Current-Carrying Performance Degradation Mechanisms of Outdoors Power Connectors Under External Vibrations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Details

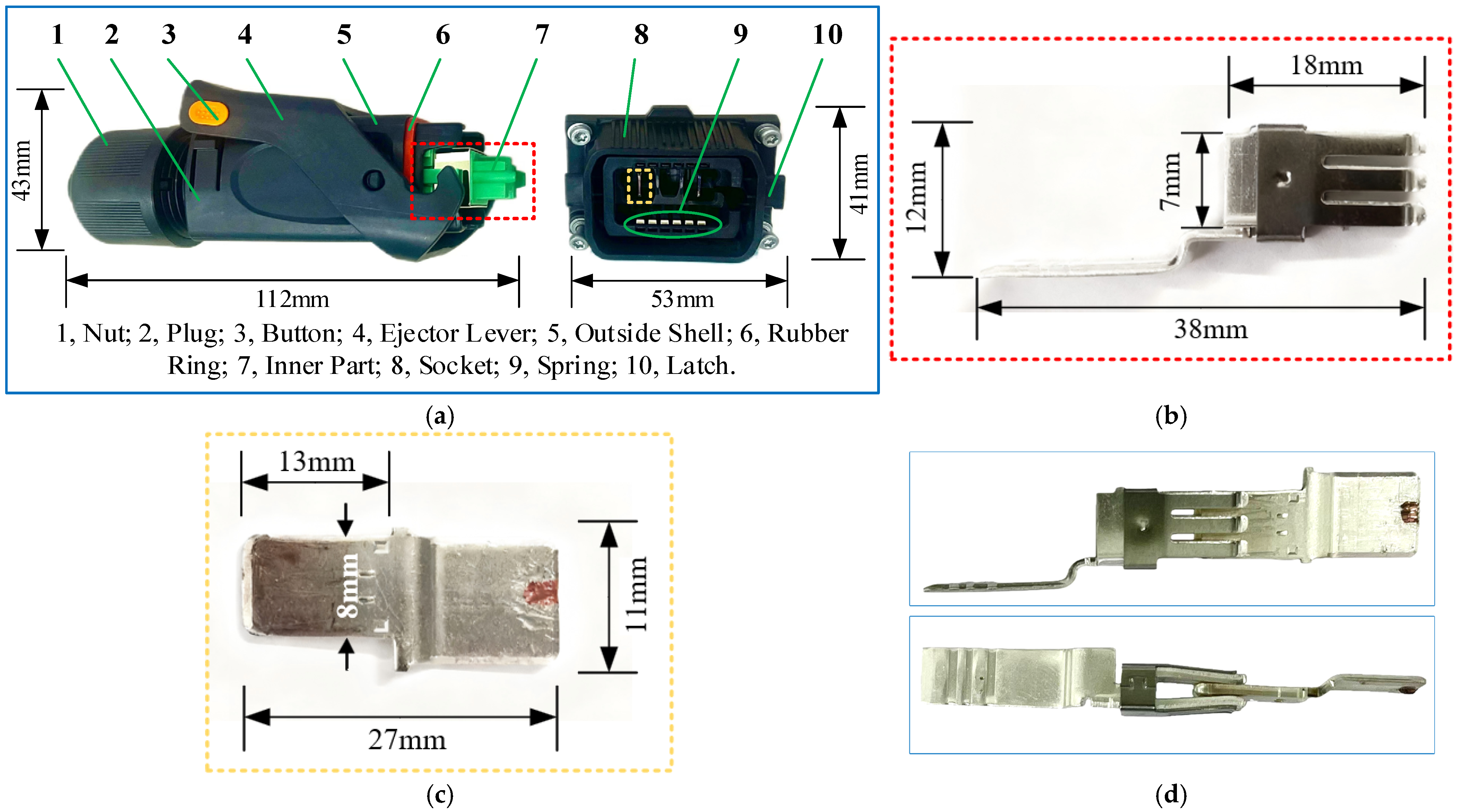

2.1. Description of Power Connectors

2.2. Test Rig

2.3. Experimental Conditions

3. Results and Discussion

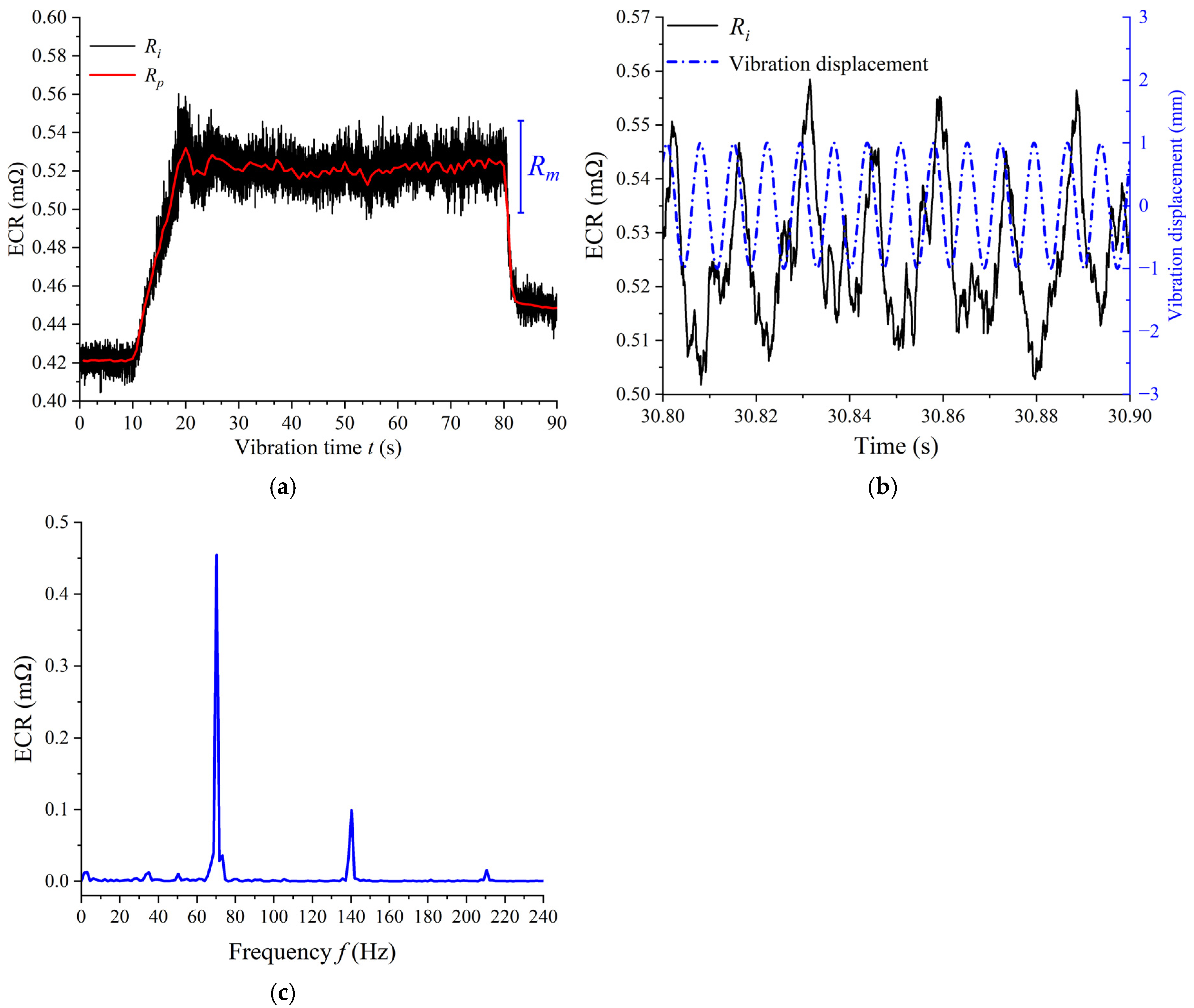

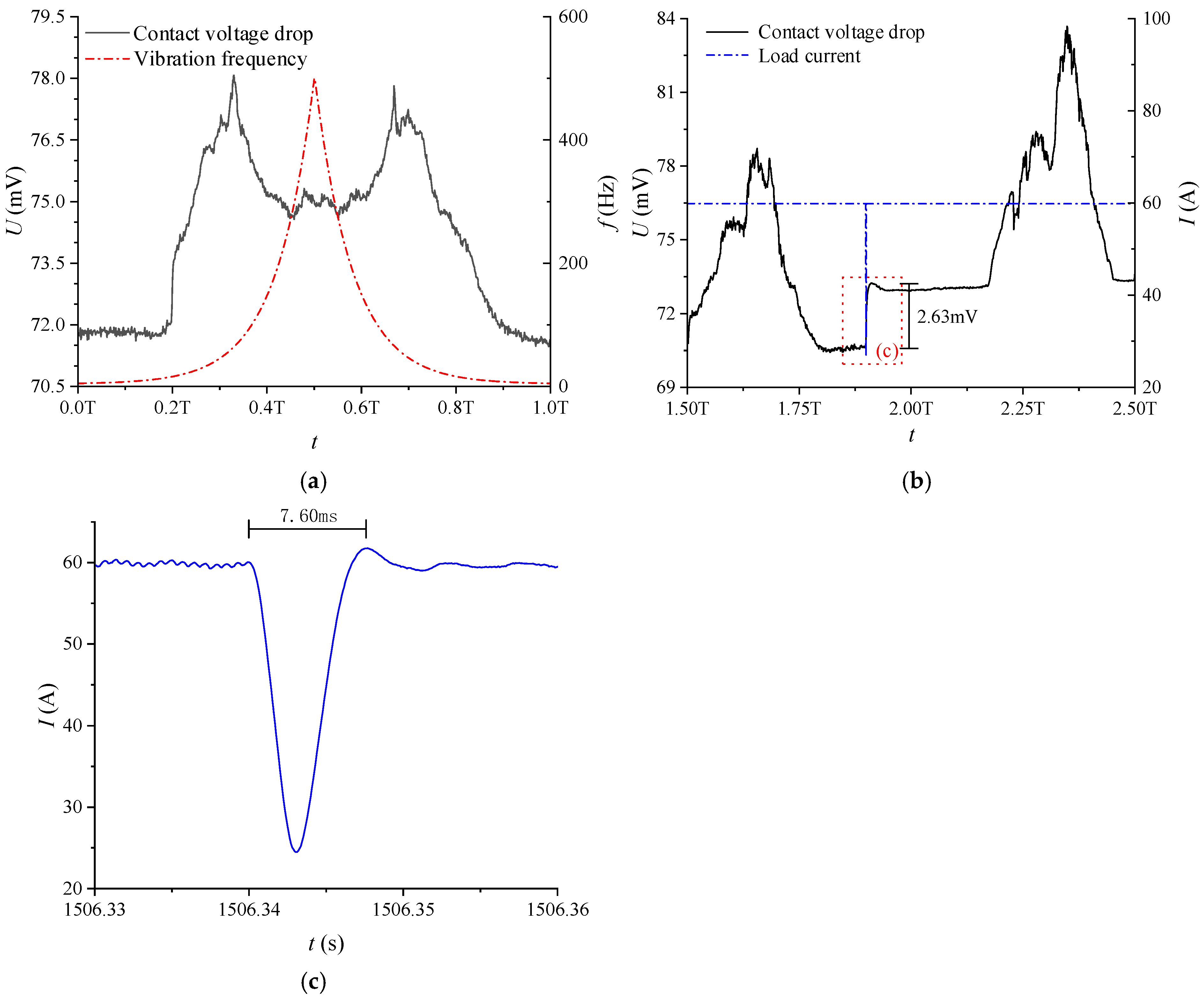

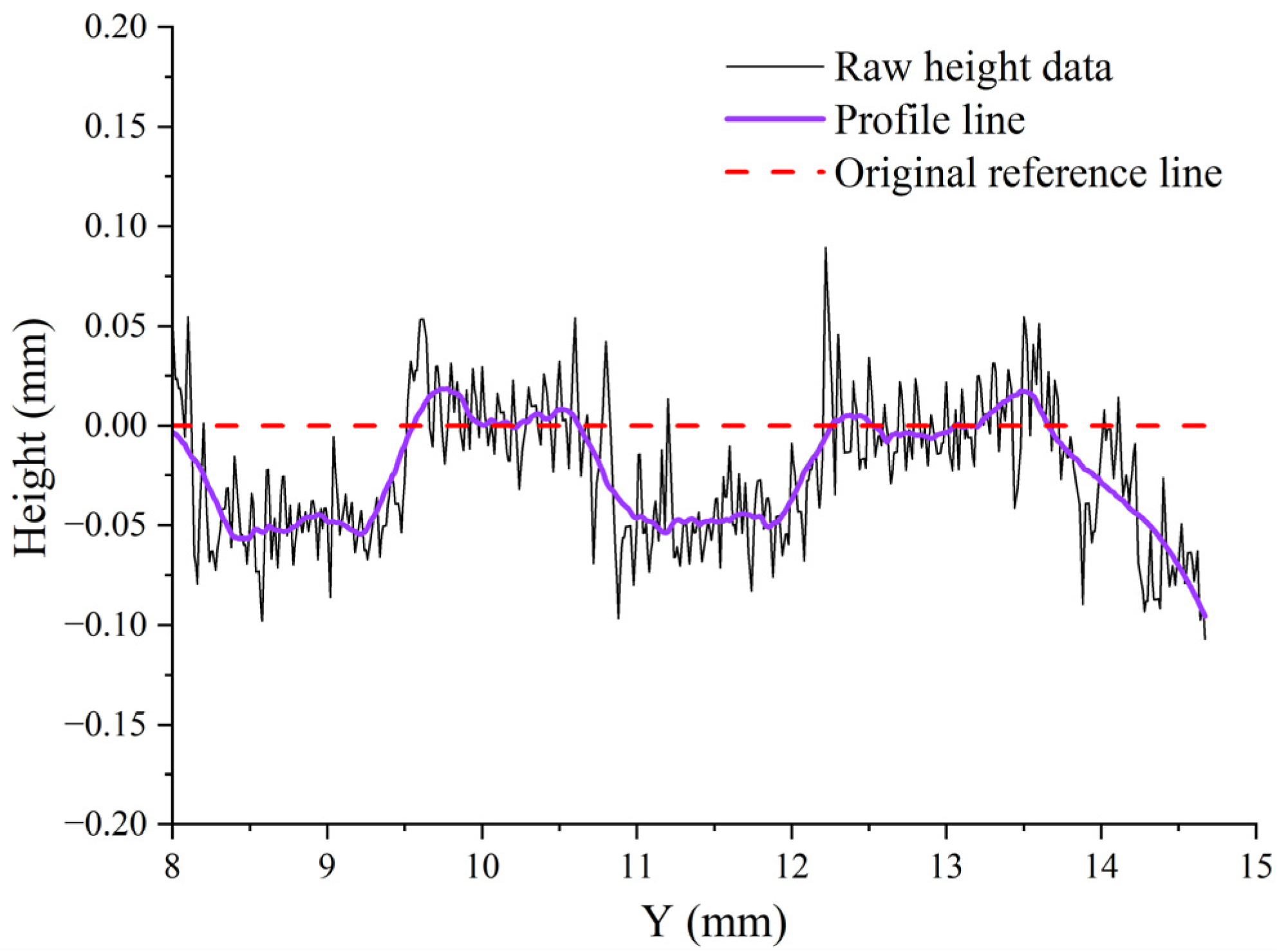

3.1. ECR Data Processing Methodology

3.2. Effect of Vibration Amplitude

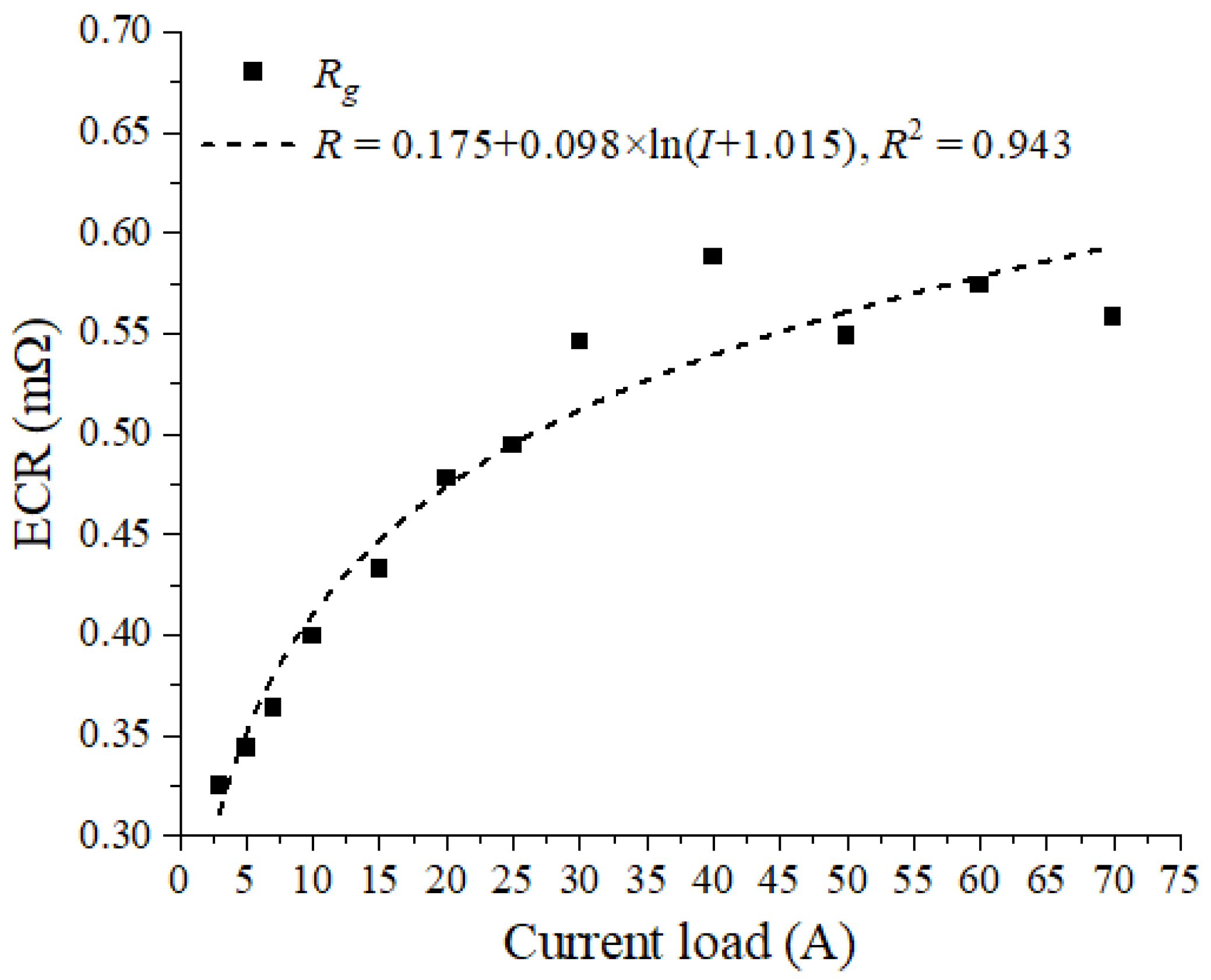

3.3. Effect of Load Current

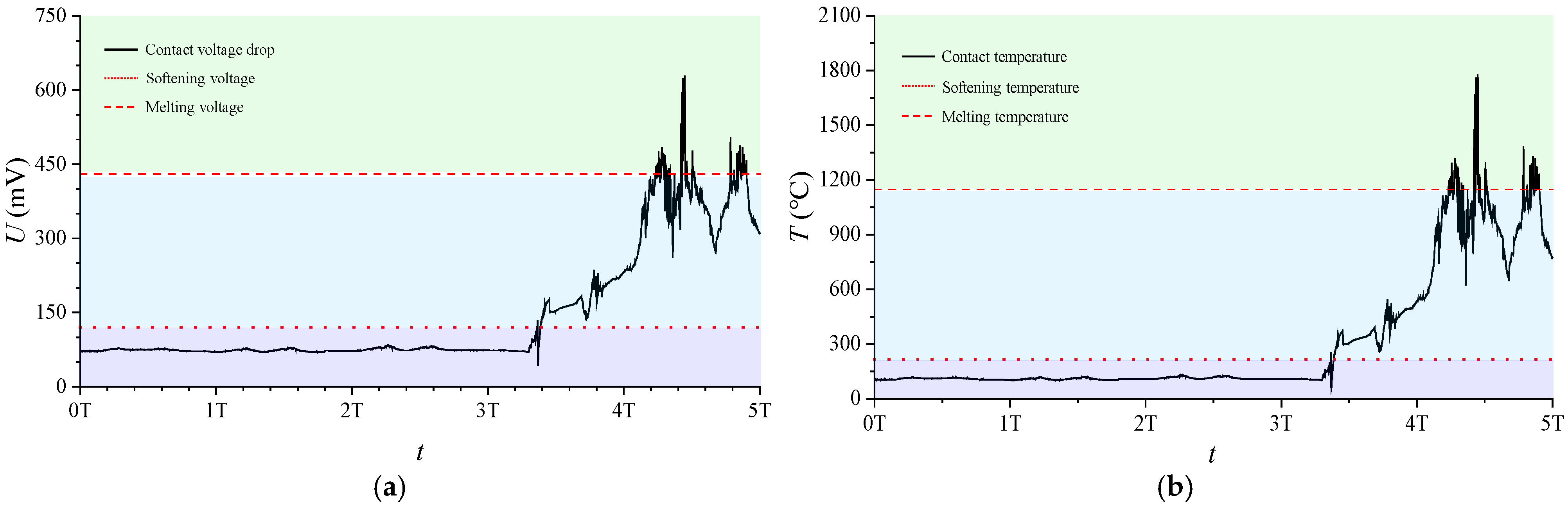

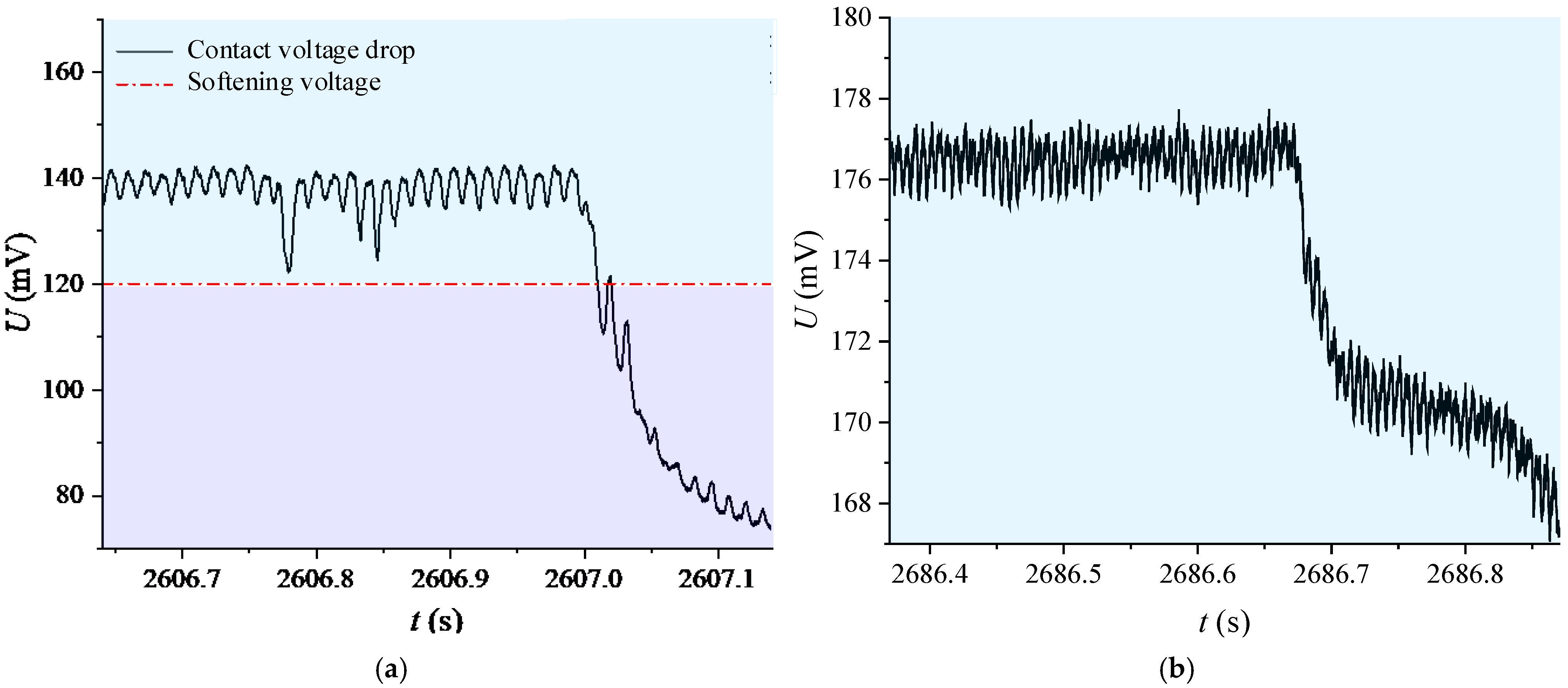

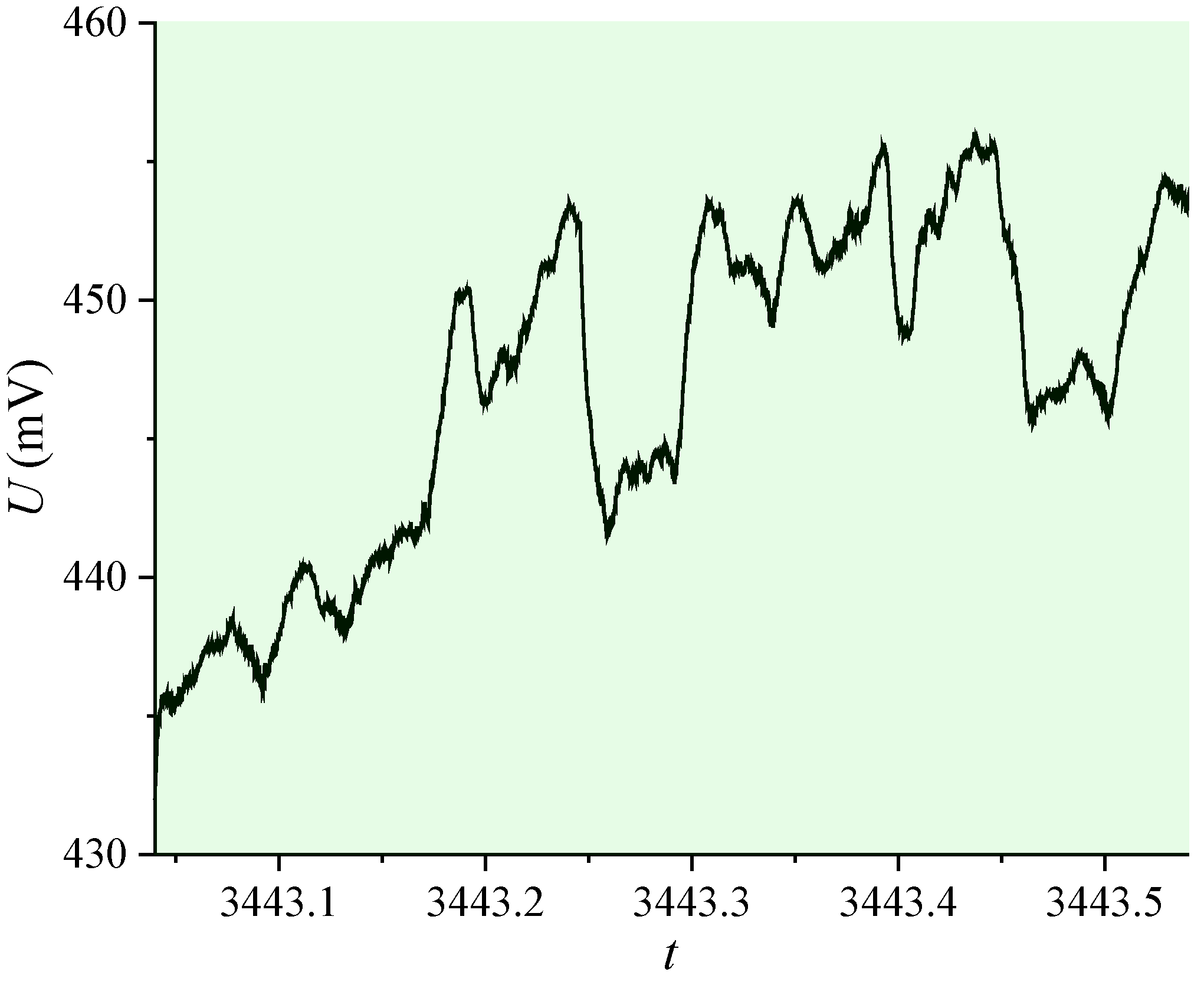

3.4. Failure Phenomena Induced by Swept-Sine Vibration Testing

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Timsit, R.S. Electrical contact resistance: Properties of stationary interfaces. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 1999, 22, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qian, L.; Peng, X.; Huang, Z.; Yang, Y.; He, C.; Fang, P. New aspects of degradation in silicone rubber under UVA and UVB irradiation: A gas chromatography–mass spectrometry study. Polymers 2021, 13, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xue, S.; Zhang, X. Electrical contact resistance of coated spherical contacts. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2016, 63, 4373–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloch, K.T.; Kozak, P.; Mlyniec, A. A review and perspectives on predicting the performance and durability of electrical contacts in automotive applications. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 121, 105143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Wang, X.; Jing, G.; Li, F.; Bai, P.; Tian, Y. Research Progress on Current-Carrying Friction with High Stability and Excellent Tribological Behavior. Lubricants 2024, 12, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Li, C.-L.; You, L.; Chen, X.-D.; He, L.-P.; Cao, Z.-Q.; Zhang, Z.-N. Prediction of contact resistance of electrical contact wear using different machine learning algorithms. Friction 2024, 12, 1250–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Shukla, A.; Probst, R. The State of Health of Electrical Connectors. Machines 2025, 12, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Cheng, X.; Lv, K.; Liu, G.; Qiu, J. Characteristics of intermittent fault in electrical connectors under vibration environment. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 10, 1575–1578. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W.; Du, D.; Du, Y. Electrical contact resistance of connector response to mechanical vibration environment. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 10, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Ben Choe, S.-Y.; Jackson, R.L.; Flowers, G.T.; Bozack, M.J.; Zhong, L.; Kim, D. Vibration-induced changes in the contact resistance of high power electrical connectors for hybrid vehicles. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2012, 2, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, L.; Li, M.; He, X.; Li, L.; Duan, M. An evaluation method for electrical contact failure based on high-frequency impedance model. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 11, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouvry, S.; Kapsa, P.; Vincent, L. Analysis of fretting wear of electrical contacts by a dissipated energy approach. Wear 1995, 185, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.W.; Narayanan, T.S.; Lee, K.Y. Fretting corrosion of tin-plated contacts. Tribol. Int. 2008, 41, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, J. Degradation behaviors of electrical connectors subjected to fretting wear under controlled environments. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 5, 1745–1754. [Google Scholar]

- Pompanon, F.; Fouvry, S.; Alquier, O. Influence of humidity on the endurance of silver-plated electrical contacts subjected to fretting wear. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2018, 354, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, C.; Hager, A.M.; Martin, J.-M. Fretting degradation of electrical contacts under high current loading: Thermomechanical coupling effects. Wear 2017, 376–377, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, M.; Saha, S.K.; Joshi, S.G.; Nakhe, P.S.; Shukla, S.K. Thermo-electrical contact degradation in high-current connectors. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 10, 1588–1597. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W.; Wang, P.; Song, J.; Zhai, G. Effects of current load on wear and fretting corrosion of gold-plated electrical contacts. Tribol. Int. 2014, 70, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shen, F.; Ke, L.-L. A comparative study on the electrical contact behavior of CuZn40 and AgCu10 alloys under fretting wear: Effect of current load. Tribol. Int. 2024, 194, 109523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.W.; Bapu, G.R.; Lee, K.Y. The influence of current load on fretting of electrical contacts. Tribol. Int. 2008, 42, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Ren, W.; Han, Y.; Zhang, C. Effects of current load on wear and melt erosion of electrical contacts under fretting condition. Tribol. Int. 2024, 194, 109511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Lv, K.; Liu, G.; Qiu, J. Dynamic performance of electrical connector contact resistance and intermittent fault under vibration. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 8, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ling, S.; Li, D.; Zhai, G. Vibration-induced dynamic characteristics modeling of electrical contact resistance for connectors. Microelectron. Reliab. 2020, 114, 113868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.H.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Zhang, Z.Z. Simulation and experimental study of the influence of temperature stress on the intermittent fault of an electrical connector. Exp. Tech. 2019, 43, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Z.; Shen, F.; Feng, X.; Ke, L.-L. Evolution of electrical contact status and wear pattern under various loading conditions for copper-beryllium alloy. Wear 2025, 544, 206366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunovic, M.; Konchits, V.V.; Myshkin, N.K. Electrical Contacts: Fundamentals, Applications and Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 149–203. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y.; Ren, W.; Zhang, C. A Degradation Model of Electrical Contact Performance for Copper Alloy Contacts with Tin Coatings Under Power Current-Carrying Fretting Conditions. Coatings 2024, 14, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P.G. Electrical Contacts: Principles and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.W.; Joo, H.G.; Lee, K.Y. Effect of intermittent fretting on corrosion behavior in electrical contact. Wear 2010, 268, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, J.; Perrinet, O.; Fouvry, S. Prediction of the electrical contact resistance endurance of silver-plated coatings subject to fretting wear, using a friction energy density approach. Wear 2015, 330–331, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Shi, Y.; He, X.; Chen, X.; Duffy, A.; Zhu, M.; Han, Z.; Wang, L. The effect of corrosion on the electrical contact performance of aviation connectors revealed by in situ impedance measurements. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 15, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, K.; Matthews, A.; Ronkainen, H. Coatings tribology: Contact mechanisms and surface design. Wear 2003, 254, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liskiewicz, B.; Neville, A. Fretting wear of gold-plated electrical contact materials: The influence of interfacial oxidation. Tribol. Int. 2010, 43, 150–159. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Vibration frequency | 5 Hz~1000 Hz |

| Vibration amplitude | 0.5 mm~5 mm |

| Environment temperature | 25 °C |

| Current load | 3~70 A |

| Humidity | 62 ± 2% RH |

| Element | I | II | III |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | 98.06 wt% | 13.34 wt% | 7.34 wt% |

| Ni | 0 | 39.13 wt% | 2.52 wt% |

| Cu | 0 | 28.47 wt% | 74.22 wt% |

| O | 1.94 wt% | 19.06 wt% | 15.92 wt% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Sun, C.; Ren, W.; Liao, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, J. Current-Carrying Performance Degradation Mechanisms of Outdoors Power Connectors Under External Vibrations. Vibration 2025, 8, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration8040077

Zhang C, Sun C, Ren W, Liao Y, Li M, Liu J. Current-Carrying Performance Degradation Mechanisms of Outdoors Power Connectors Under External Vibrations. Vibration. 2025; 8(4):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration8040077

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Chao, Chang Sun, Wanbin Ren, Yuchen Liao, Ming Li, and Jian Liu. 2025. "Current-Carrying Performance Degradation Mechanisms of Outdoors Power Connectors Under External Vibrations" Vibration 8, no. 4: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration8040077

APA StyleZhang, C., Sun, C., Ren, W., Liao, Y., Li, M., & Liu, J. (2025). Current-Carrying Performance Degradation Mechanisms of Outdoors Power Connectors Under External Vibrations. Vibration, 8(4), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration8040077