1. Introduction

China possesses abundant mineral resources, with coal serving as the backbone of its energy structure and playing a pivotal role in industrial production and national energy security. By the end of 2023, the country’s proven coal reserves had reached 218.57 billion tons [

1], and raw coal production reached 4.78 billion tons in 2024, accounting for over 50% of global coal output. However, coal fires have emerged as a significant challenge in the exploitation and utilization of coal resources, particularly in coal-rich regions such as Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and Ningxia [

2]. For instance, the total coal fire-affected zone in Xinjiang alone has reached approximately 10.31 million square meters, resulting in an annual loss of nearly 21.8 million tons of coal resources.

Coal fires not only lead to substantial resource loss but also exacerbate surface subsidence, ecological degradation, and air pollution, posing serious threats to mining safety and regional environmental stability [

3,

4]. UAV-based thermal infrared remote sensing has emerged as a crucial technology for coal fire detection and early warning due to its real-time monitoring capability, high spatial resolution, non-contact operation, and extensive coverage [

5]. In recent years, 3D reconstruction techniques leveraging UAV-acquired remote sensing data have gained momentum. These methods not only reconstruct the topographic structure of coal fire zones but also enable spatial analysis of temperature distribution using TIR data, thereby enhancing the accuracy of fire monitoring and trend prediction [

6,

7,

8]. However, in practical applications, several factors, including variations in UAV flight altitude and attitude, atmospheric disturbances (e.g., aerosol scattering, water vapor absorption), sensor noise, and complex terrain effects, can introduce systematic and random errors into thermal imaging, significantly compromising temperature measurement accuracy and impairing the reliable identification of coal fire zones. Therefore, improving the accuracy of thermal infrared temperature retrieval and integrating corrected TIR imagery with 3D reconstruction to generate high-fidelity 3D thermal fields for coal fire zones has become a critical focus in current coal fire prevention and control research.

In recent years, various methodologies have been developed to improve the temperature measurement accuracy of TIR images, including radiometric correction models, atmospheric compensation algorithms, and data-driven approaches. R Usamentiaga et al. [

9] utilized convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to detect and track thermal targets, eliminating reliance on unreliable GPS coordinates. Alexa et al. [

10] proposed an improved surface temperature measurement method for glossy materials, thereby enhancing the accuracy of TIR imagers. Li et al. [

11] developed a precise infrared array imaging system using the MLX90640 sensor (Melexis Technologies NV, Tessenderlo, Belgium), integrating a modified least squares curve-fitting model for temperature compensation. Cai et al. [

12] introduced a blackbody-free infrared temperature correction method based on Newton’s Law of Cooling to address temperature drift under varying environmental conditions, enabling real-time compensation. Wei [

13] et al. proposed a compensation model considering different emissivity conditions, effectively correcting measured temperatures of heterogeneous targets. Yang et al. [

14] combined separable convolutional neural networks (SCNNs) with long short-term memory (LSTM) networks to build an SCNN-LSTM model for lake temperature prediction using only thermal inputs, improving the predictive accuracy of TIR data. While physical model-based approaches—such as radiative transfer and atmospheric compensation models—rely heavily on precise parameterization (e.g., atmospheric transmittance, emissivity, and path radiance), acquiring accurate parameters in complex field environments remains challenging. Moreover, these models are computationally demanding and often lack flexibility in adapting to dynamically changing conditions. On the other hand, empirical formulas, though simple and easy to implement, fail to capture the nonlinear interactions among multiple influencing factors and demonstrate poor generalizability beyond the specific scenarios for which they were developed. Machine learning techniques, such as Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Random Forest (RF), have shown potential in modeling nonlinear relationships; however, they still encounter difficulties related to hyperparameter tuning, vulnerability to local optima, and reduced robustness under highly variable environmental conditions [

15,

16].

In the domain of thermal infrared 3D reconstruction, S. Wasilewski et al. [

17] employed UAV-based thermal imaging to derive two-dimensional surface temperature distributions in coal fire zones and applied a moving window algorithm to extract thermal anomalies. Abramowicz, A et al. [

18] utilized UAVs equipped with thermal infrared sensors and 2D surface temperature models to evaluate the environmental impact of spontaneous combustion at the So Pedro da Cova coal waste site. Wang et al. [

19] generated 2D thermal field maps of the Datong coalfield using drone-mounted thermal cameras. At the same time, Yuan et al. [

20] assessed the environmental impact of coal gangue heap fires through UAVs carrying both thermal infrared and multispectral sensors, generating digital elevation models (DEMs) and surface temperature profiles. Additionally, He et al. [

21] integrated ground surveys with UAV-mounted thermal infrared cameras to delineate the fire-affected zones of the Huojitu coal mine in Shenmu. Overall, current research predominantly focuses on thermal orthophoto projections or the overlay of 2D TIR imagery onto 3D terrain models, resulting in pseudo-3D (texture mapping on 3D terrain) thermal field representations [

22,

23]. In our prior work, we pursued the goal of generating a true 3D thermal field (where temperature is an inherent vertex attribute) by implementing a pipeline that enhanced the success rate of TIR image-based 3D reconstruction. This was achieved through batch preprocessing (standardizing temperature ranges, distribution patterns, and color scales across all images) in conjunction with feature point matching and texture mapping techniques [

24,

25,

26]. However, these methods fall short in capturing surface temperature with high fidelity. Although UAV-based TIR imaging has seen notable progress, the precise reconstruction of 3D surface thermal fields in coal fire zones remains underexplored, and the practical realization of high-fidelity 3D thermal models has yet to be achieved.

To bridge these critical gaps, this study aims to develop an integrated NRBO-XGBoost framework for high-fidelity temperature correction and true 3D thermal field reconstruction in coal fire zones. The work is necessary to move beyond the limitations of current pseudo-3D representations and empirically driven corrections. Our primary objectives are threefold: (1) to propose and validate the NRBO-XGBoost model that leverages second-order optimization to achieve superior correction accuracy and robustness over conventional methods; (2) to integrate the corrected thermal data into a 3D reconstruction pipeline, establishing a true 3D thermal field where temperature is an intrinsic geometric attribute rather than a surface texture; and (3) to demonstrate the practical necessity and efficacy of the entire framework through a comprehensive field application, thereby providing a reliable technical solution for accurate coal fire monitoring and mitigation.

3. Experiment Design and Dataset Construction

3.1. Experiment Design

This study utilizes the DJI Matrice 210 RTK V2 (DJI, Shenzhen, China) quadcopter, equipped with the DJI Zenmuse XT2 (DJI, Shenzhen, China) dual-camera system. The infrared imaging module features a FLIR Tau 2 thermal sensor (640 × 512 pixels, temperature range: −40 °C to 550 °C), while the visible-light module contains a 12-megapixel optical sensor. The experimental monitoring target is an infrared microcrystalline constant-temperature electric heating plate (400 × 600 mm) capable of maintaining a uniform surface temperature. Its temperature is precisely controllable within a specified range (from ambient temperature to 600 °C), with an accuracy of ±1 °C, enabling the simulation of realistic coal fire conditions. To further ensure data quality, the heating plate was allowed to stabilize for at least 20 min at each target temperature before data acquisition commenced. Additionally, spot checks were periodically performed using a calibrated K-type thermocouple (with an accuracy of ±0.5 °C) to verify the surface temperature readings, which consistently confirmed the stability and accuracy of the heating plate.

The experimental design covers multiple seasons and meteorological conditions, including sunny, cloudy, and day/night cycles, to comprehensively evaluate the influence of external environmental factors on UAV-based thermal infrared measurements. An orthogonal experimental design is adopted, with temperature settings ranging from 5 °C to 500 °C. Multiple flight altitudes are set from 0 to 120 m in 5 m intervals to simulate variations in observational scale. After hovering at each altitude, the UAV collects data to ensure spatial consistency and measurement repeatability. The experimental procedure is illustrated in

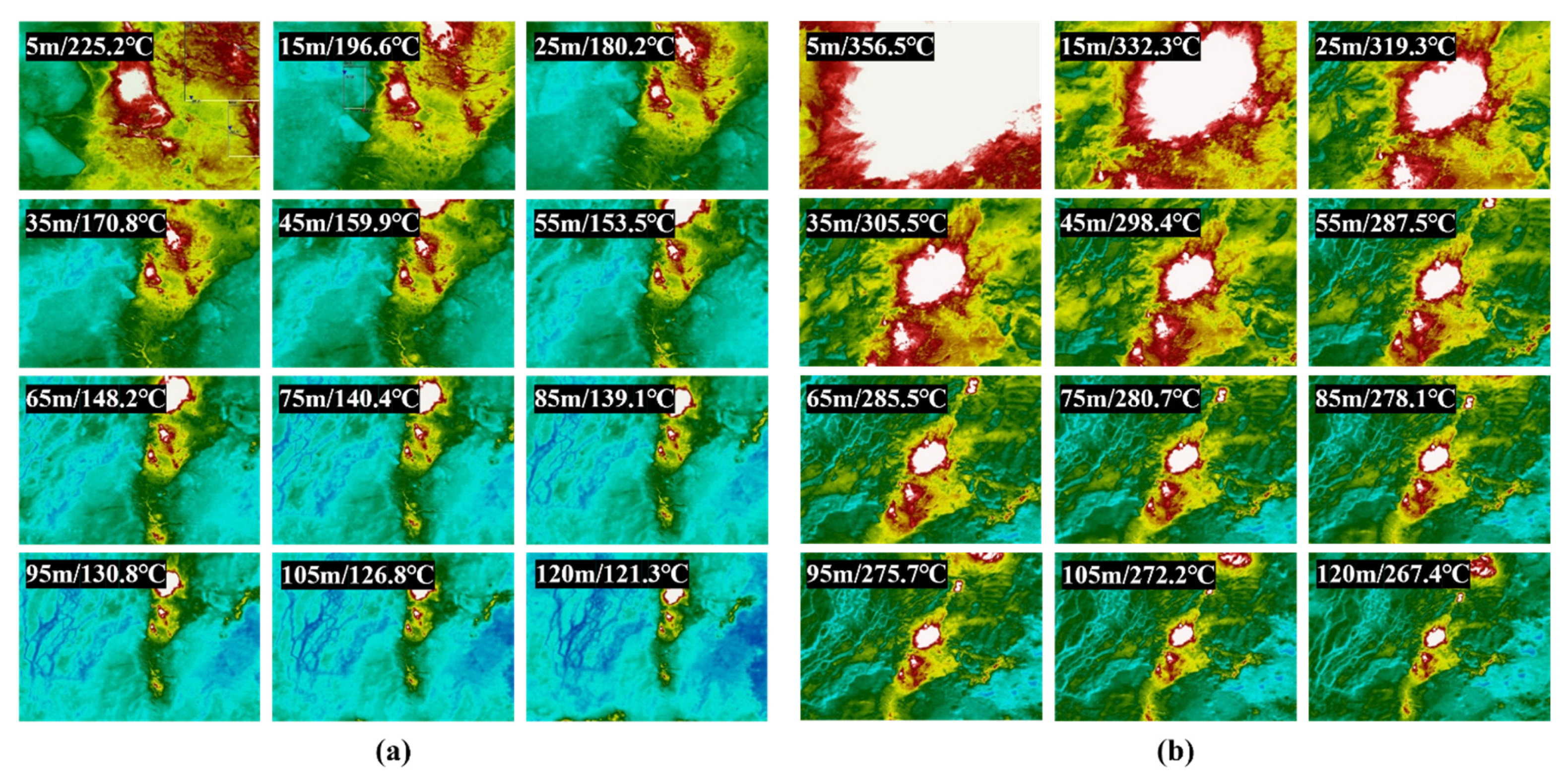

Figure 1, and sample TIR images are shown in

Figure 2.

The data acquisition process includes three components:

Multi-altitude infrared temperature measurements: The UAV collects thermal data of the heating plate at various altitudes;

Observation coverage and time scheduling: To ensure data representativeness, measurements are conducted across multiple periods (morning, afternoon, and night) to examine diurnal temperature effects. At each altitude, repeated measurements are performed to capture stable readings under dynamic thermal conditions;

Environmental parameter monitoring: Atmospheric temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed are concurrently recorded using professional instruments (e.g., thermometers, hygrometers, electronic anemometers) to ensure a comprehensive environmental dataset.

Figure 1.

Experiment on remote sensing data acquisition by the UAV.

Figure 1.

Experiment on remote sensing data acquisition by the UAV.

Figure 2.

Examples of TIR image sequences acquired from experiments. (a) Partial TIR images at 468.6 °C from 5 to 120 m altitude. (b) Partial TIR images at 200.6 °C from 5 to 120 m altitude.

Figure 2.

Examples of TIR image sequences acquired from experiments. (a) Partial TIR images at 468.6 °C from 5 to 120 m altitude. (b) Partial TIR images at 200.6 °C from 5 to 120 m altitude.

3.2. Dataset Construction and Analysis

This study is grounded in experimental data collected via UAV-based remote sensing over the past year. The data acquisition campaign encompasses a wide range of thermal conditions (5–500 °C), varying UAV flight altitudes (0–120 m, sampled at 5 m intervals), and different seasonal environments (spring, summer, autumn, and winter), aiming to comprehensively capture thermal infrared monitoring scenarios alongside relevant meteorological variables.

Through a systematic experimental design and standardized data collection protocol, a six-dimensional feature dataset comprising 3800 samples is constructed. The input features include thermal infrared monitoring temperature, UAV flight altitude, ambient temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed. The output variable is the actual surface temperature of the constant-temperature heating plate, which serves as the reference for model correction.

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution patterns and fluctuation ranges of each input feature.

By analyzing histograms and box plots (The orange region represents the data distribution between the 25th percentile (Q1) and the 75th percentile (Q3), corresponding to the middle 50% of the dataset), it is evident that each input feature exhibits distinct distribution characteristics, highlighting the complexity of thermal infrared monitoring in coal fire environments. Specifically, the monitoring temperature (monitoring_temp) follows an approximately normal distribution with slight right skewness. Ambient temperature (ambient_temp) and relative humidity (humidity) display multi-modal patterns, while wind speed (wind_speed) is heavily right-skewed and contains numerous outliers. In contrast, UAV flight altitude (altitude) is uniformly distributed, ensuring data balance across different altitudes in line with the experimental design. A detailed statistical analysis of each input feature is summarized as follows:

Values primarily range from 90 °C to 230 °C and follow an approximately normal distribution with mild right skewness (Skewness = 0.225). While surface temperatures typically exhibit a Gaussian distribution, underground coal combustion causes persistent localized heating, producing long-tailed distributions. This skewness reflects the physical manifestation of thermal anomalies in coal fire zones and suggests increased uncertainty in high-temperature thermal infrared measurements.

Ranging from 16 °C to 28 °C, this feature shows a multi-modal distribution, capturing varying meteorological conditions such as diurnal cycles and seasonal transitions. Since thermal infrared measurements are sensitive to ambient temperature, this diversity ensures the dataset’s representativeness under a broad range of environmental conditions.

Also demonstrating a multi-modal distribution (35.8–53.0%), this feature indicates the inclusion of diverse humidity scenarios. Atmospheric water vapor influences infrared signal absorption and scattering; thus, humidity serves as an essential input for improving the generalization of the temperature correction model.

The distribution is markedly right-skewed, with most data clustered between 0 and 1.5 m/s, while a few values exceed 4 m/s and are identified as outliers (above 1.5× the interquartile range). Strong wind conditions enhance convective heat transfer, destabilize surface temperature fields, and increase the scattering of ground-emitted thermal radiation, thereby introducing measurement biases. Wind speed is therefore treated as a disturbance factor in the model, and robust optimization strategies, such as outlier handling or non-linear regression, are applied to mitigate its impact.

This feature is uniformly sampled across a range of 0–120 m (in 5 m intervals), consistent with orthogonal experimental design principles. This uniformity enables the analysis of altitude effects on thermal infrared measurement accuracy and supports model generalizability. Variations in altitude affect image spatial resolution and may lead to thermal signal attenuation due to atmospheric absorption and scattering. A balanced distribution of altitude data enhances the robustness and wide applicability of the correction model.

4. NRBO-XGBoost Model Training and Result Validation

The NRBO-XGBoost regression model proposed in this study, which integrates the NRBO and XGBoost, comprises three main stages: data processing, model training, and temperature prediction (as shown in

Figure 4). The specific tasks are as follows:

First, the six-dimensional feature dataset is systematically organized. By incorporating domain knowledge and statistical rules, abnormal data are manually screened and adjusted to enhance data integrity and consistency. To improve data quality, raw data undergo cleaning and augmentation, including missing value imputation and outlier removal. Additionally, feature standardization (Scaler Normalization) is applied to eliminate scale differences among variables, ensuring stability and generalization capability during model training.

The dataset is partitioned into training and test sets at an 8:2 ratio, with initial hyperparameters defined. During model training, the NRBO algorithm is employed for hyperparameter optimization. By leveraging gradient calculations and second-order derivative information from the Hessian matrix, NRBO accelerates the hyperparameter optimization process and reduces the risk of converging to local optima [

33,

34,

35]. Compared to traditional methods such as Grid Search or Bayesian Optimization, NRBO effectively narrows the hyperparameter search space and improves training efficiency.

Based on the dataset scale and feature relationships, key hyperparameters are optimized, including n_estimators (number of weak classifiers), max_depth (maximum tree depth), learning_rate (learning rate), subsample (subsampling rate), and gamma (minimum loss reduction). Furthermore, K-fold cross-validation is adopted to evaluate model generalization capability, with RMSE and the coefficient of determination (R

2) as performance metrics [

36]. If the model fails to meet predefined convergence criteria, hyperparameters are iteratively adjusted until optimal correction accuracy is achieved. The optimized XGBoost model and its weight parameters are stored in JSON format for subsequent prediction tasks.

During the prediction phase, coal fire monitoring temperature data are extracted from TIR images, and CSV-formatted data matrices are read. A visual interactive interface is provided to dynamically input additional feature variables, enhancing prediction flexibility. All input features are standardized and converted into DMatrix format to align with the XGBoost modeling pipeline. Finally, the model generates corrected coal fire temperatures, which are reshaped into coordinate layouts consistent with the original CSV temperature matrix. This ensures spatial alignment between the predicted temperature field and TIR image data, providing robust data support for subsequent 3D thermal field reconstruction.

Figure 4.

Modeling pipeline of the NRBO-XGBoost temperature correction model.

Figure 4.

Modeling pipeline of the NRBO-XGBoost temperature correction model.

4.1. Comparison of Baseline Models and Optimizers

In the field of machine learning, the selection of an appropriate regression model plays a critical role in improving predictive accuracy. To identify the most suitable regression approach for this study, five widely used regression algorithms were comparatively evaluated: Linear Regression, Ridge Regression, Random Forest Regression, LightGBM Regression, and XGBoost. All models were trained on the same dataset and evaluated using an independent test set.

Two performance metrics were employed to assess the models: the coefficient of R

2 and the normalized RMSE. While R

2 quantifies the goodness of fit, the normalized RMSE reflects the magnitude of prediction errors.

Figure 5 presents a comparative analysis of the five regression models in terms of these two metrics. The results demonstrate that XGBoost outperforms the other models on both R

2 and RMSE metrics.

As shown in

Figure 5, the XGBoost model achieves the highest R

2 value of 0.9371, indicating superior fitting capability and a stronger ability to capture underlying patterns in the data. Additionally, its normalized RMSE reaches 0.1042, representing a significant reduction in prediction error compared to the other models. Owing to its remarkable performance in both fitting accuracy and error minimization, XGBoost was ultimately selected as the regression model for this study.

To justify the selection of the Newton–Raphson-Based Optimizer (NRBO), a systematic comparison was conducted against several established hyperparameter optimization techniques, including Grid Search, Bayesian Optimization (BO), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO). Qualitatively, Grid Search guarantees global optimization but becomes computationally prohibitive in high-dimensional spaces. Bayesian Optimization, while sample-efficient, incurs significant overhead in training surrogate models within complex, high-dimensional landscapes and often exhibits limited global exploration. Swarm intelligence algorithms such as PSO and GWO demonstrate competent global search capabilities yet are prone to premature convergence, slow convergence rates, and instability across runs. In contrast, NRBO incorporates a Newton–Raphson-inspired search rule that leverages second-order derivative information to accelerate convergence and refine search direction. Coupled with a trap avoidance operator, it effectively preserves population diversity, thereby achieving a more effective balance between global exploration and local exploitation. Quantitative assessments further confirm NRBO’s superior performance (as shown in

Table 1): in tuning XGBoost hyperparameters, it attained the lowest RMSE (3.05), required the fewest iterations to converge, and exhibited the highest stability over repeated trials. These findings underscore the unique advantages of NRBO in addressing high-dimensional, non-convex hyperparameter optimization problems, establishing it as a critical enabler of highly accurate temperature correction in this study.

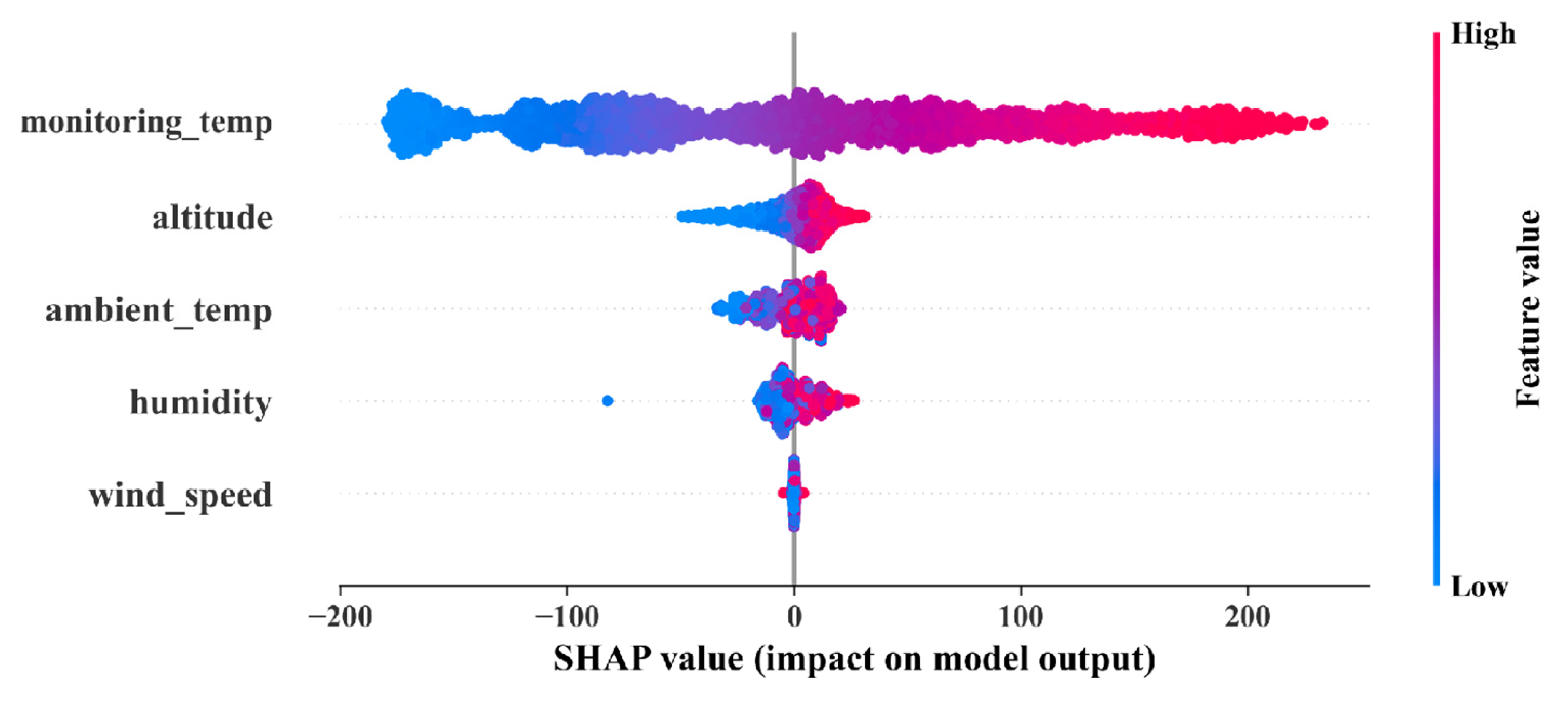

4.2. Feature Importance Analysis via SHAP

In this study, the SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) approach was employed to analyze the feature importance of the selected regression model [

37]. SHAP values effectively reveal the contribution of each input feature to the model’s predictions, thereby providing a deeper understanding of the model’s decision-making process [

38].

Figure 6 illustrates a comparative overview of feature effects and their importance as determined by the SHAP analysis.

The analysis indicates that the thermal infrared monitoring temperature (monitoring_temp) is the most influential feature affecting the model output. Its SHAP value increases markedly with higher monitoring temperature values, suggesting a strong positive correlation between the observed temperature and the predicted outcome.

The UAV flight altitude (altitude) also exerts a substantial impact on the model’s predictions. Notably, at higher altitudes, the SHAP values exhibit a negative shift, indicating a negative correlation between altitude and predicted temperature. This phenomenon may be attributed to variations in the sensor’s viewing angle and temperature distribution caused by changes in flight elevation, which in turn affect the estimation of thermal information from infrared imagery. Furthermore, the individual feature importance analysis suggests a potential nonlinear interaction between monitoring temperature and altitude. It is physically plausible that the correction model learns to apply a stronger negative bias to the raw temperature reading when a high value is observed from a greater altitude, due to the increased atmospheric path length and attenuation. A quantitative investigation of this specific interaction represents a valuable direction for future research.

The ambient temperature (ambient_temp) is another significant factor. As the environmental temperature rises, the corresponding SHAP values increase substantially, suggesting that changes in external atmospheric temperature directly influence the correction of temperature estimations in TIR imagery.

In contrast, relative humidity (humidity) and wind speed (wind_speed) show limited impact on model predictions. Their SHAP values are narrowly distributed, with relatively weak correlations to the output. This indicates that these meteorological factors contribute minimally to temperature prediction under normal conditions and may only play a role under extreme environmental circumstances.

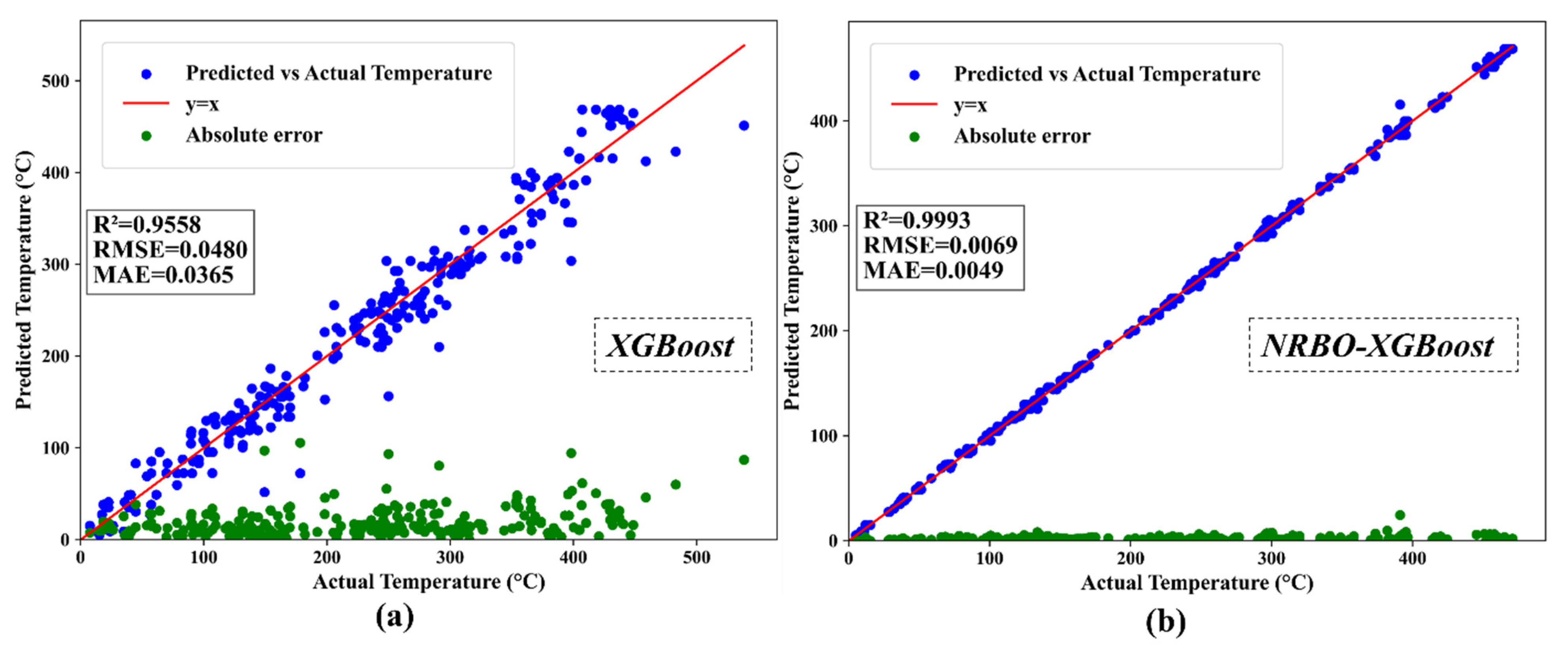

4.3. Quantitative Validation

To evaluate the generalization capability of the proposed NRBO-XGBoost model in temperature prediction tasks, an independent test set comprising 264 samples of six-dimensional feature data collected from an actual coal fire zone was utilized, where the ground truth (actual_temp) was directly measured by a calibrated K-type thermocouple (with an accuracy of ±0.5 °C). The corresponding TIR image sequences are shown in

Figure 7. The test data spans a wide range of temperature levels and includes complex environmental conditions to ensure the model’s adaptability under realistic coal fire scenarios.

A comparative analysis was conducted between the NRBO-XGBoost model and the original XGBoost model. As illustrated in

Figure 8, the NRBO-XGBoost model demonstrates notable improvements in terms of fitting accuracy, error control, and prediction stability, particularly in high-temperature regions.

The comparative results indicate that the NRBO-XGBoost model significantly improves both the accuracy and stability of temperature prediction compared to the original XGBoost model. Specifically, after hyperparameter optimization using NRBO, the coefficient of determination (R2) increased to 0.9993, compared to 0.9558 achieved by the original XGBoost, suggesting a substantial enhancement in model fitting capability and explanatory power for actual temperature values. The potential for model overfitting was proactively addressed through a multi-faceted strategy. A cardinal step was employing K-fold cross-validation during training and rigorous evaluation on a fully independent test set of 264 field samples from coal-fire areas, ensuring exposure to unseen, real-world conditions. The model’s inherent robustness is further fortified by the extensive dataset (3800 samples) and the regularization mechanisms within XGBoost. Specifically, the NRBO algorithm optimized the L2 regularization parameter (λ) and the minimum loss reduction (γ), thereby actively constraining model complexity and guaranteeing robust predictive performance on new data. Moreover, the root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) were reduced by 85.6% and 86.6%, respectively, indicating a marked decrease in prediction uncertainty. Notably, the NRBO-XGBoost model exhibited significant performance improvements in high-temperature regions (>300 °C), with more uniform error distributions, thereby avoiding the error accumulation observed in the original model under extreme thermal conditions. These findings strongly validate the effectiveness of the NRBO optimization algorithm in enhancing the regression performance of XGBoost, resulting in improved prediction accuracy and robustness under complex coal fire scenarios.

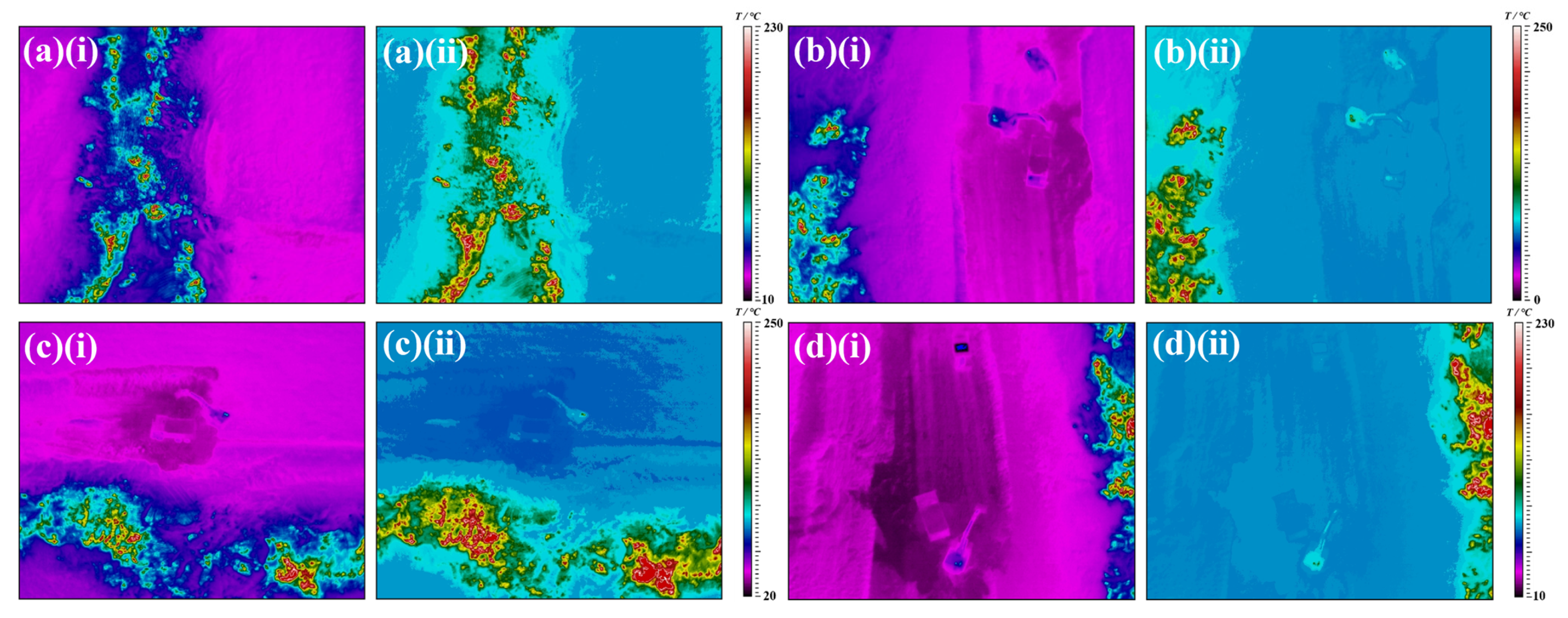

4.4. Visual Validation

To comprehensively evaluate and validate the effectiveness of the NRBO-XGBoost model in coal fire monitoring, this study compares the original TIR images with the corresponding temperature-corrected versions. The aim is to assess the model’s ability to enhance temperature correction accuracy and improve the spatial representation of high-temperature regions. To clearly illustrate this difference and intuitively validate the correction effect, a set of comparative images was generated, as shown in

Figure 9, displaying TIR images before and after correction.

The comparative analysis reveals that the corrected images exhibit significant improvements in high-temperature region recovery, boundary clarity, and spatial continuity. These improvements provide further evidence of the model’s effectiveness in accurate coal fire delineation and thermal anomaly detection.

For instance, in

Figure 9a, the original TIR image presents a narrow temperature range (30.5–268.8 °C), with relatively low background temperatures (represented by purple regions). This results in an underestimation of certain high-temperature regions, leading to fragmented thermal patterns and unclear fire boundaries. Statistical analysis shows that in the original image, high-temperature regions (T > 150 °C) only account for 18.6% of the coal fire zone, with some regions failing to be identified due to low thermal values.

After correction with the NRBO-XGBoost model, the temperature range expands significantly to 51.2–345.3 °C, and the background temperature is adjusted to more realistic levels (depicted in blue). The gradient and continuity of high-temperature regions become more distinct and coherent, allowing for a more accurate thermal representation of the fire-affected region. Consequently, the proportion of high-temperature regions increases to 37.4%, representing a 101% improvement compared to the pre-correction state. This substantially enhances the completeness of thermal region delineation and sharpens the fire boundary definition. Furthermore, the average temperature within high-temperature regions rises from 132.4 °C to 198.6 °C, effectively mitigating the underestimation issue inherent in the original TIR images.

Both quantitative indicators and visual inspection confirm that the corrected TIR images more accurately reflect the actual temperature distribution within coal fire zones. The enhanced visibility of high-temperature regions reduces measurement errors caused by environmental complexity and highlights thermal anomalies more effectively. This optimization not only improves the consistency and reliability of temperature data but also increases the model’s adaptability to varying environmental conditions, thereby providing more accurate and robust support for coal fire monitoring.

5. Field Application

5.1. Overview of the Santanghu Coal Fire Zone, Hami, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China

The Santanghu mining area in Hami City is located in the northeastern direction (18°) of Balikun Kazakh Autonomous County, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China, approximately 84 km northeast in a straight line. The coal fire zone is situated within the No. 3 mining block of the Tiaohu coalfield. In the eastern part of the mining area, historical unauthorized excavation of humic acid has led to complete surface stripping, resulting in extensive exposure of coal seams. This exposure has caused spontaneous combustion along outcrops and the development of large-scale coal fires. In the western section, illegal small-scale coal mining has resulted in the formation of multiple surface subsidence regions. These subsided regions have created oxygen supply channels, and subsurface temperature anomalies have been detected through field surveys.

The spontaneous combustion of coal seams in this area is primarily triggered by surface excavation, which exposes the coal seams to prolonged oxidation. Additionally, earlier underground mining activities with poorly sealed shafts have led to ground collapse and fissure formation. These geological features act as ventilation pathways, enabling the combustion of residual coal in deep goafs. The coal fire zone exhibits visible surface flames and manifests a belt-shaped distribution pattern, accompanied by elongated ground collapses. Burnt brick-red altered rocks, characteristic of combustion metamorphism, are also observable, as shown in

Figure 10. The fire has been active for an extended period, leading to severe coal resource depletion and the formation of numerous high-temperature pits, cracks, and fragmented zones at the surface. With the continuous expansion of the combustion front, coal resource losses are still increasing annually. It is estimated that the annual coal resource loss in this coal fire zone amounts to 925,892.25 tons. Urgent and targeted coal fire zone detection is therefore required to support subsequent firefighting and mitigation strategies.

5.2. TIR Data Collection and Correction

Thermal infrared remote sensing data for the coal fire zone were collected using the DJI Matrice 210 RTK V2 (DJI, Shenzhen, China) quadrotor UAV, identical to the platform used in the experiments. The UAV was equipped with a DJI Zenmuse XT2 dual-sensor camera. According to the standard procedures of oblique photogrammetry, five flight routes were planned, including four oblique photography paths and one nadir path, to acquire multi-perspective TIR image sequences. The UAV was flown at an altitude of 100 m, with a horizontal speed of 5 m/s. The side overlap and forward overlap rates were set to 70% and 80%, respectively. A total of 1045 visible images and 1045 TIR images were acquired, along with synchronized meteorological measurements of the zone.

After data collection, the coal fire monitoring temperature was extracted from each TIR image and stored as a CSV-formatted temperature matrix (640 columns × 512 rows), facilitating input to the NRBO-XGBoost model. The NRBO-XGBoost model applied in this section is the same one whose predictive accuracy was quantitatively validated in

Section 4.3 using an independent test set from an actual coal fire area, where the ground (actual_temp) truth was directly measured by a calibrated K-type thermocouple (with an accuracy of ±0.5 °C). A dynamic visualization interface was employed to input recorded meteorological variables as feature data. All features were normalized and subsequently transformed into the DMatrix format required by the NRBO-XGBoost modeling framework. The model then generated corrected coal fire temperature values, which were reshaped into the same coordinate structure as the original temperature matrices. Finally, the corrected CSV matrices were converted into image formats suitable for 3D reconstruction, ensuring accurate thermal mapping.

Figure 11 illustrates the extracted thermal hotspot contours before and after correction for two representative scenes in the Santanghu coal fire zone.

Spatial thermal hotspot analysis based on pre- and post-correction TIR images demonstrates the superior performance of the proposed NRBO-XGBoost model in identifying high-temperature regions, restoring hotspot morphology, and improving spatial coverage.

For example, in

Figure 11a, only 40 high-temperature thermal hotspots (≥150 °C) are detected in the original image, with an average area of 0.2104 m

2, a maximum area of 1.9791 m

2, and a total coverage of 8.4157 m

2. These thermal hotspots exhibit sparse distribution, poorly defined boundaries, and spatial isolation, rendering them inadequate for the accurate delineation of coal fire zones.

In contrast, the corrected image identifies 159 high-temperature thermal hotspots (a 297.5% increase). The average hotspot area increases to 0.6508 m2 (a 309.6% increase), while the maximum area expands dramatically to 33.7228 m2, representing a 1700.5% improvement. The total high-temperature coverage reaches 103.7516 m2, approximately 12 times that of the original image. Additionally, the spatial configuration of thermal hotspots shifts from fragmented and dispersed patches to more continuous, banded, and clustered structures. The contours appear clearer and more enclosed, improving shape fidelity.

Furthermore, the corrected images exhibit increased thermal density. In the original image, high-temperature regions are mainly concentrated along the right edge with a scattered distribution. After correction, hotspots are more extensively distributed along the main coal fire belt, showing significantly enhanced spatial clustering. In certain localized areas, the density of thermal hotspot regions increases by approximately 4.6 times, offering a more accurate representation of the core thermal structure of the coal fire.

5.3. 3D Thermal Field Reconstruction

To more comprehensively characterize the spatial thermal anomalies of subsurface coal fires, this study constructed a series of 3D thermal field models using a combination of 3D reconstruction and RGB-T feature fusion techniques. As shown in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, the models include: the original 3D thermal field reconstructed from raw TIR imagery, the true 3D thermal field corrected by the NRBO-XGBoost model, and the detail-enhanced thermal field obtained by fusing high-resolution RGB textures.

The original thermal field model (

Figure 12a) was reconstructed based on our previous methodology [

24,

25,

26], which primarily focused on improving the geometric success of 3D modeling from TIR sequences. This earlier pipeline involved batch preprocessing—standardizing temperature ranges, distribution patterns, and color maps across images—followed by feature matching and texture mapping. However, a key limitation of this approach was its reliance on the uncorrected, raw thermal values from the UAV sensor as the texture source. Consequently, while the model successfully reconstructs the 3D terrain, the mapped temperature distribution inherits the inaccuracies of the original imagery, leading to a severe underestimation of temperatures, fragmented thermal anomalies, and poor boundary definition. The fundamental advancement presented in this work is the integration of the high-fidelity temperature correction performed by the NRBO-XGBoost model prior to reconstruction. This critical step ensures that the 3D model is textured with physically accurate and spatially consistent temperatures, enabling the generation of a true high-fidelity 3D thermal field.

The corrected 3D thermal field model (

Figure 12b) significantly improves upon these limitations. By applying the NRBO-XGBoost regression correction, the temperature response range, particularly for high temperatures, is greatly expanded, even under a broader color scale. High-temperature regions (in red) exhibit clear strip-like patterns with strong spatial continuity, sharp boundaries, and smooth internal gradients. The model also effectively corrects previously underestimated low-temperature regions, producing a more physically realistic match with the actual thermal anomaly distribution in the coal fire zone.

The detail-enhanced model (

Figure 12c), which integrates high-resolution RGB textures, further improves the interpretability of the thermal field. While retaining the benefits of temperature correction, it introduces fine surface details and spatial semantic information through RGB-T fusion. This enhancement results in sharper thermal region boundaries and richer background structural context. Particularly in transitional zones, the color gradient transitions closely align with terrain contours, enhancing the model’s ability to depict thermal anomaly propagation paths.

As illustrated in

Figure 14 the corrected 3D thermal field model demonstrates a marked improvement in identifying high-temperature anomalies. In the original model, high-temperature regions account for only 0.43% of the total surface area, primarily appearing as isolated hotspots that fail to form continuous thermal belts. This significantly limits the accurate delineation of the coal fire boundary. In contrast, the corrected model increases the proportion of high-temperature areas to 2.60%, effectively expanding the detectable thermal anomaly range and mitigating omissions caused by temperature underestimation in the raw data.

Figure 15 presents a localized comparison between the corrected and detail-enhanced 3D thermal field models. In (i), although the corrected temperature field exhibits continuous high-temperature distributions, texture detail remains limited, particularly in low-temperature transitions and fine thermal gradients. In (ii), the RGB-T fusion introduces notable improvements in image clarity, edge sharpness, and structural fidelity. Enhanced textures, especially around object boundaries and high-temperature zones, provide a more accurate and interpretable thermal distribution. The integration of visible and thermal information enhances the model’s spatial precision and visualization quality, facilitating more accurate identification of heat sources and surrounding anomalies. This is particularly beneficial for analyzing coal fire expansion and predicting high-risk zones.

Through the complete optimization process proposed in this study, the 3D thermal field models progressively improve, from correcting underestimated temperatures to transforming fragmented thermal hotspots into coherent thermal belts, and ultimately clarifying coal fire boundaries and terrain textures. The final detail-enhanced model demonstrates strong potential for coal fire monitoring and early warning applications, validating the effectiveness and practical adaptability of the NRBO-XGBoost model in enhancing temperature representation in TIR imagery.

6. Conclusions

This study addresses the issue of measurement accuracy degradation in UAV-based thermal infrared remote sensing caused by environmental interference and systematic errors. A novel temperature correction model, NRBO-XGBoost, is proposed, integrating the Newton–Raphson-Based Optimizer (NRBO) algorithm with Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost). It is particularly suited for coal fire monitoring due to its direct alignment with the application’s core demands. The model excels in handling the high-dimensional, non-linear thermal data inherent to coal fires, thanks to the XGBoost component. Simultaneously, the NRBO optimization ensures robust performance under complex field conditions by achieving a globally optimal model configuration, a critical advantage over traditional optimizers. This dual strength enables the unprecedented accuracy and spatial coherence in thermal anomaly detection demonstrated in our field application. The corrected data are subsequently used to reconstruct a high-fidelity 3D thermal field through RGB-T feature fusion and 3D reconstruction techniques. The main conclusions are as follows:

A six-dimensional feature dataset is constructed, comprising 3800 samples. The input features include thermal monitoring temperature, UAV altitude, ambient temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed, while the actual temperature serves as the output variable. The dataset covers diverse conditions across temperature ranges (5–500 °C), UAV flight altitudes (0–120 m, at 5 m intervals), and all four seasons. Standardization and outlier handling strategies are employed to enhance the robustness and adaptability of the data-driven model under complex environmental conditions.

A thermal infrared temperature correction model, NRBO-XGBoost, is proposed by embedding second-order optimization information (Hessian matrix) into XGBoost via the NRBO algorithm. This approach accelerates convergence, mitigates local optima, and significantly improves prediction accuracy (R2 = 0.9993; RMSE reduced by 85.6%; MAE reduced by 86.6%), while enhancing the generalization capability of the model.

A 3D thermal field enhancement approach based on RGB-T feature fusion is employed to enable high-fidelity reconstruction of thermal fields in coal fire zones. By integrating the corrected 3D thermal field model with visible-spectrum texture features, a high-fidelity and detail-enhanced 3D thermal model is generated. This enables more continuous and precise localization of thermal anomalies.

In the field application conducted at the Santanghu coal fire zone in Xinjiang, the final detail-enhanced 3D thermal field model achieves a 363% increase in the number of detected high-temperature regions, with the coverage area expanding nearly 6-fold. Notable improvements are observed in fire boundary delineation and thermal gradient representation.

These results validate the engineering applicability of the NRBO-XGBoost model under complex field conditions, providing reliable technical support for coal mine fire monitoring and disaster prevention. However, several limitations and challenges remain to be addressed in practical deployment. The current temperature correction process employs a post-processing approach, limiting real-time monitoring and rapid emergency response capabilities. Furthermore, the substantial computational resources required to generate high-resolution 3D thermal models hinder efficient analysis of large-scale coal seam fire areas. To overcome these constraints, future research will focus on two key areas: developing real-time correction models based on edge computing and integrating multimodal sensor data to enhance the accuracy and interpretability of thermal anomaly identification. These advancements are expected to improve the precision of fire spread modeling, thereby supporting the development of more effective large-scale coal seam fire prevention and control strategies.