Giant Atypical Neurofibroma of the Calf in Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction and Clinical Significance

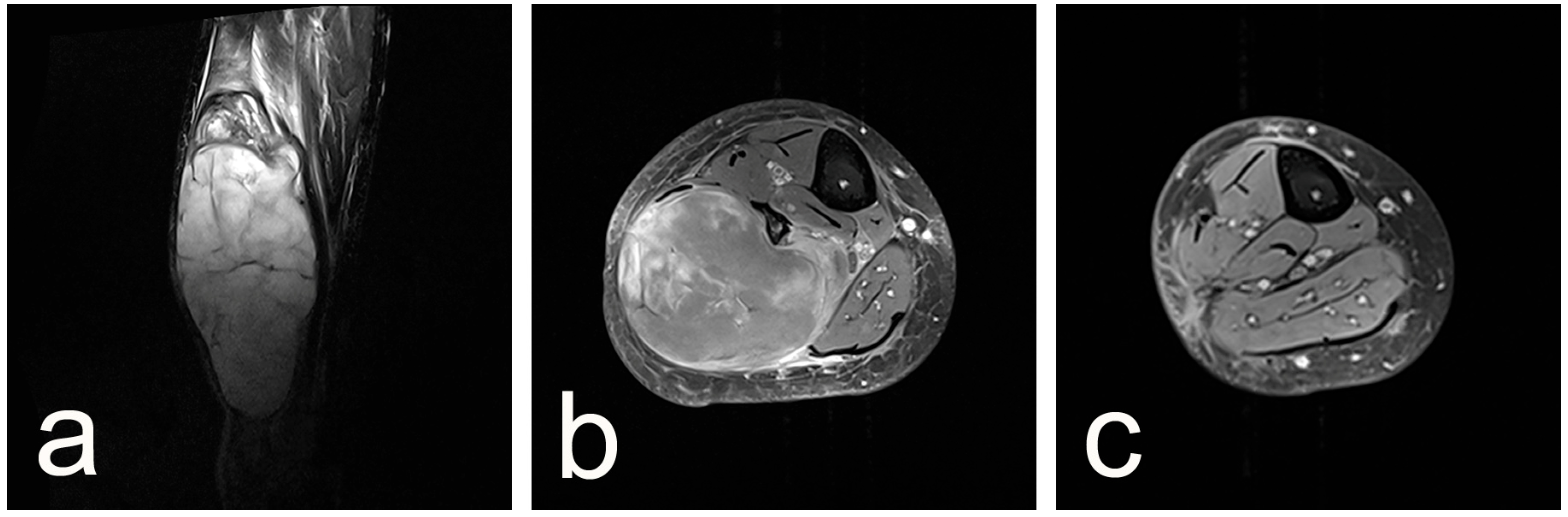

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NF1 | Neurofibromatosis Type 1 |

| PNST | Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor |

| MPNST | Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor |

| ANNUBP | Atypical Neurofibromatous Neoplasm of Uncertain Biologic Potential |

| AN | Atypical Neurofibroma |

| CDKN2A/B | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2A and 2B |

| S100 | S100 protein (marker for neural/melanocytic cells) |

| CD34 | Cluster of Differentiation 34 (marker for vascular/endothelial and fibroblastic cells) |

| Ki-67 | Marker of cellular proliferation |

| p53 | Tumor protein p53 (tumor suppressor) |

| SMA/α-SMA | (Alpha-) Smooth Muscle Actin |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| HPF | High-Power Field (in microscopy) |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| FDG | Fluorodeoxyglucose (used in PET imaging) |

| LG-MPNST | Low-Grade Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Joshi, M.R. Honokiol: Treatment for Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2023, 19, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adil, A.; Koritala, T.; Munakomi, S.; Singh, A.K. Neurofibromatosis Type 1; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459358/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Hirbe, A.C.; Gutmann, D.H. Neurofibromatosis Type 1: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Care. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somatilaka, B.N.; Sadek, A.; McKay, R.M.; Le, L.Q. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor: Models, Biology, and Translation. Oncogene 2022, 41, 2405–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, A.M.; Wolters, P.L.; Dombi, E.; Baldwin, A.; Whitcomb, P.; Fisher, M.J.; Weiss, B.; Kim, A.; Bornhorst, M.; Shah, A.C.; et al. Selumetinib in Children with Inoperable Plexiform Neurofibromas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1430–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariel, I.M. Tumors of the Peripheral Nervous System. CA Cancer J. Clin. 1983, 33, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernthal, N.M.; Jones, K.B.; Monument, M.J.; Liu, T.; Viskochil, D.; Randall, R.L. Lost in Translation: Ambiguity in Nerve Sheath Tumor Nomenclature and Its Resultant Treatment Effect. Cancers 2013, 5, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miettinen, M.M.; Antonescu, C.R.; Fletcher, C.D.M.; Kim, A.; Lazar, A.J.; Quezado, M.M.; Reilly, K.M.; Stemmer-Rachamimov, A.; Stewart, D.R.; Viskochilet, D.; et al. Histopathologic Evaluation of Atypical Neurofibromatous Tumors and Their Transformation into Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor in Patients with Neurofibromatosis 1—A Consensus Overview. Hum. Pathol. 2017, 67, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higham, C.S.; Dombi, E.; Rogiers, A.; Bhaumik, S.; Pans, S.; Connor, S.E.J.; Miettinen, M.; Sciot, R.; Tirabosco, R.; Brems, H.; et al. The Characteristics of 76 Atypical Neurofibromas as Precursors to Neurofibromatosis 1 Associated Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors. Neuro-Oncology 2018, 20, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich, R.E.; Noernberg, L.K.; Hagel, C. Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors in Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Morphological and Immunohistochemical Study. Anticancer Res. 2022, 42, 1247–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambarotti, M. Malignant Schwannoma: Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor. In Atlas of Musculoskeletal Tumors and Tumorlike Lesions: The Rizzoli Case Archive; Picci, P., Manfrini, M., Fabbri, N., Gambarotti, M., Vanel, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 341–344. [Google Scholar]

- Beert, E.; Brems, H.; Daniëls, B.; De Wever, I.; Van Calenbergh, F.; Schoenaers, J.; Debiec-Rychter, M.; Gevaert, O.; De Raedt, T.; Van Den Bruel, A.; et al. Atypical Neurofibromas in Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Are Premalignant Tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2011, 50, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernthal, N.M.; Putnam, A.; Jones, K.B.; Viskochil, D.; Randall, R.L. The Effect of Surgical Margins on Outcomes for Low Grade MPNSTs and Atypical Neurofibroma. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 110, 813–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, A.; Reuss, D.; Rodriguez, F. Neurofibroma. In Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours, 5th ed.; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, Ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020; Volume 3, pp. 232–236. Available online: https://publications.iarc.fr/588 (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Grübel, N.; Antoniadis, G.; König, R.; Wirtz, C.R.; Bremer, J.; Pala, A.; Reuter, M.; Pedro, M.T. Case Report: Atypical Neurofibromatous Neoplasm with Uncertain Biological Potential of the Sciatic Nerve and a Widespread Arteriovenous Fistula Mimicking a Malignant Peripheral Nerve Tumor in a Young Patient with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1391456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, J.P.M.; Neves, M.W.F.; Marchi, C.; Nakasone, F.J.; Maldaun, M.V.C.; Aguiar, P.H.P.; de Aguiar, P.H.P.; Scappini, W., Jr. Giant Dumbbell C2C3 Neurofibroma Invading Prebulbar Cistern: Case Report and Literature Review. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2019, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Lu, H. A Solitary Giant Neurofibroma of Inguinal Region: A Case Report. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 00368504211004269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Pokhrel, B.; Khadka, N.; Rayamajhi, S.; Man Shrestha, J.; Lohani, I. A 63-kg Giant Neurofibroma in the Right Lower Extremity and Gluteal Region of a 22-Year-Old Woman: A Case Report. Clin. Case Rep. 2021, 9, e04152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vélez, R.; Barrera-Ochoa, S.; Barastegui, D.; Pérez-Lafuente, M.; Romagosa, C.; Pérez, M. Multidisciplinary Management of a Giant Plexiform Neurofibroma by Double Sequential Preoperative Embolization and Surgical Resection. Case Rep. Neurol. Med. 2013, 2013, 987623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, K.; Gaydarski, L.; Panev, A.; Landzhov, B.; Tubbs, R.S.; Georgiev, G.P. A Rare Case of Sural Schwannoma with Involvement of the Medial Sural Cutaneous Nerve: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e66190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, A.W.; Shurell, E.; Singh, A.; Dry, S.M.; Eilber, F.C. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 25, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kransdorf, M.J.; Bancroft, L.W.; Peterson, J.J.; Murphey, M.D.; Foster, W.C.; Temple, H.T. Imaging of Fatty Tumors: Distinction of Lipoma and Well-Differentiated Liposarcoma. Radiology 2002, 224, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, C.B.; St Hilaire, N.J. Epidermal Inclusion Cyst; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532310/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Trinidad, C.M.; Wangsiricharoen, S.; Prieto, V.G.; Aung, P.P. Rare Variants of Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans: Clinical, Histologic, and Molecular Features and Diagnostic Pitfalls. Dermatopathology 2023, 10, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, A. Endobronchial Neurogenic Tumor: A Combination of Traumatic Neuroma and Neurofibroma. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2017, 20, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasper, B.; Ströbel, P.; Hohenberger, P. Desmoid Tumors: Clinical Features and Treatment Options for Advanced Disease. Oncologist 2011, 16, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Klonowski, P.W.; Lind, A.C.; Lu, D. Differentiating Neurotized Melanocytic Nevi from Neurofibromas Using Melan-A (MART-1) Immunohistochemical Stain. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2012, 136, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, B.J.; Laudadio, J. Aggressive Angiomyxoma. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2012, 136, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anil, G.; Tan, T.Y. CT and MRI Evaluation of Nerve Sheath Tumors of the Cervical Vagus Nerve. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 197, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldatos, T.; Fisher, S.; Karri, S.; Ramzi, A.; Sharma, R.; Chhabra, A. Advanced MR Imaging of Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors Including Diffusion Imaging. Semin. Musculoskelet. Radiol. 2015, 19, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristow, I.; Kaul, M.G.; Stark, M.; Zapf, A.; Riedel, C.; Lenz, A.; Mautner, V.F.; Farschtschi, S.; Apostolova, I.; Adam, G.; et al. Discrimination of Benign, Atypical, and Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors in Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Using Diffusion-Weighted MRI. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2024, 6, vdae021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messersmith, L.; Krauland, K. Neurofibroma; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539707/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Park, J.Y.; Park, H.; Park, N.J.; Park, J.S.; Sung, H.J.; Lee, S.S. Use of Calretinin, CD56, and CD34 for Differential Diagnosis of Schwannoma and Neurofibroma. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2011, 45, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.X.; Dillman, J.R.; Guccione, J.; Habiba, A.; Maher, M.; Kamel, S.; Panse, P.M.; Jensen, C.T.; Elsayes, K.M. Neurofibromatosis from Head to Toe: What the Radiologist Needs to Know. Radiographics 2022, 42, 1123–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charifa, A.; Azmat, C.E.; Badri, T. Lipoma Pathology; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482343/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Trinh, C.T.; Nguyen, C.H.; Chansomphou, V.; Chansomphou, V.; Tran, T.T.T. Overview of Epidermoid Cyst. Eur. J. Radiol. Open 2019, 6, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neelon, D.; Lannan, F.; Childs, J. Granular Cell Tumor; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563150/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Baheti, A.D.; Tirumani, S.H.; Rosenthal, M.H.; Howard, S.A.; Shinagare, A.B.; Ramaiya, N.H.; Jagannathan, J.P. Myxoid Soft-Tissue Neoplasms: Comprehensive Update of the Taxonomy and MRI Features. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015, 204, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, K.M.; Kim, A.; Blakely, J.; Ferner, R.E.; Gutmann, D.H.; Legius, E.; Miettinen, M.M.; Randall, R.L.; Ratner, N.; Jumbé, N.L.; et al. Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Associated MPNST State of the Science: Outlining a Research Agenda for the Future. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djx124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tumor | Clinical Features | Histological Appearance | Immunohistochemical Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurofibroma | Rubbery, often painless cutaneous or subcutaneous nodules; may cause itching, tenderness, or disfigurement (plexiform type); neurological deficits if deep or spinal involvement [2] | Mixed cellularity (Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineural cells, mast cells) in myxoid stroma; wavy nuclei, “shredded-carrot” collagen [32] | S100 positivity in ~50% of cells; CD34-positive spindle fibroblasts (“fingerprint” pattern); occasional EMA in perineural cells; neurofilament in intratumoral axons [32] |

| Schwannoma | Solitary or multiple, can be asymptomatic or cause pain/numbness/tingling; vestibular schwannoma → hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo [20,30] | Encapsulated proliferation of Schwann cells with Antoni A (Verocay bodies) and Antoni B areas; absence of intralesional axons [20,32] | Diffuse, strong S100 positivity; calretinin+; CD56+; CD34 negative [32,33] |

| MPNST | Rapidly enlarging painful mass, often in NF1 patients; new neurological deficits; systemic symptoms rare [21,31] | Hypercellular spindle cells in herringbone/fasciculated patterns, pleomorphism, high mitotic rate, necrosis [21,32] | Variable S100 (50–70%, often decreased in high-grade); p53+ in ~75%; EGFR+ in ~35%; loss of H3K27me3 [21,32] |

| Lipoma | Soft, doughy, mobile subcutaneous mass; usually asymptomatic unless compressive [34,35] | Mature adipocytes with thin fibrous septa; often encapsulated [35] | Typically vimentin+; no diagnostic S100 or CD34 staining pattern described |

| Epidermal Inclusion Cyst | Firm, freely movable nodules with central punctum; may become inflamed/infected, painful, discharge keratinous material [23] | Cyst lined by stratified squamous epithelium with granular layer; lumen filled with laminated keratin [23] | Not routinely characterized by IHC [23] |

| DFSP | Indurated, slowly growing dermal plaque or nodule, often on trunk or proximal limbs; may mimic a bruise [24] | Uniform spindle cells in storiform (cartwheel) pattern; honeycomb infiltration of subcutis [24] | Strong CD34+; vimentin+; S100–, factor XIIIa– [24] |

| Traumatic Neuroma | Painful/tender firm nodule at site of prior nerve injury or surgery [25] | Disorganized bundles of nerve fascicles (axons), Schwann cells and fibroblasts within collagenous scar [25] | S100+ in Schwann cells [25] |

| Granular Cell Tumor | Solitary, painless, slow-growing nodules (commonly tongue, head/neck); may be multiple in syndromes [36,37] | Large polygonal cells with small nuclei, abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm; Pustulo-ovoid bodies of Milian; pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of overlying epidermis [37] | Strong S100+; vimentin+; CD68 variably+; PAS-positive granules (diastase resistant) [37] |

| Desmoid Tumor | Firm, sometimes painful mass in abdomen or extremities; associated with FAP or prior surgery/pregnancy [26] | Bland fibroblasts/myofibroblasts in sweeping fascicles; infiltrative borders; low mitoses [26] | Nuclear β-catenin+; vimentin+; SMA variably+; S100– [26] |

| Dermal Neurotized Melanocytic Nevus | Pigmented dermal papule or nodule; may mimic neurofibroma clinically [27] | Neurotized nevus cells in dermis; may have increased mast cells [27] | Melan-A/MART-1 strong+ in nevus cells; S100+; neurofibromas are Melan-A [27] |

| Aggressive Angiomyxoma | Deep perineal/pelvic mass in women of child-bearing age; often asymptomatic viscerally [28,38,39] | Low cellularity spindle cells in myxoid stroma with numerous blood vessels; infiltrative edges [28] | Estrogen and progesterone receptor+; vimentin+; desmin variably+ [28] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaydarski, L.; Georgiev, G.P.; Slavchev, S.A. Giant Atypical Neurofibroma of the Calf in Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Case Report and Literature Review. Reports 2025, 8, 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030112

Gaydarski L, Georgiev GP, Slavchev SA. Giant Atypical Neurofibroma of the Calf in Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Case Report and Literature Review. Reports. 2025; 8(3):112. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030112

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaydarski, Lyubomir, Georgi P. Georgiev, and Svetoslav A. Slavchev. 2025. "Giant Atypical Neurofibroma of the Calf in Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Case Report and Literature Review" Reports 8, no. 3: 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030112

APA StyleGaydarski, L., Georgiev, G. P., & Slavchev, S. A. (2025). Giant Atypical Neurofibroma of the Calf in Neurofibromatosis Type 1: Case Report and Literature Review. Reports, 8(3), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports8030112