Wildland Firefighter Heat Stress Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

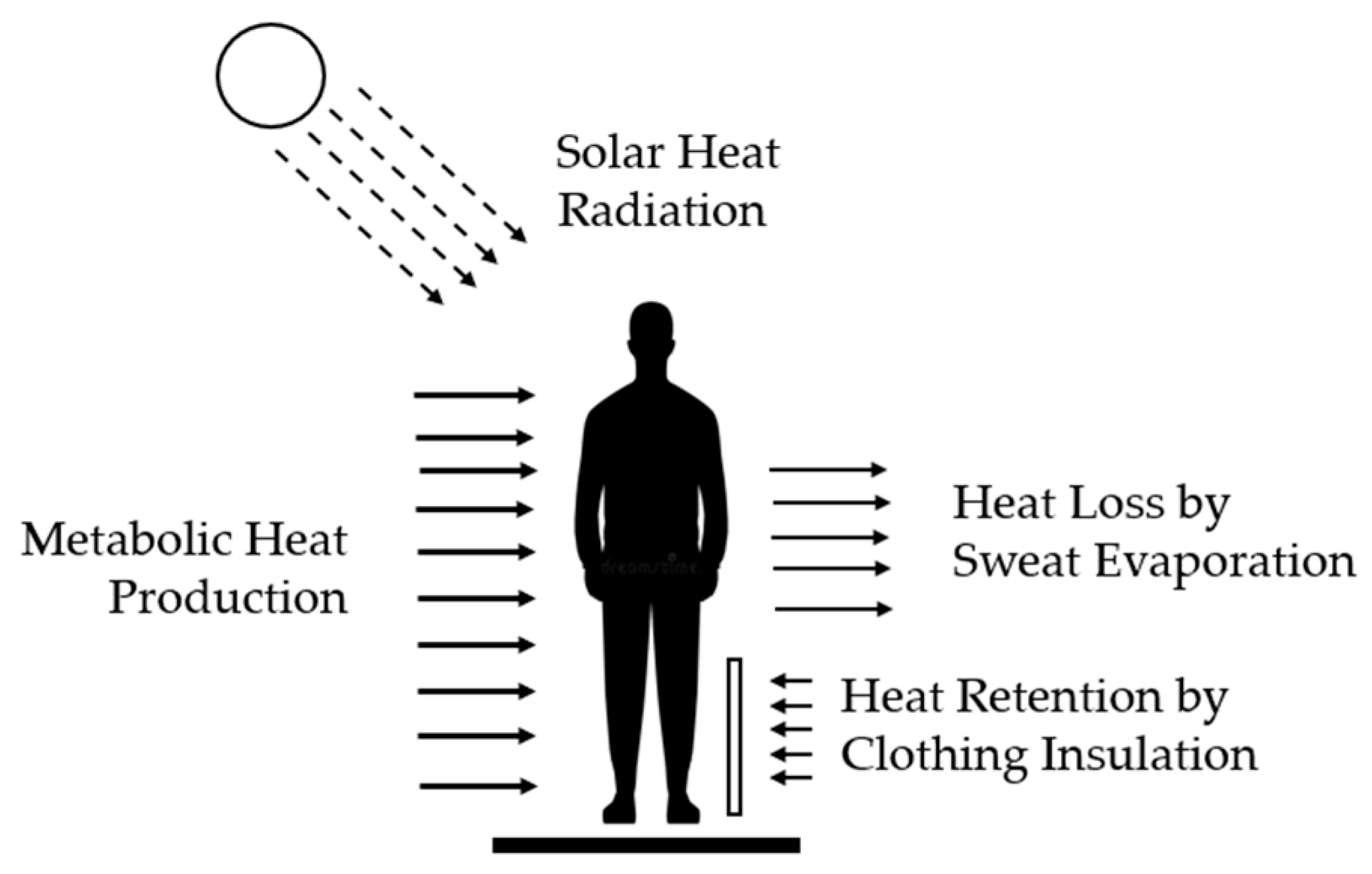

2. Heat Stress

3. Environmental Factors

4. Occupational Factors

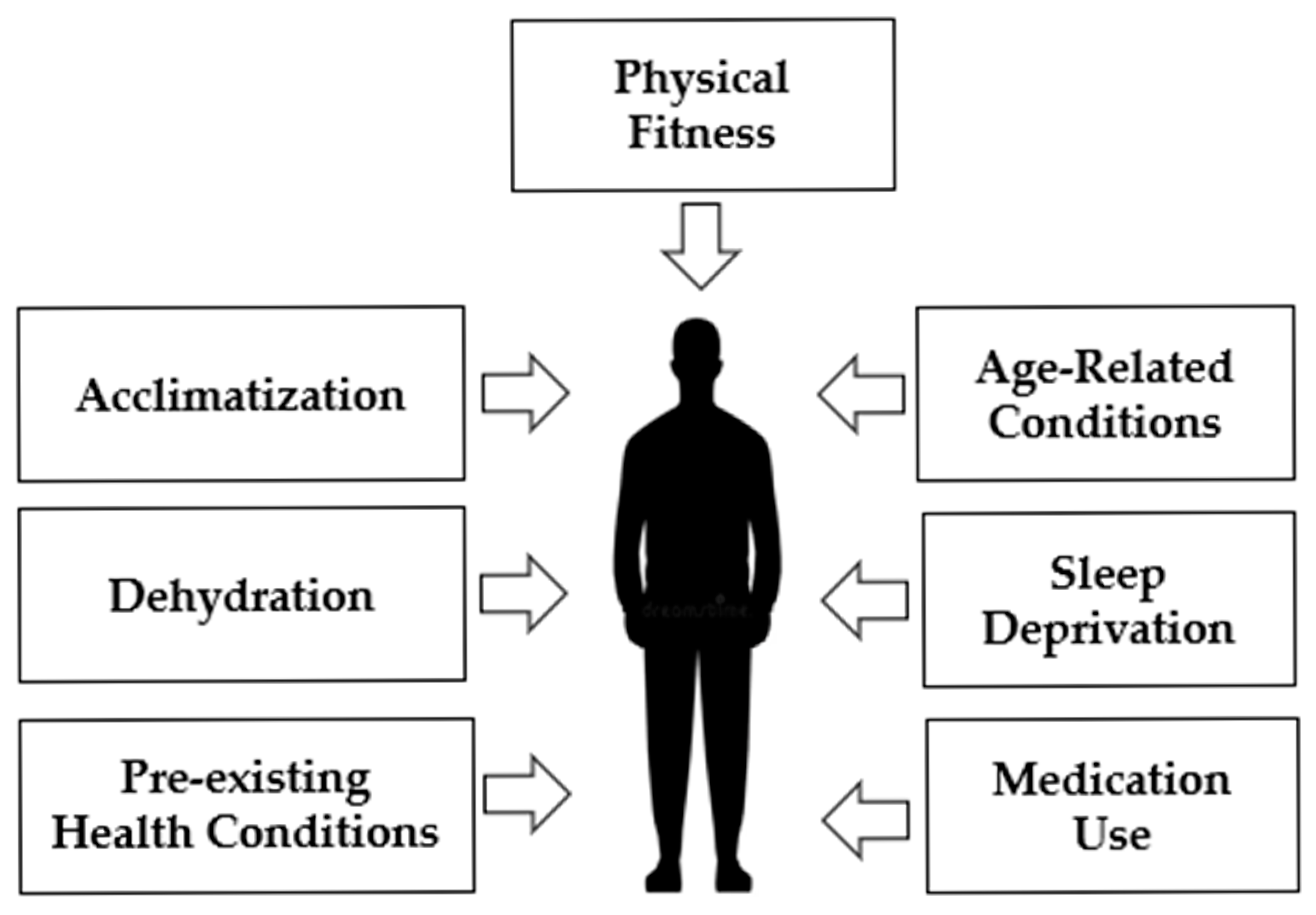

5. Personal Factors

6. Exposure Management

6.1. Heat Acclimatization

6.2. Cooling Strategies

6.3. Clinical Symptoms

7. Training

8. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruby, B.C.; Shriver, T.C.; Zderic, T.W.; Sharkey, B.J.; Burks, C.; Tysk, S. Total energy expenditure during arduous wildfire suppression. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sol, J.A.; Ruby, B.C.; Gaskill, S.E.; Dumke, C.L.; Domitrovich, J.W. Metabolic Demand of Hiking in Wildland Firefighting. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2018, 29, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Exposure to Heat and Hot Environments; DHHS (NIOSH) UBLICATION NUMBER 2016-106; NIOSH: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy, J.S.; Sol, J.A.; Hailes, W.S.; Ruby, B.C. Work patterns dictate energy demands and thermal strain during wildland firefighting. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2015, 26, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG). Incident Response Pocket Guide (IRPG); PMS 461; NWCG: Boise, ID, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Marroyo, J.A.; Molina-Terrén, D.M. Perceptions of Heat Stress, Heat Strain and Mitigation Practices in Wildfire Suppression across Southern Europe and Latin America. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Williams, A.P. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11770–11775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- USGCRP. Fourth National Climate Assessment; USGCRP: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Marvin, G.; Schram, B.; Orr, R.; Canetti, E.F.D. Occupation-Induced Fatigue and Impacts on Emergency First Responders: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). Standard on the Rehabilitation Process for Members During Emergency Operations and Training Exercises; NFPA: Quincy, MA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.nfpa.org/codes-and-standards/nfpa-1584-standard-development/1584 (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Parsons, K. Human Heat Stress, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSHA Heat Stress Recognition. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/heat-exposure/hazards (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Sawka, M.N.; Leon, L.R.; Montain, S.J.; Sonna, L.A. Integrated physiological mechanisms of heat stress. Compr. Physiol. 2011, 1, 1883–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchama, A.; Knochel, J.P. Heat stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1978–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raines, J.; Snow, R.; Petersen, A.; Harvey, J.; Nichols, D.; Aisbett, B. Pre-shift fluid intake: Effect on physiology, work and drinking during emergency wildfire fighting. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, L.G.; Tsoutsoubi, L.; Mantzios, K.; Gkikas, G.; Piil, J.F.; Dinas, P.C.; Notley, S.R.; Kenny, G.P.; Nybo, L.; Flouris, A.D. The Impacts of Sun Exposure on Worker Physiology and Cognition: Multi-Country Evidence and Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Navarro, K.M.; Fent, K.; Mayer, A.C.; Brueck, S.E.; Toennis, C.; Law, B.; Meadows, J.; Sammons, D.; Brown, S. Characterization of inhalation exposures at a wildfire incident during the Wildland Firefighter Exposure and Health Effects (WFFEHE) Study. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2023, 67, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunneley, S.A. Heat stress in protective clothing. Interactions among physical and physiological factors. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1989, 15, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lei, Z. Review of the study of relation between the thermal protection performance and the thermal comfort performance of firefighters’ clothing. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2022, 17, 15589250211068032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looney, D.P.; Lavoie, E.M.; Notley, S.R.; Holden, L.D.; Arcidiacono, D.M.; Potter, A.W.; Silder, A.; Pasiakos, S.M.; Arellano, C.J.; Karis, A.J.; et al. Metabolic Costs of Walking with Weighted Vests. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2024, 56, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, S.S.; McLellan, T.M. Heat acclimation, aerobic fitness, and hydration effects on tolerance during uncompensable heat stress. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 84, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheuvront, S.N.; Kenefick, R.W. Dehydration: Physiology, assessment, and performance effects. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, N.A. Human heat adaptation. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 325–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, J.A.; Mallis, M.M.; Caldwell, J.L.; Paul, M.A.; Miller, J.C.; Neri, D.F.; Aerospace Medical Association Fatigue Countermeasures Subcommittee of the Aerospace Human Factors Committee. Fatigue countermeasures in aviation. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2009, 80, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.; Maté, J.; Brearley, M.B.; Watson, G.; Nosaka, K.; Laursen, P.B. Ice slurry ingestion increases core temperature capacity and running time in the heat. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RT-130, Wildland Fire Safety Training Annual Refresher (WFSTAR), National Wildfire Coordination Group. Available online: https://www.nwcg.gov/training-courses/rt-130 (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- US Department of Agriculture, US Forest Service, MTDC. Heat Illness Basics for Wildland Firefighters. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/t-d/pubs/pdfpubs/pdf10512316/pdf10512316dpi72.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- National Wildfire Coordination Group. Heat Illness Prevention Pocket Guide. Available online: https://www.hprc-online.org/resources-partners/whec/educational-tools/heat-illness (accessed on 27 January 2026).

| Work Intensity | Activity Description | Metabolic Heat Production |

|---|---|---|

| Resting | Sitting, eating, talking | 100–110 W |

| Light | Walking and standing | 180–200 W |

| Moderate | Moving with protective gear | 300–350 W |

| Heavy | Shoveling, carrying loads | 400–600 W |

| Severe | Climbing, cutting timber | +1000 W |

| Intervention | Management |

|---|---|

| Work Intensity | Reducing workloads under high-temperature conditions |

| Timing | Performing work during cooler periods of the day |

| Rest Breaks | Implementing regular breaks in shaded areas |

| Clothing | Minimizing use of multiple layers to maximize ventilation |

| Hydration | Consuming small amounts of water often |

| Acclimatization | Increasing workload gradually over a two-week period |

| Buddy System | Monitoring partners for heat illness signs |

| Heat Illness | Symptoms | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Heat Cramp | Heavy sweating | 1. Provide rest |

| Painful muscle cramps | 2. Move to a cooler location | |

| 3. Provide water or juice | ||

| Heat Exhaustion | Heavy sweating | 1. Provide rest |

| Weakness, fatigue | 2. Loosen clothing | |

| Headache, dizziness | 3. Provide water or juice | |

| Vomiting, fainting | 4. Saturate clothing with water | |

| Heat Stroke | Lack of sweating | 1. Medical emergency |

| Headache | 2. Evacuate to clinical facility | |

| Confusion | 3. Saturate clothing with water | |

| Dizziness, vomiting | 4. Immerse body in cool water | |

| Hot and dry skin | ||

| Loss of consciousness |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Reischl, U. Wildland Firefighter Heat Stress Management. Fire 2026, 9, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire9020068

Reischl U. Wildland Firefighter Heat Stress Management. Fire. 2026; 9(2):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire9020068

Chicago/Turabian StyleReischl, Uwe. 2026. "Wildland Firefighter Heat Stress Management" Fire 9, no. 2: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire9020068

APA StyleReischl, U. (2026). Wildland Firefighter Heat Stress Management. Fire, 9(2), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire9020068