Plasma-Polymerized Polystyrene Coatings for Hydrophobic and Thermally Stable Cotton Textiles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. DBD Plasma Generation

2.2. FT-IR Characterization and Analysis

2.3. Hydrophobicity Test Analysis

2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.5. UV Stability of PS-Coated Cotton Textile

3. Results and Discussion

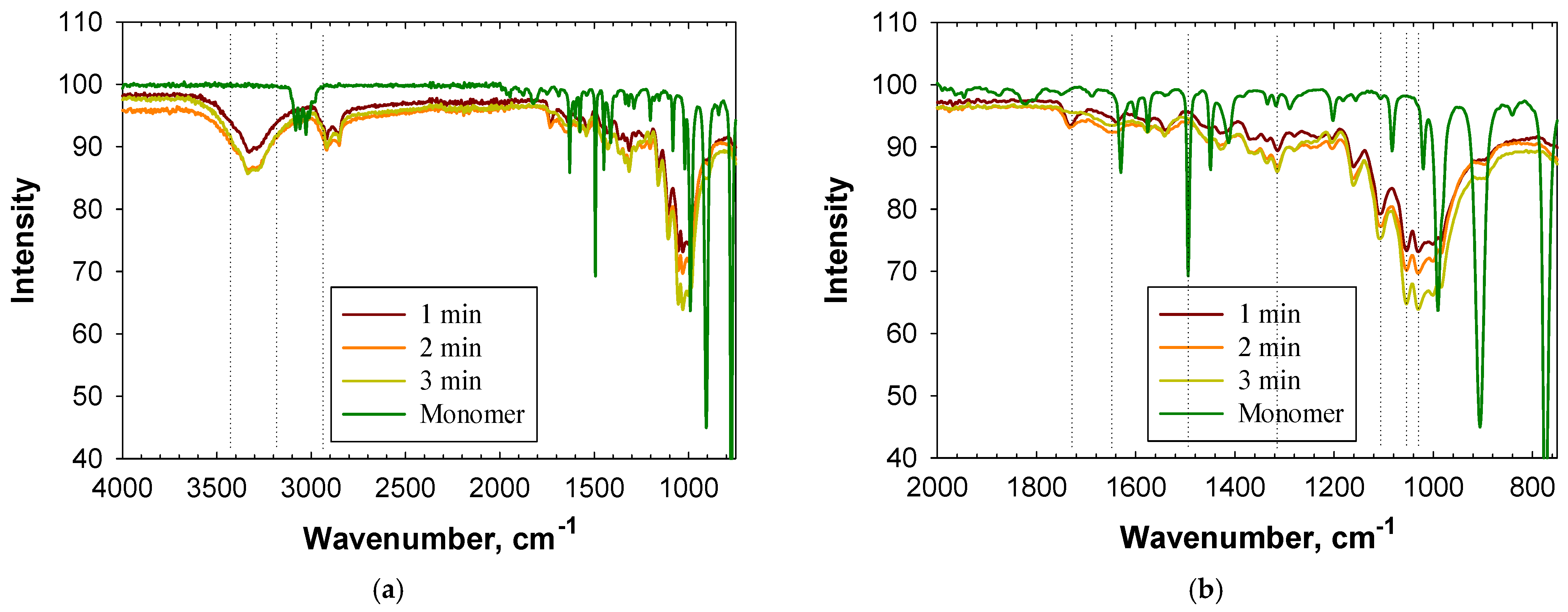

3.1. Characterization of PS Using Infrared Spectroscopy

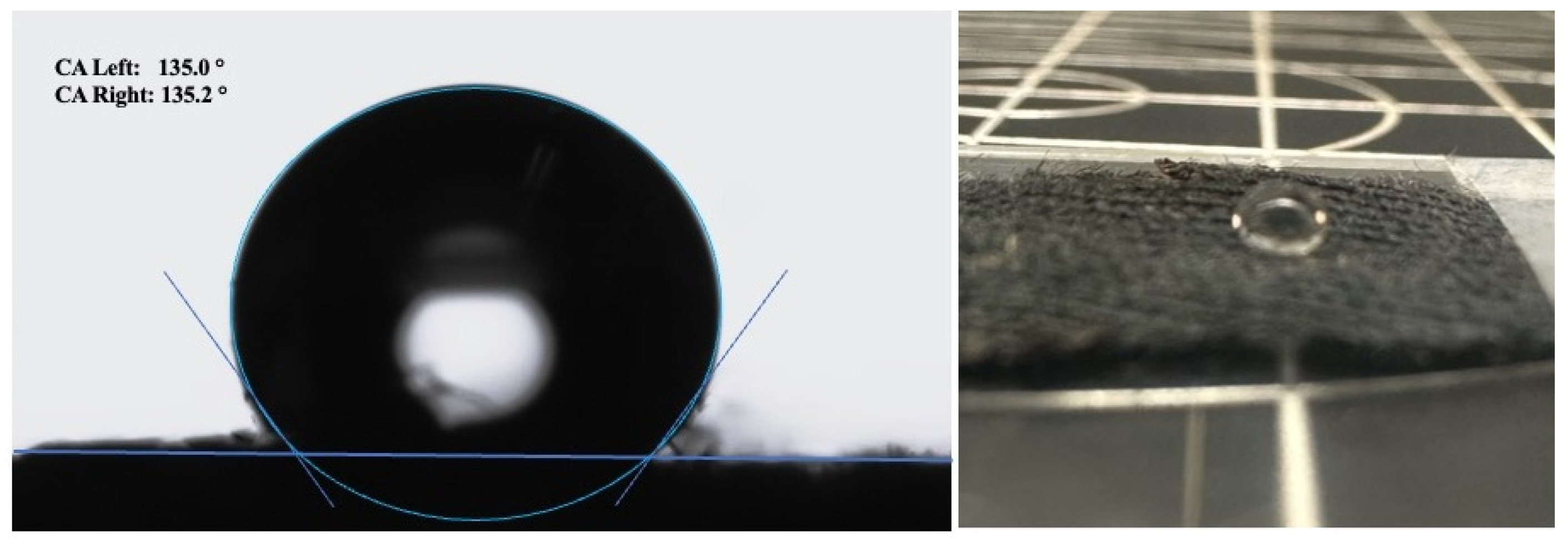

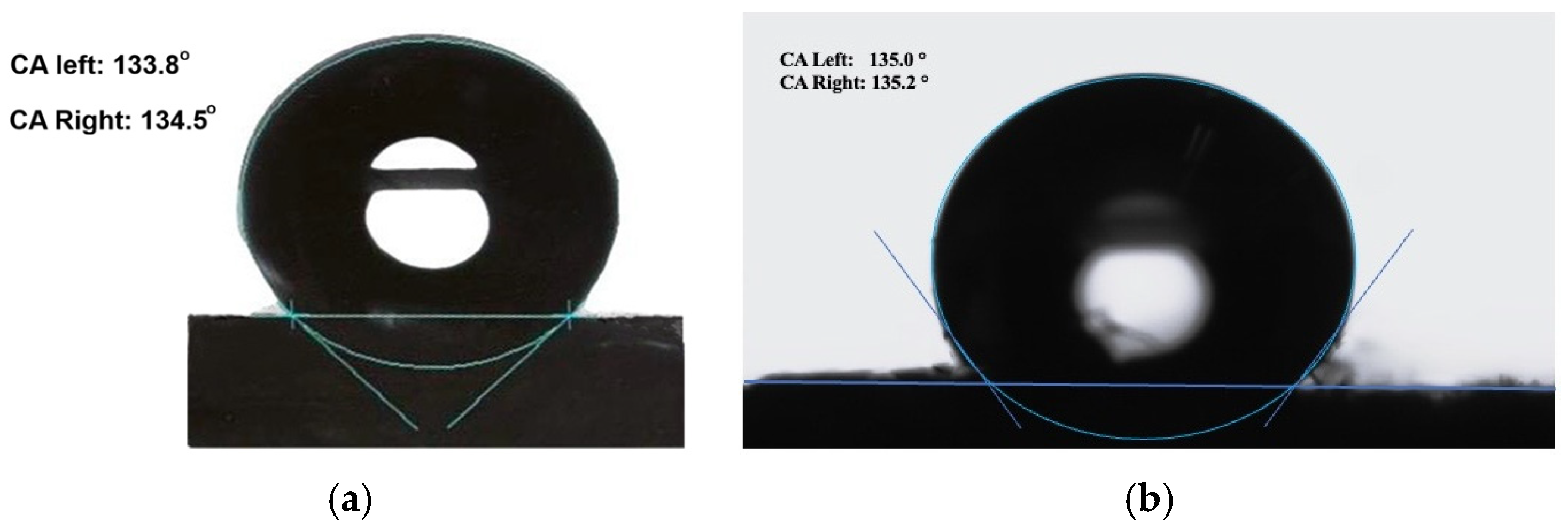

3.2. Hydrophobicity of Cotton Samples After Polymerization

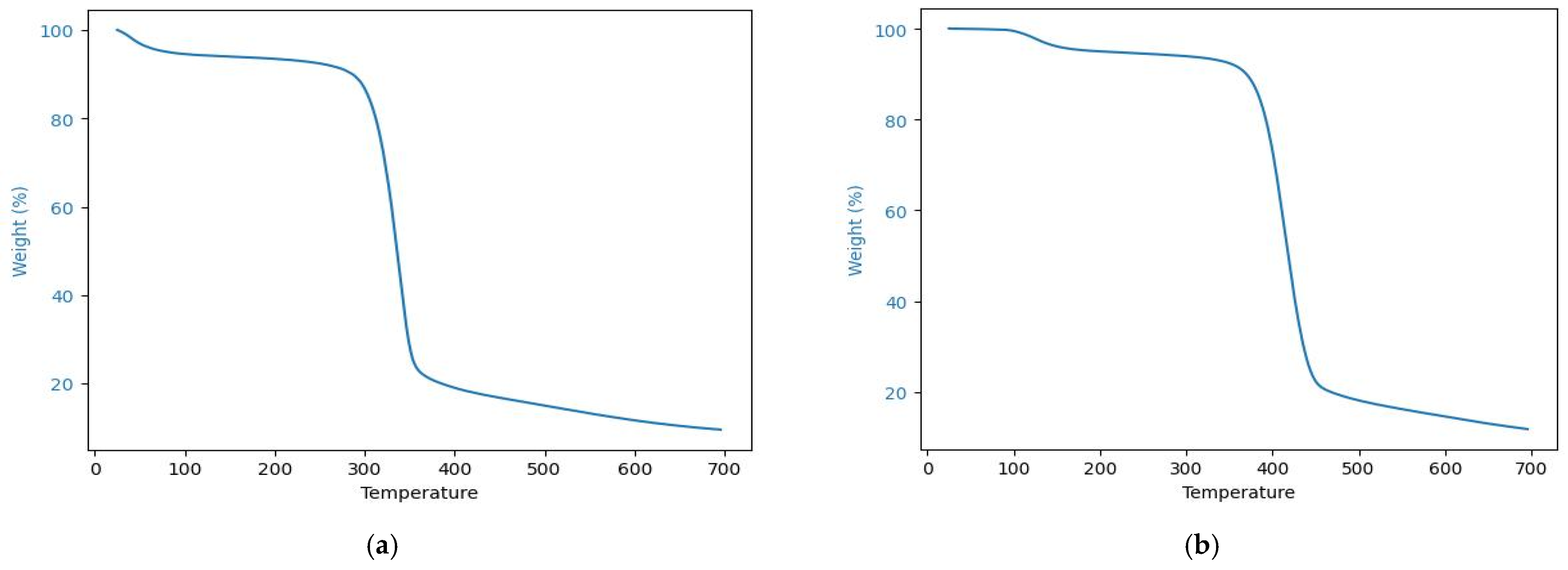

3.3. Thermal Stability of the PS-Modified Textiles

3.4. UV Stability of the PS-Modified Textiles

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kogelschatz, U. Dielectric-Barrier Discharges: Their History, Discharge Physics, and Industrial Applications. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2003, 23, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, J. The Glass Transition Temperature of Polystyrene. J. Therm. Anal. 1996, 46, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kooten, T.G.; Spijker, H.T.; Busscher, H.J. Plasma-Treated Polystyrene Surfaces: Model Surfaces for Studying Cell–Biomaterial Interactions. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 1735–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caicedo-Carvajal, C.E.; Liu, Q.; Remache, Y.; Goy, A.; Suh, K.S. Cancer Tissue Engineering: A Novel 3D Polystyrene Scaffold for In Vitro Isolation and Amplification of Lymphoma Cancer Cells from Heterogeneous Cell Mixtures. J. Tissue Eng. 2011, 2011, 362326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wünsch, J.R. Polystyrene: Synthesis, Production and Applications; iSmithers Rapra Publishing: Shawbury, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-1-85957-191-0. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, K.; Tauer, K.; Yagci, Y.; Moszner, N. Photoinitiated Bulk and Emulsion Polymerization of Styrene—Evidence for Photo-Controlled Radical Polymerization. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 9539–9549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishva, P.; Li, J.; Xie, R.; Tang, J.; Nandy, P.; Farouk, T.; Guo, J.; Peng, Z. Nonthermal hydrogen plasma-enabled ambient, fast lignin hydrogenolysis to valuable chemicals and bio-oils. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 501, 157776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieles, M.; Harper, S.; Ji, H.-F. Bulk Polymerization of Acrylic Acid Using Dielectric-Barrier Discharge Plasma in a Mesoporous Material. Polymers 2023, 15, 2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Cao, M.; Feng, E.; Sohlberg, K.; Ji, H.-F. Polymerization of Solid-State Aminophenol to Polyaniline Derivative Using a Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma. Plasma 2020, 3, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, M.; Merkert, N.; van Duin, A.C.T.; van Duin, D.; Weber, A.P. Advancing DBD Plasma Chemistry: Insights into Reactive Nitrogen Species such as NO2, N2O5, and N2O Optimization and Species Reactivity through Experiments and MD Simulations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 16087–16099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Cao, M.; Qiao, Z.; He, L.; Wei, Y.; Ji, H.-F. Polymerization of Solid-State 2,2′-Bithiophene Thin Film or Doped in Cellulose Paper Using DBD Plasma and Its Applications in Paper-Based Electronics. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 1518–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.M.; Kaushik, N.; Nguyen, T.T.; Choi, E.H.; Nguyen, L.N.; Kaushik, N.K. The Outlook of Flexible DBD-Plasma Devices: Applications in Food Science and Wound Care Solutions. Mater. Today Electron. 2024, 7, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, P.; Van Vrekhem, S.; De Geyter, N.; Morent, R. The Use of DBD Plasma Treatment and Polymerization for the Enhancement of Biomedical UHMWPE. Thin Solid Films 2014, 572, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borra, J.-P.; Valt, A.; Arefi-Khonsari, F.; Tatoulian, M. Atmospheric Pressure Deposition of Thin Functional Coatings: Polymer Surface Patterning by DBD and Post-Discharge Polymerization of Liquid Vinyl Monomer from Surface Radicals. Plasma Process. Polym. 2012, 9, 1104–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morent, R.; De Geyter, N.; Van Vlierberghe, S.; Beaurain, A.; Dubruel, P.; Payen, E. Influence of Operating Parameters on Plasma Polymerization of Acrylic Acid in a Mesh-to-Plate Dielectric Barrier Discharge. Prog. Org. Coat. 2011, 70, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.; Bashir, S. Polymerization of Acrylic Acid Using Atmospheric Pressure DBD Plasma Jet. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 146, 012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri Khoshkar Vandani, S.; Farhadian, L.; Pennycuick, A.; Ji, H.-F. Polymerization of Sodium 4-Styrenesulfonate Inside Filter Paper via Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma. Plasma 2024, 7, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naggar, A.M.; Zohdy, M.H.; Mohammed, S.S.; Alam, E.A. Water Resistance and Surface Morphology of Synthetic Fabrics Covered by Polysiloxane/Acrylate Followed by Electron Beam Irradiation. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2003, 201, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Chauhan, A.; Gaur, R. A Comprehensive Review on the Synthesis, Properties, Environmental Impacts, and Chemiluminescence Applications of Polystyrene (PS). Discov. Chem. 2025, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maafa, I.M. Inhibition of Free Radical Polymerization: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Nagaki, A. Anionic Polymerization Using Flow Microreactors. Molecules 2019, 24, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.K.; Hartman, R.L. Perspectives on Polyolefin Catalysis in Microfluidics for High-Throughput Screening: A Minireview. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieles, M.; Stitt, C.; Ji, H.-F. Bulk Polymerization of PEGDA in Spruce Wood Using a DBD Plasma-Initiated Process to Improve the Flexural Strength of the Wood–Polymer Composite. Plasma 2022, 5, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, M.A.; Gibson, M.I.; Klok, H.-A. Synthesis of Functional Polymers by Post-Polymerization Modification. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Chen, Q.; Fridman, G.; Ji, H.-F. A Colorimetric Method for Comparison of Oxidative Strength of DBD Plasma. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2019, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermán, V.; Takacs, H.; Duclairoir, F.; Renault, O.; Tortai, J.H.; Viala, B. Core Double–Shell Cobalt/Graphene/Polystyrene Magnetic Nanocomposites Synthesized by in Situ Sonochemical Polymerization. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 51371–51381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland-moritz, K.; Siesler, H.W. Infrared Spectroscopy of Polymers. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 1976, 11, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Nakaoki, T.; Ishihara, N. Molecular Conformation in Glasses and Gels of Syndiotactic and Isotactic Polystyrenes. Macromolecules 1990, 23, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jinjin, D. Improvement of Hydrophobic Properties of Silk and Cotton by Hexafluoropropene Plasma Treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 253, 5051–5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhaj Khalifa, I.; Ladhari, N. Hydrophobic Behavior of Cotton Fabric Activated with Air Atmospheric-Pressure Plasma. J. Text. Inst. 2020, 111, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time | Water Contact Angle |

|---|---|

| Without treatment | 0 |

| 1 min | 129.8° |

| 2 min | 133.4° |

| 3 min | 135.1° |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Farhadian, L.; Amiri Khoshkar Vandani, S.; Ji, H.-F. Plasma-Polymerized Polystyrene Coatings for Hydrophobic and Thermally Stable Cotton Textiles. Plasma 2026, 9, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/plasma9010003

Farhadian L, Amiri Khoshkar Vandani S, Ji H-F. Plasma-Polymerized Polystyrene Coatings for Hydrophobic and Thermally Stable Cotton Textiles. Plasma. 2026; 9(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/plasma9010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarhadian, Lian, Samira Amiri Khoshkar Vandani, and Hai-Feng Ji. 2026. "Plasma-Polymerized Polystyrene Coatings for Hydrophobic and Thermally Stable Cotton Textiles" Plasma 9, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/plasma9010003

APA StyleFarhadian, L., Amiri Khoshkar Vandani, S., & Ji, H.-F. (2026). Plasma-Polymerized Polystyrene Coatings for Hydrophobic and Thermally Stable Cotton Textiles. Plasma, 9(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/plasma9010003