Rare Orbital Metastasis of Carcinoid Tumor Despite Long-Term Somatostatin Therapy: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

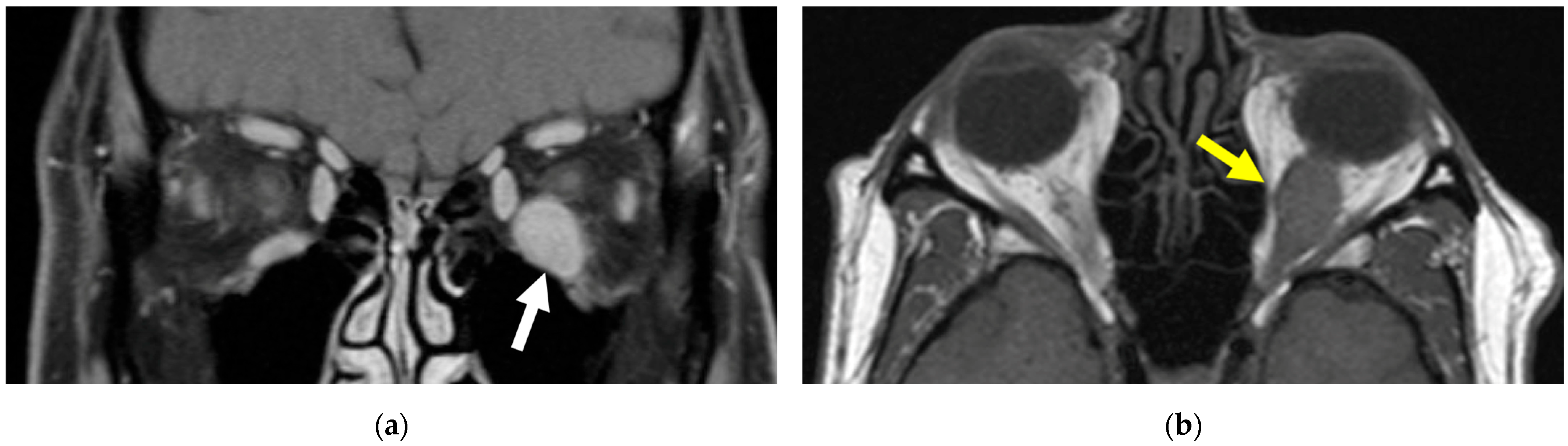

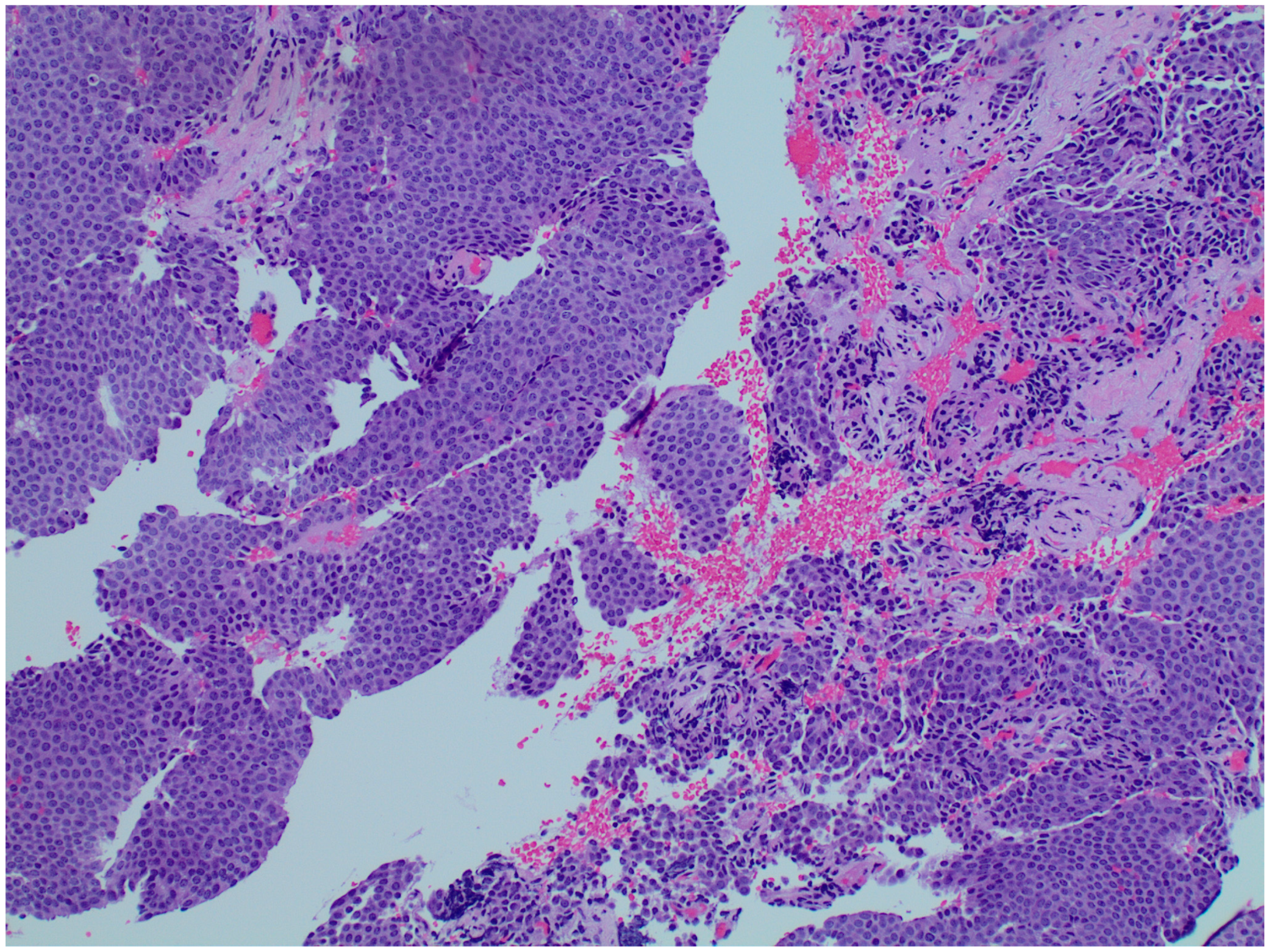

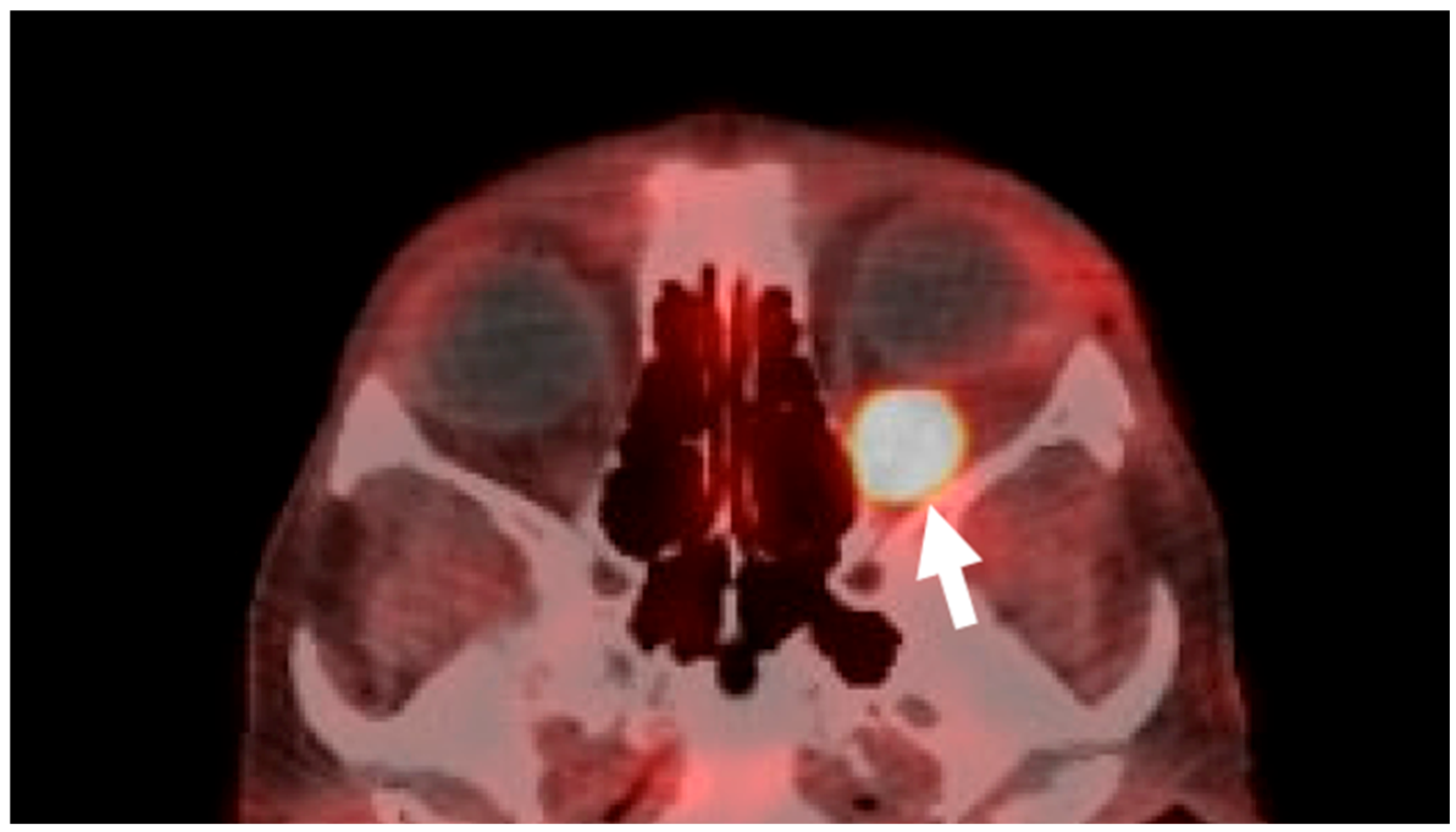

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schnirer, I.I.; Yao, J.C.; Ajani, J.A. Carcinoid—A comprehensive review. Acta Oncol. 2003, 42, 672–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou Saleh, M.; Mansoor, E.; Anindo, M.; Isenberg, G. Prevalence of Small Intestine Carcinoid Tumors: A US Population-Based Study 2012–2017. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modlin, I.M.; Lye, K.D.; Kidd, M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer 2003, 97, 934–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, M.A.; Khan, H.M.; Sabiq, F.; Agoumi, M.; Neufeld, A. Metastatic neuroendocrine tumor masquerading as orbital cysticercosis. Neuroradiol. J. 2023, 36, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T.G.; Juniat, V.; Stewart, C.; Malhotra, R.; Hardy, T.G.; McNab, A.A.; Davis, G.; Selva, D. Clinico-radiological findings of neuroendocrine tumour metastases to the orbit. Orbit 2022, 41, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, L.A.; Curragh, D.; Sia, P.I.; Selva, D. Pseudocystic appearance of an orbital carcinoid metastasis. Orbit 2020, 39, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamaleshwaran, K.K.; Joseph, J.; Upadhya, I.; Shinto, A.S. Image Findings of a Rare Case of Neuroendocrine Tumor Metastatic to Orbital Extraocular Muscle in Gallium-68 DOTANOC Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography and Therapy with Lutetium-177 DOTATATE. Indian J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 32, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiratli, H.; Uzun, S.; Tarlan, B.; Ateş, D.; Baydar, D.E.; Söylemezoğlu, F. Renal Carcinoid Tumor Metastatic to the Uvea, Medial Rectus Muscle, and the Contralateral Lacrimal Gland. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 31, e91–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turaka, K.; Mashayekhi, A.; Shields, C.L.; Lally, S.E.; Kligman, B.; Shields, J.A. A case series of neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumor metastasis to the orbit. Oman J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 4, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, D.; Shinder, R. Primary renal carcinoid metastatic to the orbit. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 31, e37–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peixoto, R.D.; Lim, H.J.; Cheung, W.Y. Neuroendocrine tumor metastatic to the orbit treated with radiotherapy. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2013, 5, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.H.; Goldner, W.S.; Benson, A.B.; Bergsland, E.; Blaszkowsky, L.S.; Brock, P.; Chan, J.; Das, S.; Dickson, P.V.; Fanta, P.; et al. Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2021, 19, 839–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustak, H.; Liu, W.; Murta, F.; Ozgur, O.; Couch, S.; Garrity, J.; Shinder, R.; Kazim, M.; Callahan, A.; Hayek, B.; et al. Carcinoid Tumors of the Orbit and Ocular Adnexa. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 37, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delpassand, E.S.; Ranganathan, D.; Wagh, N.; Shafie, A.; Gaber, A.; Abbasi, A.; Kjaer, A.; Tworowska, I.; Núñez, R. 64Cu-DOTATATE PET/CT for Imaging Patients with Known or Suspected Somatostatin Receptor-Positive Neuroendocrine Tumors: Results of the First U.S. Prospective, Reader-Masked Clinical Trial. J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, P.; McBride, A.; Ray, D.; Pulgar, S.; Ramirez, R.; Elquza, E.; Favaro, J.; Dranitsaris, G. Lanreotide vs octreotide LAR for patients with advanced gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: An observational time and motion analysis. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 25, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reccia, I.; Pai, M.; Kumar, J.; Spalding, D.; Frilling, A. Tumour Heterogeneity and the Consequent Practical Challenges in the Management of Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Cancers 2023, 15, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massironi, S.; Albertelli, M.; Hasballa, I.; Paravani, P.; Ferone, D.; Faggiano, A.; Danese, S. “Cold” Somatostatin Analogs in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Decoding Mechanisms, Overcoming Resistance, and Shaping the Future of Therapy. Cells 2025, 14, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hosalkar, H.; Meller, L.; Jalbout, N.D.E.; Shoji, M.K.; Baxter, S.L.; Kikkawa, D.O. Rare Orbital Metastasis of Carcinoid Tumor Despite Long-Term Somatostatin Therapy: A Case Report. Reports 2025, 8, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030158

Hosalkar H, Meller L, Jalbout NDE, Shoji MK, Baxter SL, Kikkawa DO. Rare Orbital Metastasis of Carcinoid Tumor Despite Long-Term Somatostatin Therapy: A Case Report. Reports. 2025; 8(3):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030158

Chicago/Turabian StyleHosalkar, Hritika, Leo Meller, Nahia Dib El Jalbout, Marissa K. Shoji, Sally L. Baxter, and Don O. Kikkawa. 2025. "Rare Orbital Metastasis of Carcinoid Tumor Despite Long-Term Somatostatin Therapy: A Case Report" Reports 8, no. 3: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030158

APA StyleHosalkar, H., Meller, L., Jalbout, N. D. E., Shoji, M. K., Baxter, S. L., & Kikkawa, D. O. (2025). Rare Orbital Metastasis of Carcinoid Tumor Despite Long-Term Somatostatin Therapy: A Case Report. Reports, 8(3), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030158