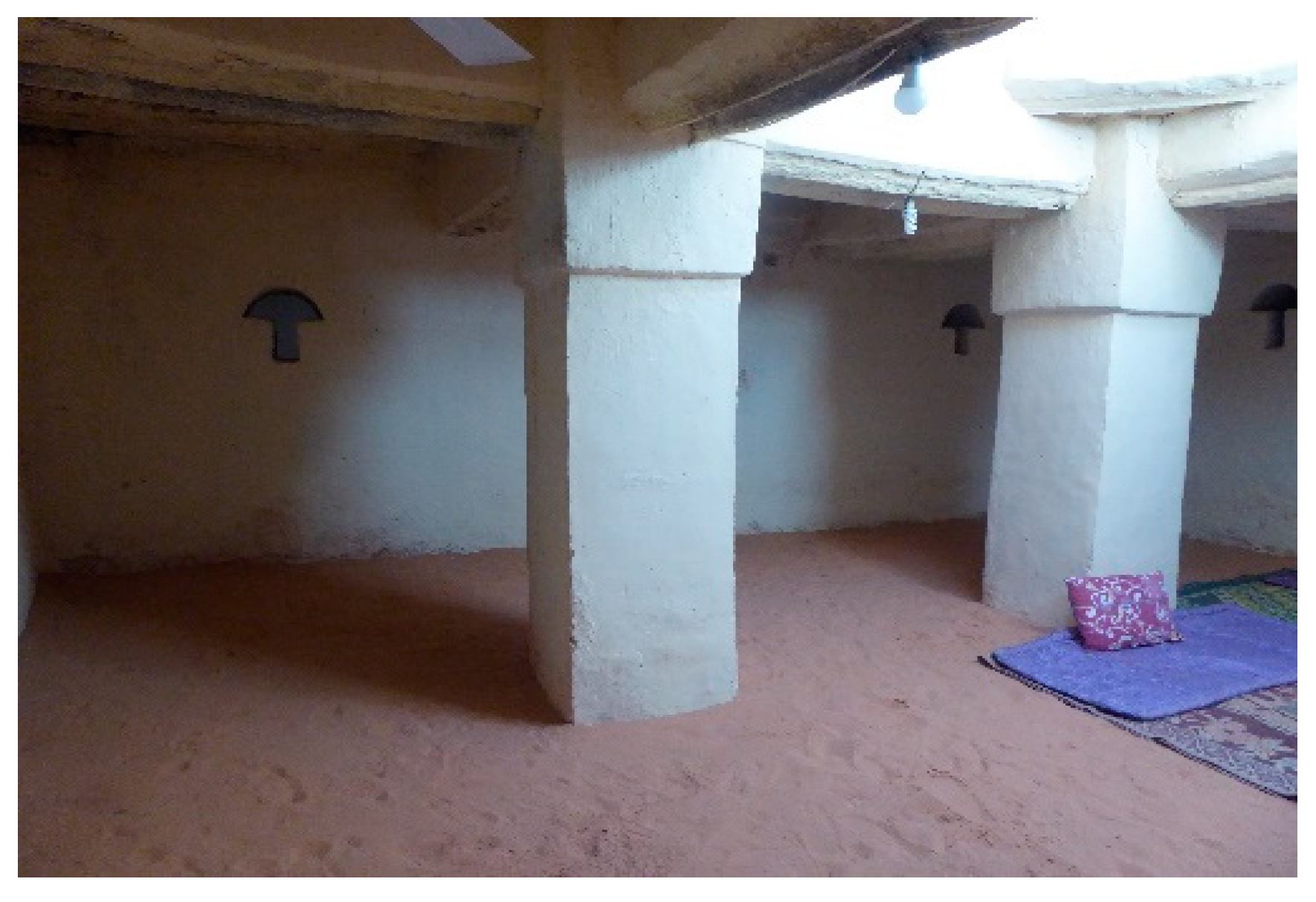

4.3.5. Columns and Arches

4.3.6. Door Installation

4.3.7. Staircase Construction Techniques

- (a)

- A built staircase: this is the most common method in the region due to its simplicity. The staircase is built between two walls, or between one side of the building and half of another wall, without using a balustrade (Figure 30). The gaps under the staircase are filled with soil and stones and can never be exploited, while the steps are gradually built up to reach the roofs.

- (b)

- A built staircase on an inclined roof of date palm trunks: After determining the inclination angle, the staircase is constructed on an inclined roof of date palm trunk beams supported on the upper side by the building’s wall and fixed at its lower end to a wall with built-in steps (Figure 31). The staircase steps are constructed using stones or adobe bricks, with a height ranging from 0.2 to 0.4 m. Utilizing the space under the staircase is one of the benefits of this technique.

4.3.8. Roofs

- (a)

- Date palm trunk roof: This type of roof uses date palm trunks as beams, with a length not exceeding 2.5 m, leaving a distance of 0.15 to 0.25 m between them. The beams are fixed with stones and mud mortar to prevent them from rotating on their axes. Then, various possible joists, which support wheat straw, leaf, or animal hides, are placed on top of the beams. They are covered with a thick layer of mud mortar, which does not exceed 0.50 m at most. This type varies in the following ways (Figure 32):

- After placing the beams, date palm midribs are positioned adjacently on top as joists without leaving space between them.

- After the beams are placed, date palm midribs are placed on top of them in the opposite direction, spaced by 0.15 m at most. Then, on top, the date palm blades are positioned adjacently in the same direction as the beams. These are the prevailing roofing methods in the Gourara region.

- After placing the beams and leaving a space between them of 0.4 m at most, segments of date palm trunks are positioned adjacently to each other on top of them as joists.

- After placing the beams and leaving a distance of 0.25 m between them at most, petioles are positioned adjacently to each other as joists. This method is considered foreign to the region, as these roofs were found in buildings constructed during the French occupation.

- The beams are placed adjacently to each other without leaving any space between them. This roofing method is commonly employed in religious architecture, mainly in Zawiyas.

- After the beams are placed, flat stones are placed on top as joists, and the distance between beams depends on the length of the stones used.

- After placing the beams and leaving a distance of 0.25 m between them at most, tree branches are put on top as joists.

- (b)

- Tree trunk roof: This type of roof is rarely used due to the mechanical properties of local tree trunk wood. Tree trunks are placed as beams (Figure 33), and flat stones are placed on top of them as joists, covered with mortar. Tree trunks may be used alongside date palm trunks on the same roof.

- (c)

- Stone roof: For this type of roof, flat stones are used as beams and joists simultaneously (Figure 34), covered with thick mortar. This technique is found in areas abundant in flat stones, such as the Ighamawen of Aghlad-Ouled Said.

- (d)

- Domed roof: The origin of domed roofs in the region can be traced back to the Negroland builders [63]. This is evident when comparing the shape of domes in the region with those in Negroland, such as the Djingarey Berre and Sankore mosques in Tombouctou and the Larabanga mosque in Ghana. This indicates the extension of African architecture to the region on the caravan trade route. Currently, building domes in the region is considered a disappearing skill.

4.3.9. Mud Plaster

4.3.10. Floors

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The necessity for local authorities to construct earthen architecture prototypes or restore earthen buildings is evidence of the level of awareness about preserving EAH. For example, in June 2024, the local authorities took the initiative to restore the Amghayr foggara.

- It is important to coordinate between the local authorities and CAPTERRE to organize volunteer workshops, previously carried out in 2016, 2018, 2019, 2021, and 2023, to urge residents to preserve their EAH.

- Heritage preservation should be promoted through various local media platforms.

- The notion of heritage preservation should be instilled in the younger generations.

- Emerging projects to protect and promote heritage should be facilitated through the Algerian Ministry of Knowledge Economy, Startups, and Micro Enterprises policies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Houben, H.; Guillaud, H. Traité de Construction en Terre, 3rd ed.; Parenthèses: Marseille, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Agyekum, K.; Kissi, E.; Danku, J.C. Professionals’ views of vernacular building materials and techniques for green building delivery in Ghana. Sci. Afr. 2020, 8, e00424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirhamzah, D.; Amrullah, S. Soil as material for the creation of humans, perspectives from the holy quran and science. J. Islam Sci. 2022, 9, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huysecom, E.; Hajdas, I.; Renold, M.A.; Synal, H.A.; Mayor, A. The “Enhancement” of Cultural Heritage by AMS Dating: Ethical Questions and Practical Proposals. Radiocarbon 2016, 59, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; He, Y. Research on the historical and cultural value of and protection strategy for rammed earth watchtower houses in Chongqing, China. Built Herit. 2021, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Charif, H.; Belakehal, A.; Sami, Z. Earthen Architecture in Southern Algeria: An Assessment of Social Values and the Impact of Industrial Building Practices. Open Archaeol. 2023, 9, 20220324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacko, O. The involvement of local communities in the conservation process of earthen architecture in the Sahel-Sahara region—The case of Djenné, Mali. Built Herit. 2021, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiels, T.L.G. Seismic Retrofitting Techniques for Historic Adobe Buildings. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2015, 9, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallipoli, D.; Bruno, A.W.; Bui, Q.B.; Fabbri, A.; Faria, P.; Oliveira, D.V.; Silva, R.A. Durability of Earth Materials: Weathering Agents, Testing Procedures and Stabilisation Methods. In Testing and Characterisation of Earth-based Building Materials and Elements: State-of-the-Art Report of the RILEM TC 274-TCE; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 211–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ccanccapa Puma, J.; Hidalgo Valdivia, A.V.; Espinoza Vigil, A.J.; Booker, J. Preserving Heritage Riverine Bridges: A Hydrological Approach to the Case Study of the Grau Bridge in Peru. Heritage 2024, 7, 3350–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileto, C.; López-Manzanares, F.V.; Cristini, V.; Soriano, L.G. Earthen architecture in the Iberian Peninsula: A portrait of vulnerability, sustainability and conservation. Built Herit. 2021, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, M.; Guerrero, L.; Crosby, A. Technical Strategies for Conservation of Earthen Archaeological Architecture. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2015, 17, 224–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Lun, Y. Using traditional knowledge to reduce disaster risk—A case of Tibetans in Deqen County, Yunnan Province. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 108, 104492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Martin, O.; Fuentes-Porto, A.; Martin-Gutierrez, J. A Digital Reconstruction of a Historical Building and Virtual Reintegration of Mural Paintings to Create an Interactive and Immersive Experience in Virtual Reality. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch’ng, E.; Feng, P.; Yao, H.; Zeng, Z.; Cheng, D.; Cai, S. Balancing Performance and Effort in Deep Learning via the Fusion of Real and Synthetic Cultural Heritage Photogrammetry Training Sets. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence—ICAART, Vienna, Austria, 2–4 February 2021. Special Session on Artificial Intelligence and Digital Heritage: Challenges and Opportunities—ARTIDIGH. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfadaly, A.; Attia, W.; Qelichi, M.M.; Murgante, B.; Lasaponara, R. Management of Cultural Heritage Sites Using Remote Sensing Indices and Spatial Analysis Techniques. Surv. Geophys. 2018, 39, 1347–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaia, E.; Maietti, F.; Di Giulio, R.; Schippers-Trifan, O.; Van Delft, A.; Bruinenberg, S.; Olivadese, R. BIM-based Cultural Heritage Asset Management Tool. Innovative Solution to Orient the Preservation and Valorization of Historic Buildings. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2020, 15, 1734686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folorunso, C.A. Globalization, Cultural Heritage Management and the Sustainable Development Goals in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Nigeria. Heritage 2021, 4, 1703–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Camacho, D.; Jung, J.E. Identifying and ranking cultural heritage resources on geotagged social media for smart cultural tourism services. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2017, 21, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Center for Earthen Construction (CRATerre-EAG). 2024. Available online: https://www.craterre.org (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- The Getty Conservation Institute. 2024. Available online: https://www.getty.edu/conservation. (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM). 2024. Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/ (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Sharif, Z.M. A Conceptual Framework Outlining Factors Affecting the Acceptance of Earth as a Sustainable Building Material in the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 9, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaud, H. De Traces en Repères Choisis: Eloge Terrestre de la Brique Crue, in Les Cultures Constructives de la Brique Crue: Troisièmes Echanges Transdisciplinaires sur les Constructions en Terre Crue, Acte de Table-Ronde de Toulouse 16 et 17 Mai 2008; Chazelles, C.-A.D., Klein, A., Pousthomis, N., Eds.; Éditions de l’Espérou: Montpellier, France, 2011; pp. 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage, M. L’architecture de Brique Crue en Mésopotamie, in Les Cultures Constructives de la Brique Crue: Troisièmes Echanges Transdisciplinaires sur les Constructions en Terre Crue, Acte de Table-Ronde de Toulouse 16 et 17 Mai 2008; Chazelles, C.-A.D., Klein, A., Pousthomis, N., Eds.; Éditions de l’Espérou: Montpellier, France, 2011; pp. 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Vitruve. Les Dix Livres d’Architecture de Vitruve, Corrigez et Traduits Nouvellement en Français, avec des Notes et des Figures, par Claude Perrault; Jean Baptiste Coignard: Paris, France, 1673. [Google Scholar]

- Fodde, E. Traditional Earthen Building Techniques in Central Asia. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2009, 3, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouamar, A. Interview on Local Indigenous Building Practices of Earthen Technique and Materials; Kassou, Y., Ed.; Ksar Badrian: Wilaya de Timimoun, Algeria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yves, G. Survie et ordre social au Sahara: Les oasis du Touat-Gourara-Tidikelt en Algérie. Cah. Des Sci. Hum. 1993, 29, 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Samarasinghe, D.A.S.; Falk, S. Promoting Earth Buildings for Residential Construction in New Zealand. Buildings 2022, 12, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, J.C.; Charef, R.; Hamard, E.; Fabbri, A.; Beckett, C.; Bui, Q.B. Earth as construction material in the circular economy context: Practitioner perspectives on barriers to overcome. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20200182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constitution de la republique algerienne democratique et populaire. J. Off. Repub. Alger. 2020, 15, 2–49.

- Loi n° 98-04 du 20 Safar 1419 correspondant au 15 juin 1998 relative a la protection du patrimoine culturel. J. Off. Repub. Alger. 1998, 44, 3–15.

- Loi n° 19-12 du 14 Rabie Ethani 1441 correspondant au 11 décembre 2019 modifiant et complétant la loi n° 84-09 du 4 février 1984 relative à l’organisation territoriale du pays. J. Off. Repub. Alger. 2019, 78, 12–15.

- Reboul, E. Le Gourara, Étude historique, géographique et médicale. Arch. L’institut Pasteur D’algérie 1953, 31, 164–246. [Google Scholar]

- Rachid, B. Les Oasis du Gourara (Sahara Algérien) II; Fondation des Ksour; Peeters Press Louvain: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Daumas, E. Le Sahara Algérien: Études Géographiques, Statistique et Historique sur la Région au sud des Établissements Français en Algérie; Fortin, Masson et Cie: Paris, France, 1845. [Google Scholar]

- Colomb, L.-C.D. Notice sur les Oasis du Sahara et les Routes Qui y Conduisent; Imprimerie de Ch. Lahure et Cie: Paris, France, 1860. [Google Scholar]

- Donné Météorologique de Timimoun, 2003–2023. Office National de la Météorologie, Station Météorologique de Timimoun. Non Publié.

- Bisson, J. Le Gourara: Etude de géographie humaine. In Institut de Recherches Sahariennes; Université d’Alger: Alger Centre, Algérie, 1957; 222p. [Google Scholar]

- Regional Geology of Timimoun, Oued Mya, and Berkine Basins. 2024. Available online: https://www.alnaft.dz/en/842/saharan-domain (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Nedjari, A.; Ouali, R. Le gourara -timimoun: De la syneclise hercynienne atypique aux continentaux. Mém. Serv. Géol. L’algerie 2018, 20, 4–50. [Google Scholar]

- Côte, M. Signatures Sahariennes: Terroirs & Territoires vus du Ciel; Presses Universitaires de Provence: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zuhayli, W. Usul al-Fiqh al-Islami, 1st ed.; Dar al-Fikr lil-Taba’a wa al-Tawzi’ wa al-Nashr: Damascus, Siria, 1986; Volume Al-juz’ 02. [Google Scholar]

- Faraj, F.M. Iqlim Tuwat Khalan al-Qarnayn al-Thamin ‘Ashar wa al-Tasi’un al-Miladiyyin, ma’a Tahqiq Kitab al-Qawl al-Basit fi Akhbar Tamanatit (Muhammad bin baba haydah); Diwan al-Matbu’at al-Jami’iyya: Al-Jaza’ir, Algeria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Terki, Y. Catalogue d’Exposition de Terre et d’Argile; Ministère de la Culture, Ed.; Les Presses de l’Lmprimerie en Nakhla: El Achour, Alger, 2013; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Tabii, I. Athar al-’Imarat al-Ihtilaliyah fi Tatawwur al-Mumarakat al-Ijtima’iyah fi al-Qusur al-’Atiqah, Dirasat Halat Madinah Biskrah, in Architecture. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Mohamed Khider Biskra, Biskra, Algeria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ordonnance n° 71-73 du 8 novembre 1971 portant Révolution agraire. J. Off. Repub. Alger. 1971, 97, 1270–1300.

- Décret présidentiel n° 92-44 du 9 février 1992 portant instauration de l’état d’urgence. J. Off. Repub. Alger. 1992, 10, 222–223.

- Ordonnance n° 11-01 du 20 Rabie El Aouel 1432 correspondant au 23 février 2011 portant levée de l’état d’urgence. J. Off. Repub. Alger. 2011, 12.

- Décret exécutif ° 14–27 du Aouel Rabie Ethani 1435 correspondant au 1er février 2014 fixant les prescriptions urbanistiques, architecturales et techniques applicables aux constructions dans les wilayas du Sud. J. Off. Repub. Alger. 2014, 6, 3–8.

- Décret exécutif n° 23–401 du 25 Rabie Ethani 1445 correspondant au 9 novembre 2023 fixant les modalités d’élaboration des cahiers de prescriptions particulières architecturales. J. Off. Off. Repub. Alger. 2023, 72, 16–17.

- Mousourakis, A.; Arakadaki, M.; Kotsopoulos, S.; Sinamidis, I.; Mikrou, T.; Frangedaki, E.; Lagaros, N.D. Earthen Architecture in Greece: Traditional Techniques and Revaluation. Heritage 2020, 3, 1237–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Calvillo, A.; Alonso-Guzman, E.M.; Solís-Sánchez, A.; Martinez-Molina, W.; Navarro-Ezquerra, A.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, B.; Arreola-Sanchez, M.; Sandoval-Castro, K. Use of Audiovisual Methods and Documentary Film for the Preservation and Reappraisal of the Vernacular Architectural Heritage of the State of Michoacan, Mexico. Heritage 2023, 6, 2101–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Tapiero, J.C.; Graus, S.; Khei, S.; Silva, D.; Conde, O.; Ferreira, T.M.; Ortega, J.; Luso, E.; Rodrigues, H.; Vasconcelos, G. An ICT-Enhanced Methodology for the Characterization of Vernacular Built Heritage at a Regional Scale. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Cultural Heritage Built in Mud (CAPTERRE), Algerian Ministry of Culture and Arts. 2024. Available online: https://www.capterre.dz (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Arifi, M. Interview on Local Indigenous Building Practices of Date Palm Tree Treatment and Tanning Process; Kassou, Y., Ed.; Algerian Center for Cultural Heritage Built in Mud (CAPTERRE): Timimoun, Algeria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Loi n° 03-10 du 19 Joumada El Oula 1424 correspondant au 19 juillet 2003 relative à la protection de l’environnement dans le cadre du développement durable. J. Off. Repub. Alger. 2003, 43, 6–19.

- Loi n° 08-16 du Aouel Chaâbane 1429 correspondant au 3 août 2008 portant orientation agricole. J. Off. Repub. Alger. 2008, 46, 3–12.

- Décret exécutif n° 93-285 du 9 Joumada Ethania 1414 correspondant au 23 novembre 1993 fixant la liste des espèces végétales non- cultivées protégées. J. Off. Repub. Alger. 1993, 78, 7–17.

- Dabaieh, M. Earth vernacular architecture in the Western Desert of Egypt. In VERNADOC RWW 2002; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2013; pp. 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Ibrahim al-Lakhmi, k.a.I.a.-R.a.-B. Al-I’lan bi-Ahkam al-Bunyan; Markaz al-Nashr al-Jami’i: Tunis, Tunisia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Le Commandant Cauvet, G. Les marabouts, petits monuments funéraires et votifs du nord de l’Afrique (suite). Rev. Afr. 1923, 64, 448–522. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kassou, Y.; Alkama, D.; Bouzaher, S. Earthen Architectural Heritage in the Gourara Region of Algeria: Building Typology, Materials, and Techniques. Heritage 2024, 7, 3821-3850. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7070181

Kassou Y, Alkama D, Bouzaher S. Earthen Architectural Heritage in the Gourara Region of Algeria: Building Typology, Materials, and Techniques. Heritage. 2024; 7(7):3821-3850. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7070181

Chicago/Turabian StyleKassou, Younes, Djamel Alkama, and Soumia Bouzaher. 2024. "Earthen Architectural Heritage in the Gourara Region of Algeria: Building Typology, Materials, and Techniques" Heritage 7, no. 7: 3821-3850. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7070181

APA StyleKassou, Y., Alkama, D., & Bouzaher, S. (2024). Earthen Architectural Heritage in the Gourara Region of Algeria: Building Typology, Materials, and Techniques. Heritage, 7(7), 3821-3850. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7070181