Applying Inclusive Design and Digital Storytelling to Facilitate Cultural Tourism: A Review and Initial Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Developing Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Systematic Searches in Different Databases

2.3. Importing Search Results into Individual Bibliographic Software, Documenting the Search, and the Deletion of Duplicates

2.4. Organization of Relevant and Irrelevant Articles

2.5. Searching for Additional Articles, Books, and Policies Using Other Forms of Searching

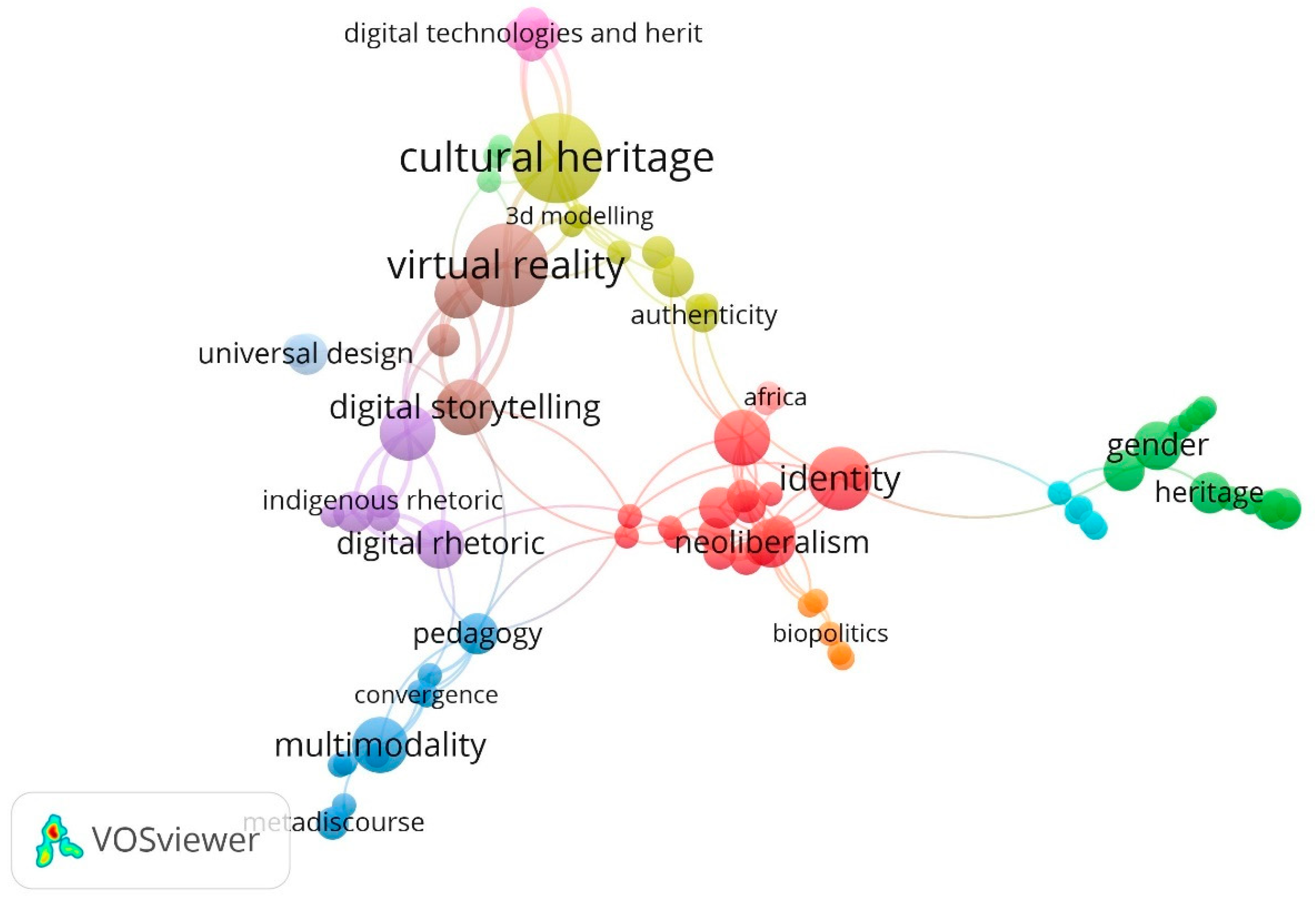

3. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis

4. Content analysis

| Areas | Details and Research |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Diversity | |

| Theme 2: Motivation | |

| Theme 3: Management and funding | |

| Theme 4: Marketing and branding |

|

| Theme 5: Personal experience |

4.1. Issues in Cultural Tourism: Five Themes

4.2. Diversity in Museums: Four Themes

- Theme 1: Demographic aspects

- Theme 2: Learning aspects

- Theme 3: Purposive aspects

- Theme 4: Motivational aspects

| Demographic Aspects | Loden et al. [55]; Gardenswartz et al. [56] | 1. Personality (general behavior when interacting with others) | 2. Internal dimension (age, gender, physical ability, etc.) | 3. External dimension—affecting decision-making (education, marital status, place of residence, etc.) | 4. Organizational dimension (positioning of working) | |||

| Kasemsarn and Nickpour [58] | 1. People with disabilities: those with symptoms relating to any of the following: vision, hearing, mobility, mental health, intellectual function, cognition/learning, and long-term health conditions | 2. Cultural tourists: those who engage in cultural tourism with more than four trips per year | 3. Older adults: people over 60 years old | 4. People uninterested in cultural tourism (noncultural tourists): those who engage in cultural tourism with fewer than four trips per year | 5. Youths: people 15–24 years old | |||

| Learning Aspects | Levasseur and Veron [59] | 1. The ant visitor: spends much time on one particular exhibition | 2. The butterfly visitor: visits all exhibitions with varied focus | 3. The grasshopper visitor: visits only exhibition areas of interest | 4. The fish visitor: visits most of the exhibitions briefly | |||

| Umiker-Sebeok [65] | 1. The pragmatic: interested in in-depth information | 2. The critical: interested in the aesthetics of the exhibitions | 3. The utopian: interested in social interaction | 4. The diversionary: have the goal of having fun at the exhibitions | ||||

| Gardner [60] | 1. The linguistic: prefers written material | 2. The logical-mathematical: prefers diagrams | 3. The spatial: prefers reading maps | 4. The musical: prefers learning through visual and interactive media | ||||

| McCarthy [61] | 1. The analytical: prefers facts | 2. The common sense: prefers theories | 3. The imaginative: prefers listening and social interaction | 4. The experiential: prefers learning by trial and error | ||||

| Purposive Aspects | Falk and Dierking [62] | 1. Professionals/Hobbyists: feels a relationship between the exhibition and their profession/hobby | 2. Explorers: are curious to learn, but not experts | 3. Respectful pilgrims: focus on what is represented as a memorial | 4. Affinity seekers: are motivated by heritage | 5. Facilitators: are socially motivated | 6. Experience seekers: are collecting experiences through museums | 7. Rechargers: are seeking restorative experience |

| Motivational Aspects | Stein, Garibay, and Wilson [63] | 1. Home country values: feeling comfortable in a related home exhibition | 2. Community cultural values: spending time with family or social interaction | 3. Educational values: seeing museums as educational places | 4. Cultural identity values: feeling a strong connection with culture | |||

| Han [64] | 1. The community: wants to know about the origins of Chinatown in the US | 2. The national: wants to know about Chinese immigration to the US | 3. The global: wants to know about the Chinese immigrant journey worldwide | |||||

4.3. Inclusive Design in Museums: 5 Themes

- Theme 1: understanding older adults

- Theme 2: understanding people with disabilities

- Theme 3: understanding youth

- Theme 4: understanding barriers and drivers of visitors

- Theme 5: understanding the lifestyles and behaviors of visitors

4.4. Motivation in Museums: Two Themes

- Theme 1: push and pull motivation

- Theme 2: push and pull strategies applied with digital storytelling

4.5. Digital Storytelling in Museums: Seven Themes

- Theme 1: digital storytelling for both online and on-site museums

- Theme 2: digital storytelling at museums from 2000 to 2010

- Theme 3: digital storytelling at museums from 2010 to the present

- Theme 4: increasing accessibility

- Theme 5: re-create no longer existing places

- Theme 6: creating a city’s digital memories

- Theme 7: Digital storytelling with the latest technology

5. Conclusions

- Issues in cultural tourism

- Diversity in museums

- Inclusive design in museums

- Motivation in museums

- Digital storytelling in museums

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNWTO. International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics Draft Compilation Guide. 2008. Available online: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/tradeserv/egts/CG/IRTS%20compilation%20guide%207%20march%202011%20-%20final.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Kasemsarn, K.; Nickpour, F. Inclusive Digital Storytelling to Understand Audiences’ Behaviours. Int. J. Vis. Des. 2017, 11, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, E.; Sisto, R.; Bianchi, P.; Cappelletti, G. Inclusivity and responsible tourism: Designing a trademark for a national park area. Sustainability 2020, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergori, A.S.; Arima, S. Cultural and non-cultural tourism: Evidence from Italian experience. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Design Council, Inclusive Design Education Resource. Design Council, London. 2008. Available online: UK.https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-work/skills-learning/resources/principles-inclusive-design/ (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Clarkson, P.J.; Coleman, R. History of inclusive design in the UK. Appl. Ergon. 2015, 46, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikus, J.; Høisæther, V.; Martens, C.; Spina, U.; Rieger, J. Employing the inclusive design process to design for all. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, San Diego, CA, USA, 16–20 July 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.; Joseph, G.; Farnaz, N. What Is Psychosocially Inclusive Design? A Definition with Constructs. Design J. 2020, 24, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corallo, A.; Esposito, M.; Marra, M.; Pascarelli, C. Transmedia digital storytelling for cultural heritage visiting enhanced experience. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality and Computer Graphics, Santa Maria al Bagno, Italy, 24–27 June 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C.H. Digital Storytelling: A Creator’s Guide to Interactive Entertainment; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ohler, J.B. Digital Storytelling in the Classroom: New Media Pathways to Literacy, Learning, and Creativity; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, P. The storyteller in context: Storyteller identity and storytelling experience. Storytell. Self Soc. 2008, 4, 64–87. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, A.M.; Mc Guckin, C. The Systematic Literature Review Method: Trials and Tribulations of Electronic Database Searching at Doctoral Level; SAGE Research Methods Cases Part 1; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsarn, K. A Framework for Inclusive Digital Storytelling for Cultural Tourism in Thailand. Ph.D. Thesis, Brunel University London, Uxbridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Domšić, L. Participatory Museum Projects with Young People: Measuring the Social Value of Participation. Int. J. Incl. Mus. 2021, 14, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greffe, X. Concept Study on the Role of Cultural Heritage as the Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development; Suscult: Venice, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kasemsarn, K. Creating a Cultural Youth Tourism eBook Guidelines with Four Design Factors. Int. J. Vis. Des. 2022, 16, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, W.A.R.W.M.; Suhaimi, A.I.H.; Mokhtarudin, A.; Luaran, J.E.; Zulkipli, Z.A. Designing Augmented Reality for Malay Cultural Artifact using Rapid Application Development. In Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, N.M.; Ryder, M.E. “Ebilities” tourism: An exploratory discussion of the travel needs and motivations of the mobility-disabled. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, M.K.; McKercher, B.; Packer, T.L. Traveling with a disability: More than an access issue. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, B. Public participation in community tourism planning. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, M. Accessible Geotourism: Constraints and implications. In The Geotourism Industry in the 21st Century; Apple Academic Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.-E. Understanding the discrimination experienced by customers with disabilities in the tourism and hospitality industry: The case of Seoul in South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, J.T.; Morrison, A.M.; Alzua, A. Cultural and heritage tourism: Identifying niches for international travelers. J. Tour. Stud. 1998, 9, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhrana, A.; Ridho, Z. Sustainable cultural tourism development: A strategic for revenue generation in local communities. J. Econ. Trop. Life Sci. 2020, 4, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, H.; Beisswenger, C.; Partarakis, N.; Zabulis, X.; Adami, I.; Zidianakis, E.; Patakos, A.; Patsiouras, N.; Karuzaki, E.; Foukarakis, M.; et al. Multimodal Narratives for the Presentation of Silk Heritage in the Museum. Heritage 2022, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M. From camaraderie to the cash nexus: Economic reforms, social stratification and their political consequences in China. J. Contemp. China 1999, 8, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tešin, A.; Kovačić, S.; Pivac, T.; Vujičić, M.D.; Obradović, S. From children to seniors: Is culture accessible to everyone? Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 15, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calinao, D.J.; Lin, H.W. Fashion-Related Exhibitions and Their Potential Role in Museum Marketing: The Case of Museums in Taipei, Taiwan. Int. J. Incl. Mus. 2018, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentschler, R.; Hede, A.-M. Museum Marketing: Competing in the Global Marketplace; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rizvic, S.; Saszak, A.; Ramic-Brkic, B.; Hulusic, V. Virtual museums and their public perception in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2011, 38, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, P.L.; Wong, E.; Polonsky, M.J. Marketing cultural attractions: Understanding non-attendance and visitation barriers. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2009, 27, 833–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezgaile, A.; Grinberga, K.; Singh, N.; Livina, A. A Study on Youth Behavior Towards the North Vidzeme Biosphere Reserve in Latvia. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2021, 12, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Cheng, C.-K.; O’Leary, J.T. Understanding participation patterns and trends in tourism cultural attractions. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1366–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, H.; Kamaruddin, N. A Conceptual Framework of Digital Storytelling (Dst) Elements on Information Visualisation (Infovis) Types in Museum Exhibition for User Experience (Ux) Enhancement. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 10, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halewood, C.; Hannam, K. Viking heritage tourism: Authenticity and commodification. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Cultural and heritage tourism: The great debates. In Tourism in the Twenty-First Century: Reflections on Experience; Continuum: London, UK, 2001; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gallaga, E.; Jorge, T.; Berislav, A. Archaeological Attractions Marketing: Some Current Thoughts on Heritage Tourism in Mexico. Heritage 2022, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Shukla, A. Problems and prospects of cultural tourism: A case study of Assam, India. Int. J. Phys. Soc. Sci. 2013, 3, 455. [Google Scholar]

- Danah, B. Why youth (heart) social network sites: The role of networked publics in teenage social life. In MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning—Youth, Identity, and Digital Media; Buckingham, D., Ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, E.; Alfonso, L. Realities and problems of a major cultural tourist destination in Spain, Toledo. Rev. Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2018, 16, 617–636. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.H.; Kao, Y.F.; Kuo, C.L. A multimedia storytelling in a rural village: The show Taiwan e-tourism service using tablet technologies. In Proceedings of the 2014 IIAI 3rd International Conference on Advanced Applied Informatics, Kokura, Japan, 31 August–4 September 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 525–526. [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger, Y.; Mavondo, F. Determinants of youth travel markets’ perceptions of tourism destinations. Tour. Anal. 2002, 7, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisorn, J. Study of the Conditions of Tourist Attractions in Order to Develop Tourism in Mae Hong Son Province. Ph.D. Thesis, Srinakharinwirot University, Bangkok, Thailand, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen, H.; Bires, Z.; Berhanu, K. Practices and Challenges of Cultural Heritage Conservation in Historical and Religious Heritage Sites: Evidence from North Shoa Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, D.A.; Elyamani, A.; Hassan, M.; Mourad, S. A Fund-Allocation Optimization Framework for Prioritizing Historic Structures’ Conservation Projects—An Application to Historic Cairo. In Proceedings of the Canadian Society of Civil Engineers Annual Conference, Laval, Montreal, QC, Canada, 12–15 June 2019; pp. 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Oppermann, M. Tourism destination loyalty. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uncles, M.D.; Dowling, G.R.; Hammond, K. Customer loyalty and customer loyalty programs. J. Consum. Mark. 2003, 20, 294–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, D. Proposing a Sustainable Marketing Framework for Heritage Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, N.; Kotler, P.; Wendy, I.K. Museum Marketing and Strategy. Designing Missions, Building Audiences, Generating Revenue and Resources, 2nd ed.; Josey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Prebensen, N.K.; Woo, E.; Chen, J.S.; Uysal, M. Experience quality in the different phases of a tourist vacation: A case of northern Norway. Tour. Anal. 2012, 17, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Graefe, A.R.; Burns, R.C. Examining the antecedents of destination loyalty in a forest setting. Leis. Sci. 2007, 29, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loden, M.; Rosener, J.B. Workforce America: Managing Employee Diversity as a Vital Resource; Homewood: Homewood, AL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gardenswartz, L.; Rowe, A. Diverse Teams at Work: Capitalizing on the Power of Diversity. Capitalizing on the Power of Diversity. Alexadria, VA: Society for Human Resource Management. 2003. Available online: https://researchguides.austincc.edu/c.php?g=994136&p=7261002 (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Kalargyrou, V.; W, C. Diversity Management Research in Hospitality and Tourism: Past, Present and Future. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 68–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsarn, K.; Nickpour, F. A conceptual framework for inclusive digital storytelling to increase diversity and motivation for cultural tourism in Thailand. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2016, 229, 407–415. [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur, M.; Véron, E. Ethnographie de L’exposition: L’espace, le Corps et le Sens. Réédition 1991; Bibliothèque Publique d’Information: Paris, France, 1989; ISBN 978-290-2706-198. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Dimenze Myšlení: Teorie Rozmanitých Inteligencí, 1st ed.; Portál: Praha, Czech Republic, 1999; 398 p, ISBN 80-717-8279-3. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, B.; McCarthy, D. Teaching around the 4MAT® Cycle: Designing Instruction for Diverse Learners with Diverse Learning Styles; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. The Museum Experience Revisited; Left Coast Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, J.; Garibay, C.; Wilson, K. Engaging immigrant audiences in museums. Mus. Soc. Issues 2008, 3, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L. Our home is here: History, memory, and identity in the Museum of Chinese in America. Commun. Cult. Crit. 2013, 6, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umiker-Sebeok, J. Behavior in a museum: A semio-cognitive approach to museum consumption experiences. Signifying Behav. 1994, 1, 52–100. [Google Scholar]

- D’Hudson, G.; Saling, L. Worry and rumination in older adults: Differentiating the processes. Aging Ment. Health 2010, 14, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, G.; Coles, T. Disability, holiday making and the tourism industry in the UK: A preliminary survey. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipianin-Zontek, E.; Szewczyk, I. Adaptation of Business Hotels to the Needs of Disabled Tourists in Poland. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2019, 17, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, Y.; Yayli, A.; Yesiltas, M. Is the Turkish tourism industry ready for a disabled customer’s market?: The views of hotel and travel agency managers. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butnaru, G.I.; Niţă, V.; Melinte, C.; Anichiti, A.; Brînză, G. The Nexus between Sustainable Behaviour of Tourists from Generation Z and the Factors that Influence the Protection of Environmental Quality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Keates, S.; Clarkson, P.J. Inclusive design in industry: Barriers, drivers and the business case. In Ercim Workshop on User Interfaces for All; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 305–319. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaos, B. Cultural tourism, young people and destination perception: A case study of Delphi, Greece. Dissertation, University of Exeter, 2008. Available online: https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/handle/10036/35873 (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Mayo, E.J.; Lance, P.J. The Psychology of Leisure Travel. Effective Marketing and Selling of Travel Services; CBI Publishing Company, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Fluker, M.R.; Lindsay, W.T. Needs, motivations, and expectations of a commercial whitewater rafting experience. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Bowen, J.; James, C.M.; Moreno, R.R.; Paz, M.D.R. Marketing Para Turismo; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, W.; Spence-Stone, R.; Moriarty, S.; Burnett, J. Australian Advertising Principles and Practice; Pearson Education Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mario, C.; De Santo, M.; Lombardi, M.; Mosca, R.; Santaniello, D.; Valentino, C. Recommender Systems and Digital Storytelling To Enhance Tourism Experience in Cultural Heritage Sites. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP), Irvine, CA, USA, 23–27 August 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- HEIN; Hilde, S. The Museum in Transition: A Philosophical Perspective; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tolva, J.; Martin, J. Making the transition from documentation to experience: The eternal egypt project. Arch. Mus. Inform. 2004, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kaelber, L. A memorial as virtual traumascape: Darkest tourism in 3D and cyber-space to the gas chambers of Auschwitz. Ertr E Rev. Tour. Res. 2007, 5, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Floch, J.; Jiang, S. One place, many stories digital storytelling for cultural heritage discovery in the landscape. In Proceedings of the 2015 Digital Heritage, Granada, Spain, 28 September–2 October 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Pescarin, S.; d’Annibale, E.; Fanini, B.; Ferdani, D. Prototyping on site Virtual Museums: The case study of the co-design approach to the Palatine hill in Rome (Barberini Vineyard) exhibition. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHERITAGE) held jointly with 2018 24th International Conference on Virtual Systems & Multimedia (VSMM 2018), San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–30 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G.; Christal, M. The future of virtual museums: On-line, immersive, 3d environments. Creat. Realities Group 2002, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cultraro, M.; Gabellone, F.; Scardozzi, G. The virtual musealization of archaeological sites: Between documentation and communication. In Proceedings of the 3rd ISPRS International Workshop 3D-ARCH, Trento, Italy, 25–28 February 2009; pp. 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Katifori, A.; Karvounis, M.; Kourtis, V.; Perry, S.; Roussou, M.; Ioanidis, Y. Applying interactive storytelling in cultural heritage: Opportunities, challenges and lessons learned. In Proceedings of the International conference on interactive digital storytelling, Dublin, Ireland, 5–8 December 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 603–612. [Google Scholar]

- Pujol, L.; Roussou, M.; Poulou, S.; Balet, O.; Vayanou, M.; Ioannidis, Y. Personalizing interactive digital storytelling in archaeological museums: The CHESS project. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Conference of Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology, Southampton, UK, 26–29 March 2012; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Trichopoulos, G.; Aliprantis, J.; Konstantakis, M.; Michalakis, K.; Mylonas, P.; Voutos, Y.; Caridakis, G. Augmented and personalized digital narratives for Cultural Heritage under a tangible interface. In Proceedings of the 2021 16th International Workshop on Semantic and Social Media Adaptation & Personalization (SMAP), Corfu, Greece, 4–5 November 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tzima, S.; Styliaras, G.; Bassounas, A.; Tzima, M. Harnessing the potential of storytelling and mobile technology in intangible cultural heritage: A case study in early childhood education in sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinam, M.; Ciotoli, L.; Koceva, F.; Torre, I. Digital Storytelling in a Museum Application Using the Web of Things. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Vrettakis, E.; Katifori, A.; Ioannidis, Y. Digital Storytelling and Social Interaction in Cultural Heritage-An Approach for Sites with Reduced Connectivity. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling, Tallinn, Estonia, 7–10 December 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulakis, S.; Foukarakis, M.; Tsinaraki, C.; Kanellidi, E.; Ragia, L. Contextual Geospatial Picture Understanding, Management and Visualization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Mobile Computing & Multimedia, Vienna, Austria, 2–4 December 2013; pp. 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sundstedt, V.; Chalmers, A.; Martinez, P. High fidelity reconstruction of the ancient egyptian temple of kalabsha. In Proceedings of the 3rd international conference on Computer graphics, virtual reality, visualisation and interaction in Africa, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 3–5 November 2004; pp. 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Paquet, E.; Viktor, H.L. Long-term preservation of 3-D cultural heritage data related to architectural sites. Proc. ISPRS Work. Group 2005, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rizvić, S.; Skalonjić, I. Reconstructing cultural heritage objects from storytelling. In Proceedings of the 2015 Digital Heritage, Granada, Spain, 28 September–2 October 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; Volume 2, pp. 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- CHESS—Cultural Heritage Experiences through Socio-personal interactions and Storytelling. 2011. Available online: www.chessexperience.eu (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Huiling, F.E.N.G.; Xiaoshuang, J.I.A.; Liang, N.I.U.; Lichao, L.I.U.; Yongjun, X.U. Building Digital Memory for Historic Urban Heritage: The Beijing Memory Project Experience. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHERITAGE) held jointly with 2018 24th International Conference on Virtual Systems & Multimedia (VSMM 2018), San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–30 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Garzotto, F.; Matarazzo, V.; Messina, N.; Gelsomini, M.; Riva, C. Improving museum accessibility through storytelling in wearable immersive virtual reality. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHERITAGE) held jointly with 2018 24th International Conference on Virtual Systems & Multimedia (VSMM 2018), San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–30 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Kim, J.; Bang, S.; Woo, W. The effect of applying film-induced tourism to virtual reality tours of cultural heritage sites. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHERITAGE) held jointly with 2018 24th International Conference on Virtual Systems & Multimedia (VSMM 2018), San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–30 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, M.; Gomes, J.; Gomes, C. Creating learning activities using augmented reality tools. In Proceedings of the 2nd Experiment@ International Conference—Online Experimentation, Coimbra, Portuga, 18–20 September 2013; pp. 301–305. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, F.; Figueiredo, M.; Rodrigues, J. Augmented Reality and Storytelling in heritage application in public gardens: Caloust Gulbenkian Foundation Garden. In Proceedings of the 2015 Digital Heritage, Granada, Spain, 28 September–2 October 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolakis, K.C.; Margetis, G.; Stephanidis, C. Pleistocene Crete: A narrative, interactive mixed reality exhibition that brings prehistoric wildlife back to life. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), Recife, Brazil, 9–13 November 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 237–240. [Google Scholar]

- Moumoutzis, N.; Christoulakis, M.; Xanthaki, C.; Maragoudakis, Y.; Christodoulakis, S.; Paneva-Marinova, D.; Pavlova, L. eShadow+: Mixed Reality Storytelling Inspired by Traditional Shadow Theatre. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 46th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC), Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 27 June–1 July 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 95–100. [Google Scholar]

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Peer review studies in English | Non-English studies |

| Publication in the 1990–2022 period | Publications outside the time frame were not selected |

| Journals, conference proceedings, textbooks, book chapters, and organization websites | Working papers and conference abstracts |

| Categories: Computers and Composition; Computers in Human Behavior; Design Studies; Arts and Humanities; Social Sciences | Categories: Business, Management and Accounting; Engineering; Agriculture; Economics; Econometrics and Finance |

| Database | Search Terms (Titles, Abstracts, and Keywords) 1990–2022 | Articles in CT and DST | Articles in ID and DST | Articles in CT and ID | Total (First Pass) | Total (Second Pass) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scopus (main database) | “Cultural tourism (CT) and inclusive design” (ID) or “Cultural tourism (CT) and digital storytelling” (DST) or “Inclusive design (ID) and digital storytelling” (DST) | 48 | 28 | 30 | 106 | 371 + 50 |

| ScienceDirect (main database) | 26 | 74 | 213 | 313 | ||

| Google Scholar (additional database) | 22 | 13 | 15 | 50 |

| Years | Publications | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles in CT and DST | Articles in ID and DST | Articles in CT and ID | |||||

| Scopus | ScienceDirect | Scopus | ScienceDirect | Scopus | ScienceDirect | ||

| 2022 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 17 | 51 |

| 2021 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 12 | 40 |

| 2020 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 29 |

| 2019 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 39 |

| 2018 | 7 | - | 2 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 27 |

| 2017 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 15 |

| 2016 | 1 | 3 | 4 | - | 2 | 26 | 36 |

| 2015 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 23 | 31 |

| 2014 | 2 | - | - | 4 | 1 | 21 | 28 |

| 2013 | 2 | - | 1 | 3 | 7 | 13 | |

| 2012 | - | - | 2 | - | 22 | 24 | |

| 2011 | - | - | 1 | 5 | 4 | 10 | |

| 2010 | - | - | 1 | 4 | 6 | 11 | |

| 2009 | - | 1 | - | 4 | 5 | ||

| 2008 | - | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 | ||

| 2007 | - | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||

| 2006 | 1 | 1 | - | 8 | 10 | ||

| 2005 | 1 | 1 | - | 7 | 9 | ||

| 2004 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| 2003 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 2001 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| 2000 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| 1999 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 1997 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 1996 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Keywords | Occurrences | Total Link Strength | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cultural heritage | 11 | 26 |

| 2 | Virtual reality | 10 | 23 |

| 3 | Gamification | 6 | 24 |

| 4 | Digital storytelling | 6 | 17 |

| 5 | Culture | 6 | 13 |

| 6 | Augmented reality | 5 | 16 |

| 7 | Digital rhetoric | 5 | 15 |

| 8 | Identification | 4 | 13 |

| 9 | COVID-19 | 4 | 12 |

| 10 | Digital technologies and heritage | 3 | 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kasemsarn, K.; Harrison, D.; Nickpour, F. Applying Inclusive Design and Digital Storytelling to Facilitate Cultural Tourism: A Review and Initial Framework. Heritage 2023, 6, 1411-1428. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6020077

Kasemsarn K, Harrison D, Nickpour F. Applying Inclusive Design and Digital Storytelling to Facilitate Cultural Tourism: A Review and Initial Framework. Heritage. 2023; 6(2):1411-1428. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6020077

Chicago/Turabian StyleKasemsarn, Kittichai, David Harrison, and Farnaz Nickpour. 2023. "Applying Inclusive Design and Digital Storytelling to Facilitate Cultural Tourism: A Review and Initial Framework" Heritage 6, no. 2: 1411-1428. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6020077

APA StyleKasemsarn, K., Harrison, D., & Nickpour, F. (2023). Applying Inclusive Design and Digital Storytelling to Facilitate Cultural Tourism: A Review and Initial Framework. Heritage, 6(2), 1411-1428. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6020077