Abstract

This article examines the application of conditions of authenticity within the context of built heritage management in areas of political conflict, where heritage management can be seen as a political act rather than a means of protection. It focuses on values attributed to built heritage that can be targeted or reinvented by the dominant power in areas of conflict with minorities being powerless to intervene. The argument is built around the Agios Synesios Church in North Cyprus, which continued to be used by the Greek Cypriot minority following the island division in 1974. Although their way of life has been compromised, they have embraced forced change through using the church to maintain their ritual and religious practices; by doing so, they negotiate their values towards their heritage. In this case, the study shows that the conditions of authenticity are difficult to meet, given the means through which heritage management can be manipulated. Accordingly, the article aims to contribute to general discussions on the vagueness and enigmatic conditions of authenticity in areas of conflict. Different buildings in areas of conflict around the world suffer because of the political nature of heritage management, which makes the criteria of authenticity unviable.

1. Introduction

Changes in cultural practices, values, and social norms throughout time are inevitable. These transformations mostly occur progressively in different generations. However, conflicts may accelerate and force new changes in cultural and social practices, especially when power dynamics may influence the different parties involved in a conflict. This is evident when minorities are involved, who need to develop ways to both protect and represent their identity among the culture of the majority [1,2]. As such, buildings belonging to minorities, who are forced into new circumstances, might gain more significance and become more symbolic [2]. In other words, buildings become representations of the collective memory of the impaired minorities, especially those associated with their culture, as a result of changes in the political conditions [3]. This poses the issue of selectiveness in heritage management.

Heritage management in areas of conflict can become highly politicized. Values associated with built heritage at a given time and place are formed by the contexts and actors involved and are changeable. The changing values and approaches to heritage management can shade authenticity, a foundational concept in heritage conservation.

The conditions for authenticity have been provided by the Nara Document [4] and have been revised under Nara +20 [5]. Although the revised document respects social changes in different cultures as conditions of authenticity, this does not include conflicts of a political nature. When changes to a place may have been deliberately forced and the spirit of the place’s “context” has been compromised, then coming to terms with authenticity in areas of conflict becomes critical. One of the questions that emerges is “which values remain and for whom?”.

The objective here is to investigate value change as a condition for authenticity through the case of religious heritage in areas of conflict and to relate it to heritage management that is open to various interpretations. The article argues that the pre and the revised Nara Documents and the Operational Guidelines of UNESCO [6] on the conditions of authenticity are difficult to meet within the heritage management in politically unstable contexts. Furthermore, the criteria provided by these charters/conventions falls short in addressing the role of the community within the discourse of heritage management.

This is argued in relation to the case study of the Agios Synesios Church located in the village of Rizokarpaso in North Cyprus. Rizokarpaso represents a rare example of mixed ethnic groups in Cyprus (Turks and Greeks) living together today. The Greek Cypriots, who were the vast majority of the residents in the village prior to 1974, were not all displaced to the southern part of the island and have continued to live in their own houses and use the church. The church is the most prominent among the many churches in the village, and it is still intact. Although the building is true to its use, function, aesthetics, and physical appearance, changes in the context and in the practices of social and religious rituals have been reconfigured, an act which demonstrates the Turkish presence following the conflict.

This paper questions whether such buildings, which are still intact and are truthful to their original use but exist in areas of conflict, can still clearly represent the conditions of authenticity. Answers to these questions will help to critically appraise diverse approaches to heritage studies across the world through broadening notions of authenticity that are linked to built heritage.

This qualitative research, based on a theoretical discussion about authenticity in areas of conflict and a case study, includes the following:

- An extensive literature review on the issue of authenticity in heritage management and political conflicts and wars.

- An examination of the publicly available documents about the church from the Department of Antiquity in North Cyprus and inventory sheets done after 1974. Apart from the documents, the description of the church available in Rupert Gunnis’s book Historic Cyprus: A Guide to Its Towns and Villages, Monasteries and Castles helped to depict changes to the building by comparing it with the existing condition of the church. This source book is important since the literature about the history of Cyprus’ churches mainly focuses on the monasteries and predominant churches with architectural significance. With the exception of Robert Gunnis’s book, the information about the churches in rural areas is quite limited and dispersed. Published in 1936, the book includes Gunnis’s observations derived from site visits during his employment in the Cyprus Museum between 1932 and 1935 as an inspector of antiquities.

- An in-depth observation of the village, the church, and the surrounding area, as well as interviews with both Greeks and Turks, including the priest and the muhtar (elected community member in Turkish).

The article is structured under five headings. The introduction provides the background information about the study, and the second chapter offers an extensive literature review on the concept of authenticity in built heritage and conflicts. The case study is presented in detail in the third section and provides a basis for the discussion in the section that follows. Finally, the fifth section concludes that the conditions of authenticity for built heritage in areas of conflict should be revisited and the mechanisms and guidelines reviewed.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Attributes of Values and Authenticity in Built Heritage

Authenticity has been an ongoing subject of debate in the field of heritage studies. In the case of built heritage, the importance of maintaining authenticity was stated in the Venice Charter in 1964 [7]. This was considered to be one of the pioneering steps in establishing built heritage conservation as a professional and scientific field, thus giving rise to the importance and acceleration of professional activity in both theory and practice [8,9,10,11]. In the preamble of the charter, it is stated that our common responsibility is to safeguard our heritage for future generations, and “our duty is to hand them on in the full richness of their authenticity” [7] (p. 1). Such a statement raises the question of what authenticity is and how it can be met.

Cultural heritage and its conservation became a worldwide concern and required the help of both national and global heritage organizations. This resulted in the adoption of the “Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage” by the General Conference of UNESCO in 1972, which came into force in 1975. To be listed as a World Heritage property, a cultural heritage asset should have an “outstanding universal value” and pass the “test of authenticity” [12].

The requirements for World Heritage properties in the convention rekindled the discussions about authenticity. Focusing mainly on this, the meeting held in Nara, Japan, in 1994 addressed the respect for cultural diversity when judging the value and authenticity of cultural heritage. The Nara Document on Authenticity, as an outcome of the conference, states in its 13th article that authenticity judgements are based on different information sources that may have changed according to the nature of the cultural heritage, its cultural context, and its evolution through time [4]. Although there are no clear guidelines for the examination of cultural context in heritage studies, this requirement exists in the international documents. These sources comprise “form and design, materials and substance, use and function, traditions and techniques, location and setting, spirit and feeling, and other internal and external factors” [4]. The Nara Document defines authenticity in terms of both tangible and intangible aspects of heritage assets and underlines that these are open to interpretation by different cultures and even within the same culture. The Nara Document experts met again in Japan in 2014 and released the supplementary text of Nara +20, which built upon the Himeji Recommendations, examining alternative approaches to better understand cultural diversity and heritage [5]. It states that values associated with heritage are more socially based rather than technically or scientifically based and calls for an assessment of the credibility of sources further determining authenticity. The text of Nara +20 suggests that the determination of authenticity should be based on periodic reviews that accommodate changes over time in perceptions and attitudes, rather than on a single assessment based on a “meaningful expression of an evolving cultural tradition” and the “resonance of group identity” [5].

A more simplified understanding of authenticity states that it is essential to understand the distinction between the “facts” and “values” of built heritage. Facts are objectively verifiable and inherent to the property without the need of an external observer, and values are attributed to the property by people and therefore may change depending on time and the person performing the evaluation [13] (p. 5).

Accordingly, it can be stated that changes in values, beliefs, and practices can continuously be renegotiated. Nevertheless, what the above does not clearly address is the fact that changes can be the result of a forced cause or an exercise of power, which may have initially led to the changes in a building.

Theories have emphasised the different nature of places that should result in different intervention and solutions, such as notions of place and sense of place of genius loci [14]. Buildings are much more than a mere location and not just an outcome of a mathematical calculation. “Places” as such achieve their symbolic meaning and signification from social meaning, depending on the richness of the social and cultural experience [15]. According to this approach, it can be said that the authenticity of a historically valuable building is totally lost if it is exhibited in a museum and away from its locus. The context and the culture in which a building is situated comprises different tangible and intangible elements and images that provide social values, meaning, and aesthetic values: an ontological status. Together, they allow architectural works to appear for experience and to establish an ontological relation with the environment that is authentic.

The issue of context and spirit of place is addressed by several recommendations and charters concerned with contemporary interventions within significant historical settings and heritage. This concern was raised due to rapid urban developments that continue to dominate the world. Hence, the UNESCO Recommendation Concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas [16] and the Washington Charter [17] were established to provide principles and guidelines, particularly around sites inscribed on the World Heritage List, against potential threats (see [18]). Critical cases were discussed on individual bases, considering assessments related to visual impact, skylines, views, and integration with the changing context. Furthermore, the revised Burra Charter, The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance, was adopted in 2013 to advocate for cautious changes in regard to the wider settings of a place with cultural significance [19]. The Burra Charter’s emphasis is placed upon an understanding of the context of a place as an immediate and extended environment that contributes to its significance and character. According to the charter, a place includes the visual and sensory setting and the retention of cultural and spiritual relationships that contribute to its cultural significance, as well as the meaning associated with signifying and representing groups of people. Thus, the issue of change to a place discussed at length in the preamble states that it “should not distort the physical or other evidence it provides, nor be based on conjecture” [19] (p. 5). However, the application, explanation, and methodologies related to the contextualization of contemporary architecture in historical settings are not mentioned in the UNESCO Recommendation Concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas [20] nor is the amount of change that would be accepted in order to maintain a place given in the Burra Charter.

The suggestions by the charters to include the wider context of built heritage has been criticised for demanding a predefinition of the characteristics and qualities of the place before they are thoroughly examined in a robust manner. The contexts differ according to each culture and within the same culture, as noted by the Nara Document [5], but should be “experienced within the cultural framework of those who have created and sustained it” [21] (p. 46). Having standards that address the issue of relating old to new in an entirely tangible manner does not address other intangible qualities associated with the social, economic, cultural, and even political, as in the case of this study.

The concept of authenticity and heritage has also been explored in the tourism sector, especially after MacCannell’s studies [22] on tourists’ desire for an authentic experience and Goffman’s [23] studies on tourism sociology (see [24,25]). The further call for studies on the vagueness of authenticity as debated by researchers in tourism [26] forged a link between tourism and authenticity, and this came to the fore in tourism literature. Increasing globalization and the resulting interest in different cultures, which can be experienced through authentic cultural expressions and assets, also helped the growth of literature on the subject [22,27,28]. Such an increase has also been welcomed by heritage professionals and national and/or local administrators who are dealing with heritage management and who, in some cases, see authenticity as a critical aspect for heritage sites marketing [29]. From a tourism perspective, the authenticity of heritage assets—especially monuments in this case study—is considered as a motivator for tourists on a global scale. Yet, the discussion revolving around the case study of this research focuses on authenticity for minority groups in areas of conflict, where heritage management goes far beyond purely tourist concerns.

2.2. Authenticity, Heritage, and Conflicts

The issue of dealing with built heritage in times of armed conflict has attracted much attention from scholars, specifically with cases that surfaced in the aftermath of destruction in relation to authenticity. Thus, the international charter’s recommendations related to cultural heritage affected by conflicts are vague and do not propose clear ways to deal with such situations or assist in “future practice” [30] (p. 33). The Venice Charter focuses on cases on an individual basis rather than offering detailed criteria and principles to deal with such situations [7]. In the recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, including the glossary of definitions in 2011, very little is said about conflicts: “Changes to historic urban areas can also result from sudden disasters and armed conflicts. The historic urban landscape approach may assist in managing and mitigating such impacts” [31]. Similarly, the Recommendation Concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas suggests that acts to rebuild deliberately destructed cultural properties in the aftermath of conflicts can be “justifiable only in exceptional circumstances” [16].

Extensive efforts continue to be directed toward healing communities and their heritage in the aftermath of wars, given their lack of resources, such as money and expertise. This complicates the issue of heritage management undertaken by governments, stakeholders, and civic societies regarding their decisions, which have not always been beneficial. Roha Khalaf, for instance, questions, “If a World Heritage property is destroyed and later reconstructed, could it still be recognized as World Heritage?” and argues that this issue “remains open to debate”, given the political nature of the systems and their interests with decisions related to the reconstruction of destroyed cultural heritage [32] (p. 262).

Scholars argue about the issue of reconstruction following conflicts as a dynamic process, including meanings, practice, and management. Khalaf [32] sees reconstruction based on the Nara Document as an act of restoration rather than “the artistic or historic evidence” only [4] (p. 265) or the “specific mode of conservation” that relies on similarities of heritages around the world [33] (p. 309) and less based on power effects [34] (p. 13). Likewise, Mattias Legnér invites us to look at heritage reconstruction under the notion of a process rather than simply the management and conservation of resources. Inviting an active “construction and negotiation of meaning through remembering”, and identity formation in the sway of safeguarding heritage assets allows for a dialogue with the past and prevents the issue from becoming a static discourse [35] (p. 3).

Evidence shows that injustices and inequalities are sustained in some societies through the different measures of heritage management, especially around minorities and certain ethnicities. Management, according to Laurajane Smith, is a “Western Authorised Heritage Discourse” [36] (p. 95), which can be selective in the inclusion and exclusion of places, practices, and buildings, and this can have an undermining effect. Another aspect is the initiation of the procedure for heritage recognition according to the World Heritage Convention, which can only happen through recognized States Parties in their sovereign territories [33], thus leaving the control of heritage related issues to one side. Accordingly, the revised conditions of authenticity [5] attempt to address the imbalance in the representative list by the inclusion of new themes of culture and landscape in a less materialist sense and a “move away from a purely architectural view of the cultural heritage of humanity towards one which was much more anthropological, multi-functional and universal” [4]. Yet, it still shows that there are no changes to the values given to the States Parties in the selection list (see [37]). This is crucial in zones of conflicts, where one’s society overlaps with the “other dominant”, given that their cultural heritage is bound up with the “national” cultural narrative. Accordingly, the management of one’s heritage can silence some and expose others in the process by default [38] (p. 220).

Conflicts are different and complex in their nature and reveal different consequences to built heritage and its management. Spennemann argues that the preservation or non-preservation of built heritage expresses the values and the political will held by decision makers according to their contemporary values, which in many cases cannot be congruent with the expectations of the communities [39] (p. 8). In extreme cases, where the minority is marginalized by the majority, this act may lead into further marginalization and undermine cultural expression [39]. While much of the available literature is set in sites of determined conflicts [3,33], documented cases of ongoing conflicts are less exposed, especially when a dominating and suppressing power still prevails [33,40]. In the case of suppressed minorities during ongoing conflicts, identities are temporary established, and they may change in time and become more vulnerable [1], thus their integration within local communities is not always possible, and their voices are not always heard [41,42].

The attitude towards the transformation and actualization of identity highlights issues related to coming to terms with the conditions of authenticity for built heritage in areas of conflict. While authenticity recognizes the continuous change of cultures over time, it does not consider that in areas of conflicts, culture, people, and traditions do not evolve normally but by force. Accordingly, the provided criteria together with the Operational Guidelines of the World Heritage Convention in 2019 [6] to meet the conditions of authenticity can be effective within peaceful contexts, but in areas of conflicts, where values are negotiated in the sway of selective heritage management, they are critical.

The above literature review concludes that buildings targeted in times of wars and conflicts cannot easily meet the conditions of authenticity, since changes in attributes do not progressively take place, leading to changes in the spirit and character of the built heritage.

3. Case Study

The case study of this research, which is the Agios Synesios Church, is located in Cyprus, the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Due to conflict between the Turkish and Greek Cypriots as inhabitants of the island, and following a war in 1974, the island was divided into two parts, north and south. Greek Cypriots living in the north were displaced to the south, while the Turkish Cypriots were displaced to the north. This paper refers to the religious built heritage of a small community of Greek Cypriots, who continue to live in the northern part of the island.

3.1. Churches in North Cyprus

Around 500 religious buildings affiliated with Christianity continue to exist in North Cyprus and are reminiscent of the Greek existence before the division of the island in 1974 [43] (p. 28). Several churches were constructed in different periods throughout history and followed the common style at that time, and they also differ in their origins as Orthodox or Catholic churches. After the displacement of the Greek Cypriots to the south, churches in the north underwent changes; many have changed uses, many have been converted to mosques, many have been left abandoned and eventually left to decay, especially if their location is not within close proximity to human settlements, and a few are still in use as churches. The reuse of churches has taken place since the Ottoman existence on the island in the year 1571. Major conversions of churches into mosques took place in the largest and most significant Orthodox churches in major cities; famously the Cathedral of Saint Nicholas was converted into Lala Mustafa Pasha Mosque in Famagusta, and the Cathedral of Saint Sophie was converted into Selimiye Mosque in Nicosia. Both are within the walled cities and are fine examples of Medieval architecture in the French Gothic style. The cathedrals came to influence many later churches and the style of the additions of existing churches on the island [44]. After the war in 1974, other examples of the reuse of churches as mosques or other secular uses took place in most villages in the north [45,46]. Following the displacement of the Greek Cypriots from their original villages, their homes, belongings, and heritage were left behind. Currently, very few Greek Cypriots continue to live in the north. Yet, the churches that are still in use are few and are mainly limited to: Apostolos Andreas Monastery in the Karpas peninsula and the villages around it, such as Sipahi, Rizokarpaso, and the Maronite church in the Kormakitis (Korucam) village on the northern coast. The Maronites are not of Greek origin but are Christian Arabs [47]. Some churches are still in use by foreign communities, such as the British, African students, and other minor communities in major cities.

In North Cyprus, conservation, safeguarding, and management is limited to some of the churches located in the main cities administered by the Cyprus Evkaf Foundation. The Evkaf, as a pious foundation since the Ottoman period, is internationally recognized as a legitimate authority over sites and monuments, including the Greek churches in North Cyprus [48]. The churches used as museums are administrated by the Directorate of Antiquities and Museums of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). Other funds, mainly from international Nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs), are invested in major and significant sites, while the smaller chapels and churches dispersed throughout the island are sidelined. The current political deadlock restricts both governments from safeguarding their heritage in opposite parts of the island.

3.2. Rizokarpaso Village and Its Churches

The village of Rizokarpaso (Dipkarpaz in Turkish) is located near the tip of the Karpas peninsula, to the east of the island, and is the largest village in the area (Figure 1). It is situated on the major and only route to the peninsula and is a stopping off point for visitors of the Apostolos Andreas Monastery.

Figure 1.

Location of Rizokarpaso on map of Cyprus (source: authors).

Before 1974, the vast majority of the population was comprised of Greek Cypriots [49]. Afterwards, some Turks migrated while some Greek Cypriots decided to stay, which makes the village notable for its binational population. Those who decided to stay were given TRNC citizenship. Turks from mainland Turkey came to live in the abandoned houses, living together with the remaining Greek Cypriots.

The village consists of three areas: Ersin, Polat, and Sancar Pasha, all of which contain different ethnicities. Today, the beaches and tourist sites around the village attract visitors, which generate a good income for the Turks [50,51,52]. Greek Cypriot families after the year 2003 (the year that both Turkish and Greek Cypriots were able to cross the “green line” that divided the island for 30 years for the first time) have been supplemented with goods, such as gas cylinders, vegetables, meat, food, and other necessary commodities, by the Republic of Cyprus government, delivered each Wednesday and distributed by United Nations agents. There is a separate cemetery for Greek Cypriots in the village, and a Greek school for elementary and secondary education, where students pursue their high school education in the south. Students learn in Greek, and they also learn Turkish.

Some of the churches are located in the core of the village while others are further out. One of the most famous, due to its popularity with being close to the coast, are the ruins of the 12th century Agios Philon Church, an Orthodox church in a Romanesque style rather than the more common Byzantine styles seen in the area. There are also the remains of a stone cathedral, from which the remnants of the ancient harbour are visible. Other intact churches are the Agia Trias and the cemetery church. The Agia Trias is mainly a one aisled barrel-vaulted structure with a polygonal apse and belfry. Some of its original features, such as the original floor, have been replaced with ceramic tiles and metal window frames. The only church still in use is the Agios Synesios Church, which is administered by the priest attending in Apostolos Andreas. He keeps the key to the church and admission is permitted through him at certain times. It is located at the centre of the village and is referred to by Turks as “Merkez Kilise”, meaning the central church, due to its dominant location and size.

Within the scope of this study, the discussion is limited to the Agios Synesios Church for the following reasons:

- Religious buildings represent the collective memory and existence of an ethnic and/or religious group.

- The church was built for the same purpose that it is being used for today.

- The church serves the Greek Cypriot community that continues to live today in the village.

- The church is intact and maintains its original form and most of its architectural characteristics.

- The church is the largest and most dominant within its location; yet, it is surrounded by other prominent monuments representing alternative narratives.

3.3. Agios Synesios Church

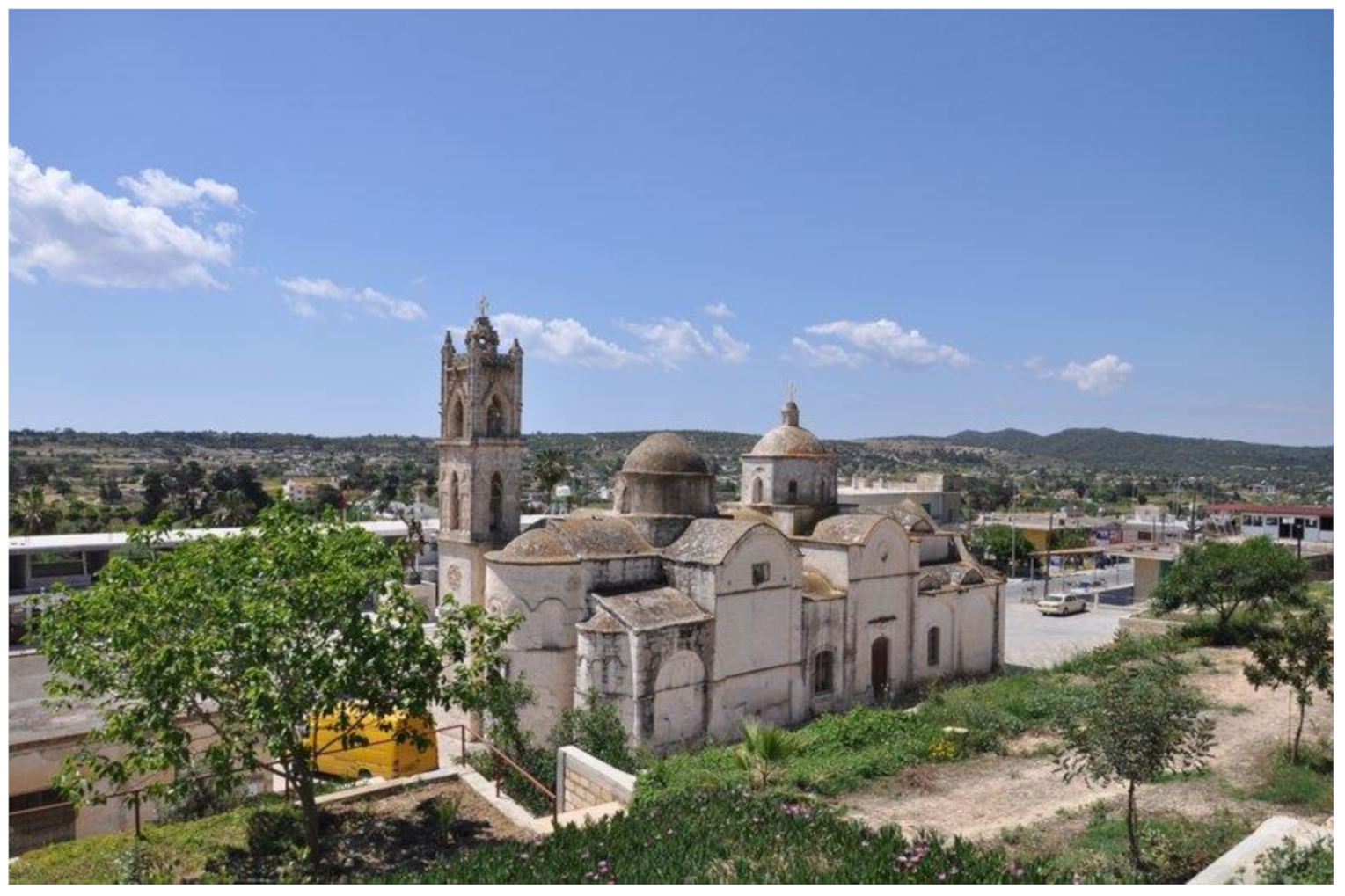

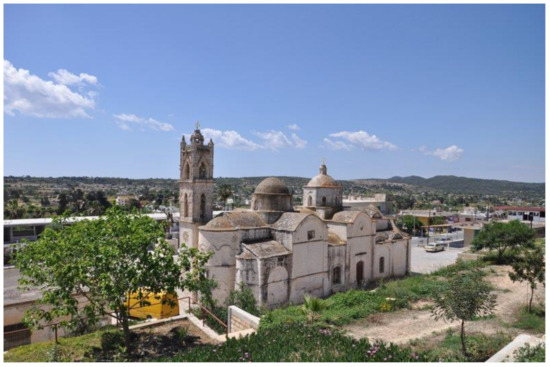

This principal Orthodox church is the largest in the village. It was dedicated to one of the early Bishops, Saint Synesios, during the Middle Ages [53]. He is believed to have been the protector of the Karpas Peninsula and responsible for the establishment of the Orthodox faith [54]. The cave in which he took refuge and lived an ascetic life is still in existence and is located across from the church. The church is prominently located within the village and raised on a platform approached with stairs that give it a monumental appearance. The plan takes the shape of an Orthodox cross with a dominant dome and cylindrical apse. The eastern part was built in the 12th century. The southern apse was destroyed while building the bell tower, but the two other apses maintain the Byzantine building style from the external arcading [53]. The dome was added later in the 19th century when it was extended. Another dominant feature is the belfry, which still houses the original bell. It is decorated with stone arches on the last two floors; however, according to Gunnis, it is a poor copy of Gothic details, derivative from the cathedrals of Nicosia and Famagusta [53] (p. 303) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Agios Synesios Church—rear view (source: authors).

The building has two entrances, the largest facing the street and the smaller one facing its yard. Both doors are made of timber. While the main one is not thought to be original, the secondary door features a pointed arch inspired in shape and decoration from the Gothic churches on the island. The dome and the bell tower are decorated with a stone cross at their centres. The internal floor is covered with mosaic, as is typical with churches on the island. Original frescos cover the isle of the church. Some mortar and plaster cracks can be seen on the interior walls of the building, and although they do not appear to threaten the structural integrity, humidity has spread to most of the interior walls (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Interior of the Agios Synesios Church (source: authors).

The different additions to the original structure, as observed, are common in many churches in Cyprus. They express the several layers of emerging needs in terms of function and meanings as a palimpsest of the successive users. They are evidence of the influence of the changing dynamics within Christianity and the many styles associated with it, bearing traces of the earlier and several ruling powers over Cyprus. While each period conveyed various and new advancements in building technology from their place of origin and around the world, all additions continue the same masonry building method and use. This gives significance to the various contributions from the different historic periods. Thus, the interpretation and emphasis of one period/aspect at the expense of the other is not appropriate here. This is because the cultural significance of the church—as a place to Christian worshipers—is much greater within the given dynamics of the conflict.

3.4. The Context around the Agios Synesios Church

Around the church, to the northeast and across the main road, there is the village commercial area, an arcaded structure containing restaurants, markets, and cafes on the ground floor with offices above, situated at the same level as the church. Two traditional coffee shops exist opposite each other, one primarily frequented by Greek Cypriots and the other by Turks (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Map of Rizokarpaso village.

Just behind the church to the northeast, a mosque has been built at close proximity and at a higher level. Its long minaret when approaching the village from the west appears to be a part of the church structure (Figure 5). To the west of the church and overlooking the yard, the Turkish coffee shop is located, and on the south are the statue of Turkish leader Mustafa Kemal Ataturk riding his horse and the Turkish flag (Figure 6). Although the church is of great significance to the village, it is no longer the prominent structure in the vista, now that there are other prominent structures competing in size and affecting the silhouette.

Figure 5.

The church with the mosque minaret appearing behind (source: authors).

Figure 6.

The statue of Ataturk located opposite the church’s main entrance (source: authors).

Major religious and social ceremonies take place in the church, such as Christmas, Easter, and Sunday masses, as well as funerals and baptisms, but only indoors. The church bell has been functioning only on Sundays since 2003 because the government forbade it. Also, different practices were not allowed to happen outside of the church, such as displaying the Christmas tree or other religious-related symbols.

Most of the changes which effected the use of the church happened immediately after the 1974 intervention that brought strong nationalist tendencies, especially for Turks. These changes included many Greeks leaving the village, Turks arriving from mainland Turkey to settle in the village, a building at the village square which started to be used as the coffee shop for Turks, the first sculpture of Ataturk (which was smaller than the present one enlarged in 2009), and the Turkish flag in front of the church. Greeks became unable to use the church yard, and the church bell stopped ringing. The mosque was built in 1983, which corresponds to the formation of the TRNC and the rise of nationalism.

Moreover, the priest referred to their inability to maintain the church due to the lack of funds and government restrictions, all of which has had an impact upon the life around the Agios Synesios Church. The key issues are summarised as follows:

- The church maintains its function and its users, who still practice the same culture. However, since 2003 the church bell has been allowed to function only on Sundays, and religious practices have not been allowed outside the building since then.

- The users can carry out superficial repairs and maintenance of the building itself, but not on its setting.

The ongoing regular use of the church in Rizokarpaso village by its users might appear at first sight to be an indication of peaceful integration. Nevertheless, after a thorough observation of life in the village, the issue of “them and us” is evident among the residents. After 4 decades of living together in the village, no real integration has taken place, and each ethnic group leads a separate life. According to the muhtar, better coexistence between both groups of residents existed before 2003, which included lending and borrowing money from each other, using the same coffee shop, and learning each other’s language. Today, after the provision of supplies by the Cyprus Republic government, this exchange has been lost.

Given the observations around the church and the village and the interviews with the locals, the question that arises is how can the changes around the church be managed given the condition of the conflict, especially when its ontological relationship with the environment has been reconfigured by force?

4. Discussion

Many scholars continue to question how to deal with built heritage and its authenticity, which may not be protected during conflicts. For example, Helen Walasek poses the question, “if attacks on culture during conflict are crimes against memory and identity, is there a duty not to forget?” and argues that it is hard for people to “to embrace forgetfulness” [55] (p. 294). Many cases of minorities around the world, including the Greek Cypriots in the Agios Synesios Church, embrace remembrance by continuing to use their churches for religious and spiritual practices to sustain their identity and existence in order to emphasise the ongoing cultural and religious connections and attachments to a place. This is common where political conflicts exist, and people continue to develop new concepts of identity for both themselves and their enemies [56]: “violence transforms the identity and agency of its authors” (p. 40). In addition, uncertainty invites new assumptions of identity for the political existence of people. These new assumptions affect people’s behaviour towards their enemies as well as their culture, including architecture [57,58,59]. In other words, their perception about heritage changes, and thus they change their strategies towards it and its management accordingly [40].

Consequently, this raises a further question: does the continuity of use within a changing context by the Greek Cypriots of the Agios Synesios Church allow for coming to terms with the conditions of authenticity? As stated in the beginning of this article, change is dependent on each generation that regenerates and reinterprets values form the past according to its own values [60]. Thus, in extreme cases like conflicts, change (forcibly) can lead to a false and loss of culture and traditional practices; therefore, it becomes essential to question how much change is tolerable to prolong the continuity of values through time in the discussion of authenticity. The given criteria provided by international doctrine and charters cannot really provide a mechanism nor a direct answer, and for many reasons, this is discussed throughout this section in relation to the Agios Synesios case.

Authenticity is a mandatory requirement and shapes international heritage practice. However, it lacks clarity in order to fulfil this obligation, and this problem remains in the pre and revised Nara Documents, which continue to prioritize materiality over intangible values attributed to heritage. The materialist approach to authenticity, which sees built heritage as objects (a value inherent in objects to be measured in a scientific manner), cannot explain the continuing power of authenticity and the experience of people that make some sites more “powerful loci” of authenticity [61]. This approach does not consider the wider social context and the influential role of people’s social lives and the way they perceive authenticity in a meaningful engagement [61]. In areas of conflict where change is a result of force, an essential question is where does authenticity reside?

Although this is asserted by the Nara documents in regard to the meaning and application of authenticity according to each culture and context, the documents do not clearly state that communities can negotiate where their authenticity can reside and which values can be attributed to being authentic. Many studies, drawn from cases of religious heritage, argue that a building, even one with many older elements obstructed through recent treatments, can still be understood as authentic due to the embodiment of spiritual beliefs and practices that are of great value to the community [62]. In such cases, spiritual values are prioritized over materiality, requiring heritage management to identify the clearest values expressed in a place [63]. This can be clearly seen in the case of the Agios Synesios, where the church gains more significance for the minority Greek Cypriots in the village, as it becomes the symbol of their continuous existence. Continuing to use and maintain the church and demanding the right to carry out other associated rituals becomes an aim in itself. The rituals and symbols usually overlooked become empowering tools to their collective memory and voice. For instance, the celebration of Saint Synesios in festivals each year on 26 March is an important event to the Greek Cypriots, where this church was dedicated to him. Although the “Cave of Saint Synesios” where he lived is not physically attached to the church and is across the street, it is the church that brings these people together for this and other celebrations. People pay respect and celebrate Saint Synesios in the church and not in the cave. Accordingly, what is important to people about the church is not the quality inherited in its materiality only but also the community’s claims and their perception of it, which makes it important in the first place.

One of the difficulties to come to terms with in relation to authenticity is the issue of subjectivity. Although UNESCO and the Nara Document on Authenticity of 1994, incorporated into the Operational Guidelines of the World Heritage Convention in 2019 [6], acknowledge and call for community involvement in identifying, managing, and determining the value of their heritage, including encouraging broader authenticity based on cultural context, the determination is still largely dependent on experts outside the communities associated with heritage, on State Parties, and on official governmental representatives [64]. Thus, decisions are made subjectively according to the way those in charge decide to perceive the situation. In this case, the appropriation of authenticity does not also allow for the shift “of hegemonic power from global to local” [64] (p. 595) and for capturing the individual dimension of authenticity, which is essential and connected to personal identity and self-realization [26]. States Parties, who are requested to ensure the involvement of communities and groups to identify their own values, remain the major identifier of the values of intangible heritage instead, due to the lack of mechanisms within the convention that can ensure the realization of such involvement [65]. Many scholarly discussions and cases continue to grow, arguing that values are held in the hands of the decision makers and their own political will, in some cases undermining and marginalizing many cultural expressions and communities [39,66]. In extreme cases, State Parties in areas of conflict may have subjective attitudes towards heritage management related to the “other” (see [33]). They can use ambiguity as a means to institutionalize the value system based on the knowledge of technical and aesthetic experts, which can undervalue minorities and manipulate them through ignoring their social life and the intangible values important to the authenticity of a place. The dominant force of State Parties ensures that minorities are eliminated in its decision towards the management of heritage through slow neglect and a drip feed of funding for maintenance, as in the case of the Agios Synesios Church. In regard to heritage management in North Cyprus, the Cyprus Evkaf Foundation is responsible for all Greek churches in the north, including the Agios Synesios Church. However, it does not assist further by controlling future additions and changes to the physical context but is responsible for altering the spirit of the place, such as the erection of new mosques adjacent to existing churches. These also exist in the villages of Beyarmudu, Mormenekse, Vadili, and Turkmen and many others in North Cyprus. Ince and Yuceer argue that many mosques were built in villages where existing churches had been used as mosques since 1974 [67]. Such new mosque construction is justified with the pressure imposed by the Turkish Cypriot community in these villages, who mentioned that “the reason for asking a mosque to be built was because the mosque was going to make our village look more Turkish and we, as refugees, would feel more rooted” [68] (p. 183). This is because of the imposed anxiety on the people following Greek Cypriot visits to their former villages and their churches in 2003. What is critical here is not only the change in the spirit of the place and the views but the exposure of existing churches to becoming abandoned and therefore allowing for slow deterioration, which will diminish them when not in use (see [69]). Therefore, built heritage will not retain its physical historical evidence, leading to further problems in heritage management.

Some attempts have recently included bicommunal work in order to improve peace talks through the initiative of a common shared heritage. In 2008, as a request by the European Union and Commission and with the support of the United Nations Development Programme Partnership for the Future (UNDP-PFF), a body politically accepted by both communities was requested to coordinate, implement, and lead a group of experts of Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots [70]. To move towards peace talks through the cultural heritage of Cyprus, the Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage was established. Its aim was to provide a mutually acceptable mechanism and measures for the preservation, maintenance, restoration, and protection of a handful of immovable heritage sites and buildings. In 2009, an “Advisory Board for the Preservation, Physical Protection and Restoration of the Immovable Cultural Heritage of Cyprus” was then established by the leaders of both communities to facilitate the protection and preservation in a non-political manner [71]. On their website and technical reports, the work phases, work methodology, selected and implemented projects are explained. The advisory committee provided a ranking to prioritize which monuments at both sides of the island are to be assessed and included. Their decisions as indicated in the report were “taken in line with the agreed principles and the task attributed by the two leaders” [71] (p. 6). While this initiative is considered to be a participatory conservation through the inclusion of architects, city planners, archaeologists, etc., it does not state anywhere the community involvement of people and their role to identify and prioritize their needs and values, which may inspire a broad authenticity based on cultural contexts. The initiative, which has the good intention to involve heritage management as a tool to bring justice to heritage sites and peace talks still follows the agreed-upon principles of the leaders and the mission of the UNDP and continues to relate cultural significance to the exclusive domain of experts and a top-down approach, which stresses the physical protection and the materialist approach to dealing with heritage management. This negates the main attributes of built heritage and its continuity in time and contributes to the museology of these sites further.

One last issue to elucidate is how coming to terms with the assessment of authenticity is problematic in the case of the church, where the expectation of respect for the cultural values of built heritage in areas of conflict is not realistic in practice. For instance, the Brussels (1874) draft of the international agreement concerning “the Laws and Customs of War” declares in article 8 that, in times of war, “all seizure or destruction of, or willful damage to […] historic monuments, works of art and science should be made the subject of legal proceedings by the competent authorities” [72]. The idea of respect and protection in times of wars and conflicts enforced by the several agreements is ineffective, as no action takes place against those who violate cultural properties until they are captured after the damage has occurred. The notion of respecting cultural property is a myth when people are at war with each other, especially when it is based on ethnic or religious differences. Cases around the world still show that when conflicts are based on religious and ethnic motives, dealing with built heritage becomes complex and difficult to implement, as evidenced in this account:

“It is clear that in settings where there had been ethnic cleansing cultural and religious heritage was often violently contested. Here heritage was more frequently a source of conflict and organized aggression, particularly during the rebuilding of religious structures, with their function as clear markers of identity—the very reason they had been destroyed in the first place [55] (p. 282).”

Although governments have obligations towards heritage management in signed international agreements, in times of conflict, these may be compromised. Respecting the laws regarding the protection of built heritage in times of war does not carry the obligation of protecting people’s valuables, especially when buildings stand for the collective memory of the “other”. Governments would not risk violating agreements to shade the authenticity of built heritage belonging to the other but may disregard their values through neglect.

Given the above discussion, one can continue to question if the Agios Synesios Church, which continues to be in use by its original users, is less or more authentic than other churches claimed to be more significant on the island. Whose approach is more authentic, the Greek Cypriots, who have stayed in their homes and continued their practices and who have sustained their existence and their lives in the church, or the experts who decide through their heritage management approaches what is authentic and what is not?

These questions and many others that will surface in time, showing that the determination of authenticity will continue to be shaped by a relativistic attitude and approach and that the intent of the Nara Document and the application of the concept of authenticity is more difficult than expected in areas of conflicts. Although this article shows that the application of authenticity is difficult given the changing context of the present life of communities and, in some cases, through conflicts, it does not invite dropping it completely, as some others suggest (see [73]). On the contrary, the article considers authenticity, if considered specifically through policy makers and adjusted in an inclusive manner, to be a tool to justice that helps to safeguard minorities and less-considered cultural heritage sites around the world by embracing continuity of use as a means of protection.

5. Conclusions

In this article, we have argued that the coming to terms with authenticity according to the pre and revised Nara Documents is a difficult task and that ambiguity still remains in relation to heritage management, especially in contexts with political conflicts. This critique is derived from the lack of mechanisms and clear guidelines considering the wider context and settings of built heritage as social, physical, and political drawn from the Nara Document and the Operational guidelines of UNESCO, and the scholarly literature is growing on this matter. While many studies emphasise the cultural and contextual specificity of built heritage, including its spiritual and intangible aspects, this is more critical in cases with religious importance, as in the case of the Greeks in Rizokarpaso village. The church that might have been of less significance in comparison to other churches in Cyprus—in terms of its physical and other associated values—attains a higher value due to its association with conflict. Serge Brammertz et al. argue that regardless of the architectural and heritage value a building may possess, being a religious institution will add spiritual value for a collective community and “needs to be taken into account when considering the depth of the harm committed when such structures are destroyed, damaged or desecrated” [74] (p. 130).

In terms of heritage conservation, it is clear that the conditions of authenticity cannot be considered as a fixed aspect inherent in the material quality of built heritage but are rather “attributed by people and through human appreciation” [75] (p. 54). The universal value of a built heritage is not something statically inherent but is based on judgments by individuals or communities with various backgrounds, can be negotiated according to the perspectives that they offer, and is changeable. This issue tends to be absent within the consideration of heritage management experts, where the scientific and objective approach still dominates.

On the basis of this argument, we call for an approach to heritage management that is centred on authenticity that embraces change through continuity of use, which can unfold the relation between people and their sites. As seen with the Agios Synesios Church, forced cultural change and the negative effects of conflict increase the emphasis on values associated with religious practice. Therefore, changes are faced through continuity of use against dominant forces that seek to determine social practices. The recognition that conservation is an active act based on various cultural codes and relations would open up new dialogues and approaches towards the future.

This article suggests that heritage studies in areas of conflict should revisit the conditions of authenticity in a more dynamic way in relation to minorities, with dedicated mechanisms and guidelines. This suggestion has been based on the case of the Agios Synesios Church. Although the article focuses on victims from one side of this continuing conflict, it does not ignore the fact that coming to terms with authenticity on the other side of the island is also difficult, since the Turkish Cypriots’ built heritage has been left unused by their original users or by the Greek Cypriot community.

Accordingly, the study invites further work on understanding authenticity from a comparative point of view, including more cases showing the different attitudes towards religious heritage on both sides of the island. The bond between authenticity and context could be further studied through quantitative research that includes a survey of a larger number of people projecting their feeling towards the changing context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S.; H.Y. and Y.H.; methodology, Y.S.; H.Y. and Y.H.; validation, Y.S.; H.Y. and Y.H.; formal analysis, Y.S.; H.Y. and Y.H.; investigation, Y.S.; H.Y. and Y.H.; resources, Y.S.; H.Y. and Y.H.; data curation, Y.S.; H.Y. and Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S.; H.Y and Y.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.S.; and H.Y.; visualization, H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bevan, R. The Destruction of Memory-Architecture at War; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanovic, B. The City and Death. In Writing Out of Yugoslavia, Balkan Blues; Labon, J., Heim, H.M., Eds.; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1995; pp. 37–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cunliffe, E. Remote Assessments of Site Damage: A New Ontology. Int. J. Herit. Digit. Era 2014, 3, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. The Nara Document on Authenticity; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1994; Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/nara-e.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2019).

- ICOMOS. NARA + 20: On Heritage Practices, Cultural Values, and the Concept of Authenticity; ICOMOS: Nara, Japan, 2014; Available online: http://www.japan-icomos.org/pdf/nara20_final_eng.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2019).

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide05-en.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- ICOMOS. The Venice Charter: International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1964; Available online: http://www.icomos.org/charters/venice.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2019).

- Jokilehto, J. Viewpoints: The Debate on Authenticity. ICCROM Newsl. 1995, 21, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Assi, E. Searching for the Concept of Authenticity: Implementation Guidelines. J. Archit. Conserv. 2000, 6, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starn, R. Authenticity and Historic Preservation: Towards an Authentic History. Hist. Hum. Sci. 2002, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. Authenticities: Past and Present. CRM J. Herit. Steward. 2008, 5, 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1972; Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Boccardi, G. Authenticity in the Heritage Context: A Reflection beyond the Nara Document. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2018, 10, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. The Phenomenon of Place. Archit. Assoc. Q. 1976, 8, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. On Reading Heidegger. In Theorizing A New Agenda for Architecture: An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965–1995; Nesbitt, K., Ed.; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 442–447. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation Concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1976; Available online: http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13133&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- ICOMOS. Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban. Areas (Washington Charter); ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1987; Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/towns_e.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2019).

- UNESCO. Vienna Memorandum on World Heritage and Contemporary Architecture—Managing the Historic Urban. Landscape; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/2005/whc05-15ga-inf7e.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Australia ICOMOS. The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance: The Burra Charter; Australia ICOMOS: Burwood, Australia, 2013; Available online: https://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Khalaf, R.W. The Reconciliation of Heritage Conservation and Development: The Success of Criteria in Guiding the Design and Assessment of Contemporary Interventions in Historic Places. Int. J. Archit. Res. Archnet IJAR 2015, 9, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Marrying the Old with the New in Historic Urban Landscapes. In Managing Historic Cities; Van Oers, R., Haraguchi, S., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life; Penguin Books: Harmondsworth, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, K.; Mkono, M.; David, M.; Stella, E. Are you for real?! Tourists’ reactions to four replica cave sites in Europe. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kaygalak, S.; Usta, Ö.; Günlü, E. Mardin’de Turizm Gelişimi ile Otantik Olgusu Arasındaki İlişkinin Sosyolojik Açıdan Değerlendirilmesi [In Turkish]. Turiz. Araştırmaları Derg. 2015, 24, 237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulding, C. The commodification of the past, postmodern pastiche, and the search for authentic experiences at contemporary heritage attractions. Eur. J. Mark. 2000, 34, 835–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. The Past is a Foreign Country—Revisited; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygen, Z. International Heritage and Historic Building Conservation: Saving the World’s Past; Routledge and Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UNESDOC. The Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and Its Two (1954 and 1999) Protocols; UNESDOC: Hague, The Netherlands, 2010; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187580 (accessed on 5 March 2020).

- Khalaf, R.W. A viewpoint on the reconstruction of destroyed UNESCO Cultural World Heritage Sites. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 261–274. [Google Scholar]

- De Cesari, C. World Heritage and Mosaic Universalism: A view from Palestine. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2010, 10, 299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, R.; Shohat, E. De-Eurocentrizing cultural studies: Some proposals. In Internationalizing Cultural Studies: An Anthology; Abbas, A., Nguyet, E.J., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 481–498. [Google Scholar]

- Legnér, M. Post-conflict reconstruction and the heritage process. J. Archit. Conserv. 2018, 24, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Labadi, S. A review of the global strategy for a balanced, representative and credible world heritage list 1994–2004. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2005, 7, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. Whose heritage? Un-settling ‘the heritage’, re-imagining the post-nation. Third Text 1999, 13, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Beyond “Preserving the Past for the Future”: Contemporary Relevance and Historic Preservation. CRM J. Herit. Steward. 2011, 8, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Saifi, Y. Role of universities in preserving cultural heritage in areas of conflict. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, I. Is the Truth Down There?: Cultural Heritage Conflict and the Politics of Archaeological Authority. Public Hist. Rev. 2006, 13, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, H. Contested Cultural Heritage: A Selective Historiography. In Contested Cultural Heritage; Silverman, H., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chotzakoglou, C.G. Religious Monuments in Turkish-Occupied Cyprus; Museum of the Holy Monastery of Kykkos: Lefkosia, Cyprus, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchese, V. Famagusta from a Latin Perspective: Venetian Heraldic Shields and Other Fragmentary Remains. In Medieval and Renaissance Famagusta, Studies in Architecture, Art and History; Peter, W., Edbury, W.P., Walsh, M.J.K., Coureas, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- Yüceer, H. The effects of conflict on religious heritage sites in Northern Cyprus. Econ. Della Cult. 2012, 22, 279–286. [Google Scholar]

- Yüceer, H. Protection of abandoned churches in Northern Cyprus: Challenges for reuse. In Protecting Cultural Heritage in Times of Conflict; Lambert, S., Rockwell., C., Eds.; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2012; pp. 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Frangeskou, M.; Hadjilyr, A.-M. The Maronites Of Cyprus; The Press and Information Office: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reyhan, S. Transitions in the Ottoman Waqf’s traditional building upkeep and maintenance system in Cyprus during the British colonial era (1878–1960) and the emergence of selective architectural conservation practices. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 512–527. [Google Scholar]

- Prio, Cyprus Center. Rizokarpasso. Prio, Cyprus Center. Available online: http://www.prio-cyprus-displacement.net/default.asp?id=617 (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Farmaki, A.; Altinay, L.; Bott, D. Politics and sustainable tourism: The case of Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunsoy, E.; Hannam, K. Conflicting Perspectives of Residents in the Karpaz Region of Northern Cyprus towards Tourism Development. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2012, 9, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpar Atun, R.; Hassina, N.; Olgaç, Ö. Envisaging sustainable rural development through ‘context-dependent tourism’: Case of northern Cyprus. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 1715–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnis, R. Historic Cyprus: A Guide to Its Towns and Villages, Monasteries and Castles; Orage Press: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Mystagogy Resource Center. The International Orthodox Christian Ministry of John Sanidopoulos. Saint Synesios of Karpasia in Cyprus, 26 May 2015. Available online: https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2015/05/saint-synesios-of-karpasia.html. (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Walasek, H. Cultural heritage and memory after ethnic cleansing in post-conflict Bosnia-Herzegovina. Int. Rev. Red Cross 2019, 101, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herscher, A. Warchitectural Theory. J. Archit. Educ. 2008, 61, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Language and Symbolic Power; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D. National Deconstruction: Violence, Identity and Justice in Bosnia; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Malkki, L. Purity and Exile: Violence, Memory, and National Cosmology among Hutu Refugees in Tanzania; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jokilehto, J. Considerations on authenticity and integrity in world heritage context. City Time 2006, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S. Experiencing Authenticity at Heritage Sites: Some Implications for Heritage Management and Conservation. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2009, 11, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A. Authenticity in connection to traditional maintenance practices: Sacred living heritage sites of Sri Lanka. In Revisiting Authenticity in the Asian Context; Sweet, J., Wijesuriya, G., Eds.; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2014; pp. 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Jigyasu, R. Considerations on authenticity in post-disaster recovery of cultural heritage: Case studies from India. In Revisiting Authenticity in the Asian Context; Sweet, J., Wijesuriya, G., Eds.; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2014; pp. 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. Cultural effects of authenticity: Contested heritage practices in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 21, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, H.J.; Smeets, R. Authenticity, Value and Community Involvement in Heritage Management under the World Heritage and Intangible Heritage Conventions. Herit. Soc. 2013, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, J. Urban World Heritage Sites and the problem of authenticity. Cities 2009, 26, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnce Güney, Y.; Yüceer, H. Appropriation of Church Buildings in Northern Cyprus. Online J. Art Des. 2021, 9, 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinou, C.M.; Demetriou, O.; Hatay, M. Conflicts and Uses of Cultural Heritage in Cyprus. J. Balkan East. Stud. 2012, 14, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifi, Y.; Yüceer, H. Maintaining the Absent Other: The re-use of religious heritage sites in conflicts. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP-PFF. The Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage-Cyprus; United Nation Development Programme-Partnership for the Future; UNDP-PFF: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2008; Available online: https://www.cy.undp.org/content/cyprus/en/home/operations/projects/partnershipforthefuture/study-of-cultural-heritage-in-the-northern-part-of-cyprus.html (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- UNDP-PFF. Report-The Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage; United Nations Development Programme-Partnership for the Future; UNDP-PFF: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2015; Available online: https://www.cy.undp.org/content/cyprus/en/home/library/partnershipforthefuture/the-technical-committee-on-cultural-heritage--2015-.html (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- ICRC. Laws and Treaties Protecting Cultural Property 1874 Brussels Declaration. 1874. Available online: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/INTRO/135 (accessed on 1 May 2019).

- Khalaf, R.W. World Heritage on the Move: Abandoning the Assessment of Authenticity to Meet the Challenges of the Twenty-First Century. Heritage 2021, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammertz, S.; Hughes, K.C.; Kipp, A.; Tomljanovi, W.B. Attacks against Cultural Heritage as a Weapon of War: Prosecutions at the ICTY. J. Int. Crim. Just. 2016, 14, 1143–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadi, S. UNESCO, Cultural Heritage, and Outstanding Universal Value: Value-Based Analyses of the World Heritage and Intangible Cultural Heritage Conventions; Altamira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).