Evaluation of the Factors that Promote Improved Experience and Better Outcomes of Older Adults in Intermediate Care Setting

Abstract

1. Introduction

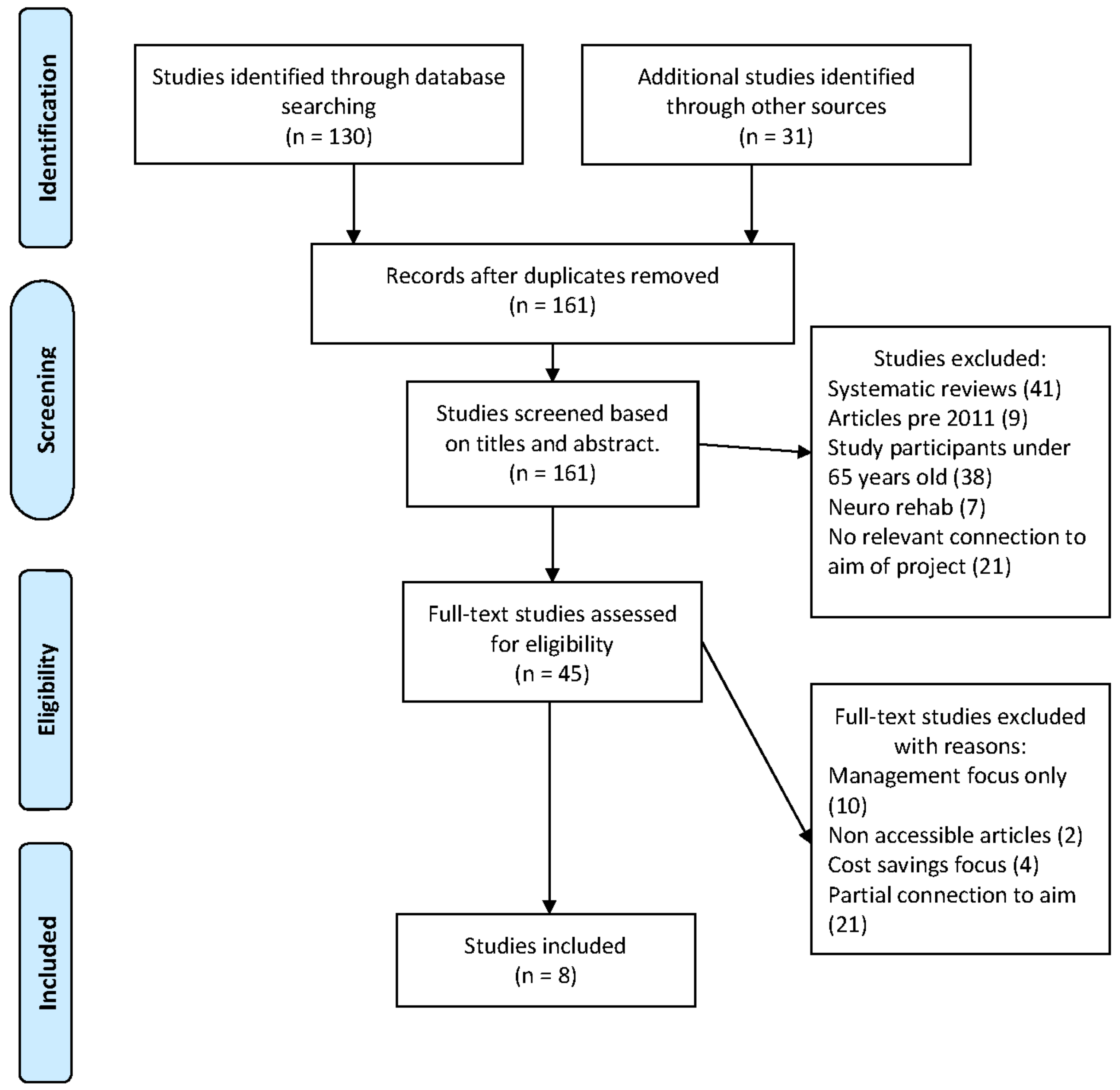

2. Method

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Themes

3.2. Communicating with Patients

3.3. Patient Participation

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Intermediate Care Including Reablement. Quality Standard 173. 2018. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs173/resources/intermediate-care-including-reablement-pdf-75545659227589 (accessed on 18 March 2019).

- Brooks, N. Intermediate care rapid assessment support service: An evaluation. Br. J. Commun. Nurs. 2002, 7, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. National Service Framework for Older People. 2001. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/quality-standards-for-care-services-for-older-people (accessed on 3 March 2019).

- National Audit of Intermediate Care Summary Report. Assessing Progress in Services for Older People Aimed at Maximizing Independence and Reducing Use of Hospitals. 2015. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58d8d0ffe4fcb5ad94cde63e/t/58f08efae3df28353c5563f3/1492160300426/naic-report-2015.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Ebrahimi, V. Reablement: Shifting Minds. In Reablement Services in Health and Social Care; Ebrahimi, V.A., Chapman, H.M., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2018; pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tuntland, H.; Aaslund, M.K.; Espehaug, B.; Forland, O.; Kjeken, I. Reablement in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 145. Available online: https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-015-0142-9 (accessed on 2 March 2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiee, P.; Glendinning, C. Organisation and delivery of home care re-ablement: What makes a difference? Health Soc. Care Commun. 2011, 19, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innes, K.; Crawford, K.; Jones, T.; Blight, R.; Trenham, C.; Williams, A.; Griffiths, D.; Morphet, J. Transdisciplinary care in the emergency department: A qualitative analysis. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2016, 25, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. Five Year Forward View. 2014. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2019).

- Oliver, D.; Foot, C.; Humphries, R. Making Our Health and Care Systems Fit for and Ageing Population. 2014. Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/making-health-care-systems-fit-ageing-population-oliver-foot-humphries-mar14.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Steventon, A.; Deeny, S.; Friebel, R.; Gardner, T.; Thorlby, R. Briefing: Emergency Hospital Admissions in England: Which May be Avoidable and How? The Health Foundation: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.health.org.uk/publications/emergency-hospital-admissions-in-england-which-may-be-avoidable-and-how (accessed on 24 March 2019).

- National Health Service (NHS) England. A & E Attendances and Emergency Admissions February 2019 Statistical Commentary. 2019. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/03/Statistical-commentary-Feb-2019.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2019).

- Jones, J.; Carroll, A. Hospital admission avoidance through the introduction of a virtual ward. Br. J. Commun. Nurs. 2014, 19, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health Service (NHS) England. Safe, Compassionate Care for Frail Older People Using an Integrated Care pathway: Practical Guidance for Commissioners, Providers and Nursing, Medical and Allied Health Professional Leaders. 2014. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/safe-comp-care.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2019).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Intermediate Care Including Reablement (NG74). 2017. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng74/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-4600707949 (accessed on 20 December 2018).

- Beecroft, C.; Booth, A.; Rees, A. The Research Process in Nursing, 7th ed.; Gerrish, K., Lathlean, J., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Br. Med. J. 2009, 8, 336–341. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/339/bmj.b2535.full?view=long&pmid=19622551 (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- Ellis, P. Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Kings Fund. Community Health Services Explained. 2019. Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/community-health-services-explained#comments-top (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Andrews, J.; Manthorpe, J.; Watson, R. Involving older people in intermediate care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 46, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Audit of Intermediate Care Summary Report-England. Assessing Progress in Services Aimed at Maximising Independence and Reducing use of Hospitals. 2017. Available online: https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/nhsbn-static/NAIC%20(Providers)/2017/NAIC%20England%20Summary%20Report%20-%20upload%202.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP (Qualitative) Checklist. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Birkeland, A.; Tuntland, H.; Forland, O.; Jakobsen, F.F.; Langeland, E. Interdisciplinary collaboration in reablement-A qualitative study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2017, 10, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjelle, K.M.; Tuntland, H.; Forland, O.; Alvsvag, H. Driving forces for home-based reablement; a qualitative study of older adults’ experiences. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2017, 25, 1581–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjelle, K.M.; Skutle, O.; Forland, O.; Alvsvag, H. The reablement team’s voice: A qualitative study of how an integrated multidisciplinary team experiences participation in reablement. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2016, 9, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokstad, K.; Skovdahl, K.; Landmark, B.T.H.; Haukelien, H. Ideal and reality; Community healthcare professionals’ experiences of user-involvement in reablement. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2019, 27, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moe, A.; Brataas, H.V. Patient influence in home-based reablement for older persons: Qualitative research. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 736. Available online: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12913-017-2715-0 (accessed on 9 February 2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, A.; Rosewilliam, S.; Soundy, A. Shared decision-making within goal-setting in rehabilitation: A mixed-methods study. Clin. Rehabil. 2019, 33, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilde, A.; Glendinning, C. ‘If they’re helping me then how can I be independent?’ The perceptions and experience of users of home-care re-ablement services. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2012, 20, 583–590. [Google Scholar]

- Randstrom, K.B.; Wengler, Y.; Asplund, K.; Svedlund, M. Working with ‘hands off’ support: A qualitative study of multidisciplinary teams’ experiences of home rehabilitation for older people. Int. J. Old. People Nurs. 2014, 9, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M. Communication skills 1: Benefits of effective communication for patients. Nurs. Times 2017, 113, 18–19. Available online: https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/assessment-skills/communication-skills-1-benefits-of-effective-communication-for-patients/7022148.article (accessed on 21 April 2019).

- Nursing & Midwifery Council. The Code Professional Standards of Practice and Behaviour for Nurses, Midwives and Nursing Associates. 2018. Available online: https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/ (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Miller, L. Effective communication with older people. Nurs. Stand. 2002, 17, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, A.; Nancarrow, S.A.; Enderby, P. Mechanisms to enhance the effectiveness of allied health and social care assistants in community-based rehabilitation services: A qualitative study. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2015, 23, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angel, S.; Frederiksen, K.N. Challenges in achieving patient participation: A review of how patient participation is addressed in empirical studies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Patient Experience in Adult NHS Services: Improving the Experience of Care for People Using Adult NHS Services (CG138). 2012. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg138/chapter/1-Guidance#enabling-patients-to-actively-participate-in-their-care (accessed on 22 January 2019).

| Author | Was There a Clear Statement of the Aims of the Research? | Is a Qualitative Methodology Appropriate? | Was the Research Design Appropriate to Address the Aims of the Research? | Was the Recruitment Strategy Appropriate to the Aims of the Research? | Was the Data Collected in a Way that Addressed the Research Issue? | Has the Relationship between Researcher and Participants been Adequately Considered? | Have Ethical Issues been Taken into Consideration? | Was the Data Analysis Sufficiently Rigorous? | Is there a Clear Statement of Findings? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birkeland et al. [23] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X Leaders present in the group may have affected discussion. | √ | √ | √ |

| Hjelle et al. [24] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X There may have been bias as sample number was limited and the study leader may have ‘cherry picked’ participants who experienced positive outcomes therefore not a representative sample. | √ | √ | √ |

| Hjelle et al. [25] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Jokstad et al. [26] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | X Project leaders known to participants which may have impacted on responses. Conversely this may have made for a more comfortable setting for participants. | √ | √ | √ |

| Moe et al. [27] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Rose et al. [28] | √ | * | √ | √ Limited by small sample size | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Wilde and Glendinning [29] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Randstrom et al. [30] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Author and Country | Aims and Objectives | Participants | Design | Findings | Implications for practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birkeland et al. [23] Norway. | To clarify how interdisciplinary collaboration in reablement worked in a Norwegian context. | 33 participants. 9 physiotherapists 7 occupational therapists 9 nurses 4 social educators 3 auxiliary nurses 1 social worker. | Qualitative study Focus groups of 4–6 people lasting 1–1.5 h. | Interdisciplinary collaboration is dependent on patients having the opportunity to identify their own goals. Staff considered interdisciplinary working enriching and positive and reciprocal professional learning was valued. When organisational barriers are removed new knowledge opens. Interdisciplinary working dependent on motivation. | Professional communication skills - training. Shared inclusive planning and decision making. Interdisciplinary collaboration can improve professional performance and satisfaction. Time is important |

| Hjelle et al. [24] Norway. | To describe how older adults in Norway experience participation in reablement. | 8 participants. 4 men 4 women Age range 64–92 years. | Qualitative descriptive study. | Goals identified by patients are key to positive outcomes. Patient determination and responsibility are intrinsic motivational factors and a driving force to achieving goals set. Team co-operation | Patient centred goal setting with professionals are key to positive outcomes. Teamwork. Engaging the patient. |

| Hjelle et al. [25] Norway. | To explore and describe how an integrated multidisciplinary team in Norway experienced participation in reablement. | 2 focus groups-all female. Group 1. 6 healthcare professionals with a bachelor’s degree; 1 physiotherapist 2 occupational therapists 1 social educator 2 nurses. Group 2. 8 home care personnel without formal healthcare education; 2 auxiliary nurses 6 assistants. | Qualitative phenomenological hermeneutic study. | Different way of thinking. Collaboration is motivating. Patient goals are essential. Patients were active recipients rather than passive recipients. Formal and informal meetings facilitate professional collaboration and communication | Inclusive person-centred goal setting within a collaborative integrated multidisciplinary team can affect care delivery and encourage active patient engagement. Communication skills training. |

| Jokstad et al. [26] Norway. | Explore healthcare professionals’ experiences of user involvement in reablement. | 6 nurse assistants 6 nurses 3 physiotherapists 3 occupational therapists Focus Group 1 = 7 participants Focus Group 2 = 7 participants reduced to 5 due to sickness Focus Group 3 = 6 participants. | Explorative descriptive qualitative approach | Challenging adjustment from ‘doing for’ to ‘doing with’ users. Modifications in attitudes and traditional practice. Diverse ability to commit to what user involvement requires. Time invested during the initial phase contributes to optimising outcomes of reablement. Values, attitudes and practices challenged due to structural, cultural and personal factors. | Protected venues for interdisciplinary meetings key to developing and maintaining interdisciplinary competences. Flexibility and professional adjustment promote the ideal of transforming ‘user involvement into practice’. Time invested with patients in the initial phase of reablement pathway contribute to encouraging patient involvement. |

| Moe et al. [27] Norway. | To gain knowledge about conversation processes and patient influence in formulating patients’ goals | 8 patients cases chosen. 5 women 3 men Ages 67–90 years old. Mean age = 80 years All patients lived in their own private homes. Professional team = occupational therapist, physiotherapist, nurse and care workers. | Qualitative naturalistic enquiry based on purposive sampling. | Information sharing and assessment tools provide a baseline for assessment. Communication skills and leadership encourage patient participation at initial assessment. Trusting relationships can promote active patient participation. Mapping of resources and patients’ needs help formulate patient objectives. Introductions are an important baseline in developing interactive conversations. | Interactive and inclusive goal setting with patients is key. Competence in professional’s communication skills to encourage patient understanding and engagement. Information sharing. |

| Rose et al. [28] England. | To assess the extent of shared decision making within goal setting meetings and explore patient reported factors that influenced their participation to shared decision making about their goals. | Patients with a frailty syndrome defined by BGS eligible for Phase 1 (P1) 40 participants selected—20 patients from each setting (community/inpatient) 13 rehab assistants, 6 physiotherapists and 5 occupational therapists approached for consent to participate in the study, 3 rehab assistants declined. | Mixed methods approach in 2 phases. Phase 1 Questionnaire. Phase 2 Qualitative data collected through semi structured interviews. | Patient participation increased if staff appeared to listen during interactions. With information patients are more likely to want to engage in decision making/goal setting. | Information sharing. Professionals complex communication skills. Active listening. Inclusive decision making. What is important to the patient. |

| Wilde and Glendinning [29] England. | To identify the perceptions and experiences of users of reablement services. | 34 service users and 10 carers from 5 established reablement services in England. | Qualitative study using data collected in the course of a larger mixed methods study. | Explanation of service and intermittent reminders during intervention is critically important. Lack of patient knowledge and understanding of intervention has a detrimental effect on engagement. Understanding patient and carers priorities are central to successful reablement outcomes. Demotivation and frustration can occur when patients own goals are not addressed. Communication and understanding vital to outcome of intervention. | Patient centred goal planning is an inclusive process. Clear communication in different formats shared at intervals of intervention can reinforce and re-engage patients. Including and engaging carers in the reablement goal setting phase and throughout the process can improve outcomes. Communication skills training. |

| Randstrom et al. [30] Sweden. | To explore multidisciplinary teams’ experiences of home rehabilitation for older people. | 5 focus groups covering 7 different professions. 28 participants in total. 6 physiotherapists 3 occupational therapists 5 district nurses 5 nursing assistants 1 home help 3 home help needs assessment officers 5 home help officers in charge | Descriptive qualitative study. | Team bases promote team communication Team supervision supports a restorative approach. ‘Hands off’ patient support promoted patient’s participation Planning and flexibility were considered significant to supporting person centred care. Person centred approaches, interpersonal relationships and emotional support facilitates participation during intervention. Willingness and positive attitudes to understand colleague’s contribution was conducive to supporting a patient independence. | Episodes of patient care should come from an ‘emerged whole team performance’. Communication skills training. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blendell, R.; Ojo, O. Evaluation of the Factors that Promote Improved Experience and Better Outcomes of Older Adults in Intermediate Care Setting. J 2020, 3, 20-31. https://doi.org/10.3390/j3010004

Blendell R, Ojo O. Evaluation of the Factors that Promote Improved Experience and Better Outcomes of Older Adults in Intermediate Care Setting. J. 2020; 3(1):20-31. https://doi.org/10.3390/j3010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlendell, Rona, and Omorogieva Ojo. 2020. "Evaluation of the Factors that Promote Improved Experience and Better Outcomes of Older Adults in Intermediate Care Setting" J 3, no. 1: 20-31. https://doi.org/10.3390/j3010004

APA StyleBlendell, R., & Ojo, O. (2020). Evaluation of the Factors that Promote Improved Experience and Better Outcomes of Older Adults in Intermediate Care Setting. J, 3(1), 20-31. https://doi.org/10.3390/j3010004