Effect of Thermomechanical Loading on the Marginal Precision of Different Lithium-Based Glass-Ceramic Onlay Restorations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

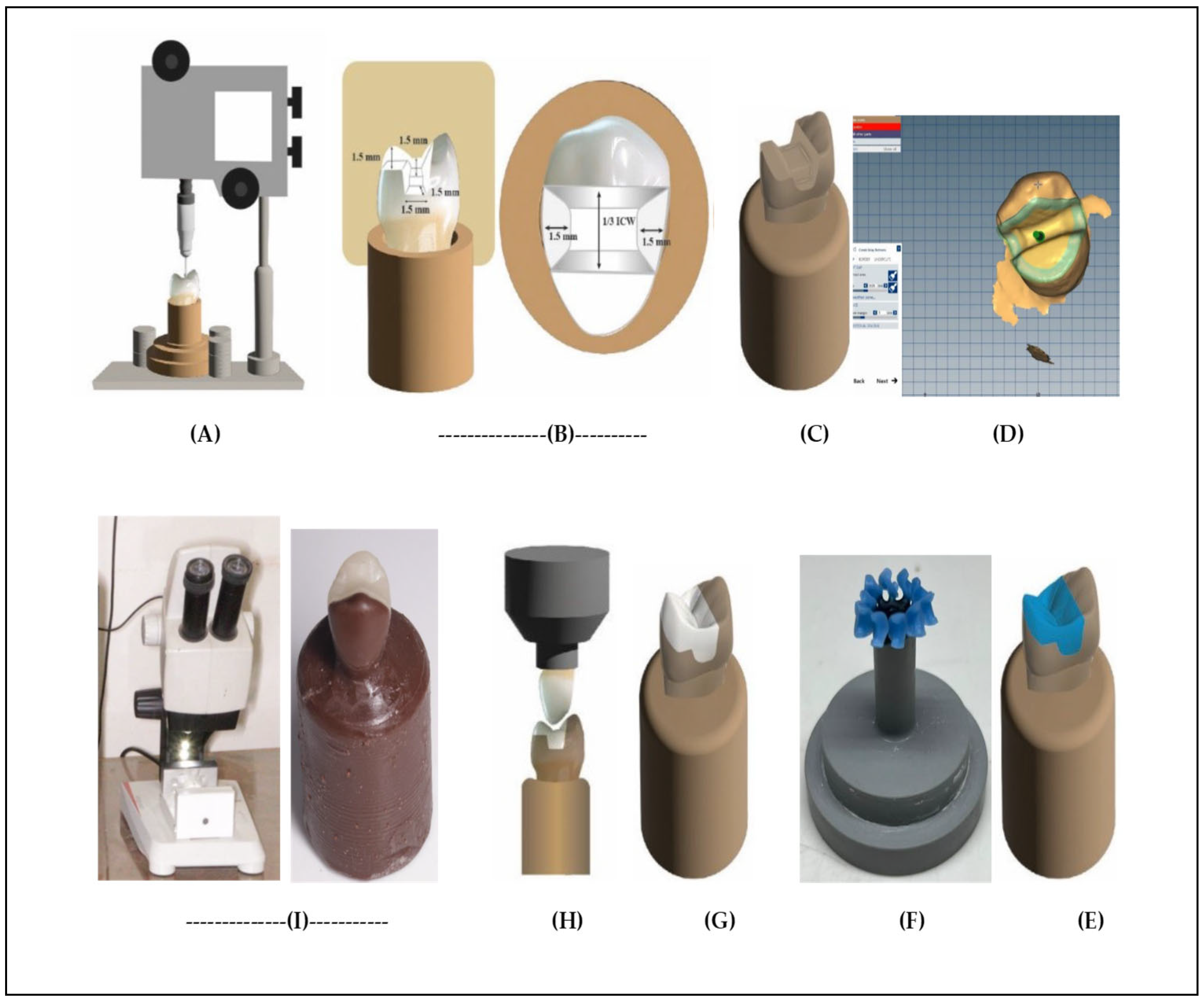

2.1. Master Die Fabrication and Onlay Preparations

2.2. Duplication of the Master Die

2.3. Restoration Construction

2.4. Cementation of Restorations

2.5. Marginal Gap Evaluation

2.6. Thermomechanical Loading

2.7. Statistical Analysis

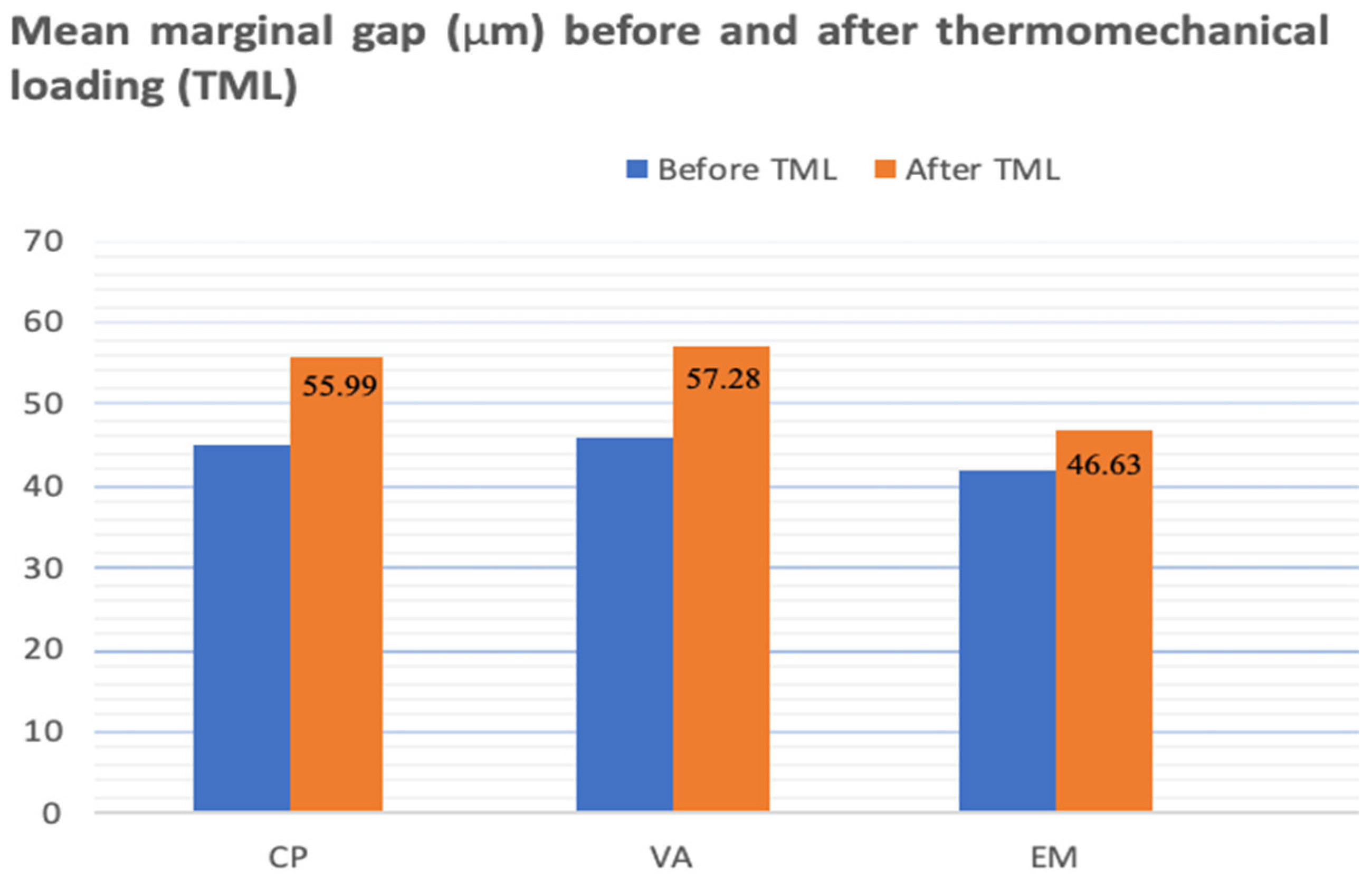

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Present Study

5. Conclusions

- Lithium disilicate (IPS e.max Press) onlay restorations showed more precise marginal fit than two groups of zirconia-reinforced lithium-based ceramic onlays.

- Thermomechanical loading (TML) revealed significant marginal gap values of two zirconia-reinforced lithium-based ceramic onlays compared to lithium disilicate.

- For three lithium-based ceramic onlays, thermomechanical loading (TML) significantly raised the marginal gap; however, the values of this marginal gap fell within the clinically acceptable range.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Edelhoff, D.; Sorensen, J.A. Tooth structure removal associated with various preparation designs for posterior teeth. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2002, 22, 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Monaco, C.; Arena, A.; Štelemėkaitė, J.; Evangelisti, E.; Baldissara, P. In vitro 3D and gravimetric analysis of removed tooth structure for complete and partial preparations. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2019, 63, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffis, E.; Alraheam, I.A.; Boushell, L.; Donovan, T.; Fasbinder, D.; Sulaiman, T.A. Tooth-cusp preservation with lithium disilicate onlay restorations: A fatigue resistance study. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2020, 34, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phark, J.H.; Sillas, D.J. Microstructural considerations for novel lithium disilicate glass ceramics: A review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2022, 34, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliu, R.-D.; Porojan, S.D.; Porojan, L. Vitro study of comparative evaluation of marginal and internal fit between heat-pressed and CAD-CAM monolithic glass-ceramic restorations after thermal aging. Materials 2020, 13, 4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, A. Mechanical and Optical Properties of Machinable and Pressable Glass Ceramic. Ph.D. Thesis, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, N.A.B. Physico-Mechanical Characterisation of a Novel and Commercial CAD/CAM Composite Blocks. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.H.; Lima, E.; Miranda, R.B.; Favero, S.S.; Lohbauer, U.; Cesar, P.F. Dental ceramics: A review of new materials and processing methods. Braz. Oral Res. 2017, 31, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, D.; Wahsh, M. Assessment of marginal adaptation and fracture resistance of endocrown restorations utilizing different machinable blocks subjected to thermomechanical aging. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2018, 30, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaren, E.A.; Figueira, J. Updating classifications of ceramic dental materials: A guide to material selection. Compendium 2015, 36, 739–745. [Google Scholar]

- Alkadi, L.T. IPS e. max CAD and IPS e. max Press: Fracture Mechanics Characterization. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Johani, H. Effects of Etching Duration on the Surface Roughness, Surface Loss, Flexural Strength, and Shear Bond Strength to a Resin Cement of e. max CAD Glass Ceramic. Ph.D. Thesis, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Vardhaman, S.; Rodrigues, C.; Lawn, B. A Critical Review of Dental Lithia-Based Glass–Ceramics. J. Dent. Res. 2023, 102, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracis, S.; Thompson, V.; Ferencz, J.; Silva, N.; Bonfante, E. A new classification system for all-ceramic and ceramic-like restorative materials. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2016, 28, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinke, S.; Pfitzenreuter, T.; Leha, A.; Roediger, M.; Ziebolz, D. Clinical evaluation of chairside-fabricated partial crowns composed of zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate ceramics: 3-year results of a prospective practice-based study. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2020, 32, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, N.; Tostado, G.; Phark, J.; Takanashi, K.; Lin, R.; Duarte, S. CAD/CAM high-strength glass ceramic. Quintessence Dent. Technol. 2015, 38, 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki, F.; Sekine, H.; Honma, S.; Takanashi, T.; Furuya, K.; Yajima, Y.; Yoshinari, M. Translucency and flexural strength of monolithic translucent zirconia and porcelain layered zirconia. Dent. Mater. 2015, 34, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaka, S.E.; Elnaghy, A.M. Mechanical properties of zirconia reinforced lithium silicate glass ceramic. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, M. Effect of different processing techniques on the marginal and internal fit of monolithic lithium disilicate and zirconia-reinforced lithium silicate restorations. Egypt. Dent. J. 2022, 68, 2497–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, H.R.; Rizi, H.B.; Khamseh, M.M.R.; Öchsner, A. Dental restorative materials. In A Review on Dental Materials; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 47–171. [Google Scholar]

- Bahgat, S.F.A.; Basheer, R.R.; Sayed, S.M.E. Effect of zirconia addition to lithium disilicate ceramic on translucency and bond strength using different adhesive strategies. Dent. J. 2015, 61, 4519–4533. [Google Scholar]

- Zahnfabrik, V. VITA AMBRIA® PRESS SOLUTIONS, Technical and Scientific Documentation. 2020. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://mam.vita-zahnfabrik.com/portal/ecms_mdb_download.php%3Fid%3D100097%26sprache%3Den%26fallback%3Den%26cls_session_id%3D%26neuste_version%3D1&ved=2ahUKEwiL27bZ6OSRAxVic_UHHRWaCZQQFnoECBkQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2D3PYeELSn2VG9yA5Ont_H (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Boitelle, P.; Mawussi, B.; Tapie, L.; Fromentin, O. A systematic review of CAD/CAM fit restoration evaluations. J. Oral Rehabil. 2014, 41, 853–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, F.D.; Prado, C.J.; Prudente, M.S.; Carneiro, T.A.; Zancope, K.; Davi, L.R.; Mendonca, G.; Cooper, L.; Soares, C. Micro-computed tomography evaluation of marginal fit of lithium disilicate crowns fabricated by using chairside CAD/CAM systems or the heat-pressing technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 112, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.R.; Gonzalez, M.A.G.; Abu Kasim, N.H.; Abu Kassim, N.L.; Farook, M.S. Effect of operators’ experience and cement space on the marginal fit of an in-office digitally produced monolithic ceramic crown system. Quintessence Int. 2016, 47, 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Stappert, C.F.; Chitmongkolsuk, S.; Silva, N.R.; Att, W.; Strub, J.R. Effect of mouth-motion fatigue and thermal cycling on the marginal accuracy of partial coverage restorations made of various dental materials. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benic, G.I.; Sailer, I.; Zeltner, M.; Gütermann, J.N.; Özcan, M.; Mühlemann, S. Randomized controlled within-subject evaluation of digital and conventional workflows for the fabrication of lithium disilicate single crowns. Part. III: Marginal and internal fit. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haj, N.Ö.H.; Molinero-Mourelle, M.; Joda, T.P. Clinical Performance of Partial and Full-Coverage Fixed Dental Restorations Fabricated from Hybrid Polymer and Ceramic CAD/CAM Materials: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akhali, M.; Chaar, M.S.; Elsayed, A.; Samran, A.; Kern, M. Fracture resistance of ceramic and polymer-based occlusal veneer restorations. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 74, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jlaihawi, Z.G.A.-K. Study of the Physical Properties of a Novel Lithium Aluminosilicate Dental Glass Ceramic; Sheffield Hallam University: Sheffield, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Uttley, J. Power analysis, sample size, and assessment of statistical assumptions-Improving the evidential value of lighting research. Leukos 2019, 15, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminian, A.; Brunton, P.A. A comparison of the depths produced using three different tooth preparation techniques. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003, 89, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.L.; Chang, Y.H.; Liu, P.R. Multi-factorial analysis of a cusp-replacing adhesive premolar restoration: A finite element study. J. Dent. 2008, 36, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujjarlapudi, M.C.; Reddy, S.V.; Madineni, P.K.; Ealla, K.; Nunna, V.N.; Manne, S.D. Comparative evaluation of few physical properties of epoxy resin, resin-modified gypsum and conventional type IV gypsum die materials: An in vitro study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2012, 13, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, M.T.; Yondem, I.; Aykent, F.; Eraslan, O. Influence of the supporting die structures on the fracture strength of all-ceramic materials. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2012, 16, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, R.; Douglas, W.H. An artificial oral environment for testing dental materials. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1991, 38, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawafleh, N.A.; Mack, F.; Evans, J.; Mackay, J.; Hatamleh, M.M. Accuracy and reliability of methods to measure marginal adaptation of crowns and FDPs: A literature review. J. Prosthodont. 2013, 22, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/TR 11405:1994; Dental Materials—Guidance on Testing of Adhesion to Tooth Structure. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994.

- Nawafleh, N.; Hatamleh, M.; Elshiyab, S.; Mack, F. Lithium disilicate restorations fatigue testing parameters: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 25, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boitelle, P.T.; Mawussi, L.; Olivier, B.F. Evaluation of the marginal fit of CAD-CAM zirconia copings: Comparison of 2D and 3D measurement methods. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 119, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alassar, R.M.; Samy, A.M.; Abdel-Rahman, F.M. Effect of cavity design and material type on fracture resistance and failure pattern of molars restored by computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing inlays/onlays. Dent. Res. J. 2021, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homsy, F.R.; Özcan, M.; Khoury, M.; Majzoub, Z.A.K. Comparison of fit accuracy of pressed lithium disilicate inlays fabricated from wax or resin patterns with conventional and CAD-CAM technologies. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 120, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revilla-León, M. Marginal and internal gap of handmade, milled and 3D printed additive manufactured patterns for pressed lithium disilicate onlay restorations. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2018, 26, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mclean, J.W.; von Fraunhofer, J.A. The estimation of cement film thickness by an in vivo technique. Br. Dent. J. 1971, 131, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshvad, A.; Hooshmand, T.; Asefzadeh, F.; Khalilinejad, F.; Alihemmati, M.; van Noort, R. Marginal Gap, Internal Fit, and Fracture Load of Leucite-Reinforced Ceramic Inlays Fabricated by CEREC inLab and Hot-Pressed Techniques. J. Prosthodont. 2011, 20, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, L.; Ulmer, P.; Gerngross, M.D.; Jetter, J.; Mintrone, M.; Lehmann, F.; Kern, M. Properties of hot-pressed lithium silicate glass-ceramics. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitrou, E.A.; Northeast, S.E.; van Noort, R. Brittleness index of machinable dental materials and its relation to the marginal chipping factor. J. Dent. 2007, 35, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, E.; van’t Hoen, C.; Rheinberger, V.; Höland, W. Influence of ZrO2 on the crystallization and properties of lithium disilicate glass-ceramics derived from a multi-component system. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2007, 27, 1571–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Estimation and comparison of Weibull parameters for reliability assessments of Douglas-fir wood. Int. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2014, 14, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Güngör, M.B.; Nemli, S.K. The Effect of Resin Cement Type and Thermomechanical Aging on the Retentive Strength of Custom Zirconia Abutments Bonded to Titanium Inserts. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2018, 33, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElHamid, A.R.; Masoud, G.I.; Younes, A.A. Assessment of fracture resistance, marginal and internal adaptation of endocrown using two different heat–press ceramic materials: An in-vitro study. Tanta Dent. J. 2023, 20, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ceramic Material | Trade Name | Manufacturer (Lot. No) | Chemical Composition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium disilicate glass-ceramic | IPS e.max Press | Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein (Z02HG1) | SiO2 58–80%, Li2O 11–19%, K2Om 0–13%, ZnO2 0–8%, Al2O3 0–5%, P2O5, MgO, and other oxides. |

| Zirconia-reinforced lithium disilicate ceramic | Vita Ambria | VITA Zahnfabrik, Bad Sackingen, Germany (73101) | SiO2 58–66%, Li2O 12–16%, ZrO2 8–12%, Al2O3 1–4%, P2O5 2–6%, K2O 1–4%, B2O3 1–4%, CeO2 0–4%,Tb4O7 1–4%, V2O5 < 1%, Er2O3 < 1%, Pr6 O11 < 1% |

| Zirconia-reinforced lithium disilicate ceramic | Celtra Press | Dentsply, Hanau, Sirona (16004080) | SiO2 58%, Li2O 18.5%, K2O 0–3%, P2O5 5%, Al2O3 1.9%, ZrO2 6–10%, CeO2 2%, Tb4O7 1%, pigments |

| Before TM | After TM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Mean | ±SD | Mean | ±SD | p Value |

| EM | 41.16 C | 5.09 | 46.63 A | 1.76 | 0.002 * |

| VA | 46.41 C | 8.75 | 57.28 B | 3.27 | 0.001 * |

| CP | 45.77 C | 6.35 | 55.99 B | 1.91 | 0.003 * |

| p value | 0.086 | 0.00 * | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Albaqawi, A.H.; Metwally, M.F.; Almohefer, S.A.; Abdelhady, W.A.; Almansour, M.I.; Haggag, K.M.; Sayed, H.M.E.; Bukhary, F.; Madfa, A.A. Effect of Thermomechanical Loading on the Marginal Precision of Different Lithium-Based Glass-Ceramic Onlay Restorations. Ceramics 2026, 9, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics9010003

Albaqawi AH, Metwally MF, Almohefer SA, Abdelhady WA, Almansour MI, Haggag KM, Sayed HME, Bukhary F, Madfa AA. Effect of Thermomechanical Loading on the Marginal Precision of Different Lithium-Based Glass-Ceramic Onlay Restorations. Ceramics. 2026; 9(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics9010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbaqawi, Ahmed H., Mohamed F. Metwally, Sami A. Almohefer, Walid A. Abdelhady, Moazzy I. Almansour, Khaled M. Haggag, Hend M. El Sayed, Ferdous Bukhary, and Ahmed A. Madfa. 2026. "Effect of Thermomechanical Loading on the Marginal Precision of Different Lithium-Based Glass-Ceramic Onlay Restorations" Ceramics 9, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics9010003

APA StyleAlbaqawi, A. H., Metwally, M. F., Almohefer, S. A., Abdelhady, W. A., Almansour, M. I., Haggag, K. M., Sayed, H. M. E., Bukhary, F., & Madfa, A. A. (2026). Effect of Thermomechanical Loading on the Marginal Precision of Different Lithium-Based Glass-Ceramic Onlay Restorations. Ceramics, 9(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics9010003