Ecological Park with a Sustainable Approach for the Revaluation of the Cultural and Historical Landscape of Pueblo Libre, Peru—2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Methodological Scheme

2.2. Place of Study

2.3. Climatology

2.4. Flora and Fauna

3. Results

3.1. Project Location

3.2. Master Plan

3.3. Proposed Spaces

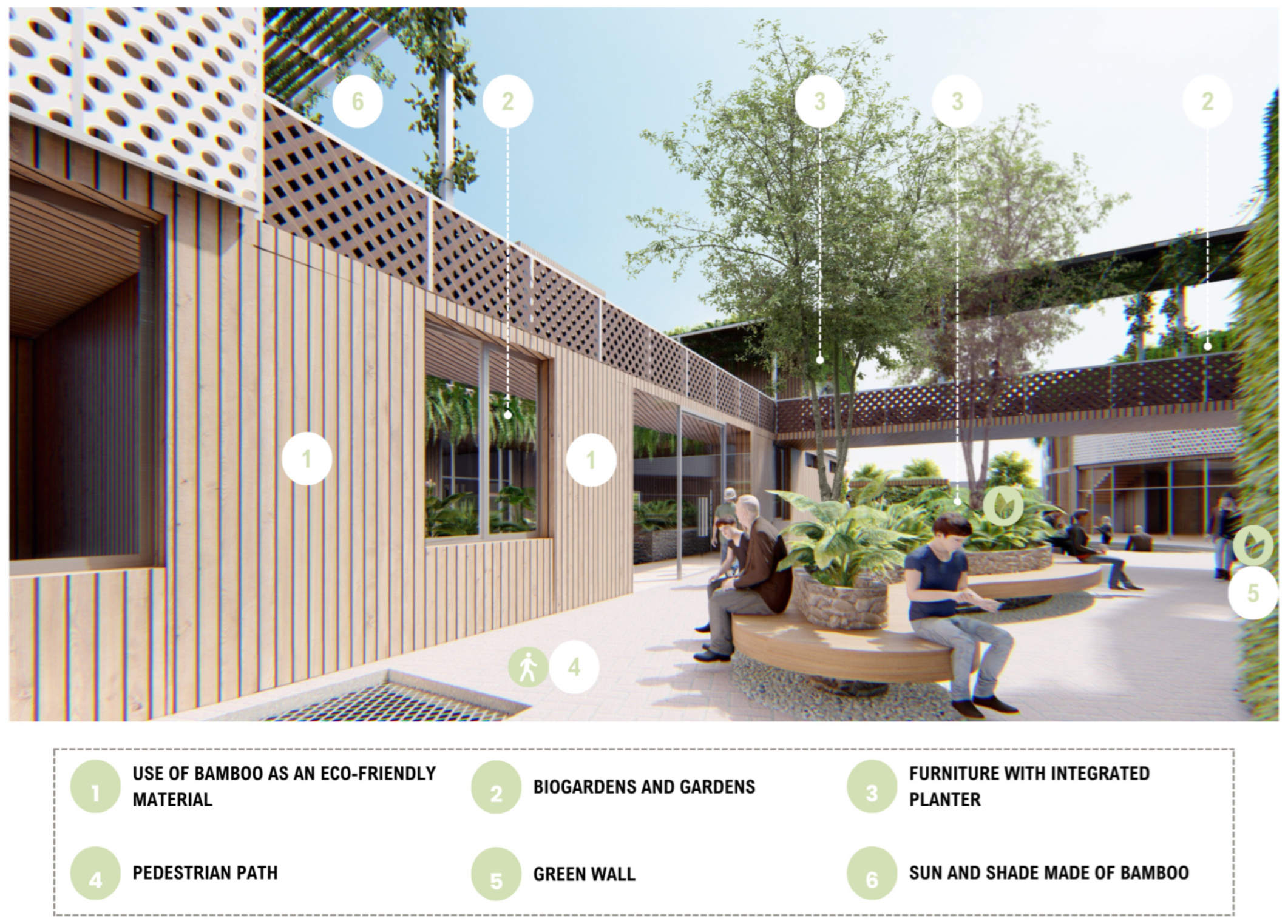

3.3.1. Community Library

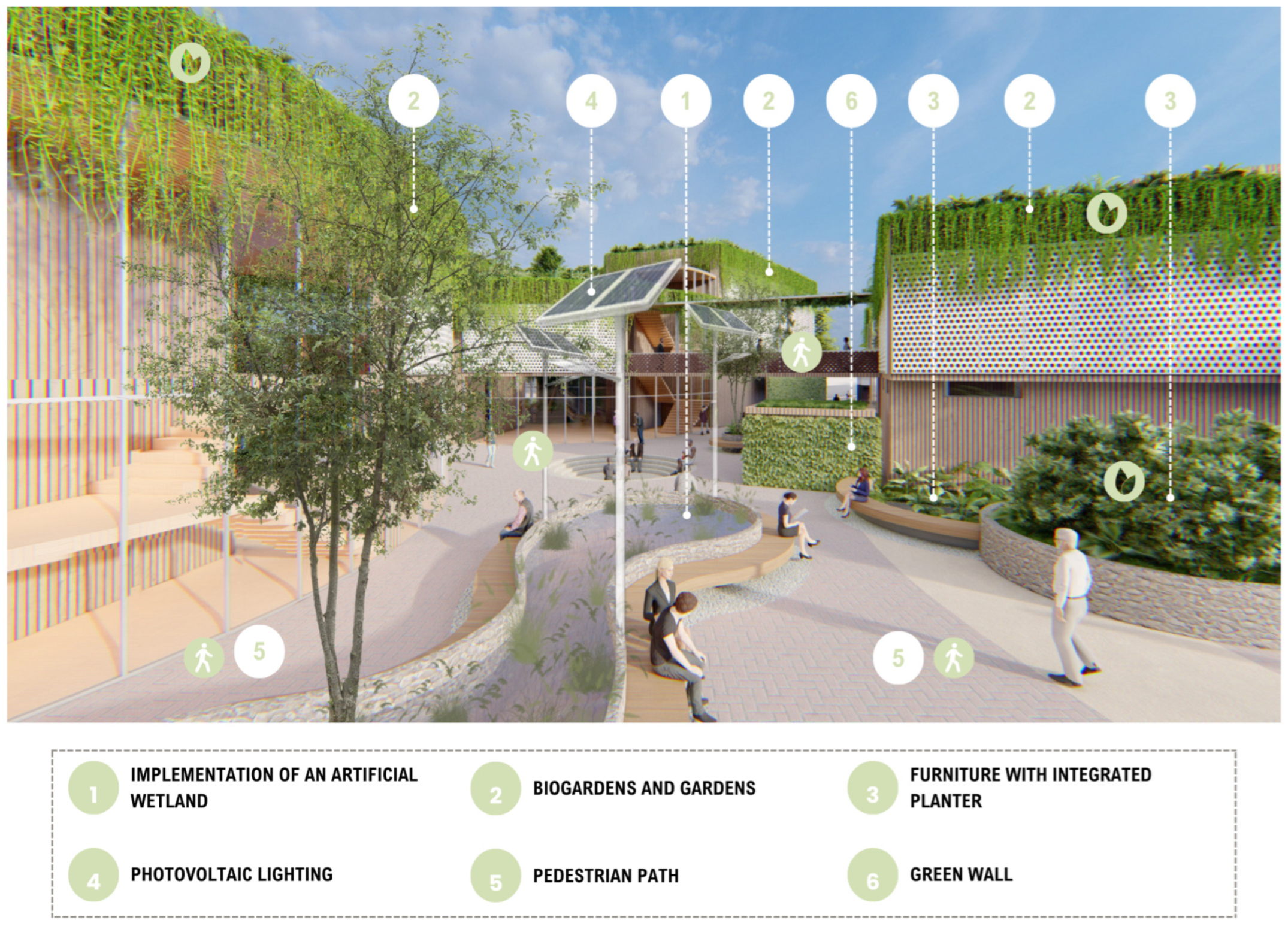

3.3.2. The Cultural Center (Centro Cultural) and Citizenship Resource Center (CREC)

3.3.3. Cultural Esplanade

3.3.4. Ecological Park

3.4. Materiality

3.5. Strategies Applied to the Project

3.5.1. Photovoltaic Lighting

3.5.2. Artificial Wetland

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Definición. (s. f.). Ministerio de Cultura. Available online: https://www.cultura.gob.es/planes-nacionales/planes-nacionales/paisaje-cultural/definicion.html (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Sierra Nevada: Conservación de la Biodiversidad. (s. f.). Vicepresidencia Tercera del Gobierno. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/parques-nacionales-oapn/red-parques-nacionales/parques-nacionales/sierra-nevada/conservacion-biodiversidad.html (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Mancilla, D.; Robledo, S.; Esenarro, D.; Raymundo, V.; Vega, V. Green Corridors and Social Connectivity with a Sustainable Approach in the City of Cuzco in Peru. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centro Nacional de Planeamiento Estratégico (CEPLAN). Análisis del Crecimiento y Expansión Urbana a Nivel Nacional y su Impacto a Nivel Regional. 2023. Available online: https://geo.ceplan.gob.pe/uploads/Analisis_crecimiento_expansion_urbana.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Yávar, J. Paisaje y arquitectura: Parque Ecológico de St Jacques, Protección y desarrollo de ecosistemas por Atelier des Paysages Bruel-Delmar. ArchDaily en Español. Available online: https://www.archdaily.cl/cl/624611/paisaje-y-arquitectura-parque-ecologico-de-st-jacques-proteccion-y-desarrollo-de-ecosistemas-por-atelier-des-paysages-bruel-delmar (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Voces por el Clima. (s. f.). Voces por el Clima. Available online: https://www.minam.gob.pe/vocesporelclima/ (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Municipalidad de Miraflores. Parque BIcentenario [Internet]. Available online: https://www.miraflores.gob.pe/parque-bicentenario/ (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Restrepo, L.A.V. Del parque urbano al parque sostenible: Bases conceptuales y analíticas para la evaluación de la sustentabilidad de parques urbanos. Norte Gd. Geogr. J. 2009, 43, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, L. Paisajes Culturales: El Parque Patrimonial como Instrumento de Revalorización y Revitalización del Territorio. Redalyc.org, 2004. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=29901302 (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Lima Entre las Ciudades Menos Verdes de Latinoamérica [Internet]. Espacio Verde, 2024. Available online: https://www.espacioverde.pe/lima-entre-las-ciudades-menos-verdes-de-latinoamerica/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Subgerencia de Gestión Ambiental. Análisis de la Situación Actual de las Áreas Verdes y Arbolado Urbano [Internet]. Available online: https://smia.munlima.gob.pe/uploads/documento/84a137f7fc9e56d6.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Portal iPerú. Distrito de Pueblo Libre de la Provincia de Lima, Región Lima. Portal iPerú. Available online: https://www.iperu.org/distrito-de-pueblo-libre-provincia-de-lima (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Marin, H.M. Ponen Freno a las Ciclovías: Decenas de Kilómetros han Desaparecido y Lucen Abandonadas en Lima y Callao|Informe. El Comercio Perú. Available online: https://elcomercio.pe/lima/transporte/ponen-freno-a-las-ciclovias-cuantos-kilometros-de-recorrido-han-desaparecido-en-lima-y-callao-informe-decenas-de-kilometros-han-desaparecido-y-lucen-abandonadas-en-lima-y-callao-transporte-ciclistas-noticia/ (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Municipalidad Distrital de Pueblo Libre. (s. f.). Plan de Desarrollo Concertado de Pueblo Libre 2010–2021. Portal de Transparencia Estándar. Available online: https://www.transparencia.gob.pe/enlaces/pte_transparencia_enlaces.aspx?id_entidad=10230&id_tema=5&ver= (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Plan Estratégico Institucional (PEI) 2017–2019. (s. f.). Informes y Publicaciones—Organismo Supervisor de las Contrataciones del Estado—Plataforma del Estado Peruano. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/osce/informes-publicaciones/292376-plan-estrategico-institucional-pei-2017-2019 (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- Estudio de Microzonificación Sísmica y Análisis de Riesgo en la Zona de Estudio Ubicada en el Distrito de Pueblo Libre—Tomo III. (s. f.). Municipalidad de Pueblo Libre. Available online: https://portal.muniplibre.gob.pe/microzonificacion/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Augusto, A.S.F. La Infraestructura para Discapacitados Motrices en los Atractivos Turísticos del Distrito de Pueblo Libre y su Relación con la Promoción Turística de la Municipalidad. 2018. Available online: https://repositorio.usmp.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12727/4342 (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Cultura Pueblo Libre [Internet]. Gob.pe. Available online: https://portal.muniplibre.gob.pe/cultura-pueblo-libre/ (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- ytuqueplanes. (s/f). Pueblo Libre. Y tú que Planes? Available online: https://www.ytuqueplanes.com/destinos/lima/ciudad-de-lima/pueblo-libre (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Municipalidad de Pueblo Libre. (s/f). Pueblo Libre «Capital del Bicentenario». Municipalidad de Pueblo Libre. Available online: https://portal.muniplibre.gob.pe/pueblo-libre-capital-del-bicentenario (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Güere, R.; Liz, J. Centro Cultural en Lima Norte. Bachelor’s Thesis, En Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC), Lima, Peru, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municipalidad Distrital de Pueblo Libre. (2020). Diagnóstico de Brachas de Infraestructura y de Acceso a Servicios en el Distrito de Pueblo Libre. PMI 2021–2023. Available online: https://portal.muniplibre.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/DIAGNOSTICO-DE-BRECHAS-PMI-2021-2023.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Comité Distrital de Seguridad Ciudadana Pueblo Libre. Propuesta Plan de Acción Distrital de Seguridad Ciudadana 2023. 2023. Available online: https://portal.muniplibre.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/PADSC-2023-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Abello-Hurtado Lisson, D.O. Plano de Sectorización de Pueblo Libre—2023. Available online: https://portal.muniplibre.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/2023-MAPA-RIESGO-II.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Alfredo, G.R. Planeamiento Estratégico del Distrito de Pueblo Libre. Available online: https://tesis.pucp.edu.pe/repositorio/handle/20.500.12404/4548 (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- Francisco, R.M.A.J. De la Obsolescencia al Aprovechamiento del Suelo Público Urbano. Renovación Urbana en la Zona Monumental de Pueblo Libre. Available online: https://tesis.pucp.edu.pe/repositorio/handle/20.500.12404/25370 (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- [MD PUEBLO LIBRE 150121] Plan de Prevención y Reducción del Riesgo de Desastres de la Municipalidad Distrital de Pueblo Libre 2020–2022. (Biblioteca SIGRID). (s. f.). Available online: https://sigrid.cenepred.gob.pe/sigridv3/documento/11970 (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Comité Distrital de Seguridad Ciudadana de Pueblo Libre. Plan Local de Seguridad Ciudadana y Convivencia Social del Distrito de Pueblo Libre 2014. Municipalidad Distrital de Pueblo Libre. 2014. Available online: https://portal.muniplibre.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Compact-Digital-2.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Michaelaschloegl. (s. f.-b). Datos Climáticos y Meteorológicos Históricos Simulados para Lima. Meteoblue. Available online: https://www.meteoblue.com/es/tiempo/historyclimate/climatemodelled/lima_per%c3%ba_3936456 (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Municipalidad Distrital de Pueblo Libre. (s.f.). Recursos Turísticos. Available online: https://portal.muniplibre.gob.pe/turismo-pueblo-libre/recursos-turisticos/ (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Yvette. Las Lomas de Amancaes Desaparecen Bajo el Avance de Invasiones en Lima. Noticias Ambientales. Available online: https://es.mongabay.com/2018/01/peru-lomas-de-amancaes-invasiones-lima/#:~:text=Las%20Lomas%20de%20Amancaes%20desaparecen%20bajo%20el%20avance%20de%20invasiones%20en%20Lima,-por%20Yvette%20Sierra&text=El%20%C3%A1rea%20natural%20ha%20sido,potable%20la%20ponen%20en%20peligro (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Penagos, J.L.O. Notas Sobre la Fauna de Lima | Blog de Juan Luis Orrego Penagos. Available online: http://blog.pucp.edu.pe/blog/juanluisorrego/2011/06/23/notas-sobre-la-fauna-de-lima/#:~:text=Entre%20los%20mam%C3%ADferos%2C%20tenemos%20a,posible%20encontrar%20lisas%20y%20bagres (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Gamez, M.J. Objetivos y Metas de Desarrollo Sostenible—Desarrollo Sostenible. Desarrollo Sostenible. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/objetivos-de-desarrollo-sostenible/ (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- United Nations. (s. f.). Los Espacios Verdes: Un Recurso Indispensable para Lograr una Salud Sostenible en las Zonas Urbanas|Naciones Unidas. Available online: https://www.un.org/es/chronicle/article/los-espacios-verdes-un-recurso-indispensable-para-lograr-una-salud-sostenible-en-las-zonas-urbanas (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Jerez, J.C. El rol de las Bibliotecas Públicas Comunitarias en el Desarrollo Socio-Económico de Nicaragua. Redalyc.org, 2007. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=16114070001 (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Viviana, T.O. El rol de los Centros Culturales. Available online: https://repository.urosario.edu.co/items/7ff0c5e2-c514-4eba-8b62-25aca95d0dce (accessed on 29 April 2023).

- adBicentenario. Feria Bicentenario «El país que Imaginamos»: Herramientas para Construir Ciudadanía. Bicentenario del Perú. Available online: https://bicentenario.gob.pe/feria-bicentenario-el-pais-que-imaginamos-herramientas-para-construir-ciudadania/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Ramos Ponte, F.J. Explanada Cultural Urbana para Fomentar la Revitalización de Espacios en el Distrito del Callao Hacia el 2021. Red de Repositorios Latinoamericanos, 2019. Available online: https://repositorioslatinoamericanos.uchile.cl/handle/2250/3210035 (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Cisa. Parque Ecológico—Cisambiental. Cisambiental. Available online: https://www.cisambiental.com/parque-ecologico/#:~:text=Entre%20los%20principales%20beneficios%20de,de%20especies%20en%20la%20naturaleza (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Estimaciones de Captura de los Parques y Emisiones de CO2 Vehicular en Tijuana, B.C. (s. f.). Available online: https://www.colef.mx/posgrado/tesis/20141174/ (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Gómez Salés, H.J.P.; Rodríguez Chumacero, R.C.; Ramal Montejo, R. El Bambú: Una Solución Ecológica Sustentable Como Material De Construcción. Rev. Cient. Inst. TZHOECOEN 2020, 12, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Segarra, M.; Bragança, L. El bambú como alternativa de construcción sostenible. Ext. Innov. Transf. Tecnol. 2019, 5, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octavio, I.C.U. Uso del Bambú y Su Rentabilidad Como Material de Construccion en la Ciudad de Iquitos, Loreto. 2022. Available online: http://repositorio.ucp.edu.pe/handle/UCP/2103 (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Ceccon, E.; Gómez-Ruíz, P.A. Bamboos Ecological functions on environmental services and productive ecosystems restoration. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2019, 67, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- @Revisenergy. Conoce los beneficios de la iluminación solar. RevistaEnergía.pe. Available online: https://revistaenergia.pe/conoce-los-beneficios-de-la-iluminacion-solar/ (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Departament d’Enginyeria Electrònica, Elèctrica i Automàtica. Desarrollo de un Sistema de Iluminación Solar para el Ahorro de Energía Eléctrica en el Alumbrado Público de México. Available online: https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/667293 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Malpartida, A. Iluminación Fotovoltaica en Plazas y Parques del Puerto de ilo. Rev. Cienc. Tecnol.—Desarrollo—Ujcm 2022, 5, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, Q.Q.A. (s. f.). Diseño y Construcción de Humedal Artificial para la Recuperación de Aguas Residuales en la Población de Alcalá. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.bo/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2225-87872021000200009 (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Esenarro, D.; Vasquez, P.; Acosta-Banda, A.; Raymundo, V. Green Infrastructure as a Sustainability Strategy for Biodiversity Preservation: The Case Study of Pantanos de Villa, Lima, Peru. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, K.X.; Dehghanifarsani, L.; Amani-Beni, M. Urban engineering insights: Spatiotemporal analysis of land surface temperature and land use in urban landscape. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 92, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymundo, V.; Vargas, C.; Alcalá, C.; Marin, S.; Jaulis, C.; Esenarro, D.; Huerta, E.; Fernandez, D.; Martinez, P. Green Infrastructure as an Urban Landscape Strategy for the Revaluation of the Ite Wetlands in Tacna. Buildings 2025, 15, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esenarro, D.; Lescano, J.; Chalco, B.; Tapia, N.; Vilchez Cairo, J.; Vargas Beltran, C.; Arriola, C.; Ruiz Reyes, R. Spatial, Functional, and Constructive Analysis of the Water Resource at the Archaeological Center of Tipon, Cusco, Peru, 2023. Heritage 2024, 7, 6629–6656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | ‘Voices for the Climate’ Ecological Park | Bicentennial Park—Miraflores | St. Jacques Ecological Park |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Factor | Promotes awareness and active participation of society in environmental conservation and climate change mitigation [6]. | It is a public space accessible to everyone, which promotes social inclusion by providing a place for recreation [7]. | It actively involves residents, allowing them to contribute to the planning and development of the green space [5]. |

| Economic Factor | Attracts tourists interested in ecotourism and environmental education [6]. | Attracts visitors who wish to enjoy the natural beauty [7]. | Creation of jobs related to the planning, construction, and maintenance of the park [5]. |

| Environmental Factor | Conservation of the environment through environmental education, the promotion of sustainable practices, and the protection of natural resources [6]. | It provides habitats for local wildlife and contributes to the conservation of pollinators [7]. | Creation of a cane field for the phytoremediation of runoff water [5]. |

| Ages | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–14 | 6340 | 6341 | 12,681 |

| 15–64 | 22,735 | 28,046 | 50,781 |

| 65+ | 4190 | 6512 | 10,702 |

| Total | 33,265 | 40,899 | 74,164 |

| Species | CO2 Captured (Kg/year) per Tree | Percentage of CO2 Captured | Number of Trees | Total CO2 Captured (Kg/year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schinus molle | 182.64 | 35.87 | 10 | 1826.4 |

| Morus Alba | 58.67 | 11.52 | 3 | 176.01 |

| Schinus terebinthifolius | 74.364 | 14.60 | 10 | 743.64 |

| Jacaranda mimosifolia | 52.411 | 10.29 | 12 | 628.93 |

| Ficus carica | 56.67 | 11.13 | 3 | 170.01 |

| Caesalpinia spinosa | 25.00 | 4.91 | 5 | 125.00 |

| Prosopis pallida | 17.40 | 3.41 | 2 | 34.80 |

| Erythrina crista-galli | 22.00 | 4.32 | 6 | 132.00 |

| Bambú | 20.00 | 3.95 | 7 | 140.00 |

| Total | 509.155 | 100 | 58 | 3976.79 |

| Model | FP060A/Bifacial Monocrystalline Panel |

|---|---|

| Solar Panel Potential | 80 W |

| Illumination Radius | 8 m |

| Height | 6 m |

| Luminosity | 8000 lm |

| Free area of the ecological park | 5352.9 m2 |

| Illumination area | 201.06 m2 |

| Units of solar luminaires | 26 |

| Surface Area (m2) | Mean Water Depth (m) | Volume (m3) |

| 35 m2 | 1.1 m | 38.5 m3 |

| 1 m3 = 1000 L water | ||

| Volume (m3) | Liters of Water (L) | Total Constructed Wetland Water |

| 38.5 m3 | 1000 L | 38,500 L |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mancilla-Bravo, D.C.; Chichipe-Mondragón, V.M.; Esenarro Vargas, D.; Uribe Quiroz, C.; Calderón Huamaní, D.; Ruiz Reyes, E.; Alfaro, C.; Veliz, M. Ecological Park with a Sustainable Approach for the Revaluation of the Cultural and Historical Landscape of Pueblo Libre, Peru—2023. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7020046

Mancilla-Bravo DC, Chichipe-Mondragón VM, Esenarro Vargas D, Uribe Quiroz C, Calderón Huamaní D, Ruiz Reyes E, Alfaro C, Veliz M. Ecological Park with a Sustainable Approach for the Revaluation of the Cultural and Historical Landscape of Pueblo Libre, Peru—2023. Clean Technologies. 2025; 7(2):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7020046

Chicago/Turabian StyleMancilla-Bravo, Diego C., Vivian M. Chichipe-Mondragón, Doris Esenarro Vargas, Cecilia Uribe Quiroz, Dante Calderón Huamaní, Elvira Ruiz Reyes, Crayla Alfaro, and Maria Veliz. 2025. "Ecological Park with a Sustainable Approach for the Revaluation of the Cultural and Historical Landscape of Pueblo Libre, Peru—2023" Clean Technologies 7, no. 2: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7020046

APA StyleMancilla-Bravo, D. C., Chichipe-Mondragón, V. M., Esenarro Vargas, D., Uribe Quiroz, C., Calderón Huamaní, D., Ruiz Reyes, E., Alfaro, C., & Veliz, M. (2025). Ecological Park with a Sustainable Approach for the Revaluation of the Cultural and Historical Landscape of Pueblo Libre, Peru—2023. Clean Technologies, 7(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7020046