Blue Nevi and Melanoma Arising in Blue Nevus: A Comparative Histopathological Case Series

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

2. Case Presentation

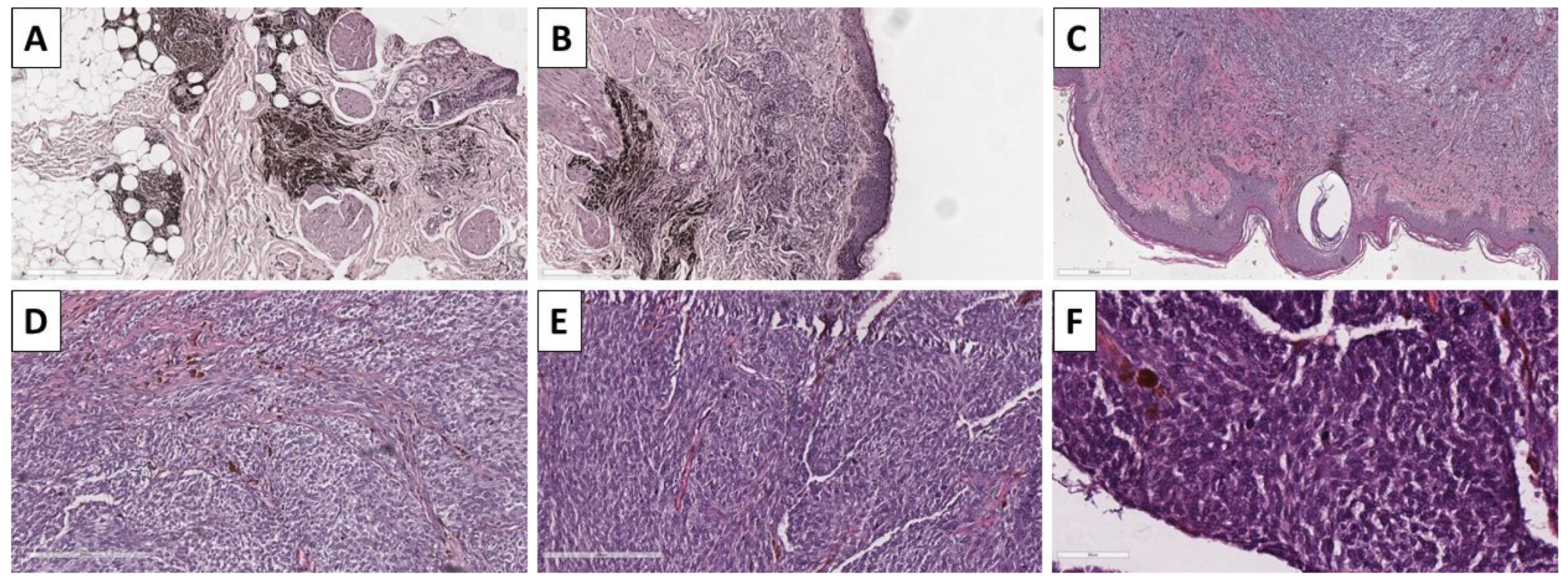

2.1. Cases 1 and 2—Conventional Dendritic Blue Nevus and Sclerotic Dendritic Blue Nevus

2.2. Case 3—Conventional Cellular Blue Nevus

2.3. Case 4—Cellular Blue Nevus as a Secondary Finding in a Patient with In Situ Clear Cell Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Superficial Spreading Melanoma

2.4. Case 5—Melanoma Arising in Blue Nevus

3. Discussion

Future Directions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scott, D.W.; Miller, W.H. Neoplastic and Non-Neoplastic Tumors. In Equine Dermatology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 698–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.W.; Miller, W.H. Diagnostic Methods. In Equine Dermatology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 59–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, J.R.; Assaf, C.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Tebbe, B. Bilateral Naevus of Ota: A Rare Manifestation in a Caucasian. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2004, 18, 353–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschini, D.; Dinulos, J.G. Dermal Melanocytosis and Associated Disorders. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2015, 27, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.; Thappa, D.M. Mongolian Spots–A Prospective Study. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2013, 30, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, J.Y.; Walls, B.E.; Pomerantz, H.; Yoon, C.H.; Buchbinder, E.I.; Werchniak, A.E.; Dong, F.; Lian, C.G.; Granter, S.R. Melanoma Arising in a Nevus of Ito: Novel Genetic Mutations and a Review of the Literature on Cutaneous Malignant Transformation of Dermal Melanocytosis. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2016, 43, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, N.M.; Gurnani, P.; Labib, A.; Nuesi, R.; Nouri, K. Melanoma in the Setting of Nevus of Ota: A Review for Dermatologists. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, C.; Wiedemeyer, K.; Mehta, A.; Rojas-Garcia, P.; Temple-Oberle, C.; Orlando, A.; Miller, K.; Gharpuray-Pandit, D.; Brenn, T. The Clinico-Pathological Spectrum of Plaque-Type Blue Naevi and Their Potential for Malignant Transformation. Histopathology 2024, 84, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembowicz, A. Blue Nevi and Related Tumors. Clin. Lab. Med. 2017, 37, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalirai, H.; Dodson, A.; Faqir, S.; Damato, B.E.; Coupland, S.E. Lack of BAP1 Protein Expression in Uveal Melanoma Is Associated with Increased Metastatic Risk and Has Utility in Routine Prognostic Testing. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 1373–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesner, T.; Obenauf, A.C.; Murali, R.; Fried, I.; Griewank, K.G.; Ulz, P.; Windpassinger, C.; Wackernagel, W.; Loy, S.; Wolf, I.; et al. Germline Mutations in BAP1 Predispose to Melanocytic Tumors. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 1018–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.L.; Neishaboori, N.; Tetzlaff, M.T.; Chen, W.S.; Aung, P.P.; Curry, J.L.; Nagarajan, P.; Ivan, D.; Hwu, W.J.; Prieto, V.G.; et al. BAP-1 Expression Status by Immunohistochemistry in Cellular Blue Nevus and Blue Nevus-like Melanoma. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2020, 42, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griewank, K.G.; Müller, H.; Jackett, L.A.; Emberger, M.; Möller, I.; Van De Nes, J.A.P.; Zimmer, L.; Livingstone, E.; Wiesner, T.; Scholz, S.L.; et al. SF3B1 and BAP1 Mutations in Blue Nevus-like Melanoma. Mod. Pathol. 2017, 30, 928–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohman, M.E.; Steen, A.J.; Grekin, R.C.; North, J.P. The utility of PRAME staining in identifying malignant transformation of melanocytic nevi. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2021, 48, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lezcano, C.; Pulitzer, M.; Moy, A.P.; Hollmann, T.J.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Busam, K.J. Immunohistochemistry for PRAME in the Distinction of Nodal Nevi from Metastatic Melanoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020, 44, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, S.H.C.; Finkelman, B.S.; Yeldandi, A.V. The diagnostic utility of PRAME and p16 in distinguishing nodal nevi from nodal metastatic melanoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2020, 216, 153105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavan, S.S.; Wang, J.Y.; Kwok, S.; Rieger, K.E.; Novoa, R.A.; Brown, R.A. PRAME expression in melanocytic proliferations with intermediate histopathologic or spitzoid features. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2020, 47, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezcano, C.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Busam, K.J. PRAME Immunohistochemistry as an Ancillary Test for the Assessment of Melanocytic Lesions. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2021, 14, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, A.K.; Tharp, A.W.; Umphress, B.; Kowal, R.P. The utility of PRAME immunohistochemistry in the evaluation of challenging melanocytic tumors. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2021, 48, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezcano, C.; Müller, A.M.; Frosina, D.; Hernandez, E.; Geronimo, J.A.; Busam, K.J.; Jungbluth, A.A. Immunohistochemical Detection of Cancer-Testis Antigen PRAME. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2021, 29, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowski, M.; Chłopek, M.; Kruczak, A.; Ryś, J.; Lasota, J.; Miettinen, M. PRAME Expression in Cancer. A Systematic Immunohistochemical Study of >5800 Epithelial and Nonepithelial Tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2022, 46, 1467–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fouchardière, A.; Caillot, C.; Jacquemus, J.; Durieux, E.; Houlier, A.; Haddad, V.; Pissaloux, D. β-Catenin nuclear expression discriminates deep penetrating nevi from other cutaneous melanocytic tumors. Virchows Arch. 2019, 474, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Raamsdonk, C.D.; Griewank, K.G.; Crosby, M.B.; Garrido, M.C.; Vemula, S.; Wiesner, T.; Obenauf, A.C.; Wackernagel, W.; Green, G.; Bouvier, N.; et al. Mutations in GNA11 in Uveal Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2191–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, I.; Gamsizkan, M.; Sari, S.O.; Yaman, B.; Demirkesen, C.; Heper, A.; Calli, A.O.; Narli, G.; Kucukodaci, Z.; Berber, U.; et al. Molecular Alterations in Malignant Blue Nevi and Related Blue Lesions. Virchows Arch. 2015, 467, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, V.Y.; Russell-Goldman, E.; Yoon, C.H.; Doyle, L.A.; Hanna, J. Melanoma Arising in Extracutaneous Cellular Blue Naevus: Report of Two Cases with Comparison to Cutaneous Counterparts and Uveal Melanoma. Histopathology 2022, 81, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Byrne, M.; Pissaloux, D.; Haddad, V.; Paindavoine, S.; Thomas, L.; Aubin, F.; Lesimple, T.; Grange, F.; Bonniaud, B.; et al. Melanomas Associated with Blue Nevi or Mimicking Cellular Blue Nevi: Clinical, Pathologic, and Molecular Study of 11 Cases Displaying a High Frequency of GNA11 Mutations, BAP1 Expression Loss, and a Predilection for the Scalp. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antibody | Expression in Nevi | Expression in Blue Nevi | Expression in Melanoma | Expression in Melanoma Arising in Blue Nevus | Expression in Other Tumors Mimicking Melanocytic Neoplasia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOX10 | + | + | + * | + * | + |

| S100 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Melan-A | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− | + |

| HBM-45 | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− | + |

| BRAF V600E | +/− | +/− | +/− | - | + |

| BAP1 | + | + | +/− | +/− | + |

| PRAME | +/− | No data | +/− | No data | + |

| Differentiatial Diagnosis | Cellular Blue Nevus | Other Melanoma Types | Melanoma Recurrence or Cutaneous Metastasis | Clear Cell Sarcoma | Other Rare Melanocytic Lesions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma arising in blue nevus |

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popov, H.; Pavlov, P.; Stoyanov, G.S. Blue Nevi and Melanoma Arising in Blue Nevus: A Comparative Histopathological Case Series. Reports 2025, 8, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030131

Popov H, Pavlov P, Stoyanov GS. Blue Nevi and Melanoma Arising in Blue Nevus: A Comparative Histopathological Case Series. Reports. 2025; 8(3):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030131

Chicago/Turabian StylePopov, Hristo, Pavel Pavlov, and George S. Stoyanov. 2025. "Blue Nevi and Melanoma Arising in Blue Nevus: A Comparative Histopathological Case Series" Reports 8, no. 3: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030131

APA StylePopov, H., Pavlov, P., & Stoyanov, G. S. (2025). Blue Nevi and Melanoma Arising in Blue Nevus: A Comparative Histopathological Case Series. Reports, 8(3), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030131