Transformational Leadership and Safety Attitudes in Firefighting: Evidence on the Moderating Role of Perceived Accident Likelihood from South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

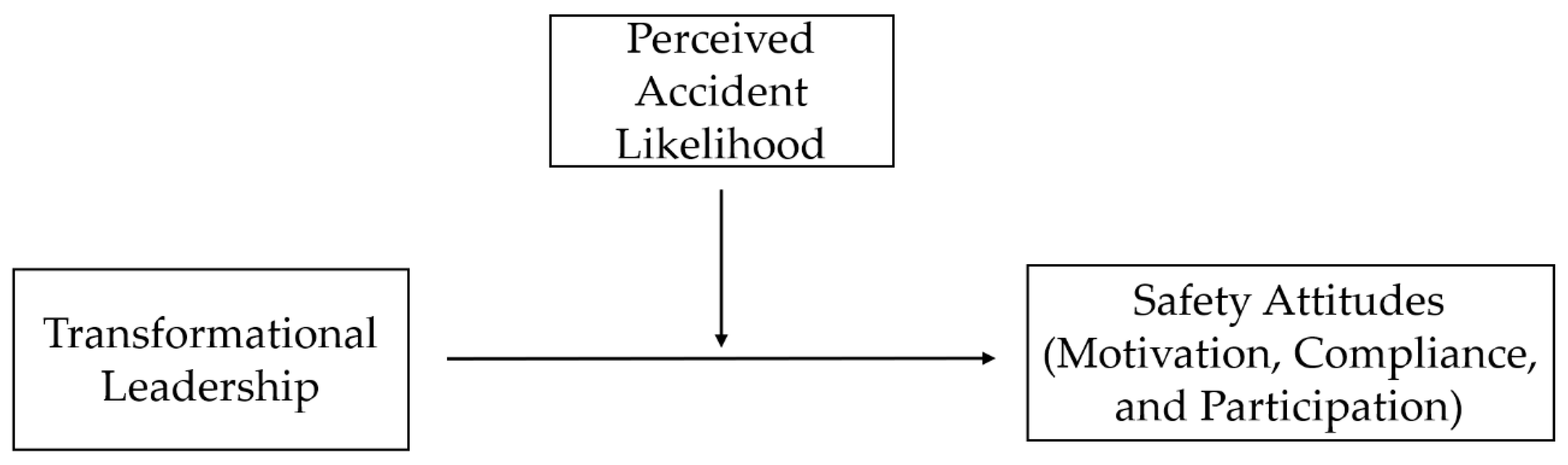

2. Theoretical Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Transformational Leadership and Safety Attitudes

2.2. Accident Likelihood and Safety Attitudes as Well as the Moderating Role of Perceived Accident Likelihood

3. Data and Measures

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Controls and Measurement Validity

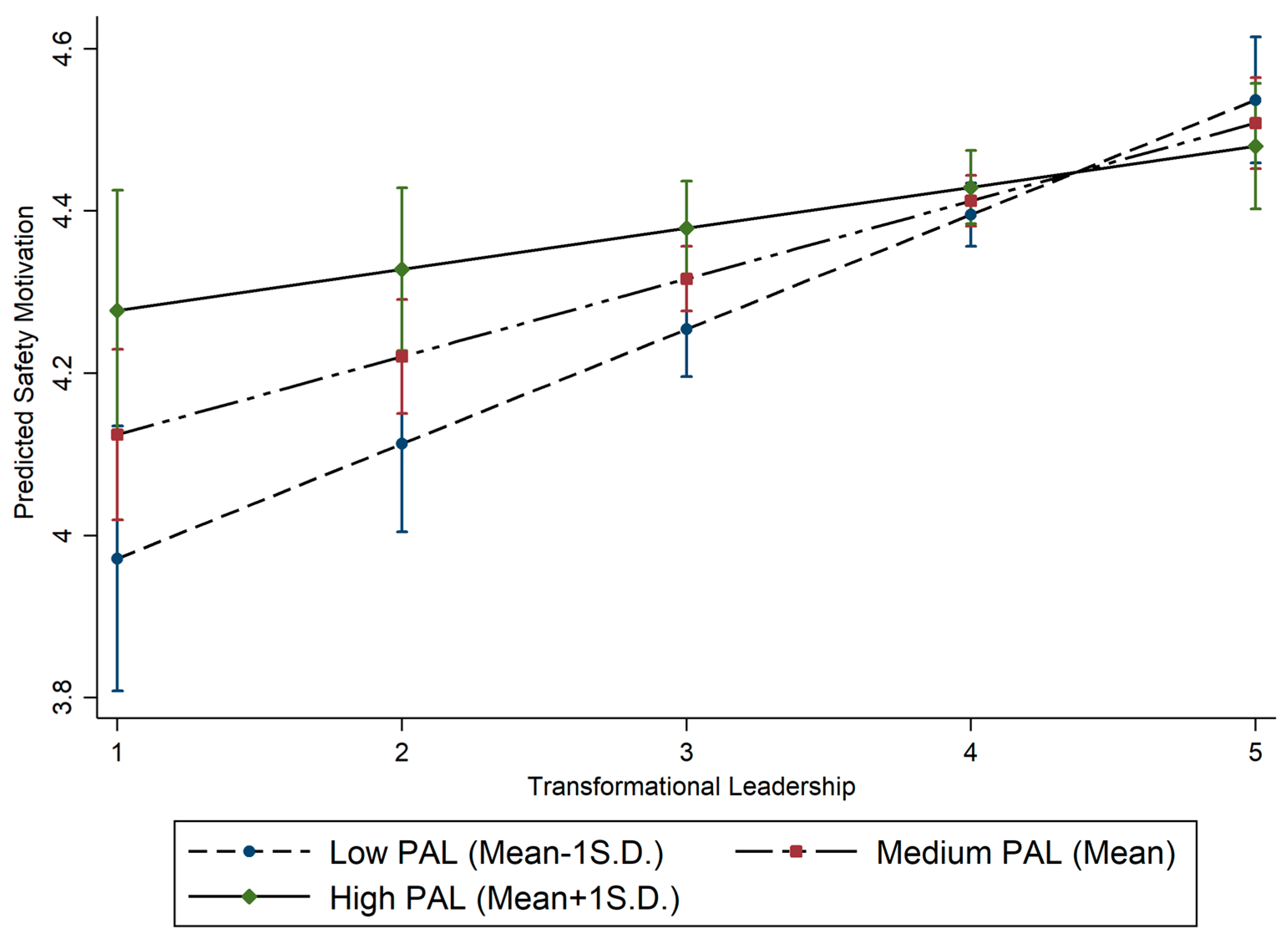

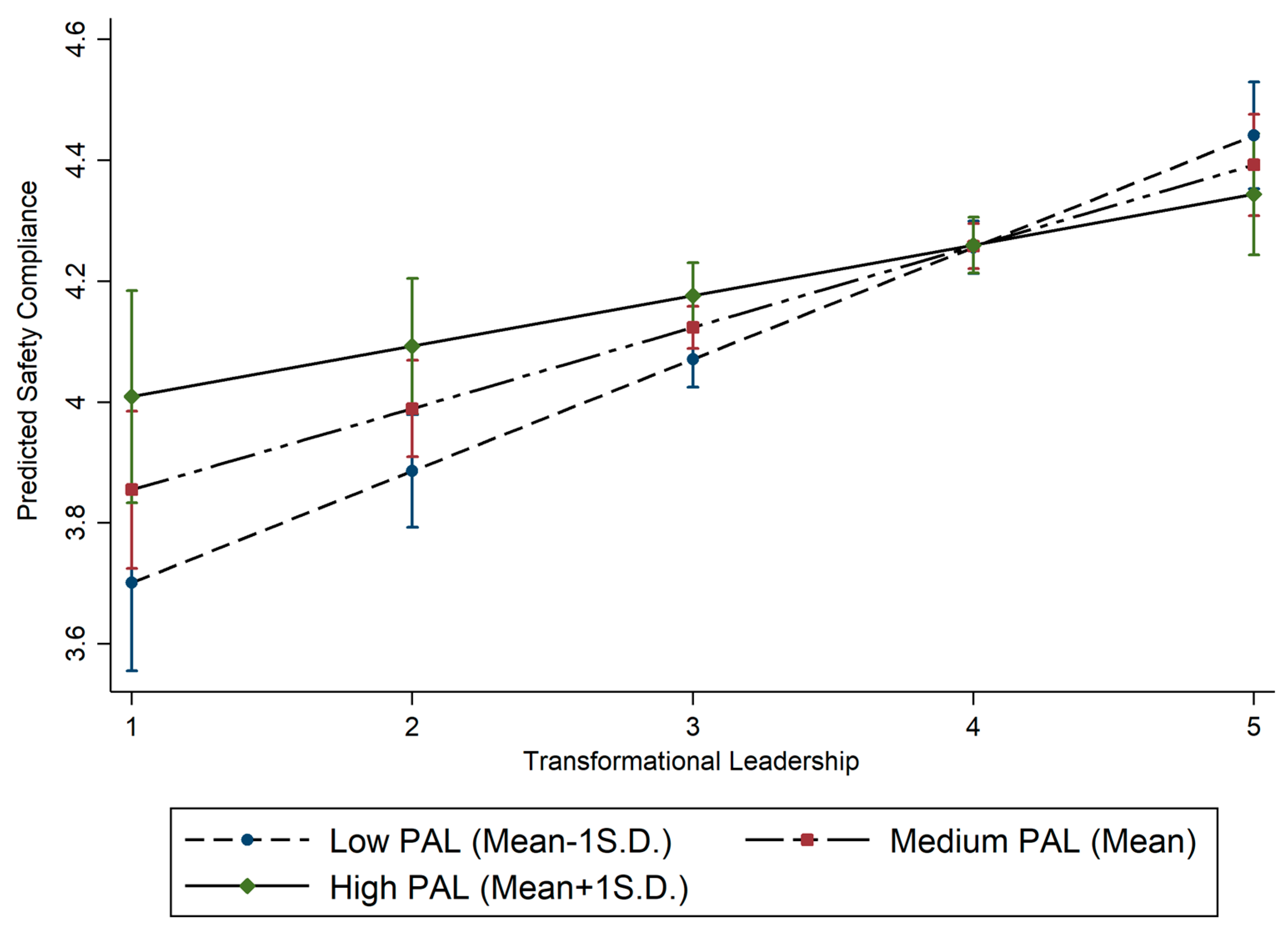

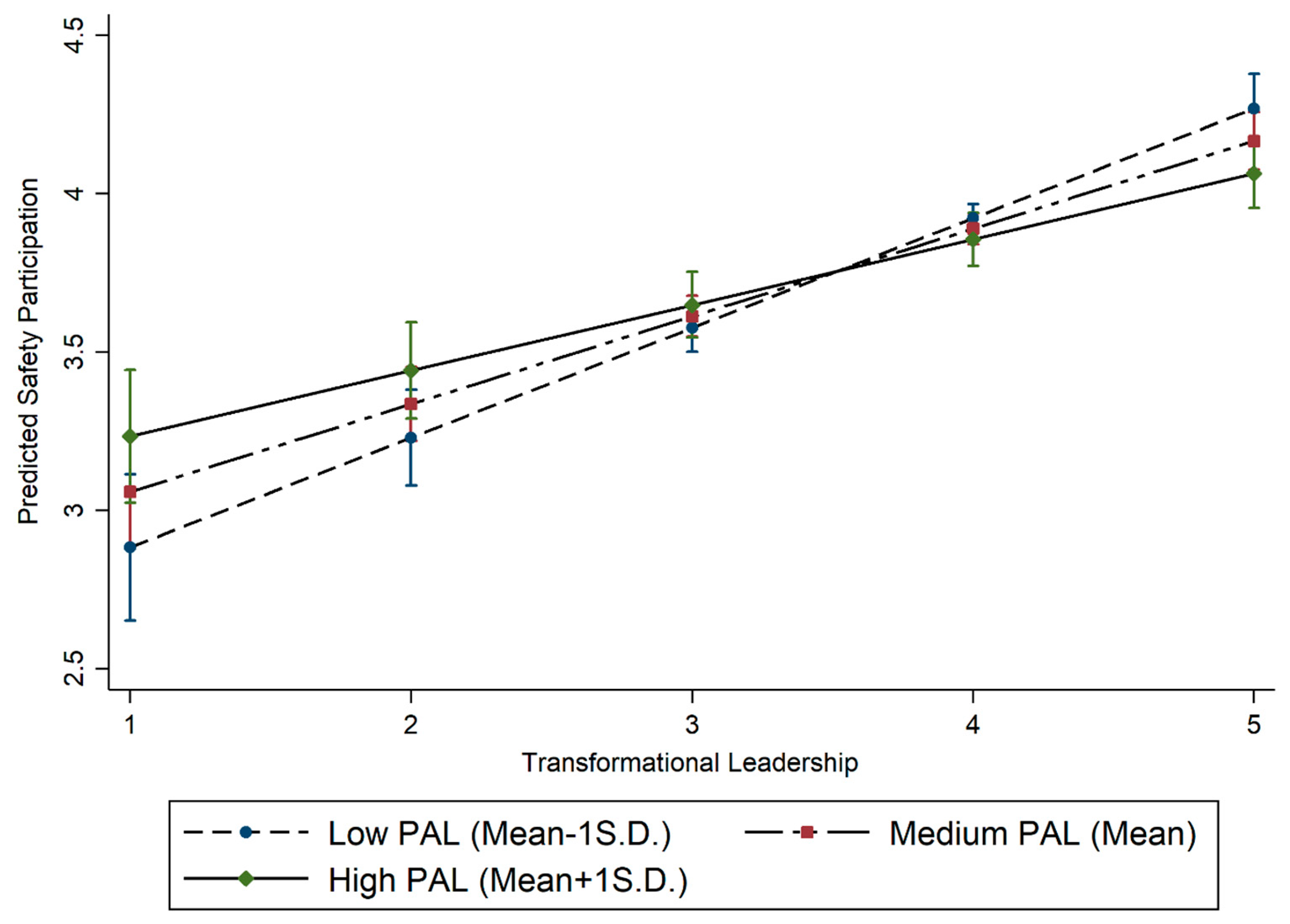

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Butry, D.T.; Webb, D.H.; Gilbert, S.W.; Taylor, J. The Economics of Firefighter Injuries in the United States; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/publications/economics-firefighter-injuries-united-states (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Willis, S.; Clarke, S.; O’Connor, E. Contextualizing Leadership: Transformational Leadership and Management-By-Exception-Active in Safety-Critical Contexts. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 90, 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S. Safety Leadership: A Meta-Analytic Review of Transformational and Transactional Leadership Styles as Antecedents of Safety Behaviours. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 86, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, J.E.; Kelloway, E.K. Safety Leadership: A Longitudinal Study of the Effects of Transformational Leadership on Safety Outcomes. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barling, J.; Loughlin, C.; Kelloway, E.K. Development and Test of a Model Linking Safety-Specific Transformational Leadership and Occupational Safety. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D.; Eldridge, F.; DeJoy, D.M. Safety-Specific Transformational and Passive Leadership Influences on Firefighter Safety Climate Perceptions and Safety Behavior outcomes. Saf. Sci. 2016, 86, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arezes, P.M.; Miguel, A.S. Risk Perception and Safety Behaviour: A Study in an Occupational Environment. Saf. Sci. 2008, 46, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priolo, G.; Vignoli, M.; Nielsen, K. Risk Perception and Safety Behaviors in High-Risk Workers: A Systematic Literature review. Saf. Sci. 2025, 186, 106811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearns, K.; Flin, R. Risk Perception and Attitudes to Safety by Personnel in the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry: A Review. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 1995, 8, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A. Safety Climate and Safety Performance. In The Psychology of Workplace Safety; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A. A Study of the Lagged Relationships among Safety Climate, Safety Motivation, Safety Behavior, and Accidents at the Individual and Group Levels. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Improving Organizational Effectiveness Through Transformational Leadership; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. MLQ Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire for Research: Permission Set; Mind Garden: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Riggio, R.E. Transformational Leadership; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R.W. A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. Cognitive and Physiological Processes in Fear Appeals and Attitude change: A Revised Theory of Protection Motivation. In Social Psychophysiology: A Sourcebook; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd, D.L.; Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W. A Meta-Analysis of Research on Protection Motivation Theory. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, F.E. A Theory of Ledership Effectiveness; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hersey, P.; Blanchard, K.H. Management of Organizational Behavior: Utilizing Human Resources; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty, A.E.; Griffin, M.A. Dimensions of Transformational Leadership: Conceptual and Empirical Extensions. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Piccolo, R.F. Transformational and Transactional Leadership: A Meta-Analytic Test of Their Relative Validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, Y.; Ruan, R.; Zheng, J. Divergent Effects of Transformational Leadership on Safety Compliance: A Dual-Path Moderated Mediation Model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, F.; Mahdinia, M.; Doosti-Irani, A. Safety-Specific Transformational Leadership and Safety Outcomes at Workplaces: A Scoping Review Study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, I.; Vlerick, P. Transformational Leadership and Safety Performance among Nurses: The Mediating Role of Knowledge-Related Job Characteristics. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Mullen, J.; Francis, L. Divergent Effects of Transformational and Passive Leadership on Employee Safety. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ree, E.; Wiig, S. Linking Transformational Leadership, Patient Safety Culture and Work Engagement in Home Care Services. Nurs. Open 2019, 7, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, S.S.; Alabdulkarim, S.; Chan, A.H.S.; Zhang, T. The Acceptance of Personal Protective Equipment among Hong Kong Construction Workers: An Integration of Technology Acceptance Model and Theory of Planned Behavior with Risk perception and Safety Climate. J. Saf. Res. 2021, 79, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D.; Luria, G. A Multilevel Model of Safety Climate: Cross-Level Relationships between Organization and Group-Level Climates. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, A.B.; Mullins-Jaime, C.; Smith, T.D. The Impact of Safety Leadership on Safety Behaviors of Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting Personnel during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2024, 31, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyeonggi Provincial Council. A Study on Policy Measures to Improve the Happiness Index of Firefighters in Gyeonggi Province. 2020. Available online: https://memory.library.kr/items/show/210053287 (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Pandey, S.K.; Davis, R.S.; Pandey, S.; Peng, S. Transformational Leadership and the Use of Normative Public Values: Can Employees Be Inspired to Serve Larger Public Purposes? Public Admin 2016, 94, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Bradley, J.C.; Wallace, J.C.; Burke, M.J. Workplace safety: A Meta-Analysis of the Roles of Person and Situation Factors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1103–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Locke, E.A.; Durham, C.C.; Kluger, A.N. Dispositional Causes of Job Satisfaction: A Core Evaluations Approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, R.; Peng, S.; Pandey, S.K. Testing the Effect of Person-Environment Fit on Employee Perceptions of Organizational Goal Ambiguity. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2014, 37, 465–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kapp, E.A. The Influence of Supervisor Leadership Practices and Perceived Group Safety Climate on Employee Safety Performance. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Managing the Unexpected: Assuring High Performance in an Age of Complexity; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Flin, R.; Mearns, K.; O’Connor, P.; Bryden, R. Measuring Safety Climate: Identifying the Common Features. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D.A.; Burke, M.J.; Zohar, D. 100 Years of Occupational Safety Research: From Basic Protections and Work Analysis to A Multilevel Model of Safety Culture/Climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. A Social Information Processing Approach to Job Attitudes and Task Design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective Events Theory: A Theoretical Discussion of the Structure, Causes and Consequences of Affective Experiences at Work. Res. Organ. Behav. 1996, 18, 34–74. [Google Scholar]

- Staw, B.M.; Sandelands, L.E.; Dutton, J.E. Threat-Rigidity Effects in Organizational Behavior. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 26, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R.G.; Maher, K.J. Leadership and Information Processing: Linking Perceptions and Performance; Unwin Hyman: Boston, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Mean | S.D. | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety motivation | 4.38 | 0.58 | 2 | 5 |

| Safety compliance | 4.21 | 0.63 | 1.67 | 5 |

| Safety participation | 3.79 | 0.73 | 1 | 5 |

| Transformational leadership (TFL) | 3.61 | 0.70 | 1 | 5 |

| Perceived accident likelihood | 3.05 | 0.92 | 1 | 5 |

| Job satisfaction | 3.95 | 0.66 | 1 | 5 |

| Affective commitment | 4.03 | 0.73 | 1 | 5 |

| Safety culture | 4.37 | 0.64 | 1.33 | 5 |

| Gender | 0.14 | 0.34 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | 2.34 | 0.96 | 1 | 4 |

| Education | 2.32 | 0.83 | 1 | 4 |

| Tenure | 1.61 | 0.84 | 1 | 4 |

| Job grade | 1.80 | 0.88 | 1 | 4 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| (2) | 0.590 *** | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (3) | 0.518 *** | 0.598 *** | 1.000 *** | ||||||||||

| (4) | 0.373 *** | 0.402 *** | 0.481 *** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (5) | −0.006 | −0.042 | −0.103 *** | −0.164 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (6) | 0.378 *** | 0.445 *** | 0.461 *** | 0.430 *** | −0.081 *** | 1.000 | |||||||

| (7) | 0.382 *** | 0.438 *** | 0.470 *** | 0.438 *** | −0.145 *** | 0.683 *** | 1.000 | ||||||

| (8) | 0.521 *** | 0.447 *** | 0.385 *** | 0.420 *** | −0.027 | 0.348 *** | 0.372 *** | 1.000 | |||||

| (9) | −0.089 *** | −0.137 *** | −0.149 *** | −0.083 *** | 0.008 | −0.135 *** | −0.142 *** | −0.065 ** | 1.000 | ||||

| (10) | 0.092 *** | 0.096 *** | 0.223 *** | 0.055 ** | −0.004 | 0.126 *** | 0.119 *** | 0.112 *** | −0.152 *** | 1.000 | |||

| (11) | −0.030 | −0.105 *** | −0.067 *** | −0.059 ** | −0.017 | −0.075 *** | −0.085 *** | −0.054** | 0.130 *** | −0.047 | 1.000 | ||

| (12) | 0.110 *** | 0.103 *** | 0.219 *** | 0.109 *** | −0.016 | 0.124 *** | 0.126 *** | 0.143 *** | −0.109 *** | 0.812 *** | −0.128 *** | 1.000 | |

| (13) | 0.105 *** | 0.101 *** | 0.208 *** | 0.081 *** | −0.020 | 0.127 *** | 0.133 *** | 0.136 *** | −0.092 *** | 0.798 *** | −0.078 *** | 0.842 *** | 1.000 |

| Variables | Safety Motivation | Safety Compliance | Safety Participation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Main Effects | Model 2: Interaction Effects | Model 1: Main Effects | Model 2: Interaction Effects | Model 1: Main Effects | Model 2: Interaction Effects | |||||||

| Coef. | (S.E.) | Coef. | (S.E.) | Coef. | (S.E.) | Coef. | (S.E.) | Coef. | (S.E.) | Coef. | (S.E.) | |

| Transformational leadership (TFL) | 0.098 | 0.019 *** | 0.247 | 0.068 *** | 0.136 | 0.025 *** | 0.303 | 0.054 *** | 0.280 | 0.030 *** | 0.508 | 0.080 *** |

| Perceived accident likelihood | 0.032 | 0.015 ** | 0.216 | 0.082 *** | 0.017 | 0.013 | 0.223 | 0.068 *** | −0.015 | 0.026 | 0.266 | 0.093 *** |

| TFL × Perceived accident likelihood | −0.049 | 0.021 *** | −0.055 | 0.017 *** | −0.076 | 0.022 *** | ||||||

| Job satisfaction | 0.105 | 0.031 *** | 0.104 | 0.030 *** | 0.174 | 0.035 *** | 0.173 | 0.034 *** | 0.175 | 0.050 *** | 0.174 | 0.049 *** |

| Affective commitment | 0.088 | 0.024 *** | 0.089 | 0.023 *** | 0.118 | 0.030 *** | 0.119 | 0.030 *** | 0.163 | 0.038 *** | 0.165 | 0.037 *** |

| Safety culture | 0.354 | 0.024 *** | 0.351 | 0.023 *** | 0.258 | 0.031 *** | 0.254 | 0.032 *** | 0.154 | 0.030 *** | 0.150 | 0.030 *** |

| Gender | −0.040 | 0.035 | −0.043 | 0.035 | −0.098 | 0.048 ** | −0.100 | 0.048 ** | −0.106 | 0.046 ** | −0.110 | 0.046 ** |

| Age | −0.001 | 0.023 | −0.002 | 0.023 | 0.020 | 0.023 | 0.019 | 0.022 | 0.098 | 0.029 *** | 0.096 | 0.029 *** |

| Education | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | −0.038 | 0.013 ** | −0.036 | 0.013 *** | −0.001 | 0.019 | 0.001 | 0.019 |

| Tenure | 0.008 | 0.022 | 0.005 | 0.023 | −0.027 | 0.032 | −0.030 | 0.031 | 0.015 | 0.033 | 0.010 | 0.032 |

| Job grade | 0.003 | 0.024 | 0.006 | 0.025 | 0.008 | 0.028 | 0.011 | 0.028 | 0.005 | 0.031 | 0.010 | 0.031 |

| Constant | 1.568 | 0.128 *** | 1.020 | 0.289 *** | 1.463 | 0.136 *** | 0.849 | 0.228 *** | 0.558 | 0.170 *** | −0.281 | 0.304 |

| R-squared | 0.336 | 0.339 | 0.333 | 0.337 | 0.376 | 0.381 | ||||||

| n | 1502 | 1504 | 1503 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moon, K.-K.; Lim, J. Transformational Leadership and Safety Attitudes in Firefighting: Evidence on the Moderating Role of Perceived Accident Likelihood from South Korea. Fire 2025, 8, 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8110435

Moon K-K, Lim J. Transformational Leadership and Safety Attitudes in Firefighting: Evidence on the Moderating Role of Perceived Accident Likelihood from South Korea. Fire. 2025; 8(11):435. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8110435

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoon, Kuk-Kyoung, and Jaeyoung Lim. 2025. "Transformational Leadership and Safety Attitudes in Firefighting: Evidence on the Moderating Role of Perceived Accident Likelihood from South Korea" Fire 8, no. 11: 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8110435

APA StyleMoon, K.-K., & Lim, J. (2025). Transformational Leadership and Safety Attitudes in Firefighting: Evidence on the Moderating Role of Perceived Accident Likelihood from South Korea. Fire, 8(11), 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8110435