Stability Analysis for an Ultra-Lightweight Glider Airplane with Electric Driven Two-Blade Propeller

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Wind turbines,

- The ramair turbine in commercial aircraft as an emergency power supply,

- Helicopters,

- Sports aircraft.

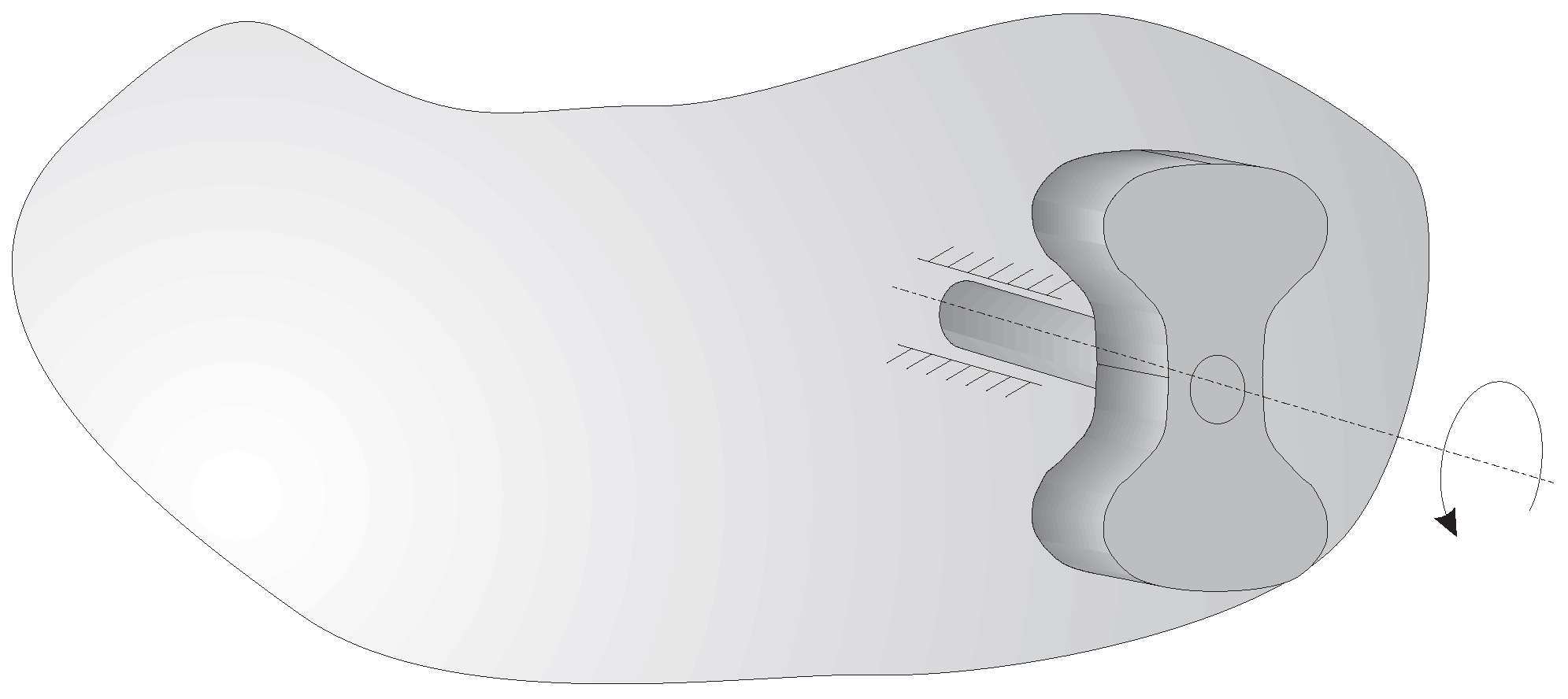

2. The Glider Test Object

2.1. Glider Design

2.2. Basic Modal Analysis

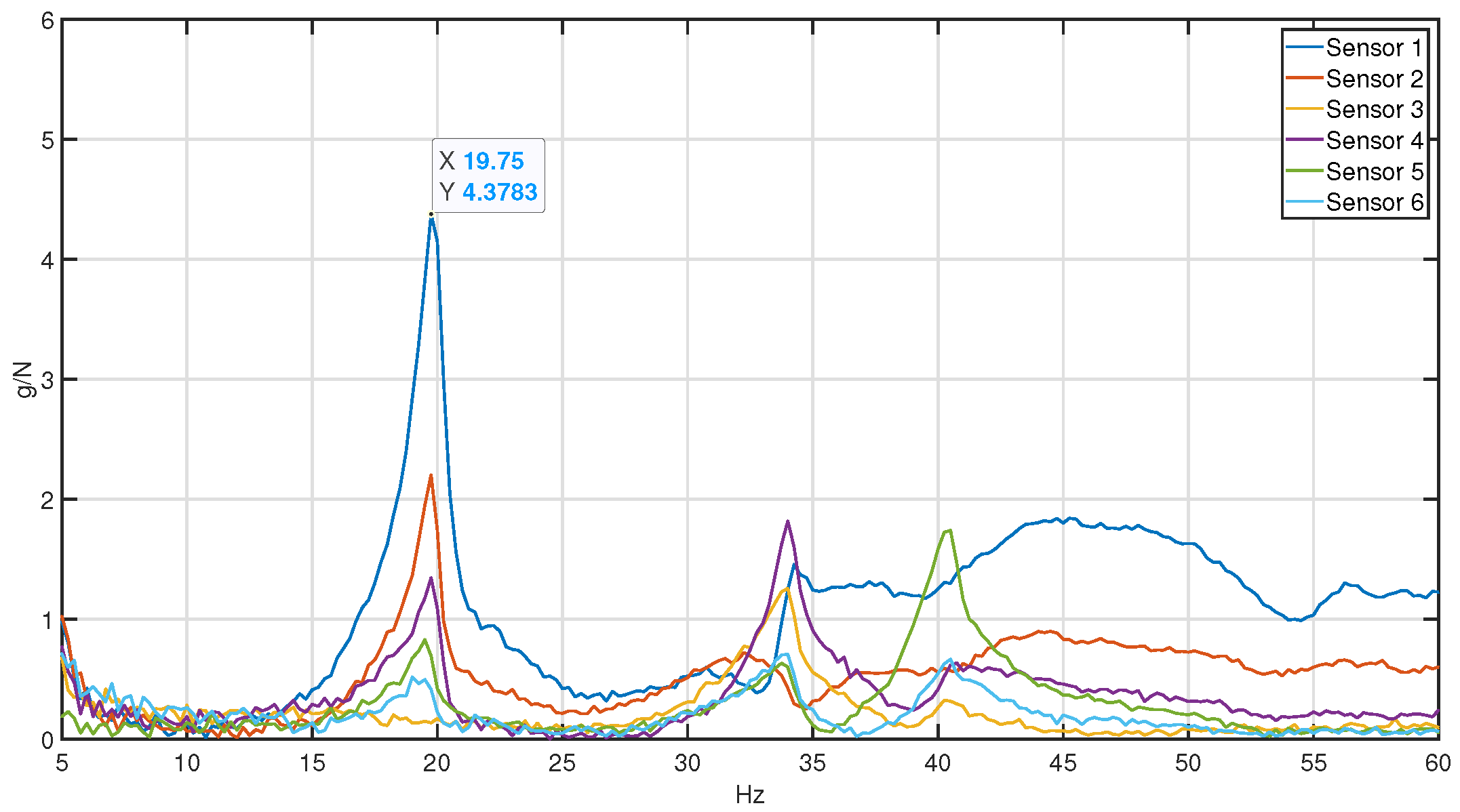

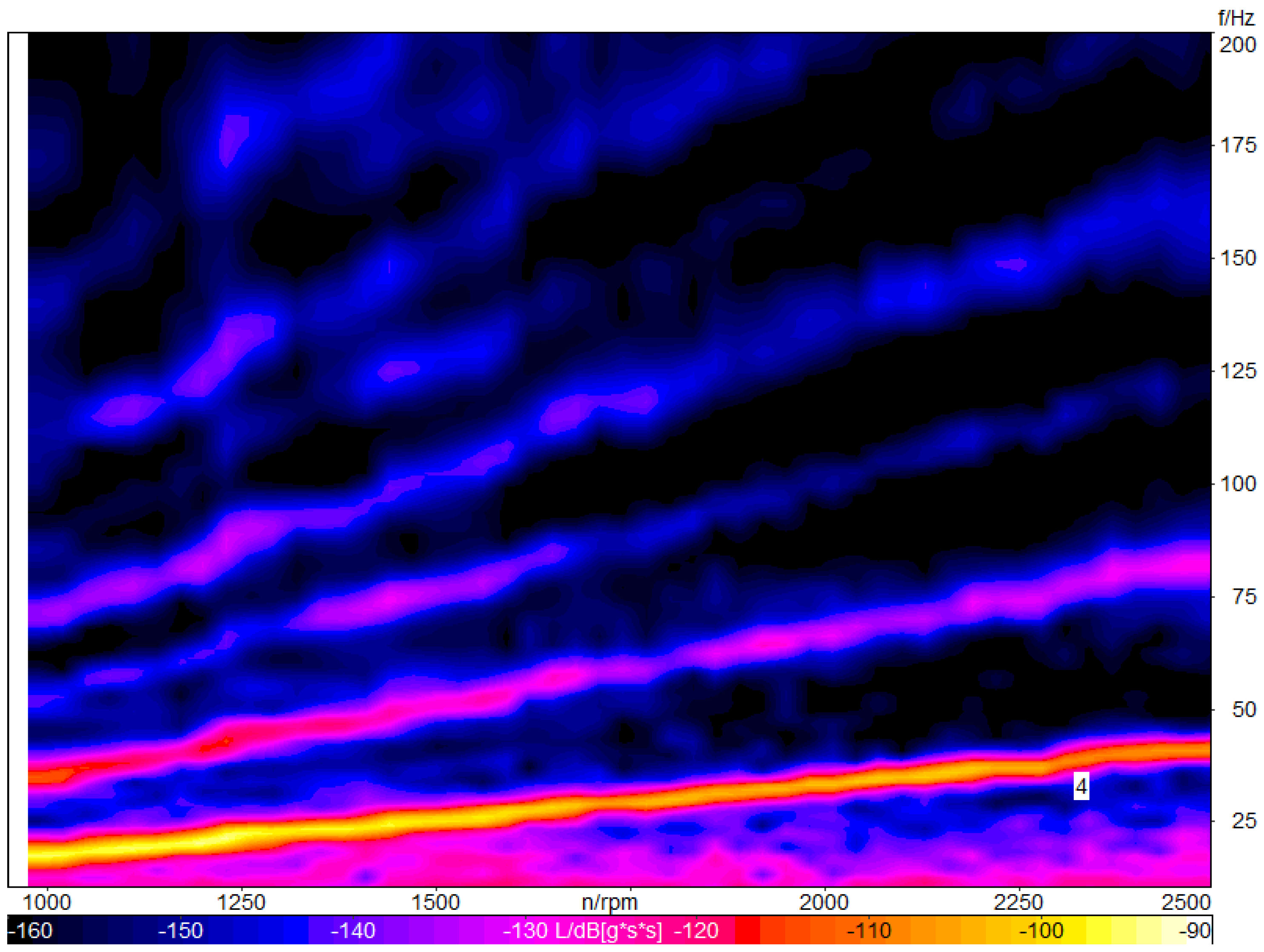

2.3. Test in Operation

3. Introduction of Time-Varying Effects in Structure Dynamics

3.1. Equation of Motion of the Rotor

3.2. The Equation of Motion of the Overall Structure

4. Theoretical Modal Analysis

4.1. State Space Formulation

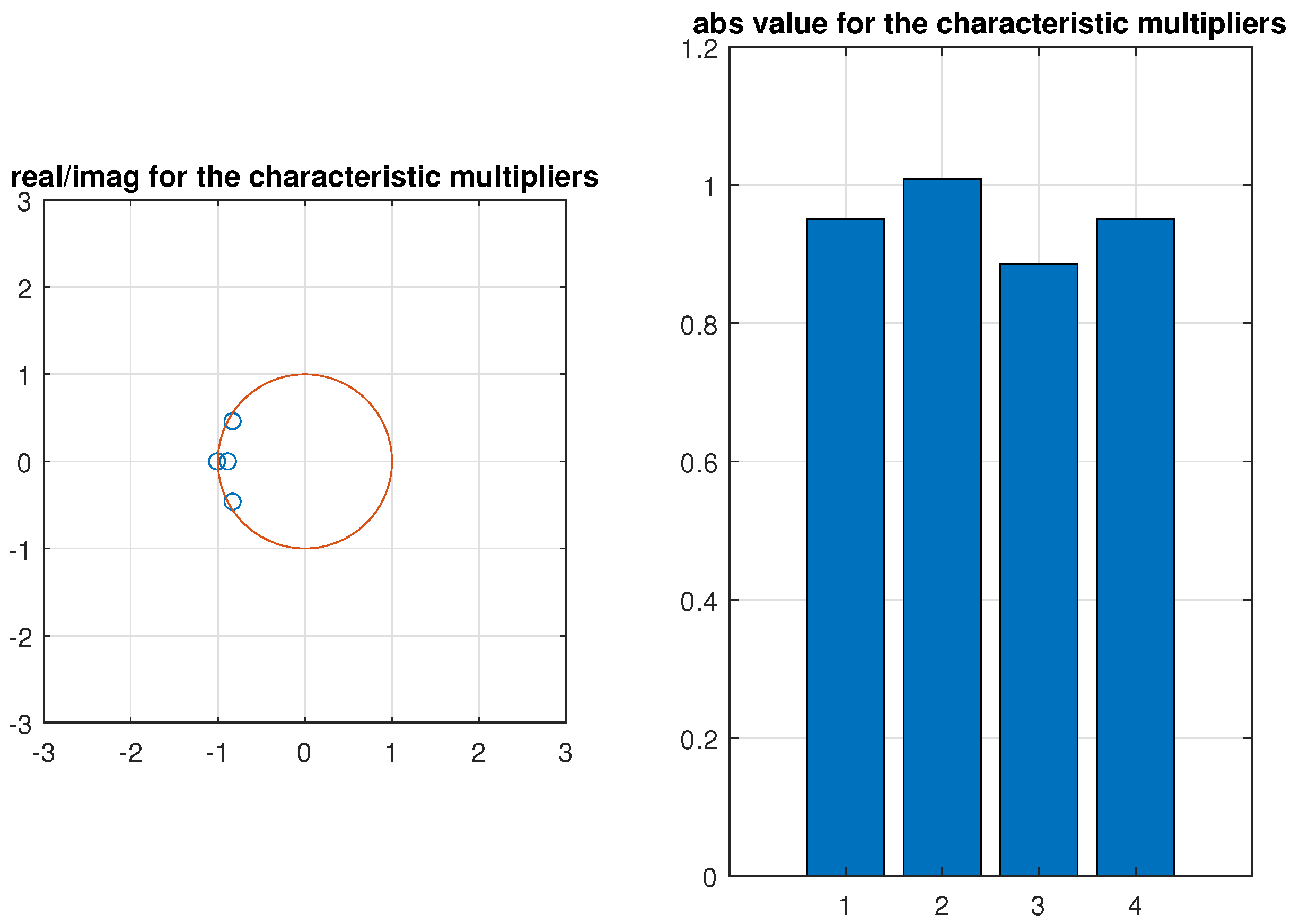

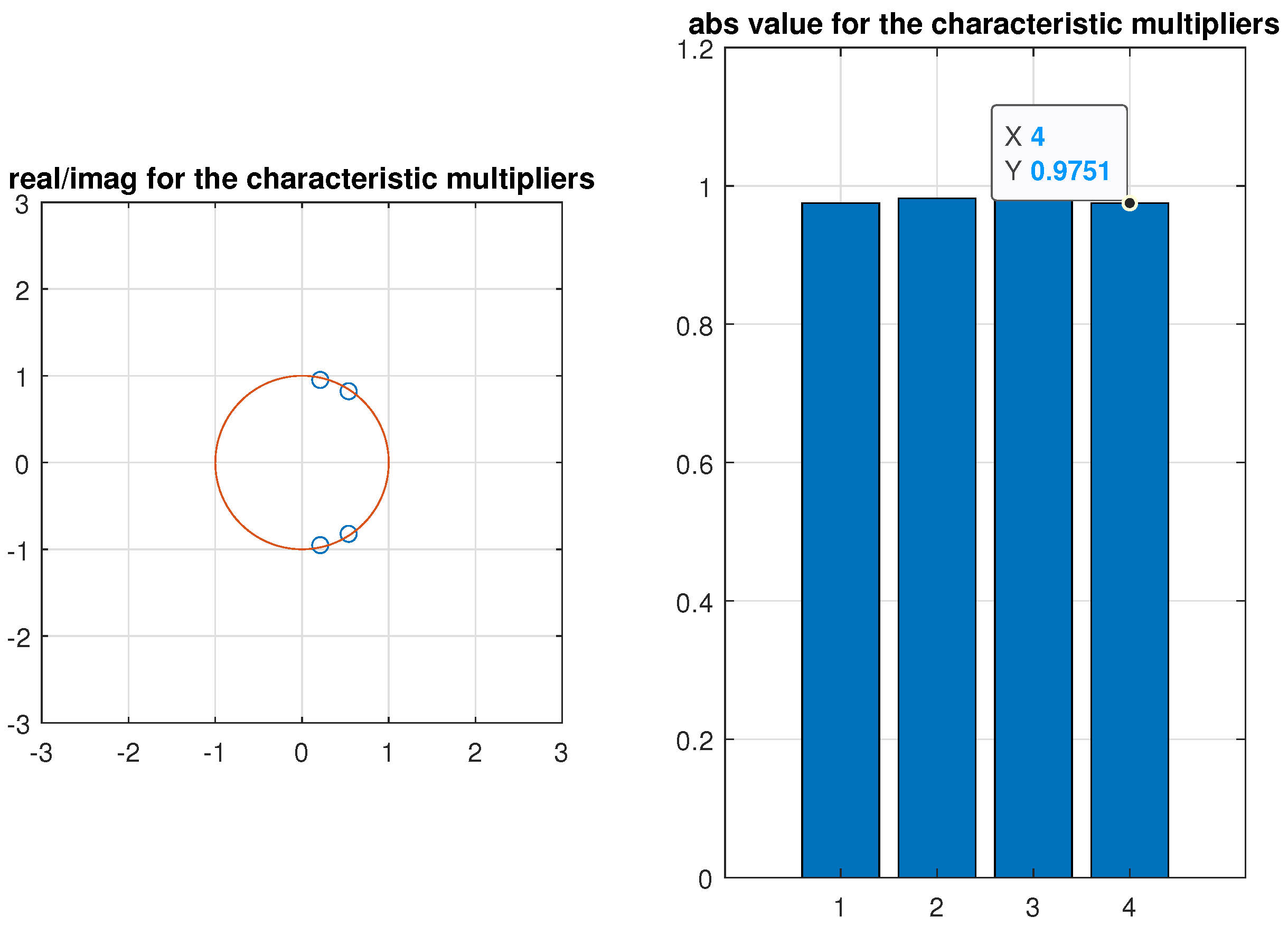

4.2. Floquet Stability

- Unstable for for at least one eigenvalue,

- Marginally stable for for one and for all other eigenvalues,

- Asymptotically stable for for all eigenvalues.

- leads to periodic solutions of period , and

- leads to periodic solutions of period ,

4.3. Hill’s Hyper-Eigenvalue Problem

- Unstable for for at least one characteristic exponent,

- Marginally stable for for at least one characteristic exponent and for all others ,

- Stable for for all characteristic exponents.

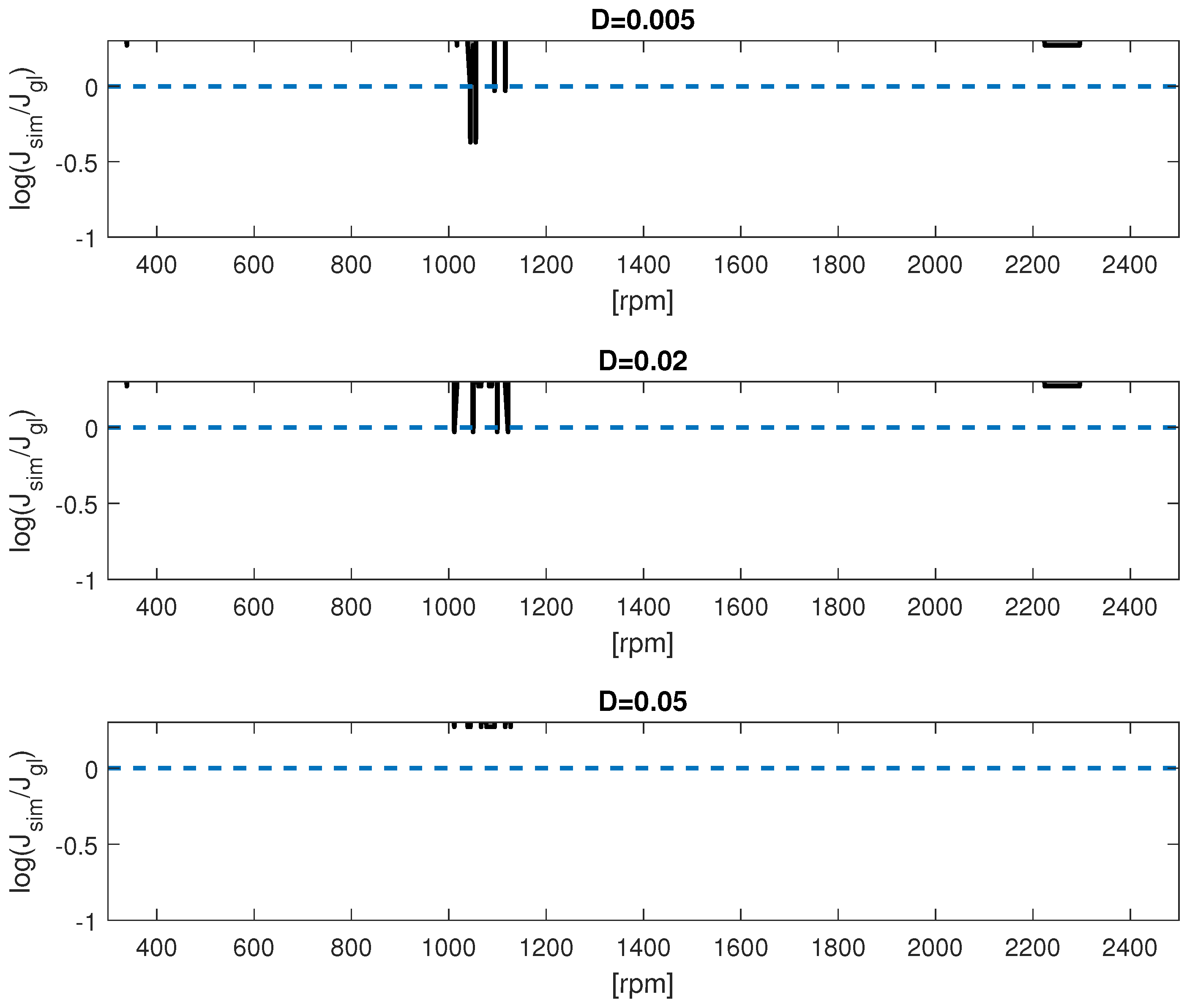

5. Simulation Results for the Glider

- Damping in different subplots; the damping is varied from the real structure to an upper and lower extreme (: lower extreme for a airplane body with fitted metal materials; : glider under investigation; : glider with extra damping treatments).

- , where is a scaling factor to the effective of the glider in Equations (6) and (7); this varies the parameter amplitude in the simulation; for a better spread in the diagram the is taken, so that the effective corresponds to ; steps are as the sensitivity to the change of parameter amplitude is low ( in the glider).

- Rotor speed in the relevant range of the glider from 300 to 2500 in 400 simulation steps; this covers the complete rpm range during the operation of the glider.

- To avoid inaccuracy in the Fourier series of the eigenvectors, the time-constant block Equation in (30) should be in the centre according . Then, the Fourier components between are balanced. The constant block is expected to have the largest vector length, so that this is a criterion for the selection.

- The imaginary part of the hyper-eigenvalue is expected to be close to the imaginary part of the system without parametric excitation but with consideration of the rotational speed . So, the vicinity of the two assigned eigenvalues are the criterion for selection.

- The structural Damping D.

- The unsymmetry of the rotor in terms of .

- The rotor speed in the relevant range of operation.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DOF | Degrees of freedom |

| EVP | Eigenvalue problem |

| FRF | Frequency response function |

| ODE | Ordinary differential equation |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

Appendix B

References

- Floquet, G. Sur les équations différentielles linéaires à coefficients périodiques. Ann. Sci. l’École Norm. Supér. 1883, 12, 47–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.W. On the part of the motion of the lunar perigee which is a function of the mean motions of the sun and moon. Acta Math. 1886, 8, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondl, A. Effect of the non-linear parametric excitation. Acta Tech. CSAV (Ceskoslovensk Akad. Ved) 1985, 30, 640–649. [Google Scholar]

- Dohnal, F. Damping of Mechanical Vibrations by Parametric Excitation. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ecker, H. Beneficial Effects of Parametric Excitation in Rotor Systems. In Proceedings of the IUTAM Symposium on Emerging Trends in Rotor Dynamics, New Delhi, India, 23—26 March 2009; Gupta, K., Ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 361–371. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, Z.; Karev, A.; Hagedorn, P.; Dohnal, F. Enhancing vibration mitigation in a Jeffcott rotor with active magnetic bearings through parametric excitation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2022, 109, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasem, G.T.; Gastaldi, C.; Berruti, T.M. Trained Harmonic Balance Method for Parametrically Excited Jeffcott Rotor Analysis. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 16, 011003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, T.Ø.H.; Santos, I.F. Experimental & operational modal analysis applied to rotor-blade systems in a fully controlled testing environment. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2021, 43, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, T.; Harata, Y.; Miyazawa, Y.; Ishida, Y. Parametric resonances of floating wind turbines blades under vertical wave excitation. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 211, 18004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tcherniak, D. Rotor anisotropy as a blade damage indicator for wind turbine structural health monitoring systems. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2016, 74, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, T.; Harata, Y.; Ishida, Y. Unstable vibrations of a wind turbine tower with two blades. In Proceedings of the ASME 2012 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 12–15 August 2012; Volume 1, pp. 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnet, S. Schwingungsanalysen an Einem Segelflugzeug Mit Elektrischem Hilfsantrieb Mittels Simulation und Versuch. Bachelor’s Thesis, Technische Hochschule Ingolstadt, Ingolstadt, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bienert, J. Strukturmodifikation in der Modalanalyse am Beispiel der Kreiselwirkung von Rotoren, als ms. gedr ed.; Fortschrittberichte VDI: Reihe 11, Schwingungstechnik; VDI-Verl.: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1998; Volume 255. [Google Scholar]

- Iakubovich, V.A.; Starzhinskii, V.M. Linear Differntial Equations with Periodic Coefficients; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bienert, J.; Regnet, S. Stability Analysis for an Ultra-Lightweight Glider Airplane with Electric Driven Two-Blade Propeller. Vibration 2026, 9, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration9010003

Bienert J, Regnet S. Stability Analysis for an Ultra-Lightweight Glider Airplane with Electric Driven Two-Blade Propeller. Vibration. 2026; 9(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration9010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleBienert, Joerg, and Simon Regnet. 2026. "Stability Analysis for an Ultra-Lightweight Glider Airplane with Electric Driven Two-Blade Propeller" Vibration 9, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration9010003

APA StyleBienert, J., & Regnet, S. (2026). Stability Analysis for an Ultra-Lightweight Glider Airplane with Electric Driven Two-Blade Propeller. Vibration, 9(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration9010003