1. Introduction

Wound care accounts for around 3% of total healthcare costs [

1]. Chronic wounds and wound healing by secondary intention are among the largest contributors to these total costs [

1,

2]. In these wounds, microbial infection is one of the greatest challenges to wound healing [

3]. The microorganisms that colonize wounds usually originate from the patient’s normal flora or can be transmitted through contact with water, fungi or dirty hands of medical staff [

4]. As some of these microorganisms are resistant to antibiotics [

4], new treatment methods can reduce costs and improve patient care [

1,

2].

To date, hydrogels have been described as one of the best forms of dressing for wound healing [

5]. They have a tissue-like structure and biocompatibility, can control fluid loss and release from the body and maintain wettability and moisture in the wound area [

5]. Synthetic nano-sized smectic alumina (LAP), for example, readily forms a hydrogel at a concentration of more than 2% by weight as it behaves thixotropically in water. LAP is a synthetic nanomaterial composed of aluminum oxide (Al

2O

3) particles that are less than 100 nm in size and are organized into a highly ordered, layered (smectic) structure. This specific combination of a high-performance material (alumina) with a controlled nanostructure (smectic/layered) is designed to maximize its surface area and create specific directional properties, which makes it particularly valuable in high-tech fields. In addition, LAP has high biocompatibility, an anisotropic morphology and a large surface area, which enables the improvement of numerous applications in the biomedical field [

6]. These properties allow the use of LAP gel in a variety of non-invasive and/or minimally invasive procedures [

6]. In the cosmeceutical field, it can also be used for dermatological protection and as an ingredient in powders, creams and emulsions [

7]. LAP also offers a controllable platform for delivering therapeutics, while both natural and synthetic clays act as highly effective wound dressings by fighting infection, managing moisture, stopping bleeding, and promoting new tissue growth [

8].

The development of hydrogels that produce oxygen in a controlled manner could provide a unique solution to prevent ischemia-induced death of implanted cells [

8]. Alemdar et al. [

9] prepared oxygen-generating hydrogels by incorporating calcium peroxide (CPO) at different concentrations into gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA). They found that CPO-based oxygen generation reduced hypoxia-induced cell death by limiting necrosis.

In alginate hydrogels with benzoyl peroxide and LAP, a reduction in the proliferation of malignant cells and a concomitant increase in the viability of healthy fibroblast cells was observed [

10].

These results suggest that oxygen-generating hydrogels have the potential to improve tissue engineering strategies aimed at regenerating ischemic tissues [

8]. To our knowledge, CPO has been introduced into LAP hydrogel at various concentrations, and the bactericidal effect has been investigated. We have successfully produced a bactericidal gel that can be used in wound healing.

2. Materials and Methods

Synthetic silicate nanoplatelets (Laponite

® XLG) purchased from Southern Clay Products Inc., Louisville, KY, USA, were used to prepare hydrogel. LAP is a nanosized synthetic smectic silicate nanomaterial. It is characterized by a highly ordered, layered structure composed of aluminum oxide (Al

2O

3) particles with dimensions typically less than 100 nm

2. This smectic organization and anisotropic morphology are specifically designed to maximize surface area and create specific directional properties essential for high-tech biomedical applications. The LAP dispersion was prepared by gradually adding the clay powder to distilled water (9 by weight) with mechanical stirring [

6]. The CPO was added as an oxygen generating agent at different concentrations (0, 5, 10 and 20%

w/

w in LAP) and mixed at room temperature by magnetic stirring to form a homogeneous solution [

9]. The LAP platelets exhibit high hydrophilicity and swelling ability, with a negative surface charge that facilitates strong interfacial interactions with protonated and hydrophilic molecules. The material possesses a specific cation exchange capacity (CEC) of approximately 60 meq/100 g, which dictates its maximum loading capacity for therapeutic agents.

In aqueous environments, LAP behaves thixotropically and readily forms a hydrogel at concentrations exceeding 2% by weight. The resulting three-dimensional network acts as a hybrid interpenetrating matrix that limits the porosity between charged particles, although water diffusion is maintained through the internal pore structure. While the clay itself acts as an effective oxygen barrier, the incorporation of calcium peroxide (CPO) as an additive modulates the hydrogel’s porosity, where an increase in CPO content corresponds to enhanced oxygen release kinetics.

The oxygen release kinetics of LAP-CPO hydrogels were determined using a PreSens optical sensor (detector OXY-1 ST with a needle-like microsensor PSt7) for 6 h and the PreSens Measurement software version v3.1.1 (Studio 2, Germany). The prepared hydrogel samples with a diameter of 5 mm and a thickness of 4 mm were stored in deionized water in a hypoxic environment for 6 h. The optical sensor measured the oxygen concentration once per hour.

The morphology of the hydrogels was examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) with a field emission gun (FEG), Quanta FEG250, with an acceleration voltage of 1 to 30 kV. For this purpose, the hydrogels were freeze-dried for 24 h and coated with gold for 60 s prior to imaging.

The injectability of the hydrogels was tested with the NanoMec50-Hsensor compression tester at a strain rate of 2 mm/min. The prepared hydrogels were filled into a 10 mL syringe with a 0.25 mm diameter needle. This test was performed three times for each sample and the average value was reported.

To perform the antibacterial tests, Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) were cultured in 3% BHI broth (Brain Heart Infusion) at 37 °C for 24 h. The bacterial culture was then diluted in 0.9% saline to 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard.

The inhibitory effect of the hydrogels was tested using the direct contact method [

11]. The bacterial swab was spread in Petri dishes containing Mueller-Hinton medium (spread plate method). Each hydrogel was spread evenly on a glass slide and brought into direct contact with the medium. All tests were performed in triplicate. The agar disk diffusion test was performed by spreading the antimicrobial disks on the agar plate at approximately 0.5 McFarland after application of the bacterial inoculum. The diameters of bacterial growth inhibitions around each disk were measured in millimeters (mm).

Data was collected in five different experiments and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical differences were analyzed by analysis of variance (1-way ANOVA) and Tukey multiple comparison test with Bartlett’s test as post hoc test (p ≤ 0.05) using the program GraphPad Prism© version 6.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software Version 6.00 (San Diego, CA, USA). The populations from the diameters of the inhibition halos were determined with normal distribution and independent of each experiment. The normality of the data was analyzed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. In addition, the correlation between the size of the inhibition halos and the hydrogel concentrations was determined using the Pearson correlation coefficient. All groups were compared with a statistically significant difference at p ≤ 0.0001.

3. Results and Discussion

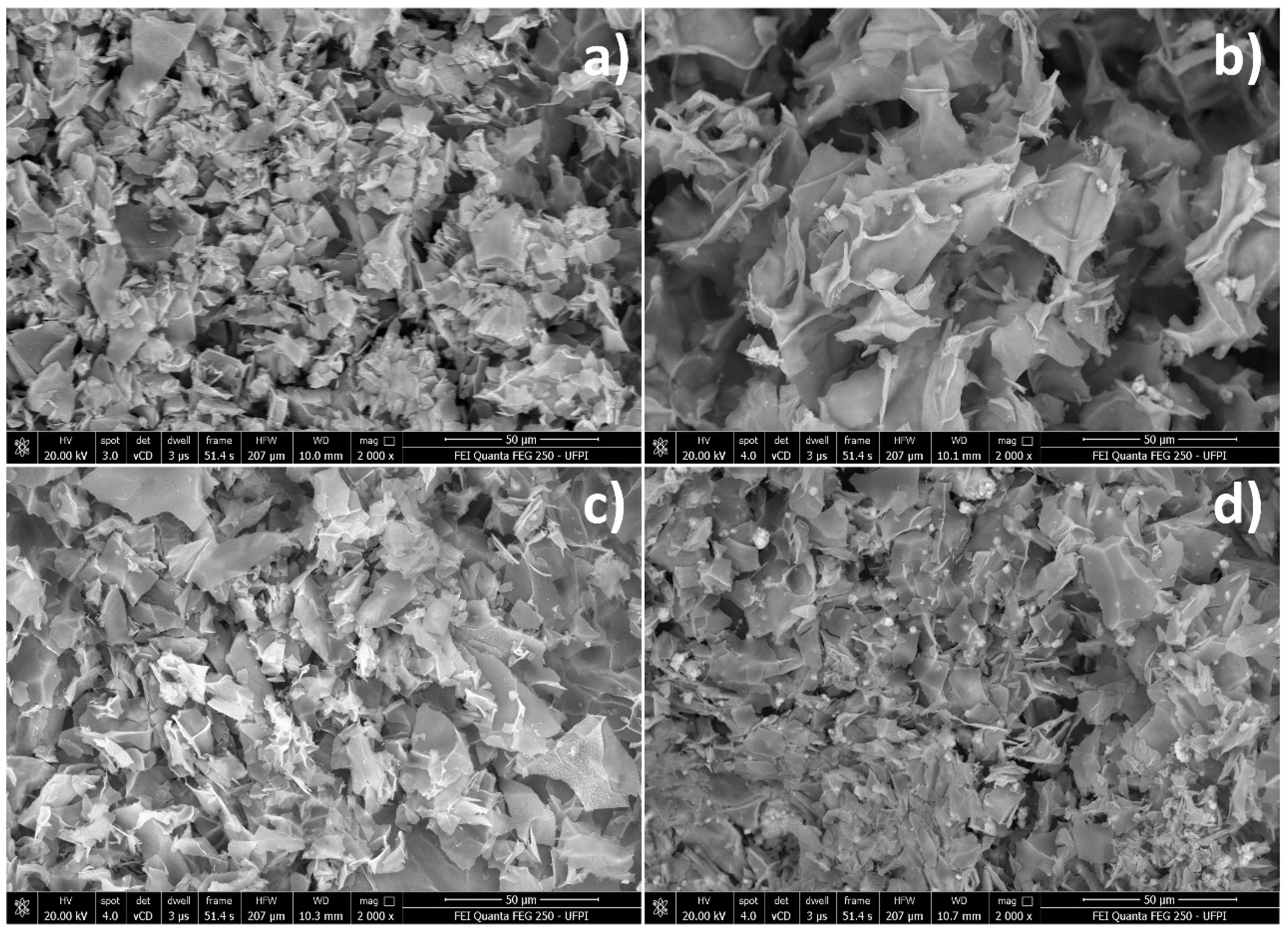

Figure 1 shows the morphologies of lyophilized hydrogels. All samples showed similar lamellar structures, indicating that the LAP platelets were not completely exfoliated. As the CPO content increased, the hydrogels became denser. These results indicate that the LAP do not crosslink in the three-dimensional network structure.

Oxygen release (

Figure 2) was measured under hypoxic conditions and under temperature control (36.5 °C). According to Equation (1), the kinetic release pattern for O

2 was pseudo-first order, with the O

2 fraction inverse to time. The rate increases with n times time for each n concentration, which is due to the increase in CPO with increasing H

2O

2. Moreover, parameters such as temperature and pH are responsible for the formation of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) and O

2 [

12]. Therefore, in the present manuscript, we did not use catalase as a medium to generate the complete reaction from H

2O

2 formed according to Equation (2). But temperature control helped with O

2 formation; however, the result corresponds to low O

2 values.

The “cumulative oxygen release” (

Figure 2a) represents the total oxygen release after the specified time, and the “oxygen release” (

Figure 2b) represents the oxygen release at any time. The point “zero” means that no oxygen was released. The point “100%” represents the total oxygen released. All values measured by the optical sensor were normalized to the percentage of water (11.890%) as a control. After 4 h, LAP-CPO (20.0%) reached its maximum oxygen release, indicating a saturated process and a lower oxygen release rate. However, in LAP-CPO (5.0%), there was a more controllable oxygen release at the first moment, which was prolonged after 5 h and showed 2.47 ± 0.01% oxygen release at this time, LAP-CPO (10.0%) also showed controlled oxygen release but also low percentages of oxygen release and the oxygen release reached the maximum release after 5 h and showed minimum release values of 0.67 ± 0.01 after 5 h.

These results confirm that the increased CPO in the LAP allows controlled oxygen release when the encapsulation efficiency of the LAP is not exceeded. Adover et al. [

14] synthesized gellan gum (GG) with LAP as sustained drug delivery systems. They showed that the presence of LAP enabled a significant slowdown in the release kinetics of hydrophilic drugs, confirming that LAP can be an effective additive for the preparation of sustained delivery systems [

14].

The coefficients of determination (R2) derived from the regression models, 0.84 for LAP-CPO (5%), 0.80 for LAP-CPO (10%), and 0.72 for LAP-CPO (20%), demonstrate a robust linear relationship between time and oxygen release. Specifically, the 5% formulation maintains the highest model fit (R2 = 0.84), confirming that the oxygen release remains highly consistent when the CPO concentration is strictly aligned with the clay’s loading capacity. In contrast, the decrease in R2 values for the 10% and 20% groups reflects the lower encapsulation efficiency and reduced control that occurs once this mineralogic saturation limit is exceeded. These high correlation values emphasize that the LAP-CPO system provides a more predictable platform for sustained therapeutic delivery than the exponential release often observed in degradable organic hydrogels.

Porion et al. [

15] showed that clay is used to determine the mobility of water molecules and water diffusion. Their results confirm that there is water diffusion due to the porosity present. However, the LAP acts as a matrix for the charged particles and limits the porosity between the particles. Furthermore, the addition of CPO contributes to the porosity of the hydrogels, and the more CPO present in the hydrogels, the higher the oxygen release [

9].

In another study, Montesdeoca et al. [

13] synthesized CPO-loaded GelMA hydrogels at a concentration of 0.5, 1 and 3%

w/

w. Their results show that 3% allows a higher oxygen release for up to 6 days. Therefore, LAP as a hydrogel matrix forms a hybrid interpenetrating network, but in the presence of other additives, added nanoparticles can be released through the pores. Tritschler et al. [

16] used LAP as a polymer for the oxygen barrier. As a result, they showed that LAP acts efficiently as a barrier. The release time depends directly on the LAP content in the formulation (concentration) [

17].

The present results were compared with a previous manuscript [

13] in which two variables for oxygen release (time and CPO concentration) were considered. The oxygen release previously reported with GelMA-CPO hydrogels was 9.83 ± 0.30%, 10.09 ± 0.30% and 52.33 ± 1.57% on the first day [

13]. A decrease was observed on the remaining days. The overall analysis comparing the results presented here (

Figure 2) with those previously reported [

13] is shown in

Figure 2c,d. The oxygen release of GelMA hydrogels remains constant at lower concentrations of CPO and decreases at higher concentrations (3%).

These variations between biomaterials were expected due to the different diffusion coefficients for LAP and polymers. When polyether ether ketone (PEEK), polylactide (PLA) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) are exposed to temperature, the liquid can permeate through the porosity, increasing the release due to the chemical and physical properties as well as the degradation process of the polymers. The same is true for GelMA; degradation begins when water penetrates through the porosity and allows a chemical reaction and oxygen release, resulting in an exponential release [

18].

On the other hand, LAP is a clay that can act as a gel without being affected by temperature and hydrophilic properties, concentration and drug concentration. The LAP hydrogel exhibits superior structural stability compared to traditional organic polymers like GelMA, primarily because its mineralogic properties allow it to maintain gel integrity regardless of temperature variations. Unlike polymers that undergo rapid degradation as water penetrates their pores, LAP is a synthetic smectic clay that acts as a stable matrix and an effective oxygen barrier, providing a more controllable and sustained delivery profile. While the physical structure remains robust, the experimental success of the hydrogel is still heavily dependent on the concentration of additives; specifically, the oxygen release kinetics are governed by the clay’s loading capacity. When the calcium peroxide (CPO) content stays within the material’s specific cation exchange capacity of approximately 60 meq/100 g, as seen in the 5% concentration, it achieves a superior sustained release. However, exceeding this limit (as observed in 10% and 20% formulations) reduces encapsulation efficiency and results in lower final oxygen release values. Thus, while LAP is largely unaffected by temperature-induced degradation, its performance is still precisely modulated by the chemical saturation limits of the clay matrix. Therefore, the diffusion coefficient increases with time and provides a better profile for sustained drug release. This is due to the properties of LAP, such as high hydrophilicity, swelling ability and cation exchange capacity, whereby protonated and hydrophilic drug molecules show a strong interfacial interaction with the negative surface of LAP [

19].

In addition, the presence of LAP clay contributes to reducing the degradation rate of other materials that allow complete release of oxygen, such as nanocomposites with a high clay mineral content (80:20), where the degradation rate decreased by 5.5% after 48 h. There was also a decrease in mass loss from 47 to 23 for LAP/poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) with a 40% to 70% LAP clay content over a 21-day period. It is also important to note that a high LAP content would result in a highly cross-linked film network as the biomaterial becomes more resistant [

19,

20].

However, both CPO concentration and drug concentration affect the encapsulation efficiency (EE). The LAP is a major factor because when the drug concentration exceeds the maximum loading capacity (about 60 meq/100 g, which means that 100 g LAP can hold up to 1.38 g Na (Na molecular weight 23 g mol)), the EE is reduced. This is the reason why at 10% (

w/

w) and 20% (

w/

w) CPO in LAP, oxygen release decreased and was complete at 10% CPO (0.67 ± 0.01)% after 5 h and at 20 CPO (0.75 ± 0.01)% after 2 h. Compared to 5% CPO, oxygen release was better controlled as it was still incomplete after 5 h (2.47 ± 0.01)%,

Figure 2c [

19,

21].

Therefore, the global linear fit for both hydrogels loaded with CPO nanoparticles shows that there is a statistically significant relationship for all samples: LAP-CPO (5%, 10% and 20%) show

p-values (0.01, 0.01 and 0.02, respectively), as shown in

Figure 2d. There is also a perfect negative correlation decreasing linearly between time and oxygen release for both hydrogels compared; previous reports showed similar results.

The controlled release of oxygen from the LAP-CPO hydrogels is intrinsically linked to the mineralogic and physicochemical properties of synthetic clay. As a nanosized synthetic smectic silicate, LAP provides a high surface area and an anisotropic morphology that serves as a robust platform for the delivery of therapeutics. While the LAP clay matrix is known to limit porosity between particles, the incorporation of CPO as an additive introduces additional porosity into the hydrogel structure. This mineralogic arrangement allows for water diffusion, which is essential for the chemical reaction of CPO that generates oxygen. The sustained release profile is governed by the LAP’s loading capacity. When the CPO concentration exceeds this maximum, as observed in the 10% and 20% (w/w) formulations, the encapsulation efficiency decreases, leading to lower final oxygen release values compared to the 5% formulation. Unlike organic polymers such as GelMA, which undergo rapid degradation as water penetrates their pores, LAP maintains a stable gel structure that is less sensitive to temperature variations and hydrophilic degradation. The layered smectic structure of LAP acts as an effective oxygen barrier, slowing down release kinetics and providing a more controllable, sustained delivery profile.

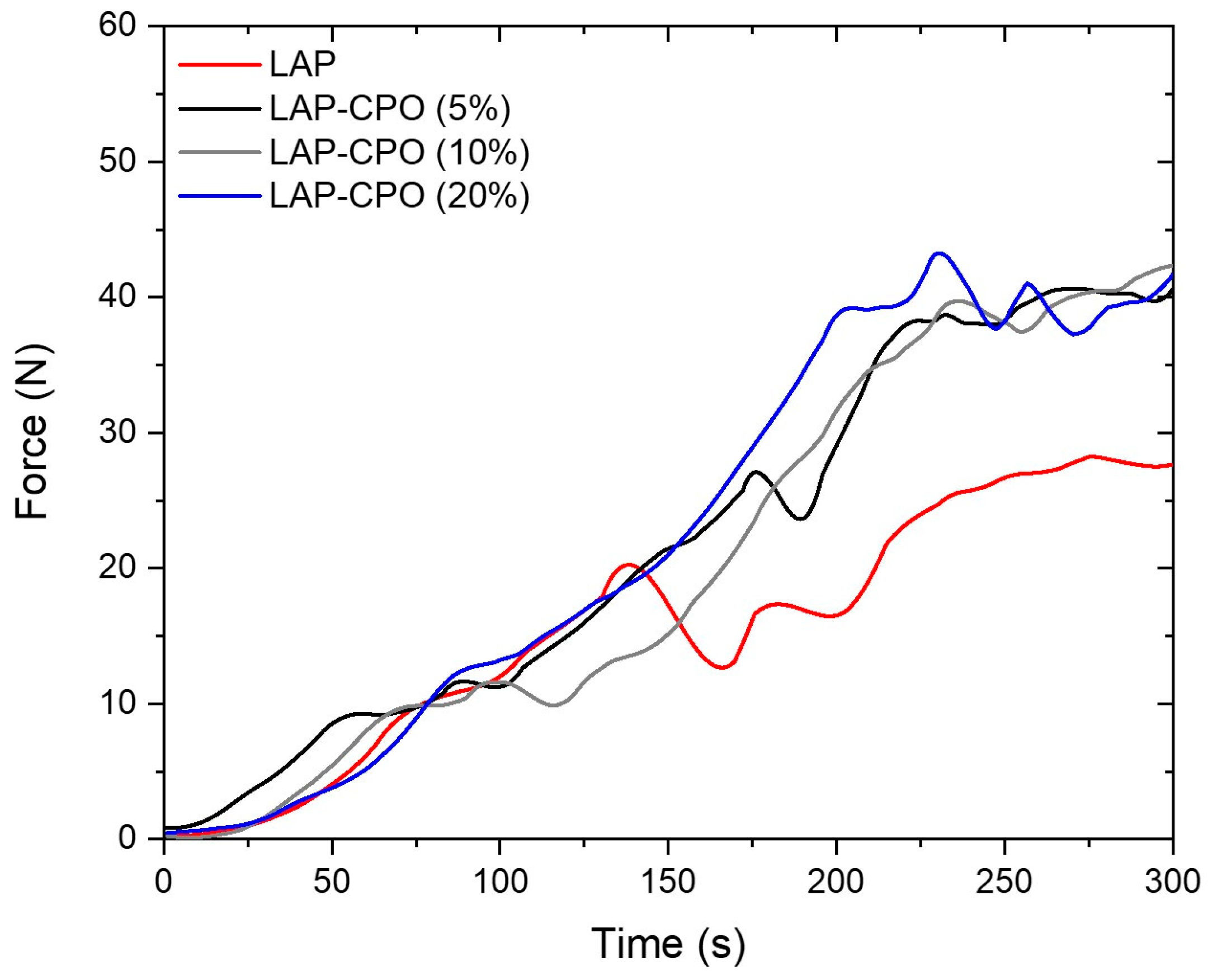

The injectability tests (

Figure 3) examined how well the hydrogel flows through the needle and syringe. This can play a crucial role in evaluating the performance and suitability of hydrogels for different applications. The viscosity of all hydrogels produced increased over time. This behavior occurs until an equilibrium state is reached, and the hydrogels behave like Newtonian molecules, with constant viscosity [

22]. The presence of CPO reduced the LAP lamellae (as seen in

Figure 1).

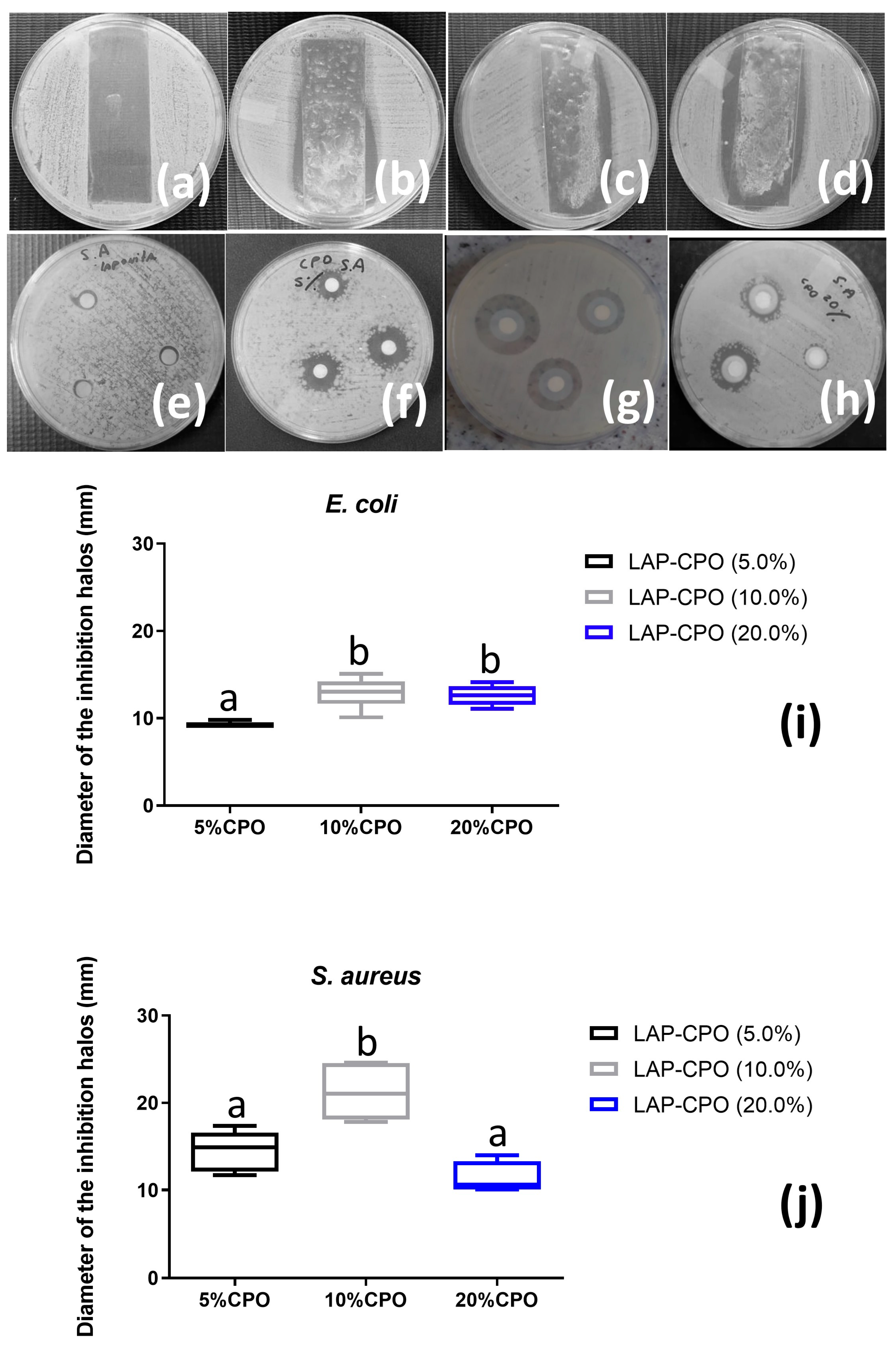

The colony count is used to analyze the extent to which the material inhibits or slows down the growth of pathogenic bacteria. The formation of inhibition zones was observed in all LAP-CPO hydrogels (

Figure 4a–d). Vishnuvarthanan and Rajeswari (2019) [

23] also showed that the addition of LAP significantly improved the antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative microorganisms and increased the antibacterial barrier properties. The hydrogel dressing has thermal insulators that create a powerful antimicrobial environment that is impermeable to wound pathogens and further protects the wound from external contamination [

24].

Akhavan-Kharazian and Izadi-Vasafi investigated the effect of CPO in polymer films based on chitosan and gelatin [

25]. They also showed that the antibacterial activity of the films against

E. coli increased with the addition of CPO to the film composition. Oxygen release peaked on the first day and gradually approached a constant value over the following 7 days [

25].

The diffusion test with LAP as a control (

Figure 4e,f) was performed to ensure that the antibacterial activity of the hydrogel was not affected by LAP. The diameters of the inhibition zones of bacterial growth around each disk (

Figure 4i,j) are related to the sensitivity of the bacterial sample and the diffusion rate of the antimicrobial agent in the agar [

26]. The highest average values for the size of the inhibition zones produced by the hydrogels were obtained at concentrations of 5% and 10% (for

S. aureus). However, at the highest CaO

2 concentration, a reduction in halos was observed (

Figure 4f). It is likely that the disks absorbed CaO

2, making it difficult for it to be released into the medium [

27,

28].

This result indicates that possibly the outer membrane was lysed by ROS, which caused damage that could lyse the microorganism. The most potent radical inducing cell damage is O

2, which is present in almost all aerobic cells and is the reaction of a reducing agent [

29]. In addition, LAP may have the ability to adsorb and fix microorganisms, resulting in enhanced antimicrobial activity [

30]. This activity is attributed to its structure and antimicrobial mode of action as well as the difference in the cell wall structure of the indicator microorganisms [

23]. The result of antibacterial activity in summary form, possibly due to ROS-induced damage to the bacterial membrane, leading to destabilization of its integrity causing ion influx and bacterial death [

31]. Increased calcium accumulation (Ca

2+) in the cytoplasm leads to activation of the mitochondrial electron transport chain and generation of ROS. Mitochondrial production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and water results in low oxygen concentrations that lead to the early stages of ROS production [

31].

As a structural component of LAP, lithium (Li+) plays a crucial role in maintaining the synthetic clays highly ordered, layered (smectic) structure, which directly facilitates its controlled oxygen generation and antimicrobial capabilities. This mineralogic stability allows LAP to form a thixotropic gel that remains physically robust regardless of temperature variations or hydrophilic degradation, unlike organic polymers that release oxygen exponentially as they break down. The Li+-stabilized framework dictates a specific cation exchange capacity, which acts as a regulatory “loading capacity” for therapeutic agents like CPO. When CPO is maintained within this limit, as seen in the 5% formulation, the LAP matrix serves as an effective oxygen barrier that modulates porosity, providing a superior and sustained oxygen release profile (e.g., 2.47 ± 0.01% after 5 h). Furthermore, the inherent ionic structure of the clay enhances antimicrobial activity by providing thermal insulation and the ability to physically adsorb and fix microorganisms. This structural effect works synergistically with the ROS generated by CPO to lyse bacterial membranes, creating a powerful, impermeable barrier against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens.