SWOT Analysis of Blended Learning in Public Universities of Uganda: A Case Study of Muni University

Abstract

1. Introduction

RQ1. What are the factors influencing students and lecturers’ intention to use blended learning?

RQ2. What are the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of blended learning in Muni University as one of the public universities of Uganda?

2. Related Work

2.1. Blended Learning in Uganda

2.2. Factors Influencing Students and Lecturers’ Intention to Use Blended Learning

2.2.1. Resources

2.2.2. Instructional Course Design

2.2.3. Motivation

2.2.4. Teacher Competence

2.2.5. Attitude and Values

2.2.6. Institutional Factors

2.2.7. Communication

2.2.8. Didactics

2.2.9. Course Outcomes

2.2.10. Policy

2.3. The SWOT Analysis of Blended Learning

2.3.1. Strengths

Offers Flexibility and Efficiency

Enhanced Social Interaction, Communication, and Collaboration

Cost-Effectiveness

Enhancing Learning

2.3.2. Weaknesses

Resource Intensive

Dealing with Technical Issues

Digital Divide

The Loss in a Classroom Community

Support and Training for Instructors and Learners

2.3.3. Opportunities

Extending the Reach and Mobility

Technology

2.3.4. Threats

Low Bandwidth and Unstable Internet

Unreliable Power Supply

Lack of Clear Policies and Legislation Regarding Blended Learning

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Sample Technique

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Social Demography Characteristic

4.2. Responses of Students and Lecturers’ Regarding Skills on Using Blended Learning

4.3. Factors Influencing Students and Lecturers’ Intention to Use Blended Learning

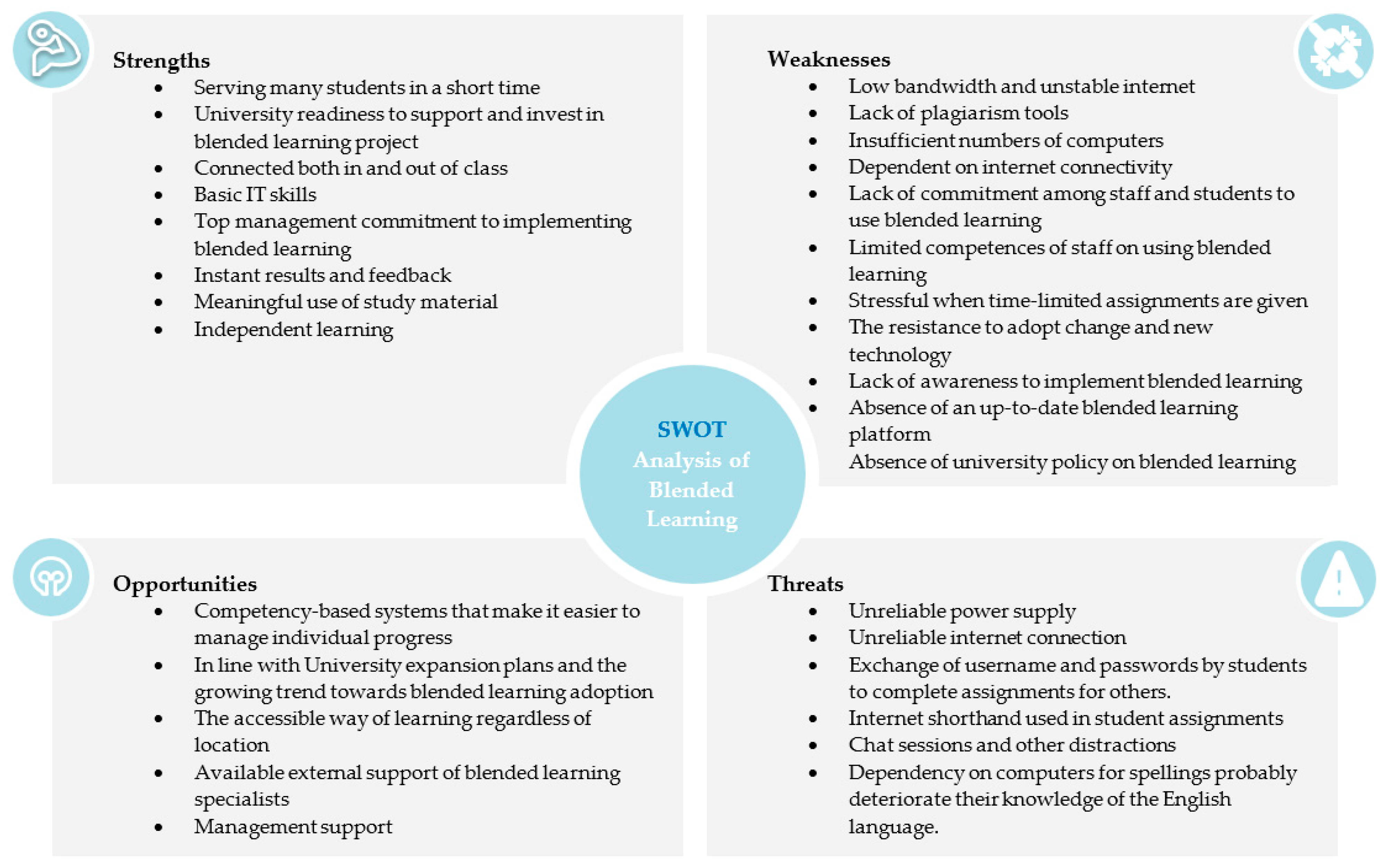

4.4. SWOT Analysis of Blended Learning at Muni University

4.4.1. Strengths of Blended Learning

4.4.2. Weaknesses of Blended Learning

4.4.3. Opportunities for Blended Learning

4.4.4. Threats to Blended Learning

5. Discussion

- ▪

- Blended learning can serve many students in a short time, thus saving students time and enhancing teaching and learning interaction between readers and students. This is in line with the work of References [6,10] who state that blended learning can connect people, actions and outcomes through technology and the interaction between learners and instructor, as well as learners with fellow scholars, may build online communities and learning exercises where they can exchange and value knowledge, thoughts, experience and other learning products. It is as well affirmed by Reference [5] where it was noted that blended learning can create dialogue outside of the classroom among students and teachers with the help of tools such as discussions, chats, and forums. This made the classroom interactions more productive through pre-work;

- ▪

- There is flexibility in the scheduling of classes. This result is logical with the work conducted by Reference [6] where it was likewise noted that blended learning combines offline and online learning;

- ▪

- With online teaching, the internet provides flexibility and efficiency in instruction and learning activities which can be conducted via videos or teleconference. It is as well confirmed by other researchers such as [4,7,8,9,48] where it was identified that blended learning increases the flexibility of learning time and place and permits flexibility and self-regulation learning among learners and teachers;

- ▪

- Instant results and feedback, meaningful use of subject material and independent learning are some of the benefits of blended learning. These findings are similar to the studies of [4,7,8,20,48] where it was found out that blended learning provides individualized learning opportunities for both scholars and lecturers thus supporting more self-determined learning.

- ⇨

- It is dependent on internet connectivity which makes it difficult to be accessed by other students and lecturers. This reaffirms the findings of earlier studies by References [18,52] who observed that slow internet accessibility makes it hard to upload course materials. It is further supported by References [5,20,49,50,51,52] who observed that poor internet speed and connectivity is a heavy challenge in blended learning implementation;

- ⇨

- Lack of plagiarism tools to monitor the character of student assignments. This result is logical with the work conducted by Reference [1] in which the researcher identified that plagiarism and credibility pose a major problem to blended learning;

- ⇨

- There is a high risk of reduced face-to-face social interactions with blended learning mode. This outcome is consistent with the study conducted by Reference [53] where it was noted that in blended learning, learners may not only experience the isolation of lively social interaction with peers but also incapable to connect with their instructors;

- ⇨

- The insufficient number of computers per student is also another challenge. This finding is reported in other earlier studies conducted by References [5] that added that the process of conducting online tests is entirely dependent on expensive technology that may or may not be available to all off-campus students.

- ⇨

- Very limited staff capacity to implement blended learning. This finding is described in other earlier studies conducted by References [49,50,51]. It is also consistent with References [52,53] who argued that learners should be provided with computer-related and technological skills to succeed in a blended learning setting because some students from different social, economic background might be facing difficulties in accessing or adapting to the online learning component in blended learning due to lack of IT skills and knowledge;

- ⇨

- Some of the weaknesses found include; dependent on internet connectivity, lack of commitment among students and readers to use blended learning, stressful when time-special assignments are granted, resistance by some students and lecturers’ to adopt new technology, lack of awareness to implement blended learning, absence of an up-to-date blended learning platform, and absence of university policy on blended learning.

- ✕

- It is in line with university expansion plans and the growing trend towards blended learning adoption. This outcome is consistent with the study conducted by Reference [25] in which they observed that the development of e-learning is in line with the university’s expansion strategies so that it can reach more students;

- ✕

- Availability of external support of blended learning specialists. This finding is also reported in another earlier study conducted by Reference [25] where they opined that external support will help the institution in training staff on professional competencies of using e-learning which is a great opportunity;

- ✕

- Respondents also identified the accessible means of learning regardless of location as an opportunity. This result is logical with the work conducted by Reference [11] where they found that using a single method of teaching and learning limits the range and number of people who can access the information. If such kind of information can be posted on a blended learning system, learners can easily access them at any time and location. It is as well affirmed by References [5,20] where it was observed that uniform content can be presented to students and international students are appreciative of online assignments. Cucciare, Weingardt, and Villafranca [12] added that when complementary training contents are provided on blended learning, they can reach many learners;

- ✕

- Finally, the respondents also identified management support—competency-based systems that make it easier to manage individual progress as some of the opportunities for blended learning.

- An unreliable power supply is a major threat to the implementation of blended learning. This reconfirmed the findings of earlier studies by Reference [25,49,50,51,52,53] where they identified a concern of inconsistent power supply, which makes it hard to rely on online components of blended learning. It is as well affirmed by Reference [58] where they noted that lack of power played a heavy role in the digital divide in Tanzania and Uganda thus hindering the implementation of e-learning;

- Unreliable internet connection is also a threat. This result is logical with the work conducted by Reference [25] in which they found that, for successful implementation of blended learning, there should be stable internet connectivity but in many developing and least developing countries, the internet is unreliable and the bandwidth is low. It is as well affirmed by References [1,18,52,57] who identified poor internet speed and connectivity as a threat to blended learning.

- Chat sessions while multitasking online proved to be a distraction. This reconfirms the findings of Reference [5] who took note that chat sessions while multitasking online is a distraction to students.

- Exchange of student username and passwords to complete assignments for others. This outcome is consistent with the study conducted by Reference [5] where they found that exchange of student ID and passwords to complete assignments for others is common with blended learning platforms if not properly monitored.

- Dependence on computers for spellings deteriorate students and lecturers’ English language knowledge. This is supported by Reference [5] who observed students who depend on computers for spelling checking have their English knowledge deteriorated.

- Respondents also identified internet shorthand used in student assignments and lack of intrinsic motivation of students as some of the threats to blended learning. This is in line with the work of Reference [5] who urged that internet shorthand like acronyms, emoticons and playful spelling is used by a student in assignments, online essay exams and quizzes.

6. Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oweis, T.I. Effects of Using a Blended Learning Method on Students’ Achievement and Motivation to Learn English in Jordan: A Pilot Case Study. Educ. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 7425924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauk, S.; Šćepanović, S.; Kopp, M. Estimating Students’ Satisfaction with Web-Based Learning System in Blended Learning Environment. Educ. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 731720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.amanet.org/training/articles/blended-learning-opporunities-45.aspx (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Ricky, N.Y.-K.; Rechell, L.Y.-S.; Kwan-Keung, N.; Ivan, L.K.-W. A Study of Vocational and Professional Education and Training (VPET) Students and Teachers’ Preferred Support for Technology-Based Blended Learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Symposium on Educational Technology, Hong Kong, China, 27–29 June 2017; pp. 268–271. [Google Scholar]

- Rossett, A.; Frazee, R.V. Blended Learning Opportunities; White Paper; American Management Association: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Available online: http://www.amanet.org/blended/insights.htm (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Azizan, F.Z. Blended Learning in Higher Education Institution in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the Regional Conference on Knowledge Integration in ICT 2010, Kolej Universiti Islam Antarabangsa Selangor (KUIS), Putrajaya, Malaysia, 1–2 June 2010; 2010; pp. 454–466. [Google Scholar]

- Winterstein, T.; Greiner, F.; Schlaak, H.F.; Pullich, L. A Blended-Learning Concept for Basic Lectures in Electrical Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Education and e-Learning Innovations, Sousse, Tunisia, 1–3 July 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, A.; Lilly, L.; Kurt, T. Testing the professor’s hypothesis: Evaluating a blended-learning approach to distance education. J. Public Aff. Educ. 2006, 12, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshabalala, M.; Ndeya-Ndereya, C.; van der Merwe, T. Implementing Blended Learning at a Developing University: Obstacles in the way. Electron. J. E-Learn. 2014, 12, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, M.B.; Borokhovski, E.; Schmid, R.F.; Tamim, R.M.; Abrami, P.C. A meta-analysis of blended learning and technology use in higher education: From the general to the applied. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2014, 26, 87–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H. Building effective blended learning programs. Educ. Technol. 2003, 46, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cucciare, M.A.; Weingardt, K.R.; Villafranca, S. Using blended learning to implement evidence-based psychotherapies. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2008, 15, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snipes, J. Blended Learning: Reinforcing Results. 2005. Available online: http://www.clomedia.com/talent.php?pt=search (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- González-Gómez, D.; Jeong, J.S.; Rodríguez, D.A.; Cañada-Cañada, F. Performance and Perception in the Flipped Learning Model: An Initial Approach to Evaluate the Effectiveness of a New Teaching Methodology in a General Science Classroom. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2016, 25, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoffrey, N.M. Challenges of Implementing Quality Assurance Systems in Blended Learning in Uganda: The Need for an Assessment Framework. HURIA J. 2014, 18, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul, W.N.; Othman, J.; Warris, S.N. Blended Learning in Higher Education: An Overview. E-Acad. J. UiTMT 2016, 5, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Owston, R.; York, D.; Murtha, S. Student perceptions and achievement in a university blended learning strategic initiative. J. Internet High. Educ. 2013, 18, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, N.M.; Isa, N.; Daud, N.M.N.; Aziz, A.A. Lecturers’ Experiences in Implementing Blended Learning Using i-Learn. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Science and Social Research, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 5–7 December 2010; pp. 580–585. [Google Scholar]

- Muni University. Mission. Vision and Muni Core Values. 2015. Available online: https://muni.ac.ug/about-muni/mission-vision-core-values.html (accessed on 13 February 2019).

- Hande, S. Strengths Weaknesses Opportunities and Threats of Blended Learning: Students’ Perceptions. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 2014, 4, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basheka, B.; Lubega, T.; Baguma, R. Blended learning approaches and the teaching of monitoring and evaluation programmes in African universities: Unmasking the UTAMU approach. Afr. J. Public Aff. 2016, 9, 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, A.N.L.; Yang, I. Academics and learners’ perceptions on blended learning as a strategic initiative to improve the student learning experience. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 87, 4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.S.; Yao, A.Y.T. An Empirical Evaluation of Critical Factors Influencing Learner Satisfaction in Blended Learning: A Pilot Study. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 1667–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozelius, P.; Hettiarachchi, E. Critical Factors for Implementing Blended Learning in Higher Education. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. Educ. 2017, 6, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Kintu, J.M. A SWOT analysis of the integration of e-learning at a university in Uganda and a university in Tanzania. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2015, 24, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Bonk, C.J. The future of online teaching and learning in higher education: The survey says. Educ. Q. 2006, 29, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael, C.; Mtebe, J.S. Instructor support services: An inevitable critical success factor in blended learning in higher education in Tanzania. Int. J. Educ. Dev. Using Inf. Commun. Technol. 2016, 12, 123–138. [Google Scholar]

- Heinerichs, S.; Pazzaglia, G.; Gilboy, M.B. Using Flipped Classroom Components in Blended Courses to Maximize Student Learning. Athl. Train. Educ. J. 2016, 11, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, R.; Rouse, E. Social presence—Connecting pre-service teachers as learners using a blended learning model. Stud. Success 2016, 7, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, H.J.; Brush, T.A. Student perceptions of collaborative learning, social presence, and satisfaction in a blended learning environment: Relationships and critical factors. Comput. Educ. 2008, 51, 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.A.; Diloreto, M. The Effects of Student Engagement, Student Satisfaction, and Perceived Learning in Online Learning Environments. Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Prep. 2016, 11, 1-0. [Google Scholar]

- King, S.; Arnold, K. Blended learning environments in higher education: A case study of how professors make it happen. Mid-West. Educ. Res. 2012, 25, 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Holenko, M.; Hoić-Božić, N. Using online discussions in a blended learning course. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2008, 3, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Slevin, J. E-learning and the transformation of social interaction in higher education. Learn. Media Technol. 2008, 33, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snježana, B. Factors that Influence Academic Teacher’s Acceptance of E-Learning Technology in Blended Learning Environment; E-Learning-Organizational Infrastructure and Tools for Specific Areas; Guelfi, A., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-953-51-0053-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gautreau, C. Motivational Factors Affecting the Integration of a Learning Management System by Faculty, California State University Fullerton. J. Educ. Online 2011, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Renzi, S. Differences in University Teaching after Learning Management System Adoption: An Explanatory Model Based on Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mihhailova, G. E-learning as an internationalization strategy in higher education: Lecturer’s and student’s perspective. Balt. J. Manag. 2006, 1, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Vaughan, N.D. Blended Learning in Higher Education: Framework, Principles, and Guidelines; John Wiley Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kansanen, P. Teaching as teaching-studying-learning interaction. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 1999, 43, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alammary, A.; Sheard, J.; Carbone, A. Blended learning in higher education: Three different design approaches. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2014, 30, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shand, K.; Glassett-Farrelly, S.; Victoria, C. Principles of course redesign: A model for blended learning. In Proceedings of the Society for Information Technology Teacher Education International Conference 2016, Savannah, GA, USA, 21 March 2016; pp. 378–389. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, J.; Maor, D.; Herrington, J. Authentic online learning: Aligning learner needs, pedagogy, and technology. Issues Educ. Res. 2013, 23, 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Diep, A.-N.; Zhu, C.; Struyven, K.; Blieck, Y. Who or what contributes to student satisfaction in different blended learning modalities? Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 48, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.R. Blended learning systems: Definitions, current trends, and future directions. In The Handbook of Blended Learning: Global Perspectives, Local Designs; Bonk, C.J., Graham, C.R., Eds.; Pfeiffer: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.A.; Strickland, A.J.; Gamble, J.E. Crafting and Executing Strategy-Concepts and Cases, 15th ed.; McGraw Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, R.G. Strategic development and SWOT analysis at the University of Warwick. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 152, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, N. Perspectives on blended learning in higher education. Int. J. E-Learn. 2007, 6, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kajumbula, R.; Tibaingana, A. Incorporating Relationship Marketing as a Learner Support Measure in Quality Assurance Policy for Distance Learning at Makerere University; Makerere University: Kampala, Uganda, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Aguti, J.N. Distance Education in Uganda. Paper Delivered at the Workshop on the Support for Distance Education Students at Hotel Africana Kampala Uganda, (unpublished). 2000.

- Bbuye, J. Distance Education in Uganda, Development, Practices, and Issues; Makerere University: Kampala, Uganda, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Oroma, J.O.; Ali, G.; Mbabazi, B.P. Towards Personalized Learning Environment in Universities in Developing Countries through Blended Learning: A Case of Muni University. Sch. World Int. Refereed J. Arts Sci. Commer. 2018, 6, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Okaz, A.A. Integrating Blended Learning in Higher Education. In Proceedings of the 5th World Conference on Learning, Teaching and Educational Leadership, WCLTA 2014, Prague, Czech Republic, 29–30 October 2014; pp. 600–603. [Google Scholar]

- Motschnig-Pitrik, R.; Standl, B. Person-centered technology enhanced learning: Dimensions of added value. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 29, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebowitz, J.; Frank, M. Knowledge Management and E-Learning; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cojocariu, V.-M.; Lazar, I.; Nedeff, V.; Lazar, G. The SWOT analysis of e-learning educational services from the perspective of their beneficiaries. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 1999–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbabazi, B.P.; Ali, G. Evaluation of E-Learning Management Systems by Lecturers and Students in Ugandan Universities: A Case of Muni University. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2016, 5, 9529–9536. [Google Scholar]

- Ndume, V.; Tilya, F.N.; Twaakyondo, H. Challenges of adaptive eLearning at higher learning institutions: A case study in Tanzania. Int. J. Comput. ICT Res. 2008, 2, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Demiray, U. E-Learning Practices, Cases on Challenges Facing E-Learning and National Development: Institutional Studies and Practices, I; Anadolu University: Eskisehir, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S/N | Skills of Blended Learning | Students | Lecturers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| 1 | Need training skills | 48.1% | 51.9% | 52.0% | 48.0% |

| 2 | Can do enrollment/self-enrollment | 86.2% | 13.8% | 84.0% | 16.0% |

| 3 | Can access and upload course materials | 80.4% | 19.6% | 92.0% | 8.0% |

| 4 | Can submit/set assignment, tests, and quizzes | 81.5% | 18.5% | 88.0% | 12.0% |

| 5 | Can participate in online discussions | 67.7% | 32.3% | 88.0% | 12.0% |

| 6 | Can send a course feedback message | 66.1% | 33.9% | 72.0% | 28.0% |

| No | Factors | VL | L | A | H | VH | Mean | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Accessibility within and outside the university | 12.7 | 6.3 | 20.1 | 21.7 | 39.2 | 3.68 | 1.378 |

| 2 | Positive attitude towards using blended learning | 5.3 | 9.0 | 26.5 | 31.2 | 28.0 | 3.68 | 1.133 |

| 3 | Knowledge and skills | 2.1 | 9.5 | 31.7 | 32.8 | 23.8 | 3.67 | 1.011 |

| 4 | Favorable learning environment | 1.6 | 12.2 | 31.7 | 34.9 | 19.6 | 3.59 | 0.989 |

| 5 | Perceived usefulness | 5.8 | 12.7 | 24.3 | 39.2 | 18.0 | 3.51 | 1.014 |

| 6 | Perceived quality content | 2.6 | 11.1 | 34.9 | 35.4 | 15.9 | 3.51 | 0.976 |

| 7 | Awareness and adaptation | 6.3 | 7.9 | 37.0 | 26.5 | 22.2 | 3.50 | 1.114 |

| 8 | Good user interface | 9.5 | 15.9 | 27.5 | 23.8 | 23.3 | 3.35 | 1.262 |

| 9 | Perceived ease of usage | 7.9 | 15.9 | 32.3 | 25.4 | 18.5 | 3.31 | 1.176 |

| 10 | Perceived resources | 7.9 | 15.9 | 29.6 | 31.2 | 15.3 | 3.30 | 1.148 |

| 11 | Self-management of learning | 5.3 | 18.5 | 34.9 | 25.4 | 15.9 | 3.28 | 1.102 |

| 12 | Previous experience | 14.8 | 14.8 | 29.1 | 24.3 | 16.9 | 3.14 | 1.285 |

| No | Strengths | SD | D | N | A | SA | Mean | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Serving many students in a short time | 0.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 44.0 | 48.0 | 4.36 | 0.757 |

| 2 | University readiness to support and invest in blended learning project | 4.2 | 4.8 | 24.3 | 28.6 | 38.1 | 3.92 | 1.093 |

| 3 | Connected both in and out of class | 5.8 | 6.9 | 14.8 | 39.2 | 33.3 | 3.87 | 1.127 |

| 4 | Basic IT skills | 1.6 | 7.4 | 20.6 | 44.4 | 25.9 | 3.86 | 0.943 |

| 5 | Top management commitment to implementing blended learning | 7.4 | 9.5 | 14.3 | 36.5 | 32.3 | 3.77 | 1.211 |

| 6 | Instant results and feedback | 5.8 | 11.6 | 20.6 | 36.5 | 25.4 | 3.65 | 1.139 |

| 7 | Meaningful use of study material | 3.7 | 7.4 | 25.9 | 46.6 | 16.4 | 3.65 | 0.965 |

| 8 | Independent learning | 4.8 | 12.2 | 23.8 | 37.6 | 21.7 | 3.59 | 1.100 |

| No | Weaknesses | SD | D | N | A | SA | Mean | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Low bandwidth and unstable internet | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 14.8 | 67.7 | 4.33 | 1.180 |

| 2 | Lack of plagiarism tools to monitor the quality of student assignments | 6.3 | 3.2 | 7.9 | 22.2 | 60.3 | 4.27 | 1.147 |

| 3 | Insufficient numbers of computers | 5.8 | 5.8 | 11.1 | 28.6 | 48.7 | 4.08 | 1.164 |

| 4 | Dependent on internet connectivity | 11.6 | 7.9 | 10.1 | 20.6 | 49.7 | 3.89 | 1.400 |

| 5 | Lack of commitment among staff and students to use blended learning | 7.4 | 13.8 | 13.2 | 26.5 | 39.2 | 3.76 | 1.301 |

| 6 | Limited competencies of staff on using blended learning | 8.5 | 12.7 | 19.0 | 28.6 | 31.2 | 3.61 | 1.277 |

| 7 | Stressful when time-limited assignments are given | 9.0 | 14.3 | 18.0 | 36.5 | 22.2 | 3.49 | 1.236 |

| 8 | The resistance of some students and lecturers’ to adopt change and new technology | 10.6 | 11.1 | 22.8 | 30.7 | 24.9 | 3.48 | 1.270 |

| 9 | Lack of awareness to implement blended learning | 6.9 | 15.9 | 24.3 | 29.1 | 23.8 | 3.47 | 1.210 |

| 10 | Absence of an up-to-date blended learning platform | 10.1 | 19.6 | 18.0 | 24.9 | 27.5 | 3.40 | 1.340 |

| 11 | Absence of university policy on blended learning | 9.5 | 18.5 | 25.9 | 30.7 | 15.3 | 3.24 | 1.199 |

| No | Opportunities | SD | D | N | A | SA | Mean | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Competency-based systems that make it easier to manage individual progress | 3.2 | 6.9 | 8.5 | 47.6 | 33.9 | 4.02 | 0.994 |

| 2 | In line with university expansion plans and the growing trend towards blended learning adoption | 3.2 | 3.2 | 21.7 | 40.7 | 31.2 | 3.94 | 0.971 |

| 3 | The accessible way of learning regardless of location | 5.3 | 4.8 | 18.0 | 37.0 | 34.9 | 3.92 | 1.093 |

| 4 | Available external support of blended learning specialists | 3.7 | 7.4 | 15.9 | 40.2 | 32.8 | 3.91 | 1.056 |

| 5 | Management support | 4.2 | 6.3 | 13.8 | 47.1 | 28.6 | 3.89 | 1.026 |

| No | Threats | SD | D | N | A | SA | Mean | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unreliable power supply | 3.7 | 2.1 | 9.0 | 13.8 | 71.4 | 4.47 | 1.003 |

| 2 | Unreliable internet connection | 3.2 | 4.2 | 9.0 | 20.6 | 63.0 | 4.36 | 1.025 |

| 3 | Exchange of username and passwords by students to complete assignments for others. | 4.8 | 7.4 | 15.3 | 28.6 | 43.9 | 3.99 | 1.151 |

| 4 | Internet shorthand used in student assignments | 5.8 | 8.5 | 18.0 | 30.2 | 37.6 | 3.85 | 1.185 |

| 5 | Chat sessions and other distractions | 4.8 | 12.7 | 18.0 | 27.5 | 37.0 | 3.79 | 1.205 |

| 6 | Dependence on computers for spellings probably deteriorate their knowledge of the English language. | 6.3 | 10.1 | 18.0 | 30.7 | 34.9 | 3.78 | 1.209 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali, G.; Buruga, B.A.; Habibu, T. SWOT Analysis of Blended Learning in Public Universities of Uganda: A Case Study of Muni University. J 2019, 2, 410-429. https://doi.org/10.3390/j2040027

Ali G, Buruga BA, Habibu T. SWOT Analysis of Blended Learning in Public Universities of Uganda: A Case Study of Muni University. J. 2019; 2(4):410-429. https://doi.org/10.3390/j2040027

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Guma, Bosco Apparatus Buruga, and Taban Habibu. 2019. "SWOT Analysis of Blended Learning in Public Universities of Uganda: A Case Study of Muni University" J 2, no. 4: 410-429. https://doi.org/10.3390/j2040027

APA StyleAli, G., Buruga, B. A., & Habibu, T. (2019). SWOT Analysis of Blended Learning in Public Universities of Uganda: A Case Study of Muni University. J, 2(4), 410-429. https://doi.org/10.3390/j2040027