Study on the Effectiveness of Perfluorohexanone in Extinguishing Small-Scale Pool Fires in Enclosed Compartments Under Low-Pressure Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

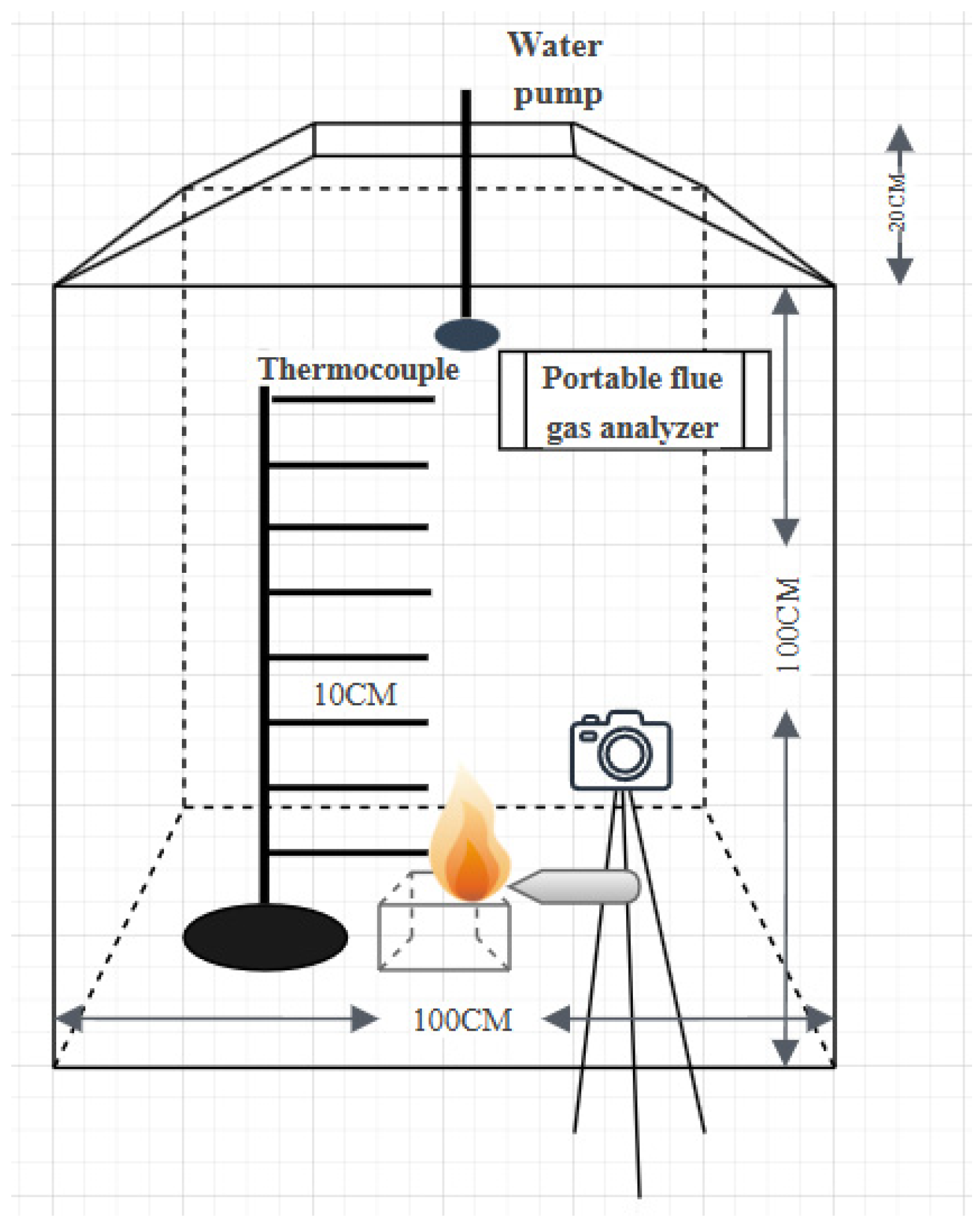

2. Experimental Setup and Methodology

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Experimental Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

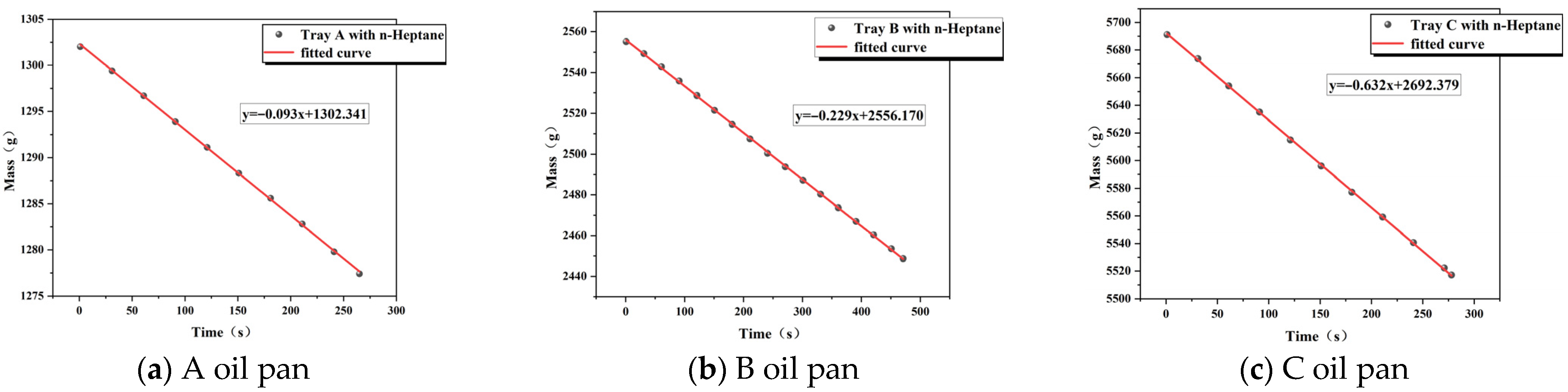

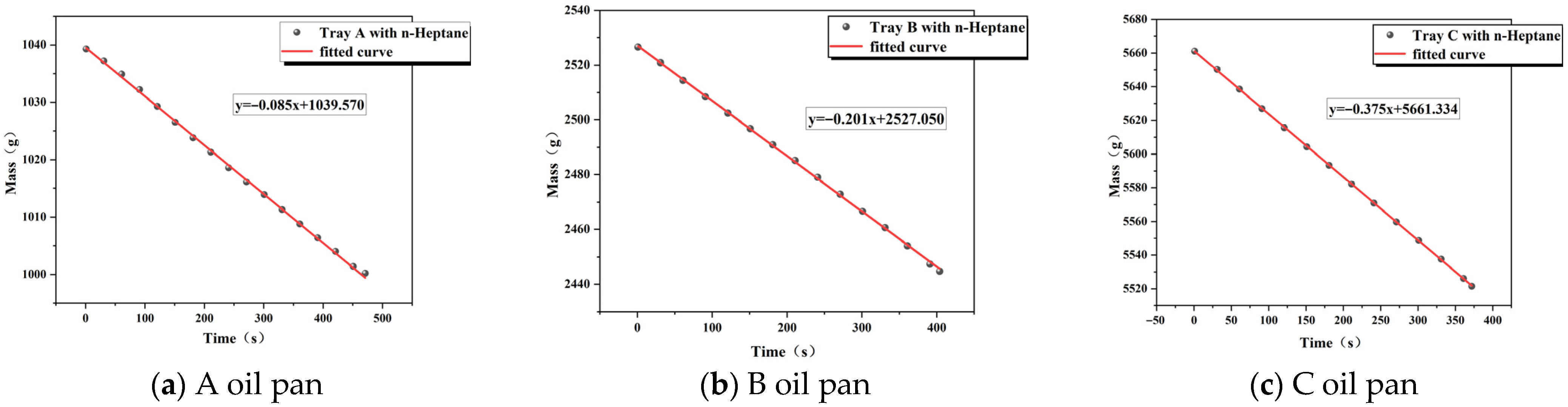

3.1. Measurement of Heat Release Rate

3.2. Fire Suppression Experiments

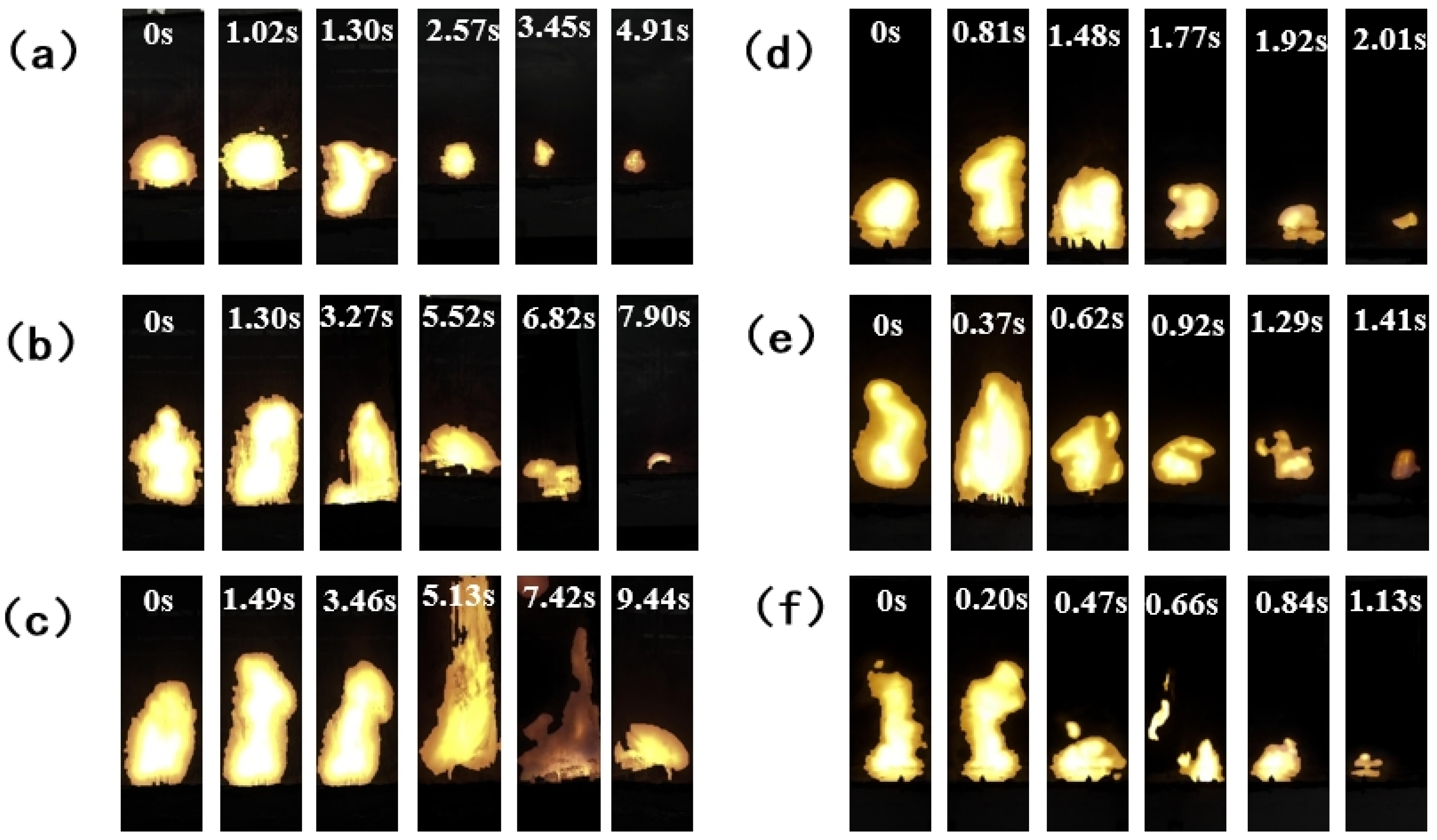

3.2.1. Visualization of the Extinguishing Process

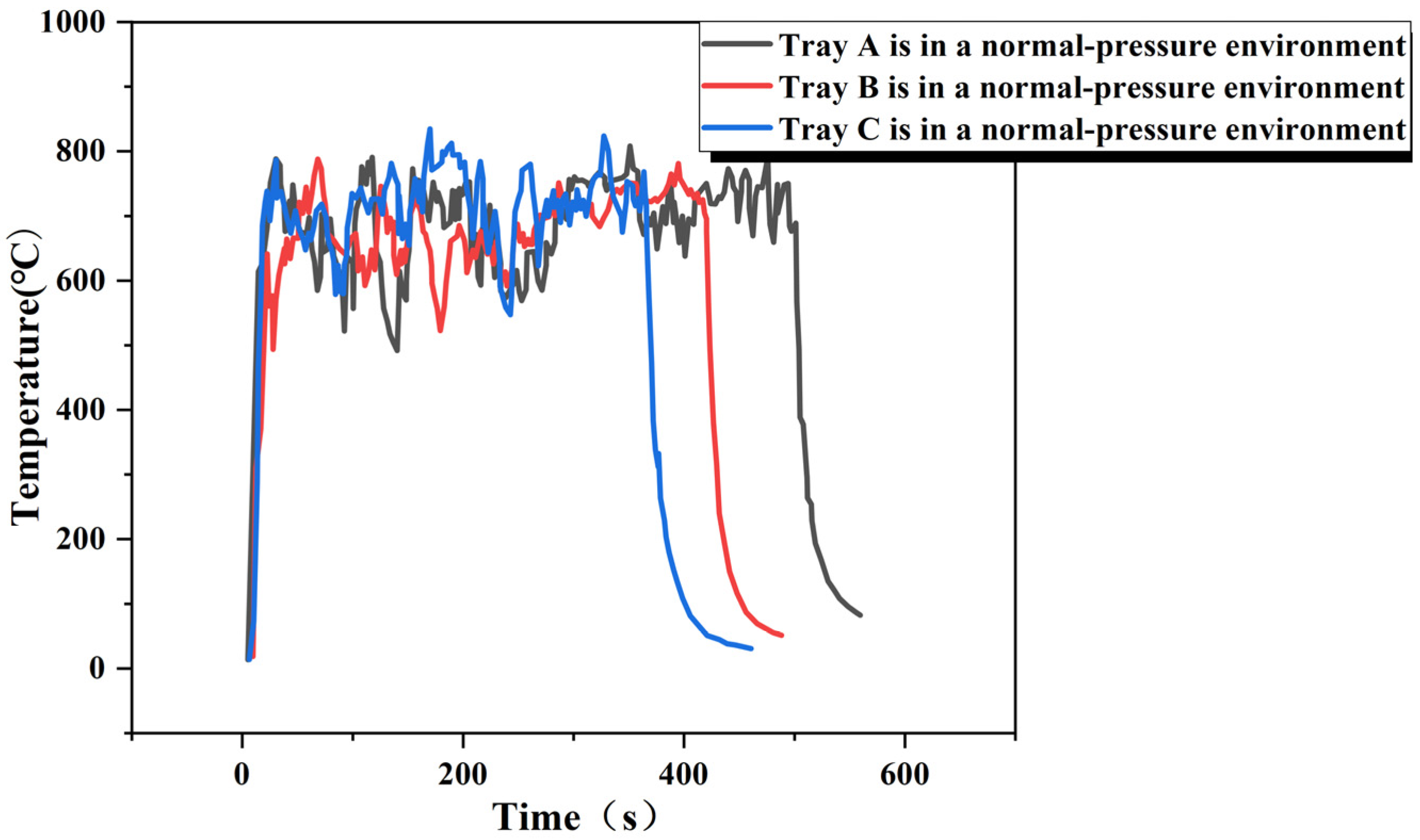

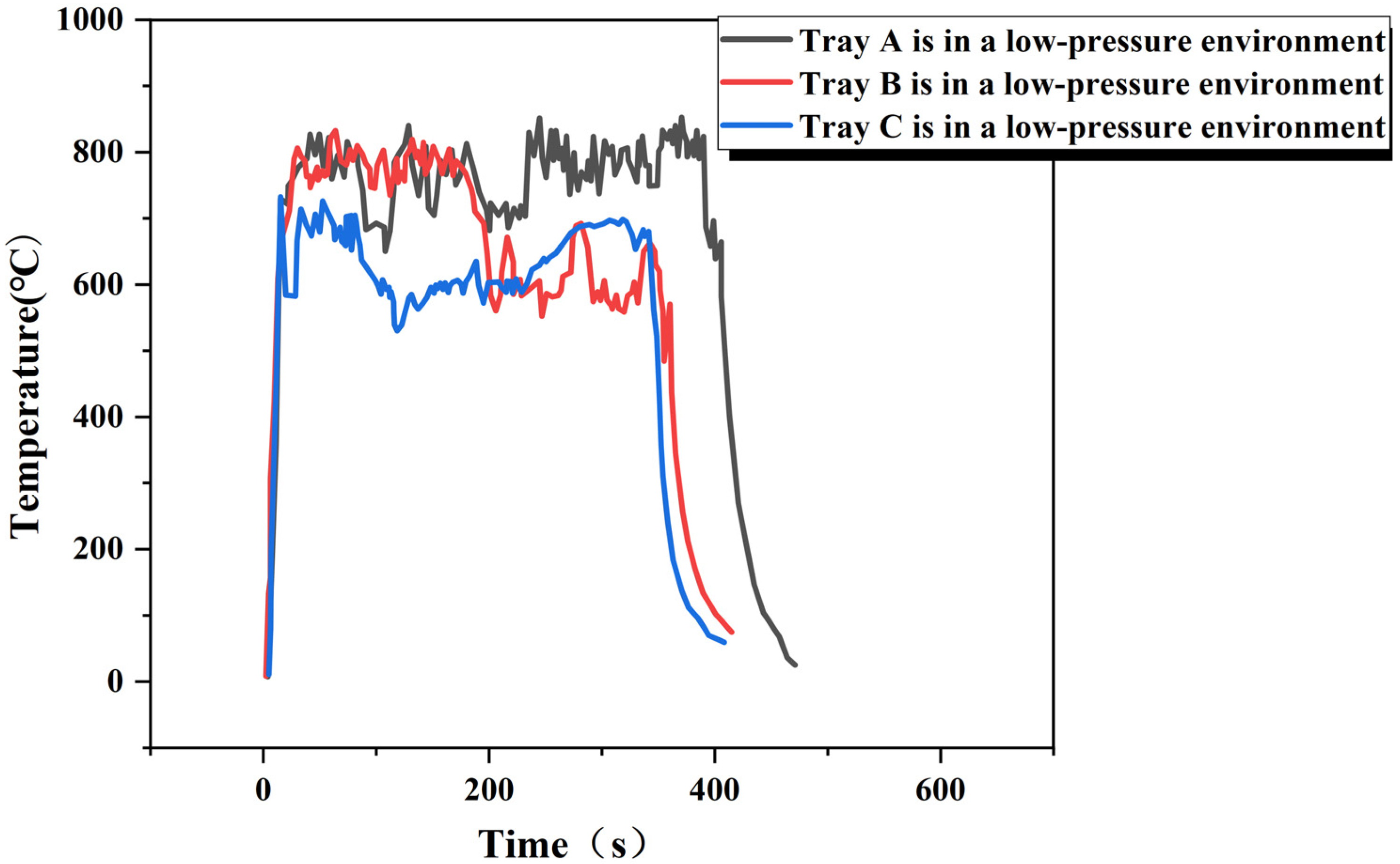

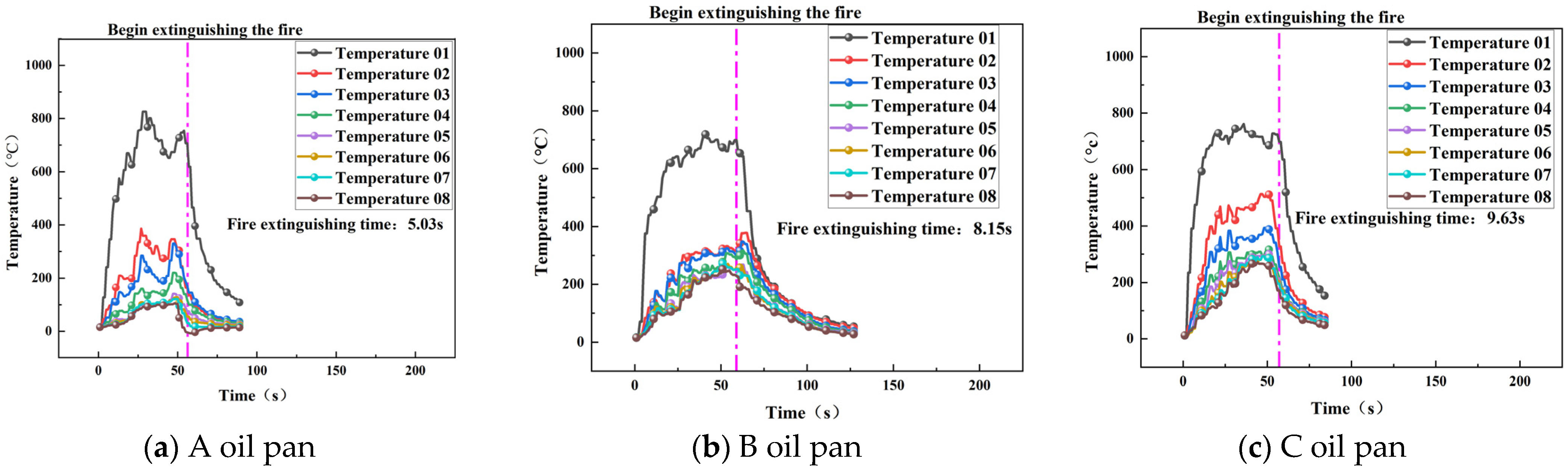

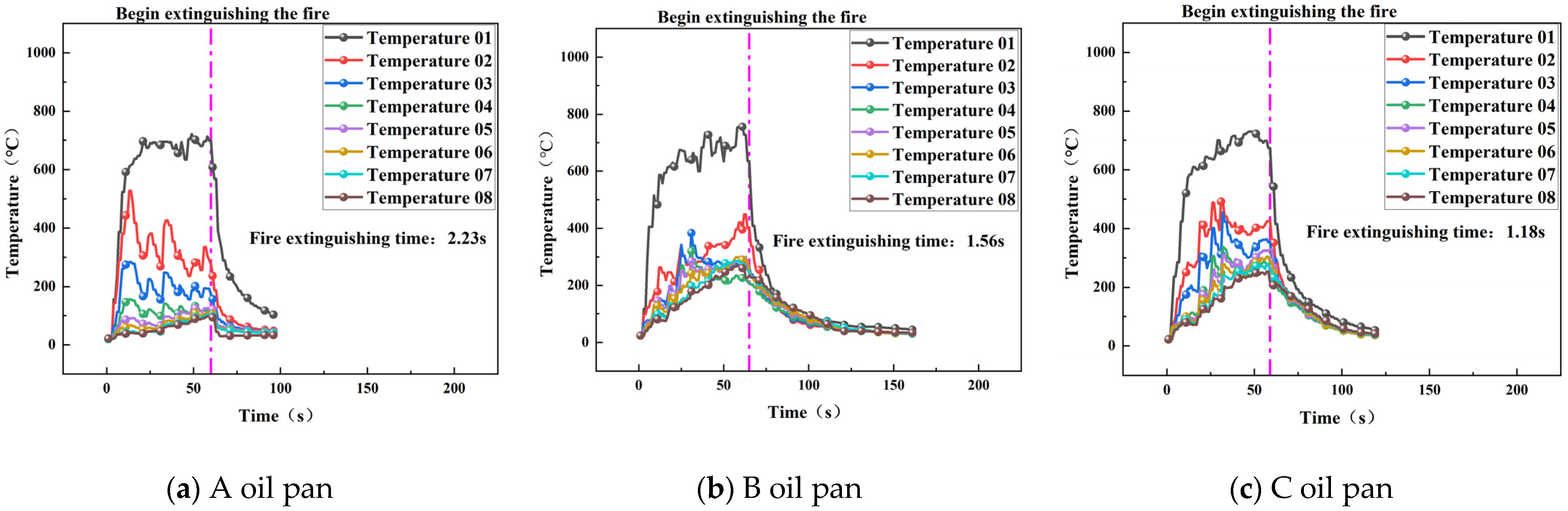

3.2.2. Extinguishing Time and Temperature

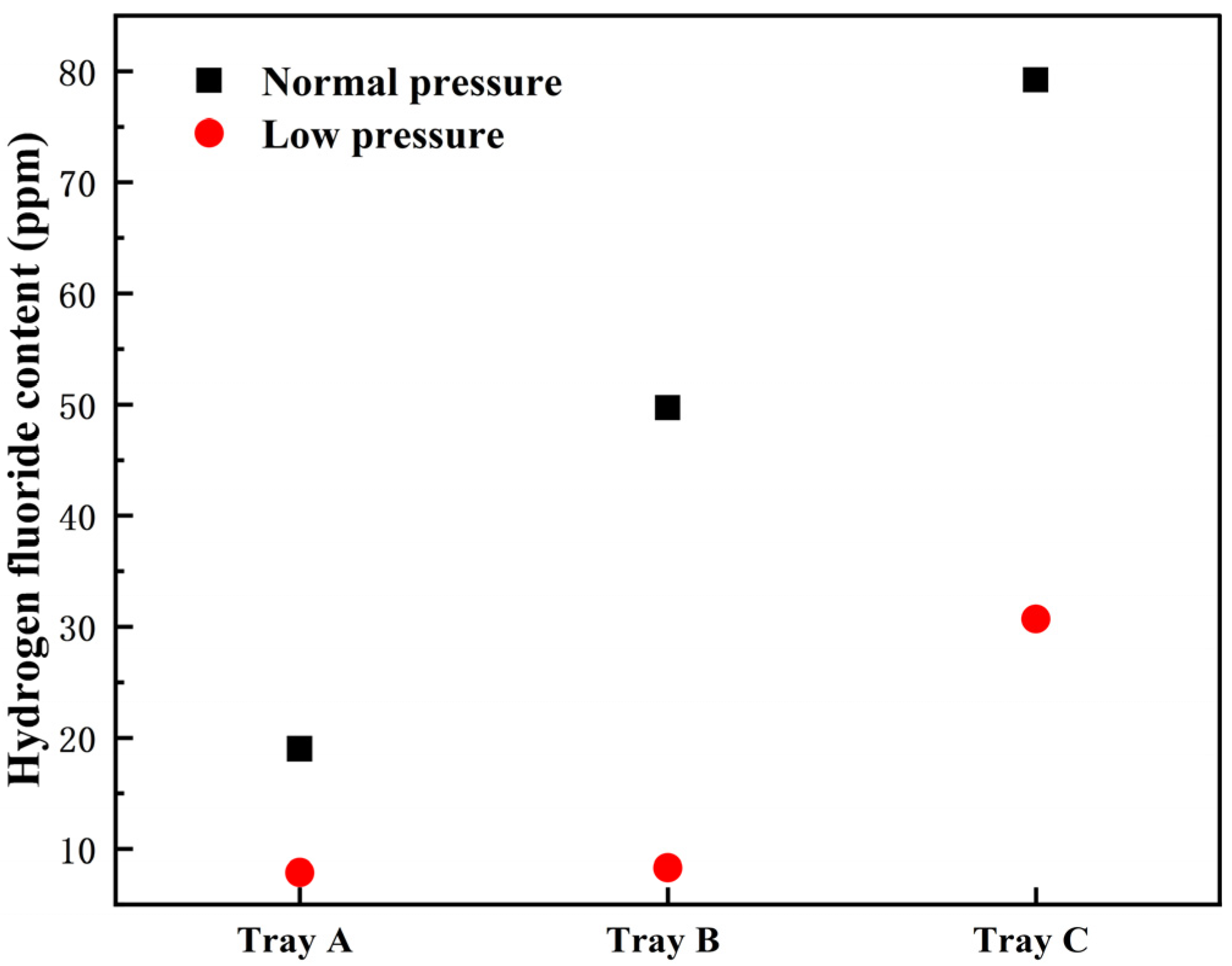

3.2.3. HF Measurement Results

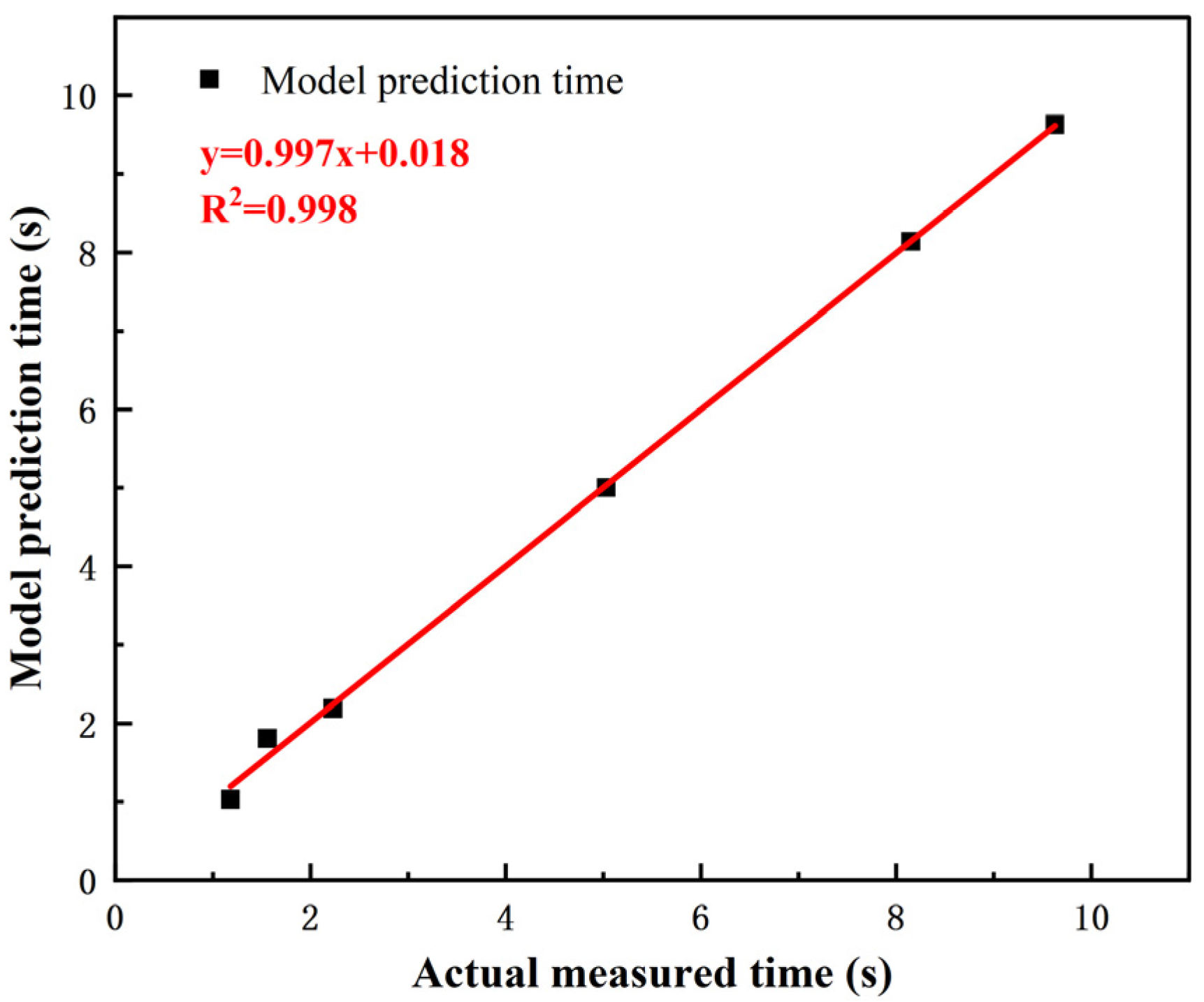

3.2.4. Extinguishing Effectiveness Model

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burkholder, J.B.; Cox, R.A.; Ravishankara, A.R. Atmospheric Degradation of Ozone Depleting Substances, Their Substitutes, and Related Species. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 3704–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F.; Katta, V.R.; Linteris, G.T.; Babushok, V.I. Combustion Inhibition and Enhancement of Cup-Burner Flames by CF3Br, C2HF5, C2HF3Cl2, and C3H2F3Br. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2015, 35, 2741–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F.; Katta, V.R.; Linteris, G.T.; Babushok, V.I. A Computational Study of Extinguishment and Enhancement of Propane Cup-Burner Flames by Halon and Alternative Agents. Fire Saf. J. 2017, 91, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gann, R.G. Next-Generation Fire Suppression Technology Program. Fire Technol. 1998, 34, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.C.; Wilding, W.V.; Wilson, G.M.; Rowley, R.L.; Felix, V.M.; Chisolmcarter, T. Thermophysical Properties of HFC-125. Fluid Phase Equilibria 1992, 80, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifke, J.; Martinez, A.; Tapscott, R.E.; Mather, J.D. Tropodegradable Bromocarbon Extinguishants. Available online: http://www.bfrl.nist.gov/866/NGP/publications/Tropo_Final_Rpt.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Lemmon, E.W.; Jacobsen, R.T. A New Functional form and New Fitting Techniques for Equations of State with Application to Pentafluoroethane (HFC-125). J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2005, 34, 69–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, D.S.; Laesecke, A. Sealed Gravitational Capillary Viscometry of Dimethyl Ether and Two Next-Generation Alternative Refrigerants. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 2012, 117, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, A.; Benson, C.M.; Holborn, P.G.; Sampath, S.; Xiong, Y. Performance Evaluation of Nitrogen for Fire Safety Application in Aircraft. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 202, 107044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, N.; Wallington, T.J.; Hurley, M.D.; Guschin, A.G.; Molina, L.T.; Molina, M.J. Atmospheric Chemistry of C2F5C(O)CF(CF3)2: Photolysis and Reaction with Cl Atoms, OH Radicals, and Ozone. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 2674–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tian, S.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Q.; Chen, D.; Cui, Z.; Tang, J. Insight into the Compatibility Between C6F12O and Metal Materials: Experiment and Theory. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 58154–58160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K. Measurement of pρT Properties of 1,1,1,2,2,4,5,5,5-Nonafluoro-4-(trifluoromethyl)-3-pentanone in the Near-Critical and Supercritical Regions. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2016, 61, 3958–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.Y.; Meng, X.Y.; Huber, M.L.; Wu, J.T. Measurement and Correlation of the Viscosity of 1,1,1,2,2,4,5,5,5-Nonafluoro-4-(trifluoromethyl)-3-pentanone. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2017, 62, 3603–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, R.A.; Huber, M.L.; Assael, M.J. Measurement and Correlation of the Thermal Conductivity of 1,1,1,2,2,4,5,5,5-Nonafluoro-4-(trifluoromethyl)-3-pentanone. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2018, 63, 2783–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.W.; Zou, G.W.; Liu, C.L.; Gao, Y. Comparison of Fire Extinguishing Performance of Four Halon Substitutes and Halon 1301. J. Fire Sci. 2021, 39, 370–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Jin, K.Q.; Liu, P.J.; Wang, C.D.; Xu, J.J.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.S. The Efficiency of Perfluorohexanone on Suppressing Lithium-Ion Battery Fire and Its Device Development. Fire Technol. 2023, 59, 1283–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; He, Y.; Huang, J. Numerical Simulation of Atomization Characteristics of Perfluorohexanone under Low-Pressure Environment. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Industrial Technology Applications (AIITA 2023), Suzhou, China, 24–26 March 2023; p. 012088. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Jin, J.Q.; Liang, J.X.; He, Y.H.; Chen, Y.G. Experimental Study on Fire Suppression of NCM Lithium-Ion Battery by C6F12O in A Confined Space. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 259, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.Z.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhou, H.Y.; Zhao, J.C. Experimental Study of the Strategy of C6F12O and Water Mist Intermittent Spray to Suppress Lithium-Ion Batteries Thermal Runaway Propagation. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2024, 91, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Duan, Q.L.; Xu, J.J.; Chen, H.D.; Lu, W.; Wang, Q.S. Experimental Study on the Efficiency of Dodecafluoro-2-Methylpentan-3-One on Suppressing Lithium-Ion Battery Fires. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 42223–42232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ye, F.M.; Li, Y.Q.; Chen, M.; Meng, X.D.; Xu, J.J.; Sun, J.H.; Wang, Q.S. Experimental Study on the Efficiency of Dodecafluoro-2-Methylpentan-3-One on Suppressing Large-Scale Battery Module Fire. Fire Technol. 2023, 59, 1247–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, A.O.; Stoliarov, S. Analysis of Effectiveness of Suppression of Lithium Ion Battery Fires with A Clean Agent. Fire Saf. J. 2021, 121, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, C.X.; Huang, Q.R.; Li, S.Y.; Huang, J.H.; Ni, X.M.; Wang, J. Investigation on the Temperature Variation of Novec-1230 and Halon 1301 in A Discharge System. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 50, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tian, S.; Xiao, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, D. Insight into the Decomposition Mechanism of C6F12O-CO2 Gas Mixture. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 360, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Gao, W.; Chen, L.R.; Li, Y.C. Inhibition and Enhancement of Hydrogen Explosion by Perfluorohexanone. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 53, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, G.; Jia, H.; Dong, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H. Enhancing Atomization and Fire-Suppression Efficiency of Perfluorohexanone Using Swirl Nozzles Across A Range of Injection Pressures. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2026, 99, 105802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F.; Katta, V.R.; Babushok, V.; Linteris, G.T. Numerical and experimental studies of extinguishment of cup-burner flames by C6F12O. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2021, 38, 4645–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14520-1:2023(en); Gaseous Fire-Extinguishing Systems—Physical Properties and System Design — Part 1: General Requirements. The International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Chen, Y.; Fang, J.; Zhang, X.; Miao, Y.; Lin, Y.; Tu, R.; Hu, L. Pool Fire Dynamics: Principles, Models and Recent Advances. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2023, 95, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. Study on Fire Model Test and Numerical Simulation of Combustion Temperature Distribution and Smoke Concentration in High Altitude Tunnel. Master’s Thesis, Sichuan Agricultural University, Yaan, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z. Effects of Low AmbientPressure on Pool Fire Behaviorand Plume Characteristics. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. Study on the Relationship between Discharge Conditions and Class B Flame-extinguishing Effeet of Ce-Fluoroke tone. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Science & Technology, Nanjing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tuo, Y.; Huo, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhou, X. Effect of Low Ambient Pressure on Spray Characteristics of Water Mist and Effectiveness of Fire Extinguishing. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 283, 128976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Yang, R.; Zhang, H.; Ren, C.; Yang, J. Investigation of the Effect of Low Pressure on Fire Hazard in Cargo Compartment. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 158, 113775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.H.; He, Y.P.; Zhou, Z.H.; Yao, W.; Yuen, R.; Wang, J. The Burning Behaviors of Pool Fire Flames Under Low Pressure. Fire Mater. 2016, 40, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Cong, H.; Shao, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, K.; Bi, M.; Wang, X. Experimental and Theoretical Research on the Inhibition Performance of Ethanol Gasoline/Air Explosion by C6F12O. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2023, 83, 105088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.M.; Cong, H.Y.; Yuan, Z.Q.; Bi, Y.B.; Bi, M.S. Study on the Inhibitory Effect and Mechanism of Perfluoro (2-Methyl-3-Pentanone) on the Combustion of Gasoline Blended with Biomass Additives. Fuel 2023, 349, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extinguishing Agent | ODP | GWP | ALT (Years) | NOAEL (%) | LOAEL (%) | Ext. Conc. (v/v%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halon | 1.000 | 6500.000 | 65.000 | 0.100 | 0.050 | 4.500–5.900 |

| HFC-227ea | 0.000 | 3220.000 | 33.000 | 0.100 | 0.050 | 7.000–9.000 |

| CO2 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 3.000 | 34.000–40.000 |

| IG-541 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 5.000 | 3.000 | 34.000–40.000 |

| HFC-125 | 0.000 | 3500.000 | 29.000 | 0.500 | 0.200 | 5.000–6.000 |

| 2-BTP | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.050 | 0.100 | 0.050 | 6.000–9.000 |

| Perfluorohexanone | 0.000 | 1.000 | 5.000 | 0.500 | 0.200 | 4.500–5.900 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Chemical name | Difluoro(trifluoromethyl)oxymethyl-trifluoromethane |

| Molecular formula | C6F12O |

| Molecular weight (g/mol) | 316.040 |

| Appearance | Colorless transparent liquid |

| Gas density (kg/m3, 1 atm, 25 °C) | 13.600 |

| Liquid density (kg/m3, 25 °C) | 1610.000 |

| Boiling point (°C) | 49.200 |

| Freezing point (°C) | –108.000 |

| Heat of vaporization (kJ/kg) | 88.000 |

| Specific heat capacity (J/g·K, 25 °C) | 1.040 |

| Solubility | Slightly soluble in water; soluble in alcohols/ethers |

| Ozone depletion potential (ODP) | 0.000 |

| Global warming potential (GWP) | 1.000 |

| Atmospheric lifetime (days) | 5.000 |

| Extinguishing concentration (NFPA 2001, v/v%) | 4.500–5.900 |

| Dielectric strength (kV/cm) | 50.000 |

| Vapor pressure (kPa, 25 °C) | 39.900 |

| Environmental Pressure (kPa) | Oil Pan Size (cm) | Mass Loss Rate (g/s) | Heat of Combustion (kJ/g) | Combustion Efficiency (%) | HRR (kW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal pressure | 10 × 10 × 10 (A) | 0.093 | 44.600 | 0.830 | 3.442 |

| Normal pressure | 15 × 15 × 10 (B) | 0.229 | 44.600 | 0.830 | 8.477 |

| Normal pressure | 20 × 20 × 10 (C) | 0.632 | 44.600 | 0.830 | 23.395 |

| Low pressure | 10 × 10 × 10 (A) | 0.085 | 44.600 | 0.870 | 3.071 |

| Low pressure | 15 × 15 × 10 (B) | 0.201 | 44.600 | 0.870 | 7.78 |

| Low pressure | 20 × 20 × 10 (C) | 0.375 | 44.600 | 0.870 | 14.55 |

| Ambient Pressure | Mass Required for Pan A (kg) | Mass Required for Pan B (kg) | Mass Required for Pan C (kg) |

| Atmospheric | 0.402 | 0.652 | 0.770 |

| Low pressure | 0.178 | 0.125 | 0.094 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Q.; Yang, R.; Zhu, P. Study on the Effectiveness of Perfluorohexanone in Extinguishing Small-Scale Pool Fires in Enclosed Compartments Under Low-Pressure Conditions. Fire 2025, 8, 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120472

Liu Q, Yang R, Zhu P. Study on the Effectiveness of Perfluorohexanone in Extinguishing Small-Scale Pool Fires in Enclosed Compartments Under Low-Pressure Conditions. Fire. 2025; 8(12):472. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120472

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Quanyi, Ruxuan Yang, and Pei Zhu. 2025. "Study on the Effectiveness of Perfluorohexanone in Extinguishing Small-Scale Pool Fires in Enclosed Compartments Under Low-Pressure Conditions" Fire 8, no. 12: 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120472

APA StyleLiu, Q., Yang, R., & Zhu, P. (2025). Study on the Effectiveness of Perfluorohexanone in Extinguishing Small-Scale Pool Fires in Enclosed Compartments Under Low-Pressure Conditions. Fire, 8(12), 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120472