1. Introduction

Firefighting is internationally acknowledged as an inherently high-risk occupation, exposing firefighters to a wide range of harmful factors, including physical, chemical, biological and psychosocial risks [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. When disasters occur in the international community, they are dispatched overseas as international structural members to carry out fire suppression and structural activities, and are unique in various firefighting activities such as flood damage, forest fires, general fires, explosions, collapses, traffic accidents, life safety accidents, and providing emergency medical services when emergency patients arise [

6,

7,

8]. In addition, while performing civilian-facing duties such as fire prevention, public safety education, training, inspection of fire equipment and fire vehicles, fire investigation, and fire prevention, they are exposed to many occupational risk factors, including injuries and musculoskeletal strain [

9,

10,

11]. In 2023, there were 240,861 fire incidents, 511,562 rescue incidents, 469,905 public safety incidents, and 1,804,893 emergency incidents. In order to carry out specialized firefighting duties at such a large number of call sites, firefighters undergo specialized education and training, and in 2024, 29,143 people received education and training at fire academies nationwide [

12].

In terms of occupational environment, industrial workers work in designated locations, so occupational exposure risks are predictable, whereas firefighters have three types of occupational exposures: fire station space, emergency response routes to accident sites, and accident sites to which they have responded. Since occupational risk factors are variable and unpredictable, the risk of developing work-related injuries and diseases is very high, making on-site safety and health management relatively difficult [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

There is growing global concern about the health burden of firefighters, and epidemiological studies in Western countries have reported higher prevalence of cardiovascular, metabolic and respiratory diseases, and occupational hearing loss compared to the general population [

21,

22,

23,

24]. However, systematic studies in Asian populations are still limited. In particular, most previous studies in Korea have focused on mental health issues such as post-traumatic stress syndrome, depression, and burnout, and have focused on acute health effects and case studies [

3,

25,

26,

27]. Few studies have provided population-based prevalence estimates or comparative indicators based on representative study subjects, and few have compared the disease burden among Korean firefighters with that of the general population. Despite warnings about the health risks associated with occupational exposures during firefighting activities, no epidemiological study has directly compared chronic diseases and occupational diseases among firefighters in Korea using the population-based occupational health examination data with the general population. Existing studies have been limited by their limited sample size and lack of standardized indicators, primarily focusing on mental health or single-center case reports. Therefore, this study will serve as a starting point for quantitatively assessing the true burden of disease among firefighters in a large city and the differences between these two groups and the general population. In this respect, calculation of standardized prevalence ratios is a useful mechanistic approach to quantify the disease burden of occupational cohorts compared with expectations for the general population after controlling for age and sex [

28]. In particular, calculating standardized prevalence costs will enable policymakers to identify occupational health disparities and provide the evidence necessary to establish disease prevention strategies by separating and analyzing the disease and pre-disease stages of firefighters, who are presumed to be healthy workers [

29,

30].

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to calculate SPRs and compare the prevalence of occupational diseases such as pulmonary ventilation disorders (PVD) and noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) and chronic diseases such as obesity, hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), and metabolic syndrome (MetS) among Korean firefighters with that of the general population. Ultimately, understanding the factors that increase health risks for firefighters and providing a basis for developing occupational safety and health policies will enable us to provide customized interventions for high-risk groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

Korean firefighters are legally required to undergo annual occupational health examinations under the Firefighters Health, Safety, and Welfare Act. These results are submitted by the screening hospital to their respective fire departments. However, there is no systematic approach to analyzing these results at the fire department level. Mental health is assessed through questionnaires, and physical health is assessed through physical examination results. In Korea, health management currently focuses primarily on mental health issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and sleep disorders. In particular, research on the health of Korean firefighters has focused on identifying risk and protective factors for brain and mental health, identifying recovery factors from PTSD aftereffects, risk factors associated with heart health, and follow-up studies on occupational and rare cancers. However, research on physical health using screening results is severely lacking.

2.2. Study Design and Population

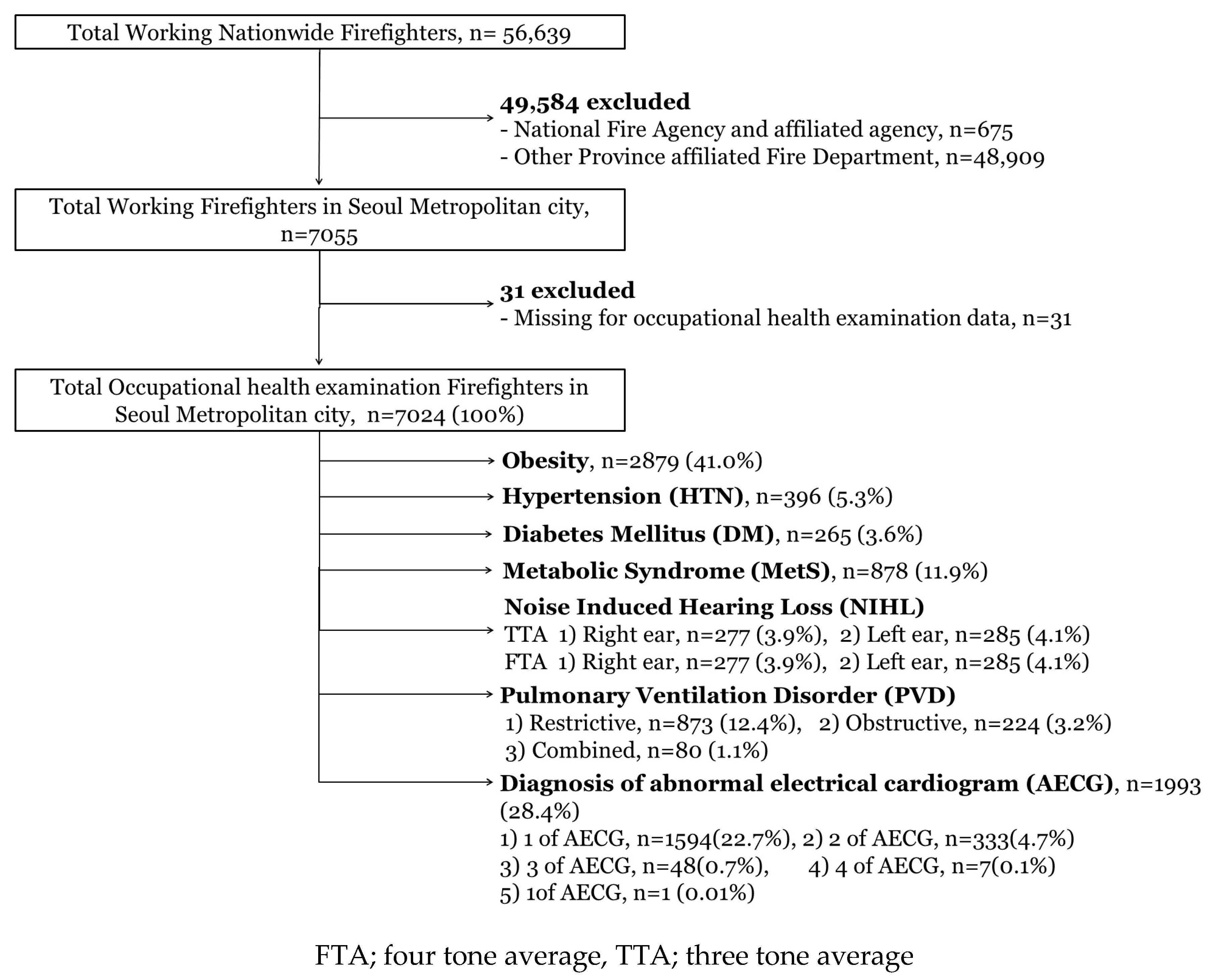

The research was conducted using a community-based retrospective cross-sectional study. The participants in this study were divided into two groups: firefighters and the general population. First, of the 56,639 firefighters nationwide, 7055 are Seoul metropolitan firefighters working in the metropolitan area. Of the total participants, 7024 individuals were included in this study following the exclusion of 31 subjects who lacked occupational health examination results for the given year. To compare SPRs with the general population, researchers used general population data from the 2019 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Of the 8110 study participants in 2019, 1485 general population participants were included in the study analysis. The general population study subjects were those with working conditions similar to those of firefighters. Specifically, participants were excluded from this study if they were under 20 years of age, over 60 years of age, not full-time employees (those working less than 37.5 h per week), had missing values for shift patterns, occupational information, or measures of diseases used in this study.

2.3. Data Source and Collection

This study analyzed data from two distinct sources. The primary dataset consisted of occupational health examination results from 7024 firefighters affiliated with the Seoul Metropolitan Fire and Disaster Prevention Headquarters. These examinations were conducted at twelve designated screening facilities in Seoul in 2019. All firefighter occupational health examinations analyzed in this study were conducted according to legally mandated national standards, including standardized test items, measurement methods, personnel qualifications, data entry units, and reporting protocols. Additionally, the data utilized in this research were publicly available, being systematically collected and maintained by the Seoul Metropolitan Fire and Disaster Prevention Headquarters. Personal health checkup data for firefighters were compiled by individual medical institutions’ health examination centers, after which the aggregated firefighter health database was curated by the Seoul Metropolitan Fire and Disaster Management Headquarters. To enhance data integrity, minimum and maximum value ranges for each variable were predefined to mitigate errors during data entry. Overall, this study leveraged publicly accessible data pertaining to the occupational health examination outcomes of firefighters in metropolitan regions.

The second data source comprises publicly available information provided by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, specifically the results from the 2019 National Health and Nutrition Survey. The survey population is determined annually through the Population and Housing Survey, which selects 192 survey districts stratified by capital city, town, village, and housing type. Subsequently, household members are randomly chosen from an approximate sample of 10,000 individuals. This stratified multistage probability sampling design ensures the generation of representative national data. The survey will be divided into two categories: health checkups, health surveys, and nutrition surveys.

2.4. Variables

This study utilized the 2019 occupational health examination data for all firefighters employed by the Fire Headquarters within the Seoul metropolitan area. The data incorporated various variables related to firefighters’ health status and occupational factors. The occupational health examination data for firefighters, general population utilized in this study encompassed the following variables: (1) sociodemographic information including sex, age, job rank, current position, total length of service as a firefighter, and shift work status; and (2) clinical physical examination parameters such as height, weight, waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, pure-tone audiometry results, fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1, %), forced vital capacity (FVC, %), and the ratio of FEV1 to FVC (FEV1/FVC, %). (3) Occupational health examination results are classified into five categories: A, C1, C2, D1, and D2. A indicates a healthy individual who does not require follow-up care. C1 indicates an individual with an occupational disease requiring observation, such as follow-up, due to a risk of developing an occupational disease. C2 indicates an individual with a general disease requiring observation, such as follow-up, due to a risk of developing a general disease. D1 indicates an individual with a possible occupational disease requiring follow-up care due to the presence of an occupational disease. D2 indicates an individual with a possible general disease requiring follow-up care.

Firefighters’ diseases and pre-disease stages are diagnosed at a screening hospital with standardized health screening items and measurement units, and the examination results are provided to individual firefighters and fire departments. This study compared the standardized prevalence ratios of chronic diseases and occupational diseases between firefighters and the general population using public data provided to fire departments, and thus applied the same diagnostic criteria to both population groups. The disease stages and pre-disease stages of the disease group corresponding to chronic diseases are as follows: In the case of obesity, the pre-disease stage is when the body mass index (BMI) is 23 to 24.9, and the disease stage is when it is 25 or higher. In the case of hypertension, the pre-disease stage is when systolic blood pressure is 130 to 139 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure is 80 to 89 mmHg, and the disease stage is when systolic blood pressure is 140 mmHg or higher or diastolic blood pressure is 90 mmHg or higher. In the case of systolic hypertension alone, a systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg was also included as a disease stage. In the case of diabetes, the pre-disease stage is when the fasting blood sugar level is 100–125 mg/dL, and the disease stage is when it is 126 mg/dL or higher. For metabolic syndrome, the pre-disease stage refers to cases where one or two of the five detailed criteria are met, and the disease stage refers to cases where three or more of the five criteria are diagnosed. The five detailed criteria are as follows: (1) Waist circumference (men 90 cm or more, women 85 cm or more), (2) Blood pressure (130/85 mmHg or more), (3) Triglyceride 150 m, (4) HDL cholesterol (men 40 mg/dL or less, women 50 mg/dL or less), (5) Fasting blood sugar 100 mg/dL or more. Occupational diseases included pulmonary ventilation disorders and noise-induced hearing loss. Pulmonary ventilation disorders was classified as restrictive (FEV1/FVC ≥ 70% and FVC < 80%), obstructive (FEV1/FVC < 70% and FVC ≥ 80%), and mixed (FEV1/FVC < 70% and FEV1 < 80% and FVC < 80%), and noise-induced hearing loss was divided into three and four categories, and the prevalence rates for the right and left sides were presented, respectively.

2.5. Outcome Measure

The primary outcome of this study was the standardized prevalence ratio (SPR), an indirect standardization method that adjusts for differences in age and sex distribution between study groups. SPR was calculated as the ratio of observed cases of each disease among firefighters to the expected number of cases in a population with the same age and sex structure, based on general population prevalence rates (

Figure 1). An SPR above 1 indicates a higher prevalence in firefighters; an SPR below 1 indicates lower prevalence compared to the general population. Separate SPRs were calculated for chronic diseases (obesity, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome), which were further divided into pre-disease and disease stages, as well as for occupational diseases (pulmonary ventilation disorders and noise-induced hearing loss, assessed using the four-tone average (FTA) and three-tone average (TTA) methods).

The secondary endpoint of this study involved conducting an epidemiological analysis of firefighter occupational health examination results using comprehensive census data. Disease classifications based on ICD-10 codes were compiled and included conditions such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, pulmonary ventilation impairment measured by vital capacity, noise-induced hearing loss, and electrocardiogram abnormalities The demographics of firefighters were analyzed based on shift work status and job-specific characteristics.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

In the results presented for demographic characteristics, categorical variables were reported as percentages, and continuous variables corresponding to age, total working experienced year were expressed as values including mean, median, and interquartile range (IQR). All prevalence ratios adjusted for age and sex including chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome, as well as occupational diseases like pulmonary ventilation disorders and noise-induced hearing loss were calculated by applying indirect standardization methods using the 2010 census data as the standard population.

All age- and sex-adjusted prevalence ratios for chronic conditions including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome as well as occupational diseases such as pulmonary ventilation disorders and noise-induced hearing loss, were calculated using the 2010 census data as the standard population through indirect standardization methods. In addition, chi-square tests were performed to evaluate demographic characteristics by shift work type and job title of firefighters. Statistical diagnostics were performed to confirm underlying model assumptions, including population structure. Sensitivity analyses entailed recalculating SPRs under alternative analytic choices (standard population, inclusion criteria, sub-group analyses) to assess robustness. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

4. Discussion

This study compared the disease prevalence rates of the general population by calculating SPRs using firefighter occupational health examination data, dividing them into pre-disease and disease stages.

4.1. Implications for the SPRs of Chronic and Occupational Diseases in Firefighters

This study examined the SPRs of both chronic diseases and occupational health conditions among Korean firefighters in comparison to the general population. Notably, the prevalence of chronic diseases in the disease stage such as obesity, HTN, DM, and Mets among firefighters was similar to or lower than that in the general population, with SPRs either close to 1 or significantly below 1. Additionally, obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity were significantly lower than expected, and metabolic syndrome did not show a statistically significant increase in the risk.

Similarly, the SPRs for work-related diseases including restrictive, obstructive, and combined ventilatory disorders and noise-induced hearing loss were lower or similar in firefighters than in the general population. These findings are consistent with the concept of the “healthy worker effect”. Firefighters, who not only undergo rigorous health screening and employment physical requirements, but also routinely participate in systematic physical conditioning programs, maintain high levels of physical fitness, and may receive dedicated nutritional guidance, are likely to be healthier in terms of disease burden. This multifaceted approach—including occupational fitness standards, regular onsite training, and a health-conscious work culture—contributes to the “healthy worker effect” observed in this population.

In contrast, when evaluating pre-disease (risk group) stages, the SPRs for obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome were notably higher in firefighters than in the general population. This suggests that although active recruitment and selection mechanisms may suppress clinical disease manifestations, underlying risk factors for chronic diseases are more common among firefighters due to exposure to workplace hazards. Such tendencies may reflect the unique occupational exposures and stressors encountered in firefighting, including irregular work schedules, exposure to hazardous substances, intermittent intense physical demands, and psychological stress.

These findings underscore the importance of regular health surveillance and early intervention strategies in firefighter cohorts. Occupational health programs should focus not only on monitoring clinical disease but also on identifying and managing risk factors at the preclinical stage to prevent future disease progression. Additionally, the higher burden of metabolic syndrome and hypertension risk among firefighters highlights the need for targeted preventive efforts, such as lifestyle modification programs, environmental controls, and stress management interventions.

4.2. Comparison of Research Results on Chronic Diseases and Occupational Diseases Among Domestic and Foreign Firefighters

This study found that Korean firefighters exhibited SPRs near or below 1 for clinical-stage chronic diseases such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus compared with the general population. This contrasts with several international studies reporting elevated or near-unity SPRs for these conditions among firefighters. Moffatt et al. reported obesity prevalence in US firefighters with SPRs ranging from 1.1 to 1.3 compared to the general population, and Beckett et al. found hypertension SPRs of approximately 1.1 to 1.4 in Western firefighter cohorts [

31,

32]. The markedly lower SPR for hypertension and diabetes mellitus in our Korean cohort likely reflects a combination of factors, including a strong healthy worker effect, rigorous occupational health screening, early exclusion of individuals with overt chronic disease, and importantly, differences in nutritional habits and lifestyle patterns between countries. The generally healthier dietary profile in South Korea compared to the United States may partly explain the lower prevalence of these metabolic conditions observed in Korean firefighters, consistent with prior reports on international health disparities [

33,

34]

In terms of metabolic syndrome, these results showed an SPR of 1.01 in the clinical disease stage and significantly elevated SPRs in pre-disease risk groups (SPR = 1.62), similar to international findings where firefighters exhibit higher metabolic risk factors even when overt disease prevalence is controlled. This highlights a latent burden of cardio-metabolic risk among Korean firefighters. While global evidence suggests that occupational stressors and irregular work patterns may contribute to early metabolic dysfunction, metabolic syndrome is a multifactorial condition influenced by a complex interplay of genetic factors, physical fitness, nutritional habits, lifestyle, and various occupational exposures. Therefore, the contribution of occupational stress in this physically well-trained group should be interpreted with due caution [

35].

Concerning occupational health conditions, SPRs for PVDs and NIHL in our study were generally lower than or comparable to the general population, contrasting somewhat with overseas data. US-based studies reported higher SPRs for obstructive airway disease and NIHL, suggesting greater occupational exposure effects [

36,

37,

38]. The lower SPRs observed in Korean firefighters may reflect comprehensive health surveillance programs and stringent fitness requirements, but may also indicate underdiagnosis or differences in exposure intensities.

Overall, these results underscore the presence of a healthy worker effect in Korean firefighters, consistent with similar patterns in occupational health literature. While overt chronic and work-related diseases appear well managed in this population, the elevated pre-disease metabolic risks call for reinforced preventive strategies focusing on early intervention.

4.3. Implications of Analysis Using Representative Data from Occupational Health Examinations Among Metropolitan Firefighters in Korean

International research on firefighter health is more advanced and varied, with several U.S. states documenting associations between prolonged occupational exposures and increased risks of diseases including cancer. Longitudinal cohort studies examining related health outcomes are actively ongoing. However, Korea has yet to establish a nationwide database integrating results from specialized health examinations for in-depth analysis, and a systematic job exposure matrix (JEM) based on individual firefighters’ occupational histories remains undeveloped. This gap challenges firefighters’ ability to substantiate claims of occupational disease causation, such as in cases of cancer.

To maximize epidemiological insights, integration of firefighters’ occupational exposure data—encompassing site deployments, transit routes, and station environments—alongside the occupational health examination results is imperative. Construction of a job exposure matrix stratified by duties (fire suppression, rescue, emergency medical services, administration, dispatch) and service duration is necessary for comprehensive risk assessment. Variations in exposure history, such as pre- and post-introduction of self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) or implementation of smoke reduction infrastructure, likely influence health outcomes and provide critical data for future occupational health policy and prevention strategies.

This study analyzed the health status of firefighters in a large city through a comprehensive survey at a time when a systematic data collection system was not yet in place. For firefighters in the disease and pre-disease stages, a proactive management approach, including disease treatment and health promotion programs at the fire department level, is necessary. In particular, research should be conducted to identify the link between occupational risk factors and health outcomes through organic linkage with individual dispatch data, occupational environmental measurements, and data on work-related injuries occurring at firefighting scenes.

4.4. Strength, Limitations and Further Study

The most compelling strength of this study is that it uses data from occupational health examinations of all firefighters working in metropolitan area of Seoul to divide chronic and occupational diseases into pre- and disease stages, calculating standardized prevalence ratios for the general population. No previous population-based study has analyzed the results of occupational health checkups using complete data. Therefore, these results are representative of the broader context. However, this study has several limitations: potential residual confounding due to the failure to control for demographic or lifestyle factors, the limited detection of overt disease due to the healthy worker effect, and the cross-sectional nature of the study, which may have exacerbated the strong presence of the healthy worker effect. Another limitation is that the data used in this study lacked information on the level and pattern of physical activity among firefighters. While physical activity can significantly impact health outcomes, it is excluded from the fire department’s proactive data collection system. Furthermore, the possibility of underdiagnosis of pulmonary ventilation disorders and noise-induced hearing loss in Korean firefighters has not yet been clearly elucidated, as this paper suggests, due to the limitations of the cross-sectional study design. Therefore, further research using long-term accumulated data will be necessary. Nevertheless, this study provides a comprehensive epidemiological comparison of the physical health of Korean firefighters and can contribute to the development of occupational health policies for essential personnel. Future research should be conducted using a multifaceted approach by establishing a cohort of Korean firefighters.

5. Conclusions

This study was a community-based retrospective cross-sectional study. Using data from the 2019 Firefighter occupational health examination and the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, we calculated SPRs, an indirect standardization method, for chronic diseases and occupational diseases among firefighters compared with those of the general population. As a result, Korean firefighters showed a relatively lower risk of chronic diseases and occupational disease compared to the general population. However, the risk of pre-disease was statistically significantly higher than that of the general population for all chronic disease groups. This can be interpreted as a powerful demonstration of the health worker effect among firefighters. Firefighters are a population of individuals who are physically and mentally very healthy at the time of employment, and this demonstrates the importance of occupational and environmental medicine-based health management to maintain the health of firefighters and alleviate their future burden of disease. The findings from this study provide actionable evidence for national and regional fire service organizations, occupational health policymakers, fire station medical staff, and public health agencies responsible for firefighter health and safety. Additionally, these results are directly relevant for researchers designing future cohort studies, managers planning workforce health interventions, and firefighters themselves seeking to understand their unique health risks. Insurance providers and occupational accident compensation schemes can also leverage these data to shape coverage, prevention policies, and support mechanisms for work-related disease. Based on the SPR findings, evidence-based recommendations for firefighter health management include: (1) implementing regular and risk-adjusted health screenings that specifically monitor pre-disease stages of chronic conditions such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome; (2) providing targeted exercise and fitness programs tailored to the physical and psychological demands of firefighting, with emphasis on aerobic fitness, musculoskeletal health, and cardiovascular risk reduction; (3) promoting nutritional education and lifestyle modification interventions to prevent progression from pre-disease to overt disease; (4) strengthening mental health resources and occupational stress reduction programs; (5) periodic review and improvement of workplace exposures (e.g., optimizing personal protective equipment, ventilation systems, and shift schedules); and (6) establishing a longitudinal health surveillance cohort to allow for ongoing monitoring and rapid intervention in emerging health risks.