Analysis for Evaluating Initial Incident Commander (IIC) Competencies on Fireground on VR Simulation Quantitative–Qualitative Evidence from South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials

4. Methods

4.1. Study Framework

4.2. Quantitative Evaluation

4.3. Qualitative Communication Analysis

4.4. Integration of Findings

5. Results

5.1. Overall Candidate Performance

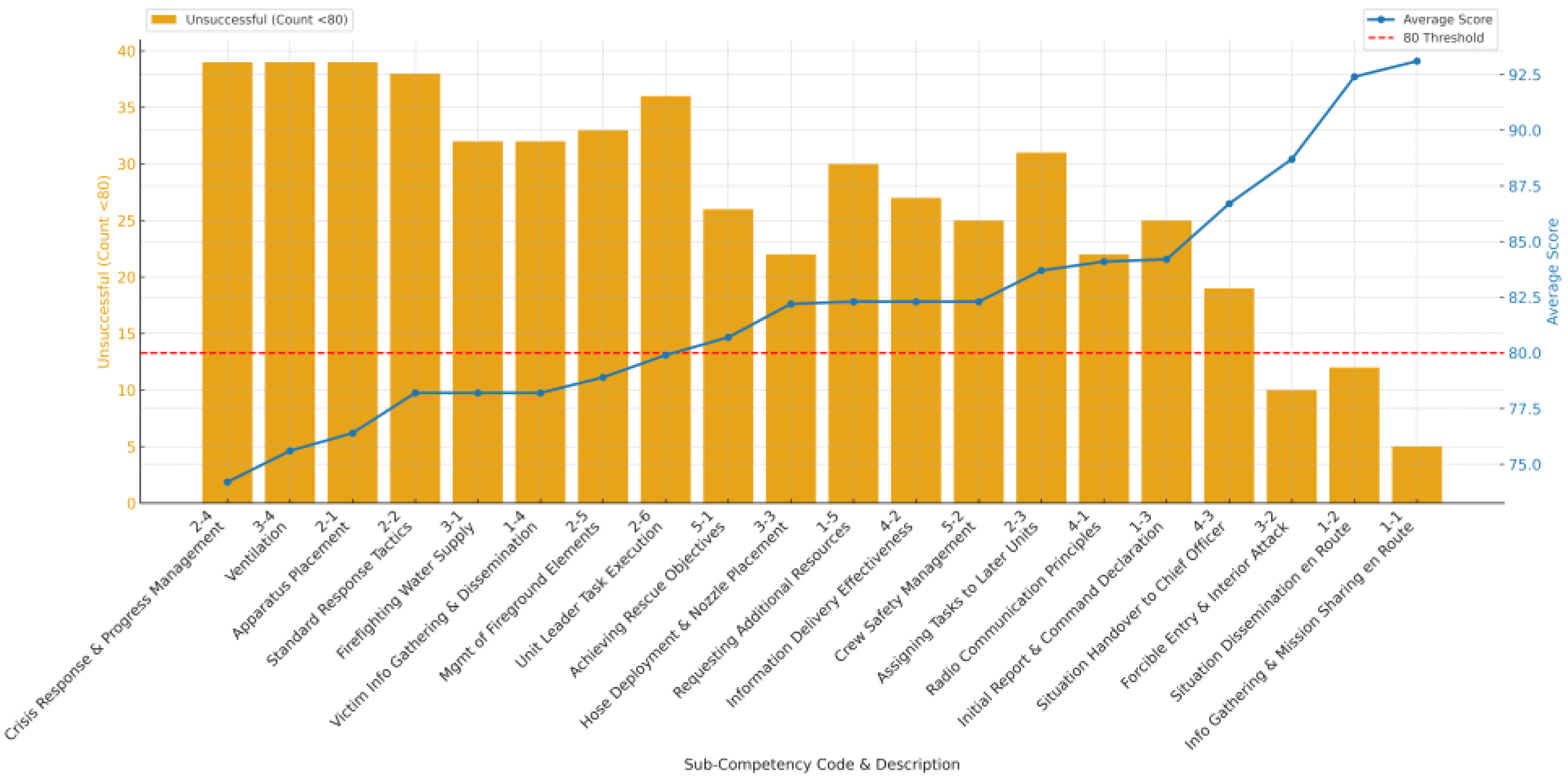

5.2. Sub-Competency Performance Breakdown

5.2.1. Highest Failure Sub-Competencies

5.2.2. Moderate Failure Sub-Competencies

5.2.3. Lower Failure Sub-Competencies

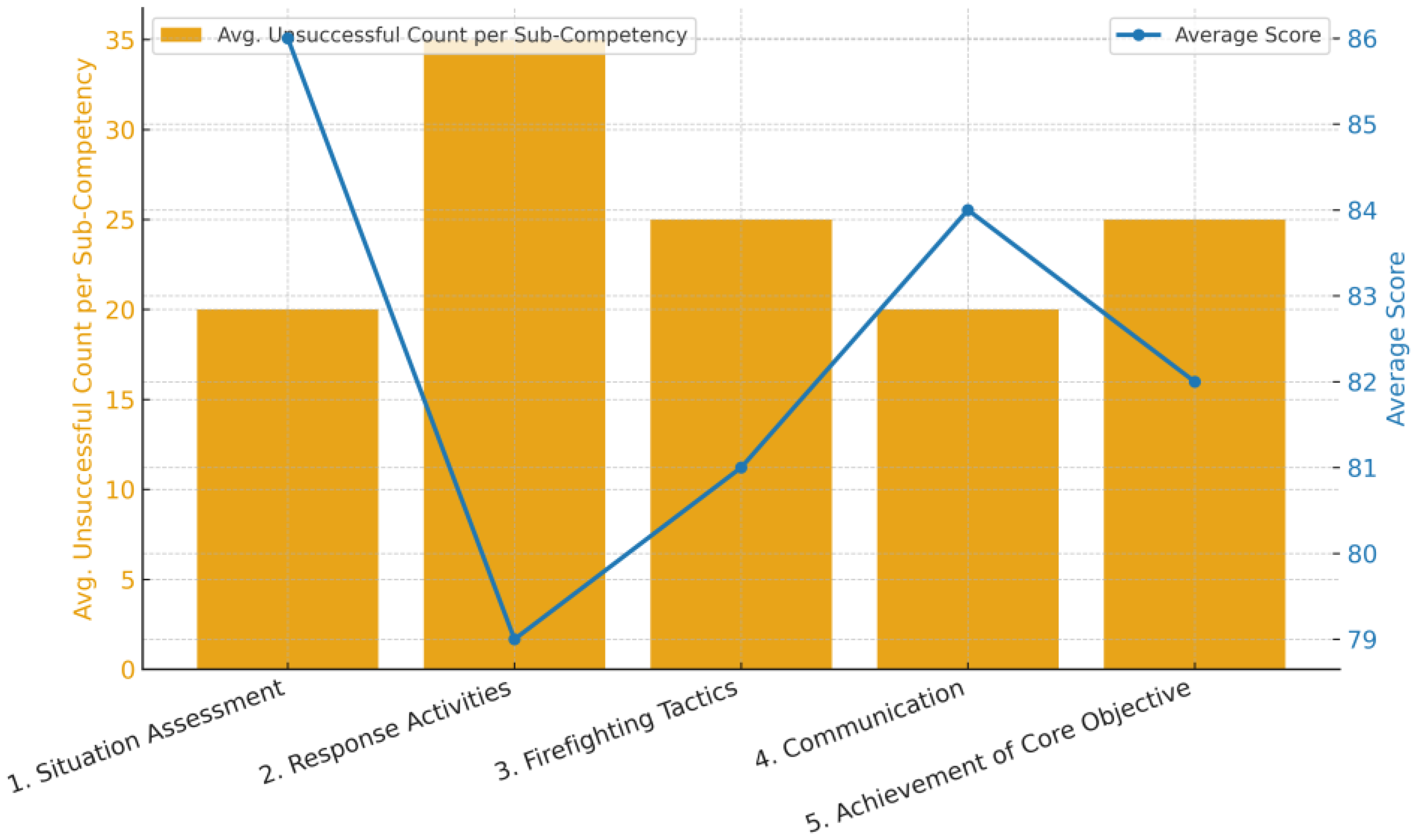

5.2.4. Domain-Level Patterns

5.2.5. Descriptive Statistics

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theorical Impications

7.2. Practical Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Evaluation Process for Initial Incident Commander Certification

| Random assignment of five types of virtual disaster scenario | ⇨ | Virtual Reality | ⇨ | Interview (Q&A) |

| On-Scence Command | ||||

| 5 min | 20 min | 5 min |

- Sequence & duration: Briefing (5 min)→VR On-Scene Command (20 min)→Q&A (5 min).

- Components

- On-scene command: Evaluates situation reporting, response activities, life rescue, and crew safety.

- Q&A: Provides additional assessment for competencies not fully verified during the VR segment.

- Evaluation indicators: 5 evaluation areas comprising 20 behavioral indicators in total.

- Pass criteria: A candidate passes with a total score of 80/100 or higher and no “Low” rating on any key behavioral indicator from two or more assessors.

- Assessor/Evaluator Procedures & Adjudication. Each evaluator scores independently using the standardized rubric. For ★ Key Indicators, a narrative justification is mandatory whenever a Low rating is assigned. If two or more evaluators assign Low on any ★ indicator, the candidate automatically failed regardless of other scores. Such cases are re-reviewed in a panel consensus meeting to confirm rationales, ensure scoring integrity, and finalize the outcome. Adjudication notes (rationale, time stamps, final decision) are recorded and archived with the candidate’s evaluation record.

Appendix A.2. Assessment Criteria and Behavioral Indicators

- For any “Low” rating, the assessor must clearly state the reason, emphasizing its importance and implications for field command.

- Record detailed opinions on the candidate’s judgment, communication clarity, tactical command, and leadership qualities.

- Specifically describe areas where the candidate showed difficulty or hesitation and provide opinions that can assist in future training and improvement.

- When a criterion is rated Low, the evaluator must record a specific, behavior-anchored reason (what was observed, when, and its operational impact).

- For ★ Key Indicators, a reason for any Low rating is mandatory. If two or more evaluators assign Low, the candidate is automatically failed; such cases are re-discussed in a panel consensus meeting, and the final decision is documented.

- Provide comprehensive comments on overall strengths and areas requiring improvement.

- These comments will be included when notifying individual results and serve as primary feedback. Please provide constructive remarks that can help the candidate improve capabilities.

| Evaluation Category | Behavioral Indicators | Score High | Mid | Low | Observation & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Situation Assessment | 1-1 Information Gathering & Mission Sharing en Route | H(3) | M(2) | L(1) | |

| 1-2 Situation Dissemination en Route | H(3) | M(2) | L(1) | ||

| 1-3 Initial Situation Report & Command Declaration ★ | H(10) | M(7) | L(4) | ||

| 1-4 Victim Information Gathering & Dissemination | H(5) | M(3) | L(1) | ||

| 1-5 Requesting Additional Resources | H(3) | M(2) | L(1) | ||

| 2. Response Activities | 2-1. Apparatus Placement | H(5) | M(3) | L(1) | |

| 2-2 Standard Response Tactics | H(5) | M(3) | L(1) | ||

| 2-3 Assigning Tasks to Later-Arriving Units | H(3) | M(2) | L(1) | ||

| 2-4 Crisis Response & Progress Management | H(5) | M(3) | L(1) | ||

| 2-5 Identification & Management of Fireground Elements | H(5) | M(3) | L(1) | ||

| 2-6 Unit Leader Task Execution | H(3) | M(2) | L(1) | ||

| 3. Firefighting Tactic Skills | 3-1 Firefighting Water Supply | H(5) | M(3) | L(1) | |

| 3-2 Forcible Entry & Interior Attack Initiation | H(5) | M(3) | L(1) | ||

| 3-3 Hose Deployment, Water Application & Nozzle Placement | H(5) | M(3) | L(1) | ||

| 3-4 Ventilation | H(5) | M(3) | L(1) | ||

| 4. Communication | 4-1 Radio Communication Protocols | H(5) | M(3) | L(1) | |

| 4-2 Information Delivery Effectiveness | H(5) | M(3) | L(1) | ||

| 4-3 Situation Handover to Arriving Chief Officer | H(5) | M(3) | L(1) | ||

| 5. Achievement of Core Objective | 5-1 Effectiveness in Achieving Life-Safety Objectives ★ | H(10) | M(7) | L(4) | |

| 5-2 Crew Safety Management | H(5) | M(3) | L(1) |

Appendix A.3. Certification Eligibility, Methods, and Evaluation Panel

| Eligibility | Applicants must be IICs’ with at least one year of field experience | ||||

| Evaluation Method | Simulated disaster scenarios will be used to evaluate IICs’ capabilities. ※ Fire, explosion, and hazardous material accidents are simulated; scenarios may be adjusted to match the candidate’s real-world experience and rank. 1. Grant situational authority and responsibilities based on the scenario. 2. Assess the individual’s abilities through interviews on the commander’s decisions and response strategies. 3. Draw one of the five simulated disaster environments by lot before the evaluation begins. 4. Independent scoring: Each evaluator completes all ratings independently using the standardized rubric (H/M/L mapped to percentage). 5. Low-on-★ protocol: Any Low on ★ indicators requires a written rationale; if two or more evaluators assign Low on any ★ item, the candidate is automatically failed. 6. Consensus meeting: Following independent scoring, evaluators convene to review Low-on-★ cases, confirm rationales, and finalize the decision (pass/fail). 7. Documentation: The panel chair records adjudication notes (items discussed, final decision, time) and attaches them to the candidate’s evaluation record. | ||||

| Evaluation Panel | At least 3 evaluators for the practical exam and 3 or more for the interview. Panels include at least one external evaluator. The panel chair facilitates consensus meetings and ensures that Low-on-★ adjudications follow the protocol uniformly across sessions. ※ Must include both internal and at least one external evaluator. 1. A firefighter of the same or higher rank as the candidate. 2. A firefighter who holds a fire command qualification at the same or higher level. 3. A university professor with relevant research or teaching experience in fire science or command. | ||||

| Evaluation Criteria | Behavioral indicators are assessed based on High–Medium–Low ratings. | ||||

| Adjustable Evaluation Items | Excluding the 2 core behavioral indicators, up to 20 of other indicators may be adjusted based on real-world applicability. ※ Adjustments may include deletion, reduction, or redistribution of scores across non-core items | ||||

| Five Types of Virtual Disaster Scenario | Karaoke fire | Gosiwon fire | Construction site fire | Residential villa fire | Apartment fire |

|  |  |  |  | |

Appendix A.4. Organization and Functions of the Certification Committees

- The committee consists of the Operation Committee, Expert Committees, and the Working-level Council.

- Operation Committee: Includes the Director of 119 Operations, the Head of the Disaster Response Division, and key section chiefs from each operating institution.

- Expert Committees: Includes both the Competency Development Expert Committee and the Competency Evaluation Expert Committee.

- Working-level Council: Composed of the Disaster Response Division (lead department) and staff from operating institutions.

- Functions and Deliberation Methods of the Operation Committee

- Function: The committee decides on key matters to ensure consistency in on-site commander competency training and certification assessment, and to maintain appropriateness, fairness, objectivity, and transparency in procedures and content.

- Meeting Convening: As needed—convened by the committee chair if significant matters arise.

- Deliberation Method: A majority vote of present members determines decisions.

- Adjudication oversight: Reviews summary logs of Low-on-★ adjudications for consistency and fairness; issues corrective guidance where needed.

- Appeals handling: Defines a simple, time-bound process to review formal appeals (scope limited to procedure and scoring integrity) and records outcomes for quality assurance.

| Chairman: Director of 119 Operations -Members: Head of Disaster Response Division, Key Section Chiefs | ||

|---|---|---|

| Competency Development Expert Committee | Competency Evaluation Expert Committee | Working-level Council |

| - Chair: Head of HR Development, Central Fire School - Members: 10 internal/10 external | - Chair: Commander, Seoul Fire HQ - Members: 10 internal/10 external | - Staff from Disaster Response Division - Operational institution staff |

Appendix A.5. Simulation Scenarios and Difficulty Parameter

| (a) | |||||||

| Scenario | Dispatch Trigger | Initial Conditions | Victim Distribution | Fire Locations | Fire Spread | Challenges | Hazard Notes |

| 1. Goshiwon Fire | Fire reported on 2nd and 3rd floors | Upon arrival, one person is hanging from a 2F window requesting rescue. Deployment of an air rescue cushion is possible; use of an aerial ladder truck is not feasible. | 6 people total; 2F–1 hanging from window, 1 in hallway, 2 inside rooms 218 and 227; 3F–1 trapped on floor; Roof–1 person taking refuge. | 2 (two ignition points on 2F and 3F) | Fire extends upward from 2F to 3F | Delayed arrival due to heavy traffic congestion | City gas supply not shut off (explosion risk); one victim fell from 2F window during escape; Room 227 door locked (entry delayed); thick smoke causing near-zero visibility. |

| 2. Karaoke Room Fire | Fire outbreak on 2nd floor | Upon arrival, heavy smoke is billowing from the 2F windows. One person is visible at a 3F window calling for help. | 5 people total; 3F–1 hanging from window, 1 in corridor; 2F–1 collapsed in hallway, 2 trapped inside karaoke rooms. | 1 (ignition on 2F) | Fire spreads upward from 2F to 3F | Delayed response due to illegally parked cars | Maze-like interior layout hinders search; flammable soundproofing materials produce dense toxic smoke; insufficient emergency exits make egress difficult. |

| 3. Residential Villa Fire | Fire outbreak on 3rd floor | Upon arrival, a resident is found on a 4F balcony awaiting rescue. Fire and smoke are spreading toward the 4th floor. | 5 people total; 4F–1 on balcony; 3F–1 trapped in the burning unit, 1 in stairwell; 2F–1 semi-conscious from smoke; Roof–1 person who fled upward. | 1 (ignition in 3F unit) | Fire spreads from 3F up to 4F | None | Rapid smoke spread through open stairwell; no sprinkler system in building; small LPG gas cylinder in use (potential explosion hazard). |

| 4. Apartment Building Fire | Fire reported on 8th floor | Upon arrival, flames are venting out of an 8F apartment. A resident is spotted on a 9F balcony shouting for help. | 5 people total; 9F–1 on balcony, 1 in apartment above fire; 8F–1 in burning apartment, 1 collapsed in hallway; 7F–1 overcome by smoke on the floor below. | 1 (ignition in 8F apartment) | Fire spreads from 8F up to 9F | None | One resident jumped from 8F before rescue (fatal injuries); broken windows create backdraft risk; high-rise height complicates evacuation and firefighting operations. |

| 5.Construction Site Fire | Fire outbreak in building under construction | Upon arrival, the unfinished structure is engulfed in flames on one side. Debris and construction materials litter the scene. | 4 people total; 3 at site–1 worker on upper scaffolding, 1 trapped under debris, 1 incapacitated at ground level; 1 missing (unaccounted for amid the chaos). | 1 (ignition in scaffold/structure) | Fire spreads through scaffolding and materials on site | None | Multiple fuel and gas cylinders on site (explosion hazard); structural integrity compromised (collapse risk); lack of on-site water source slows firefighting. |

| (b) | |||||||

| VR Scenario | Real Incident (Year) | Incident Description | Scenario Validation Note | ||||

| Goshiwon Fire | Jongno District Goshiwon Fire (2018) [59] | Fire in a low-cost dormitory in Seoul; 7 killed, 11 injured. | Mirrors blocked exit and safety lapses from the real case (e.g., crucial exit obstructed, no sprinklers), trapping multiple occupants as in the actual incident. | ||||

| Karaoke Room Fire | Busan Karaoke Bar Fire (2012) [60] | Blaze in a Busan karaoke lounge; 9 people died and 25 were injured. | Scenario replicates the complex interior layout and evacuation challenges of the real event—illegal interior alterations led to hard-to-find exits (one exit hidden inside a room), lack of sprinklers, and toxic smoke in narrow corridors. | ||||

| Construction Site Fire | Icheon Logistics Warehouse Fire (2020) [61] | Massive blaze at an unfinished warehouse in Icheon; 38 construction workers killed, rapid flash fire spread. | Scenario includes flammable construction materials and explosion hazards (witnesses heard ~10 explosions in real case), reflecting the real incident’s fast spread and difficulties evacuating workers. | ||||

| Residential Villa Fire | Goyang Villa Fire (2014) [62] | Fire in a four-story “villa” house in Seoul; 1 killed, 14 injured. | Scenario reflects the open stairwell/piloti design of the actual house—the open ground-floor columns allowed fire and smoke to spread rapidly and hampered evacuation in reality, which is mirrored in the simulation. | ||||

| Apartment Fire | Uijeongbu Apartment Complex Fire (2015) [63] | Fire engulfed multiple apartment buildings in Uijeongbu; 4 killed, 124 injured. | Scenario captures high-rise fire dynamics observed in this incident—quick vertical fire spread and backdraft risks exacerbated by lack of sprinklers on mid-level floors, and a fatal fall occurred when a resident jumped to escape (a risk included in the simulation). | ||||

| (c) | |||||||

| Readiness Category | Pre-Simulation Checklist Items | ||||||

| Instructor Preparation | Instructors oriented to scenario objectives; evaluation criteria/rubric prepared; safety and emergency protocols reviewed; briefing materials ready. | ||||||

| Technical Setup | VR hardware and software tested (headsets, controllers, sensors calibrated); communication systems (radios) checked; data recording enabled; backup power and technical support available. | ||||||

| Scenario Fidelity | Virtual scenario verified against real incident data for authenticity; fire and smoke behavior tuned to realistic levels; victim placements and hazard props (e.g., gas cylinders) confirmed; trigger events (timed injects) functioning correctly. | ||||||

| Debrief Prompts | Guided debrief plan outlined (key decision points and actions noted); reflective questions prepared to prompt discussion; performance metrics and observations logged for feedback; debrief aids (video/audio recordings, score sheets) ready. | ||||||

Appendix A.6. Qualitative Coding Reliability and Exemplars

| Code Category | Definition (Brief) | N (Utterances) | Agreement (%) | Cohen’s κ | Exemplar (Anonymized) | Exemplar (EN Gloss, Optional) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unclear/Ineffective Transmission | Message lacks clarity/standard format; receiver cannot act unambiguously | 210 | 89.05 | 0.78 | “Uh… can you do that… now?” (unclear addressee / unclear action) | Missing addressee/action verb | |

| Delay/Omission of Critical Update | Late or missing transmission of time-critical information | 185 | 87.57 | 0.75 | “Delay/omission in providing fire spread and victim information updates.” | PAR; conditions–actions–needs missing | |

| Overlapping/Blocked Traffic | Simultaneous transmissions block content | 162 | 86.42 | 0.72 | “Message lost due to overlapping transmissions.” | No radio discipline/priority | |

| Ambiguous Order/Assignment | Order lacks task, location, or acknowledgment requirement | 198 | 90.40 | 0.80 | “Unit 3, proceed to location and handle task, report when complete.” | No read-back; no time marker | |

| Inter-Agency/Division Coordination Failure | Handoff, boundary, or dependency not coordinated | 154 | 84.42 | 0.67 | “Conflict in operations between divisions/agencies.” | Duplicate/contradictory tasks | |

| Missing Acknowledgment/Read-back | Receiver fails to acknowledge/read back key instruction | 176 | 88.07 | 0.76 | “No acknowledgment after task assignment.” | No closed-loop comms | |

| Missing/Invalid Progress Report | Progress markers (conditions–actions–needs) absent or invalid | 141 | 85.82 | 0.70 | “Tactical change made without a progress report.” | No time-stamped updates | |

| 1226 | 87.39 | 0.74 |

References

- Cole, D.; St Helena, C. Chaos, Complexity, and Crisis Management: A New Description of the Incident Command System; National Fire Academy: Emmitsburg, MD, USA, 2001.

- Butler, P.C.; Honey, R.C.; Cohen-Hatton, S.R. Development of a behavioural marker system for incident command in the UK fire and rescue service: THINCS. Cogn. Technol. Work 2019, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipshitz, R.; Klein, G.; Orasanu, J.; Salas, E. Taking stock of naturalistic decision making. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2001, 14, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, G.A.; Calderwood, R. Decision models: Some lessons from the field. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1991, 21, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Hatton, S.R.; Butler, P.C.; Honey, R.C. An Investigation of Operational Decision Making in Situ:Incident Command in the U.K. Fire and Rescue Service. Hum. Factors 2015, 57, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, P.C.; Bowers, A.; Smith, A.P.; Cohen-Hatton, S.R.; Honey, R.C. Decision Making Within and Outside Standard Operating Procedures: Paradoxical Use of Operational Discretion in Firefighters. Hum. Factors 2023, 65, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, K.A. The Effect of Computer-Based Simulation Training on Fire Ground Incident Commander Decision Making; The University of Texas at Dallas: Richardson, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Duczyminski, P. Sparking Excellence in Firefighting Through Simulation Training. Technology 2024. Available online: https://www.firehouse.com/technology/article/55237747/sparking-excellence-in-firefighting-through-simulation-training (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Lewis, W. Commander Competency. 2023. Available online: https://www.firehouse.com/technology/incident-command/article/21288477/the-making-of-the-most-competent-fireground-incident-commanders (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Radianti, J.; Majchrzak, T.A.; Fromm, J.; Wohlgenannt, I. A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: Design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda. Comput. Educ. 2020, 147, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, C. Addressing Gaps in Command Capability and Experience in the Copley Fire Departme; National Fire Academy: Emmitsburg, MD, USA, 2018.

- Lee, E.P. Analysis of causes of casualties in Jecheon sports center fire-Focus on structural factors of building and equipment. Fire Sci. Eng. 2018, 32, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia Contributors. Jecheon Building Fire. 2025. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jecheon_building_fire#:~:text=people%20and%20injuring%20another%2036.,2 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Wikipedia Contributors. Miryang Hospital Fire. 2025. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miryang_hospital_fire (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Much Work Remains to Improve Communications Interoperability; F. responders; U.S. Government Accountability Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

- Endsley, M.R. Theoretical underpinnings of situation awareness: A critical review. Situat. Aware. Anal. Meas. 2000, 1, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Hatton, S.R.; Honey, R.C. Goal-oriented training affects decision-making processes in virtual and simulated fire and rescue environments. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2015, 21, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reader, T.; Flin, R.; Lauche, K.; Cuthbertson, B.H. Non-technical skills in the intensive care unit. Br. J. Anaesth. 2006, 96, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, P.; Bearman, C.; Butler, P.; Owen, C. Non-technical skills for emergency incident management teams: A literature review. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2021, 29, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijkmark, C.H.; Metallinou, M.M.; Heldal, I. Remote Virtual Simulation for Incident Commanders—Cognitive Aspects. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigley, G.A.; Roberts, K.H. The incident command system: High-reliability organizing for complex and volatile task environments. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1281–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.A.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Overcoming dysfunctional momentum: Organizational safety as a social achievement. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 1327–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.; Sutcliffe, K. Managing the Unexpected Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.A.; Lee, J.E.; Ban, Y.U.; Lee, H.-J.; You, S.; Yoo, H.J. Safety Measure for Overcoming Fire Vulnerability of Multiuse Facilities—A Comparative Analysis of Disastrous Conflagrations between Miryang and Jecheon. Crisis Emerg. Manag. Theory Prax. 2018, 14, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchek, S. Organizational resilience: A capability-based conceptualization. Bus. Res. 2020, 13, 215–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.H.; Nam, J.H.; Shin, S.A.; Lee, J.B. A Study on the Preliminary Validity Analysis of Korean Firefighter Job-Related Physical Fitness Test. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Chuang, Y.J. The Study of Alternative Fire Commanders’ Training Program during the COVID-19 Pandemic Situation in New Taipei City, Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Fire Agency. Strengthening Fire-Ground Command Capabilities: First Implementation of “Strategic On-Scene Commander” Certification. In Disaster Incident News; 2024. Available online: https://www.nfa.go.kr/nfa/news/disasterNews/?boardId=bbs_0000000000001896&mode=view&cntId=208261 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- National Fire Chiefs Council. National Operational Guidance. 2023. Available online: https://nfcc.org.uk/our-services/national-operational-guidance/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Jane Lamb, K.; Davies, J.; Bowley, R.; Williams, J.-P. Incident command training: The introspect model. Int. J. Emerg. Serv. 2014, 3, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, M.B.D.K.; Verhoef, I. Why Simulation is Key for Maintaining Fire Incident Preparedness. 2015. Available online: https://www.sfpe.org/publications/fpemagazine/fpearchives/2015q2/fpe2015q24 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Thielsch, M.T.; Hadzihalilovic, D. Correction to: Evaluation of Fire Service Command Unit Trainings. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2021, 12, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, S. A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorate of Education; G.C. University: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2013; p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- Carolino, J.; Rouco, C. Proficiency Level of Leadership Competences on the Initial Training Course for Firefighters—A Case Study of Lisbon Fire Service. Fire 2022, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancko, D.; Majlingova, A.; Kačíková, D. Integrating Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, Mixed Reality, Extended Reality, and Simulation-Based Systems into Fire and Rescue Service Training: Current Practices and Future Directions. Fire 2025, 8, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthiaume, M.; Kinateder, M.; Emond, B.; Cooper, N.; Obeegadoo, I.; Lapointe, J.-F. Evaluation of a virtual reality training tool for firefighters responding to transportation incidents with dangerous goods. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 14929–14967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, I. Training’s New Dimension, with Fire Service College AI-Powered, Firefighter Training 2025. Available online: https://internationalfireandsafetyjournal.com/trainings-new-dimension-with-fire-service-college/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Rizzo, A.; Morie, J.F.; Williams, J.; Pair, J.; Buckwalter, J.G. Human Emotional State and its Relevance for Military VR Training. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 22–27 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lele, A. Virtual reality and its military utility. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2011, 4, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallavicini, F.; Argenton, L.; Toniazzi, N.; Aceti, L.; Mantovani, F. Virtual Reality Applications for Stress Management Training in the Military. Aerosp. Med. Hum. Perform. 2016, 87, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UK Research and Innovation. Improving Command Skills for Fire and Rescue Service Incident Response. Available online: https://www.ukri.org/who-we-are/how-we-are-doing/research-outcomes-and-impact/esrc/improving-command-skills-for-fire-and-rescue-service-incident-response/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Alhassan, A.I. Analyzing the application of mixed method methodology in medical education: A qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, B. “Good Enough” Isn’t Enough: Challenging the Standard in Fire Service Training. 2025. Available online: https://www.fireengineering.com/firefighting/good-enough-isnt-enough-challenging-the-standard-in-fire-service-training/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Park, J.-C.; Suh, J.-H.; Chae, J.-M. Simulation-Based Evaluation of Incident Commander (IC) Competencies: A Multivariate Analysis of Certification Outcomes in South Korea. Fire 2025, 8, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapsford, O. From the Fire Ground: Insights into Crisis Command Decision-Making. In Coventry University Research Presentation; Coventry University: Coventry, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hartin, E. Ventilation Strategies: International Best Practice; CFBT-US: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Menomonee Falls Fire Department, T.B. Driver Operator Manual; Menomonee Falls Fire Department, T.B.: Menomonee Falls, WI, USA, 2008; pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson Township Volunteer Fire Company. Rapid Intervention Team Operations: Standard Operating Guidelines; National Fire Academy: Jefferson Township, PA, USA, 2000; p. 3.

- Hansen, S. Rapid Intervention Team Operations: Standard Operating Procedures; U.S. Fire Administration, Federal Emergency Management Agency: Emmitsburg, MD, USA, 2000; p. 70.

- Sowby, R.B.; Porter, B.W. Water Supply and Firefighting: Early Lessons from the 2023 Maui Fires. Water 2024, 16, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ścieranka, G. Krytyczna ocena wymagań przeciwpożarowych dotyczących sieci wodociągowych/Firefighting Water-supply System Requirements—A Critical Assessment. Bezpieczeństwo I Tech. Pożarnicza 2017, 48, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Emergency Management Agency U.S Fire Administration. ICS Organizational Structure and Elements; Federal Emergency Management Agency: Emmitsburg, MD, USA, 2018; p. 11.

- International Association of Fire Fighters. Incident Command Module; International Association of Fire Fighters: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Preventing Deaths and Injuries to Fire Fighters by Establishing Collapse Zones at Structure Fires; National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2014; p. 6.

- HM Government Department for Communities and Local Government. Fire and Rescue Manual: Volume 2—Fire Service Operations, Incident Command, 3rd ed.; The Stationery Office (TSO): London, UK, 2008.

- Moynihan, D.P. From Forest Fires to Hurricane Katrina: Case Studies of Incident Command Systems. In Networks and Partnerships Series; IBM Center for The Business of Governmen: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Toolshero. Recognition-Primed Decision Making (RPD); Toolshero: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, G. Naturalistic decision making. Human factors. J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2008, 50, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea JoongAng Daily. No sprinklers in gosiwon where fire killed 7 day laborers. Korea JoongAng Daily, 11 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- LIVEJOURNAL. Korean Police Find Illegal Changes in Karaoke Fire Venue. 2012. Available online: https://omonatheydidnt.livejournal.com/9144474.html (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- The Guardian. South Korea fire kills nearly 40 construction workers. The Guardian, 30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhua News Agency. South Korea wildfires force thousands to evacuate, Yonhap reports. Xinhua, 13 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Korea JoongAng Daily. Fire at apartment blocks kills 4, leaves 124 injured. Korea JoongAng Daily, 11 January 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Competency Domain | Sub-Competency (Code & Description) | Unsuccessful Sub-Competency (Count) | Average Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2. Response Activities | 2-4. Crisis Response & Progress Management | 39 | 74.20 |

| 3. Firefighting Tactics | 3-4. Ventilation | 39 | 75.60 |

| 2. Response Activities | 2-1. Apparatus Placement | 39 | 76.40 |

| 2. Response Activities | 2-2. Standard Response Tactics | 38 | 78.20 |

| 3. Firefighting Tactics | 3-1. Firefighting Water Supply | 32 | 78.20 |

| 1. Situation Assessment | 1-4. Victim Information Gathering & Dissemination | 32 | 78.20 |

| 2. Response Activities | 2-5. Identification & Management of Fireground Elements | 33 | 78.90 |

| 2. Response Activities | 2-6. Unit Leader Task Execution | 36 | 79.90 |

| 5. Achievement of Core Objective | 5-1. Adequacy of Achieving Rescue Objectives ★ | 26 | 80.70 |

| 3. Firefighting Tactics | 3-3. Hose Deployment, Water Application & Nozzle Placement | 22 | 82.20 |

| 1. Situation Assessment | 1-5. Requesting Additional Firefighting Resources | 30 | 82.30 |

| 4. Communication | 4-2: Information Delivery Effectiveness | 27 | 82.30 |

| 5. Achievement of Core Objective | 5-2. Crew Safety Management | 25 | 82.30 |

| 2. Response Activities | 2-3 Assigning Tasks to Later Arriving Units | 31 | 83.70 |

| 4. Communication | 4-1. Radio Communication Principles | 22 | 84.10 |

| 1. Situation Assessment | 1-3. Initial Situation Report & Command Declaration ★ | 25 | 84.20 |

| 4. Communication | 4-3. Situation Handover to Arriving Chief Officer | 19 | 86.70 |

| 3. Firefighting Tactics | 3-2. Forcible Entry & Interior Attack Initiation | 10 | 88.70 |

| 1. Situation Assessment | 1-2. Situation Dissemination en Route | 12 | 92.40 |

| 1. Situation Assessment | 1-1. Information Gathering & Mission Sharing en Route | 5 | 93.10 |

| Competency Domain | Sub-Competency (Code & Description) | Unsuccessful Sub-Competency (Count) | Average Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2. Response Activities | 2-4. Crisis Response & Progress Management | 39 | 74.20 |

| 3. Firefighting Tactics | 3-4. Ventilation | 39 | 75.60 |

| 2. Response Activities | 2-1. Apparatus Placement | 39 | 76.40 |

| 2. Response Activities | 2-2. Standard Response Tactics | 38 | 78.20 |

| 3. Firefighting Tactics | 3-1. Firefighting Water Supply | 32 | 78.20 |

| 1. Situation Assessment | 1-4. Victim Information Gathering & Dissemination | 32 | 78.20 |

| 2. Response Activities | 2-5. Identification & Management of Fireground Elements | 33 | 78.90 |

| 2. Response Activities | 2-6. Unit Leader Task Execution | 36 | 79.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, J.-c.; Yun, J.-c. Analysis for Evaluating Initial Incident Commander (IIC) Competencies on Fireground on VR Simulation Quantitative–Qualitative Evidence from South Korea. Fire 2025, 8, 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8100390

Park J-c, Yun J-c. Analysis for Evaluating Initial Incident Commander (IIC) Competencies on Fireground on VR Simulation Quantitative–Qualitative Evidence from South Korea. Fire. 2025; 8(10):390. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8100390

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Jin-chan, and Jong-chan Yun. 2025. "Analysis for Evaluating Initial Incident Commander (IIC) Competencies on Fireground on VR Simulation Quantitative–Qualitative Evidence from South Korea" Fire 8, no. 10: 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8100390

APA StylePark, J.-c., & Yun, J.-c. (2025). Analysis for Evaluating Initial Incident Commander (IIC) Competencies on Fireground on VR Simulation Quantitative–Qualitative Evidence from South Korea. Fire, 8(10), 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8100390