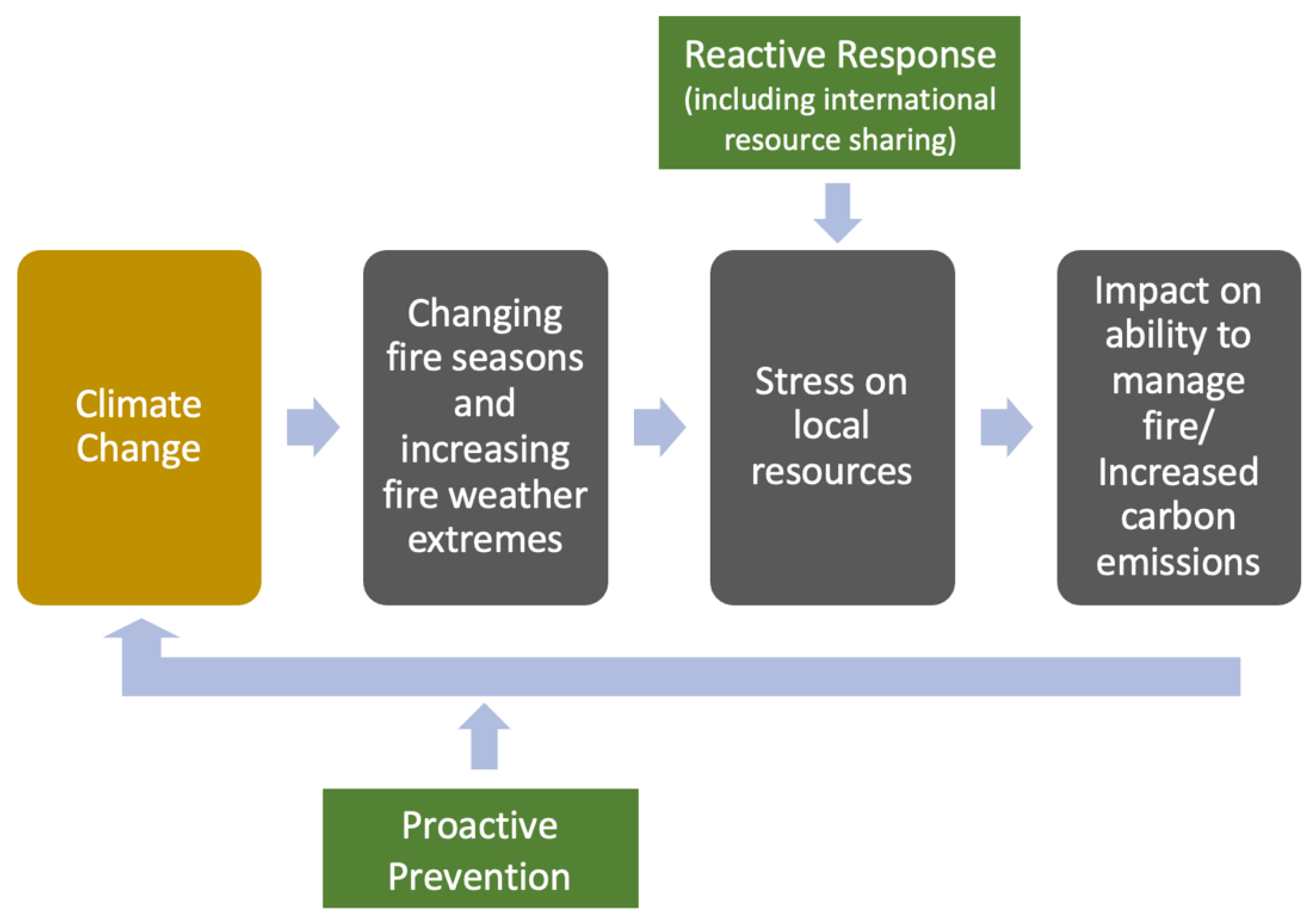

The Role of International Resource Sharing Arrangements in Managing Fire in the Face of Climate Change

Abstract

:1. Introduction

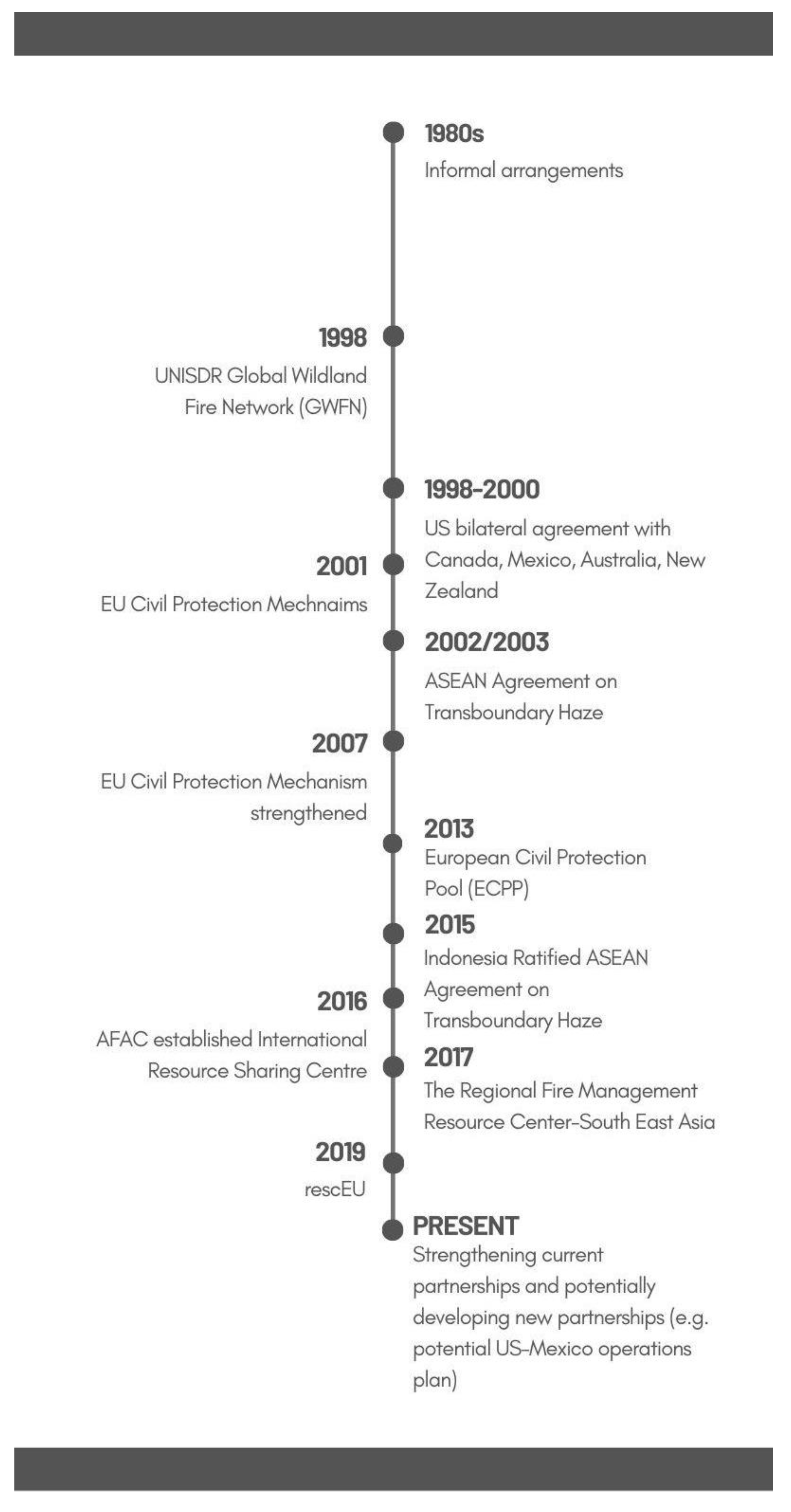

1.1. History of International Collaboration Agreements

1.1.1. Global

1.1.2. “Big Three”: US, Canada, Australia

1.1.3. European Union

1.1.4. Southeast Asia/ASEAN

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

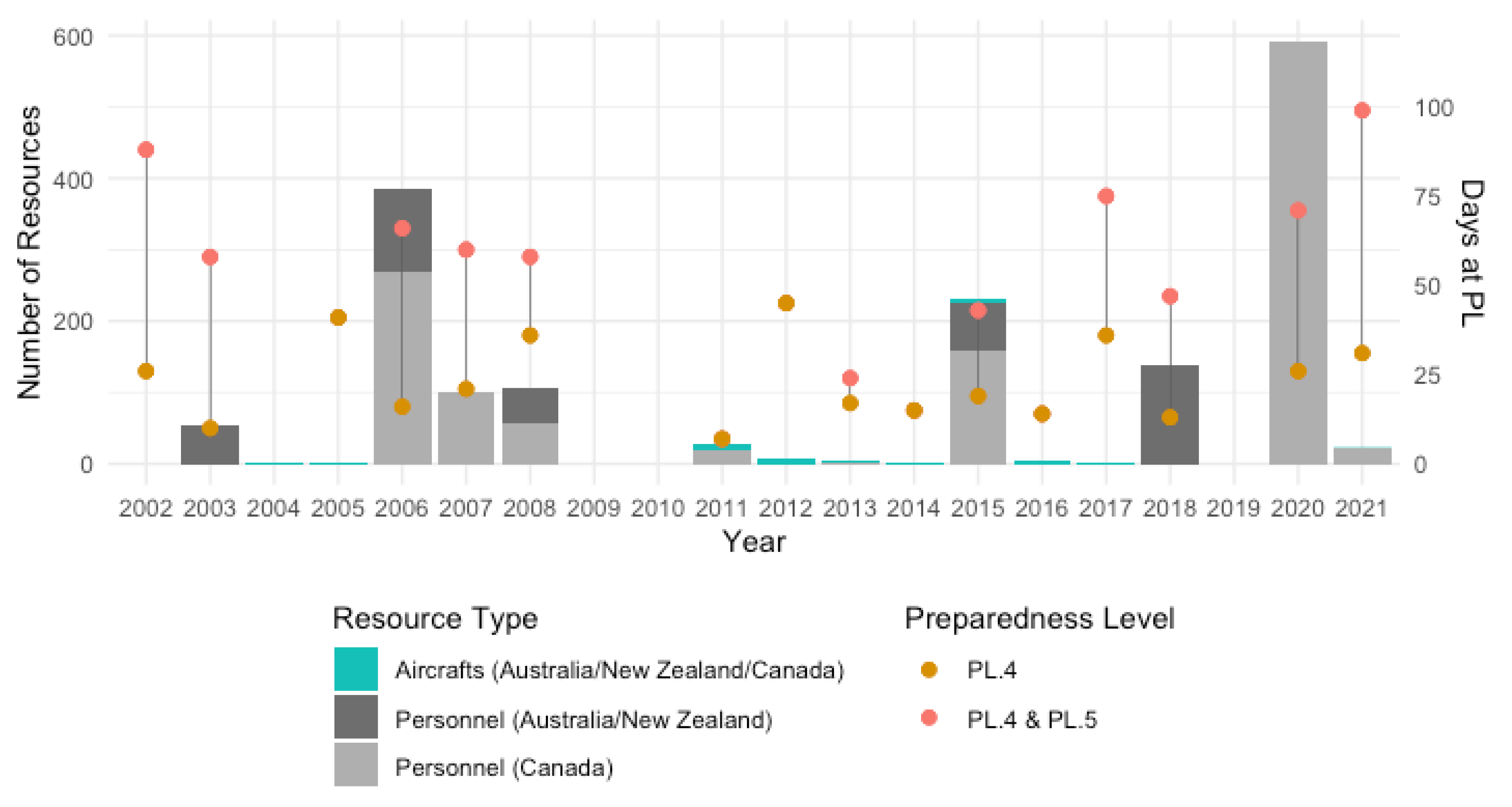

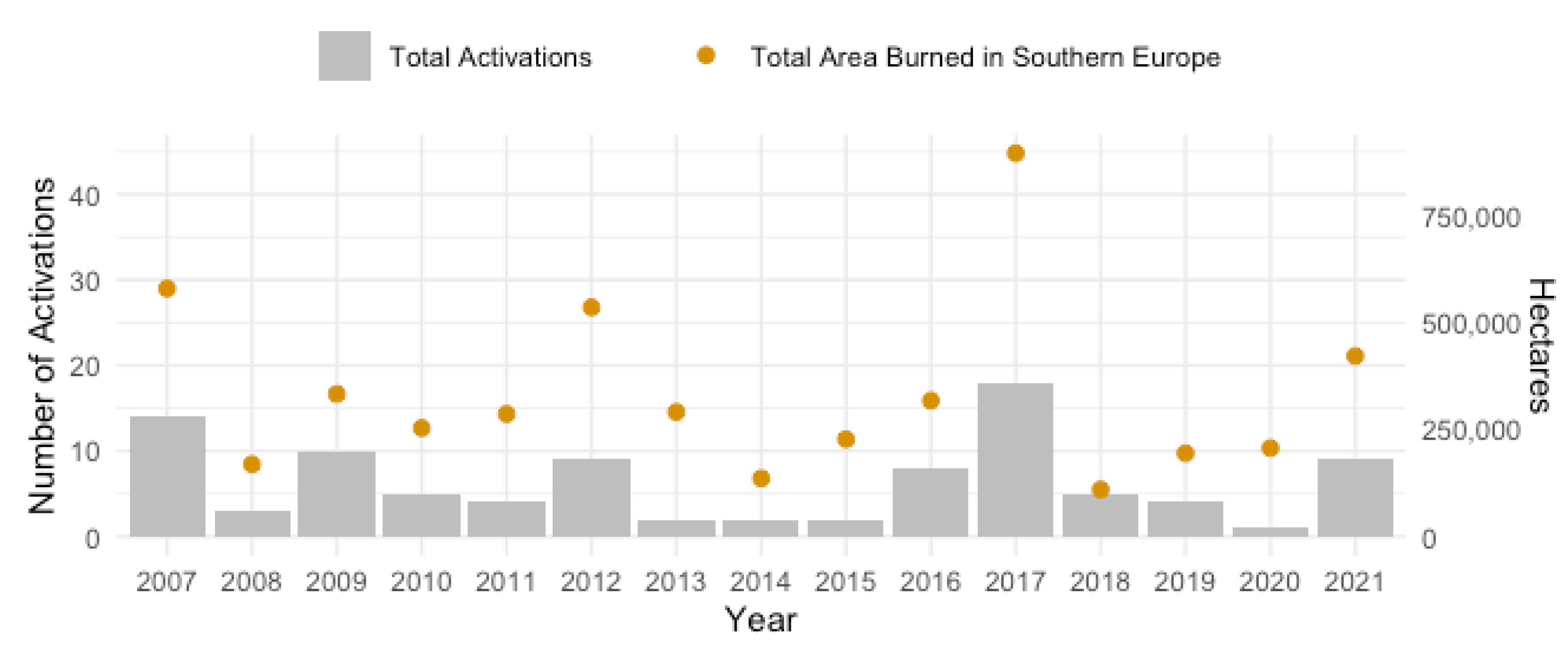

3.1. Illustrative International Resource Sharing Figures

3.2. Case Study of Fire Management in Southeast Asia

3.3. Evaluation of Sharing Models

“yeah yeah, it is definitely useful because there is no country that can have all the resources they need to deal with every situation. It just, you know, it wouldn’t be feasible, it wouldn’t be cost effective. They’d have what’s been called rust out because they’re, you know, on slow fire seasons. You know idle hands make for you know those, those cliches so. But when things are really bad, there needs to be a mechanism to get help from your neighbors, if you will, and these international agreements are just that….that assistance from their point of view was critical there’s no way they could have managed that fire season on their own.”

“It has proven that it is very useful and effective and it’s quick, and by sharing the resources it’s better, it’s cost effective because … by sharing, we can reduce the number and you can use them more effectively, so it’s even cost reduction…international resource sharing it’s only one way to be prepared for the for the biggest emergency, because there is no way that each country could build independently a response system. It is just going to be too expensive, it’s going to be too big a burden for one country to handle it.”

“I don’t think it’s practical for anyone to keep a standing army of people who are only ever used once every ten years. So there’s a clear logic in sharing resources internationally and it, it helps those people who end up deploying. It helps them grow. It’s a great opportunity for people to see how things are done elsewhere in the world. Every time I send people, they come back saying, look, it was fantastic, I learned so much, and you know we were also able to share some of the things that we do that maybe people haven’t encountered before that’s a really good idea.”

3.3.1. United States/Canada/Australia

Strength and Role

Barriers

3.3.2. European Union

Strength and Role

Barriers

3.3.3. Southeast Asia/ASEAN

Barriers

3.3.4. Climate Change Impact on Resource Sharing

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Protocol

- Thank you for making this time for us

- Introductions

- Background on the project

- What we hope to accomplish in this meeting

- ○

- I will be asking you a set of interview questions that we have prepared

- ○

- Our questions are organized around resource sharing decision-making for fire suppression in terms of both making requests for resources or assistance for fire suppression and providing personnel and equipment to requesting countries

- What is your involvement and/or your organization’s involvement with international resource sharing for fire suppression?

- How has international resource sharing evolved over time for your country/region/organization? Have fire seasons lengthened in your location and has there been a greater need or demand for international resource sharing? (If country) Is your location making more demands/requests now than in the past? (If multilateral organization or country) Are others making more requests of you than in the past?

- (If country) Does international resource sharing affect your country’s decisions around planning and pre-positioning resources ahead of the season? Does your country have a certain amount of resources that should be on hand at all times prohibiting or limiting when resources are able to be sent abroad? (If multilateral organization) How do you determine how many resources should be pooled or available prior to a fire season?

- How do you go about making requests (if country)? Is it a hotline? A web form? Do you call your counterpart? Other? How do others make requests of you (if multilateral organization or country)?

- What are the circumstances under which requests for international assistance and back up are made? (E.g., Last resort, shared pool of assets.)

- What information do you utilize to make decisions about:

- international resource sharing requests? (Database, conditions necessary for resource sharing, political, other?)

- Providing resources to partner nations?

- What type of characteristics of fire seasons are likely to lead to international resource sharing requests? (E.g., Large area burned, large number of fires, location of fires, flame length, etc.)

- What is the administrative process for requesting and providing international resource sharing assistance for fire management? (Communication process and tools, conditions, levels of authority, and types of approval required.)

- For bilateral agreements, how do you decide which country to request resources from first?

- What are the strengths of the international resource sharing program that you are involved with?

- What are the weaknesses and/or barriers for the international resource sharing program?

- How can international resource sharing be improved?

- What do you believe should be the role of international resource sharing in the future? Does the projected impact of climate change and/or simultaneity affect your decision making?

Appendix B. Data and Methodology for International Resource Sharing Trends Figures and Case Study

References

- Andela, N.; Morton, D.C.; Giglio, L.; Chen, Y.; van der Werf, G.R.; Kasibhatla, P.S.; DeFries, R.S.; Collatz, G.J.; Hantson, S.; Kloster, S.; et al. A Human-Driven Decline in Global Burned Area. Science 2017, 356, 1356–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jolly, W.M.; Cochrane, M.A.; Freeborn, P.H.; Holden, Z.A.; Brown, T.J.; Williamson, G.J.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Climate-Induced Variations in Global Wildfire Danger from 1979 to 2013. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Kolden, C.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Johnston, F.H.; van der Werf, G.R.; Flannigan, M. Vegetation Fires in the Anthropocene. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmeier-Young, M.C.; Gillett, N.P.; Zwiers, F.W.; Cannon, A.J.; Anslow, F.S. Attribution of the Influence of Human-Induced Climate Change on an Extreme Fire Season. Earths Future 2019, 7, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuera, P.E.; Abatzoglou, J.T. Record-setting Climate Enabled the Extraordinary 2020 Fire Season in the Western United States. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podschwit, H.; Cullen, A. Patterns and Trends in Simultaneous Wildfire Activity in the United States from 1984 to 2015. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2020, 29, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Juang, C.S.; Williams, A.P.; Kolden, C.A.; Westerling, A.L. Increasing Synchronous Fire Danger in Forests of the Western United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL091377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Williams, A.P.; Barbero, R. Global Emergence of Anthropogenic Climate Change in Fire Weather Indices. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podschwit, H.; Larkin, N.; Steel, E.; Cullen, A.; Alvarado, E. Multi-Model Forecasts of Very-Large Fire Occurences during the End of the 21st Century. Climate 2018, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jain, P.; Castellanos-Acuna, D.; Coogan, S.C.P.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Flannigan, M.D. Observed Increases in Extreme Fire Weather Driven by Atmospheric Humidity and Temperature. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, S.J.; Hessburg, P.F.; Hagmann, R.K.; Povak, N.A.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Hurteau, M.D.; Kane, V.R.; Keane, R.E.; Kobziar, L.N.; Kolden, C.A.; et al. Adapting Western North American Forests to Climate Change and Wildfires: 10 Common Questions. Ecol. Appl. 2021, 31, e02433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wotton, B.M.; Flannigan, M.D.; Marshall, G.A. Potential Climate Change Impacts on Fire Intensity and Key Wildfire Suppression Thresholds in Canada. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 095003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, M.; Cantin, A.S.; de Groot, W.J.; Wotton, M.; Newbery, A.; Gowman, L.M. Global Wildland Fire Season Severity in the 21st Century. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 294, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, S.J.; Stevens-Rumann, C.S.; Hessburg, P.F. Tamm Review: Shifting Global Fire Regimes: Lessons from Reburns and Research Needs. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 396, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Miao, C.; Hanel, M.; Borthwick, A.G.L.; Duan, Q.; Ji, D.; Li, H. Global Heat Stress on Health, Wildfires, and Agricultural Crops under Different Levels of Climate Warming. Environ. Int. 2019, 128, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, C.R.; Innes, J.L. Climatic Change and Fire Potential in South-Central British Columbia, Canada. Glob. Change Biol. 2008, 14, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriondo, M.; Good, P.; Durao, R.; Bindi, M.; Giannakopoulos, C.; Corte-Real, J. Potential Impact of Climate Change on Fire Risk in the Mediterranean Area. Clim. Res. 2006, 31, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, M.D.; Krawchuk, M.A.; de Groot, W.J.; Wotton, B.M.; Gowman, L.M. Implications of Changing Climate for Global Wildland Fire. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, A.C.; Axe, T.; Podschwit, H. High-Severity Wildfire Potential—Associating Meteorology, Climate, Resource Demand and Wildfire Activity with Preparedness Levels. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2021, 30, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, N.L.; Gibbs, D.A.; Baccini, A.; Birdsey, R.A.; de Bruin, S.; Farina, M.; Fatoyinbo, L.; Hansen, M.C.; Herold, M.; Houghton, R.A.; et al. Global Maps of Twenty-First Century Forest Carbon Fluxes. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtman, R.M.; Montgomery, C.A.; Gagnon, A.R.; Calkin, D.E.; Dietterich, T.G.; McGregor, S.; Crowley, M. Allowing a Wildfire to Burn: Estimating the Effect on Future Fire Suppression Costs. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2013, 22, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerr, S.H.; Santín, C. Global Trends in Wildfire and Its Impacts: Perceptions versus Realities in a Changing World. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Williamson, G.J.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Kolden, C.A.; Cochrane, M.A.; Smith, A.M.S. Human Exposure and Sensitivity to Globally Extreme Wildfire Events. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 0058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronto, L. The Global Wildland Fire Network: 2016 in Review. Wildfire Mag. 2016, 25, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Goldammer, J.G. (Ed.) Vegetation Fires and Global Change: Challenges for Concerted International Action, A White Paper Directed to the United Nations and International Organizations; Global Fire Monitoring Center (GFMC): Remagen-Oberwinter, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-3-941300-78-1. [Google Scholar]

- GFMC. Global Fire Monitoring Center (GFMC): GFMC Mandates; GFMC: Freiburg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- USDA. A Global Landscape Fire Challenges: A Decade of Progress. Fire Manag. Today 2019, 77, 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dorrington, G. Global Wildfire Protection: A Proposal for an International Shared Wildfire Fighting Aircraft Fleet and Satellite Early Warning System; World Engineers Convention Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2020; ISBN 978-1-925627-25-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tymstra, C.; Stocks, B.J.; Cai, X.; Flannigan, M.D. Wildfire Management in Canada: Review, Challenges and Opportunities. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 5, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIFC. National Wildland Fire Preparedness Levels; NIFC: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Considine, P. Cross-Border Response and Resource Management. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2019, 34, 8. [Google Scholar]

- European Comission. European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations-Forest Fires Fact Sheet; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pierard, G.; Jarvis, A. Study on Wild Fire Fighting Resources Sharing Models; European Policy Evaluation Consortium (EPEC): Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- European Comission. RescEU: Commission Welcomes Provisional Agreement to Strengthen EU Civil Protection; Press Corner; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- DG ECHO. Annual Activity Report 2021: Directorate General for Civil Protection and Humanitarian AID Opeartions; European Union, Ed.; DG ECHO: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Comission. Regulation (EU) 2021/836 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2021 Amending Decision No 1313/2013/EU on a Union Civil Protection Mechanism; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The ASEAN Secretariat. ASEAN Standard Operating Procedure for Monitoring Assessment and Joint Emergency Response; The ASEAN Secretariat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J. Transboundary Perspectives on Managing Indonesia’s Fires. J. Environ. Dev. 2006, 15, 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldammer, J.G. International Cooperation in Wildland Fire Management. Unasylva 2004, 55, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, J.S.; Bobbe, T.; Ray, N.; Witt, R.G.; Singh, A. Wildland Fires and the Environment: A Global Synthesis; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 1999; ISBN 92-807-1742-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vadrevu, K.P.; Lasko, K.; Giglio, L.; Schroeder, W.; Biswas, S.; Justice, C. Trends in Vegetation Fires in South and Southeast Asian Countries. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, N.L.; Minnemeyer, S.; Stolle, F.; Payne, O. Indonesia’s Fire Outbreaks Producing More Daily Emissions than Entire US Economy; Insights World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tacconi, L. Preventing Fires and Haze in Southeast Asia. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiely, L.; Spracklen, D.V.; Arnold, S.R.; Papargyropoulou, E.; Conibear, L.; Wiedinmyer, C.; Knote, C.; Adrianto, H.A. Assessing Costs of Indonesian Fires and the Benefits of Restoring Peatland. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jong, H.N. RI Refuses’s Singapore’s Help in Forest Fires. The Jakarta Post, 12 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rayda, N. Firefighters on Frontline of Indonesia’s Peatland Blaze Face Uphill Battle. Channel News Asia, 19 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.B.D. Indonesia President Threatens to Sack Fire Fighters If Forest Blazes Not Tackled. Reuters, 6 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, S. Singapore Offers Help to Tackle Illegal Indonesia Forest Fires. Financial Times, 16 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FFMG; FMWG. North American Study Tour to Australia and New Zealand; Fire Management Working Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- USDA Forest Service Fire & Aviation; DOI Office of Wildland Fire. United States Interagency Support to Australia After Action Review 2019–2020 Bushfires; USDA Forest Service Fire & Aviation: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- USDA Forest Service Fire & Aviation. Fact Sheet: International Agreements for Fire Management Support; USDA Forest Service Fire & Aviation: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FFMG; FMWG. International Symposium on Wildfire Management; North American Forestry Commission, Fire Management Working Group (FMWG): Park City Utah, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ekengren, M.; Matzén, N.; Rhinard, M.; Svantesson, M. Solidarity or Sovereignty? EU Cooperation in Civil Protection. J. Eur. Integr. 2006, 28, 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICF. Evaluation of Civil Protection Mechanism—Case Study Report—Forest Fires in Europe; ICF Consulting Services Ltd, Ed.; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Erikesn, C.; Hauri, A.; Thiel, J.; Scharte, B. An Evaluation of Switzerland Becoming a Participating State of the European Union Civil Protection Mechanism; ETH Zurich Research Collection Center for Security Studies: Zurich, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ICF. Interim Evaluation of the Union Civil Protectin Mechanism, 2014–2016; European Comission, Directorate-General for Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Monet, J.-P.; Pierre, S.; Pirone, S.; Castellnou, M.; Dumas, M.; Lampris, C. Civil Protection in Europe: Towards a Unified Command System? Lessons Learned, Studies and Ideas About Change Management Sté Phane Poyau Landes Fire Department. Eur. Command. Syst. 2020, 202, 315–325. [Google Scholar]

- Varkkey, H. Regional Cooperation, Patronage and the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution. Int. Environ. Agreem. Polit. Law Econ. 2014, 14, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, D. After Indonesia’s Ratification: The ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution and Its Effectiveness as a Regional Environmental Governance Tool. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Aff. 2015, 34, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, A.; Lee, T. Delayed Ratification in Environmental Regimes: Indonesia’s Ratification of the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution. Pac. Rev. 2021, 34, 1108–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.T.Y. The ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution: Exploring Mediation as a Way Forward. Asia Pac. J. Environ. Law 2017, 20, 138–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, T. Public Concerns about Transboundary Haze: A Comparison of Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 25, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.J.; Savage, V.R. Southeast Asia’s Transboundary Haze Pollution: Unravelling the Inconvenient Truth. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2019, 60, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconi, L.; Jotzo, F.; Grafton, R.Q. Local Causes, Regional Co-Operation and Global Financing for Environmental Problems: The Case of Southeast Asian Haze Pollution. Int. Environ. Agreem. Polit. Law Econ. 2008, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.M.; Jones, R.G.; Narisma, G.T.; Alves, L.M.; Amjad, M.; Gorodetskaya, I.V.; Grose, M.; Klutse, N.A.B.; Krakovska, S.; Li, J.; et al. Atlas. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Pean, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 1927–2058. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Pean, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.; Sims, M.; Burns, D.; Lyons, K. What COP26 Means for Forests and the Climate; Insights World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jong, H.N. Indoneisa’s New Epicenter for Forest Fires Shifts Away from Sumatra and Borneo. Mongbay, 29 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, A.; Krishnamoorti, R. Understanding the Greenhouse Gas Impact of Deforestation Fires in Indonesia and Brazil in 2019 and 2020. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 799632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinne, F.-N.; Burns, J.; Kant, P.; Flannigan, M.D.; Kleine, M.; de Groot, B.; Wotton, D.M. (Eds.) Global Fire Challenges in a Warming World: Summary Note of a Global Expert WOrkshop on FIre and CLimate Change; IUFRO Occa; IUFRO: Vienna, Austria, 2018; ISBN 978-3-903258-13-6. [Google Scholar]

| Region | Agreement | Type of Agreement | Sub-Arrangements to Facilitate Resource Sharing |

|---|---|---|---|

| The United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand | Australia/New Zealand/US International Agreement (2000); Canada/US Northwest Wildland Fire Protection Agreement (1998) | Bilateral | Operating Plans |

| The United States (states) and Canada (provinces) | Regional Forest Fire Protection Compacts | Multilateral (local international) | (beyond the scope of this paper) |

| Europe/European Union | Sharing amongst European nations | Bilateral | (beyond the scope of this paper) |

| European Union Civil Protection Mechanism (2001) | Multilateral | European Civil Protection Pool, rescEU, cost sharing | |

| Southeast Asia/ASEAN | Humanitarian aid from aid agencies or European Union Civil Protection Mechanism | Bilateral | |

| ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze (2002/2003) | Legal Environmental Agreement | A complementary mechanism to facilitate capacity building and information sharing is the Regional Fire Management Resource Center–Southeast Asia |

| Agency | Country/Region | Number |

|---|---|---|

| National Multi-Agency Coordination Group (NMAC) | United States | (2) |

| Department of the Interior | United States | (4) |

| US Forest Service, USDA | United States | (2) |

| National Interagency Coordination Center (NICC)/National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) | United States | (2) |

| Australasian Fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council (AFAC) | Australia and New Zealand | (1) |

| Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Center (CIFFC) | Canada | (1) |

| Emergency Response Coordination Center, European Commission-DG ECHO | European Union | (1) |

| Regional Fire Management Resource Center | Southeast Asia | (1) |

| Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) | Indonesia/Global | (1) |

| Global Fire Monitoring Center (GFMC) | Global | (1) |

| Total Representatives Spoken With | 15 |

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US to Australia and New Zealand | ||||||||||||

| US to Canada | ||||||||||||

| Canada to US | ||||||||||||

| Australia and New Zealand to US | ||||||||||||

| EU Civil Protection Mechanism activated >3 times |

| Strengths | Weaknesses/Challenges/Barriers | Future Directions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral agreements Australia, Canada, United States |

|

|

|

| EU Civil Protection Mechanism |

|

|

|

| Southeast Asia/Diplomatic Missions |

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bloem, S.; Cullen, A.C.; Mearns, L.O.; Abatzoglou, J.T. The Role of International Resource Sharing Arrangements in Managing Fire in the Face of Climate Change. Fire 2022, 5, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5040088

Bloem S, Cullen AC, Mearns LO, Abatzoglou JT. The Role of International Resource Sharing Arrangements in Managing Fire in the Face of Climate Change. Fire. 2022; 5(4):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5040088

Chicago/Turabian StyleBloem, Sunniva, Alison C. Cullen, Linda O. Mearns, and John T. Abatzoglou. 2022. "The Role of International Resource Sharing Arrangements in Managing Fire in the Face of Climate Change" Fire 5, no. 4: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5040088

APA StyleBloem, S., Cullen, A. C., Mearns, L. O., & Abatzoglou, J. T. (2022). The Role of International Resource Sharing Arrangements in Managing Fire in the Face of Climate Change. Fire, 5(4), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire5040088