Abstract

This paper aims to provide a better understanding of the transition towards a new paradigm of wildfire risk management in Victoria that incorporates Aboriginal fire knowledge. We show the suitability of cultural burning in the transformed landscapes, and the challenges associated with its reintroduction for land management and bushfire risk reduction after the traumatic disruption of invasion and colonization. Methods of Environmental History and Regional Geography were combined with Traditional Ecological Knowledge to unravel the connections between past, present and future fire and land management practices. Our study area consists of Dja Dja Wurrung and Bangarang/Yorta Yorta Country in north-central Victoria. The results show (i) the ongoing socio-political process for building a renewed integrated fire and land management approach including cultural burning, and (ii) the opportunities of Aboriginal fire culture for restoring landscape resilience to wildfires. We conclude that both wildfire risk management and cultural burning need to change together to adapt to the new environmental context and collaborate for mutual and common benefit.

1. Introduction

After the 2019–2020 Black Summer bushfires which burned 1,505,004 hectares and resulted in five lives lost in Victoria [1,2,3], there has been a call for a paradigm change in wildfire risk management. Conventionally, wildfire risk management has focused on fire suppression and reactive firefighting for assets and people protection [4]. However, the changing fire regime indicates the need for a more expansive approach that incorporates Aboriginal fire knowledge [5,6,7]. In the aftermath of the Australian megafires, Steffensen published ‘Fire Country’, a popularized book claiming the need for a revival of cultural burning practices [8]. The Indigenous led network, Firesticks Alliance, has played a key role in centering the political and scientific debate around the potential contribution of cultural burning to wildfire risk mitigation [9].

The term ‘cultural burning’ refers to burning practices developed by Aboriginal people to enhance the health of the land and its people. According to The Victorian Traditional Owner Cultural Fire Strategy, “cultural burning is right fire, right time, right way and for the right (cultural) reasons according to lore” [10]. Therefore, cultural burning is an ancestral and living practice of land management with a spiritual, holistic nature and place-based approach.

While Aboriginal organizations and media releases are advocating for cultural burning to be incorporated within land management practices, several scientific studies have focused on the severity of the 2019–2020 bushfires to highlight the factors creating the conditions for these megafires. These are climate change, ecosystem degradation and landscape planning and management [11,12,13]. Black Saturday, 7 February 2009 had an even more important impact in Victoria than the Black Summer bushfires, as it caused the death of 173 people [14]. There is no doubt that Australian society is facing a new fire regime in the context of climate change and transformed landscapes [15,16].

Wildfires occur and have an intrinsic relationship with the landscape, both landscape and fire regimes have historically evolved together [17,18]. Australia has been a fire adapted continent for millennia [8,15,19]. Fire is a key cultural tool for the landscape management of Aboriginal communities [8,9,10,20]. On the other hand, wildfire risk has steadily grown since the late 19th Century. It is well documented now that human-driven landscape change triggered by European colonization and exacerbated by climate change has destabilized the Australian social-ecological system leading to new fire regimes, frequently characterized by catastrophic megafires [5,15,19].

The increasing concern with wildfire risk and strategies for mitigation in Australia, particularly in Victoria, has resulted in extensive scientific literature over the past two decades [1,2,3,12,13,14,15,16,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Recent research has tended to show the importance and significance of cultural burning and the challenges associated with its reintroduction for land management and bushfire risk reduction [4,5,6,7,8,11,26,27]. The Australian 2021 State of the Environment Report also aligns with scientific studies to recognize that cultural burning reduces the risk of bushfires [28,29]. However, the fact that Aboriginal fire culture was excluded for two centuries has created social, cultural and economic barriers to understanding how and what the social-ecological connections for fire management might comprise. Moreover, invasion and colonization brought about not only a radical landscape change and severe ecological damage but also a traumatic disruption and disconnection of people from land and fire [30]. Hence, the reconnection and social reconstruction for restoring cultural burning is a critical process that needs time and opportunities to overcome the multiple institutional, political and social barriers [31,32].

The Victorian Traditional Owner Cultural Fire Strategy and follow-up policy documents state that cultural fire has a huge potential for healing people and healing Country, meaning the ancestral territory which includes all of the sentient and non-sentient parts of the world and the interactions between them, according to Aboriginal lore [10,33]. According to Neale, “Country is central to everything Aboriginal: it is a continuum, without beginning or ending. In this worldview, everything is living—people, animals, plants, rocks, earth, water, stars, air and all else. There is no division between animate and inanimate” [34] (p. 1). Science and empirical evidence have likewise demonstrated that cultural burning can recreate landscape mosaics, enhance biodiversity, and reduce bushfire risk [29,35,36,37]. This entails Aboriginal people coming back to their Country to adapt to it, reconnecting with each other, reading the current landscapes and relearning cultural burning practices together in the transformed environment. It is a long journey of dialogue and trust building for a long-term effective collaboration between Aboriginal communities and government agencies [8,37].

Our study introduces a novel methodology for combining empirical evidence and an epistemological approach to clarify the suitability of cultural burning practices in the context of transformed landscapes and climate change. We have focused the research on the case-study of Dja Dja Wurrung and Bangarang/Yorta Yorta Countries in north-central Victoria [38,39,40]. Our primary aim is to unravel how this transition incorporating cultural burning can be mobilized and integrated into the wider landscape and fire risk management approaches. We combine Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) with scientific methods of Environmental History and Regional Geography, to answer the following research questions: How can cultural burning contribute to wildfire risk management in the contemporary environment? What are the key-issues for a transition towards a new paradigm that incorporates Aboriginal fire knowledge within transformed landscape management? We hypothesize that both wildfire risk management and cultural burning need to change together to adapt to the new environmental context and collaborate for mutual and common benefit.

This is one of the first papers to integrate the challenges that are currently facing both Victorian fire government agencies and Aboriginal communities, looking from different angles to converge at some critical points. Previous research on Aboriginal fire has largely overlooked the role of fire in pre-colonization landscapes [41], only a few studies have investigated the recent connection of cultural burning with bushfire management [6,7,26,27,30,37,38]. According to Christianson, “few social science research projects worked with Indigenous communities to examine contemporary wildfire management” [42]. We are addressing the need to connect the past to the present and future to face the social-environmental challenges of bushfire risk in Australia [43]. The findings of this research will provide (i) a realistic assessment of the opportunities for cultural burning practices to adapt to the new environmental context, and (ii) a better understanding of how the concept of wildfire risk management is changing with the call for cultural burning to be accepted and adopted by the fire agencies and more widely by stakeholders and land managers.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper is derived from cultural burning experiences, field observations, notes and photography; scholarly literature, research reports, documentary study of policy instruments relating to fire and land management; a collection of archival documentary sources; and semi-structured interviews with agency managers associated with bushfire risk in Victoria. Methods of Environmental History and Regional Geography were applied to unravel the connections between past, present and future fire and land management practices. We used socio-spatial analysis—including landscape observations over the period of the research, and a critical review of scholarly literature, research reports, policy instruments, and archival documentary sources—to understand the ongoing interaction between traditional practices and historical processes with landscape dynamics and fire behavior [18].

This research, including the selection of case study sites, draws on the lived experiences of the first author––an Aboriginal researcher and cultural practitioner––who brings situated knowledge and personal relationships to people, land, and fire in the case study territories. Amos Atkinson is a proud Way Wurru, Bangarang, Dja Dja Wurrung, Barrapa Barrapa, Wemba Wemba, Daug Wurrung, Ngura-illam Wurru Wiradjuri Man. He is a cultural fire practitioner and member of the Firestick Alliance. The second author, Cristina Montiel, undertook this research study within the framework of a long-term research program on fire policies, fire history and social aspects of fire management, funded through several Spanish national grants. The research paper was developed as an interdisciplinary collaboration between the two authors and draws on the first author’s existing relationships and knowledge of ongoing projects across the case study.

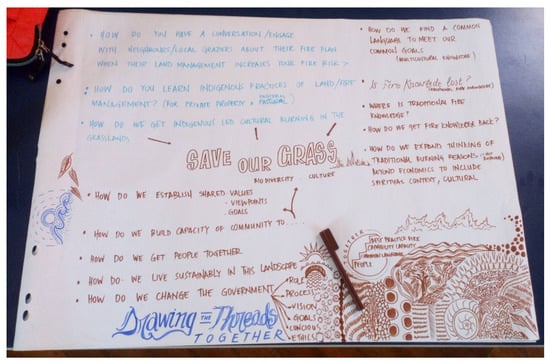

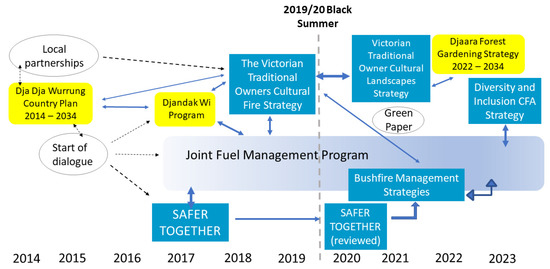

A targeted literature review on Aboriginal fire culture and fire regime in transformed landscapes of Victoria was undertaken to explore the challenges of bushfire risk management and the aspirations of Aboriginal communities. Cristina Montiel reviewed key agency documentation and technical reports about cultural burning and bushfire risk management. She conducted sixteen in-person semi-structured interviews with key experts, including fire managers and technicians, academics, and a State-wide cultural heritage advisor. The research interviews were conducted during her research stays in October–December 2018, March 2020 and March–May 2023. The interviewees came from the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA)—the former Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), the Country Fire Authority (CFA), Parks Victoria, Local Councils, The University of Melbourne, and La Trobe University. The interviews were not audio recorded, nor were they transcribed. During the interviews, the second author took notes of the responses to the questions and emerging themes. The semi-structured interviews were not addressing cultural fire practitioners, thus ethical protocols were not requested as part of the study design. The main themes and questions discussed in the interviews were related to the challenges of new fire regimes, the socio-spatial context for wildfire risk management, and the ongoing policy process to enable Traditional Owners (TOs) to care for the Country. In addition, between 2018 and 2023, the authors participated in a total of six workshops at the national, regional, and local levels, to understand the perspectives of diverse stakeholders engaged in bushfire risk management and cultural fire practices. This informed our approach to investigate the current challenges and opportunities for cultural burning practitioners to work together with government fire and land management agencies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Notes of the workshop “Talking Fire: Reviving Indigenous burning in a changed landscape”, Newstead, 30 November 2018.

Traditional knowledge of fire is mainly practical based on the experience and memory of the Indigenous communities. This creates a limitation for systematic research, along with the place-based nature of cultural burning practices that advises a local approach and does not allow for generalizations. As a cultural fire knowledge holder and a member of the Firestick Alliance, Amos Atkinson conducted cultural burns at three significant Aboriginal heritage sites in Dja Dja Wurrung and Bangarang/Yorta Yorta Countries. These cultural burn practices were observed and analyzed through the fieldwork carried out from October 2018 to May 2023 to assess their effects on the landscape structure. Then, the Aboriginal fire knowledge, documentary sources and empirical data were integrated through a systemic qualitative analysis to answer the research questions. The method used to code interviews and key findings was first, a critical analysis of the interviewees replies, primary data sources and empirical evidence to identify the main components of the socio-spatial system. This was followed by a qualitative analysis of the socio-spatial components to clarify the system’s structure and relational dynamics. We have highlighted the place-based and multiscale (site, locality, landscape, region) approach for an accurate assessment of land-fire-people connections.

2.1. Case Study

Our study area consists of Dja Dja Wurrung and Bangarang/Yorta Yorta Country in north-central Victoria [44]. This area is part of the Central Murray-Goulbourn region, a resource and culturally rich territory that experienced the environmental impact of mining during the gold rush in the second half of the 19th century [45]. Agriculture, pastoralism and the timber industry have also had significant effects on the Country. The Barmah region supported an extensive timber industry from the late nineteenth—mid twentieth century. The forest there has been completely logged. Furthermore, an extensive network of transport and irrigation infrastructure has been developed to meet colonial economic ambitions [46]. Most of this inland surface is unburnt since at least 1995 and was outside the spatial extent of the 2019–2020 mega fires [3]. However, the impact of other disturbances such as floods and drought highlights the disastrous consequences of the radical landscape transformation since the British invasion [47]. Worse, European settlement meant dispossession, slaughtering, forced removal of Aboriginal people, and occupation of their sacred sites, causing disconnection of people from their Country.

The destructive colonial actions radically changed the landscape character and functions of the Central Murray-Goulburn region since the 1830s [48]. Squatters—the first white settlers who occupied vast pastoral leases—over-cleared the trees and began to illegally occupy the area for grazing cattle and sheep before regulation by state and colonial governments. These are the so-called pastoral runs in Australia and New Zealand [49,50]. In the 1860s, the Land Acts modified the large land holdings of the squatters to allow new settlers to create a livestock and cropping landscape by fencing and regulating the river system [51,52]. Therefore, the millennia-evolved complex mosaic of floodplain forest, open woodlands, scrub, heathland, grassland and sedgeland which Aboriginal people had managed, was replaced by simplified, homogenous and even fragmented landscapes of large croplands, sheep and dairy farms [48].

The Central Murray-Goulburn region is regarded as part of Australia’s Food Bowl because of the development of a high-value irrigated agriculture system since the late 19th century. The expansion of this large-scale irrigation scheme involved the construction of a vast network of channels, dams and reservoirs [46]. At the time, the irrigated agriculture system followed a profound process of transformation during the second half of the twentieth century due to the salinity problems caused in part by over-irrigation [52]. The advent of the ‘green revolution’, with fertilizers and new pasture crops (lucerne, clovers) introduced into the landscape, contributed to the agricultural restructuring. There was likewise a trend of aggregation of smaller farms into larger ones, due to increasing production costs. In addition to this, from the early 2000s, the irrigation system has undergone an extensive restructuring due to the Millennium Drought. This accumulated cascade of profound landscape changes over two centuries has resulted in soil degradation, introduction of invasive species, reduction of biodiversity, decline of tree health, and loss of indigenous wildlife. Contemporary Aboriginal people argue that their Country is sick [53].

Dja Dja Wurrung Country extends from north of the Great Dividing Range near the towns of Creswick and Daylesford to Boort in the north, Donald in the northwest and Rochester in the northeast. This territory includes the City of Greater Bendigo and the main goldfields in Victoria. It also encompasses part or all of the catchments of the Richardson, Avon, Avoca, Loddon and Campaspe Rivers. In all, it represents 17,369 km2 (7.32% of Victoria) where Dja Dja Wurrung People—trading as Djaara—are recognized as the Traditional Owner group. In 2013, the Victorian Government and the Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation entered into a Recognition and Settlement Agreement that legally recognizes the external boundaries of the Country, named Djandak [54].

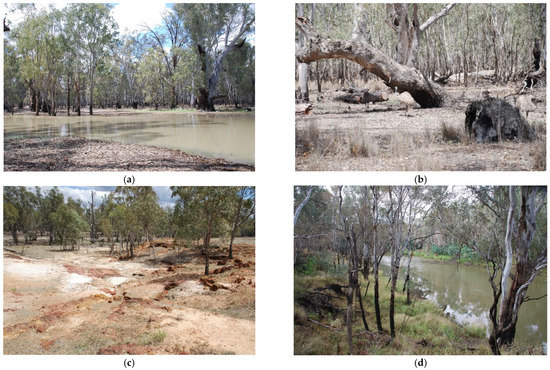

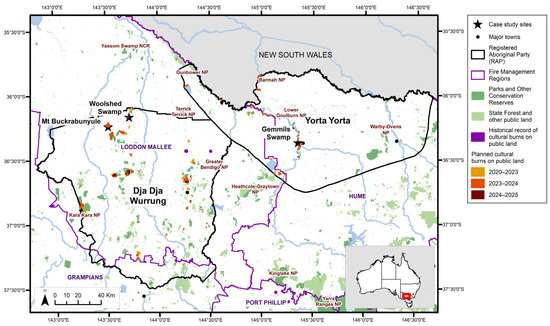

Yorta Yorta means ‘no no people’, and Bangarang means ‘tall tree people’. In Bangarang/Yorta Yorta Country, Murray river and its tributaries, namely the Goulburn (‘Kialla’, meaning ‘Godfather River’), are called ‘Dhungalla, the Big River’ [55]. Bangarang/Yorta Yorta Country extends through a territory of 200,000 km2 over Victoria and New South Wales [56] and includes key sites of cultural and spiritual significance (Figure 2), for example, the Flats, located on the floodplains of the Goulburn River, between Mooroopna deep waterfall and Shepparton. The Barmah-Millewa Forest, now recognized as an iconic river red gum complex ecosystem is upstream from the confluence of the Goulburn River with the Murray River and covers approximately 66,000 ha of floodplain over Victoria and New South Wales and is referred to as the heartland of the Bangarang/Yorta Yorta people [49,56,57,58].

Figure 2.

Sites of cultural and spiritual significance in Dja Dja Wurrung and Bangarang/Yorta Yorta Country: (a) Barmah Forest; (b) Undera woodland; (c) Bendigo; (d) Goulburn River in The Flats, Mooropna.

Yorta Yorta Country covers the areas of Greater Shepparton, Moira and Benalla. In 2007, the Yorta Yorta nation gained Registered Aboriginal Party (RAP) status that recognizes an area of 13,199 km2 (5.56% of Victoria). However, the Native Title claim, being a long and hard judicial process of struggle for land justice and recognition of Yorta Yorta ancestral connections to the Country, has not yet succeeded in breaking down the remaining barriers with government agencies for effective water and land management based on traditional law and practice [59,60,61,62].

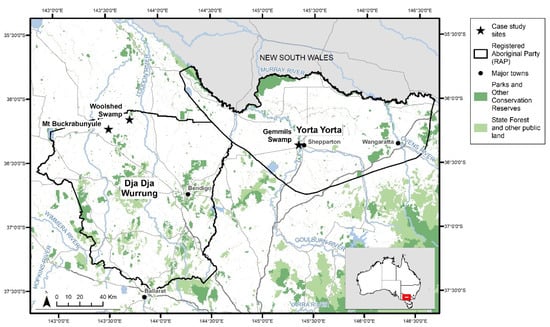

The site selection for this study was based on the landscape diversity of north-central Victoria associated with the following criteria: (1) vegetation type; (2) main purpose of the cultural burn; (3) partnership of Aboriginal communities with government agencies for land management. We selected three sites of high heritage value where cultural burning practices have been reintroduced and are representative of the different land management purposes and procedures of reconnection with the Country.

The first site is Mount Buckrabunyule, a granite outcrop of cultural significance for the Dja Dja Wurrung People. Bush Heritage Australia (an NGO) acquired this place in 2021 for protection and ecological restoration purposes through a joint management plan with Djaara. Gemmill Swamp is the second selected site. This is a sacred site of the Bangarang/Yorta Yorta people. It is a Goulburn River floodplain forest and semi-permanent freshwater wetland between the urban centers of Mooroopna and Shepparton, where cultural burning practices are being developed in partnership with the Aboriginal community and Yorta Yorta Parks rangers. The third selected site is Woolshed Swamp, located south of Boort, which consists of a Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) woodland with a black box (Eucalyptus largiflorens) on the higher areas. This is a high value wetland for its large size (497 ha) [63]. Despite its declaration as a Wildlife Reserve, it is a degraded ecosystem as a result of colonial land management. The Victorian Auditor-General’s Office (VAGO) has also used a cultural burn performed by the Dja Dja Wurrung and Barapa Barapa Traditional Owner groups at Woolshed Swamp as a case study of its independent assurance report to Parliament after the 2019–2020 Victorian bushfires [64]. Our case study locations and site distribution are represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Map of the case study and location of selected sites.

2.2. Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

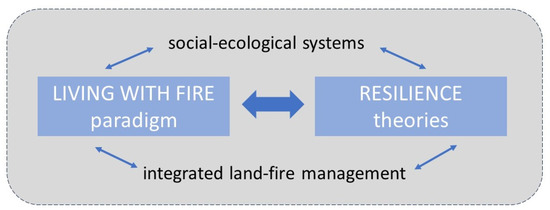

The theoretical framework of our research is the ‘living with fire’ paradigm and resilience theories [65,66]. We pay particular attention to the epistemological aspects and empirical evidence of Aboriginal cultural burning practices regarding wildfire risk mitigation over the long-term. In this regard, the theory of change defined by Wunder et al. (2021) is applied to highlight how difficult it is to measure objectively in the present the expected long-term goals of wildfire risk reduction strategies [67].

The ‘living with fire’ paradigm is a holistic and systemic approach to integrated land-fire management. The vision is to rescale what currently tends to be national questions looking for universal solutions, to local practices centered on coexisting with fire [68,69]. Coexistence with fire requires learning to read landscape at the local scale and acquiring a deep understanding of social-ecological systems [7,70]. Living with fire doesn’t mean accepting catastrophic wildfires but returning the right fire to the landscape to reduce vulnerability, in particular in the iconic fire-sensitive places [71].

In opposition to Western spatial planning and cultures, First Nation’s Traditional Ecological Knowledge is critical to reconnecting and adapting fire to each environmental context [72,73]. While there are many ways to understand Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), for the purpose of this research, we approached TEK in terms of an evolving understanding of place-based cultural values and competencies that can reveal critical connections to care for the Country [74]. Furthermore, the return of cultural fire practices to the Country is intended to restore the native biological diversity and the altered ecological processes which are one of the structural causes and major consequences of new fire regimes [68,73,75]. The landscape-scale and site-specific approach to land-use planning and fire policies also offers new opportunities for a shift from reactive firefighting action plans to proactive strategies of bushfire risk management.

Resilience theories are suitable to answer our research questions as resilience is related to disturbance, change and adaptation. Walker and Salt have defined resilience as “the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize so as to retain essentially the same function, structure, and feedback—to have the same identity” [76] (p. 3). Thus, identity is a key element of resilience. This is particularly noteworthy regarding Aboriginal communities. Their coevolution with the Country for more than 60,000 years by maintaining and enhancing their cultural heritage to cope with disturbances and adversities has been acknowledged as outstanding [77]. Resilience is based on complex science theory and as such, emphasizes cycles of adaptation, change and renewal. A shift in wildfire risk management can be understood in terms of the adaptive cycle [78]. In this context, First Nations’ epistemologies and practices of cultural fire can play a key role toward the ‘living with fire’ paradigm [79] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Diagram of the conceptual and theoretical framework.

Aboriginal understanding of resilience particularly highlights the importance of socio-cultural and spiritual connections to Country. Following Williamson, Weir and Cavanagh “Aboriginal peoples’ cultural identity comes from the land”. Hence, the immense grief of devastating bushfires related to the colonial legacy, superimposed on the trauma of dispossession and forced removal from Country, is incomprehensible [80].

3. Results

3.1. Bases of Cultural Burning in the Contemporary Environment

Culture is a socio-spatial construction through history that confirms collective identity and community solidarity [34]. The main components of culture are society, place and time. Thus, culture is not static, but dynamic and adaptive, in permanent change throughout linear and non-linear processes [17]. In the case of First Nations, culture or Law refers to a millennia-long process of a deep spiritual nature that is constantly evolving [81] (p. 37).

Aboriginal fire culture connects to the Country and its long collective heritage. The Country involves eco-cultural concepts of belonging, stewardship and health. It embodies ancestors, spirits and Dreaming that comprise a place [82,83,84]. Following Griffiths, the Dreaming describes a varied, contoured and continually transforming tradition [85]. The dreaming stories are linked to sacred sites and the Earth’s formation, as well as to the environments where Indigenous people practice ceremonies and feel a stronger connection with ancestry (pp. 39–40). This intimate connection is a source of Aboriginal people’s identity as communities with a millennia-long history [8,20,51]. Thus, the Country is intrinsically linked to traditional laws, culture and identity. The totemic relationships of Aboriginal people with the Country assures their further connection of physical presence. This is the strong basis of the TOs land and water rights claims after the historic dispossession of the Country that occurred as a result of colonization.

The Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA) is the first major legal mechanism for recognizing the existing rights of Aboriginal people to their territories. However, it is also one of the weakest legal Land Acts in Australia, as it has been ineffective in getting Aboriginal communities back in the Country. Thus, the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 (Vic) (TOs Act) was introduced in Victoria as an alternative to the lengthy and uncertain processes of the native title regime. It provides recognition of various rights of TOs, funding, and use, access and management of natural resources [86]. However, the terms of this fast legal path seem unreasonable, in entering into this Recognition and Settlement Agreement, the Aboriginal communities are not able to make another Native Title claim for the next 1000 generations.

The Dja Dja Wurrung Recognition and Settlement Agreement was the second comprehensive settlement under the TOs Act in March 2013. The first native title claim in Victoria was made on behalf of the Bangarang/Yorta Yorta people in 1994. In December 1998, the claim was dismissed in the Federal Court. The Bangarang/Yorta Yorta people appealed to the High Court, but the decision of the Federal Court was upheld on 12 December 2002 by a majority of five to two [54,61]. Further to this judgment, the legal framework changed to make it easier for people to apply for Native Title as it was considered that the decision on Bangarang/Yorta Yorta Native Title was unfair and unjust for Aboriginal communities. Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation had also lodged four native title claims in the Federal Court between 1998 and 2000, although the TOs Act settlement finalized all these native title claims [87]. The Victorian Government entered into a Cooperative Management Agreement with the Yorta Yorta Nation in June 2004, and TOs Land Management Agreement in October 2010.

This complex cultural and legal context is a fundamental premise for cultural burning, as fire is part of the Country and a sacred tool that has many Dreaming stories attached to it from all around Australia [34]. Cultural burning, sometimes referred to as traditional burning, is the TEK of Australia’s First Peoples. Cultural burning is much more than bushfire hazard reduction, fire stick farming or a land management tool [88]. Cultural burning or traditional burning has not just one specific practical goal, but a holistic, comprehensive and spiritual significance. Fire is one of the connecting links of Aboriginal people with the Country. Western science has tried to identify the different reasons or purposes for cultural burning practices, such as hunting, enhancing native flora and fauna, controlling invasive plants, recovering indigenous food plants, or bushfire risk mitigation, among others. However, cultural burning practices are holistic, totemic and multipurpose. TOs emphasize that cultural fire is applied to achieve culturally meaningful objectives, though risk reduction is often a complementary outcome [89].

The overall aim of ‘Djandak Wi’ (Country fire) is caring for the Country and people [90]. Furthermore, Aboriginal fire is not uniform, but a place-based culture. There is not a single Aboriginal fire culture. There are as many fire cultures as there are Aboriginal Countries in Australia [43], because fire culture is as complex and diverse as the landscapes are. In general terms, cultural burning is socio-ecological system-based rather than property-system centric. Hence, we refer to cultural burning and cultural landscapes. Both realities are inseparably connected. Fire knowledge is held by groups of people within a specific landscape [91]. People must be on the ground, connected to the Country, to read the landscape and manage the right fire at the right time [8].

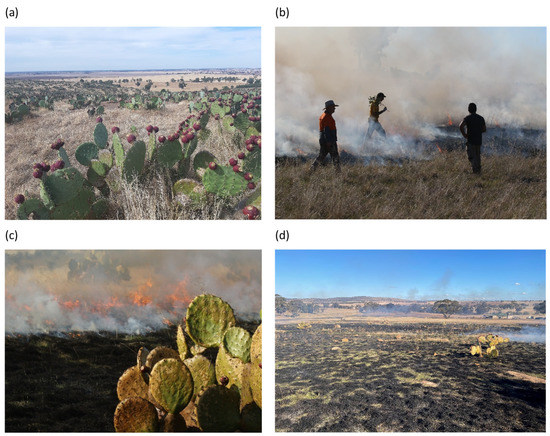

To start a fire, Aboriginal people traditionally use fire sticks such as a tea tree bark torch, or some eucalyptus branches. Cultural burning techniques consist of conducting a low intensity mosaic burn of self-extinguishing fires in small plots, and sometimes using the waterways or the animals’ tracks as anchor lines. The right fire is slow, gentle, cool and low intensity [8] (Figure 5). Cultural burning is a patch burn at the landscape scale, through a journey that brings ecological restoration, well-being, productive benefits and bushfire risk reduction. According to the statement of a Ngadju Elder in the part of south-western Australia known as the Great Western Woodlands, “the reason why there’s so many [woodland] wildfires right now is because we’re not burning regularly using little patches” [25].

Figure 5.

Cultural burning practice: slow, cool and low-intensity fire.

Regular cultural burning practices were interrupted in Victoria for almost two hundred years due to British colonization. This disruption of the social-ecological system resulted in a shift in the fire regime and increased bushfire risk [35,92]. In 2005, Atkinson argued for the reintroduction of traditional burning for land management as “one of the rights being asserted by the Yorta Yorta”. He pointed out the absence of controlled burning as one of the causes of large bushfires [55]. However, TEK needs to adapt to the contemporary socio-spatial context to cope with colonial legacy and climate change. The interacting process of healing the Country and healing people needs time for reconstruction and for setting the right bases for putting fire back in its natural environment. The first stage of cultural burning aims at resetting the contemporary landscapes shaped by the colonial impact to a balanced socio-ecological system.

Considering the Aboriginal epistemologies and recent cultural burning experiences, we can identify four key bases of cultural burning practices within the contemporary context. First, the physical, spiritual and cultural connection of people with the Country is the source of TEK and legitimizes burning activities for land management [29,91]. This connection embeds spirituality but also social organization and understanding the way in which the cultural landscape components interact and influence one another [92]. Traditional burning has its methods and protocols, but it cannot be a planned activity. Aboriginal people listen to the Country, in permanent dialogue and interact with the whole system when performing the cultural burn. Second, the customary and custodial responsibilities that Aboriginal people must care for all of the Country involve a commitment to reintegrate cultural fire into land management, and to decolonize and regenerate the landscape. This is a cultural responsibility with ancestors and with future generations [8,40,91]. Cultural burning practices are also a chance for intergenerational transmission of traditional knowledge. The exercise of all these responsibilities implies that cultural burning is a bottom-up initiative of TOs led by an Aboriginal fire knowledge holder, rather than a state-directed activity [39] (pp. 280–281). The third key base of Aboriginal fire is respecting Country (p. 90). In this sense, Djaara has developed the Forest Gardening Strategy (2022–2034) aimed at hearing, listening, understanding, and knowing what is required to heal Djandak in a changing climate [93]. This is the philosophy that Steffensen proposed: “burn country like you are gardening for food, and like you are living off the land to survive” [8]. Finally, creating cultural safety and building trust is required for conducting traditional burning practices and sharing TEK after two centuries of colonial abuse and exploitation of Aboriginal people’s cultural and material heritage.

3.2. Enabling Traditional Owners to Care for Country: Policy Process, Policy Outputs, and Policy Outcomes

Fire safety management in Victoria is a joint responsibility of Forest Fire Management Victoria (FFMVic) and the Country Fire Authority (CFA). FFMVic includes staff from the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA) (formerly Department of Energy, Land, Water and Planning—DEWLP), Parks Victoria, VicForests and Melbourne Water. Legally, FFMVic is responsible for all fire management on public land, including National Parks, State Parks and other crown land conservation areas, under the Forests Act 1958 [94] and in line with the Code of Practice for Bushfire Management on Public Land 2012 [95]. The CFA is a volunteer-based emergency service organization responsible for fire management on private lands.

Both FFMVic and CFA are implementing the Safer Together program [96], launched in late 2017 as the main policy instrument for wildfire risk management in Victoria. Safer Together aims at reducing bushfire risk for building safer and more resilient communities through integrated bushfire management. This innovative approach requires the engagement of local communities in close partnership for a proactive bushfire fuel management at the landscape scale. Bushfires don’t respect boundaries or land tenure, Safer Together understands that all kinds of knowledge and skills are needed to deal with bushfire risk. Hence, bushfire risk reduction aims to establish multiple links between fire and land management agencies, public and private lands, and Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. The fourth priority of Safer Together is “better knowledge = better decisions”. Here the program states: “Protecting people will always be our highest priority but we need to manage a healthy landscape for future generations”. This is a key connecting point between the agency fire management strategy and the Aboriginal fire culture.

DEECA defined six fire management agency regions across the state within the Safer Together program after the 2019–2020 Black Summer bushfires. The Dja Dja Wurrung and Yorta Yorta countries are comprised in the area of three DEECA regions: Hume, Loddon Mallee and Grampians. Each region has its own Strategic Bushfire Management Planning which is a long-term, participatory and iterative process to bring together land and fire managers, communities and stakeholders, including TOs groups, mainly for reducing bushfire risk through different fuel management options. The 2020 Bushfire Management Strategies are the main policy output of the Strategic Bushfire Management Planning [90]. The Bushfire Management Strategies recognize the potential of cultural burning to promote long-term fuel reduction outcomes, and the shared responsibility of Traditional Owner groups to achieve the overall objectives of fire management, namely community and ecosystem resilience. This policy instrument consists of a set of planned burning and other non-burn fuel management works for the six Victorian government regions, which are implemented by DEECA, Parks Victoria and CFA working together through the Joint Fuel Management Program (JFMP) [97].

CFA is highly committed to empowering Indigenous communities and incorporating traditional burning into FFMVic. CFA’s Koori Inclusion Action Plan (2014–2019) highlighted the need for stronger working relationships between the Koori community and CFA [98,99]. The word ‘Koori’ refers to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who live in Victoria. Every year since 2014, CFA staff and volunteers have attended cultural burning workshops in Victoria and other states aiming to share knowledge and experiences, and to learn from the cultural practices of Aboriginal communities of landscape management. In 2018, CFA appointed its first State-wide Cultural Heritage Advisor, and FFMVic enabled TOs to plan and lead cultural burns on public land across Victoria within the regulatory framework of The Victorian Traditional Owners Cultural Fire Strategy and the Joint Fuel Management Program.

The Joint Fuel Management Program was launched in 2016 to implement the Safer Together program, but it was updated after the 2019/2020 Black Summer fires in accordance with the 2020 Bushfire Management Strategies. The JFMP implements the objectives and associated performance measures for fire management and effective bushfire risk reduction set out in the Bushfire Management Strategies. This includes cultural burning practices, meaning “planned burns led by Traditional Owners on their Country as well as the use of cultural fire as a land management practice by Traditional Owners” [97].

Cultural burns are also framed within The Victorian Traditional Owner Cultural Fire Strategy that was launched by the Minister for Environment, Energy and Climate Change on 10 May 2019 [10]. The Victorian Traditional Owner Cultural Fire Strategy was the result of a top-down policy process, though it was built on local partnerships developed over five years between TOs and Government fire and land management agencies. The start of dialogue was based on the TOs assertiveness of their aspirations of fire and land management, and the Government’s investment in enabling an institutional change to authorize cultural burning. That was the first opportunity to connect and establish relationships between Aboriginal communities and fire agencies for mutual understanding and collaboration. Dja Dja Wurrung Corporation played a key role in this policy process through the conversations established with DELWP in 2015 during the implementation of the Dja Dja Wurrung Country Plan 2014–2034 [100]. Moreover, this document is the first bottom-up Aboriginal initiative in Victoria outlining the importance of their cultural heritage and advocating the role that fire plays in regeneration and in promoting the balance of species and ecosystems (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Key policy outputs of the Aboriginal fire culture and Government fire management agencies connection process.

According to JFMP, “cultural fire is fire deliberately put into the landscape led by the Traditional Owners of that Country for a variety of purposes, including ceremony, protection of cultural and natural assets, fuel reduction, regeneration and management of food and medicines, flora regeneration, fauna habitat protection and healing Country’s spirit”. Therefore, the JFMP recognizes that cultural burning practices are multipurpose and contribute to bushfire risk management through fuel reduction. This policy instrument provides a partnership scheme and funding support to enhance statewide cultural burning practices. The Cultural Funding Grants Program [101] launched by DELWP within Safer Together and framed within the JFMP is one of the main outcomes of the whole policy process to promote Aboriginal fire culture and its connection with bushfire risk management. This is an instrument to reinvigorate TOs led cultural burning practices for fuel reduction objectives in partnership with government agencies.

DELWP/DEECA and CFA provide funding, operational and planning support to TOs to perform cultural burning on the Country. Hence, the cultural burning agenda was promoted by the bottom-up initiatives of Aboriginal communities through different local partnerships with fire agencies, and then consolidated through Safer Together and The Victorian Traditional Owners Cultural Strategy. The inclusion of cultural burning within the JFMP is a result of three converging trends in the 2010s: first, the Victorian policy focus on reconciliation with Aboriginal communities; second, the Dja Dja Wurrung People’s initiatives to re-affirm their aspirations of land and fire management; and third, the social and political impact of the bushfires of Black Saturday 7 February 2009 that highlighted the potential of enabling Aboriginal fire culture for reducing bushfire risk [14].

The 2019–2020 catastrophic fire season enhanced the promotion of planned burns led by TOs within the JFMP. Indeed, the confluence of the 2019–2020 mega fires, the climate change awareness and the break for reflection during the pandemic lock-down acted as a catalyst for increased momentum in several top-down and bottom-up initiatives of Aboriginal communities relating to empowerment and cultural heritage revival.

In 2021 the Victorian TOs launched their Cultural Landscapes Strategy, funded by DEECA to support TO rights and interests in managing the Country according to their lore and customs [33]. The Victorian TOs Cultural Landscapes Strategy aims to enable cultural management practices, including cultural fire, for healing the Country within a similar partnership and funding model of the JFMP. The strategy recognizes the contribution of cultural practices to reduce wildfire risk. It also refers to forest gardening practices which are the target of the Forest Gardening Strategy [93] launched by Djaara in 2022 to empower everybody to be able to heal the Country. This is a bottom-up initiative, as were the Dja Dja Wurrung Country Plan and the Djandak Wi Program. All these Aboriginal initiatives to promote dialogue with government land and fire management agencies are an expression of the needed effort to correct the imbalance between a Western system and TEK. This is the main obstacle to effective reconnection and collaboration between two different ways of knowledge.

CFA is increasingly contributing to the facilitation of reconnecting Aboriginal fire culture and the wildfire management sector. The Diversity and Inclusion Strategy, 2023–2025 intends to build a solid partnership with the First Nations communities based on the principles of self-determination to enable deeper cultural exchange and knowledge sharing to the benefit of all Victorians [102]. This is also the purpose of the Green Paper on ‘Principles for enhanced collaboration between land and emergency management agencies and Indigenous Peoples” published in 2021 to stimulate discussion on reconciliation, collaboration and partnership with First Nations peoples [103].

Local government and some NGOs such as Landcare, Bush Heritage Australia and other groups on private land are also playing an increasing enabling role for traditional burning in Victoria. Some local councils are promoting cultural burns for ecological restoration and bushfire risk reduction. For example, Greater Shepparton City Council is collaborating with Parks Victoria and Yorta Yorta to perform cultural burning practices in Gemmill Swamp Reserve. Local Government Areas can have a closer and deeper connection to their local community and have been able to support burnings on private property through relationships with landowners.

3.3. Cultural Fire and Land Management in Transformed Landscapes

The first traditional burn supported by FFMVic within the JFMP was conducted on Sunday 14 May 2017 by the Dja Dja Wurrung People [89]. The cultural fire returned to the Country at Happy Tommy Track, just north of the central Victorian town of Maryborough. After the initial burn, seven subsequent burns varying in size between 8 and 235 ha were performed in 2018 within DELWP’s Fire Operations Plan for Dja Dja Wurrung Country [39].

The objectives of planned burns led by TOs within the JFMP consist of modifying the vegetation abundance across the planned area, to assist the promotion of native grasses—nodding saltbush (Einadia nutans ssp. nutans), wallaby grass (Rytidosperma caespitosum), bluebells (Wahlenbergia stricta)—and to restore cultural and ecological landscapes such as riverine woodland, treed swampy wetland, alluvial plains grassland, ironbark, dry forest and foothills forest. Aboriginal fire might also be planned for the control of invasive species and to reduce the speed and intensity of bushfires. Some planned burns led by TOs are intended to provide the highest level of localized protection to human life, property and community assets identified as highly valued within a Bushfire Management Zone [104,105,106].

The historic record of TOs burns and the number of planned burns led by Dja Dja Wurrung and Yorta Yorta peoples with the support of FFMVic and CFA for the period 2022–2025 remains low due to the strict requirements of the state agency regarding training, equipment and insurance (Table 1 and Figure 7). Cultural fire practitioners state that they are often unable to conduct Djandak Wi (Country fire) in accordance with TEK and the fire must conform to government fire agency standards. TOs must submit fire plans for approval to DEECA prior to conducting a burn. While this conformity means that insurance and liability are covered, it also confines Djandak Wi cultural practices to specific requirements and time frames of the government’s standards. Planned burn policies can mean the presence of many fire trucks and workers to ensure fire risk procedures are followed. Ultimately there is a sense among TOs that this reinforces European knowledge approaches [107].

Table 1.

Number of planned burns led by Dja Dja Wurrung and Yorta Yorta peoples within the JFMP with support from FFMVic and CFAs. Source: JFMP.

Figure 7.

Map of historic record and planned burns led by TOs in partnership with DEWLP/DEECA, in Dja Dja Wurrung and Bangarang/Yorta Yorta Country. Source: JFMP.

Woolshed Swamp is a significant site of planned burns led by TOs in partnership with DEWLP/DEECA. TOs burns to around 40 hectares have been conducted with a regular frequency, in 2019, 2020 and 2023, within a Bushfire Management Zone. The dominant vegetation in this crown land area consists of Black Box (Eucalyptus largiflorens), Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) and grasses. The TOs land management burn intends to modify the vegetation structure across the planned area to assist in the seeding and regeneration of rare and culturally important native grassland species in Northern Victoria: chocolate lilies (Arthropodium strictum), bulbine lilies (Bulbine bulbosa), lomandra (Lomandra filiformis) and dianella (Dianella longifolia). Despite the regulatory and legislative constraints, the TOs land management burns in Woolshed Swamp are contributing to the modification of the landscape structure towards a mosaic pattern and allowing TOs to share knowledge and get involved with fire agencies (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Cultural burn conducted in Woolshed Swamp by Amos Atkinson in collaboration with Djandak Barrapa Barrapa Land and Water Forest Fire Management, 2020.

Apart from fire agencies’ requirements and the trauma of dispossession and forced removal from the Country, Aboriginal fire practices are facing the challenges of transformed landscapes. One of the legacies of colonial systems is an over-cleared landscape pattern of cattle farms and croplands fragmented by fences and infrastructure (Figure 9). Landscapes were first disrupted and destabilized by colonization in the 1830s and 1840s. They then suffered a rapid ecological degradation from the 1880s to the 1920s followed by a drop in productivity in the mid-20th century that brought about a deeper transformation of land use and land management [20,40,108]. Furthermore, colonization introduced the Western fire exclusion culture built in the context of the European forest policy regimes within 19th century liberalism. Western fire suppression policies and Aboriginal peoples being prohibited from cultural practices of fire and land management are at the origin of scrub encroachment, grass ecosystems degradation, invasion of non-native species, and fuel load accumulation [1,36]. That led to a radical change in landscape structure and fire regimes [27,108,109].

Figure 9.

Landscape panorama of Dja Dja Wurrung Country from Mount Alexander.

After two centuries of fire exclusion, the return of cultural burning to the Country does not find pre-European cultural landscapes but rather a damaged colonial landscape. The right fire is needed to promote ecological regeneration [8]. However, cultural burning cannot be directly performed in these degraded landscapes. Reintroducing Djandak Wi looks to restore grassy ecosystems, landscape diversity and recover a mosaic pattern, and involves a transitory stage in the healing process that can take no less than ten years of TOs fire and land management [10].

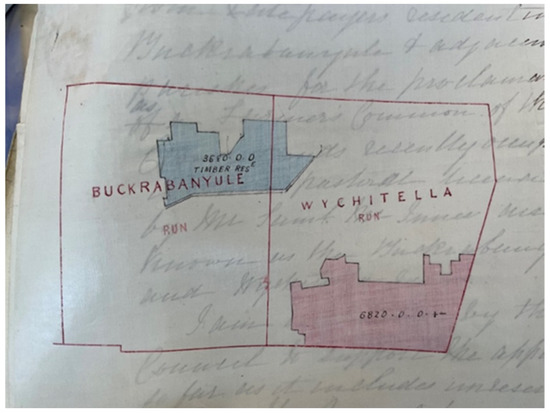

We have reconstructed the landscape transformation in Mount Buckrabanyule through archival documentary sources to assess the impact of colonial land use and land cover (LULC) changes on traditional cultural landscapes. As usually happened when Victoria was colonized during the early 1840s, the squatters selected ‘runs’ in the area ahead of any government-sanctioned subdivision [40,110,111] (Figure 10). This initial white occupation was quickly followed by a leasehold system that legalized land tenure. The ‘selection’ process was the breaking-up of the large pastoral leases and selling smaller plots to farmers for agriculture. Mount Buckrabanyule was part of the Buckrabanyule pastoral lease. During the first twenty to thirty years of the colonial occupation, land management consisted of tree felling, constructing dams and channels, and heavy livestock grazing with minimal clearing of land for cropping [112].

Figure 10.

Map of the Buckrabanyule run—a tracing included in correspondence to the Local Lands Board in the 1880s. Source: Public Record Office Victoria (PROV).

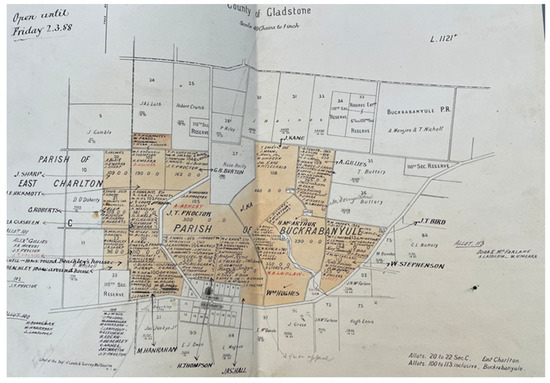

When selection happened around 1860, the township of Buckrabanyule was proclaimed, and Mount Buckrabanyule became a timber reservation (Figure 11). The timber reserve provided Europeans with timber for fencing, building, firewood and a money economy. It also protected access to freshwater from three springs for human use and brackish water in the gully for livestock. There was a grazing lease over the timber reserve, a relic of the squatters’ era when it had been a run.

Figure 11.

Part of the Parish of Buckrabanyule plan dated 1878. The timber reserve includes all of Mount Buckrabanyule and is about 4000 acres (1600 hectares). There are also two water reserves along the drainage line. Source: PROV. Available at: https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/88788E0F-F843-11E9-AE98-83EDAA61F92E?image=1 (accessed on 15 July 2023).

In 1880, some local farmers petitioned the Minister for Lands to have the timber reserve opened as a farmers’ common. The surveyor who visited the site in 1885 described the landscape in the following terms: “I have inspected the reserve referred to in attached petition, about 1/3 of this reserve consists of a rocky mount known as Mount Buckrabanyule. This mount is thinly timbered on the summit with stunted box trees, lower down near the foot of the mount the land is thickly timbered with box, the whole of the level part of the reserve is thickly timbered with box trees varying from 8 inches [20 cm] to 24 inches [60 cm] two feet [60 cm] from the ground, the timber is not of good quality and is apparently only useful for firewood” [113].

The petition for common land didn’t succeed, and the timber reserve was opened for selection. Finally, in 1888, the subdivision was established, the timber reserve was sold off, and Buckrabanyule became private land owned by several landholders. Judging by the number of names on each block of land, there was fierce competition for a piece of Mount Buckrabanyule which was followed by intense pastoral and agricultural land uses (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Plan of subdivision used in the sell off of the timber reserve, open for sale until Friday 2 March 1888. Source: PROV.

In the 1980s, Buckrabanyule suffered an invasive weed wheel cactus (Opuntia robusta) infestation which was reactivated in 2008 and became one of the most severe wheel cactus infestations in north-central Victoria. The Mexican native was introduced in the region in the early 20th century and constitutes one of the most invasive and problematic weeds in Australia [114].

In 2021, Bush Heritage Australia purchased a property of 452 ha in Buckrabanyule for cultural and nature conservation purposes. The aim of this NGO was to protect this site of cultural significance for Dja Dja Wurrung peoples from further subdivision and development, tackle the widespread and invasive wheel cactus infestation, and allow TOs access and healing the Country.

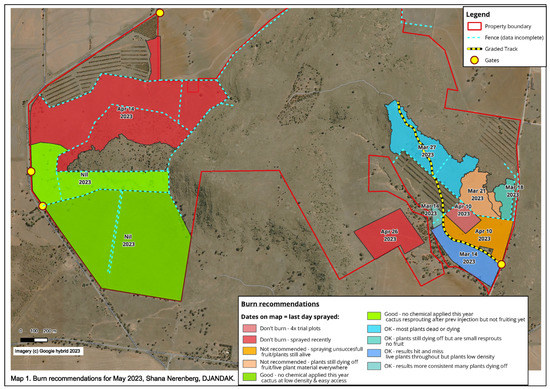

The cultural burn conducted in Mount Buckrabanyule led by Amos Atkinson on May 2023, is considered to be the return of traditional fire practices in this site after colonization. The main purpose of this cultural burn was to start the process of restoring the landscape and re-learning together to care for the Country. It was also an experimental traditional burning to try to control the invasive wheel cactus infestation (Figure 13). The traditional burn area size of around 6 ha was strategically distributed to achieve the proposed objectives of reducing the vulnerability of buildings and infrastructures to bushfires, activating the native vegetation regeneration, controlling the weed invasion, and getting bush tucker and medicine plants to thrive (Figure 14). Then, the burned area was seeded with kangaroo grass (Themeda) which is the traditional bread making grass that was a large part of the Aboriginal diet before invasion and colonization. In this case, the cultural burn is foreseen to be repeated every year to meet the objective of weed control.

Figure 13.

Cultural burn in Mount Buckrabanyule, 13 May 2023: (a) wheel cactus infestation before the cultural burn; (b) connecting people and fire; (c) removing the weeds; (d) landscape after the cultural burn.

Figure 14.

Buckrabanyule cultural burning design and recommendations, May 2023. Source: Djandak.

The cultural burn at Buckrabanyule is part of a holistic, long-term vision to strengthen the Aboriginal practice of reconnecting fire culture with landscape restoration aimed at sustainable land management and bushfire risk reduction. Beyond the ecological benefits, the social aspects are a main advantage of traditional burning in this site of spiritual significance in the Dja Dja Wurrung Country. This significant cultural burn was an opportunity to bring the Djandak group together, to walk on land with the community, to feel spiritual connections with the Country, and to transfer knowledge to younger generations. In the absence of a strict Western regulatory framework, the TOs felt safer getting involved in the process of cultural burning and sharing knowledge. The Aboriginal community empowerment process and the potential transferability of knowledge to other sites in the country are significant outcomes of this experience. Moreover, the Mount Buckrabanyule site offers the opportunity for Bush Heritage Australia to test the suitability of cultural burning practices for land management and to promote its reintroduction in its network of nature reserves around Australia.

The cultural burn conducted in 2020 in Gemmill Swamp was also a powerful experience of traditional fire management. The initiative came from a workshop on cultural burning organized by the Greater Shepparton City Council as a result of the dialogue established with the Bangarang/Yorta Yorta peoples. This collaboration was made possible by the role played by an Aboriginal local councilor, who facilitated the dialogue with TOs within the local government and acted as a mediator with Yorta Yorta Parks rangers. The cultural burn was performed in a council owned Red Gum woodland (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) to enhance native grasses and promote a landscape mosaic (Figure 15). This practice demonstrated the feasibility and potential of Aboriginal fire culture for ecological restoration and landscape maintenance. Furthermore, it contributed to building mutual trust in a climate of cultural safety setting the basis for reconnecting cultural burning and land management at the local level.

Figure 15.

Smoking ceremony at the cultural burn conducted in Gemmill Swamp by Amos Atkinson in collaboration with the Greater Shepparton City Council and Yorta Yorta Park rangers, 2020.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Controversial Fire: Is the Western Concept of Wildfire Risk Management Changing in Victoria?

According to Collof, “there is nothing more controversial in Environmental History than the subject of fire” [40] (p. 101). Aboriginal fire knowledge holders say that fire has moral resonances in the European tradition, “being associated with Hell and damnation” [37]. On the other hand, Collins has written about the “white Australian addition to fire-lighting” [115] (p. 107) when assessing major bushfires in Victoria—1851 Black Thursday, 1898 Red Tuesday, 1939 Black Friday, 1983 Ash Wednesday—and its influence in the social imaginary. The response of government agencies to emergency management has put in place legislation to control wildfires and implemented systematic fire-fighting policies to protect lives and assets [4,22,116]. This means that fire is managed as a discrete matter within the Western sectoral policy framework of separation, which is a major impediment to an integrated fire and land management from a broad-scale approach [70,83]

The use of fire by Aboriginal people for land management is a point of contention. The term fire-stick farming referring to cultural burning practices became popular with Jones, in 1969 [117], though it was first employed by Curr in 1883 [34,39,56,111]. From then on, many authors have recognized the role of traditional burning in sustainable fire and land management [4,36], and argued that Aboriginal fire-stick farming has played a significant role in maintaining the biodiversity of Australia [48]. Others have added to the discussion surrounding the environmental impact of Aboriginal landscape burning [109] and the ecological benefits of cultural fire practices [42]. King supported the opposite view in his report on the influence of colonization on forests and the prevalence of bushfires in Australia, based on journals and narrations of expeditions in the 19th century [118].

In addition, there are many controversies regarding the efficiency of prescribed burning and fire-fighting technology [22,119]. After the January 2003 catastrophic bushfires in northeastern Victoria, Collins stated: “the question of the use of fire to prevent fire stills confront us today” [115] (p. 57). Planned burns for fuel load control are consolidated in bushfire management policies. However, some authors are critical of the reductionist vision of planned burns solely for fuel reduction objectives and its implementation as a tactical management rather than a sustainable land management approach. Prescribed burns for fuel load reduction can be effective for a few years, but if not maintained, can also enhance the growth of flammable vegetation [120]. On the other hand, cultural burning could be more suitable for fuel load management in the rural-urban-forest interface, as a cool fire burns with less intrusion and lower smoke emissions than the prescribed burning.

Despite these ongoing controversies, the inquiries into the 2019/2020 Victorian fire season indicate a progressive change within the fire management sector towards introducing the fire recommendations of Indigenous communities, and actively engaging Indigenous communities in bushfire risk mitigation through consultations, observations, validation, advice and actual cultural burning practices. The Victorian Auditor-General’s Office (VAGO) recommendations for DELWP/DEECA and CFA highlight the importance of cultural burning practices for fuel management [63]. The Independent Inquiry of the Inspector-General for Emergency Management (IGEM) developed a discussion on the impact cultural burning can have on bushfire risk [121]. The inquiry into ecosystem declines of the Parliament of Victoria emphasized the need for training and accreditation in cultural burning and encouraged the Victorian Government to work in collaboration with TOs to offer accreditation in qualifications in conservation and Indigenous land management [122]. Finally, the Royal Commission into Natural Disaster Arrangements provided recognition and support for strengthening Indigenous land and fire management practices by acknowledging the benefits of a whole of community response to bushfires [123].

4.2. Environmental and Social Justice behind Cultural Burning Practices

The ongoing political process of introducing Aboriginal fire culture into bushfire risk management policy and practices is largely the result of initiatives of some Traditional Owner groups to keep caring for the Country within the framework of a consolidated Western system, and the willingness of fire agencies to support the return of cultural burning. However, bringing cultural burning back means not just acknowledging TOs, but implicitly requires the return of Aboriginal people to the Country, enabling the reconstruction of their socio-economic system and the devolution of their land tenure rights. Lynch and others argue that “at stake are fundamental issues of environmental sustainability and human dignity” [124] (p. 111).

Colonization brought about an abrupt disruption, especially between people and their places, which has deeply hurt their sense and physical ability to belong-to-place. It has also created high risk landscapes for Aboriginal people [78], accelerated the devastating impact of climate change and increased ecoanxiety due to disconnection and damage to the Country [125,126]. In this context, the Yorta Yorta people made use of their traditional knowledge to defend their Country from occupation [59]. The reintroduction of fire for land management in the Barmah and Millewa forests was merely one of the rights asserted by Yorta Yorta in the Native Title claim [40,56]. In contradiction to this, the controversial court judgement of 1998 denied Native Title arguing a loss of connection through abandonment of traditional laws and customs. The Federal Court Decision did not discourage Yorta Yorta people. On the contrary, in 2003, the Yorta Yorta Clans Group presented the final report of the Management Plan for the Yorta Yorta Cultural Environmental Heritage project [127]. It refers to seventeen separate attempts to obtain land and compensation made between 1860 and 1984. In this document, the Yorta Yorta people show a deep knowledge of their environmental heritage and the strong relationship maintained with their traditional Country based on customary law, including good fire practices.

There is a growing opportunity to reconnect Aboriginal cultural practices with Western land management systems. Aboriginal fire knowledge keepers and practitioners can play a crucial role in bringing back cultural know-how. According to May, “cultural burning represents a different model to distribute power over ignition” [39] (p. 280). Thus, the reintroduction of cultural burning practices for land management and bushfire risk reduction may contribute to the ongoing process of decolonization. The immediate work is that wherein civic and scientific knowledge enact an integrated approach to deal with this complex challenge of environmental and social justice [81].

Scientists and fire agencies are exploring how to empower and enable TOs to lead cultural fire and land management practices to improve landscape management and community resilience [88,98,99,128]. Engagement with Aboriginal people and communities within agencies is an opportunity for building a climate of mutual trust in a new socio-ecological context. However, it must be noted that the imbalance in the relationship between government agencies and Aboriginal communities is an important conditioning factor for effective connection and involves a risk of cultural assimilation for Indigenous technical knowledge. The danger of incorporating traditional burning into standard procedures is to deny the importance of its underlying processes. These instead require establishing mutual understanding and collaborative frameworks in the social-ecological landscape.

4.3. Landscape Resilience as ‘Common Ground’ within Victorian Fire Government Agencies and Aboriginal Communities

While Western science and fire agencies are recognizing the potential of traditional knowledge for wildfire risk management, there is a deep and compelling Aboriginal need and determination to re-invigorate cultural burning practices as a step along the way to decolonize landscapes while potentially preventing mega fire disasters [32,37,124]. From this perspective, we argue the notion of resilience is the key to reconnecting the fire culture of Aboriginal communities with contemporary wildfire risk management policies and structures.

The reconstruction of a healthy environment boosting landscape resilience and decreasing bushfire risk is critical for protecting not only the Victorian natural and cultural heritage, but also assets and human lives. Landscapes are complex and there are many factors that make landscapes vulnerable to fire, namely its degradation, the loss of traditional knowledge and the ongoing social conflicts. Resilience in this context needs to incorporate an adapting sequence. The landscape cannot bounce back to 1788 so we must acknowledge the social-ecological system as requiring small and big steps.

Restoring past damage to the Country is a huge, complex task that requires collective learning for a renewed adapted land and fire management system. Fire agencies are evolving from local partnerships towards the creation of a state-wide governance group for cultural burning. This mechanism would allow for a collaborative regulatory framework to be defined for implementing the agenda of cultural burning practices. Furthermore, the governance group could acknowledge fire knowledge holders and provide the leadership to better articulate the existing plurality of cultural burning practices in Victoria.

Australian Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people can reimagine living with fire and living in a dramatically altering landscape [129]. Adaptation and adaptive capacity are required to progressively focus and improve emergency preparedness to manage bushfire crises in the context of climate change. This is a short to long-term approach toward landscape resilience and emergency management that requires creating new opportunities to modify fire behavior and reduce communities’ vulnerability to wildfire risk.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we have shown that cultural burning can contribute to wildfire risk mitigation in the contemporary environment by creating a resilient landscape less prone to catastrophic fire [93]. Indeed, Aboriginal fire culture is an important contributor to bushfire risk reduction that can provide a direct benefit to the entire community, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal [90].

Our findings suggest that combining historical analysis with the social-ecological present provides a suitable framework for a better understanding of contemporary challenges and opportunities to manage fire safety in the context of climate change. In fact, connecting Aboriginal fire culture and government fire agencies is more than a paradigm shift. This is about thinking differently, reconceptualizing fire, changing social mindsets and modifying the policy framework to open a new shared journey [8,82]—all of this takes time, trust and willingness to learn.

Victoria is involved in an ongoing process for building a renewed integrated fire management approach including cultural burning. Since 2010 both fire agencies and Aboriginal peoples have been promoting dialogue and collaborating. However, the imbalance between government agencies and Aboriginal communities causes a serious risk of domination of the strongest position over the weakest position. The planned burns led by TOs in the Joint Fuel Management Program cannot be considered real cultural burns, but they are an important step to looking at planned burns through a more culturally sensitive lens.

The confrontation of the colonial legacy with Aboriginal cultural practice is a major impediment to connecting bushfire risk management with traditional burning practices, as it creates an unbalanced position among state agencies and Aboriginal communities. The bottom-up initiatives of Aboriginal communities with the support of local communities and private owners show the need to correct the dominant position of Western systems within public policies. That is the main obstacle to an effective connection and collaboration between two different ways of knowing and operating.

Another impeding factor for reconnecting the fire culture of Aboriginal communities with contemporary wildfire risk management is the different ways of thinking and acting between the Western system and Aboriginal customary law and practice [81]. There is a clear confrontation between control in planned burns versus connection in cultural burns. The central idea of planned burns is to control fire, while the aim of cultural burning is putting the fire back into its natural environment and allowing the Country to determine what needs to be burnt. The objectives of planned burns also differ from the purposes of cultural burns. Planned burns look at reducing fuel load, while cultural burns aim at healing, restoring and decolonizing the Country.

The key issues for a transition towards a new paradigm that incorporates Aboriginal fire knowledge within transformed landscape management are reframing the connections and recognizing Native Title, empowering Aboriginal communities and engaging a long-term collective learning process in the fire agencies [107]. Both wildfire risk management and traditional burning need to change together to adapt to the new environmental context and collaborate for mutual and common benefit. Establishing a climate of reciprocal reliability is critical for trust to be established between all parties, the TOs to share knowledge, and the Government agencies to reintroduce cultural burning for land and fire management.

Fire cannot be seen as separate from the overall political, social and legal systems. The incorporation of TEK in wildfire risk management demands deliberative democratic reforms within the fire services and among the political processes that regulate their funding. Furthermore, it requires to negotiate a treaty for the land [34] (p. 34).

Government agencies and Aboriginal peoples can relearn together to live in the Country with fire. That requires maintaining a continuous dialogue to create opportunities to manage fire safety by healing the Country: meaning restoring landscape resilience. It involves a long-shared journey towards fire safety by improving social-environmental justice at a time when climate change is challenging the way authorities respond to crises.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and C.M.-M.; methodology, A.A. and C.M.-M.; formal analysis, C.M.-M.; cultural burning practices, A.A.; investigation, A.A. and C.M.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.-M.; writing—review and editing, A.A. and C.M.-M.; funding acquisition, C.M.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport under the Salvador Madariaga program, grant numbers PRX18/00426 and PRX22/00462; and the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitivity, project number CSO2017-87614-P.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Amos Atkinson acknowledges all his Ancestors who have come before him. He also acknowledges both Countries of Dja Dja Wurrung Nation and Bangarang/Yorta Yorta Nation where the study has taken place on. Amos Atkinson is grateful to RMIT University, Michael Bourke, Victor Steffenson, Olivia Guntarik, Nathan Wong and Aunty Vicki Couzens. Cristina Montiel acknowledges Katie Holmes for hosting her research stay of 2023 in the Centre for the Study of the Inland of La Trobe University, and Ruth Beilin who hosted the research stays in 2018 and 2020 in the School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences at the University of Melbourne. She gratefully acknowledges the experts and academics who contributed to this study: Michael Sherwen, Roger Strickland, Owen Gooding, Susan Lawrence, Chris Johnson, Evan B. Lewis, Jim McLennan, Karen Reid, Rebecca Walker, Garry Detez, Darren Wandin, Corinne Bowen, Nelson Aldridge, Sam Piper, Lisa Keedle, Nina Roberts and Simone L. Blair. Cristina Montiel also expresses her gratitude to the members of the Environmental History Reading Group of La Trobe University, especially Karen Twigg, for their comments and encouragement in this research. The authors would like to thank Ruth Beilin, Susan Lawrence, Rebecca Walker and Roger Strickland for reviewing the manuscript, and Estrella E. Melero-Blanca for generating the maps. We also thank the reviewers and academic editors for their constructive and valuable comments which have enabled us to improve the original manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Filkov, A.; Ngo, T.; Matthews, S.; Telfer, S.; Penman, T.D. Impact of Australia’s catastrophic 2019/20 bushfire season on communities and environment. Retrospective analysis and current trends. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 2020, 1, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.; Bradstock, R.; Clarke, H.; Clarke, M.F.; Nolan, R.H.; Penman, T. The 2019/2020 mega-fires exposed Australian ecosystems to an unprecedent extent of high-severity fire. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 044029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.; Taylor, C. New spatial analyses of Australian wildfires highlight the need for new fire, resource, and conservation policies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 12481–12485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, M.S.; Romano, A.; Connor, S.; Mariani, M.; Maezumi, S.Y. Catastrophic bushfires, Indigenous fire knowledge and reframing science in southeast Australia. Fire 2021, 4, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.; Gardner, S.; Jame, P.; Komesaroff, P. (Eds.) Continent Aflame. Responses to an Australian Catastrophe; Palaver: Armadale, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, B.; Markham, F.; Weir, J.K. Aboriginal Peoples and the Response to the 2019–2020 Bushfires; Working Paper No. 134/2020; Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson-Hoyle, S.; Ignace, R.E.; Ignace, M.B.; Hagerman, S.M.; Daniels, L.D.; Copes-Gerbitz, K. Walking on two legs: A pathway of Indigenous restoration and reconciliation in fire-adapted landscapes. Restor. Ecol. 2022, 30, e13566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffensen, V. Fire Country. How Indigenous Fire Management Could Help Australia; Hardie Grant Travel: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Firesticks Alliance. Available online: https://www.firesticks.org.au/community/alliance/ (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- The Victorian Traditional Owner Cultural Fire Knowledge Group. The Victorian Traditional Owner Cultural Fire Strategy. 2019. Available online: https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/media/6817/fireplusstrategyplusfinal.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Kelly, L.T.; Gijohann, K.M.; Duane, A.; Aquilué, N.; Archibald, S.; Batllori, E.; Bennet, A.F.; Buckland, S.T.; Canelles, Q.; Clarke, M.F.; et al. Fire and biodiversity in the Anthropocene. Science 2020, 370, eabb0355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.; Taylor, C.; Blanchard, W. Empirical analyses of the factors influencing fire severity in southeastern Australia. Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, P.; Moradkhani, H.; Abbaszadeh, P.; Kiem, A.S.; Engstrom, J.; Keelings, D.; Sharma, A. Causes of the widespread 2019–2020 Australian bushfire season. Earth’s Future 2020, 8, e2020EF001671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, B.; Pascoe, S.; McLeod, R. The 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission Final Report: Summary, July 2010; Government Printer for the State of Victoria, PP No. 332–Session 2006-10; Parliament of Victoria: Melbourne, Australia, 2010. Available online: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2010-08/apo-nid22187.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2023).