Cascading Impacts of Wildfire Emissions on Air Quality, Human Health, and Climate Change Based on Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Global Challenge of Increasing Wildfire Occurrence

1.2. Atmospheric Pollution and Public Health Crises

1.3. Research Gaps

1.4. Study Objectives and Novelty

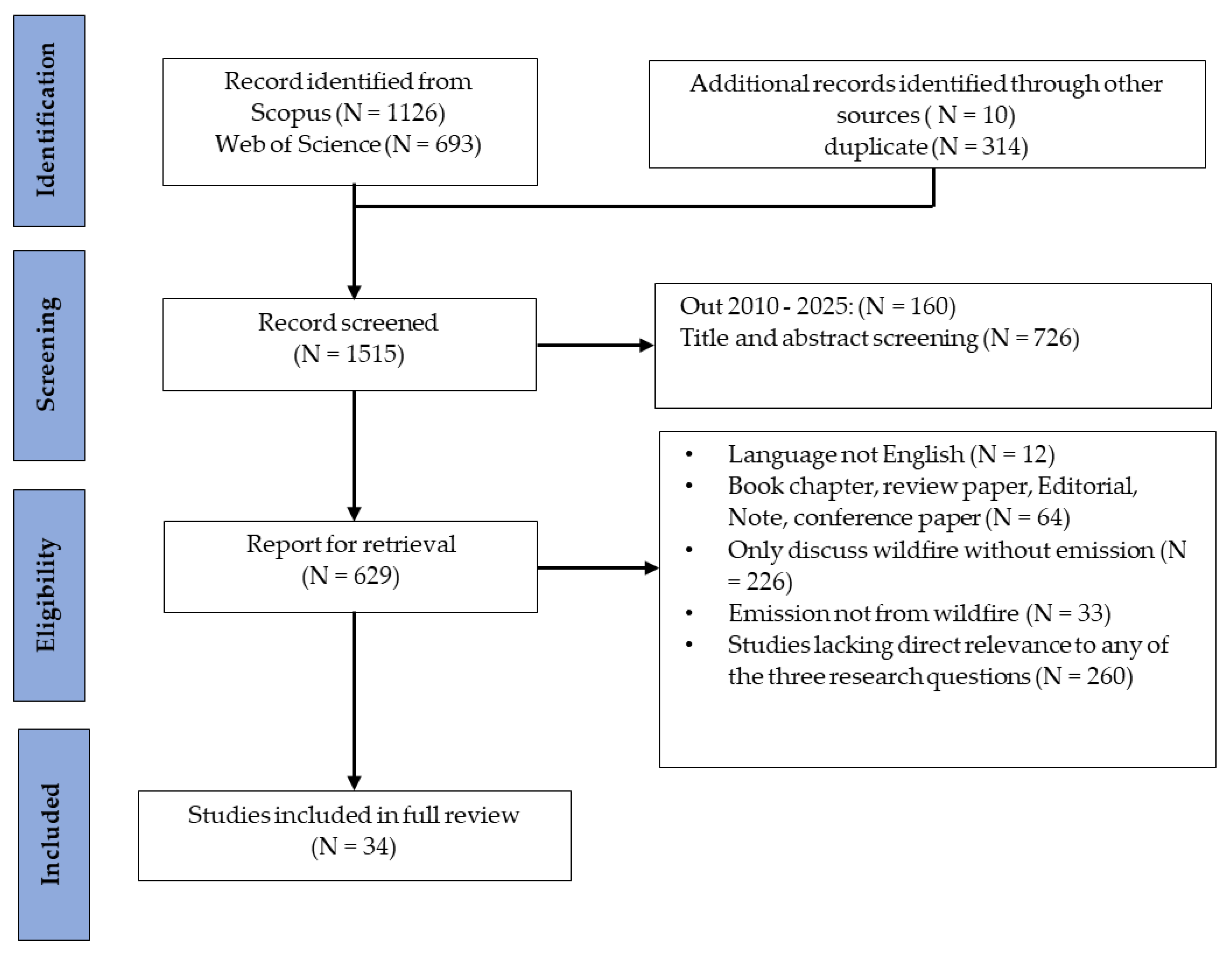

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Selection Criteria

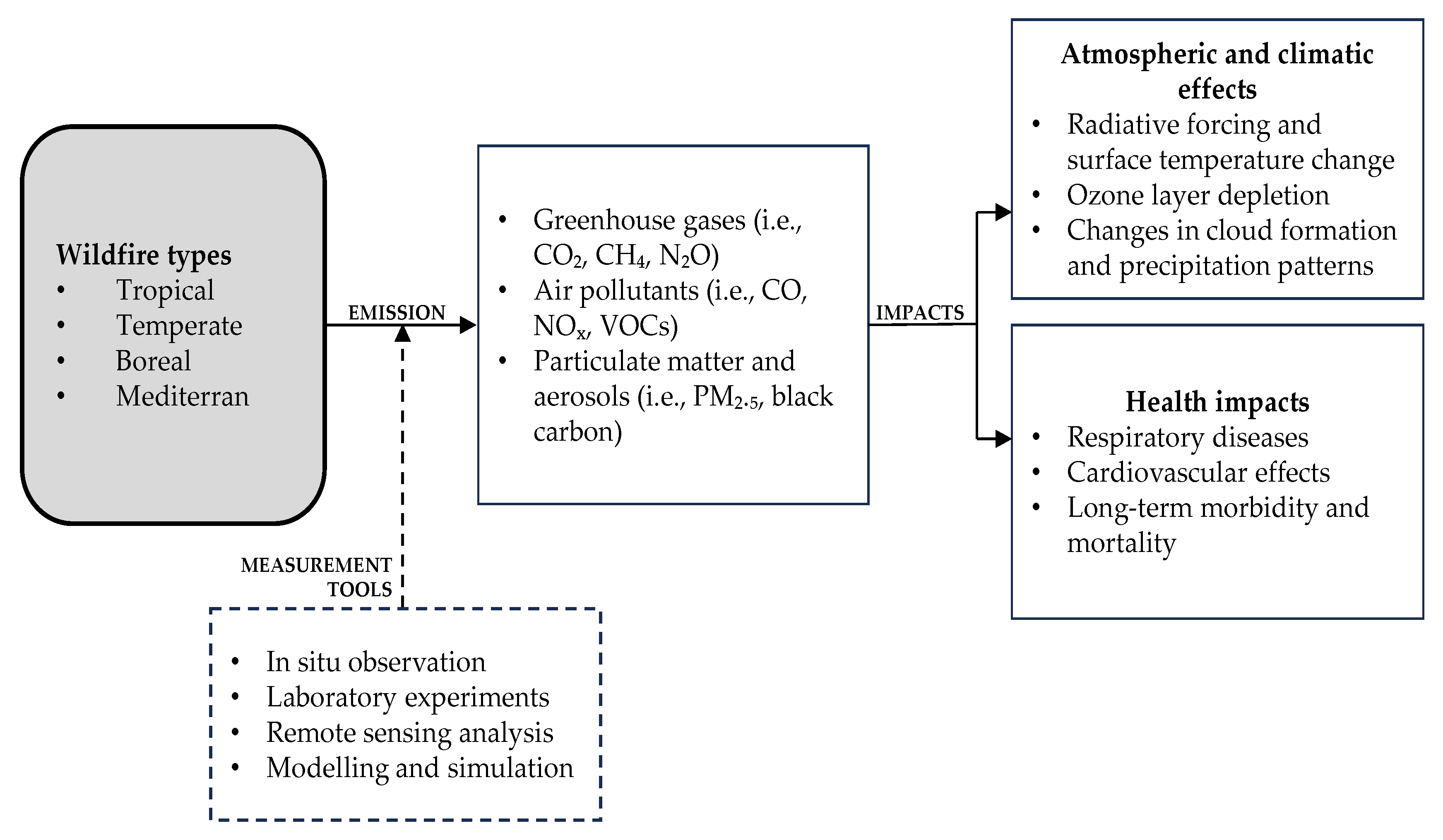

2.3. Analytical Framework

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overview of Selected Literature

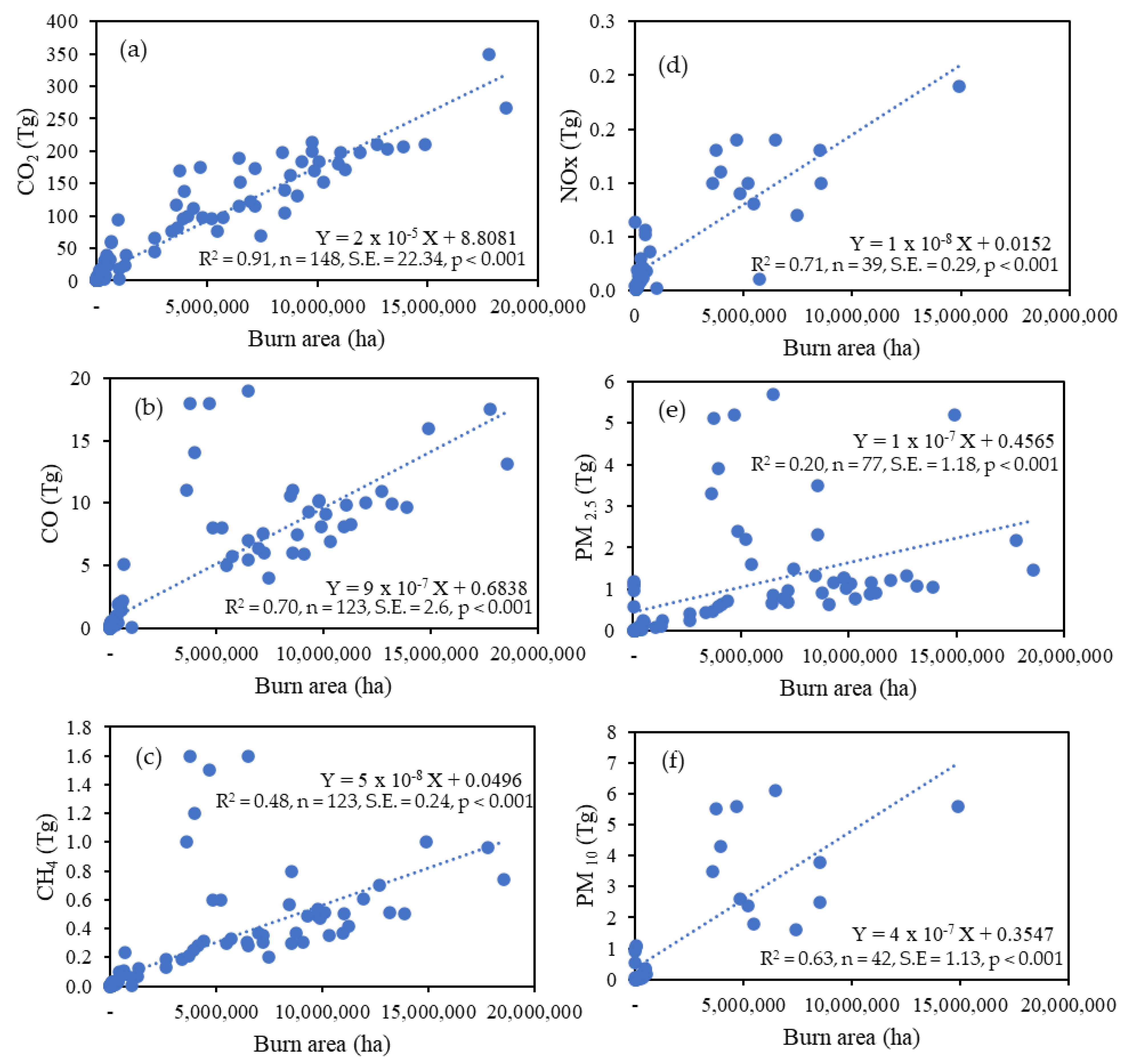

3.2. Magnitude and Composition of Emissions

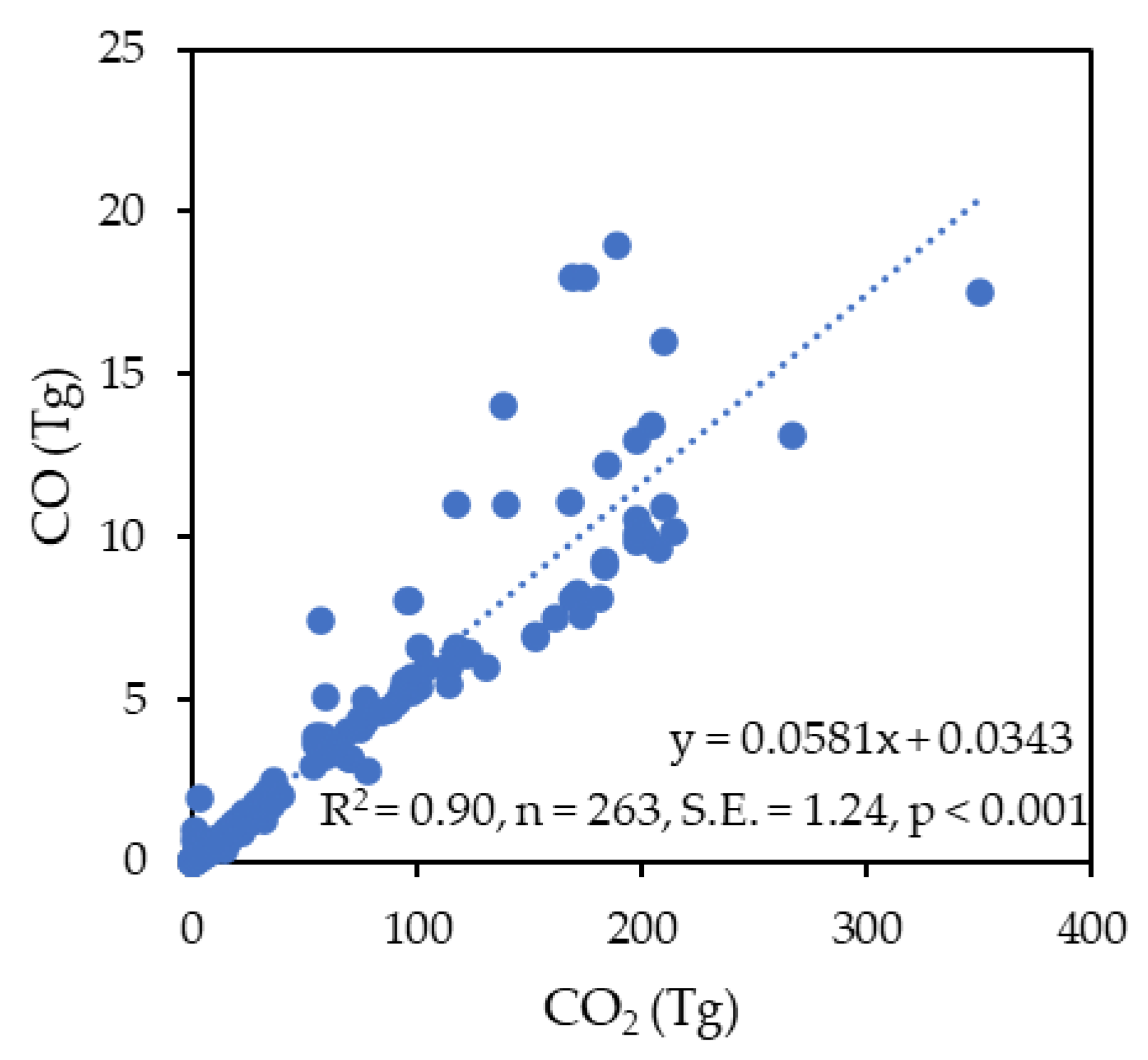

3.2.1. Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

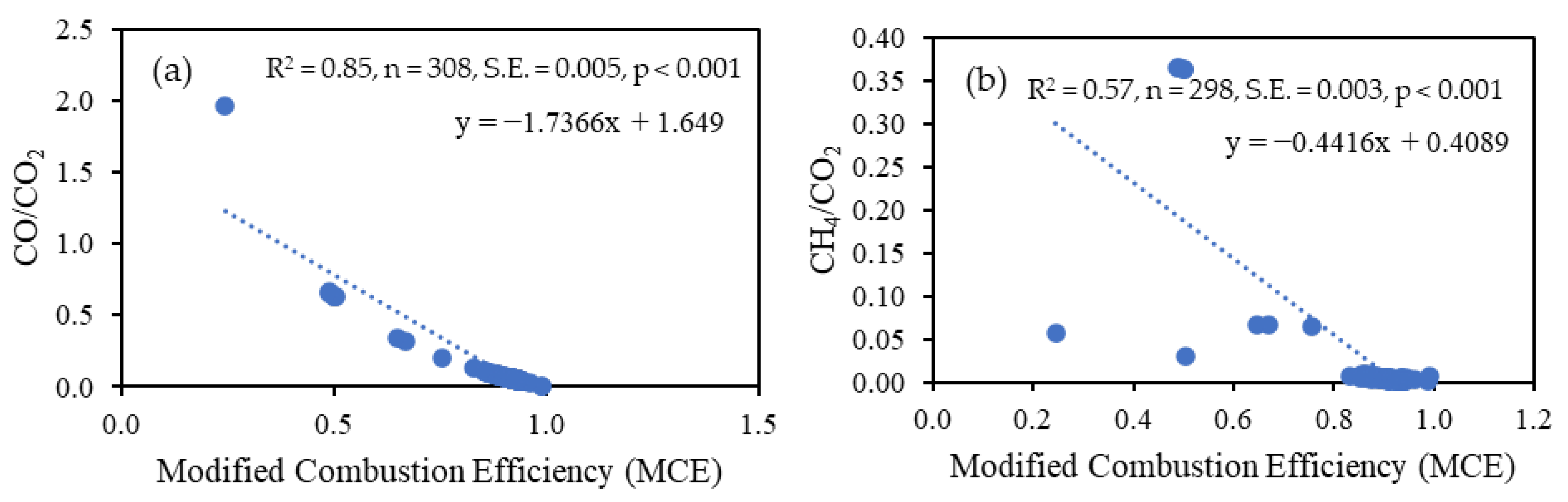

3.2.2. Carbon Monoxide (CO)

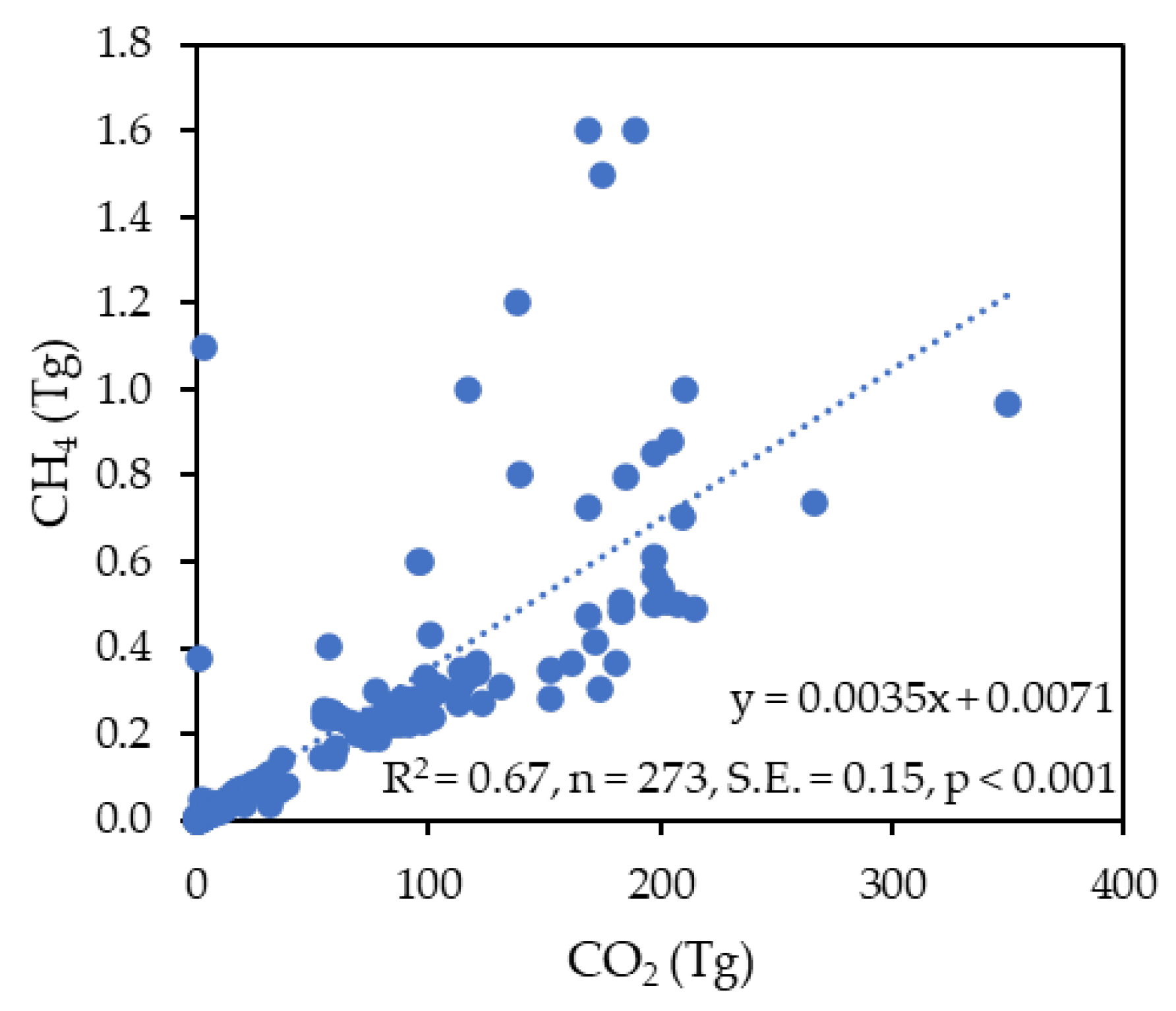

3.2.3. Methane (CH4)

3.2.4. Nitrogen Oxides (NOx)

3.2.5. Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10)

3.3. Atmospheric Chemistry and Ozone Layer Effects

3.3.1. Tropospheric Ozone Formation

3.3.2. Stratospheric Ozone Perturbation

| References | Location | Year | Injection Height (km) | Stratospheric Aerosol Mass (Tg) | Duration of Perturbation (month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peterson et al. [119] | Australia | 2019–2020 | 30.0–35.0 | 0.3–1.1 | >3 |

| Rieger et al. [126] | Australia | 2020 | 20.0–25.0 | - | 6–9 |

| Khaykin et al. [120] | Australia | 2019–2020 | Up to 35.0 | 0.4–0.6 | >3 |

| Damany-Pearce et al. [121] | Southern midlatitudes | 2020 | 25.0–35.0 | 0.8 | 5–6 |

| Khaykin et al. [125] | Canada | 2019–2020 | 10.9–16.5 | 0.03–0.06 | 6 |

| Torres et al. [122] | British Columbia PyroCb, Canada | 2017 | 12.0–14.0 | 0.18–0.35 | 8–10 |

| Das et al. [123] | British Columbia PyroCb, Canada | 2017 | 12.0–23.0 | 0.3 | 5 |

| Ohneiser et al. [124] | Chile | 2020 | 19.0–20.0 | up to 0.85 | >12 |

3.4. Impact of Wildfire on Climate Change

3.5. Public Health Impacts

| References | Location | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Wen et al. [134] | New South Wales, Australia | Higher health risk in low socioeconomic status and high fire-density areas. |

| Pongpiachan et al. [135] | Northern Thailand | Minor role of PAHs from biomass burning in local health effects |

| Tarín-Carrasco et al. [100] | Portugal | 35% increase in respiratory mortality during fire years. |

| Barbosa et al. [137] | Portugal | High wildfire emissions in 2017 coincided with increased mortality and economic loss. |

| Schroeder et al. [138] | Brazil | Strong Spearman correlation (r = 0.66) between fire events and respiratory death. |

| Pye et al. [135] | Western USA | Emissions: 1250 g ROC/kg CO; particulate phase drives health burden. |

| Maji et al. [136] | Southeastern USA (10 states) | PM2.5 increased by 10% (prescribed) and 22% (extensive burns); mortality linked. |

4. Overall Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The findings demonstrate that carbon dioxide (CO2) dominates total fire-related emissions and shows strong predictive correlations with carbon monoxide (CO) and methane (CH4), highlighting their interdependence under varying combustion regimes. The Modified Combustion Efficiency (MCE) is identified as a key determinant of emission composition, with higher MCE values yielding complete combustion and higher CO2 outputs, whereas lower MCE values increase incomplete combustion products such as CO, CH4, and particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10).

- These emissions exert measurable influences on both regional and global climate systems. Fire-related GHGs and aerosols intensify radiative forcing, increase near-surface air temperatures, and promote the formation of tropospheric and stratospheric ozone, collectively amplifying feedback mechanisms that accelerate global warming and elevate future fire risks. At the atmospheric–biospheric interface, the deposition of black carbon and aerosols reduces albedo, contributing further to localized warming and altering carbon cycle dynamics. Beyond climate implications, fire emissions substantially deteriorate air quality and human health. Exposure to fine particulates and ozone is consistently associated with increased respiratory and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, highlighting the intersection between ecological disturbance and public health crises.

- Despite notable advances, methodological inconsistencies remain a key limitation across studies. Disparities in emission factor selection, satellite detection capability, and ecosystem representation contribute to significant uncertainty in global emission inventories. Cross-ecosystem analyses, particularly involving peat, tropical, and boreal fires, remain underrepresented. To address these gaps, future research should prioritize harmonization of emission measurement techniques, the integration of high-resolution remote sensing with in situ validation, and the expansion of standardized emission factor databases across biomes.

- Interdisciplinary frameworks linking atmospheric science, ecology, and epidemiology are essential to refine emission modeling, strengthen climate projections, and guide evidence-based mitigation and adaptation policies. Moreover, this review advances scientific understanding of the coupled nature of combustion efficiency, emission variability, and climate feedback, while providing a foundation for more reliable global emission inventories and informed policy interventions in fire-prone ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AWiFS | Advanced Wide Field Sensor |

| CHIMERE | CHIMERE Atmospheric Chemistry-Transport Model |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| FINN | Fire INventory from NCAR |

| GABAM | Global Anthropogenic Biomass Burning Emissions Model |

| GFED | Global Fire Emissions Database |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| HKH | Hindu Kush Himalaya |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| LAS SAF | Land Surface Analysis Satellite Applications Facility |

| NCAR | National Center for Atmospheric Research |

| NEI | National Emissions Inventory |

| NPP | National Polar-orbiting Partnership (Suomi NPP satellite) |

| NRSC | National Remote Sensing Centre |

| SEVIRI | Spinning Enhanced Visible and Infrared Imager |

| TIER 3 | Highest methodological level for emission estimation using detailed country-specific data and advanced models. |

| VIIRS | Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite |

| WF_ABBA | Wildfire Automated Biomass Burning Algorithm |

| WRF/CMAQ | Weather Research and Forecasting/Community Multiscale Air Quality model |

Appendix A

| Reference | Region | Methodology & Data | Key Findings | Main Impact | Primary Uncertainty Sources | Dominant Forest Type/Land Cover | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al. [39] | China | Combined MCD64A1 and MCD14ML to improve detection of small fires. | Crop residue burning was the largest source. A clear trend of increasing emissions from forest/shrubland fires (2003–2015). | Vital for modeling severe haze events in populated regions of China, linking fire activity to human exposure to extreme PM2.5. | Under-detection of small fires by MCD64A1. | Agricultural lands, Forest, Shrubland | Blend active fire and burned area products to create a more complete fire inventory. |

| Qiu et al. [36] | China | High-res inventory using MODIS (MCD64A1) BA & active fires (MCD14ML) with detailed land cover. | Crop residue burning was dominant (>50% of emissions). Peaks in June and October linked to agricultural cycles. | Critical for crafting targeted air pollution policies in China, directly linking emissions to specific agricultural practices. | Detection of small, agricultural fires. | Agricultural lands | Integrate data from multiple satellites and ground reports to improve detection in agricultural regions. |

| Shi et al. [41] | China | Used MCD64A1 BA, MODIS FRP, and active fire data (MCD14ML) for NEC. | Average annual emissions (2001–2017): e.g., CO2 (30,816.8 Gg), PM2.5 (225.3 Gg). Forest fires in Inner Mongolia and Heilongjiang explained variations. | Provides a high-resolution, multi-year inventory crucial for understanding regional carbon cycling and air pollution control. | Fuel load assessment and combustion efficiency in northeastern forests. | Temperate forest, Grasslands | Improve spatial resolution of biomass data and validate emission factors for regional applications. |

| Yin et al. [45] | China | Used MODIS Fire Radiative Energy (FRE) data and GlobeLand30 land cover. | Average annual emissions (2003–2017): e.g., CO2 (91.4 Tg), PM2.5 (0.51 Tg). Forest fires were the primary source (45% of CO2). | Demonstrates the significant role of biomass burning and provides an alternative FRE-based methodology for emission estimation. | FRE-to-emissions conversion factors. | Temperate Forest, Grasslands | Develop and validate region-specific conversion coefficients for different biomes. |

| Zhang et al. [47] | China | Used MODIS fire and BA products with NPP (MOD17A3) data. | Southwest forests showed net carbon loss, while Northeast forests showed resilience (increased NPP post-fire). | Reveals divergent regional responses to fire, highlighting the importance of a net carbon budget perspective. | Carbon cycle dynamics post-fire and NPP estimation accuracy. | Mixed forests (SW), Temperate forests (NE) | Integrate carbon emission and sequestration assessments for a net carbon budget perspective. |

| Song et al. [38] | China | Used MODIS BA data (2003–2015) and a bottom-up approach. | Annual average emissions: ~130 Tg CO2. Highest emissions in Yunnan, Sichuan, Inner Mongolia. Peaks in spring and autumn. | Provides a comprehensive national-scale assessment essential for understanding contribution to regional air pollution. | Emission factors for Chinese forests and fire detection accuracy. | Mixed forest | Develop a national-specific emission factor database and improve fire monitoring capabilities. |

| Ye et al. [48] | China | Combined Sentinel-2 and field data to quantify burning and suppression emissions. | 16.5% of total GHG emissions came from suppression activities (10,498.30 t CO2e). Helicopter transport was a major contributor. | Introduces a novel, holistic perspective on the carbon cost of fire management, suggesting suppression efforts have a non-negligible climate impact. | Emissions from emergency response infrastructure are currently overlooked. | Evergreen forest | Develop a comprehensive accounting framework that includes both fire and suppression emissions. |

| Wu et al. [46] | China | Used MODIS (MCD64A1 and MCD14ML) data to track moving high emissions from biomass burning (2003–2014). | Emissions from heating season decreased while corn harvest season emissions increased. | Reveals shifting patterns of biomass burning in China linked to changes in agricultural practices and energy use. | Tracking the movement of emission hotspots over time. | Agricultural lands, Forests | Develop dynamic emission inventory methods that can capture spatial-temporal changes in burning patterns. |

| Li et al. [49] | China | Used FireCCI51 BA and a 1km aboveground biomass dataset for temperate forests. | Estimated multi-year emissions for Heilongjiang. Forest fires occurred mainly in autumn (62.78%) and spring (36.24%). | Provides a detailed inventory essential for atmospheric transport models and supports pollution control strategies in temperate regions. | Biomass fuel loading estimates and combustion efficiency in temperate forests. | Temperate forest | Improve spatial resolution of fuel load data and validate consumption models for temperate regions. |

| Wang et al. [50] | China | Land cover MODIS (MCD12Q1 v006), Burned Area data (MCD64A1 v006). | Forest fire emissions peaked in spring and winter. | Impact on local air quality and the global climate | Forest fire emission uncertainties stem from burned area, biomass density, burning efficiency, and emission factors | Mixed forest, Broad-leaf forest, Needle-leaf forest | Development of high-resolution regional forest fire emission inventories |

| Yang and Jiang [51] | China | GABAM dataset for burned area by the Chinese Academy of Science. | CO2 dominated emissions (2.25 × 104 Gg, 92.5%), followed by CO (1.13 × 103 Gg), PM10 (200.5 Gg), and PM2.5 (140.3 Gg) | Influence of fire on the local environment and policy on China’s air pollution control | This method only includes forests, shrublands, and grasslands, potentially underestimating total fire emissions | Evergreen forest | New large-scale CE methods are needed to reduce fire emission uncertainties. |

| Kayet et al. [56] | India | 1 × 1 km gridded inventory using MODIS MCD45A1 BA and NRSC land cover. | Estimated annual average emissions for Karnataka (2000–2022), e.g., SO2 (6.67 Gg), NOx (9.48 Gg), NH3 (9.80 Gg), CO (670.12 Gg), OC (59.78 Gg), BC (5.09 Gg). | Provides a high-resolution inventory crucial for local air quality assessment, health impact studies, and targeted mitigation strategies. | Spatial allocation of emissions and fuel load estimates. | Tropical forests, Agricultural lands | Use numerical simulation models integrating climate parameters and high-resolution temporal data. |

| Reddy et al. [57] | India | Mapped burned area using high-resolution (56m) Resourcesat-2 AWiFS data. Long-term trends from MODIS active fires | 17% of national CO2 emissions originated from Protected Areas (PAs). Dry deciduous forests contributed the most. | Sounds an alarm for biodiversity conservation, showing PAs are highly vulnerable to fires, leading to significant carbon losses. | Biomass data and combustion completeness for diverse Indian forests. | Dry Deciduous forest, Protected areas | Use high-resolution satellites (e.g., AWiFS) to monitor ecologically sensitive areas. |

| Saranya et al. [58] | India | Forest fire analysis AWiFS and LISSIII datasets | The mean annual carbon emission rate was 1.26 Tg CO2/yr | Rising CO2 levels negatively affect human health | - | semi-evergreen | Strategic plan control forest fires |

| Bartowitz et al. [55] | United States | Fire severity and area burned from the Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity database | Harvesting mature trees to prevent fire increases emissions instead of reducing them | Site-specific forest management that balances short-term protection with long-term carbon preservation is vital for mitigating climate change | Uncertainties for contemporary forest fire emissions | Temperate and Mediterranean forests | Prescribed burns reduce fire risk |

| Larkin et al. [34] | United States | Comparative analysis of four inventories (GFED, FINN, NEI+, EPA GHG). | Inventories varied by a factor of 10 (e.g., CO2e). NEI+ showed highest totals; GFED the lowest. Disagreement in seasonal peaks. | Highlights critical uncertainties in US emission reporting, affecting air quality management, climate policy, and carbon accounting. | Fire area detection (small/prescribed fires), fuel loading databases, modeling of deep organic soil combustion. | Boreal, Temperate, Grasslands | Standardize detection methods and improve dynamic fuel mapping. |

| Carvalho et al. [44] | Portugal | Used CHIMERE model with future area burned projections under IPCC SRES A2. | Projected increases in fires will lead to higher O3 and PM10 concentrations, potentially offsetting gains from emission controls. | Provides a forward-looking perspective that climate-induced fire increases may severely hamper future air quality improvements. | Projecting future fire activity and its interaction with changing atmospheric chemistry. | Mediterranean forest | Integrate dynamic fire-emission modules within climate-air quality modeling frameworks. |

| Martins et al. [63] | Portugal | Burnt area from the National Forest Fires Inventory | summer condition contribution to the higher measured PM10 values | Forest fire impacts on PM10 and ozone | - | Mediterranean forest | Forest fire emissions should be included in summer air quality models |

| Permadi & Oanh [40] | Indonesia | MODIS MCD45A1 BA & GlobCover land cover. Region-specific EFs and GWP. | Peatland and forest fires contributed 85–90% of emissions. BC was the 3rd most important warming agent (12–21% of forcing). | Reveals the disproportionate climate impact of peat fires, emphasizing the need to include short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) in mitigation. | Peat combustion depth and emissions factors. | Tropical peatland, Secondary forest | Develop specialized algorithms for detecting smoldering peat fires and improve peat-specific EFs. |

| Junpen et al. [37] | Thailand | Utilized MODIS active fire data and conducted prescribed burning experiments for EFs. | 27,817 fire hotspots detected (2005–2009), peaking in March. Total burned area: 159,309 ha. | Confirms forest fires as a major source of atmospheric pollutants in Thailand, providing critical data for regional air quality management. | Emission factors and detection of small fires. | Tropical forest | Use country-specific emission factors and improve detection of understory fires. |

| Bondur et al. [42] | Russia | Long-term (2001–2023) analysis using MODIS (MCD64A1)BA & land cover (MCD12Q1). | Record high burned area in 2021 (~91,800 km2). A rising FRP trend linked to climate change. The Far East is a disproportionate hotspot. | Quantifies massive carbon emissions from Russian wildfires, underscoring their growing impact on the global carbon cycle. | Scaling emissions from boreal forests with high fuel loads. | Boreal forest (Taiga) | Develop and employ biome-specific emission factors and fuel consumption models for boreal regions. |

| Baldassarre et al. [43] | Turkey | Evaluated geostationary (SEVIRI) vs. polar-orbiting (MODIS) FRP. WRF/CMAQ simulations. | 15 min data captured diurnal cycle and peak intensity missed by MODIS. LSA SAF emissions showed superior plume agreement. | Demonstrates the paramount importance of high-temporal-resolution data for accurate air quality forecasting and public health warnings. | Algorithm choice for FRP retrieval (WF_ABBA vs. LSA SAF). Temporal and vertical allocation of emissions. | Mediterranean forest | Prioritize high-temporal-resolution geostationary data for emission modeling. |

| Bhujel et al. [52] | Nepal | burnt-area product (MCD45A1), and Field survey | Annually, over 3158 ha of forest burns, emitting ~1108 t C (≈4066 t CO2, 2581 t CO, 1474 t CH4) | - | - | Tropical forest, Hill sall forest, Riverine forest | Forest management should combine fire lines, conservation ponds, and community capacity building |

| Bertolin et al. [64] | Argentina | Field study and laboratories. Burn area from Fire Program, Subsecretaría de Bosques de la Provincia de Chubut | C losses from fires were 104.6, 90.7, and 94.7 Mg C/ha across the three sites | Negative carbon balance for all three locations due to no carbon sequestration. | - | Mediterranean forests | Future work should ensure continued carbon capture, reduce disturbance losses, manage old-growth forests, and conserve forest diversity and connectivity |

| Scarpa et al. [65] | Italy | Fire activity data from Italian Forest Service and Satellite data for land use | Italy’s average GHG and particulate emissions were 2621 Gg/yr, ranging from 772 Gg in 2013 to 7020 Gg in 2007. | Essential for air quality management, mitigating wildfire impacts, and guiding prescribed fire decisions | Uncertainties in emission estimates | Mediterranean forests | Thoroughly assess the model and compare with field data. |

| Teixeira et al. [59] | Brazil | Temporal and spatial analysis of fire spot and biomass burning. Fire Inventory (FINN) model version 1.5, from the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) | Most fire events occurred in natural forests (37%), with croplands/pastures (29%) and grasslands (19%) representing the next most affected land types. | Provide information for tackling climate and health issues related to air quality | Uncertain class, which can be either agricultural or pasture areas. | Tropical and subtropical Atlantic forest | Future studies should integrate land use, human activities, and meteorology to better understand fire drivers and emissions |

| Bilgiç et al. [66] | Greece | Sentinel-2 imagery calculated normalized burn rate difference index (dNBR), while CORINE land cover data found burned area land cover | The largest burned areas (~50,000 ha) occurred in western Türkiye and central Greece | FINN and GFED databases mostly underestimated emissions | uncertainties in the fuel load and combustion completeness parameters | Mediterranean forests | Sentinel-2–based method for emission calculations. |

| Korísteková et al. [53] | Slovakia | Used a Tiered approach to estimate GHG emissions from forest fires. | The share of GHG emissions from forest fires is less than 1% of national totals. TIER 1 underestimated compared to TIER 2/3. | Highlights the small but non-negligible contribution of forest fires to national GHG budgets, emphasizing the need for accurate accounting. | Biomass available for burning and combustion factors. | Temperate mountain forest | Use more complex methods (TIER 3) for GHG emission determination, especially for larger fires. |

| Bar et al. [54] | Himalaya | Used MODIS MCD64A1, land cover, and biomass data over 20 years. | Eastern Himalayas (India) were the largest emission source (20.37 Tg CO2). Emissions showed high interannual variability. | Addresses a critical data gap, linking fire emissions to glacial melting (Via BC deposition) and threatening water security. | Complex terrain causing satellite detection errors; poorly constrained mountain forest biomass. | Mountain forests | Apply terrain corrections to satellite data and develop region-specific biomass maps for mountain ecosystems. |

| Shi & Yamaguchi [35] | Southeast Asia | Bottom-up inventory using MODIS burned area (MCD64A1) and active fire products (MOD14/MYD14). | Quantified significant annual emissions (55,388 Gg CO, 817,809 Gg CO2). Major peak in Jan-Mar (dry season). | Provides a foundational emission dataset for modeling transboundary haze pollution and its impacts on regional air quality and public health. | Relies on accuracy of MODIS burned area detection and regional average EFs. | Tropical forest, Peatlands, Agriculture | Incorporate higher-resolution data and region-specific EFs to reduce uncertainty, especially for peatlands. |

| Aditi et al. [60] | South Asia | Used Suomi-NPP VIIRS and MCD12Q1 land cover to develop an inventory. | Estimated annual emissions: 91.58 Tg CO2, 0.60 Tg PM2.5. Major emissions from forest fires in the HKH and Central Highlands. | Establishes forest fire as a major sector of GHG and aerosol emissions in South Asia, essential for regional climate models. | Emission factors for diverse South Asian forests. | Tropical, Subtropical, Temperate forest | Utilize VIIRS data for improved fire detection and develop region-specific emission inventories. |

| Chang & Song [61] | Tropical Asia | Compared two satellite BA products (L3JRC and MCD45A1) to estimate emissions. | Indonesia and India were largest contributors. MCD45A1 generally yielded lower estimates than L3JRC. Two emission peaks were identified: Feb-Mar (forest fires) and Aug-Oct (peat fires) | Highlights the sensitivity of regional emission budgets to input data selection, affecting haze prediction accuracy. | Choice of satellite burned area product (L3JRC vs. MCD45A1). | Tropical forest, Peatlands | Fuse multiple burned area products to create a consensus dataset with uncertainty bounds. |

| Shi et al. [62] | Tropical continents (Americas, Africa, Asia) | MODIS MCD64A1 burned area product Fire Radiative Power (FRP) and Fire Radiative Energy (FRE) | Average annual CO2 emissions: 6083.69 Tg/yr Major contributors: woody savanna/shrubland (52%), savanna/grassland (27%), forest (17%), cropland (3%), peatland (1%) Africa is the largest emitter (62%), followed by Asia (20%) and the Americas (18%) Peak emissions during August–September | Identifies spatial-temporal emission dynamics by land type and continent | Burned area detection limitations (small fires missed by MODIS) Uncertainty in AGB (~50%) and CE (20–30%) Emission factor variability by biome FRE conversion ratio error (~10–31%) Incomplete detection of small agricultural fires | Woody savanna/shrubland (Africa) Savanna/grassland (Americas) Forest (Asia) Minor: peatland (SE Asia), cropland (India, SE Asia) | Integrate small fire detection (using VIIRS or higher-resolution sensors) Improve AGB and CE estimation using ground validation Link emissions inventory with air quality and health models |

| Huang et al. [67] | Alaska | Conducted In Situ aircraft measurements during interior Alaska fires. | CO2 and CH4 concentrations were significantly higher near flaming fronts. BC deposition enhanced local radiative forcing. | Provides rare empirical data on immediate GHG and aerosol concentrations within plumes, crucial for validating models. | Spatial heterogeneity of plume composition and radiative effects. | Boreal forest | Conduct more in situ measurements to validate model simulations and improve RF calculations. |

| Lamarque et al. [32] | Global | Historical reconstruction (1850–2000) of anthropogenic and BB emissions. | Model simulations indicated underestimation of CO concentrations, particularly in the Northern Hemisphere. | Provides a foundational historical emission dataset for modeling long-term atmospheric composition changes. | Historical data accuracy and emission factor consistency over time. | Global | Improve historical emission constraints using multiple data sources and model validation. |

| Mieville et al. [33] | Global | Historical reconstruction using satellite products (GBA2000 burnt areas, ATSR fire hotspots) and historical data. | Global emissions stable until 1970s (~7400 Tg CO2/yr), then increased to ~9950 Tg CO2/yr. Boreal/temperate fires decreased due to suppression. | Provides a century-scale perspective on global fire emissions, highlighting the impact of human management practices. | Historical data reliability and scaling of emissions over time. | Global (Forest, Savanna) | Improve historical biomass burning reconstructions using multi-proxy data integration. |

References

- Liu, Z.; Ballantyne, A.P.; Cooper, L.A. Biophysical feedback of global forest fires on surface temperature. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, M.T.; Nordling, K.; Samset, B.H. The influence of variability on fire weather conditions in high latitude regions under present and future global warming. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 065016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.P.; Abatzoglou, J.T. Recent advances and remaining uncertainties in resolving past and future climate effects on global fire activity. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2016, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, B.M.; Neilson, R.P.; Drapek, R.; Lenihan, J.M.; Wells, J.R.; Bachelet, D.; Law, B.E. Impacts of climate change on fire regimes and carbon stocks of the U.S. Pacific Northwest. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, G03037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angra, D.; Sapountzaki, K. Climate change affecting forest fire and flood risk—Facts, predictions, and perceptions in Central and South Greece. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, E. Future climate change impact on wildfire danger over the Mediterranean: The case of Greece. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 045022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillett, N.P.; Weaver, A.J.; Zwiers, F.W.; Flannigan, M.D. Detecting the effect of climate change on Canadian forest fires. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L18211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werf, G.R.; Randerson, J.T.; Giglio, L.; Collatz, G.J.; Mu, M.; Kasibhatla, P.S.; Morton, D.C.; DeFries, R.S.; Jin, Y.; van Leeuwen, T.T. Global fire emissions and the contribution of deforestation, savanna, forest, agricultural, and peat fires (1997–2009). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 11707–11735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.; Corringham, T.; Gershunov, A.; Benmarhnia, T. Wildfire smoke impacts respiratory health more than fine particles from other sources: Observational evidence from Southern California. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, B.; Val Martin, M.; Zelasky, S.E.; Fischer, E.V.; Anenberg, S.C.; Heald, C.L.; Pierce, J.R. Future fire impacts on smoke concentrations, visibility, and health in the contiguous United States. GeoHealth 2018, 2, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Ying, Q. Modeling the impacts of open biomass burning on regional O3 and PM2.5 in Southeast Asia considering light absorption and photochemical bleaching of Brown carbon. Atmos. Environ. 2025, 342, 120942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adame, J.A.; Lope, L.; Hidalgo, P.J.; Sorribas, M.; Gutiérrez-Álvarez, I.; del Águila, A.; Lopez, A.S.; Yela, M. Study of the exceptional meteorological conditions, trace gases and particulate matter measured during the 2017 forest fire in Doñana Natural Park, Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetona, O.; Reinhardt, T.E.; Domitrovich, J.; Broyles, G.; Adetona, A.M.; Kleinman, M.T.; Ottmar, R.D.; Naeher, L.P. Review of the health effects of wildland fire smoke on wildland firefighters and the public. Inhal. Toxicol. 2016, 28, 95–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, A.; Headon, K.; Han, T.; Umer, W.; Wu, J. Associations between short-term exposure to wildfire particulate matter and respiratory outcomes: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 168134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, A.; Woods, B.; Krapfl, H.; Toth, B. Health outcomes associated with smoke exposure in Albuquerque, New Mexico, during the 2011 Wallow fire. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2015, 21, S55–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Zang, E.; Liu, Y.; Wei, J.; Lu, Y.; Krumholz, H.M.; Bell, M.L.; Chen, K. Long-term exposure to wildland fire smoke PM2.5 and mortality in the contiguous United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2024, 121, e2403960121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, E.; Runkle, J.D. Long-term health effects of wildfire exposure: A scoping review. J. Clim. Change Health 2022, 6, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilgus, M.L.; Merchant, M. Clearing the air: Understanding the impact of wildfire smoke on asthma and COPD. Healthcare 2024, 12, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Hänninen, R.; Sofiev, M.; Aunan, K. Fires as a source of annual ambient PM2.5 exposure and chronic health impacts in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Cui, L.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Song, X.; Xu, Z. Advances in the study of global forest wildfires. J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 2654–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargali, H.; Pandey, A.; Bhatt, D.; Sundriyal, R.C.; Uniyal, V.P. Forest fire management, funding dynamics, and research in the burning frontier: A comprehensive review. Trees For. People 2024, 16, 100526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramo, R.; Roteta, E.; Bistinas, I.; Van Wees, D.; Bastarrika, A.; Chuvieco, E.; Van der Werf, G.R. African burned area and fire carbon emissions are strongly impacted by small fires undetected by coarse resolution satellite data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2011160118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataveli, G.; Jones, M.W.; Pereira, G.; Freitas, S.R.; Oliveira, V.; Silva Oliveira, B.; Aragão, L.E. How do emission factors contribute to the uncertainty in biomass burning emissions in the Amazon and Cerrado? Atmosphere 2025, 16, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wees, D.; van der Werf, G.R.; Randerson, J.T.; Rogers, B.M.; Chen, Y.; Veraverbeke, S.; Giglio, L.; Morton, D.C. Global biomass burning fuel consumption and emissions at 500-m spatial resolution based on the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED). Geosci. Model Dev. Discuss. 2022, 15, 8411–8437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.; Chen, J.; Anderson, K.; Makar, P.; McLinden, C.A.; Dammers, E.; Fogal, A. Biomass burning CO emissions: Exploring insights through TROPOMI-derived emissions and emission coefficients. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 10159–10186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bowman, K.W.; Schimel, D.S.; Parazoo, N.C.; Jiang, Z.; Lee, M.; Bloom, A.A.; Wunch, D.; Frankenberg, C.; Sun, Y.; et al. Contrasting carbon cycle responses of the tropical continents to the 2015–2016 El Niño. Science 2017, 358, eaam5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filonchyk, M.; Peterson, M.P. Changes in aerosol properties at the El Arenosillo site in Southern Europe as a result of the 2023 Canadian forest fires. Environ. Res. 2024, 260, 119629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Pippal, P.S.; Kumar, R.; Singh, A.; Singh, S.; Kumar, P.; Shrestha, S. Forest fire consequences under the influence of changing climate: A systematic review with bibliometric analysis in the context of sustainable development goals. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Santesso, N.; Guyatt, G.H. Systematic reviews of the literature: An introduction to current methods. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2025, 194, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarque, J.F.; Bond, T.C.; Eyring, V.; Granier, C.; Heil, A.; Klimont, Z.; Lee, D.; Liousse, C.; Mieville, A.; Owen, B.; et al. Historical (1850–2000) gridded anthropogenic and biomass burning emissions of reactive gases and aerosols: Methodology and application. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 7017–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieville, A.; Granier, C.; Liousse, C.; Guillaume, B.; Mouillot, F.; Lamarque, J.F.; Grégoire, J.M.; Pétron, G. Emissions of gases and particles from biomass burning during the 20th century using satellite data and an historical reconstruction. Atmos. Environ. 2010, 44, 1469–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, N.K.; Raffuse, S.M.; Strand, T.M. Wildland fire emissions, carbon, and climate: US emissions inventories. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 317, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yamaguchi, Y. A high-resolution and multi-year emissions inventory for biomass burning in Southeast Asia during 2001–2010. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 98, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Duan, L.; Chai, F.; Wang, S.; Yu, Q.; Wang, S. Deriving high-resolution emission inventory of open biomass burning in China based on satellite observations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 11779–11786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junpen, A.; Garivait, S.; Bonnet, S. Estimating emissions from forest fires in Thailand using MODIS active fire product and country specific data. Asia-Pac. J. Atmos. Sci. 2013, 49, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Wang, T.; Han, J.; Xu, B.; Ma, D.; Zhang, M.; Li, S.; Zhuang, B.; Li, M.; Xie, M. Spatial and temporal variation of air pollutant emissions from forest fires in China. Atmos. Environ. 2022, 281, 119156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Kong, S.; Wu, F.; Cheng, Y.; Zheng, S.; Yan, Q.; Zheng, H.; Yang, G.; Zheng, M.; Liu, D.; et al. Estimating the open biomass burning emissions in central and eastern China from 2003 to 2015 based on satellite observation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 11623–11646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permadi, D.A.; Oanh, N.T.K. Assessment of biomass open burning emissions in Indonesia and potential climate forcing impact. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 78, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Gong, S.; Zang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, W.; Lv, Z.; Matsunaga, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Bai, Y. High-resolution and multi-year estimation of emissions from open biomass burning in Northeast China during 2001–2017. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondur, V.G.; Zima, A.L.; Feoktistova, N.V. Long-term satellite monitoring of various types of wildfires and wildfire-induced emissions of climate-active gases and aerosols in Russia and in its large regions. Izvestiya, Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2024, 60, 1494–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, G.; Pozzoli, L.; Schmidt, C.C.; Unal, A.; Kindap, T.; Menzel, W.P.; Whitburn, S.; Coheur, P.F.; Kavgaci, A.; Kaiser, J.W. Using SEVIRI fire observations to drive smoke plumes in the CMAQ air quality model: A case study over Antalya in 2008. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 8539–8558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.; Monteiro, A.; Flannigan, M.; Solman, S.; Miranda, A.I.; Borrego, C. Forest fires in a changing climate and their impacts on air quality. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 5545–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Du, P.; Zhang, M.; Liu, M.; Xu, T.; Song, Y. Estimation of emissions from biomass burning in China (2003–2017) based on MODIS fire radiative energy data. Biogeosciences 2019, 16, 1629–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Kong, S.; Wu, F.; Cheng, Y.; Zheng, S.; Qin, S.; Liu, X.; Yan, Q.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, M.; et al. The moving of high emission for biomass burning in China: View from multi-year emission estimation and human-driven forces. Environ. Int. 2020, 142, 105812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhang, L.; Hou, B.; Wang, W.; Li, Q.; Li, Y. NPP and carbon emissions under forest fire disturbance in Southwest and Northeast China from 2001 to 2020. Forests 2023, 14, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Liao, J.; Min, J.; Gong, X.; Wang, D.; Gong, Z. The hidden carbon cost of forest fire management: Quantifying greenhouse gas emissions from both vegetation burning and social rescue activities in Yajiang county, China. Forests 2025, 16, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xu, Z.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, W.; Wang, W. Development of a finer-resolution multi-year emission inventory for open biomass burning in Heilongjiang Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, J.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, Y. Estimation of forest fire emissions in Southwest China from 2013 to 2017. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Jiang, X. High-resolution estimation of air pollutant emissions from vegetation burning in China (2000–2018). Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 896373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhujel, K.B.; Maskey Byanju, R.; Gautam, A.P.; Sapkota, R.P.; Khadka, U.R. Fire-induced carbon emissions from tropical mixed broad-leaved forests of the Terai–Siwalik region, central Nepal. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 2557–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korísteková, K.; Vido, J.; Vida, T.; Vyskot, I.; Mikloš, M.; Minďáš, J.; Škvarenina, J. Evaluating the amount of potential greenhouse gas emissions from forest fires in the area of the Slovak Paradise National Park. Biologia 2020, 75, 885–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, S.; Parida, B.R.; Pandey, A.C.; Kumar, N. Pixel-based long-term (2001–2020) estimations of forest fire emissions over the Himalaya. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartowitz, K.J.; Walsh, E.S.; Stenzel, J.E.; Kolden, C.A.; Hudiburg, T.W. Forest carbon emission sources are not equal: Putting fire, harvest, and fossil fuel emissions in context. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 867112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayet, N.; Eregowda, T.; Ganeshker, A.K.V.; Hegde, G. Development of 1 × 1 km gridded emission inventory for air quality assessment and mitigation strategies from open biomass burning in Karnataka, India. Urban Clim. 2024, 58, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.S.; Padma Alekhya, V.V.L.; Saranya, K.R.L.; Athira, K.; Jha, C.S.; Diwakar, P.G.; Dadhwal, V.K. Monitoring of fire incidences in vegetation types and Protected Areas of India: Implications on carbon emissions. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 126, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, K.R.L.; Reddy, C.S.; Rao, P.P. Estimating carbon emissions from forest fires over a decade in Similipal Biosphere Reserve, India. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2016, 4, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, N.C.; Chaffe, P.L.B.; Chagas, V.B.P.; Ribeiro, C.B.; Rodrigues Rodrigues, R.; Hoinaski, L. Recent fire occurrence and associated emissions in Southern Brazil. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2024, 18, 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditi, K.; Pandey, A.; Banerjee, T. Forest fire emission estimates over South Asia using Suomi-NPP VIIRS-based thermal anomalies and emission inventory. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 366, 125441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Song, Y. Estimates of biomass burning emissions in tropical Asia based on satellite-derived data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 2335–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zang, S.; Matsunaga, T.; Yamaguchi, Y. A multi-year and high-resolution inventory of biomass burning emissions in tropical continents from 2001–2017 based on satellite observations. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, V.; Miranda, A.I.; Carvalho, A.; Schaap, M.; Borrego, C.; Sá, E. Impact of forest fires on particulate matter and ozone levels during the 2003, 2004 and 2005 fire seasons in Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 414, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolin, M.L.; Urretavizcaya, M.F.; Defossé, G.E. Fire emissions and carbon uptake in severely burned lenga beech (Nothofagus pumilio) forests of Patagonia, Argentina. Fire Ecol. 2015, 11, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, C.; Bacciu, V.; Ascoli, D.; Costa-Saura, J.M.; Salis, M.; Sirca, C.; Marchetti, M.; Spano, D. Estimating annual GHG and particulate matter emissions from rural and forest fires based on an integrated modelling approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgiç, E.; Tuygun, G.T.; Gündüz, O. Development of an emission estimation method with satellite observations for significant forest fires and comparison with global fire emission inventories: Application to catastrophic fires of summer 2021 over the Eastern Mediterranean. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 308, 119871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Liu, H.; Dahal, D.; Jin, S.; Li, S.; Liu, S. Spatial variations in immediate greenhouse gases and aerosol emissions and resulting radiative forcing from wildfires in interior Alaska. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2016, 123, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.M.M.D.; Vasconcelos, R.N.D.; Mariano-Neto, E. Fire propensity in Amazon savannas and rainforest and effects under future climate change. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2023, 32, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Reis, M.; de Alencastro Graça, P.M.L.; Yanai, A.M.; Ramos, C.J.P.; Fearnside, P.M. Forest fires and deforestation in the central Amazon: Effects of landscape and climate on spatial and temporal dynamics. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 288, 112310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, T.A.; Jones, M.W.; Finney, D.; Van der Werf, G.R.; van Wees, D.; Xu, W.; Veraverbeke, S. Extratropical forests increasingly at risk due to lightning fires. Nat. Geosci. 2023, 16, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, S.L.; Burrows, N.; Buyantuyev, A.; Gray, R.W.; Keane, R.E.; Kubian, R.; Liu, S.; Seijo, F.; Shu, L.; Tolhurst, K.G.; et al. Temperate and boreal forest mega-fires: Characteristics and challenges. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 12, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agne, M.C.; Fontaine, J.B.; Enright, N.J.; Harvey, B.J. Fire interval and post-fire climate effects on serotinous forest resilience. Fire Ecol. 2022, 18, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, B.; Bratoev, I.; Crowley, M.A.; Zhu, Y.; Senf, C. Distribution and characteristics of lightning-ignited wildfires in boreal forests–the BoLtFire database. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2024, 17, 2249–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Fernández-Muñoz, S. Fire regime changes in the Western Mediterranean Basin: From fuel-limited to drought-driven fire regime. Clim. Change 2012, 110, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P.; Wang, S.; Oakes, J.M.; Bellini, C.; Gollner, M.J. Variations in gaseous and particulate emissions from flaming and smoldering combustion of Douglas fir and lodgepole pine under different fuel moisture conditions. Combust. Flame 2024, 263, 113386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, S.J.; O’Neill, S.M.; Eagle, P.; Andreu, A.G.; Drye, B.; Dubowy, J.; Urbanski, S.; Strand, T.M. Wildland fire emission factors in North America: Synthesis of existing data, measurement needs and management applications. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2020, 29, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, T.; Gullett, B.; Urbanski, S.; O’Neill, S.; Potter, B.; Aurell, J.; Holder, A.; Larkin, N.; Moore, M.; Rorig, M. Grassland and forest understorey biomass emissions from prescribed fires in the south-eastern United States–RxCADRE 2012. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2015, 25, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, C.K.; El Hajj, O.; McQueen, Z.; Poland, R.P.; Penland, R.; Roberts, E.T.; Choi, J.H.; Bai, B.; Anosike, A.; Kumar, K.V.; et al. Brown carbon emissions from biomass burning under simulated wildfire and prescribed-fire conditions. ACS ES&T Air 2024, 1, 1124–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekimoto, K.; Koss, A.R.; Gilman, J.B.; Selimovic, V.; Coggon, M.M.; Zarzana, K.J.; Yuan, B.; Lerner, B.M.; Brown, S.S.; Warneke, C.; et al. High-and low-temperature pyrolysis profiles describe volatile organic compound emissions from western US wildfire fuels. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 9263–9281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekimoto, K.; Coggon, M.M.; Gkatzelis, G.I.; Stockwell, C.E.; Peischl, J.; Soja, A.J.; Warneke, C. Fuel-type independent parameterization of volatile organic compound emissions from western US wildfires. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 13193–13204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, A.; Lecina-Diaz, J.; De Càceres, M.; Vayreda, J.; Retana, J. Fuel types and fire severity effects on atmospheric pollutant emissions in an extreme wind-driven wildfire. EGUsphere 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Rego, F.; Morgan, P.; Fernandes, P.; Hoffman, C. From fuels to smoke: Chemical processes. In Fire Science: From Chemistry to Landscape Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-López, M.I.; Manzo-Delgado, L.D.L.; Aguirre-Gómez, R.; Chuvieco, E.; Equihua-Benítez, J.A. Spatial distribution of forest fire emissions: A case study in three Mexican ecoregions. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, S.; Cooperdock, S.; Veraverbeke, S.; Walker, X.; Mack, M.C.; Goetz, S.J.; Baltzer, J.; Bourgeau-Chavez, L.; Burell, A.; Dieleman, C.; et al. Burned area and carbon emissions across northwestern boreal North America from 2001–2019. Biogeosciences 2023, 20, 2785–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.; Liu, J.; Bowman, K.W.; Pascolini-Campbell, M.; Chatterjee, A.; Pandey, S.; Miyazaki, K.; van der Werf, G.R.; Wunch, D.; Wennberg, P.O.; et al. Carbon emissions from the 2023 Canadian wildfires. Nature 2024, 633, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, H.; Sharma, V.; Shrivastava, V.; Kumar, P.; Kanga, S.; Sahu, N.; Meraj, G.; Farooq, M.; Singh, S.K. Impact of forest fires on air quality in Wolgan Valley, New South Wales, Australia—A mapping and monitoring study using google earth engine. Forests 2022, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapere, R.; Mailler, S.; Menut, L. The 2017 mega-fires in central Chile: Impacts on regional atmospheric composition and meteorology assessed from satellite data and chemistry-transport modelling. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehret, A.; Turquety, S.; George, M.; Hadji-Lazaro, J.; Clerbaux, C. Increase in carbon monoxide (CO) and aerosol optical depth (AOD) observed by satellites in the Northern Hemisphere over the summers of 2008–2023, linked to an increase in wildfires. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2025, 25, 6365–6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, L.; Shi, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Nath, B.; Niu, Z. Methane emissions in boreal forest fire regions: Assessment of five biomass-burning emission inventories based on carbon sensing satellites. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Shan, Y.; Yin, S.; Cao, L.; Chen, X.; Xie, W.; Yu, M.; Feng, S. Recent advancements in the emission characteristics of forest ground smoldering combustion. Forests 2024, 15, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Werf, G.R.; Randerson, J.T.; Giglio, L.; Van Leeuwen, T.T.; Chen, Y.; Rogers, B.M.; Mu, M.; van Marle, M.J.E.; Morton, D.C.; Collatz, G.J.; et al. Global fire emissions estimates during 1997–2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 697–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagi, S.K.; Yokelson, R.J.; Wiedinmyer, C.; Alvarado, M.J.; Reid, J.S.; Karl, T.; Crounse, J.D.; Wennberg, P.O. Emission factors for open and domestic biomass burning for use in atmospheric models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 4039–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frausto-Vicencio, I.; Heerah, S.; Meyer, A.G.; Parker, H.A.; Dubey, M.; Hopkins, F.M. Ground solar absorption observations of total column CO, CO2, CH4, and aerosol optical depth from California’s Sequoia Lightning Complex Fire: Emission factors and modified combustion efficiency at regional scales. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 4521–4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreae, M.O.; Merlet, P. Emission of trace gases and aerosols from biomass burning. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2001, 15, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K., Meyer, L.A., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, S.F.; Richter, A.; Schepaschenko, D.; Shvidenko, A.; Hilboll, A.; Burrows, J.P. Differences in satellite-derived NOx emission factors between Eurasian and North American boreal forest fires. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 121, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, S.F.; Richter, A.; Kaiser, J.W.; Burrows, J.P. The empirical relationship between satellite-derived tropospheric NO2 and fire radiative power and possible implications for fire emission rates of NOx. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 2447–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, N.; Xiong, X.; Kluitenberg, G.J.; Hutchinson, J.M.; Aiken, R.; Zhao, H.; Lin, X. Estimation of biomass burning emission of NO2 and CO from 2019–2020 Australia fires based on satellite observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, C.D.; Janz, S.J.; Lamsal, L.N.; Jongebloed, U.A.; Laughner, J.L.; Thornton, J.A. Remote sensing estimates of time-resolved HONO and NO2 emission rates and lifetimes in wildfires. Atmos. Meas. Tech. Discuss. 2024, 2024, 3669–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarín-Carrasco, P.; Augusto, S.; Palacios-Penã, L.; Ratola, N.; Jiménez-Guerrero, P. Impact of large wildfires on PM10 levels and human mortality in Portugal. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 21, 2867–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurrohman, R.K.; Kato, T.; Ninomiya, H.; Végh, L.; Delbart, N.; Miyauchi, T.; Sato, H.; Shiraishi, T.; Hirata, R. Future projections of Siberian wildfire and aerosol emissions. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 4195–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Ma, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, C.; Lin, H.; Tigabu, M.; Guo, F. Temporal and spatial dynamics in emission of water-soluble ions in fine particulate matter during forest fires in Southwest China. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1250038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; He, J.; Wooster, M.J. Biomass burning CO, PM and fuel consumption per unit burned area estimates derived across Africa using geostationary SEVIRI fire radiative power and Sentinel-5P CO data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 2089–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanski, S.P. Combustion efficiency and emission factors for wildfire-season fires in mixed conifer forests of the northern Rocky Mountains, US. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 7241–7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, E.B.; Andrews, A.; Sweeney, C.; Miller, J.B.; Miller, C.E.; Veraverbeke, S.; Commane, R.; Wofsy, S.; Henderson, J.M.; Randerson, J.T. Boreal Forest fire CO and CH4 emission factors derived from tower observations in Alaska during the extreme fire season of 2015. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 8557–8574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgarakis, A.; Field, R.D. Fire influences on atmospheric composition, air quality and climate. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2015, 1, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.R.; Abbatt, J.P. Wildfire atmospheric chemistry: Climate and air quality impacts. Trends Chem. 2022, 4, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Yue, X.; Zhu, J.; Liao, H.; Yang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, H.; Ma, Y.; Cao, Y. Fire–climate interactions through the aerosol radiative effect in a global chemistry–climate–vegetation model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 12353–12366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhawar, R.L.; Kumar, V.; Lawand, D.; Kedia, S.; Naik, M.; Modale, S.; Reddy, P.R.C.; Islam, S.; Khare, M. Aerosol emission patterns from the February 2019 Karnataka fire. Fire 2024, 7, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.S.; Kloster, S.; Mahowald, N.M.; Rogers, B.M.; Randerson, J.T.; Hess, P.G. The changing radiative forcing of fires: Global model estimates for past, present and future. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 10857–10886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernath, P.; Boone, C.; Crouse, J. Wildfire smoke destroys stratospheric ozone. Science 2022, 375, 1292–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salawitch, R.J.; McBride, L.A. Australian wildfires depleted the ozone layer. Science 2022, 378, 829–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lu, X.; Fung, J.C.; Wong, D.C.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, W. Investigating Southeast Asian biomass burning by the WRF-CMAQ two-way coupled model: Emission and direct aerosol radiative effects. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 294, 119521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Yue, X.; Liao, H.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Tian, C.; Gong, C.; Ma, Y.; Gao, L.; et al. Indirect contributions of global fires to surface ozone through ozone–vegetation feedback. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 11531–11543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Mickley, L.J.; Logan, J.A.; Hudman, R.C.; Martin, M.V.; Yantosca, R.M. Impact of 2050 climate change on North American wildfire: Consequences for ozone air quality. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 10033–10055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.A.; Campbell, J.R.; Hyer, E.J.; Fromm, M.D.; Kablick III, G.P.; Cossuth, J.H.; DeLand, M.T. Wildfire-driven thunderstorms cause a volcano-like stratospheric injection of smoke. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2018, 1, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.; Stone, K.; Yu, P.; Murphy, D.M.; Kinnison, D.; Ravishankara, A.R.; Wang, P. Chlorine activation and enhanced ozone depletion induced by wildfire aerosol. Nature 2023, 615, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friberg, J.; Martinsson, B.G.; Sporre, M.K. Short-and long-term stratospheric impact of smoke from the 2019–2020 Australian wildfires. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 12557–12570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.A.; Fromm, M.D.; McRae, R.H.; Campbell, J.R.; Hyer, E.J.; Taha, G.; Camacho, C.P.; Kablick, G.P.; Schmidt, C.C.; DeLand, M.T. Australia’s Black Summer pyrocumulonimbus super outbreak reveals potential for increasingly extreme stratospheric smoke events. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaykin, S.; Legras, B.; Bucci, S.; Sellitto, P.; Isaksen, L.; Tencé, F.; Bekki, S.; Bourassa, A.; Rieger, L.; Zawada, D.; et al. The 2019/20 Australian wildfires generated a persistent smoke-charged vortex rising up to 35 km altitude. Commun. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damany-Pearce, L.; Johnson, B.; Wells, A.; Osborne, M.; Allan, J.; Belcher, C.; Jones, A.; Haywood, J. Australian wildfires cause the largest stratospheric warming since Pinatubo and extends the lifetime of the Antarctic ozone hole. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, O.; Bhartia, P.K.; Taha, G.; Jethva, H.; Das, S.; Colarco, P.; Krotkov, N.; Omar, A.; Ahn, C. Stratospheric injection of massive smoke plume from Canadian boreal fires in 2017 as seen by DSCOVR-EPIC, CALIOP, and OMPS-LP observations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2020, 125, e2020JD032579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Colarco, P.R.; Oman, L.D.; Taha, G.; Torres, O. The long-term transport and radiative impacts of the 2017 British Columbia pyrocumulonimbus smoke aerosols in the stratosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 12069–12090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohneiser, K.; Ansmann, A.; Baars, H.; Seifert, P.; Barja, B.; Jimenez, C.; Radenz, M.; Teisseire, A.; Floutsi, A.; Haarig, M.; et al. Smoke of extreme Australian bushfires observed in the stratosphere over Punta Arenas, Chile, in January 2020: Optical thickness, lidar ratios, and depolarization ratios at 355 and 532 nm. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 8003–8015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaykin, S.; Bekki, S.; Godin-Beekmann, S.; Fromm, M.D.; Goloub, P.; Hu, Q.; Josse, B.; Laeng, A.; Meziane, M.; Peterson, D.A.; et al. Stratospheric impact of the anomalous 2023 Canadian wildfires: The two vertical pathways of smoke. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2025, 25, 14551–14571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, L.A.; Randel, W.J.; Bourassa, A.E.; Solomon, S. Stratospheric temperature and ozone anomalies associated with the 2020 Australian New Year fires. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL095898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Forest fire emissions: A contribution to global climate change. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 925480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, M.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z. Impacts of wildfire aerosols on global energy budget and climate: The role of climate feedbacks. J. Clim. 2020, 33, 3351–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditto, J.C.; He, M.; Hass-Mitchell, T.N.; Moussa, S.G.; Hayden, K.; Li, S.M.; Liggio, J.; Leithead, A.; Lee, P.; Wheeler, M.J.; et al. Atmospheric evolution of emissions from a boreal forest fire: The formation of highly functionalized oxygen-, nitrogen-, and sulphur-containing compounds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2020, 21, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Liu, Z.; Li, K.; Guo, W.; Zhou, S.; Guan, R.; Wang, W. Influence of forest cover loss on land surface temperature differs by drivers in China. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2024, 129, e2024JG008103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ballantyne, A.P.; Cooper, L.A. Increases in land surface temperature in response to fire in Siberian boreal forests and their attribution to biophysical processes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 6485–6494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbig, M.; Daw, L.; Iwata, H.; Rudaitis, L.; Ueyama, M.; Živković, T. Boreal forest fire causes daytime surface warming during summer to exceed surface cooling during winter in North America. AGU Adv. 2024, 5, e2024AV001327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pye, H.O.T.; Xu, L.; Henderson, B.H.; Pagonis, D.; Campuzano-Jost, P.; Guo, H.; Jimenez, J.L.; Allen, C.; Skipper, T.N.; Halliday, H.S.; et al. Evolution of reactive organic compounds and their potential health risk in wildfire smoke. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 19785–19796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Wu, Y.; Xu, R.; Guo, Y.; Li, S. Excess emergency department visits for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases during the 2019–20 bushfire period in Australia: A two-stage interrupted time-series analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 809, 152226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongpiachan, S.; Tipmanee, D.; Khumsup, C.; Kittikoon, I.; Hirunyatrakul, P. Assessing risks to adults and preschool children posed by PM2.5-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (pahs) during a biomass burning episode in Northern Thailand. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 508, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maji, K.J.; Li, Z.; Hu, Y.; Vaidyanathan, A.; Stowell, J.D.; Milando, C.; Wellenius, G.; Kinney, P.L.; Russell, A.G.; Talat Odman, M. Prescribed burn related increases of population exposure to PM2.5 and O3 pollution in the southeastern US over 2013–2020. Environ. Int. 2024, 193, 109101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.V.; Nunes, R.A.O.; Alvim-Ferraz, M.C.M.; Martins, F.G.; Sousa, S.I.V. Health and economic burden of wildland fires PM2.5-related pollution in Portugal—A longitudinal study. Environ. Res. 2024, 240, 117490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, L.; Veronez, M.R.; de Souza, E.M.; Brum, D.; Gonzaga, L.; Rofatto, V.F. Respiratory diseases, malaria and leishmaniasis: Temporal and spatial association with fire occurrences from knowledge discovery and data mining. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooster, M.J.; Gaveau, D.L.A.; Salim, M.A.; Zhang, T.; Xu, W.; Green, D.C.; Huijnen, V.; Murdiyarso, D.; Gunawan, D.; Borchard, N.; et al. New tropical peatland gas and particulate emissions factors indicate 2015 Indonesian fires released far more particulate matter (but less methane) than current inventories imply. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Shi, Y.; Zheng, W.; Shan, T.; Wang, G. Global emissions inventory from open biomass burning (GEIOBB): Utilizing Fengyun-3D global fire spot monitoring data. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 3495–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Si, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, F.; Lu, X.; Li, X.; Sun, D.; Wang, Z. The relationship between PM2.5 and eight common lung diseases: A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis. Toxics 2024, 12, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, V.C.; Kazemiparkouhi, F.; Manjourides, J.; Suh, H.H. Long-term PM2.5 exposure and respiratory, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality in older US adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 186, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, H.; Türkan, H.; Vucinic, S.; Naqvi, S.; Bedair, R.; Rezaee, R.; Tsatsakis, A. Carbon monoxide poisoning. Toxicol. Rep. 2020, 7, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G.; Wooster, M.J. Global impact of landscape fire emissions on surface level PM2.5 concentrations, air quality exposure and population mortality. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 252, 118210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, C.J.; Egyed, M.; Xi, G.; Racine, J.; Pavlovic, R.; Rittmaster, R.; Handerson, S.B.; Stieb, D.M. Health impact analysis of PM2.5 from wildfire smoke in Canada (2013–2015, 2017–2018). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 725, 138506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, W.S.; Schmidt, R.J.; Sanghar, G.K.; Thompson Iii, G.R.; Ji, H.; Zeki, A.A.; Haczku, A. “air that once was breath” Part 1: Wildfire-smoke-induced mechanisms of airway inflammation–“climate change, allergy and immunology” Special IAAI Article Collection: Collegium Internationale Allergologicum Update 2023. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 185, 600–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Location | References | CO2 (Tg) | CH4 (Tg) | NOx (Tg) | CO (Tg) | PM2.5 (Tg) | PM10 (Tg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperate | China | Qiu et al. [36] | 7.69 | 0.021 | 0.015 | 0.331 | 0.048 | 0.068 |

| Song et al. [38] | 1.70 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.104 | 0.011 | - | ||

| Wu et al. [39] | 62.71 | 0.234 | - | 3.530 | 0.338 | - | ||

| Shi et al. [41] | 2027.90 | 3.617 | 3.997 | 87.137 | 9.877 | - | ||

| Yin et al. [45] | 91.41 | 0.236 | 0.231 | 5.02 | 0.506 | 0.567 | ||

| Wu et al. [46] | 962.04 | 2.978 | 1.422 | 54.163 | 4.387 | 5.034 | ||

| Zhang et al. [47] | 6.00 | 0.019 | - | 0.370 | - | - | ||

| Ye et al. [48] | 0.05 | 0 | 0.063 | 0.004 | - | - | ||

| Li et al. [49] | 17.20 | 0.064 | 0.040 | 0.907 | 0.129 | 0.184 | ||

| Wang et al. [50] | 1.25 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.081 | 0.001 | 0.005 | ||

| Yang & Jiang. [51] | 22.45 | 0.043 | 0.034 | 1.127 | 0.140 | 0.200 | ||

| Nepal | Bhujel et al. [52] | 0.001 | 0.001 | - | 0.001 | - | - | |

| Slovakia | Korísteková et al. [53] | 2.44 | 0.01 | - | 0.193 | 0.015 | 0.017 | |

| Himalaya | Bar et al. [54] | 13.60 | 0.042 | 0.013 | 0.840 | 0.104 | 0.115 | |

| United States | Bartowitz et al. [55] | 23.11 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Larkin et al. [34] | 65.5 | 0.181 | 0.154 | - | 0.403 | - | ||

| Tropical | Indian | Kayet et al. [56] | 7.98 | 0.031 | 0.008 | 0.642 | 0.077 | 0.094 |

| Reddy et al. [57] | 98.11 | 0.33 | 0.010 | 5.690 | - | - | ||

| Saranya et al. [58] | 2.08 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.127 | - | - | ||

| Indonesia | Permadi & Oanh [40] | 57.25 | 0.401 | 0.098 | 7.411 | - | - | |

| Shi and Yamaguchi [35] | 54.88 | 0.236 | 0.056 | 3.612 | - | - | ||

| Thailand | Junpen et al. [37] | 171.12 | 0.736 | - | 11.263 | 0.970 | 0.906 | |

| Brazil | Teixeira et al. [59] | 7.82 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.418 | 0.042 | - | |

| South Asia | Aditi et al. [60] | 91.47 | 0.272 | - | - | 0.620 | - | |

| Tropical country | Chang & Song [61] | 131.67 | 0.892 | 0.115 | 11.500 | 3.492 | 3.775 | |

| Tropical Continent | Shi et al. [62] | 31.06 | 0.095 | 0.070 | 1.605 | 0.224 | 0.322 | |

| Mediterranean | Portugal | Carvalho et al. [44] | 1.01 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.062 | 0.068 | 0.074 |

| Martins et al. [63] | 4.14 | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.274 | 0.021 | 0.032 | ||

| Turkey | Baldassarre et al. [43] | - | - | 0.003 | 0.102 | 0.029 | - | |

| Argentina | Bertolin et al. [64] | 0.07 | 0.005 | - | 0.026 | - | - | |

| Italy | Scarpa et al. [65] | 2.02 | 0.011 | - | 0.221 | 0.018 | 0.022 | |

| Greece | Bilgic et al. [66] | - | - | 0.014 | 0.396 | 0.033 | - | |

| Boreal | Russia | Bondur et al. [42] | 184.89 | 0.479 | - | 9.014 | 1.077 | - |

| Alaska | Huang et al. [67] | 59.33 | 0.237 | 1.179 | 5.041 | - | - | |

| - | World | Lamarque et al. [32] | - | - | 54.648 | 332.131 | - | - |

| - | World | Mieville et. al. [33] | 8820.56 | - | 20.956 | 501 | - | - |

| References | Location | Year | O3 Before Fire (ppbv) | O3 After Fire (ppbv) | Difference (ppbv) | Percentage of Increased (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adame et al. [12] | Doñana Natural Park, Spanyol | 2017 | 31 | 484 | 453 | 1461.3 |

| Tropical area | 2017 | 25 | 61 | 36 | 144.0 | |

| Huang et al. [113] | Indo–China | 2015 | 39.3 | 48.6 | 9.3 | 23.7 |

| Yunnan-Guizhou | 2015 | 45.5 | 52.3 | 6.8 | 14.9 | |

| Guangdong-Guangxi | 2015 | 30.7 | 32.5 | 1.8 | 5.9 | |

| Hainan | 2015 | 35.1 | 38 | 2.9 | 8.3 | |

| Taiwan | 2015 | 34.1 | 36.9 | 2.8 | 8.2 | |

| Indo–China | 2015 | 38.5 | 42.2 | 3.7 | 9.6 | |

| Yunnan-Guizhou | 2015 | 49 | 50.4 | 1.4 | 2.9 | |

| Guangdong-Guangxi | 2015 | 37 | 38.7 | 1.7 | 4.6 | |

| Hainan | 2015 | 39.8 | 41.8 | 2 | 5.0 | |

| Taiwan | 2015 | 36 | 36.7 | 0.7 | 1.9 | |

| Lapere et al. [87] | Chile | 2017 | 55 | 65 | 10 | 18.2 |

| Lei et al. [114] | Global | 2005-2012 | 23.9 | 25.1 | 1.2 | 5.0 |

| Yue et al. [115] | Projection North America | 2050 | 40 | 42 | 2 | 5 |

| Projection Canada | 2050 | 20 | 25 | 5 | 25 | |

| Projection Alaska | 2050 | 20 | 35 | 15 | 75 |

| References | Location | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Reddy et al. [57] | India | Seasonal temperature rose 0.61 °C marking 2012 as the 2nd warmest year since 1901 and land precipitation decreases by 0.180 ± 0.966 mm/month |

| Bhawar et al. [109] | India | Fire events caused 10–14 W/m2 forcing, warming rate 0.002–0.005 K/day. |

| Lv et al. [130] | China | Post-fire land surface temperature increased by 0.11 °C after one year. |

| Liu et al. [131] | Siberia | Boreal fires caused net warming (0.07–0.325 K) with summer heating and winter cooling |

| Huang et al. [67] | Alaska | Mean radiative forcing 7.41 ± 2.87 W/m2 with strong spatial variation |

| Helbig et al. [132] | North America | Surface temperature in Canadian boreal forest 2024 increased 0.27 °C (summer) and decreased 0.02 °C (winter) after fire |

| Tian et al. [108] | Global | Fire emissions reduced net radiation (0.565 W/m2) and surface air temperature (0.061 °C); cooling > 0.25 °C in Amazon, US, and boreal Asia |

| Jiang et al. [128] | Global | Aerosols induced radiative effect (20.78 W m−2), reduced rainfall, and cooled Arctic regions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hadiwijoyo, E.; Rijal, H.B.; Abdullah, N. Cascading Impacts of Wildfire Emissions on Air Quality, Human Health, and Climate Change Based on Literature Review. Fire 2025, 8, 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120471

Hadiwijoyo E, Rijal HB, Abdullah N. Cascading Impacts of Wildfire Emissions on Air Quality, Human Health, and Climate Change Based on Literature Review. Fire. 2025; 8(12):471. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120471

Chicago/Turabian StyleHadiwijoyo, Erekso, Hom Bahadur Rijal, and Norhayati Abdullah. 2025. "Cascading Impacts of Wildfire Emissions on Air Quality, Human Health, and Climate Change Based on Literature Review" Fire 8, no. 12: 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120471

APA StyleHadiwijoyo, E., Rijal, H. B., & Abdullah, N. (2025). Cascading Impacts of Wildfire Emissions on Air Quality, Human Health, and Climate Change Based on Literature Review. Fire, 8(12), 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120471