The integrated elevated station, which incorporates building and bridge constructions, results in significant disparities in structural stiffness and mass distribution, both horizontally and vertically. This integration poses issues such as complex load transfer channels, elucidating dynamic coupling from train vibrations, and an absence of standardised design protocols during the design phase. A multitude of scholars have investigated these challenges, conducting comprehensive on-site studies at elevated stations. Cai et al. [

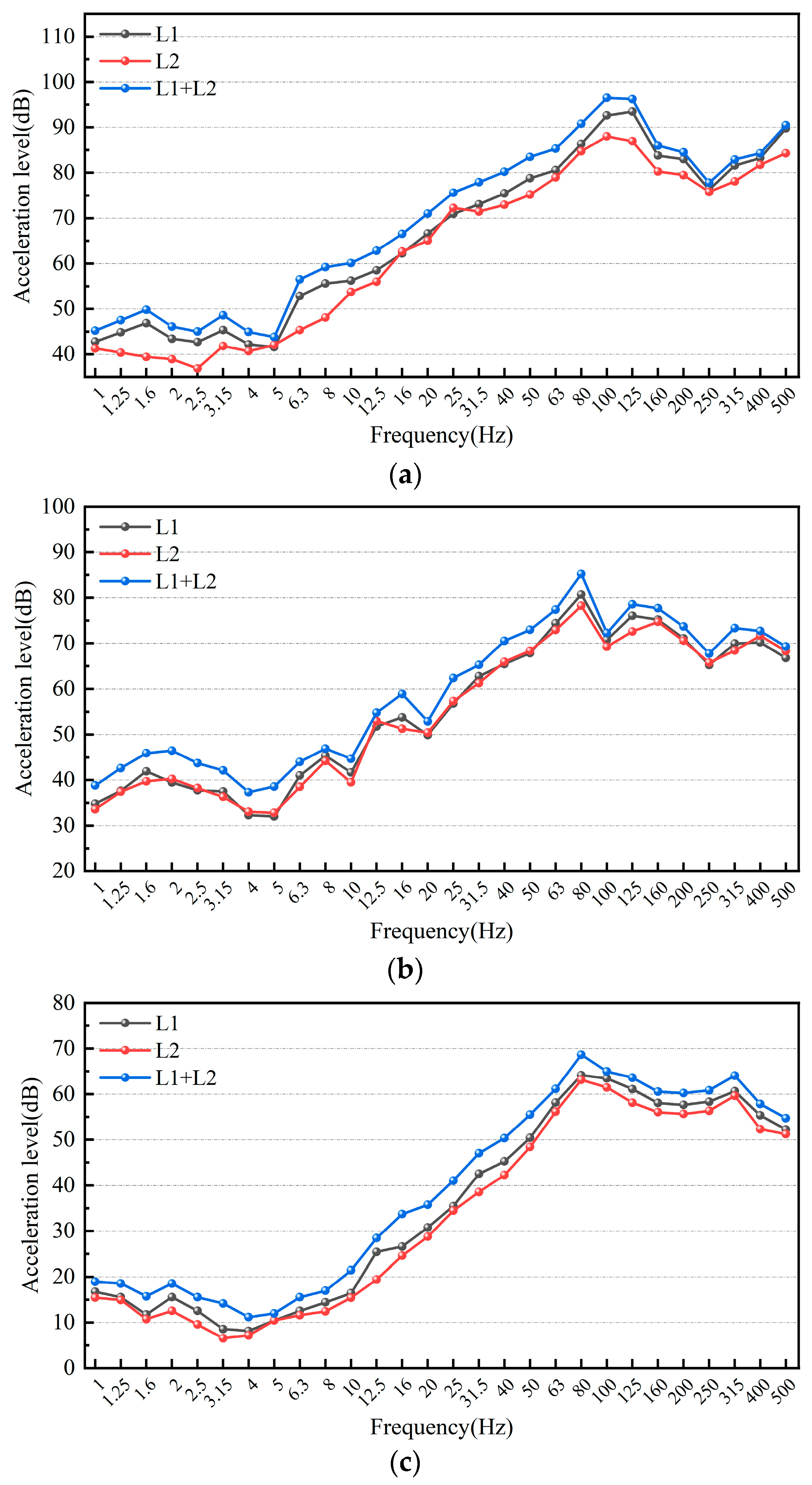

2] examined the vibration properties of elevated stations, analysing vibrations in waiting areas and platforms throughout temporal and frequency domains. They identified variations in vibration responses attributable to trains arriving, departing, and traversing. Yu et al. [

3] examined the effects of high-speed train loads on waiting room and commercial floors’ vibrations, assessing vibration serviceability with data from Zhengzhou East Railway Station. Liu et al. and Yang et al. [

4,

5] conducted tests and analyses on environmental vibrations in various areas of elevated stations, including platforms and waiting halls, to explore the propagation of train-induced vibrations. Ba et al. [

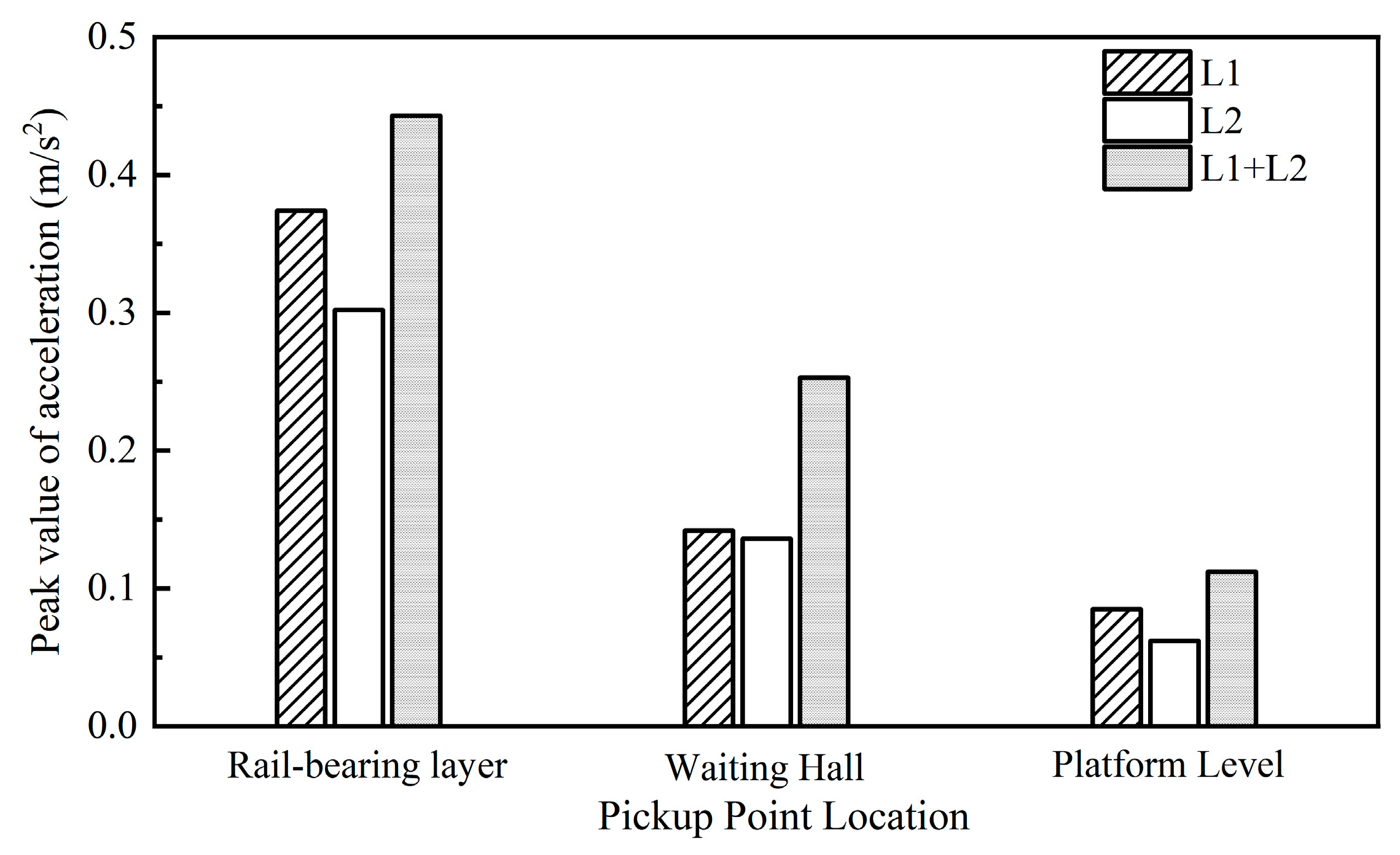

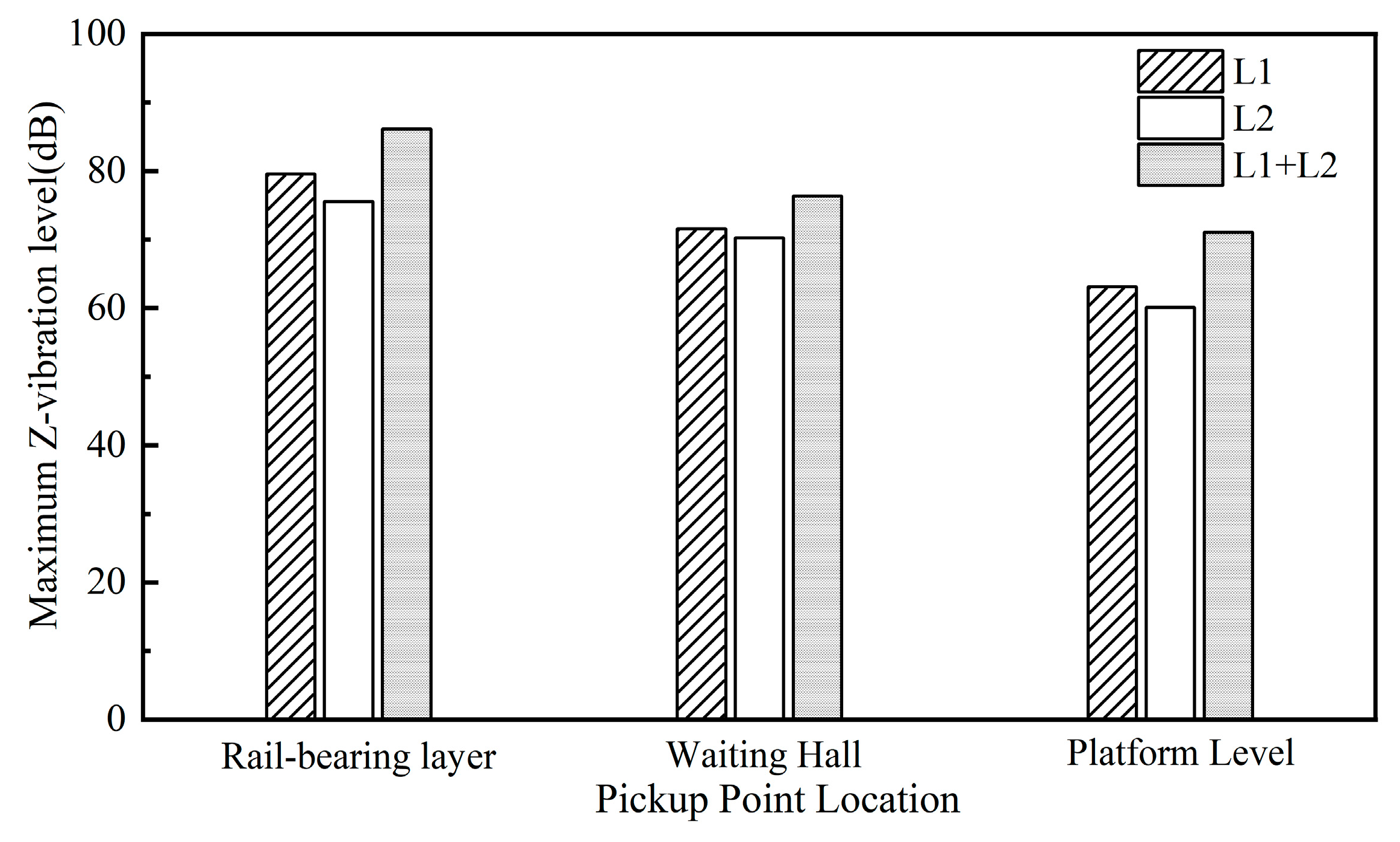

6] conducted field tests to assess background and structure vibrations at diverse speeds, evaluating effective vibration acceleration at multiple locations. Furthermore, high-speed trains impact nearby buildings with vibrations [

7,

8,

9]. Xia et al. [

10,

11] explored the mechanisms behind train-induced vibrations at elevated stations, examining the effects of train type, speed, and proximity on nearby buildings. Sanayei et al. and Hesami S et al. [

12,

13] corroborated finite-element models with field data, studying the impact of train speed, soil properties, and structural traits on building vibrations caused by trains. Li et al. [

14] performed empirical research on vibrations and noise at large high-speed railway stations due to passing trains, exploring structural vibration patterns during train operations. Other researchers have proposed various numerical models for simulation calculations. Deng et al. [

15] suggested taking the load time-history from the train–bridge sub-model dynamic calculations as the external excitation acting on the bridge–station sub-model. They conducted time-history analysis to compute the dynamic response caused by trains passing through the elevated station and evaluated the station’s vibration serviceability. Xu et al., Xie et al., Yang et al., and Cui et al. [

16,

17,

18,

19] established a train–station vibration analysis system to explore station dynamics and train-induced vibration patterns, focusing on station structure vibration level. Alan and Caliskan [

20] investigated vibration control for train-induced vibrations at an Ankara station. They simulated the station–foundation interaction with springs and dampers in a finite-element model, aligning with Turkish environmental noise laws. Zhang et al. [

21] used rigid body dynamics for a train subsystem-model and the mode superposition method for a structural model. They explored the analysis method for the train–station structure coupling system under braking force. Zhang et al. [

22] devised a numerical model for analysing vibrations in large-scale integrated building–bridge structures (IBBS), focusing on HSR stations and evaluating vibration mitigation effectiveness. Yang et al. [

23] introduced a two-step time-frequency prediction method for superstructures to predict and analyse train-induced vibrations in buildings above subway tunnels. Liang et al. [

24] utilised a physics-informed deep learning approach to investigate the structural dynamic reaction to moving loads, with the objective of improving the precision of forecasting structural vibration responses under these loads. Xu et al. [

25] investigated the measurement of vibration source intensity produced by subway trains on conventional and floating slab tracks, and provided an effective approach for determining the vibration source intensity generated by these trains. Liang et al. [

26] investigated the propagation characteristics of ground vibrations caused by train operations and provided an effective model for predicting ground vibrations. Ma et al. [

27] concentrated on the intricate transmission pathway of “overlapping subway lines-strata-historical buildings” by utilising on-site vibration measurements and statistical data analysis to examine the response patterns of train vibrations on historical structures and evaluate the extent of vibration impact. Qu et al. [

28] conducted a thorough examination of the complete propagation chain of subway vibrations, integrating empirical data with theoretical research. They performed categorization, identification, and quantitative analysis of multiple elements that may induce vibration variability and pinpointed the principal contributing factors. Guo and Wang [

1] studied the structural dynamic characteristics of the multi-line bridge-integrated elevated station. Numerous researchers have explored the vibration characteristics of station structures during train operations, including aspects of safety and environmental vibration level. Li [

29] proposed an optimisation strategy for bearing stiffness in the frame-type “bridge-building integration” structure to control environmental vibration. Feng et al. [

30] examined railway station structures, collected data via vibration measurements during train transit, assessed environmental vibration according to the ISO 2631-1 standard, and suggested strategies for environmental vibration control, including increasing structural damping and modifying track fastener stiffness. Gao and Li [

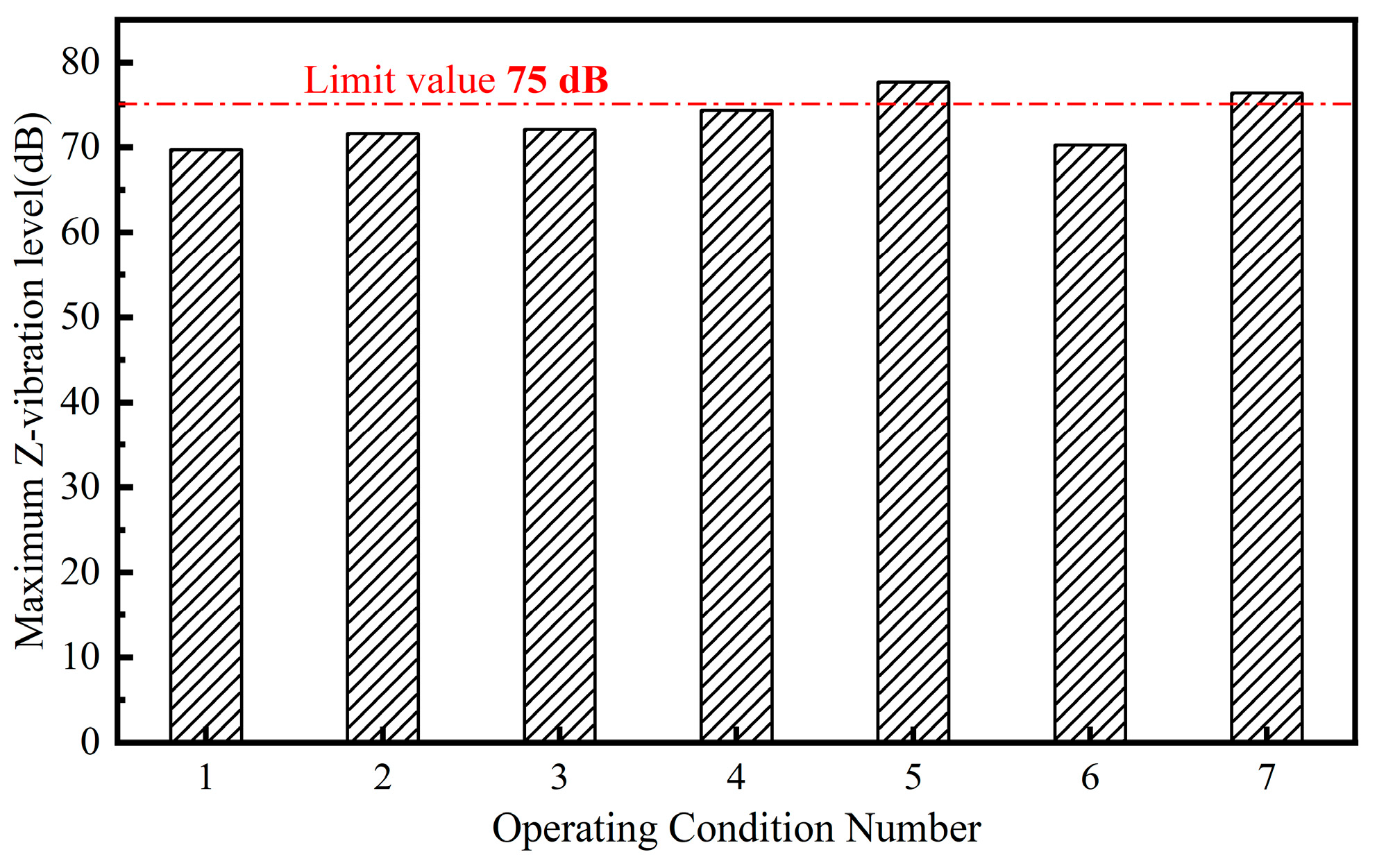

31] focused on the vibration issues caused by traffic loads in elevated stations, analysed its impact on the environmental vibration of station areas, and recommended adopting track vibration reduction measures to control environmental vibration. Zhao et al. [

32] conducted shaking table tests to study the seismic performance of the integrated bridge-station structure. By comparing the dynamic responses under different seismic wave inputs, they discovered the development pattern of plastic hinges in key structural locations (such as beam–column joints) and proposed a displacement-based seismic design method to enhance overall ductility. Xie et al. [

33] conducted a study on the impact of vibration induced by pedestrian activities on environmental vibration in the elevated waiting hall of Fengtai Station in Beijing. They proposed a scheme to control environmental vibration of the waiting hall by adding tuned mass dampers (TMDs) and optimising the structural stiffness distribution. Cui and Su [

34] established a finite-element model for the elevated station–track coupling system to study the impact of vibration response on environmental vibration under resonance conditions. They revealed that when the wavelength of track irregularities matches the natural frequency of the structure, it can amplify vibrations and seriously aggravate environmental vibration. They proposed an environmental vibration control strategy by adjusting track stiffness and increasing structural damping to avoid the resonance range. Despite extensive research on bridge-station integrated structures, existing studies have critical gaps that highlight the necessity of this work—especially for the novel vertical-integrated system with the waiting hall directly beneath tracks. Key limitations are summarised as follows: First, research objects focus on traditional/simplified structures, not the novel vertical-integrated system. Most studies [

1,

2,

3,

6] target “building-bridge separated” or “simplified integrated” designs, where waiting halls are not under tracks. These lack the novel system’s significant stiffness/mass disparities and complex vertical load transfer paths, leaving its dynamic characteristics unaddressed. Second, mechanistic analysis of dynamic coupling is superficial, with no quantitative exploration of key factors. Prior work [

2,

3,

10] remains phenomenological, failing to quantify impacts of structural joints, double-line operation, or 350 km/h speeds on track-waiting hall coupling—the novel system’s core challenge. Vibration mitigation strategies [

30,

34] are general, not tailored to its unique needs. Third, numerical models are ill-suited for high-integration structures. Existing models [

15,

22] were developed for conventional designs and lack validation for the “waiting hall under tracks” configuration, limiting reliable design tools. Fourth, high-speed adaptability and scenario-specific environmental vibration assessment are inadequate. Most tests [

3,

6] are ≤300 km/h, with no targeted environmental vibration level analysis for the novel system’s exposed waiting hall or comparisons of single/double-line operations. In summary, existing research does not address the novel structure’s dynamic mechanisms, key influencing factors, or high-speed environmental vibration performance. This study is necessary to fill these gaps, providing theoretical and engineering support for its design and optimisation.

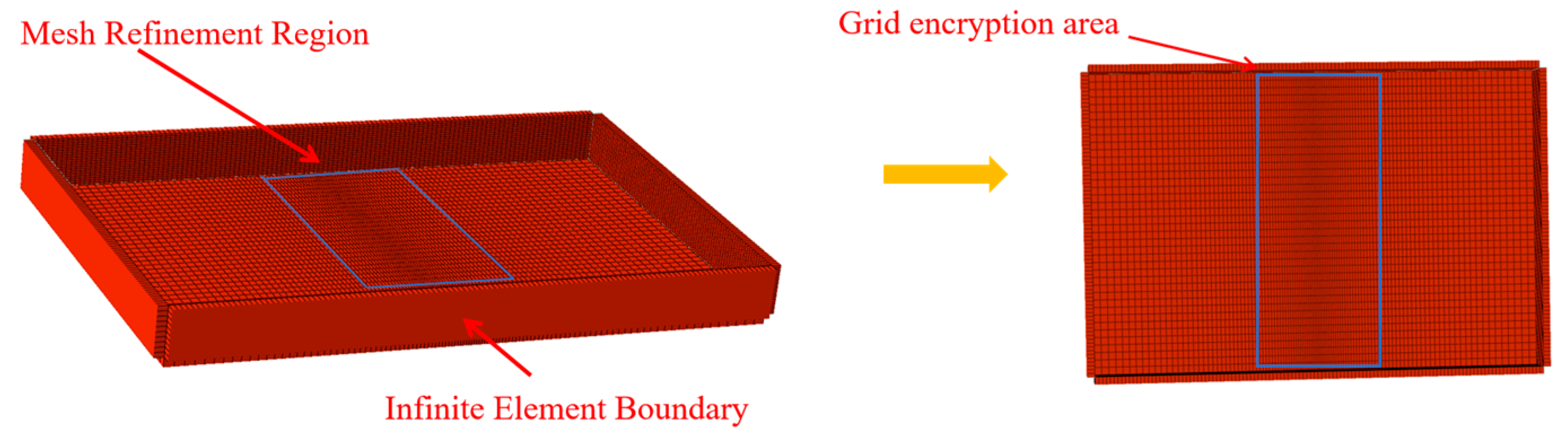

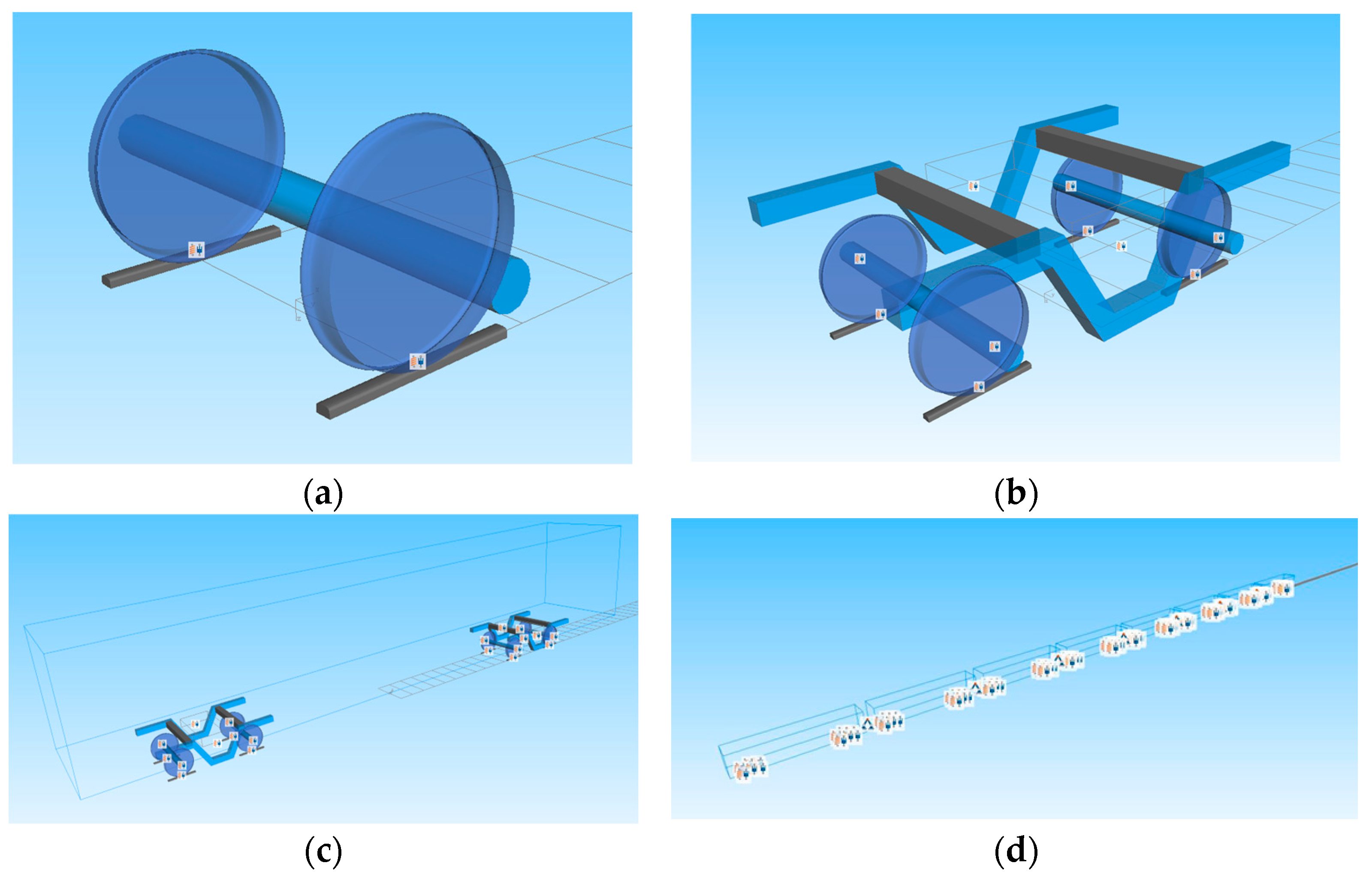

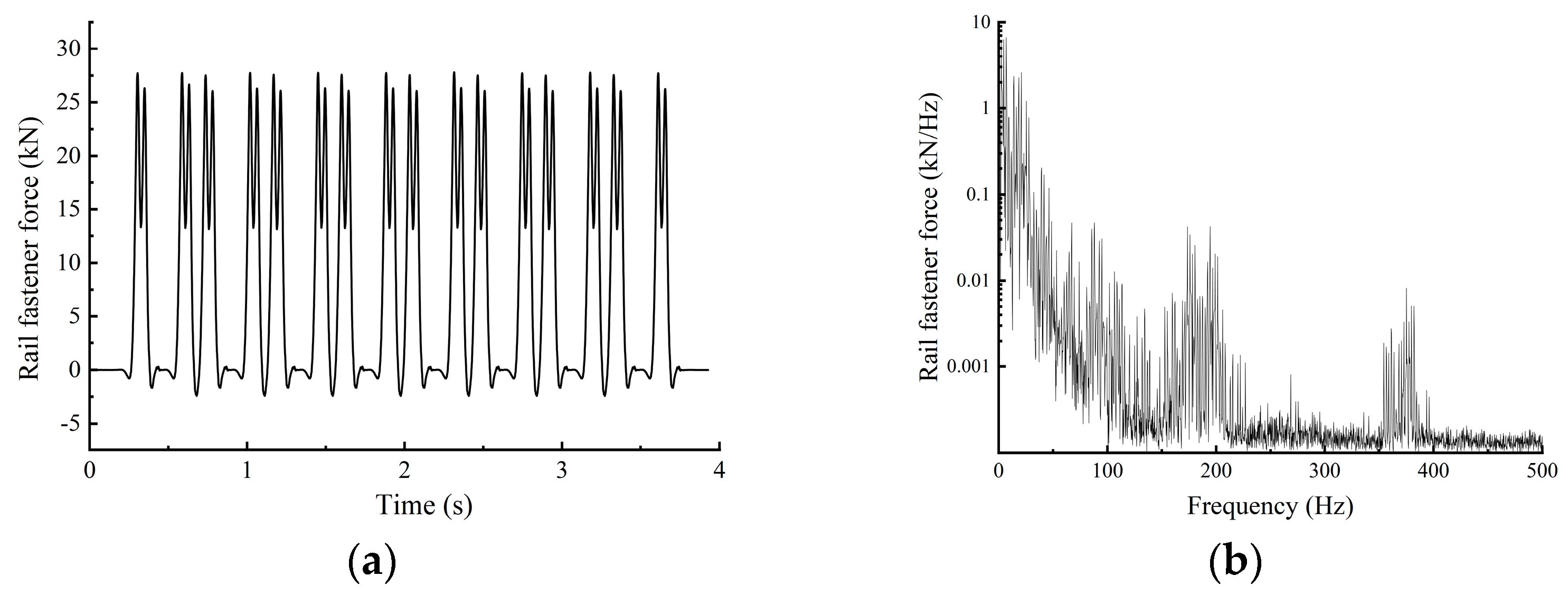

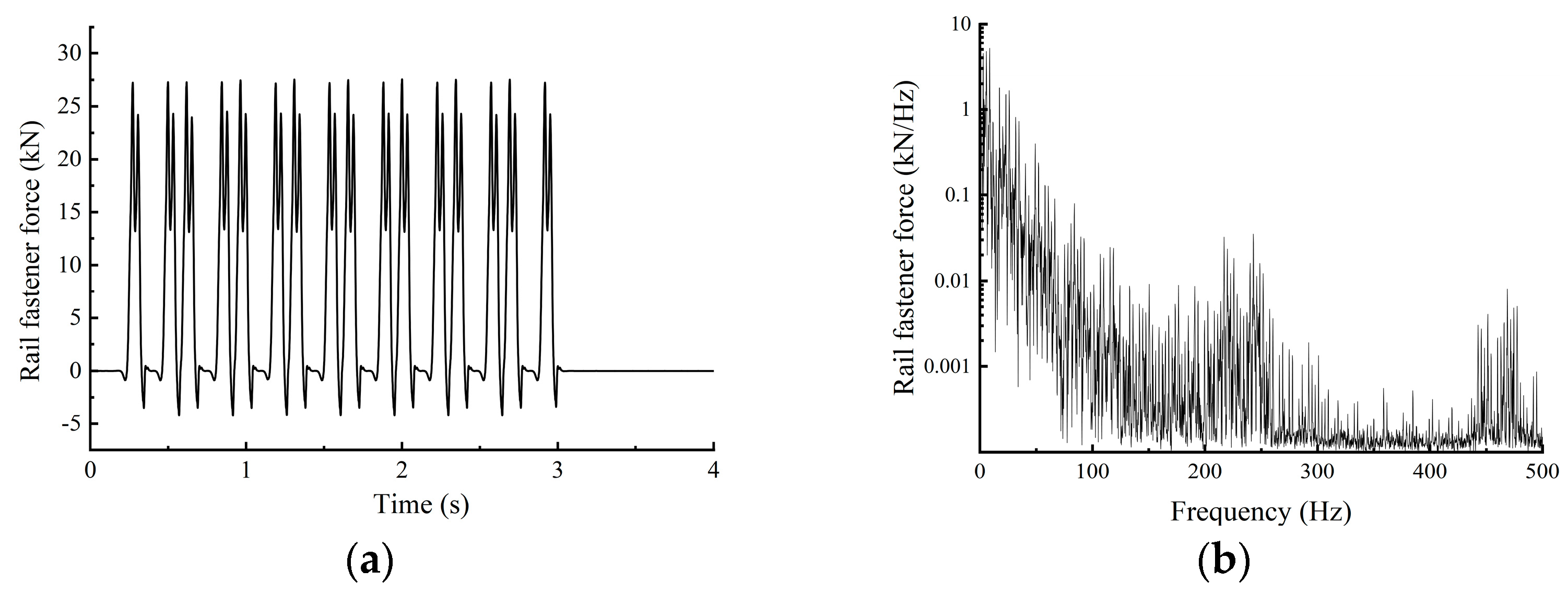

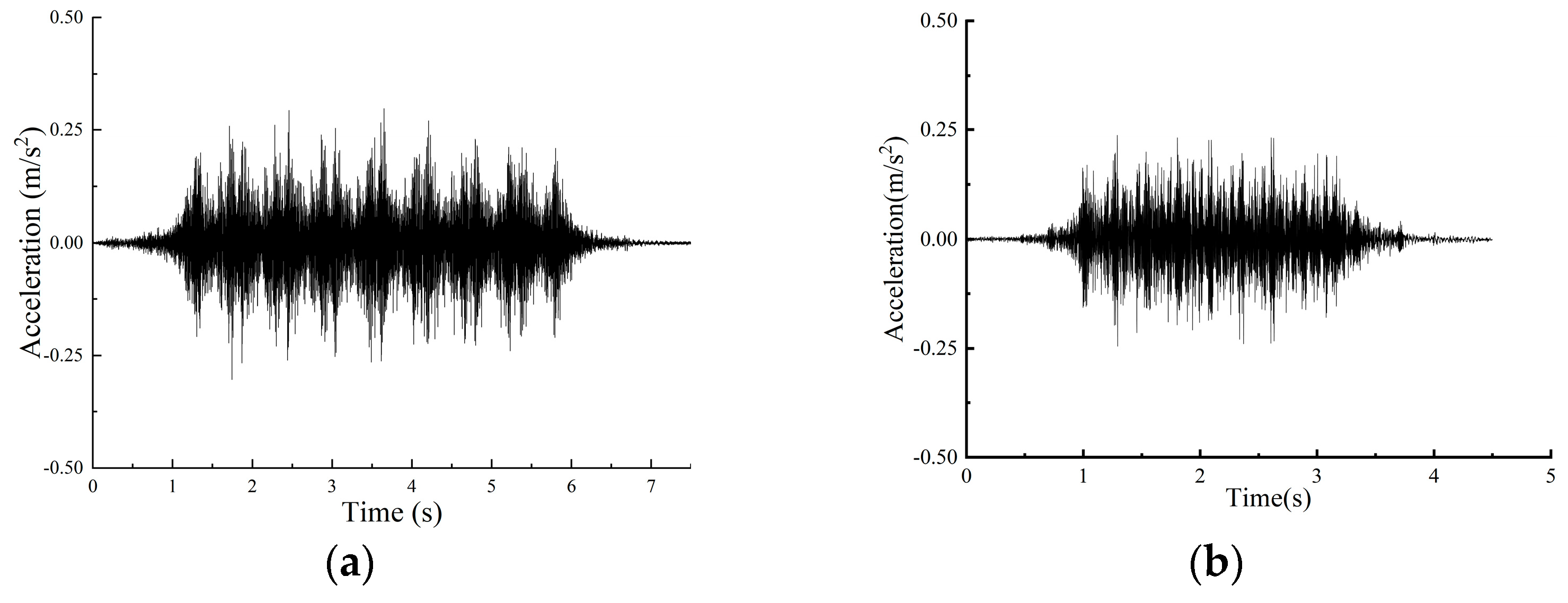

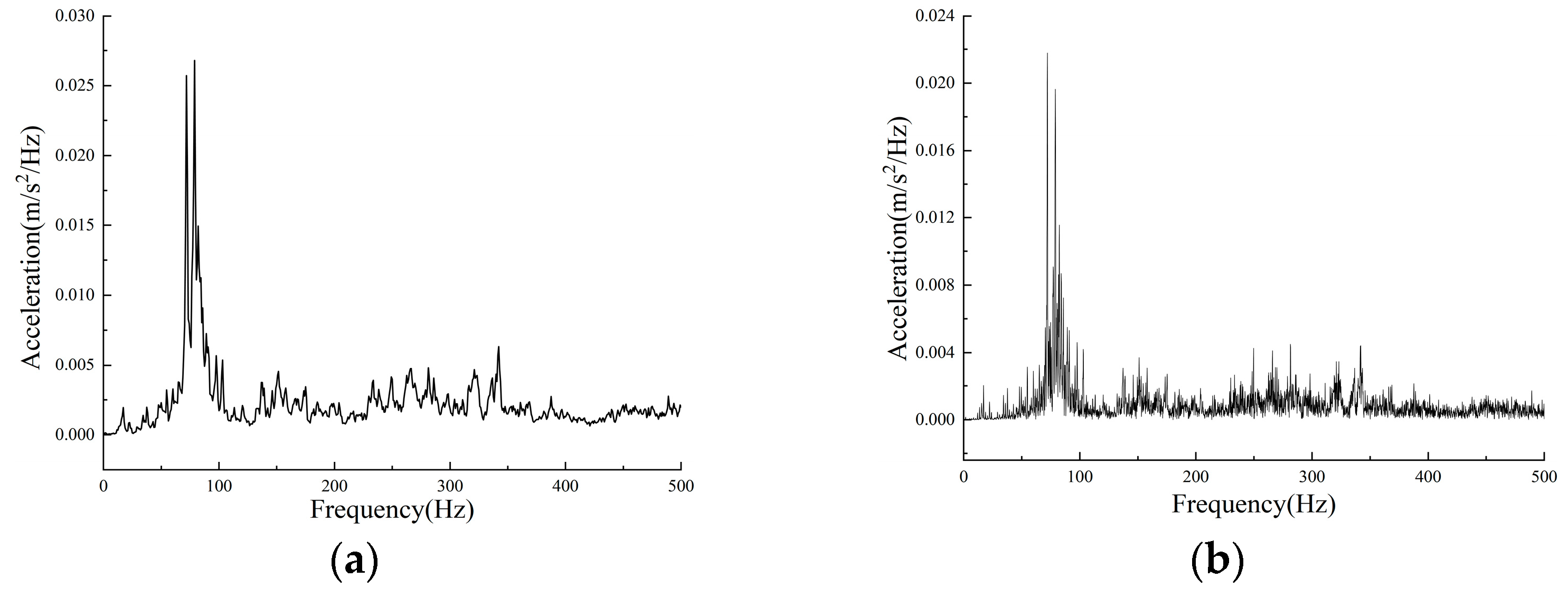

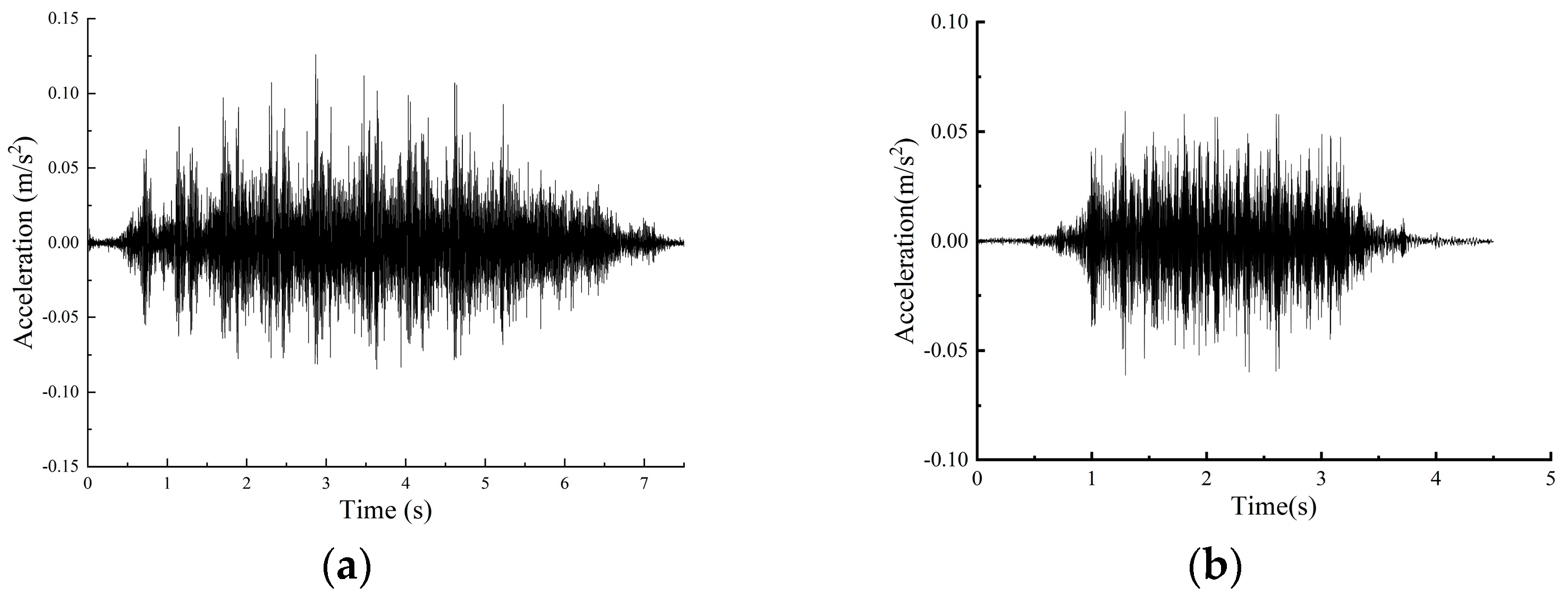

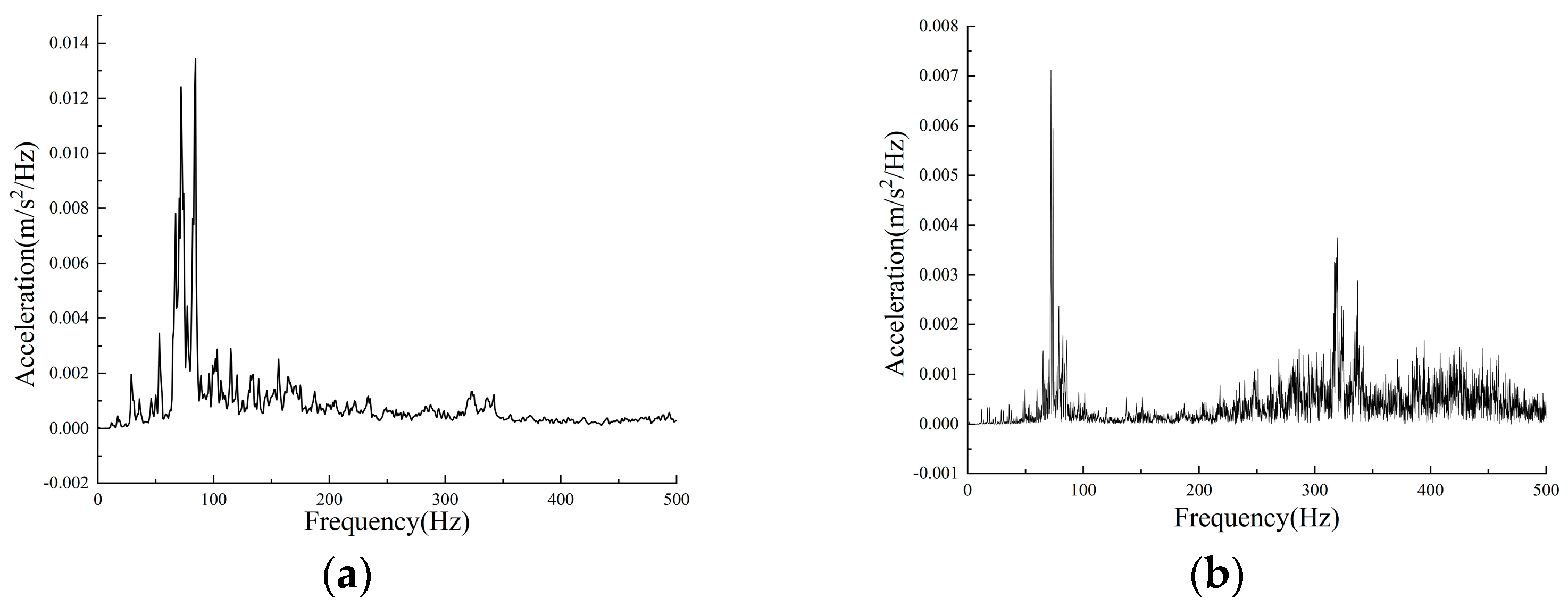

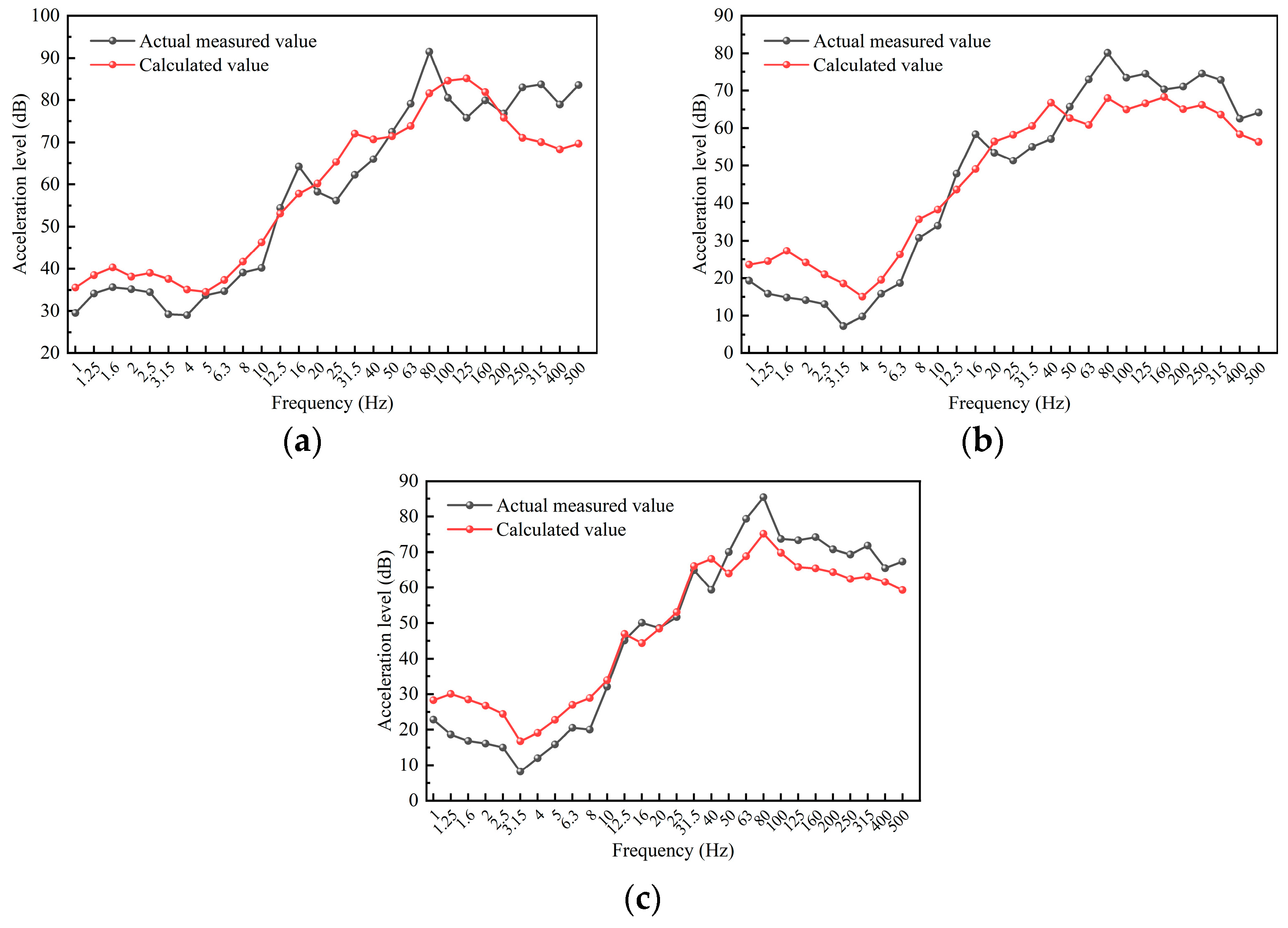

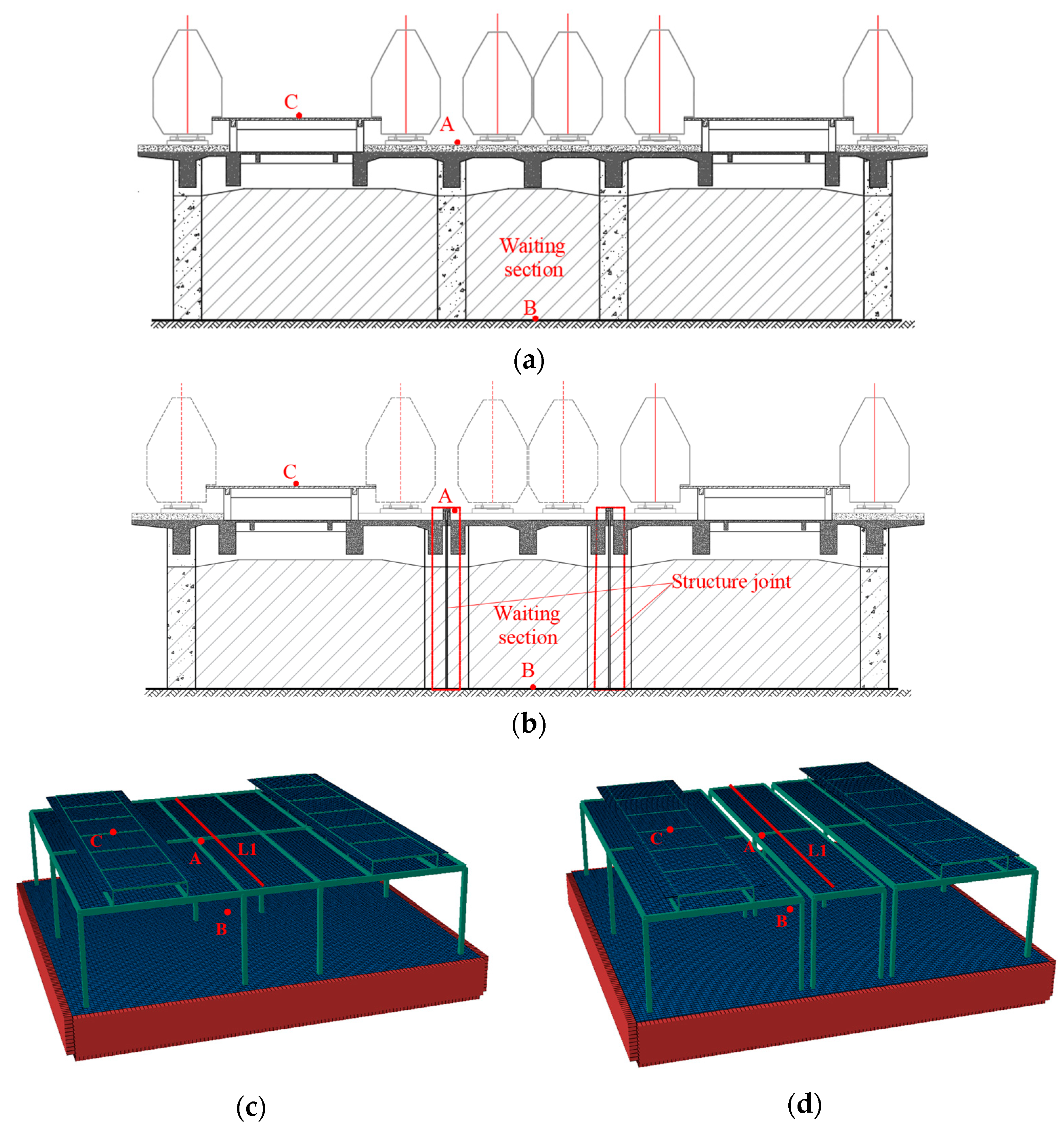

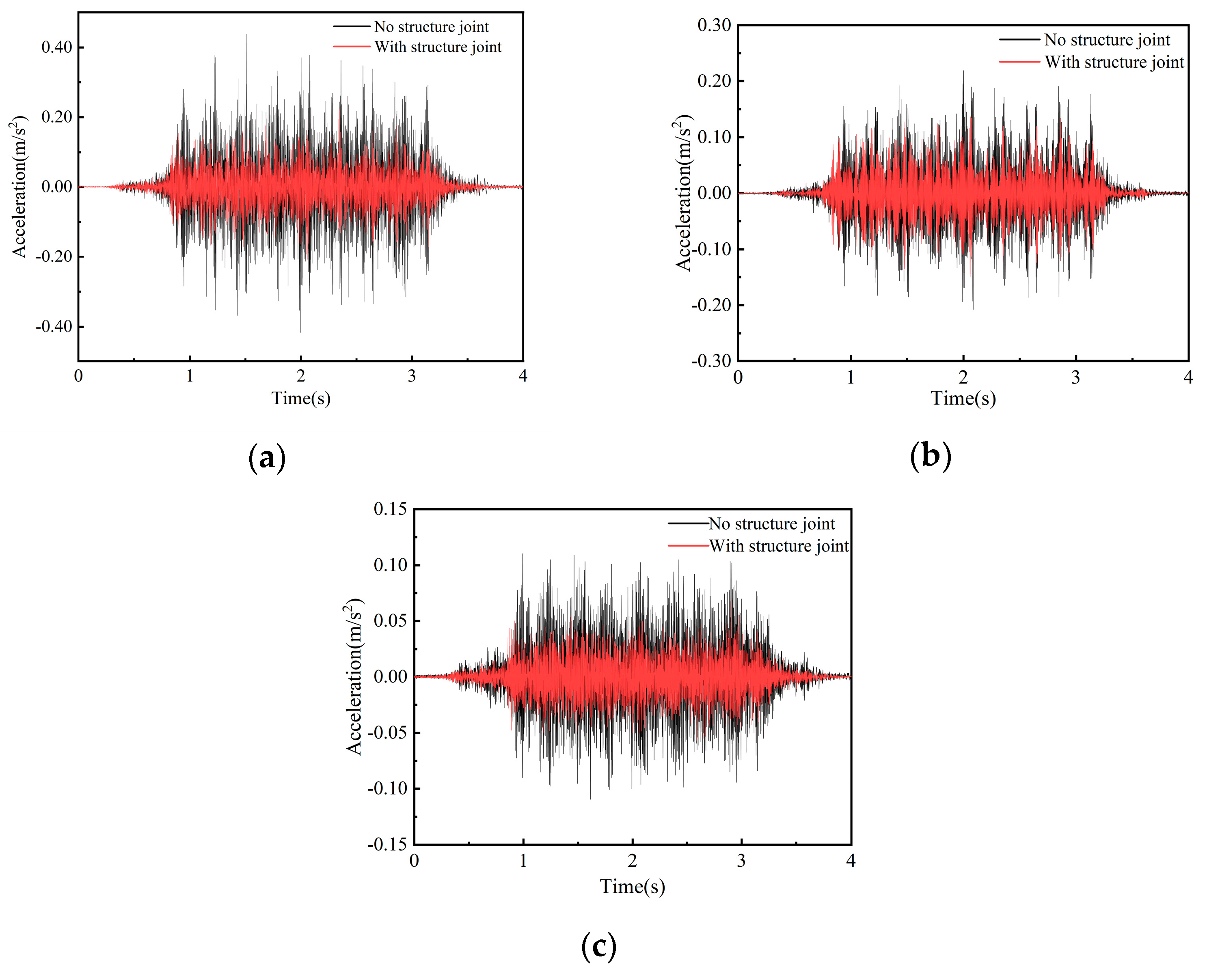

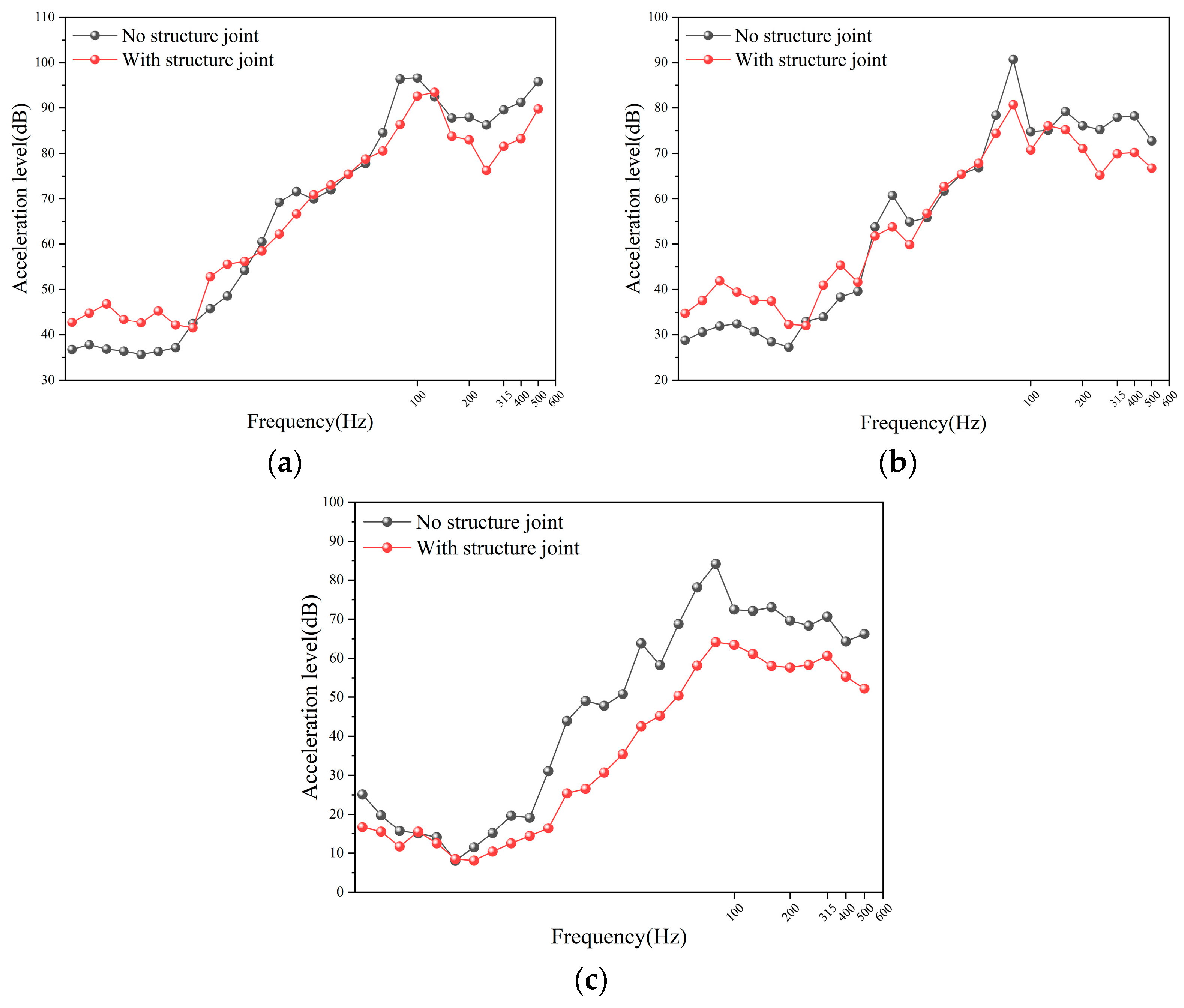

Therefore, this study takes a new type of elevated station that integrates bridge and building as the research object. A model for high-speed train–track coupling is developed utilising a rigid–flexible coupling methodology, and the vibration load of high-speed trains is analysed using Simpack 2021. The model’s accuracy is validated using empirical data. A three-dimensional dynamic numerical model of the station is developed utilising Abaqus 2022 software, with the model construction methodology and parameter selection validated against empirical data. A comparative analysis of vibration propagation patterns and their affecting elements is performed for the innovative “integrated bridge and building” elevated station structure, and the vibration environment within the waiting hall is assessed. The insights obtained can serve as a reference and foundation for the structural optimisation design of new elevated stations.