A Survey on Computational and Emergent Digital Storytelling

Abstract

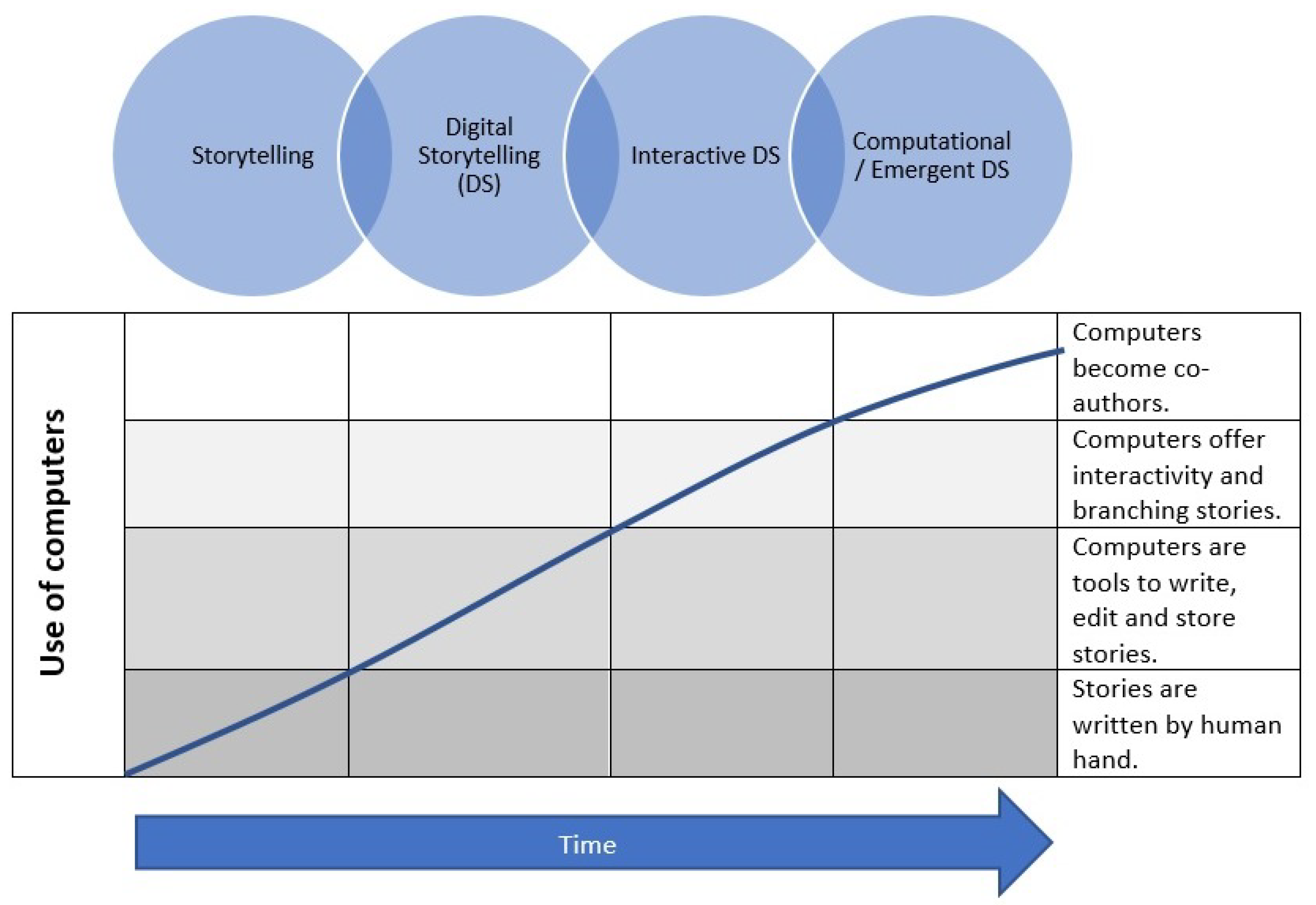

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

- DS Authoring ToolsTools specifically developed for the creation of stories are examined in this category. In this perspective, even a word processor (like Microsoft Word) may be viewed as an authoring tool, but in this survey, we focus on more complex, specialized tools that assist in the creation of stories by producing content in an automated way. Mitchell et al. [27] hosted a workshop discussion on whether authoring tools are really necessary. This is an interdisciplinary topic to discuss.

- DS Systems and ApplicationsIn this category falls mobile applications that use DS to enhance user experience, in various cases and fields of interest. There are also more complex systems, combining databases, special hardware, desktop software applications and technologies such as VR, AR, and robotic mechanisms. In either case, this category includes projects fully or partially developed, either for commercial or research purposes.

- DS Methods, Frameworks and Case StudiesThese are theoretical studies and designs for projects that use computational DS in various fields. Some of them are ongoing projects, in the middle of implementing a proof-of-concept, a demo or a complete application—system.

2.1. General Purpose Computational and Emergent Storytelling Works and Systems

2.2. In the Field of Education

2.3. In the Field of Cultural Heritage

2.4. In Games (Entertainment or Serious)

2.5. Narrative Systems in Healthcare

2.6. Newer Genres in Interactive Narrative

2.6.1. Performing Arts

2.6.2. Cinematic Interactive Narratives

2.6.3. Interactive Documentaries (iDocs)

2.6.4. Interactive News

3. Media and Interaction on Related Work

3.1. Tangible Interactive Narratives

3.2. Gesture Recognition Narrative Systems

3.3. Embodied Storytelling Systems

3.4. Mixing AR, VR, 360° Video and Animation Technologies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| DS | Digital Storytelling |

| IDS | Interactive Digital Storytelling |

| IDN | Interactive Digital Narrative |

| GPT | Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| DN | Digital Narrative |

| CDS | Computational Digital Storytelling |

| CH | Cultural Heritage |

| EM | Experience Manager |

| PW | Possible Worlds |

| MINE | Multiplayer Interactive Narrative Experience |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| NPC | Non-Player Character |

| PCG | Procedural Content Generation |

| GFI | Goals Feedback Interpretation |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| IF | Interactive Fiction |

| DGE | Data Generation Engine |

| CIN | Cinematic Interactive Narrative |

| iDoc | Interactive Documentary |

| TN | Tangible Narratives |

| UX | User Experience |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| 1 | http://tecfalabs.unige.ch/narrativeacts_vis/, accessed on 24 January 2023. |

| 2 | https://raffba.itch.io/med10, accessed on 24 January 2023. |

| 3 | https://eae-git.eng.utah.edu/01221789/utahpia2, accessed on 24 January 2023. |

| 4 | Film available on https://tilefilms.ie/productions/faoladh/, accessed on 24 January 2023. |

| 5 | https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=1HDbXisLOevXUTHFiHbBXAo7NWVxLIFo&usp=sharing, accessed on 24 January 2023. |

References

- Bedford, L. Storytelling: The Real Work of Museums. Curator Mus. J. 2001, 44, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussou, M.; Pujol, L.; Katifori, A.; Chrysanthi, A.; Perry, S.; Vayanou, M. The Museum as Digital Storyteller: Collaborative Participatory Creation of Interactive Digital Experiences. 2015. Available online: https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/the-museum-as-digital-storyteller-collaborative-participatory-creation-of-interactive-digital-experiences/index.html (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Ryan, J.O.; Mateas, M.; Wardrip-Fruin, N. Open Design Challenges for Interactive Emergent Narrative. In Proceedings of the ICIDS, Copenhagen, Denmark, 30 November–4 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C.H. Digital Storytelling: A Creator’s Guide to Interactive Entertainment; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Abas, H.; Zaman, H.B. Digital Storytelling Design with Augmented Reality Technology for Remedial Students in Learning Bahasa Melayu. Glob. Learn 2010, 2010, 3558–3563. [Google Scholar]

- Aylett, R.; Louchart, S. Being There: Participants and Spectators in Interactive Narrative. In International Conference on Virtual Storytelling. Using Virtual Reality Technologies for Storytelling; Cavazza, M., Donikian, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, E.W. Resolutions to Some Problems in Interactive Storytelling; Teeside University: Middlesborough, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin, S.; Levieux, G.; Donnart, J.Y.; Natkin, S. Making sense of emergent narratives: An architecture supporting player-triggered narrative processes. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence and Games (CIG), Tainan, Taiwan, 31 August–2 September 2015; pp. 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M.L. Possible Worlds, Artificial Intelligence, and Narrative Theory; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Szilas, N.; Marano, M.; Estupiñán, S. A Tool for Interactive Visualization of Narrative Acts. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 176–180. [Google Scholar]

- Peinado, F.; Gervás, P. Transferring Game Mastering Laws to Interactive Digital Storytelling. In International Conference on Technologies for Interactive Digital Storytelling and Entertainment; Göbel, S., Spierling, U., Hoffmann, A., Iurgel, I., Schneider, O., Dechau, J., Feix, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Spawforth, C.; Gibbins, N.; Millard, D.E. StoryMINE: A System for Multiplayer Interactive Narrative Experiences. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 534–543. [Google Scholar]

- Psomadaki, O.I.; Dimoulas, C.A.; Kalliris, G.M.; Paschalidis, G. Digital storytelling and audience engagement in cultural heritage management: A collaborative model based on the Digital City of Thessaloniki. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 36, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M. Planning in Narrative Generation: A Review of Plan-Based Approaches to the Generation of Story, Discourse and Interactivity in Narratives. Sprache Datenverarb. Spec. Issue Form. Comput. Model. Narrat. 2015, 37, 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shibolet, Y.; Knoller, N.; Koenitz, H. A Framework for Classifying and Describing Authoring Tools for Interactive Digital Narrative. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 523–533. [Google Scholar]

- Green, D.; Hargood, C.; Charles, F. Contemporary Issues in Interactive Storytelling Authoring Systems. In Proceedings of the ICIDS, Dublin, Ireland, 5–8 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Green, D. Novella: An Authoring Tool for Interactive Storytelling in Games. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 556–559. [Google Scholar]

- Kitromili, S.; Jordan, J.; Millard, D.E. How Do Writing Tools Shape Interactive Stories? In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 514–522. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, C. A Research on Storytelling of Interactive Documentary: Towards a New Storytelling Theory Model. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kybartas, B.; Bidarra, R. A Survey on Story Generation Techniques for Authoring Computational Narratives. IEEE Trans. Comput. Intell. AI Games 2017, 9, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasunic, A.; Kaufman, G.F. Learning to Listen: Critically Considering the Role of AI in Human Storytelling and Character Creation. 2018. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/W18-1501 (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Purdy, C.; Riedl, M.O. Reading Between the Lines: Using Plot Graphs to Draw Inferences from Stories. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Nack, F., Gordon, A.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Van Broeckhoven, F.; Vlieghe, J.; De Troyer, O. Using a Controlled Natural Language for Specifying the Narratives of Serious Games. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Schoenau-Fog, H., Bruni, L.E., Louchart, S., Baceviciute, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Riedl, M.O. Computational narrative intelligence: A human-centered goal for artificial intelligence. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.06484. [Google Scholar]

- Riedl, M.O.; Harrison, B. Using Stories to Teach Human Values to Artificial Agents. In Proceedings of the AAAI Workshop: AI, Ethics, and Society, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–13 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, N.; Fallenstein, B. Aligning Superintelligence with Human Interests: A Technical Research Agenda; Machine Intelligence Research Institute: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A.; Spierling, U.; Hargood, C.; Millard, D.E. Authoring for Interactive Storytelling. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 544–547. [Google Scholar]

- Vrettakis, E.; Kourtis, V.; Katifori, A.; Karvounis, M.; Lougiakis, C.; Ioannidis, Y.E. Narralive—Creating and experiencing mobile digital storytelling in cultural heritage. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2019, 15, 00114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujol, L.; Roussou, M.; Poulo, S.; Balet, O.; Vayanou, M.; Ioannidis, Y.E. Personalizing Interactive Digital Storytelling in Archaeological Museums: The CHESS Project; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Garbe, J.; Kreminski, M.; Samuel, B.; Wardrip-Fruin, N.; Mateas, M. StoryAssembler: An Engine for Generating Dynamic Choice-Driven Narratives. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games (FDG ’19), San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, 26–30 August 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Dighe, M.; Martens, C.; Jhala, A. Stories of the Town: Balancing Character Autonomy and Coherent Narrative in Procedurally Generated Worlds. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games (FDG ’19), San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, 26–30 August 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kybartas, B.; Verbrugge, C.; Lessard, J. Subject and Subjectivity: A Conversational Game Using Possible Worlds. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Nunes, N., Oakley, I., Nisi, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 332–335. [Google Scholar]

- Kreminski, M.; Dickinson, M.; Wardrip-Fruin, N. Felt: A Simple Story Sifter. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Swizerland, 2019; pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Kawagoe, S.; Ueno, M.; Isahara, H. A study on the efficiency of creating stories by the use of templates. In Proceedings of the 2015 2nd International Conference on Advanced Informatics: Concepts, Theory and Applications (ICAICTA), Chonburi, Thailand, 19–22 August 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kybartas, B.; Verbrugge, C.; Lessard, J. Expressive Range Analysis of a Possible Worlds Driven Emergent Narrative System. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 473–477. [Google Scholar]

- Guzdial, M.J.; Harrison, B.; Li, B.; Riedl, M.O. Crowdsourcing Open Interactive Narrative. In Proceedings of the FDG, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 22–25 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, K.T.; Donley, R. Using Ink and Interactive Fiction to Teach Interactive Design. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stefnisson, I.S.; Thue, D. Mimisbrunnur: AI-Assisted Authoring for Interactive Storytelling. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment (AIIDE’18), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 13–17 November; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Szilas, N.; Estupiñán, S.; Richle, U. Automatic Detection of Conflicts in Complex Narrative Structures. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 415–427. [Google Scholar]

- Hargood, C.; Weal, M.J.; Millard, D.E. The StoryPlaces Platform: Building a Web-Based Locative Hypertext System. In Proceedings of the 29th on Hypertext and Social Media (HT ’18), Baltimore, MD, USA, 9–12 July 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.; Hargood, C.; Charles, F. A Novel Design Pipeline for Authoring Tools. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Vrettakis, E.; Lougiakis, C.; Katifori, A.; Kourtis, V.; Christoforidis, S.; Karvounis, M.; Ioanidis, Y. The Story Maker—An Authoring Tool for Multimedia-Rich Interactive Narratives. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 349–352. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, A.; Kostkova, P. Interactive Digital Storytelling Based Educational Games: Formalise, Author, Play, Educate and Enjoy! —The Edugames4all Project Framework. In Transactions on Edutainment XII; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 9292, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, K.; Kybartas, B.; Mateas, M. Tracery: An Author-Focused Generative Text Tool. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Schoenau-Fog, H., Bruni, L.E., Louchart, S., Baceviciute, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 154–161. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, C.; Iqbal, O. Villanelle: An Authoring Tool for Autonomous Characters in Interactive Fiction. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 290–303. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, C.; Iqbal, O.; Azad, S.; Ingling, M.; Mosolf, A.; McCamey, E.; Timmer, J. Villanelle: Towards Authorable Autonomous Characters in Interactive Narrative. In Proceedings of the INT/WICED@AIIDE, Edmonton, AL, Canada, 13–14 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.A.; Chu, S.L.; Quek, F.; Canaday, P.; Li, Q.; Loustau, T.; Wu, S.; Zhang, L. Towards a Gesture-Based Story Authoring System: Design Implications from Feature Analysis of Iconic Gestures During Storytelling. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 364–373. [Google Scholar]

- Sanghrajka, R.; Young, R.M.; Salisbury, B.; Lang, E.W. ShowRunner: A Tool for Storyline Execution/Visualization in 3D Game Environments. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 323–327. [Google Scholar]

- Battad, Z.; White, A.; Si, M. Facilitating Information Exploration of Archival Library Materials Through Multi-modal Storytelling. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Katsui, T.; Ueno, M.; Isahara, H. A creation support system to manage the story structure based on template sets and graph. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence, 4F1-3in2, Nagoya, Japan, 30 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Katsui, T.; Ueno, M.; Isahara, H. An analysis on the process of creating stories by the creation support system. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Advanced Informatics, Concepts, Theory, and Applications (ICAICTA), Denpasar, Indonesia, 16–18 August 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Battad, Z.; Si, M. Apply Storytelling Techniques for Describing Time-Series Data. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 483–488. [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia, M.; Frey, S.; Shoulson, A.; Sumner, R.W.; Gross, M.H. CANVAS: Computer-assisted narrative animation synthesis. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Computer Animation, Zurich, Switzerland, 11–13 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alinam, M.; Ciotoli, L.; Koceva, F.; Torre, I. Digital Storytelling in a Museum Application Using the Web of Things. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cesário, V.; Olim, S.; Nisi, V. A Natural History Museum Experience: Memories of Carvalhal’s Palace—Turning Point. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Revells, T.; Chai, Y. Digital Narrative, Documents and Interactive Public History. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 361–364. [Google Scholar]

- Suckling, M. Dungeon on the Move: A Case Study of a Procedurally Driven Narrative Project in Progress. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- De Kegel, B.; Haahr, M. Towards Procedural Generation of Narrative Puzzles for Adventure Games. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, L.; Haahr, M. Honey, I’m Home: An Adventure Game with Procedurally Generated Narrative Puzzles. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- Kreminski, M.; Wardrip-Fruin, N. Throwing Bottles at God: Predictive Text as a Game Mechanic in an AI-Based Narrative Game. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 275–279. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, T.L.; Rafferty, E.I.; Schoenau-Fog, H.; Palamas, G. Embedded Narratives in Procedurally Generated Environments. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C.; Dighe, M.; Martens, C.; Jhala, A. Crafting Interactive Narrative Games with Adversarial Planning Agents from Simulations. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverri, D.; Wei, H. Letters to José: A Design Case for Building Tangible Interactive Narratives. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.C.; Lin, Y.J.; Zeng, X.; Newman, M.; O’Modhrain, S. Olegoru: A Soundscape Composition Tool to Enhance Imaginative Storytelling with Tangible Objects. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (TEI ’15), Stanford, CA, USA, 15–19 January 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, S.; Snow, S.; Jennings, K.; Rose, B.; Matthews, B.; Viller, S. Vim: A Tangible Energy Story. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.; Chang, J.; Kazmi, I.K.; Zhang, J.J.; Jiao, P. Hand gesture-based interactive puppetry system to assist storytelling for children. Vis. Comput. 2017, 33, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicke, P.; Veale, T. Wheels Within Wheels: A Causal Treatment of Image Schemas in An Embodied Storytelling System. In Proceedings of the TriCoLore, Bozen-Bolzano, Italy, 13–15 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga, S.; Seaborn, K.; Tamura, K.; Otake-Matsuura, M. Cognitive Training for Older Adults with a Dialogue-Based, Robot-Facilitated Storytelling System. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 405–409. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, A. Creating a Virtual Support Group in an Interactive Narrative: A Companionship Game for Cancer Patients. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 662–665. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, T. Using VR to Simulate Interactable AR Storytelling. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 328–332. [Google Scholar]

- Vosmeer, M.; Sandovar, A.; Schouten, B. From Literary Novel to Radio Drama to VR Project. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 392–400. [Google Scholar]

- Green, C.P.; Holmquist, L.E.; Gibson, S. Towards the Emergent Theatre: A Novel Approach for Creating Live Emergent Narratives Using Finite State Machines. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, B.R.; Winer, D.R.; Barot, C.; Young, R.M. Firebolt: A System for Automated Low-Level Cinematic Narrative Realization. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, D.; Fearghail, C.O.; Smolic, A.; Knorr, S. Faoladh: A Case Study in Cinematic VR Storytelling and Production. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 359–362. [Google Scholar]

- Basaraba, N.; Conlan, O.; Edmond, J.; Arnds, P. User Testing Persuasive Interactive Web Documentaries: An Empirical Study. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bala, P.; Dionisio, M.; Andrade, T.; Nisi, V. Tell a Tail 360: Immersive Storytelling on Animal Welfare. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 357–360. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, T.; Holloway-Attaway, L.; Beroldy, E. Leaving the Small Screen: Telling News Stories in a VR Simulation of an AR News Service. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 352–355. [Google Scholar]

- Stavrakakis, N. Live News Visualization on the Map of Greece. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L.J.; Harrison, B.; Riedl, M.O. Improvisational Computational Storytelling in Open Worlds. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Nack, F., Gordon, A.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Berov, L. A Character Focused Iterative Simulation Approach to Computational Storytelling. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 494–497. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenau-Fog, H. Adaptive storyworlds. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Womack, J.; Freeman, W. Interactive Narrative Generation Using Location and Genre Specific Context. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 343–347. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J. The Book of Endless History: Authorial Use of GPT2 for Interactive Storytelling. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 429–432. [Google Scholar]

- Kreminski, M.; Wardrip-Fruin, N. Sketching a Map of the Storylets Design Space. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 160–164. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L.J.; Ammanabrolu, P.; Wang, X.; Hancock, W.; Singh, S.; Harrison, B.; Riedl, M.O. Event Representations for Automated Story Generation with Deep Neural Nets. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Thirtieth Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference and Eighth AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence (AAAI’18/IAAI’18/EAAI’18), New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Amos-Binks, A.; Potts, C.; Young, R. Planning Graphs for Efficient Generation of Desirable Narrative Trajectories. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. Interact. Digit. Entertain. 2021, 13, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Hargood, C.; Tang, W.; Charles, F. Towards Generating Stylistic Dialogues for Narratives Using Data-Driven Approaches. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 462–472. [Google Scholar]

- Short, E. Beyond branching: Quality-based, salience-based, and waypoint narrative structures. Available online: https://emshort.blog/2016/04/12/beyond-branching-quality-based-and-salience-based-narrative-structures/ (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Koenitz, H.; Dubbelman, T.; Knoller, N.; Roth, C.; Haahr, M.; Sezen, D.; Sezen, T.I. Card-Based Methods in Interactive Narrative Prototyping. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 552–555. [Google Scholar]

- Koenitz, H.; Dubbelman, T.; Roth, C. An Educational Program in Interactive Narrative Design. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, M.; Palosaari Eladhari, M.; Koenitz, H.; Louchart, S.; Nack, F.; Martens, C.; Rossi, G.C.; Bosser, A.G.; Millard, D.E. ICIDS2020 Panel: Building the Discipline of Interactive Digital Narratives. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton, C.C.; Warren, A.E.; Archambault, L.M. Exploring the Use of Interactive Digital Storytelling Video: Promoting Student Engagement and Learning in a University Hybrid Course. TechTrends 2016, 60, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvic, S.; Boskovic, D.; Okanovic, V.; Sljivo, S.; Zukic, M. Interactive digital storytelling: Bringing cultural heritage in a classroom. J. Comput. Educ. 2019, 6, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Mott, B.; Taylor, S.; Hubbard-Cheuoua, A.; Minogue, J.; Oliver, K.; Ringstaff, C. Toward a Block-Based Programming Approach to Interactive Storytelling for Upper Elementary Students. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Rizvic, S.; Djapo, N.; Alispahic, F.; Hadzihalilovic, B.; Cengic, F.F.; Imamovic, A.; Okanovic, V.; Boskovic, D. Guidelines for interactive digital storytelling presentations of cultural heritage. In Proceedings of the 2017 9th International Conference on Virtual Worlds and Games for Serious Applications (VS-Games), Athens, Greece, 6–8 September 2017; pp. 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, R. Partners: Human and Nonhuman Performers and Interactive Narrative in Postdigital Theater. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 369–382. [Google Scholar]

- Strugnell, J.; Berry, M.; Zambetta, F.; Greuter, S. Narrative Improvisation: Simulating Game Master Choices. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 428–441. [Google Scholar]

- Kawano, Y.; Takaya, E.; Yamanobe, K.; Kurihara, S. Automatic Plot Generation Framework for Scenario Creation. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 453–461. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, J.; Young, R.M. Automated Gameplay Generation from Declarative World Representations. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. Interact. Digit. Entertain. 2021, 11, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spawforth, C.; Millard, D.E. A Framework for Multi-participant Narratives Based on Multiplayer Game Interactions. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Nunes, N., Oakley, I., Nisi, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 150–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona-Rivera, R.E.; Zagal, J.P.; Debus, M.S. GFI: A Formal Approach to Narrative Design and Game Research. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Bosser, A.G., Millard, D.E., Hargood, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, J.H. Designing Tangible Interfaces to Support Expression and Sensemaking in Interactive Narratives. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Stanford, CA, USA, 15–19 January 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, J.H.; Mazalek, A. Embodied Engagement with Narrative: A Design Framework for Presenting Cultural Heritage Artifacts. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2019, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.L.; Quek, F.; Sridharamurthy, K. Augmenting Children’s Creative Self-Efficacy and Performance through Enactment-Based Animated Storytelling. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (TEI ’15), Stanford, CA, USA, 15–19 January 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradeda, R.; Ferreira, M.J.; Martinho, C.; Paiva, A. Communicating Assertiveness in Robotic Storytellers. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 442–452. [Google Scholar]

- Paradeda, R.; Ferreira, M.J.; Martinho, C.; Paiva, A. Would You Follow the Suggestions of a Storyteller Robot? In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 489–493. [Google Scholar]

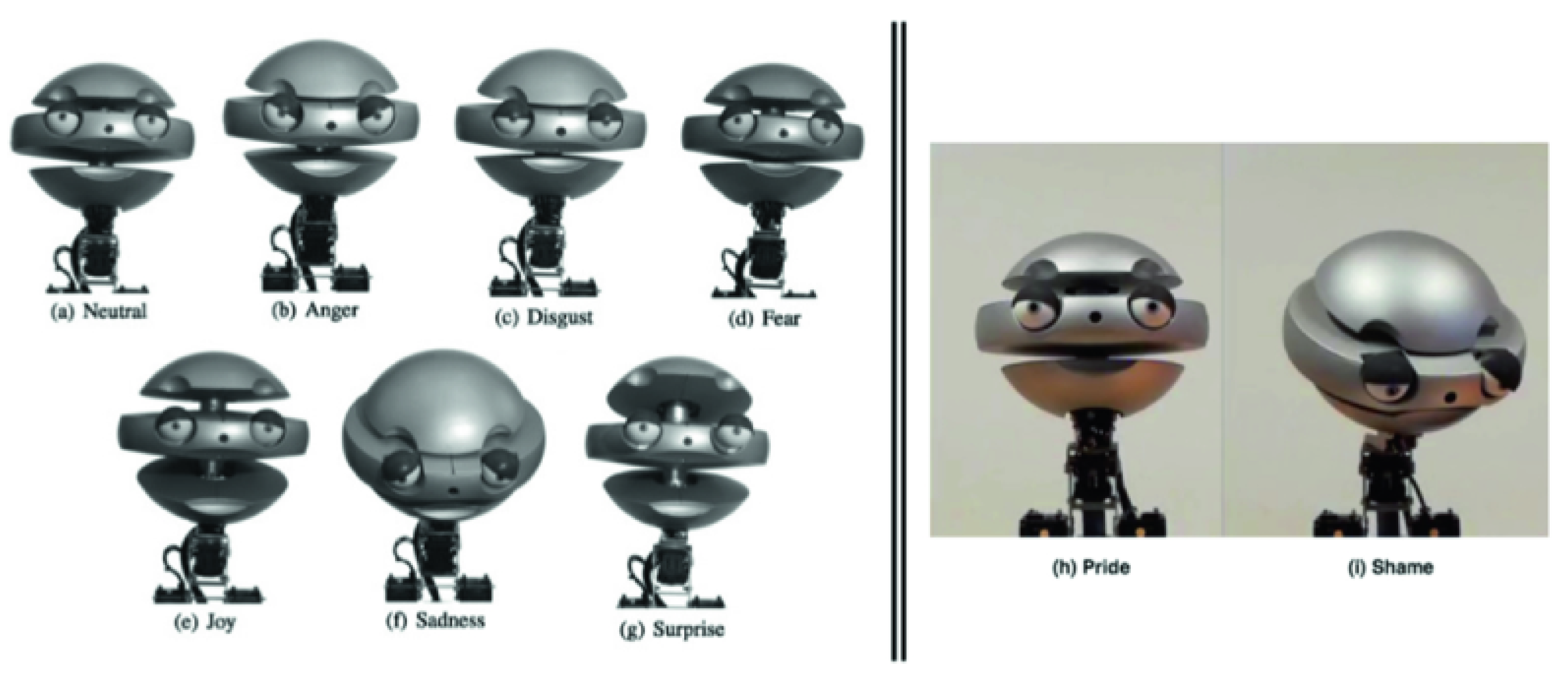

- Striepe, H.; Lugrin, B. There Once Was a Robot Storyteller: Measuring the Effects of Emotion and Non-verbal Behaviour. In International Conference on Social Robotics; Kheddar, A., Yoshida, E., Ge, S.S., Suzuki, K., Cabibihan, J.J., Eyssel, F., He, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Ozaeta, L.; Graña, M. On Intelligent Systems for Storytelling. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference SOCO’18-CISIS’18-ICEUTE’18, San Sebastian, Spain, 6–8 June 2018; Graña, M., López-Guede, J.M., Etxaniz, O., Herrero, Á., Sáez, J.A., Quintián, H., Corchado, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 571–578. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, D.u.; Ryu, H.; Kim, J. Making New Narrative Structures with Actor’s Eye-Contact in Cinematic Virtual Reality (CVR). In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 343–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kampa, A. Authoring Concepts and Tools for Interactive Digital Storytelling in the Field of Mobile Augmented Reality. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Nunes, N., Oakley, I., Nisi, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 372–375. [Google Scholar]

- Bhide, S.; Goins, E.; Geigel, J. Experimental Analysis of Spatial Sound for Storytelling in Virtual Reality. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, D. fanSHEN’s Looking for Love: A Case Study in How Theatrical and Performative Practices Inform Interactive Digital Narratives. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 401–407. [Google Scholar]

- Schalk, S. Vox Populi. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 408–411. [Google Scholar]

- Vosmeer, M.; Schouten, B. Project Orpheus A Research Study into 360° Cinematic VR. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video (TVX ’17), Hilversum, The Netherlands, 14–16 June 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, J.S.; Verma, M. Grammar of VR Storytelling: Narrative Immersion and Experiential Fidelity in VR Cinema. In Proceedings of the The 17th International Conference on Virtual-Reality Continuum and Its Applications in Industry (VRCAI ’19), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 14–16 November 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thue, D.; Schiffel, S.; Árnason, R.A.; Stefnisson, I.S.; Steinarsson, B. Delayed Roles with Authorable Continuity in Plan-Based Interactive Storytelling. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Nack, F., Gordon, A.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 258–269. [Google Scholar]

- Thue, D.; Schiffel, S.; Guethmundsson, T.P.; Kristjánsson, G.F.; Eiríksson, K.; Björnsson, M.V. Open World Story Generation for Increased Expressive Range. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Nunes, N., Oakley, I., Nisi, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 313–316. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training. 2018. Available online: https://openai.com/blog/language-unsupervised/ (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenau-Fog, H.; Larsen, B.A. Creating Interactive Adaptive Real Time Story Worlds. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 548–551. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Lee-Urban, S.; Johnston, G.; Riedl, M.O. Story Generation with Crowdsourced Plot Graphs. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI’13); AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 598–604. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, A. The effect of interactive digital storytelling gamification on microbiology classroom interactions. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Integrated STEM Education Conference (ISEC), Princeton, NJ, USA, 10 March 2018; pp. 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, R. Someone Else’s Story: An Ethical Approach to Interactive Narrative Design for Cultural Heritage. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Cardona-Rivera, R.E., Sullivan, A., Young, R.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Vayanou, M.; Katifori, A.; Karvounis, M.; Kourtis, V.; Kyriakidi, M.; Roussou, M.; Tsangaris, M.; Ioannidis, Y.; Balet, O.; Prados, T.; et al. Authoring Personalized Interactive Museum Stories. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Mitchell, A., Fernández-Vara, C., Thue, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Roussou, M.; Ripanti, F.; Servi, K. Engaging visitors of archaeological sites through ‘emotive’ storytelling experiences: A pilot at the Ancient Agora of Athens. Archeol. Calc. 2017, 28, 405–420. [Google Scholar]

- De Kegel, B.; Haahr, M. Procedural Puzzle Generation: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Games 2020, 12, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbet, M.G.; Orth, M.; Ishii, H. Triangles: Tangible interface for manipulation and exploration of digital information topography. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 18–23 April 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Catala, A.; Theune, M.; Sylla, C.; Ribeiro, P. Bringing Together Interactive Digital Storytelling with Tangible Interaction: Challenges and Opportunities. In International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling; Nunes, N., Oakley, I., Nisi, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 395–398. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shamayleh, A.S.; Ahmad, R.B.; Abushariah, M.A.A.M.; Alam, K.A.; Jomhari, N. A systematic literature review on vision based gesture recognition techniques. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2018, 77, 28121–28184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautaray, S.S.; Agrawal, A. Vision based hand gesture recognition for human computer interaction: A survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2015, 43, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicke, P.; Veale, T. Storytelling by a Show of Hands: A Framework for Interactive Embodied Storytelling in Robotic Agents. 2018. Available online: http://haddock.ucd.ie/Papers/AISB18-Wicke-Veale.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Wicke, P.; Veale, T. Interview with the Robot: Question-Guided Collaboration in a Storytelling System. In Proceedings of the ICCC, Chengdu, China, 7–10 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Caić, M.; Mahr, D.; Oderkerken-Schröder, G. Value of social robots in services: Social cognition perspective. J. Serv. Mark. 2019, 33, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradeda, R.B.; Martinho, C.; Paiva, A. Persuasion Based on Personality Traits: Using a Social Robot as Storyteller. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2017 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI ’17), Vienna, Austria, 6–9 March 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Conference |

|---|---|

| 1 | International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling (ICIDS) |

| 2 | ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media (HT) |

| 3 | International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques (SIGGRAPH) |

| 4 | International Conference on Advanced Informatics Concepts Theory and Applications (ICAICTA) |

| 5 | Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment (AIIDE) |

| 6 | Annual Conference of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence (JSAI), AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI) |

| 7 | Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference (IAAI) |

| 8 | ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) |

| 9 | International Conference on Soft Computing Models in Industrial and Environmental Applications (SOCO) |

| 10 | International Conference on Technologies for Interactive Digital Storytelling and Entertainment (TIDSE) |

| 11 | International Conference on Social Robotics (ICSR) |

| 12 | International Conference on Virtual Reality Continuum and its Applications in Industry (VRCAI) |

| 13 | International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video (TVX) |

| 14 | IEEE Integrated STEM Education Conference (ISEC) |

| 15 | International Conference on Virtual Worlds and Games for Serious Applications (VS-Games) |

| 16 | Conference on Tangible and Embedded Interaction (TEI) |

| 17 | Foundations of Digital Games Conference (FDG) |

| No | Work Title/Authors | Category | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS Authoring Tool | DS System/ Application | Method/ Framework/ Case Study | ||

| 1 | Kawagoe S. et al. [34] | √ | ||

| 2 | Kybartas B. et al. [35] | √ | ||

| 3 | Subject and Subjectivity [32] | √ | √ | |

| 4 | Scheherazade-IF [36] | √ | ||

| 5 | Ink [37] | √ | ||

| 6 | Mimisbrunnur [38] | √ | ||

| 7 | Szilas N. et al. [39] | √ | ||

| 8 | StoryPlaces [40] | √ | ||

| 9 | Green D. et al. [41] | √ | ||

| 10 | Pujol et al. [29] | √ | √ | |

| 11 | The Story Maker [42] | √ | ||

| 12 | Narralive [28] | √ | √ | |

| 13 | Molnar A. et al. [43] | √ | ||

| 14 | Tracery [44] | √ | ||

| 15 | Villanelle [45,46] | √ | ||

| 16 | Novella [17] | √ | ||

| 17 | Brown S. et al. [47] | √ | ||

| 18 | ShowRunner [48] | √ | ||

| 19 | Battad Z. et al. [49] | √ | ||

| 20 | Felt [33] | √ | √ | |

| 21 | Katsui T. et al. [50,51] | √ | ||

| 22 | Battad Z. et al. [52] | √ | ||

| 23 | CANVAS [53] | √ | ||

| 24 | StoryAssembler [30] | √ | √ | |

| 25 | Stories of the town [31] | √ | √ | |

| 26 | WoTEdu [54] | √ | ||

| 27 | Turning Point [55] | √ | ||

| 28 | Revells and Chai [56] | √ | ||

| 29 | M.Suckling [57] | √ | ||

| 30 | De Kegel B. et al. [58] | √ | ||

| 31 | Honey I’m Home [59] | √ | ||

| 32 | Throwing Bottles at God [60] | √ | ||

| 33 | storyMINE [12] | √ | ||

| 34 | Nielsen T.L. et al. [61] | √ | ||

| 35 | Adversario [62] | √ | ||

| 36 | Letters to José [63] | √ | ||

| 37 | Olegoru [64] | √ | ||

| 38 | Vim [65] | √ | ||

| 39 | Liang H. et al. [66] | √ | ||

| 40 | Wicke P. et al. [67] | √ | ||

| 41 | Tokunaga et al. [68] | √ | ||

| 42 | Bowman A. [69] | √ | ||

| 43 | Svensson T. [70] | √ | ||

| 44 | The thousand autumns of Jacob de Zoet [71] | √ | ||

| 45 | Green C.P. et al. [72] | √ | ||

| 46 | Firebolt [73] | √ | ||

| 47 | Faoladh [74] | √ | ||

| 48 | Basaraba N. et al. [75] | √ | ||

| 49 | Tell a Tail 360° [76] | √ | ||

| 50 | Svensson T. et al. [77] | √ | ||

| 51 | Stavrakakis N. [78] | √ | ||

| 52 | Martin L.J. et al. [79] | √ | ||

| 53 | Leonid Berov [80] | √ | ||

| 54 | Chauvin S. et al. [8] | √ | ||

| 55 | Carolyn Miller [4] | √ | ||

| 56 | Schoenau-Fog H. [81] | √ | ||

| 57 | Womack and Freeman [82] | √ | ||

| 58 | Austin J. [83] | √ | ||

| 59 | Kreminski M. et al. [84] | √ | ||

| 60 | Szilas N. et al. [39] | √ | ||

| 61 | Martin L. et al. [85] | √ | ||

| 62 | Amos-Binks A. et al. [86] | √ | ||

| 63 | Xu W. et al. [87] | √ | ||

| 64 | Short E. [88] | √ | ||

| 65 | Koenitz H. et al. [89] | √ | ||

| 66 | Koenitz H. et al. [90] | √ | ||

| 67 | Bernstein M. et al. [91] | √ | ||

| 68 | Shelton et al. [92] | √ | ||

| 69 | Rizvic S. et al. [93] | √ | ||

| 70 | Smith A. et al. [94] | √ | ||

| 71 | Rizvic S. et al. [95] | √ | ||

| 72 | Rouse R. [96] | √ | ||

| 73 | Strugnell J. et al. [97] | √ | ||

| 74 | Kawano Y. et al. [98] | √ | ||

| 75 | Robertson J. et al. [99] | √ | ||

| 76 | Spawforth C. et al. [100] | √ | ||

| 77 | Cardona-Rivera R.E. et al. [101] | √ | ||

| 78 | Chu J. [102] | √ | ||

| 79 | Mapping Place [103] | √ | ||

| 80 | Chu S. at al. [104] | √ | ||

| 81 | Paradeda R. et al. [105] | √ | ||

| 82 | Paradeda R. et al. [106] | √ | ||

| 83 | Striepe and Lugrin [107] | √ | ||

| 84 | Ozaeta and Graña [108] | √ | ||

| 85 | Ko et al. [109] | √ | ||

| 86 | Kampa A. [110] | √ | ||

| 87 | Bhide S. et al. [111] | √ | ||

| 88 | fanSHEN [112] | √ | ||

| 89 | Vox Populi [113] | √ | ||

| 90 | Project Orpheus [114] | √ | ||

| 91 | Pillai J. and Verma M. [115] | √ | ||

| 92 | Mu C. [19] | √ | ||

| No | Work Title/Authors | Education | Cultural Heritage | Games | Healthcare | Newer Genres of IDN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performing Arts | Cinematic IN | iDocs | Interactive News | General Purpose | ||||||

| 1 | Koenitz H. et al. [90] | √ | ||||||||

| 2 | Bernstein M. et al. [91] | √ | ||||||||

| 3 | C.C. Shelton [92] | √ | ||||||||

| 4 | Rizvic S. et al. [93] | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 5 | Smith A. et al. [94] | √ | ||||||||

| 6 | Olegoru [64] | √ | ||||||||

| 7 | Chu S. at al. [104] | √ | ||||||||

| 8 | Vim [65] | √ | ||||||||

| 9 | Liang H. et al. [66] | √ | ||||||||

| 10 | Ozaeta L. and Graña M. [108] | √ | ||||||||

| 11 | Mapping Place [103] | √ | ||||||||

| 12 | Svensson T. [70] | √ | ||||||||

| 13 | Rizvic S. et al. [95] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 14 | Roussou et al. [2] | √ | ||||||||

| 15 | Rouse R. [123] | √ | ||||||||

| 16 | WoTEdu [54] | √ | ||||||||

| 17 | Turning Point [55] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 18 | The Story Maker [42] | √ | ||||||||

| 19 | Revells T. et al. [56] | √ | ||||||||

| 20 | Narralive [28] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 21 | Letters to José [63] | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 22 | Chu J. [102] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 23 | Molnar A. et al. [43] | √ | ||||||||

| 24 | M.Suckling [57] | √ | ||||||||

| 25 | De Kegel B. et al. [58] | √ | ||||||||

| 26 | Honey I’m Home [59] | √ | ||||||||

| 27 | Throwing Bottles at God [60] | √ | ||||||||

| 28 | Tracery [44] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 29 | Strugnell J. et al. [97] | √ | ||||||||

| 30 | Kawano Y. et al. [98] | √ | ||||||||

| 31 | Robertson J. et al. [99] | √ | ||||||||

| 32 | storyMINE [12] | √ | ||||||||

| 33 | Spawforth C. et al. [100] | √ | ||||||||

| 34 | Nielsen T.L. et al. [61] | √ | ||||||||

| 35 | Adversario [62] | √ | ||||||||

| 36 | Cardona-Rivera R.E. et al. [101] | √ | ||||||||

| 37 | Villanelle [45,46] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 38 | Novella [17] | √ | ||||||||

| 39 | Bhide S. et al. [111] | √ | ||||||||

| 40 | Paradeda R. et al. [105] | √ | ||||||||

| 41 | Tokunaga et al. [68] | √ | ||||||||

| 42 | Bowman A. [69] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 43 | fanSHEN [112] | √ | ||||||||

| 44 | Vox Populi [113] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 45 | Green C.P. et al. [72] | √ | ||||||||

| 46 | The thousand autumns of Jacob de Zoet [71] | √ | ||||||||

| 47 | Ko et al. [109] | √ | ||||||||

| 48 | Kampa A. [110] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 49 | ShowRunner [48] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 50 | Firebolt [73] | √ | ||||||||

| 51 | Faoladh [74] | √ | ||||||||

| 52 | Project Orpheus [114] | √ | ||||||||

| 53 | Pillai J. and Verma M. [115] | √ | ||||||||

| 54 | Mu C. [19] | √ | ||||||||

| 55 | Basaraba N. et al. [75] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 56 | Tell a Tail 360° [76] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 57 | Svensson T. et al. [77] | √ | ||||||||

| 58 | Stavrakakis N. [78] | √ | ||||||||

| 59 | Martin L.J. et al. [79] | √ | ||||||||

| 60 | Leonid Berov [80] | √ | ||||||||

| 61 | Chauvin S. et al. [8] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 62 | Carolyn Miller [4] | √ | ||||||||

| 63 | Battad Z. et al. [49] | √ | ||||||||

| 64 | Felt [33] | √ | ||||||||

| 65 | Schoenau-Fog H. [81] | √ | ||||||||

| 66 | Womack and Freeman [82] | √ | ||||||||

| 67 | Austin J. [83] | √ | ||||||||

| 68 | Kreminski M. et al. [84] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 69 | Szilas N. et al. [39] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 70 | Martin L. et al. [85] | √ | ||||||||

| 71 | Amos-Binks A. et al. [86] | √ | ||||||||

| 72 | Katsui T. et al. [50,51] | √ | ||||||||

| 73 | Xu W. et al. [87] | √ | ||||||||

| 74 | Battad Z. et al. [52] | √ | ||||||||

| 75 | Short E. [88] | √ | ||||||||

| 76 | Koenitz H. et al. [89] | √ | ||||||||

| 77 | CANVAS [53] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 78 | StoryAssembler [30] | √ | ||||||||

| 79 | Stories of the town [31] | √ | ||||||||

| 80 | Kawagoe S. et al. [34] | √ | ||||||||

| 81 | Kybartas B. et al. [35] | √ | ||||||||

| 82 | Subject and Subjectivity [32] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 83 | Scheherazade-IF [36] | √ | ||||||||

| 84 | Ink [37] | √ | ||||||||

| 85 | Mimisbrunnur [38] | √ | ||||||||

| 86 | Szilas N. et al. [10] | √ | ||||||||

| 87 | StoryPlaces [40] | √ | ||||||||

| 88 | Green D. et al. [41] | √ | ||||||||

| 89 | Paradeda R. et al. [106] | √ | √ | |||||||

| 90 | Striepe H. and Lugrin B. [107] | √ | ||||||||

| 91 | Brown S. et al. [47] | √ | ||||||||

| 92 | Wicke P. et al. [67] | √ | ||||||||

| No | Work Title/Authors | Tangible IDN | Gesture Recognition | Embodied DS | VR/AR/360° Video/Animation | Interaction/UX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Koenitz H. et al. [89] | √ | Cards | |||

| 2 | Letters to José [63] | √ | Paper objects | |||

| 3 | Chu J. [102] | √ | Special objects | |||

| 4 | Mapping Place [103] | √ | Embodied replicas | |||

| 5 | Olegoru [64] | √ | Special objects | |||

| 6 | Chu S. at al. [104] | √ | Special objects | |||

| 7 | Vim [65] | √ | Complex construction | |||

| 8 | Brown S. et al. [47] | √ | Hand gestures | |||

| 9 | Liang H. et al. [66] | √ | Hand gestures | |||

| 10 | Wicke P. et al. [67] | √ | √ | Hand gestures | ||

| 11 | Paradeda R. et al. [105] | √ | Robot | |||

| 12 | Paradeda R. et al. [106] | √ | Robot | |||

| 13 | Striepe H. and Lugrin B. [107] | √ | Robot | |||

| 14 | Ozaeta L. and Graña M. [108] | √ | Robot | |||

| 15 | Tokunaga et al. [68] | √ | Robot | |||

| 16 | CANVAS [53] | √ | Computer animation and sound | |||

| 17 | Rouse R. [123] | √ | Augmented Reality | |||

| 18 | Revells T. et al. [56] | √ | Virtual Reality | |||

| 19 | Carolyn Miller [4] | √ | AR, VR and mixed reality | |||

| 20 | Svensson T. [70] | √ | VR and AR | |||

| 21 | Ko et al. [109] | √ | 360° Video and VR | |||

| 22 | Kampa A. [110] | √ | Mobile app with AR | |||

| 23 | Bhide S. et al. [111] | √ | VR and Spacial sound | |||

| 24 | The thousand autumns of Jacob de Zoet [71] | √ | Sound recordings and VR | |||

| 25 | Firebolt [73] | √ | Animation and Video | |||

| 26 | Project Orpheus [114] | √ | 360° Video and VR | |||

| 27 | Pillai J. and Verma M. [115] | √ | Cinematic VR | |||

| 28 | Mu C. [19] | √ | Interactive Video | |||

| 29 | Tell a Tail 360° [76] | √ | 360° Video | |||

| 30 | Svensson T. et al. [77] | √ | VR and AR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trichopoulos, G.; Alexandridis, G.; Caridakis, G. A Survey on Computational and Emergent Digital Storytelling. Heritage 2023, 6, 1227-1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6020068

Trichopoulos G, Alexandridis G, Caridakis G. A Survey on Computational and Emergent Digital Storytelling. Heritage. 2023; 6(2):1227-1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6020068

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrichopoulos, Georgios, Georgios Alexandridis, and George Caridakis. 2023. "A Survey on Computational and Emergent Digital Storytelling" Heritage 6, no. 2: 1227-1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6020068

APA StyleTrichopoulos, G., Alexandridis, G., & Caridakis, G. (2023). A Survey on Computational and Emergent Digital Storytelling. Heritage, 6(2), 1227-1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6020068