4.1. Three Unique Spaces

As we already know from our previous research, the residential areas of greatest wealth were located in the quarters of Santa María la Mayor and Santa Cruz, surrounding the Cathedral and the Real Alcázar of Seville (

Figure 4). The ownership of most of the houses in the area of Abades Street and Las Gradas Street was in the hands of the Cathedral chapter (more than 1140 apeos and written descriptive records of the cathedral and some charitable hospitals have been consulted in the Archive of the Cathedral of Seville ACS- [

30] (section II, book 9163, year 1542 and book 9717, year 1543)- and in the Archive of Diputación Provincial of Seville ADPS Cinco Llagas Hospital- [

33] (book 1, 16th Century); Cardenal Hospital, Book 3, year 1580; Bubas Hospital, Book 3-bis, year 1585). On the other hand, although the Chapter also owned a good part of the houses of the old Jewish quarter, the majority of its buildings were owned by certain nobles [

36,

37]. Therefore, a large number of Seville’s main houses were leased to high-ranking church officials or wealthy Converso families. These Converso families had had to part with their properties in the past and remained living in their houses, paying rent for life.

The fact of living in these areas of the city was already a reason for pride and social prestige. If, in addition, the house had a large surface area, with many patios and richly ornamented rooms, it offered the visitor an appearance of high purchasing power and social rank. The desire to belong and have wealth (even if it was only a mirage) was materialized in the number of patios, reception rooms (recibimientos), stables, main rooms, women’s quarters (servicios de mujeres), their own ovens, gardens, and orchards that were part of the layout of the house.

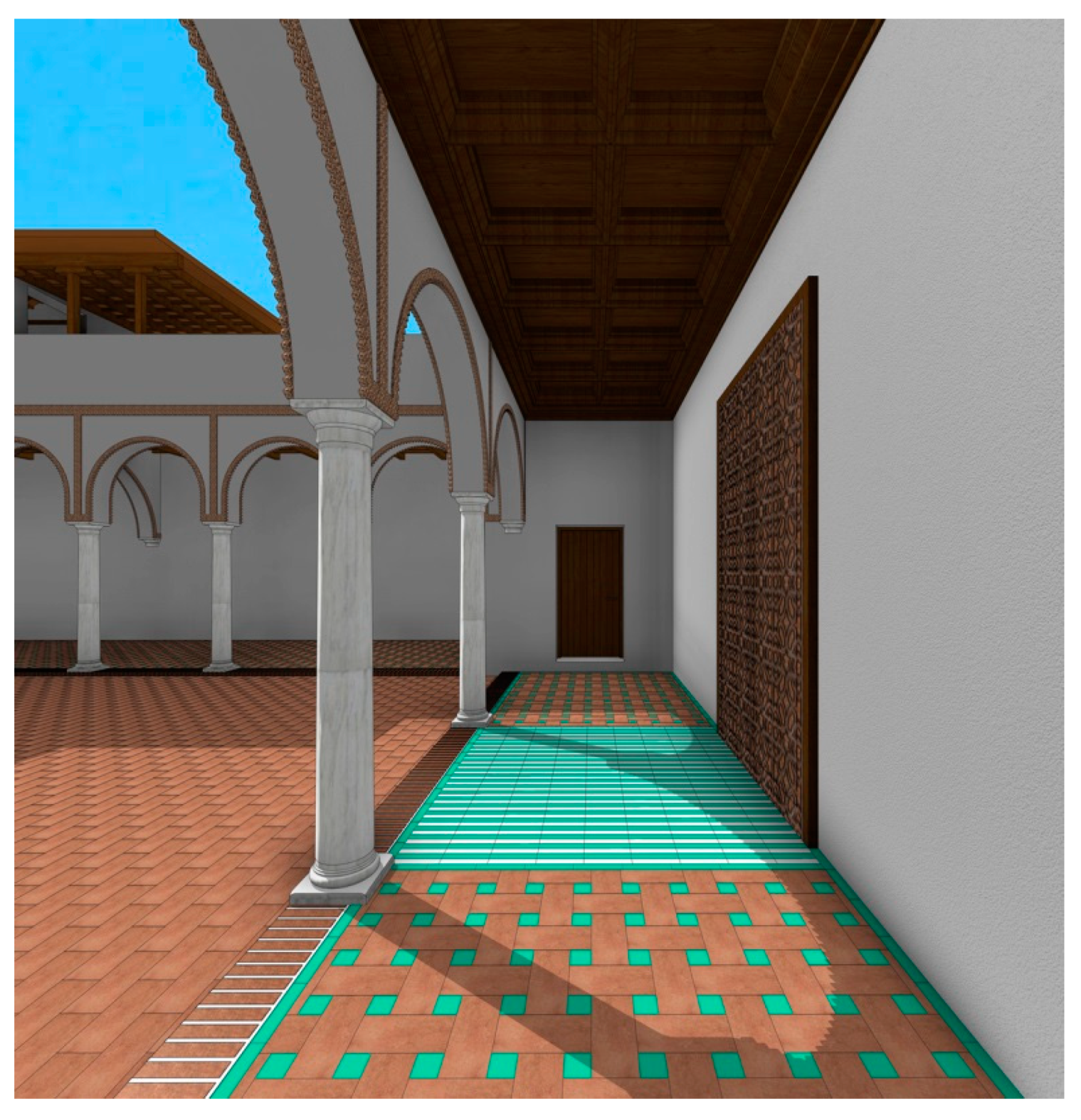

It is well known that the main space of the Sevillian house was the patio. The greater the number and surface area of patios, the greater the wealth of its inhabitants. For this reason, the appearance of the main courtyard was very well cared for, and it was usually decorated, with the presence of portals on at least three of its sides, with a series of arches (danzas de arcos) (with plasterwork) and marble columns; it was like a performance space.

But the main patios were not the only spaces that embodied the grandeur of the family that inhabited the house. There were other characteristic spaces in the Sevillian house, among which we would highlight the reception courtyards (recibimientos) or entry halls, the main rooms, and the women’s quarters (servicios de mujeres).

In the specific case of the Converso houses, the former spaces were more important as a way of demonstrating ambition and the intention to fit into Sevillian society through ostentation. Thus, the latter were the intimate spaces where the forbidden religion was practiced without fear of being discovered. Perhaps they could help to understand better the reflection of emotions in the architecture of the Converso houses, which, in our opinion, can be extrapolated to all 16th Century Sevillian houses.

4.1.1. Recibimientos

The reception areas (recibimientos) were patios near the entrances of the houses that separated the outside from the intimacy of the house and served to receive visitors (who usually came on horseback). For this reason, this space that sometimes was used as a casapuerta had an associated stable. In addition, it had stalls and a mezzanine for the grooms to sleep and store the straw. The Cruces 2 house had one that was adjacent to the casapuerta-portal and stood out because it had several windows facing it. Additionally, it is distinguished by its above-average dimensions and by being disproportionate to the rest of the house. This reception room was designed to amaze the visitor; it had a stable on the right, two portals with arches and brick octagonal pillars, a chamber (probably to give shelter to the grooms), and an alley (

Figure 17).

Between the Cathedral and the Charity Hospitals apeos and written descriptive records (1140 apeos of houses), 42 recibimientos have been identified. To these should be added some patios that had the same function although they were not included under this denomination. Some main courtyards had the same function and layout. In their porticoes, the arch series (danzas de arcos) with plasterwork was very common, with marble columns or brick octagonal pillars. Further, their floors were also very elaborate, usually with almatrayas, azonales, and olambrillas at the entrance of the main rooms and portals.

By analyzing the reception spaces identified as such, we can reach several conclusions, offering concrete examples based on the descriptions from the apeos. In the first place, these spaces do not always appear in large houses since there are eight exceptions, all related to commercial activity (three in Placentines and Francos Streets, one in Las Gradas, three in Carretería and one in Sierpe Street) [

30] (section II, book 9163, year 1542, sheets 131r, 140v, 159r, 163v, 380r, 380v, 382r and 398r). Secondly, the houses of the Cathedral were not the only ones that had these open spaces; the houses of the Cardinal, the Bubas, and the Cinco Llagas Hospitals (spread throughout the city), also had them.

As for their spatial composition, all of them were uncovered, and most of them were on the ground floor (only one on the first floor, called high recibimiento, which fell towards the portals of the Gradas Street). In addition, that space used to have a brick floor, as in the case of the Cruces 2 house. Moreover, there were windows in its walls that looked out from the chambers, both low and high, and balconies. In most cases it had, at least, a doorway, and it was accessed from the casapuerta, a vestibule or closed doorway.

Finally, it usually had a staircase, stables, and sometimes direct access to the women’s quarter (servicio de mujeres). This was the case in the house in Guzmán el Bueno. This house had a casapuerta, stables, a reception area, and a servicio de mujeres with its own courtyard. Its reception area did not have a large area but was uncovered. Moreover, its shape and proportion resembled that of the Cruces 2 house since the casapuerta had the shape of a doorway, gave access to the stable (which had a mezzanine), and windows looked out onto it (

Figure 18).

4.1.2. Main Rooms (Salas)

The main rooms were of similar rank to the palacios (rooms), and were even of a higher order than they (its average surface was 15 m2). These were located on the ground floor around the courtyards and portals and on the upper floor in the corridors. The alarifes (master builders) described them in detail, so it is understood that they considered them to be important rooms within the hierarchy of spaces in the house. This importance is verified when calculating their surface area, which results in an average of 22.80 m2, larger than that of the palacio itself. They usually had another story above them or had gabled roofs. Their importance, not only constructive but also aesthetic, is further enhanced when it is known that they were decorated with tile almatrayas and white marble slabs at the entrances, and with tiles and alizares on the walls, which were usually also whitewashed and painted.

All the houses analyzed had at least one main room with a larger surface area than the median calculated for the rest of the city. In the Cruces 1 house, we found a room that had knot-worked doors (puertas de lazo) with shutters and a plaster arch. It was mortar plastered and had flooring of

ajembrilla (a mixture composed of lime, sand, and

arista, and produced a reddish colored surface finish on floors), perhaps because it was not in a good state of preservation at that time. This room had an area of 27.5 m

2 (ten and a half Castilian yards long by four Castilian yards less a quarter wide) and was gable-roofed on an eight-loop frame with

limas moamares and had a partition

arrocabe (limas moamares were double limes, one in each of the planes of the contiguous slopes, used in the curdled structure to delimit the dowels of the panels; arrocabe was an ornament in the form of a frieze at the top border of walls, made from plasterwork or wood, generally, it is organized as a decorative frieze) [

18] (pp. 623–658).

For its part, the main room of the Cruces 2 house with an area of 30.6 m

2 (twelve-and-a-quarter Castilian yards long by three-and-a-half Castilian yards wide) had a portal in front with an almatraya of tiles and tablets and an azonal of white marble slabs. In addition, the portal was decorated with an alfarje (a wooden ceiling) of a loop of two

sinos and a chilla and had a series of arches (danzas de arcos) on pillars of masonry along with its demuestras (columns on a wall, pilaster). From this portal, one entered the room, crossing though two doors with an arch of plasterwork of cuchillo. The room was paved on both sides with an almatraya of tablets, which began at the portal. It was roofed on a flat structure composed of beams, almojairas (a linear element in an alfarje or wooden ceiling smaller than beams), alfarjías, a half guarnición (ornament), and a zaquizamí (zaquizamí is a false ceiling of plaster or boards, sometimes decorated with plasterwork, laceries or with rods in the manner of stonework) [

18] (pp. 685–686). Curiously, it had a window to the portal with an iron grille.

In the case of the Cruces 3 house, the main room was preceded by knot-worked doors. It had an almatraya of tiles that continued into the room and reached the boundary wall. The room was paved with bricks and the entrance had the continuation of the almatraya of the portal. It had an area of 33.4 m

2 (twelve Castilian yards long by four wide) and was gable-roofed on a framework of

par y nudillo with three pairs of triangular trusses (tijeras), decorated with plasterwork arrocabe (

Figure 19).

Finally, the room where the deer almatraya was located in Guzmán el Bueno had dimensions well above average, like that of a palace. With a floor plan of 67 m2 (originally), it is the largest of those studied. Its great size added to the richness of the finishes in floors, walls, and ceilings must have been overwhelming, considering the human scale; one must have seemed disproportionately small upon entering this room. We assume that this was the intention: to overwhelm, to surprise, to make the visitor feel the weight of the power of the family that lived there.

The ceilings were composed of painted beams, with arrocabes, chillas (thin board, whose width varies between 12 and 14 cm and two and a half meters long), and menados (geometric decoration in the alfarjes; complementary planks that cover the streets of the framework), the walls were decorated with white, green, and black small tiles in geometric motifs (alizares: small glazed tiles or azulejos), and the floor was olambrado and decorated with the immense almatraya as a reception carpet that extended to the outer edge of the portal, as mentioned before.

4.1.3. Women’s Quarters (Servicios de Mujeres)

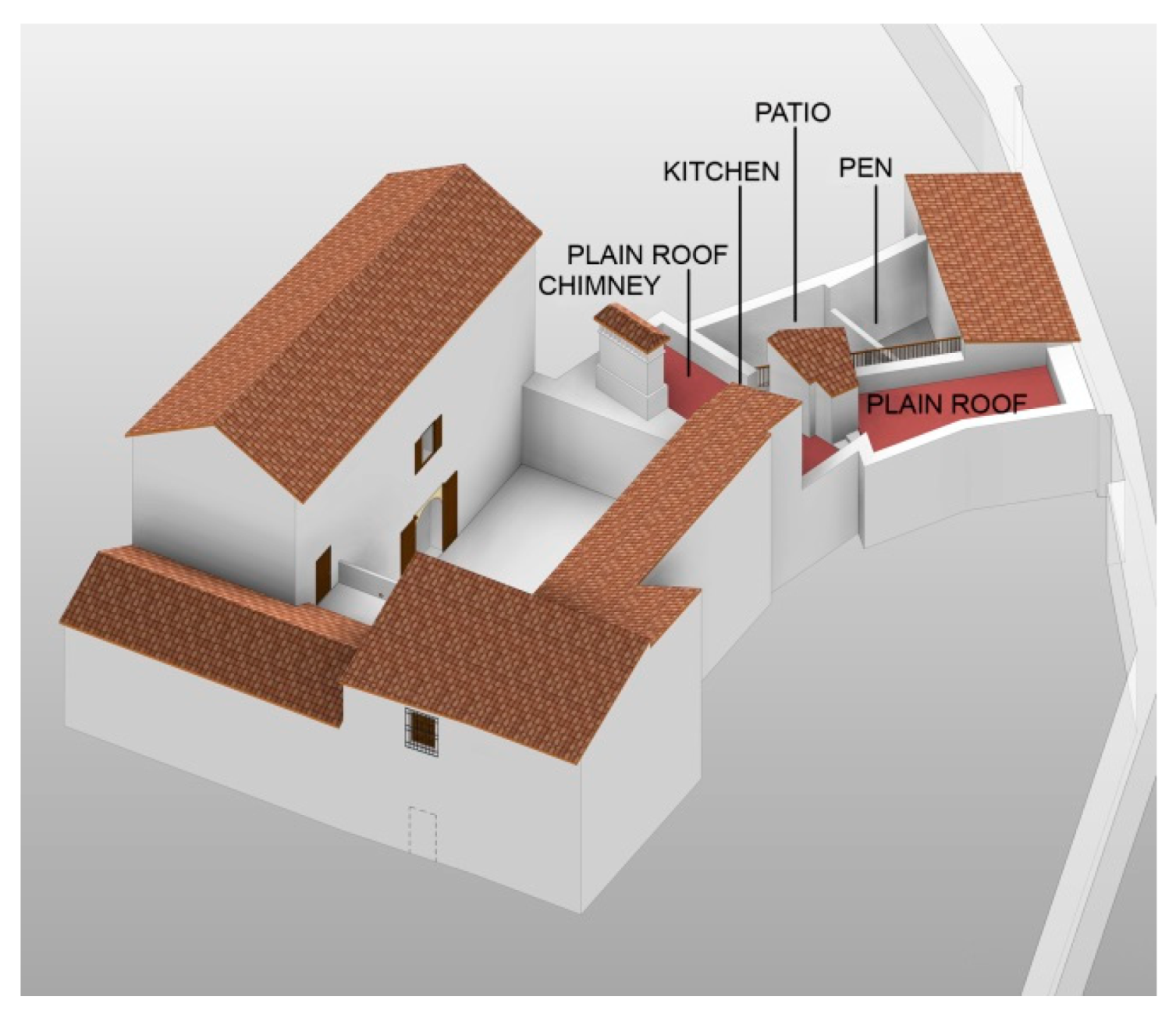

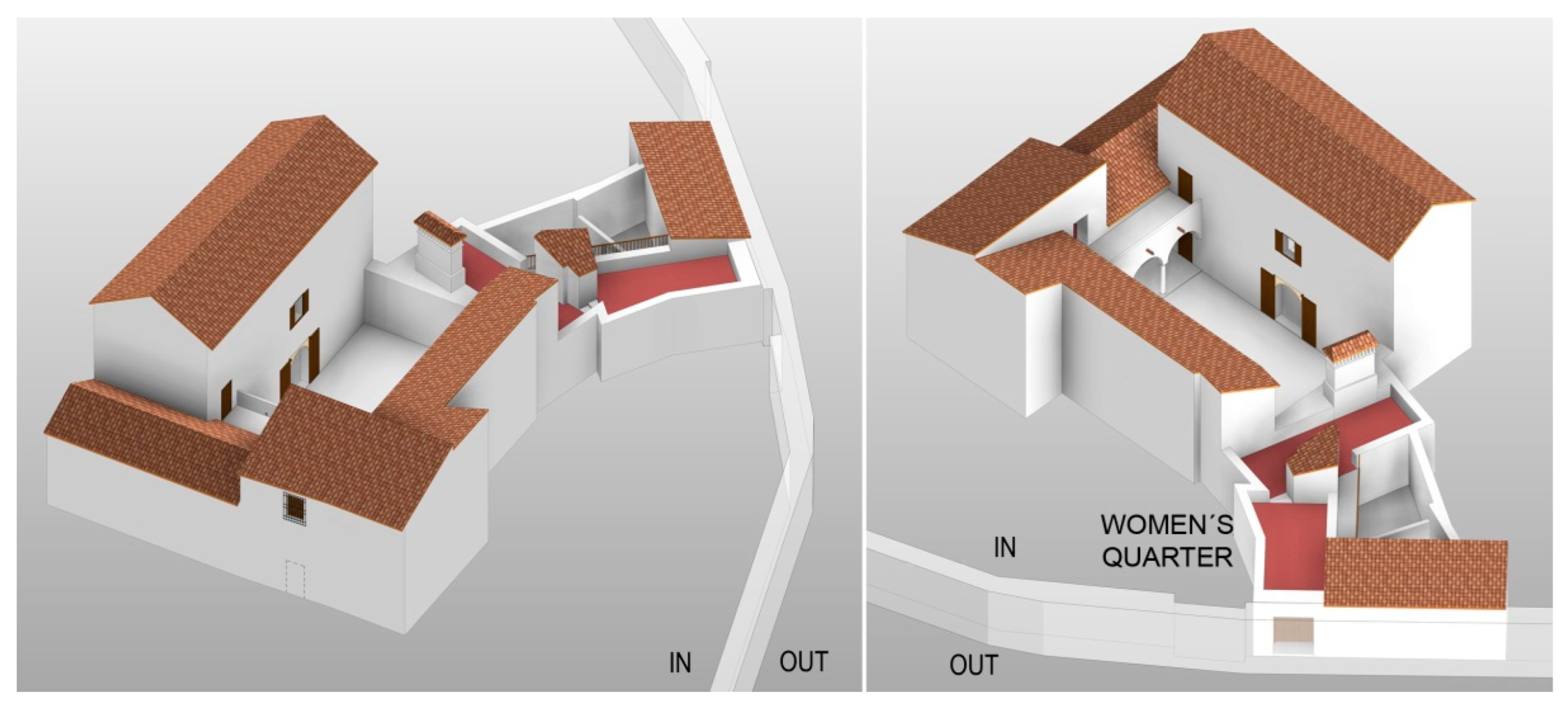

Another characteristic space of large houses was the women’s quarters (servicio de mujeres), also called “patio of the servicio de mujeres” or “cuerpo de mujeres”. They were a set of spaces in the most intimate part of the house, composed of a patio with a well, a kitchen with a hearth, a room (on the ground or the upper floor), a plain roof (for drying out clothes), and a cattle pen (corral) with its latrine [

38]. The houses that had this type of quarter had an average occupied area much larger than the rest of the city (about 400 m

2). Therefore, their owners or tenants must have been in a high place in the Sevillian social hierarchy (service, women’s service, in most cases refers to the women’s yard as well as the women’s section. They were a set of spaces destined to the work of the women inside the house. It used to be located at the back of the house). For example, the Casa de Contratación of Seville, adjacent to the Real Alcázar, the Casa de Pilatos [

39], and the Palace of Dueñas had this type of space. Women’s quarters were in many other houses in Seville, including those owned by the Cathedral and in the hands of Converso families.

Women’s quarters did not have a fixed location in the layout of the house, and, although their installation in the deepest area and away from the street could be justified, given the tasks that were attributed to them, this was not always the case. Rather, they were adapted to the shape of the plot, and were conditioned by its size and also by the history of the ownership, its groupings, and segregations.

In conclusion, the women’s quarters, and their associated spaces in the Sevillian houses of the 16th Century, were a set of uncovered places (mainly courtyards, plain roofs, and pens), around which other covered areas were arranged (kitchens, pantries, chambers, and other rooms that we will see in more detail later). These rooms are defined by their function and are not always clearly separated from the rest of the house, as the casuistry is wide.

Among those studied, the Cruces 1 had this type of space, consisting of a kitchen, a patio, a pen, and a plain roof. The Cruces 2 house also had a set of spaces that could be the equivalent of the women’s quarter. The alarife who wrote the survey did not mention the specific term, maybe because it did not have a patio. The space consisted of an entrance with a staircase, two alleys (one with the latrine), and the kitchen (with a well, sink, basin, and chimney). It also had upper levels as rooms for women and a plain roof.

As has been seen in many of the Sevillian houses, there were constructive and decorative elements that denoted investment in architecture and purchasing power. They are not lavish, but there are frequently richly-forged ceilings, plasterwork in arches, tiled walls and paintings, the use of marble, or ornamental woodwork. However, the absence of these refinements in women’s quarters would confirm the functional conception that builders and users had for these spaces. That is why, from the point of view of the study of emotions, these types of spaces should not only be studied for what they signify within the house to which they belong, but also for what was lived and experienced in them on a daily basis: joy, loneliness, sadness, melancholy, fear, nostalgia, etc. -so characteristic of the spaces lived in by women, servants, and children, among others (

Figure 20).

In the analysis of women’s quarters, it is revealing that these spaces were used by women, wives, or Converso mothers, to educate their children in Judaism or better said, in crypto-Judaism [

40]. Those women who had not accepted baptism willingly became authentic transmitters of the principles of the Jewish religion. It is significant that Caro Baroja found, at the beginning of the 17th Century, examples of the personality of those women whom he describes as priestesses. And he explains it, because although “Judaism is a masculine religion in which the man always plays a leading role and the woman is excluded from participation in the synagogue, crypto-Judaism developed thanks to them.” [

5] (vol. 3, pp. 139–140).

But it is necessary to go further back in time to verify what Caro Baroja distinguishes as “the religious personality and strength of women” in the private family sphere. At the end of the 15th Century, when the first inquisitors arrived in Seville to persecute the Conversos, there is already evidence for this “female priesthood.” In the absence of a rabbi, women pursued the same goal: teaching children the Mosaic doctrine and perseverance in the ancient faith. A piece of information that surfaced in the inquisitorial process that followed the Sevillian family of the Benadeva at the end of the 15th Century is sufficient to illustrate this. According to Ollero, who studied the process in detail, the Sevillian converts of that time were aware of differentiation, and they assumed their ancestors, the economic functions they preferentially exercised, the norms of their religious life, and the adoption of their own behavior and mentality [

41].

Converted women were not excluded from this characterization except that they did not participate in the business of their husbands. In that tragic historical context for the Converso community of Seville, one of them, Isabel Suarez (wife of Pedro Fernandez Benadeva) stood out. Ollero defines her as a strong woman, who kept alive the flame of the Mosaic faith among her children. One of them, Francisco, gave her away in exchange for his life while interrogated by the inquisitors. He was quite explicit: “the father did not intervene in her religious formation” and never expressed his religious ideas. On the contrary, his mother began to indoctrinate him in the practice of the fundamental rites and ceremonies of Judaism when he reached the age of eleven [

41] (p. 71). It was in this way, within the walls of the family home, that Isabel taught her children. But the confession of Francisco Suarez was decisive for the persecution of his mother who managed to escape from the inquisitors by fleeing to Portugal (the full confession can be found in the appendix) [

41] (pp. 97–98).

It is well known that the educational role of this woman (and others like her) had to be developed in the space of the house reserved for women, a hidden place, where men or neighbors from outside the house could not enter. And that space could not be other than the women’s quarters, a suitable place for the religious purpose that was pursued, such that an area outside the ordinary religious environment and designed for work, rest, or female conversation was radically transformed. And although it is true that this space already existed prior to religious persecution, since it was but the result of a Mediterranean cultural conception of women and their place within the house, it is no less true that its educational-religious function, replacing the rabbinical school and perhaps the synagogue itself, gave it an importance and a distinction that transcended its daily functions and, at the same time, characterized and distinguished the Converso houses from the others.

4.2. Materialization of a Sevillian Singularity

An example of how the fear of one of the families was able to change the distribution of their house because they wanted to appear more Christian than Jewish has been brought up. For example, other families installed decorations at the entrance or main rooms of their houses to externalize their desire for acceptance, social integration, and religious inclusion.

Nevertheless, fear was often hidden behind a curtain of ambition and ostentation, not only of economic power but also of religious power [

42,

43]. Houses contained in the old Jewish quarter emanated these emotions and pretensions. Those materialized in very elaborate and highly representative ornamental details in their rich and spacious rooms. The main rooms, the patios, the religious images on the facades of the houses, the decorative motifs, the finishes, or the carpentry could give us clues about the forms of the aesthetic and spiritual expression of its inhabitants. Moreover, if there were signs of ostentation, then astonishment and envy for the outside observer were intended and generated.

Studying the religious origin of the tenants, it is verified that there are descendants of Converso families. Therefore, they make us think about the materiality of fear through the inclusion of religious images in places of the house that are most visible or frequented by guests (façades, casapuertas, patios, portals, main rooms).

Some of the decorations that can be identified with religiosity or spirituality are the decorative motifs on some floors, based on stags (given that popular iconography depicts Saint Giles and other saints accompanied by a hind, it is not surprising that his image was used to decorate the floors of the houses of pious and wealthy families). Also bases on deers (the deer appears in Pliny’s Natural History and other classical writings as an animal that is the enemy of snakes, which is why it was quickly adopted by Christianity as a representative figure of Christ who defeats the serpent of hell; representing the victory of the Church over the Devil. As a result, there are numerous medieval depictions of the stag and allusions to it by St. Augustine, St. Eustace, St. Bernard and others. The stag also symbolises the human soul and appears in one of the books of the Old Testament. The drinking deer became a new iconographic motif associated with baptism, a sacrament in which water quenches the thirst of the spirit and cleanses original sin; thus deer figures are frequently seen on baptismal fonts and also on chalices. In the case of the Jewish-converts, this refers to a self-affirmation of the act of baptism to the outside world to the visitor who would be responsible for reporting it socially, as further proof of a sincere Christianity). These were used as the main motif in almatrayas, azonales, or olambrillas (an almatraya was a rectangle on the pavement made from tiles or stone; an azonal was a decorative tape, border o frame, on the pavement that forms the boundaries of a carpet of tiles or marks the edges of a room; and an olambrilla is a decorative tile of about seven centimeters of side, which is combined with rectangular tiles or bricks, to form pavements and to cover baseboards) [

18] (p. 625–626).

In our specific context, archaeological evidence of the presence of deer in a large almatraya has been found in the portal and at the entrance to the main room of the house of Guzmán el Bueno [

44] (

Figure 21). The image of the deer, with horns and in different positions, is striking for its spiritual ambiguity, both Christian and Jewish. For this reason, the owner of the house who commissioned the almatraya wanted, on the one hand, to capture the attention of the visitor, generating astonishment and envy, and on the other hand, to show a spiritual background that linked the house to its inhabitants. This almatraya not only is highlighted for the image of the deer, but also for its size (450 × 325 cm), design (cuerda seca –dry cord-, a Gothic figurative decoration and Mudejar tradition from Granada and Seville), and the origin of its ceramics, both local and from Manises (Valencia, Spain) [

45] (vol. II, pp. 466–468). (

Figure 21).

It is also known that there were images painted on some facades showing the Virgin Mary (Our Lady) under various titles (the Fifth Anguish and La Magdalena) and saints, such as Saint John, closely linked to the life of the Messiah. These were placed at the entrances or near them, in a door house or hall, in a portal, or on the very façade of the houses. (The following references to cervatallas have been found among the written descriptive records of the Cathedral: In Abades Street, in a casapuerta [

30] (section II, book 9163, sheet 205v) -they were owned for life by Melchor Moreno, a fish market broker from a Jewish-converted family-; another in Abades Street, in a mezzanine [

30] (section II, book 9163, sheet 207v) -they were owned by canon Luis Peñalosa “closed with a cervatalla of their skipped tiles”-; in Mármoles Street, in a room, [

30] (section II, book 9163, sheet 299r) -lived by the juror Alonso Ruys, from a Judeo-Converse family “at the entrance it has an almatraia with two white paving stones and the azonares (borders) of modarça tiles the floor is of holambrado and the setting of zarvasallas of glazed tiles”-; in Santa Cruz, in the almatraya of the dining room, [

30] (section II, book 9163, sheet 344r) -Francisco Ruiz clergyman chaplain of the royal chapel of Nuestra Señora de los Reyes had them for life-; in San Salvador, at Las Siete Revueltas Street, in a patio, [

30] (book 9717, sheet 369r -Juan Hurtado, scribe of Las Gradas from a Converso family, had them “is a holambrado pavement tile floor with a cervata garnished with glazed tiles”-).

4.3. Alteration of a House Entrance: Cruces 1

At a historical moment in which the city had not yet forgotten the pogrom of 1391 or the drama of the expulsion and the end of the Jewish quarter as a unique neighborhood (separated from the surrounding areas by an interior wall), reforms were carried out in the house by Téllez, probably before being sold to the Cathedral chapter. It could be considered a paradigm of the transformation that took place in many of the houses that belonged to the Sevillian converts.

In this sense, the Téllez family, who lived in a house on Madre de Dios Street and whose pen was enclosed by the wall of the Jewish quarter of Seville, decided to change the layout of their house. Once the Jewish wall was demolished, the main door was opened to Borceguineria Street, as it was considered one of the most active streets and, most importantly, because it was outside the Jewish quarter.

It is not known exactly when this redistribution took place, but we know that since 1502 the property had belonged to Cathedral chapter, which in turn leased it to the family that had owned it until then, that is, the Téllez family. There are several reasons why we have come to the conclusion that their house was altered so that its inhabitants did not enter through the original door that led to the Jewish quarter, but through the opposite end, at the back of the plot, through which was the way out of the quarter.

Considering the richness of the spaces at the back of the house, such as the portal or the main room (“Also from this said patio we enter a portal […] and this wood is supported on three round arches alfiçarados and two marbles with bases and capitals […]. From this said portal we enter a room that has a few loop doors with their shutters and it is mortar paved and ajembrilla and it is ten and a half varas long and four varas wide minus a quarter and the top is gabled roof on a loop armor of eight with its litures [limes] mamares with its arrocabe of tiles I say of partition and the arch of the door is of jesería”) [

30] (section II, book 9163, year 1542, sheet 341r). And taking into account that the women’s quarter (consisting of a patio with well and basin, a kitchen with fireplace, a pen with latrine, and a bedroom) used to be at the back of houses, suggest that the house was transformed at some point before 1502, and the door (casapuerta) was opened towards Cruces Street (now Mateos Gago). In other words, the original order of the house was reversed.

Also, even more peculiar is the fact that the highest elevations of the house are oriented towards Madre de Dios and not towards Cruces Street (“Also we went up a staircase […] a window to the street that goes to the monastery of Madre de Dios with an iron grille […]”) [

30] (section II, book 9163, year 1542, sheet 341r). The first corridor facing that street is two stories high and has a window in each upper room (soberado). The survey of 1502 confirms this, saying it had a shutter towards Madre de Dios (“And then ahead there is a portal (11) roofed with a Moorish style roof carved on three arches with two marbles in which there is a palace (12) roofed with a Moorish style gabled roof with an alhania on the right hand in the portal on the left hand there is a cellar with a pantry (13 and 14) […] which has a shutter that goes out to the mother of God to the street”) [

30] (section II, book 9163, year 1542, sheet 341r). (

Figure 22).

The mentioned cellar would correspond with the previous casapuerta. It is curious that the survey of 1542 for the same house does not mention the shutter, but it does mention an ancón (a covered space, open on one of its sides, similar to a cubicle) of a Castilian yard wide (in Seville 835 mm), which we suppose would coincide with the opening of the closed shutter.