1. Introduction

Indigenous Peoples are documented as effective stewards of their lands, with long-standing practices rooted in cultural traditions and relationships that sustain ecosystems for future generations [

1,

2]. One such approach is Indigenous Fire Stewardship (IFS), which involves the deliberate and controlled use of fire to care for fire-dependent ecosystems [

3]. Practiced for generations in central British Columbia (BC) by Indigenous Peoples, IFS uses low-intensity burns during cooler months to clean up grasslands and forests while reducing the buildup of hazardous fuels, and thereby lowering the severity, spread, and intensity of wildfires during peak fire seasons [

4,

5]. Beyond reducing wildfire risk, IFS promotes biodiversity [

6,

7,

8], supports habitat regeneration [

7,

9,

10], contributes to carbon offset [

11,

12] and bring social co-benefits [

13,

14]. IFS demonstrates a holistic approach to land care that integrates ecological, cultural, and climate benefits [

3].

As climate change intensifies, nature-based climate solutions are gaining popularity as a way to reduce emissions and restore ecosystems [

15]. Although nature-based solutions have been criticized by Indigenous scholars for its dissociation of nature and people, and the focus on natures’ role for society, its core idea still resonates with Indigenous Peoples’ way of life [

16]. In this context, Indigenous Peoples are increasingly recognized not only as rights-holders but also as key partners in designing and delivering these solutions, guided by their deep-rooted relationships with the land, knowledge, and longstanding stewardship practices [

17,

18]. One emerging pathway is through participation in carbon offset programs, where Indigenous-led land management—such as fire stewardship, reforestation, or conservation—can generate verifiable emissions reductions [

19,

20]. These efforts are often framed as “win-win” initiatives as they provide Indigenous Peoples with the opportunity to maintain or revitalize culturally grounded land-care practices while generating income through the sale of high-integrity carbon credits [

21]. Unlike extractive industries, these projects are conservation-focused, offering an alternative way to manage landscapes.

In British Columbia, the Great Bear Rainforest carbon project represents the only major Indigenous-led carbon project to date, primarily focusing on afforestation and avoided deforestation. Other types of capture-based carbon accounting are non-existent, which is the case for wildfire mitigation which has no established carbon accounting methodology to support fire-related mitigation strategies in Canada [

19]. As a result, the potential to generate carbon credits through fire-based approaches, such as IFS, remains largely unexplored. This is despite increasing wildfire risk across Canada, which disproportionately affects Indigenous Peoples [

22] and contributed 647 million tons of carbon emissions in 2023 [

23].

On the other side of the world, Australia’s savanna regions have pioneered the integration of IFS into their national carbon market. Russell-Smith et al. (2015) [

7] demonstrated that these IFS-carbon programs also deliver important cultural and social benefits to Indigenous Peoples (co-benefits), and evidence shows that participants in IFS exhibit better health and wellbeing outcomes [

24].

When comparing the Canadian and Australian contexts, Nikolakis et al. (2022) [

19] identified significant technical challenges in quantifying carbon offsets in temperate ecosystems, which have longer fire return intervals. More critically, they highlighted risks associated with conflicting worldviews in the development of these carbon credit programs, particularly if Indigenous engagement remains as its current level. For carbon credit frameworks to succeed—and to scale up as IFS gains public recognition as an effective wildfire mitigation strategy—they must be grounded in Indigenous Peoples’ perspectives and priorities (or cultural signatures).

Study Context

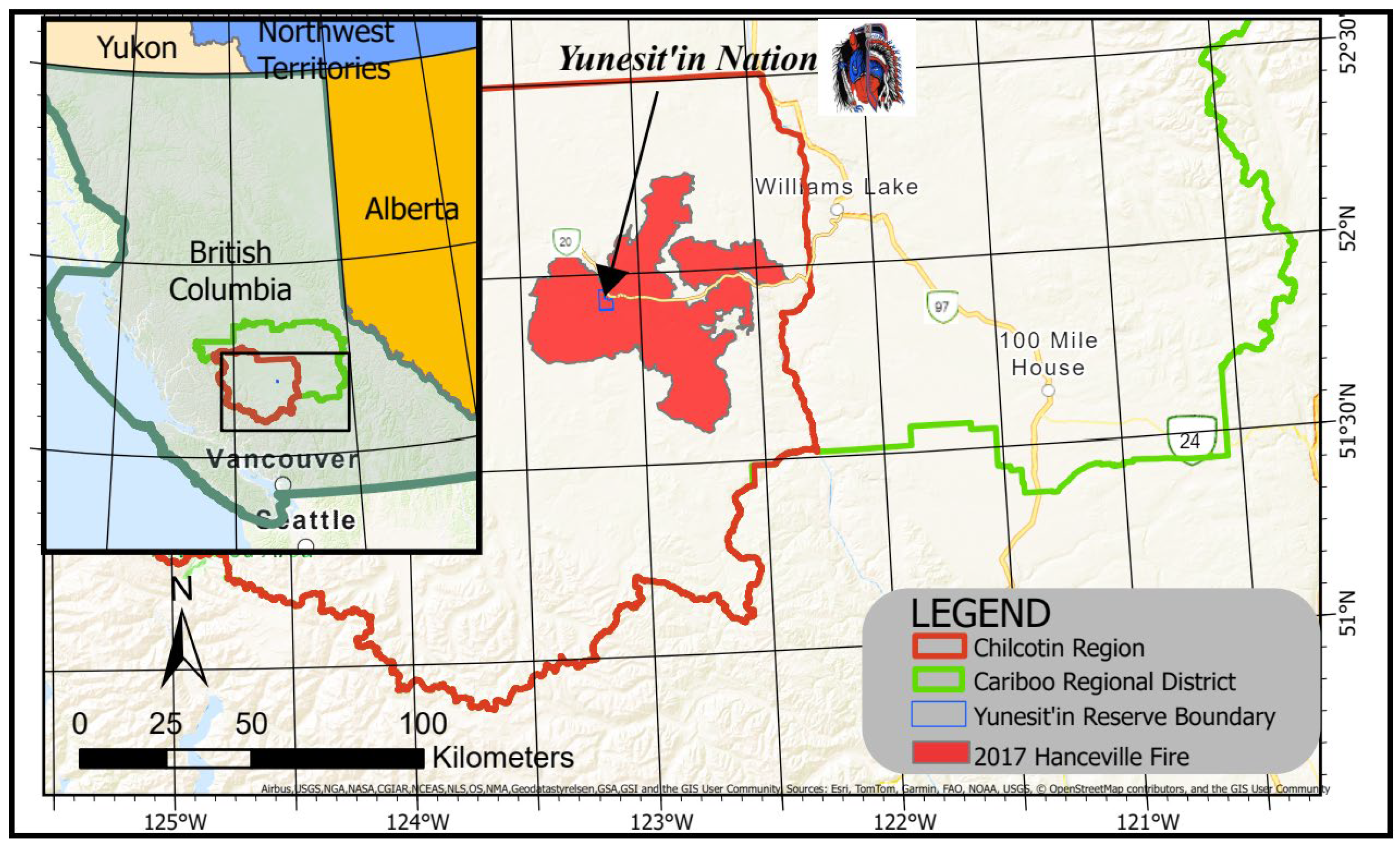

Yunesit’in, one of six communities of the Tsilhqot’in Nation, is located in the Chilcotin region of interior BC (See

Figure 1). Within the Biogeoclimatic zone classification of BC, the entirety of Yunesit’in’s reserve is located within an Interior Douglas-Fir Zone, described as an ecosystem with frequent stand-maintaining fires [

25]. As many other Indigenous Peoples in BC, the Tsilhqot’in were dispossessed of a large part of their ancestral territories and compelled into smaller reserve lands. The Tsilhqot’in Nation litigated and advocated for their lands back and were granted Aboriginal title in 2014, the first ones to get it in Canada, which restored 1700 km

2 of land. This provides the Tsilhqot’in Nation exclusive ownership to some of their lands and jurisdiction, including the ability to practice IFS.

From oral history, we know that the Tsilhqot’in have used fire (

Qwen) to manage their landscape for centuries [

5]. Despite this, the practice of using fire was criminalized for much of the 20th century, resulting in fuel build-up and woody species encroachment into grasslands [

26,

27]. In early 2017, the reactivation of IFS was identified by their Elected Chief (and co-author of this paper), Russell Myers Ross, as part of broader land stewardship goals. However, before these plans could be implemented, the community was severely impacted by the 2017 Plateau fire complex, one of the largest wildfires in British Columbia’s history [

28]. This fire devastated large portions of Yunesit’in’s traditional territory (see

Figure 1), sparking the start of the Yunesit’in IFS program in 2018. The subsequent report, The Fires Awakened Us: Tsilhqot’in Report on the 2017 Wildfires [

29], documented both the material and cultural impacts of the fire and became a powerful statement of the community’s resolve to restore ancestral burning practices.

The Yunesit’in IFS program is a partnership with Gathering Voices Society and the Firesticks Alliance. It applies cool fire during early spring and late fall and focuses on a hands-on, experiential learning approach for community members [

5]. Their vision has been expressed through three pillars: (1) to strengthen cultural connection & well-being, (2) to restore the health of the land (

Nen), and (3) to respect traditional laws, including caring for the land and taking responsibility for it [

30]. The program has been successfully running yearly since 2018 and has applied cool burns to more than 1500 hectares on their traditional territories. One core goal of the program is financial sustainability, which currently relies on public and private funding. As a sustainable source of revenue, the program managers have proposed exploring the feasibility of generating and selling carbon credits from their IFS activities as a mean of gaining long-term stability [

19].

Inspired by the success of Australia’s savanna projects, Yunesit’in is asking whether and how a carbon credit framework could align with their vision of bringing fire back to the land, but in ways that affirm their cultural and social priorities. This study is part of that inquiry. Rather than assessing carbon offsets from a strictly technical or policy lens, we approach the question from within the worldview of Yunesit’in practitioners. Our goal is to understand how carbon credit programs are understood by practitioners and how they think it can best support their IFS program.

Drawing on the concept of ‘cultural signatures’ coined by Jackson et al. (2017) [

31] in their analysis of savanna burning programs in northern Australia—those essential principles that must be reflected in program design—we examine two key dimensions: (1) the level of understanding among Yunesit’in fire practitioners of carbon credits, and (2) the cultural values and practices they see as non-negotiable in shaping a future carbon program. In doing so, we aim not to prescribe a model, but to support the creation of a path forward based on community priorities.

2. Literature

Although early emissions trading theories started in the 1960s, the foundation for compliance carbon markets was laid out with the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, which introduced emissions trading as a global mechanism to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The compliance carbon markets, mainly focused on large emitters in the energy and industry sectors [

32], have evolved in parallel with the voluntary carbon markets which sought to satisfy corporate self-imposed emissions goals—both market types taking root in early 2000s and evolving to what we have today.

Carbon markets aim to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions by commodifying carbon through the creation of tradable units known as carbon credits. These markets represent a philosophical shift in climate policy—from regulatory enforcement (“the stick”) to market-based incentives (“the carrot”)—positioning carbon reduction as an economically motivated choice rather than a mandated obligation. Developed largely within Western scientific and economic frameworks [

33], carbon credits systems isolate carbon emissions as the central cause of climate change through the greenhouse gas effect [

34].

This logic effectively abstracts carbon from its local socio-ecological context by framing it as a technical issue to be managed, which creates assumptions about ecosystems, human-nature relationships and economic valuation [

35]. However, this conceptualization of carbon is not universal; many Indigenous Peoples conceptualize climate change and environmental responsibility in ways that diverge from Western emissions-centric models [

36,

37]. As a result, the concept of carbon becomes a social construct shaped by dominant values, norms and power structures, many of which have been insufficiently questioned, rather than objective truths [

38]. This social construction can be considered continued imperialism, and is at odds with the Indigenous concept of Land as an entity that is alive, has agency, and is more than the sum of its parts (e.g., carbon) [

16].

These indigenous worldviews are not reflected in Canadian carbon credits systems as Indigenous Peoples have been excluded from the design and early implementation of both compliance and voluntary carbon markets [

39]. Colonial legacies continue to influence ownership, funding access, and trust, while barriers such as high costs, limited capacity, and technical complexity further restrict participation [

39,

40]. Carbon policies—often rushed in the name of urgency—frequently overlook Indigenous governance systems and treat Indigenous Peoples as stakeholders rather than full partners [

39,

41]. This top-down ‘push’ of Western carbon logics onto Indigenous Peoples undermines policy legitimacy, effectiveness, and justice [

39,

42].

Carbon credits have come under increasing criticism, often described as a “license to pollute” or a form of “greenwashing” that enables companies and states to claim net-zero targets without real emissions cuts [

43,

44]. Some critics go further, framing carbon markets as a new form of colonialism, where wealthy countries offload their emissions onto poorer nations without meaningful reductions [

20,

45]. While carbon schemes are sometimes presented as pathways to Indigenous empowerment, they have, in some cases, undermined sovereignty through external control, lack of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC), and the imposition of foreign environmental priorities—echoing historical patterns of exploitation and resource extraction [

20].

Despite these conflicts and challenges, Indigenous Peoples in Canada have shown eagerness to engage in such schemes, viewing them as opportunities to strengthen land rights and prioritize stewardship goals over market imperatives [

46,

47]. Their long history of adapting to environmental change and maintaining deep ecological knowledge positions them as key actors in climate mitigation and adaptation efforts [

18,

48]. While the province of BC introduced Atmospheric Benefit Sharing Agreements (ABSAs) to enable First Nations to generate and sell carbon credits, these agreements fall short of recognizing full carbon ownership [

19], and only 14 of 203 Nations have signed ABSAs since they came into effect into 2015—all tied to the Great Bear Rainforest carbon project. The project, based on a province-developed methodology, mitigates a yearly estimate of 1 million ton of CO2e over its 6.4 M hectares of stewarded land. Part of BC’s compliance market registry, the program struggled with large amounts of unsold credits, as the cap-and-trade system it was designed for never took off and buyers preferred larger, established registries [

49].

In contrast, Australia has seen notable success in integrating Indigenous fire practices into its carbon market over the past two decades [

7,

50]. This has revitalized traditional burning practices where Indigenous Peoples lead early dry season fires to avoid emissions from late dry season fires, mitigating against the emission of 14.5 million tons of carbon and resulting for substantial economic returns for the 72 project proponents [

51]. Jackson & Palmer (2015) [

52], documented that, unlike in Canada, there was an exchange between the government, scientists and Indigenous Peoples during the development of the formalization of a Savanna Burning methodology. This may explain the success of the program, as Indigenous Peoples were able to design and shape these frameworks to reflect their philosophy of care.

Jackson et al. (2017) [

31] coined the term “logic of care” to describe the desire to move away from the urge to optimize, control and model nature, and instead focus on the responsibility felt by Indigenous Peoples to care for their lands. Through that lens, the restoration of traditional stewardship practices is critical, and—as a mean to an end—carbon markets are considered the largest renewal opportunity in history [

31].

Carbon projects grounded in this logic display “cultural signatures” that reflect indigenous values and have proven critical to local acceptance and long-term viability, even enhancing their market value and attractiveness [

31,

53]. In Australian IFS projects, these cultural signatures manifest as the reactivation and intergenerational transfer of knowledge, strengthened community empowerment, and renewed connections to ancestral lands—benefits that extend well beyond carbon and are anchored in locally meaningful narratives [

31].

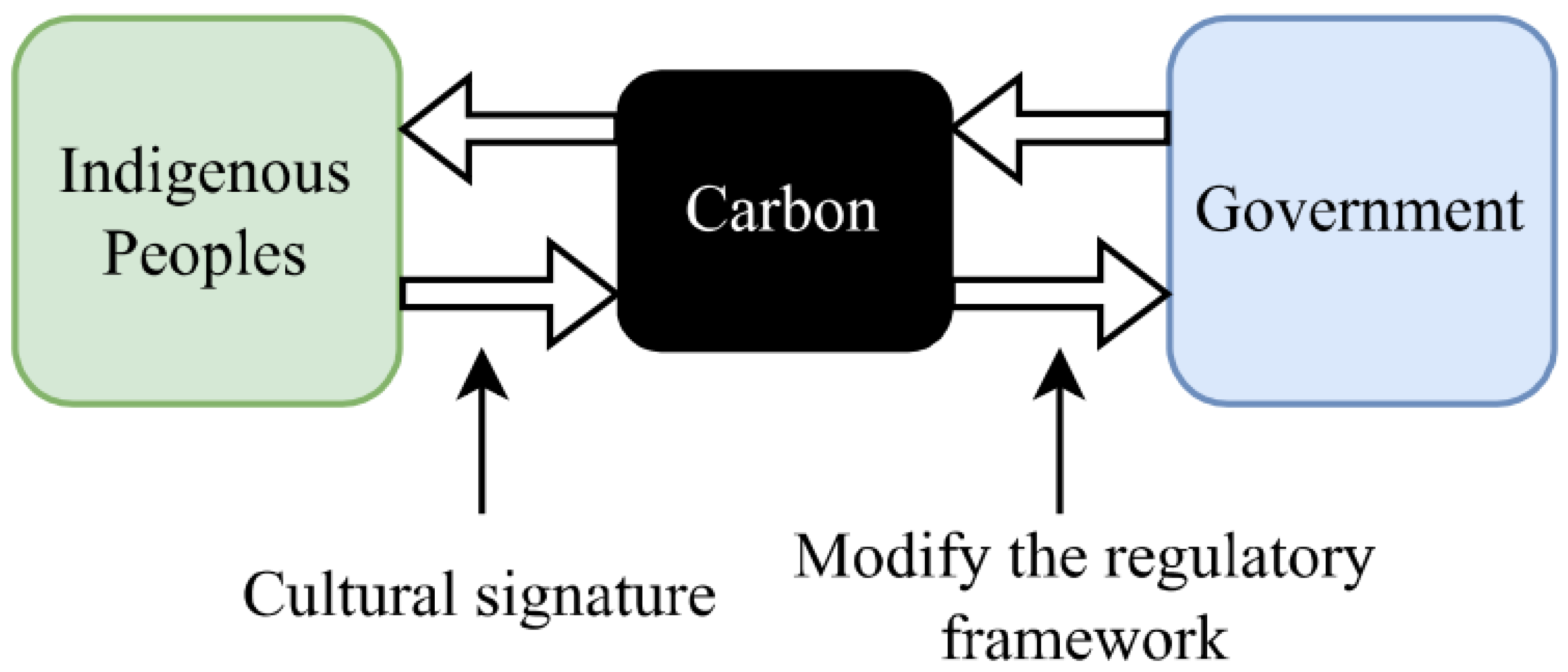

A cultural signature reflects how a community defines good climate action—not necessarily through technical expertise, but through lived relationships with land, each other, and change. Even where understanding of carbon credits may be limited, community members can articulate what ethical, grounded stewardship looks like. These signatures demonstrate how deeper engagement may be critical to create carbon policies that lead to successful carbon projects. As carbon economies evolve, Indigenous participation is not simply reactive but transformative. This exchange challenges the idea that policy only flows from government to Indigenous Peoples. Instead, it suggests a two-way process where Indigenous engagement—if their ways of thinking are truly understood—may ultimately lead to a more just, culturally sensitive, and ecologically grounded carbon future, one that could have emerged if Indigenous Peoples had been involved in the creation of carbon markets from the outset (see

Figure 2). Such engagement also opens the door for communities to strengthen a renewed sense of purpose through stewardship activities.

3. Methods

The research was conducted on the unceded and traditional territory of the Tsilhqot’in Peoples. All research activities were reviewed and approved by Russel Myers Ross, co-author of this paper and Yunesit’in scholar.

We employed a qualitative methodology, conducting interviews using a grounded theory approach to guide data collection and analysis. This methodology was chosen because our research questions center on how individuals experience, interpret, and navigate carbon markets and IFS in a specific cultural context. Qualitative research is particularly well-suited to capturing these complex social, cultural, and political dimensions—insights often inaccessible through quantitative methods. Grounded theory, a non-linear and iterative approach, allows theory to emerge inductively from the data, reducing the influence of researcher bias in shaping hypotheses or interpreting findings [

54]. Documenting lived experiences and Indigenous knowledge systems was central to our study.

To explore the level of understanding of carbon credits and cultural values of Yunesit’in fire practitioners, we identified five overarching topics relevant to a potential IFS–carbon program: the existing IFS program, Land and worldviews, climate change, money, and carbon credits. Interview questions were developed around these topics (See

Appendix A).

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in May 2024 with ten Yunesit’in community members who were directly involved in or knowledgeable about the IFS program (see

Table 1). Interviewees were selected using a purposive sampling approach, based on their knowledge and experience of the IFS program. As such, two groups from the Yunesit’in community were approached, fire practitioners, and community leadership. We employed a total population sampling strategy for fire practitioners (N = 20), interviewing all who were available and willing to participate during the fieldwork period. For community leadership, we employed an expert sampling strategy and identified five community leaders to approach. A total of 25 community members were approached to participate, through personal connections or a community liaison, and 10 agreed to be interviewed, all from Yunesit’in.

Seven interviewees were current fire practitioners, while three held leadership roles within the Yunesit’in government (

Table 1). This sampling strategy prioritized depth of insight and contextual understanding over statistical generalizability, aligning with the goals of grounded theory and qualitative inquiry.

The interviews, lasted on average around 45 min and were held at a location convenient for interviewees, and followed a semi-structured, conversation-style interview [

55], where both the interviewer and interviewee could ask questions. If the interviewee did not understand a concept, it was explained to them by the interviewer. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and transcripts were generated and offered for validation to the interviewees [

56]. The interviews were anonymous and no personal information was recorded. An iterative thematic analysis was done using NVivo 14 to identify emerging themes coming from individual statements, and were then aggregated into larger key themes [

57].

Building on the initial thematic analysis, we conducted an additional literature review to deepen our understanding of carbon as a social construct and the intercultural exchange between Indigenous Peoples and governments/states. This additional literature review guided the formulation of the conceptual framework of the exchange happening using “cultural signature” to modify the regulatory framework.

4. Results

4.1. Level of Understanding of Carbon Credits

For the interviewees, climate change is a deeply felt reality—visible not through scientific graphs or emissions data, but through lived experiences on the land: “Yeah, I honestly don’t know much about climate change. I just go by what I see on the land” [interviewee 5], and this was echoed by three others.

Across the interviews, everyone spoke of shifting seasons and unusual temperature extremes. “It’s impacting our weather system, it’s impacting our winters” [interviewee 1], while another noted, “We didn’t have much snow this year” [interviewee 3]—this was mentioned by nine out of ten interviewees. Others reflected on the growing severity of wildfires and the intensity of summer heat. These observations signaled a profound awareness that things are changing in negative ways.

When discussing who or what is responsible for these changes, interviewees pointed to large corporations and poor land management practices like mining and deforestation. “Back then there wasn’t as much devastation to the land as there is today” [interviewee 4] one person reflected, linking environmental degradation to modern development and consumption. Only one person mentioned carbon as a contributing factor, while four referred to pollution.

Despite this concern, there was also a sense of resignation. Five shared the belief that “there’s not much you can do about climate change” [interviewee 5]. Instead, they gravitated toward a more grounded, immediate response: “To have beneficial effects on the climate, we have to take care of the land more” [interviewee 6]. The idea was simple but powerful—if we take care of the land, the land will take care of the climate because “both of those are connected” [interviewee 9].

When it came to formal climate solutions like carbon credit markets, understanding was minimal. Six out of ten interviewees admitted they did not know what a carbon credit was. One mistook it for a carbon tax, while the others had only a vague familiarity with the term, saying things like, “I might have an idea,” [interviewee 6] or “I’ve heard of it, but not too much” [interviewee 1] before declining to elaborate.

Yet, even without deep knowledge of policy mechanisms like carbon credits, interviewees offered a rich, alternative perspective rooted in land, tradition, and observation. Their voices call for a climate response that is less about abstract markets and more about relational stewardship—about being on the land, noticing the changes, and responding with care and responsibility.

After carbon credits were explained to them (see

Appendix B), all ten interviewees expressed support for the idea. One participant reflected, “That’s a really good plan” [interviewee 9] referring to the potential of “getting money for it to keep this program alive” [interviewee 2]. This reflects an indirect support, where carbon credits are a means to achieving an end.

4.2. Cultural Signatures

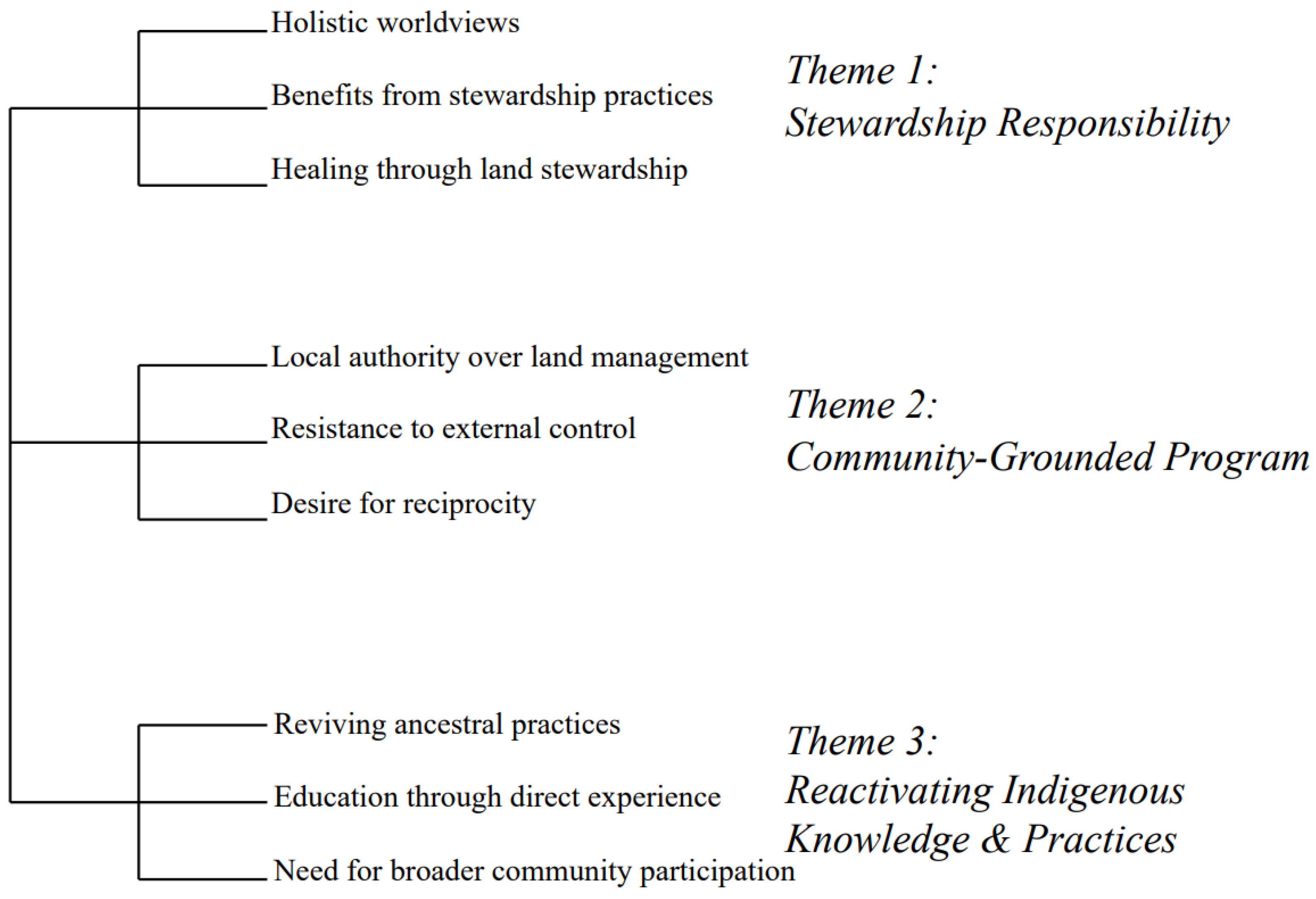

Nine codes related to foundational principles to be reflected in carbon credit frameworks have been identified from the interviews. The codes have been further grouped into the themes forming the different cultural signatures (see

Figure 3).

4.2.1. Stewardship Responsibility: Multiple Benefits

For all ten interviewees, land stewardship through IFS is not just a technical task or a climate strategy—it is a sacred responsibility, one that flows from generations of living with and learning from the land. Their approach to land care is grounded in a worldview where “the river, the rock, the tree, the ground, I feel like everything is connected. Everything’s alive” [interviewee 9].

“We can help it, we can take care of it, we can let it regrow” [interviewee 3] one participant said simply, summarizing a relationship built on reciprocity, not extraction. “That’s why we’re land caregivers” [interviewee 1] another added, using a term that speaks to a role far more intimate than ‘land manager’ or ‘carbon offset planner.’

This responsibility is not abstract or distant—it is rooted in cultural practices, community well-being, and direct observation of the land’s condition. As one participant explained, “If you are healthy, you want to take care of the land. If the land is healthy, it will take care of you” [interviewee 7]. This reciprocity frames the land not as a carbon sink, but as a living relative—one whose health is intertwined with their own.

In contrast to carbon credit markets, which typically focus narrowly on emissions avoided, the interviewees believed in a broader, more holistic set of benefits from stewarding their lands. They spoke of IFS not only as a climate solution, but as a path toward healing their land, community, and individuals: “The cultural burning, I feel like it opened my eyes. It refreshed my memory on how good it feels to start taking care again. To take responsibility for doing things that the land needs and our people need” [Interviewee 9].

Wildfire mitigation was one immediate outcome they pointed to. IFS was seen as both protective and regenerative. “It will protect our people in our community” [interviewee 9] one said. “It’s a lot greener when the rain comes around after we burn like that” [interviewee 5] added another, describing the visible signs of ecological renewal.

Food security was another crucial benefit. Interviewees noted the return of traditional food sources—from berries to wildlife—as the land was tended more intentionally. “I’ve noticed some berries were coming back” [interviewee 6] “We’ve seen more wildlife coming back, way more wildlife” [interviewee 1]. These changes were not just ecological; they were personal, and related to survival and personal health: “We live off the meat that we get when we go hunting” [interviewee 3] one person explained.

There was also a strong link made between stewardship and individual well-being. Many described how engaging in stewardship helped their physical and mental health. “I can feel it in my health” [interviewee 7] one participant said. “All the exercising I’ve been doing definitely helped me reconnect with mother nature” [interviewee 6]. For others, being on the land reduced stress and brought peace. “You just kind of let it go when you’re out on the land” [interviewee 9].

Beyond individual wellness, there were economic and social benefits too. Stewardship work offered meaningful employment and a chance to strengthen community cohesion. “Not only that, [the land] is a workplace for our members” [interviewee 1] one person shared. Others emphasized the importance of continuing the program, not just for the environment, but for livelihoods: “It helps them to get off social assistance, putting more people to work, bring the community together” [interviewee 2].

4.2.2. Community-Grounded Program

For the Yunesit’in fire practitioners, true stewardship is not something that can be outsourced, regulated from afar, or reduced to policy checklists. It is an inherent relationship—rooted in care, knowledge, and accountability to the land—that must remain in the hands of the people who live on and depend on it. As such, all participants expressed a clear desire to keep their program independent.

Interviewees consistently emphasized that land management must be led locally. “Land management should be local,” [interviewee 7] said one participant, “driven by our community members or nation. It shouldn’t be the government” [Interviewees 2]. Another added plainly, “The locals know best the right decisions to make” [Interviewee 1]. For many, effective stewardship is inseparable from the lived relationship with the land. Several interviewees described how external interference, particularly from government authorities, disrupts traditional practices. “We still could be burning, but there’s fire ban, and then there’s a government stopping us to burn,” one noted [Interviewee 7], echoing a frustration shared by half the interviewees. They made clear they don’t just want a seat at the table—they want to be the ones setting it. Stewardship, in their view, must come with ownership and authority: “We should have more responsibility over our land and how they use it.” This is not about seeking permission, but about reclaiming the right to carry out the responsibilities passed down by their ancestors.

This perspective extends to conversations around carbon credits. While interviewees were open to participating in these markets, they were also wary of outsiders who see only carbon and not the people, culture, and history behind the stewardship. It must be relational, not just transactional: “If someone is interested in buying the carbon credits, they need to be interested in what we’re doing. Maybe they should come to the table, and sit down and talk” [interviewee 1].

4.2.3. Reactivating Indigenous Knowledge and Practices

At its heart, IFS is about restoring the ancestral knowledge and cultural practices that were forcibly interrupted by colonization and residential schools. It’s about remembering how to “look after the land, like our ancestors did” [interviewee 4].

Interviewees spoke of fire not only as a tool but a way to re-learn practices that were impacted by colonialism—a cultural resurgence. They acknowledged that much has been lost over the years—practices and wisdom that once maintained healthy, balanced ecosystems have faded from collective memory. As one participant reflected, “Doing this type of traditional burning, it’ll help us open our eyes onto more of what our ancestors used to do to keep the land strong” [interviewee 4] Another added, “The culture was kind of lost because you noticed that it hasn’t been done for a long time” [interviewee 9].

The barriers imposed by the government continue: one participant expressed frustration saying, “Then the government comes in, changes it around, puts all these bans… stopping what we know as a community. You know?” [interviewee 7]. This statement reflects that bringing IFS back is contested as it challenges power around who decides what happens on the land.

The path to renewal, they emphasized, is collective. Reviving IFS requires community-wide participation. “We need more people to be able to do it” [interviewee 4] one said. “If it’s just a couple of us, it’s going to happen really slowly. If we work as a community, it would just be that much faster” [interviewee 2] Another echoed the sentiment: “Some of our people need to come together and join us in taking care” [interviewee 1].

Yet, bringing the community along is not without its challenges. For many, the trauma of recent catastrophic 2017 wildfires have left a lingering fear of fire. “A lot of people were and are still scared of fires…” [interviewee 1] one participant noted. This fear has become a barrier to fully embracing IFS again, but one that continued practice helps overcome: “…to experience it firsthand and give[s] them a sense, [the] right idea, how this benefits so much” [interviewee 6] one said. Others voiced optimism that with time and exposure, people would “see what we saw” [interviewee 4]. This adds a layer of complexity as perspectives and support may change over time—a process that already started.

5. Discussion

These findings highlight a layered understanding of climate change among the interviewees—one based on lived experience of ecological change, not in abstract carbon emission value. While awareness of carbon markets was limited—six out of ten interviewees had little or no familiarity—this is unsurprising given the minimal engagement of Indigenous communities in BC in the development and design of carbon markets

Yet this lack of technical knowledge did not mean disengagement. When carbon credits were explained, all ten interviewees supported them—not because of carbon per se, but because of what such programs could enable: sustained long-term stewardship by generating income every project cycle. Their endorsement was practical and conditional—carbon credits were seen as a potential means to achieve more lasting outcomes for their IFS program, not an end in themselves. However, the question of whether carbon markets can provide stable long-term income remain uncertain. Uncertainties from these rapidly evolving markets suggest that carbon revenue should be viewed as a funding mechanism while long-term stability must be grounded in effective governance.

Effective governance connects directly to a deeper theme that emerged across the interviews: stewardship as a lived responsibility. Interviewees were not simply advocating for land management—they were asserting a worldview in which care, connection, and responsibility to land are central. “We can help it, we can take care of it, we can let it regrow” [interviewee 3] as one said. This comes from a desire to rebalance the reciprocal relationship with the Land (

Nen) [

16].

Interviewees described climate change as altered weather patterns, reduced snowfall, and intensifying wildfire, not as climate science, but as tangible disruptions to the rhythms of land they know intimately: “I just go by what I see on the land” [interviewee 5]. This affirms that the Indigenous understandings of climate are built on lived relational ecological experience and pattern recognition rather than abstract scientific modeling [

37,

53].

IFS is thus framed as a way to take control and agency over a changing climate—shifting their role from being passive to active actors: “it feels good to start taking care again” [Interviewee 9]. In Yunesit’in, the return of berries and wildlife, the physical and mental well-being gained from being on the land, and the simple joy of shared labor are all part of what makes IFS meaningful. These are not ancillary outcomes—they are the outcomes.

However, these goals may be clouded by other pressures associated with the carbon markets like meeting emission reduction targets and their associated revenues. For example, the ALFA program in Australia faced criticism from traditional landowners when aerial incendiary techniques was used (incendiary bombs dropped from helicopters)—justified by the leadership as a reality to manage a large area—and seen by traditional owners as disconnected from traditional practice and understanding [

50]. Similarly, examples of professionalization and bureaucratization of IFS projects have at times displaced traditional owners and eroded Indigenous control where some rangers mention that they only do what they are being told [

58].

Similar tensions are emerging in Canada, where formalization of a profession risks hybridizing Indigenous knowledge to fit within dominant models [

59]. If carbon projects are reduced to the logic of offsets, important cultural and ecological co-benefits risk being sidelined [

14].

To honor this, evaluation metrics must go beyond human-centric and economic goals of carbon sequestration to include community-defined indicators of success—based the relationship between humans and nature. Statements like “I feel healthier doing this work” [interviewee 10] and “we’ve seen more wildlife coming back” [interviewee 1] offer meaningful qualitative insights. Integrating visual documentation, storytelling, and community-led monitoring can preserve accountability while respecting Indigenous knowledge systems. Capturing co-benefits is essential for legitimacy and longevity [

14], particularly in voluntary markets where cultural and ecological value can drive premium pricing [

19].

Another core finding from the interviews is the central importance of having a community-grounded program—allowing control over decisions, timing, methods, and engagement: “Land management should be local, driven by our community” [interviewee 3]. Others spoke with frustration about government interference: “Then the government comes in, changes it around, puts all these bans… stopping what we know as a community” [interviewee 7]. These quotes speak to a history not just of exclusion but of imposition. They echo literature warning against top-down approaches that marginalize Indigenous Peoples in climate governance [

46,

60]. Trust, transparency, and consensus-building are all foundational to Indigenous models of decision-making [

61], which do not seek uniformity but respectful dialogue and shared direction. This will only work if self-determination and the colonial legacy of these Nations are recognized [

16,

62,

63].

Supporting this local autonomy is not simply a matter of ethics—it is essential for program success through decisions, management and practice. Research has shown that Indigenous-led projects are more likely to be effective when communities retain ownership and governance [

64,

65]. Yet retaining this control often hinges on financial independence and institutional flexibility. Programs burdened by conditional funding or prescriptive technical requirements risk alienating the very communities they aim to empower. Here, the voluntary market presents an opportunity: it allows for more adaptable methodologies and the potential for revenue models that do not undermine Indigenous priorities if safeguards/Indigenous worldviews are respected in their design—like the ALFA—which Altman et al. (2020) [

50] analyzes.

From ALFA’s experience, this local autonomy is enabled through effective governance arrangements [

50]. ALFA’s participatory governance and corporate form allowed it to balance bottom-up community representation and top-down regulatory and market requirements. While support for carbon credits was widespread among interviewees, translating this interest into effective and sustainable programs requires more than community enthusiasm. It requires building governance capacity that can both promote IFS and negotiate carbon benefits, positioning the community to engage on their own terms. This will require leaders who can bridge Indigenous and Western systems (“two-eyed seeing”) that can advocate for the recognition of these cultural signatures. ALFA stand as an example that this is possible, but also as a reminder that these negotiations need to come from Indigenous Nations themselves, not from external validation. Strong Indigenous governance, however, cannot be separated from culture and must draw on and reinforce indigenous knowledge systems [

2].

Reactivating Indigenous knowledge and practices was another cultural signature identified. Among the Tsilhqot’in, knowledge systems are deeply rooted in observation, seasonal patterns, and embodied memory passed down through stories and shared practices [

61,

66,

67]. As one participant put it, “Doing this type of traditional burning, it’ll help us open our eyes to more of what our ancestors used to do” [interviewee 4]. IFS is not a fixed protocol, but a living, adaptive process grounded in relationship to place—nature-based solutions are also culture-based solutions [

16].Carbon methodologies must therefore move beyond rigid frameworks and accommodate this other knowledge system—ensuring they are not only scientifically robust but also culturally responsive and context-specific. Standardized carbon market approaches, however, often center technical metrics and externally defined protocols, sidelining Indigenous ways of knowing. Inflexible methodologies risk excluding youth, Elders, and others without formal training—individuals whose participation is vital for long-term stewardship and knowledge transfer [

39]. In this context, pluralism is critical. A one-size-fits-all approach risks flattening diverse cultural landscapes into carbon maps.

As voluntary carbon markets expand, they are beginning to attract Indigenous interest, but caution remains. Some communities reject market mechanisms entirely, skeptical of external control and commodification [

12]. Others, like Yunesit’in, express conditional support, seeing carbon funding as a tool—not a goal—for sustaining stewardship. As one participant put it, “That’s a really good plan… getting money for it to keep this program alive” [interviewee 9]. The deeper question is not whether carbon can support IFS, but how: Will funding structures allow for Indigenous co-design, uphold cultural values, and adapt to local conditions—or will they impose rigid frameworks that displace the very knowledge they claim to support? Can economic activities, including carbon trading, be done in a sustainable and respectful way as some Indigenous scholars dream of [

16]? Will there be a recognition that IFS pairs with forestry values instead of competing with it?

6. Conclusions

At its heart, Yunesit’in’s IFS program is not a carbon initiative. It is a cultural resurgence, a practice of care, and an act of relearning through practice. The Land (Nen), for many interviewees, is not a resource to be optimized but a living relation to be nurtured. Fire, in this context, is not just a tool of ecology—it is a language, a method of reconnecting, of rebalancing, of healing—it is also a teacher on how to view the land and oneself in relation to it. As one participant put it: “It’s about being on the Land and connecting with everything that keeps you alive” [interviewee 9]. This worldview cannot easily be reconciled with carbon markets that prioritize measurable emissions reductions and transactions over intangible, but no less vital, relationships, between people and the land. The challenge is not only technical—it is philosophical. While Western frameworks isolate carbon as the central metric of success, Indigenous frameworks embed carbon within a broader story of responsibility, reciprocity, and renewal. It is here that Yunesit’in’s IFS offers more than a local model—it offers a fundamental rethinking of what carbon credits could be.

Canada, at present, lacks a formal mechanism to recognize or reward this form of stewardship within its carbon accounting systems. And yet, this absence opens the door to innovation. A new methodology can be developed that accounts for good fire and its role for preventing fire-related emissions. Rather than seeing fire as carbon reversal in conservation projects, fire should be acknowledged as inevitable. Voluntary markets can provide a flexibility to this methodology, presenting an opportunity to do things differently—to build carbon programs not just for Indigenous Peoples, but from within their worldviews. But to do so, more than consultation is required. Structural shifts in governance, financing, and methodology are essential to reflect local cultural signatures. Such shifts must be grounded in bottom–up governance, with Indigenous communities retaining control over how programs are designed, led, and sustained. To safeguard them, programs need to nurture the participation of the elders and the youth, allow local knowledge to guide stewardship activities, and monitor co-benefits that reflect local values.

Carbon credits remain poorly understood by many Indigenous Peoples—reflected in this study—and the technical barriers to participation remain high. More efforts are needed to build shared literacy around what these programs entail—and to democratize decision-making in a way that allows Indigenous Peoples to set the terms of engagement. Without this, carbon markets risk reproducing the same extractive dynamics they claim to solve.

What we are witnessing, however, is not passivity but growing Indigenous agency. Yunesit’in is asserting leadership—not waiting for permission but creating space where Indigenous laws and values can guide environmental governance. It is this leadership that has the potential to influence regulatory markets. This shift is not yet embedded in policy, but it is visible—in legal advocacy, in land-based programs, in growing calls for accountability. These movements, while diverse, share a common thread: a refusal to be tokenized, and a demand for partnership built on respect.

This research contributes to that momentum, not by offering a blueprint, but by illuminating the cultural signatures that can help shape more just carbon credit frameworks. By looking from Indigenous worldviews toward Western systems—not the other way around—we begin to clear the space for genuine reciprocity. It is in these spaces that compromise becomes possible—not to compromise in the sense of giving something up, but in the older sense of promise together.

Yunesit’in’s cautious interest in carbon credits reflects a pragmatic hope—they see potential in these mechanisms to sustain land-based programs. But this interest is tempered by concern: that carbon markets may become yet another form of external control Indigenous communities must accommodate. This is precisely what people want to avoid. If we are serious about tackling climate change in partnership with Indigenous Peoples, then control over how climate solutions are designed, implemented, and measured must rest with them. These cultural signatures—stewardship responsibility, community-grounded programs, and the reactivation of Indigenous knowledge and practices—offer a pathway for doing so. They are not just values; they are design principles.

Yunesit’in’s efforts remind us that real change does not begin in boardrooms or markets, but on the ground—in forests while caring for their Land, people, and future generations. Carbon credits, if aligned properly, can become a means to support this end—but they must follow, not lead.