1. Introduction

Robotic exoskeletons are wearable robotic devices that help people move, walk, or recover after injury [

1,

2]. They can be used in rehabilitation for patients with stroke or spinal cord injury, and they are also being explored in areas such as elderly care, industry, and even military applications. What makes them important is their ability to give support and restore mobility where the human body alone cannot.

For an exoskeleton to work correctly, it must be able to detect and classify the user’s intended locomotor action in real time. Everyday actions like sitting, standing, walking, or climbing stairs are simple for humans but, for a robot, recognizing these activities in real time is a challenge. This is why Human Activity Recognition (HAR) systems are so important [

3]. HAR uses sensors—such as electromyography (EMG), inertial measurement units (IMUs), or pressure sensors—to capture signals from the body. With the help of machine learning and deep learning, these signals can be classified into different activities, allowing the exoskeleton to move in sync with the user.

One of the important parts of lower limb exoskeletons is the data acquisition system (DAQ); its role is to track user motions easily and to provide efficient device control. The main challenges of DAQ are sensor integration, data processing, and hardware implementation. To reach a strong maximum integration and dependability, the design usually revolves around an industrial computer, with a CAN bus controller enabling communication between various hardware components, such as drivers and sensors [

4].

Several techniques are adopted in the hardware implementation of data acquisition circuits to improve the functionality and efficiency of lower limb soft exoskeletons. A multi-channel signal acquisition system built on the CAN bus is another technique. This technique focused on torque signal acquisition, which is essential for intention recognition. With its robust anti-interference characteristics and high acquisition accuracy, this system—which utilizes the ACK-055-10 driver for A/D conversions—is dependable for real-time applications [

5].

Giorgos et al. presented a modular sensor-based system that overcomes the drawbacks of existing laboratory-constrained techniques, which improves biomechanical assessment and control in lower limb exoskeletons. The proposed system incorporated enhanced sensor technologies into 3D-printed insoles and instrumented crutches, such as load cells, force-sensitive resistors, and IMUs, to collect thorough biomechanical data. The system can accurately measure biomechanical parameters and recognize gait phases by utilizing fuzzy logic techniques for exoskeleton control and real-time gait phase estimation. To validate the system’s capability and to provide precise gait analysis, three-person validation tests were performed that compare the system to industry-leading motion capture and force plate technologies [

6]. The main limitations of this technique are that it is restricted to lab environments, and the control systems are expensive and complicated.

Another strategy was a wearable device with an STM32F103C8T6 core that uses flexible film plantar pressure sensors and inertial attitude sensors to combine motion and pressure data, making full detection of intention easier [

7]. This design was mainly based on providing a wearable lower limb motion data acquisition system to safeguard the health of the elderly.

A lightweight exoskeleton with joint-embedded goniometers and IMUs was presented by Haque et al. [

8]. The system was tested against optical motion capture systems, showing excellent accuracy in measuring joint angles. To overcome the shortcomings of conventional marker-based systems in practical situations, the study focused on a lightweight exoskeleton-based gait data collection system with joint-embedded goniometers and inertia measurement units (IMUs) for precise lower limb movement measurements. The main limitations are that it is based on markers that were only applicable in lab settings and data collection in real-world situations is challenging.

IMUs were used in [

9] to gather motion data in real time, and Kalman filtering was utilized to improve data accuracy. This allows exoskeletons to enable precise motion control. The authors of this work concentrated on utilizing IMUs to collect real-time motion data from the lower limbs of humans by using Kalman filtering to improve precision. It did not, however, particularly include the hardware implementation of data-collecting units for exoskeletons used in the lower limbs.

Wujing Cao et al. provided a scalable hardware circuit system for a soft lower limb exoskeleton. This design was intended to increase walking efficiency by force tracking capabilities and sensor data collection. With a 7.8% decrease in net metabolic costs and a 1%-time error in peak assistance force, this technology proved to be useful in practical settings [

10].

Another article proposes a two-channel EMG signal measurement system for human lower limb activity recognition [

11]. The recorded EMG dataset is classified by denoising the raw EMG signal using a hybrid wavelet decomposition with ensemble empirical mode decomposition (WD-EEMD) approach. This research validates the efficiency of the two-channel data-collecting device for measuring EMG signals from lower limb muscles through five leg exercises. Enhancing the identification of human lower limb activity in exoskeleton applications requires this hardware implementation.

A. Zhu et al. introduced a wearable lower limb exoskeleton data acquisition system that makes use of dispersed data collection nodes on the soles of the feet, thighs, and shanks. These nodes were connected by CAN buses, which enable effective data collection, storage, and presentation via Wi-Fi, improving sensor mobility and expansion. Motion range restriction from wired transmission and function loads on the primary data collection node were the design’s primary drawbacks [

12].

To improve rehabilitation exoskeletons through long-term gait observation and load collective calculations, David et al. proposed an affordable data acquisition system for lower limb biomechanical measurements that utilized off-the-shelf components and a Cloud Server for centralized data storage, a wearable biomechanical data acquisition device that runs on the cloud to gather biomechanical measures of the lower limbs in daily living [

13].

Furthermore, a multichannel information acquisition system based on an FPGA and USB 2.0 interface provides high performance and low power consumption, supporting synchronous data acquisition and real-time processing [

14]. The paper discusses a multichannel information acquisition system designed for human lower limb motion, which can be applied to lower limb soft exoskeletons. It utilizes FPGA technology, a USB 2.0 interface, and LabVIEW for high-performance, low-power consumption data acquisition. The system enables synchronous information acquisition and processing, along with real-time data display and storage, making it suitable for analyzing and processing data related to lower limb movements, essential for exoskeleton rehabilitation applications.

In [

15], G.J Rani et. al. introduced a study for using sEMG signals from the leg muscles of people with both healthy and damaged knees to examine the use of multiple deep learning models and the effect of window size for lower limb activity detection. Eleven people in all, including those with and without knee issues, engaged in three different activities: sitting, standing, and walking. The raw signal was preprocessed by applying a band pass filter and Kalman filter. The resulting signals were segmented into multiple window widths and then applied to different deep learning techniques to predict lower limb activity. They performed three different scenarios: individuals in good health, individuals with knee issues, and pooled data. The results showed that the CNN +LSTM hybrid technique reached an accuracy of 98.89% for pooled data, 98.78% for healthy participants, and 97.90% for subjects with knee abnormalities.

In another study [

16], the authors presented a deep learning ensemble (DL-Ens) technique. It was composed of three lightweight convolutional and recurrent neural networks to increase the accuracy of the HAR system. Both the publicly available UCI’s human activity recognition (UCI-HAR) dataset and a self-recorded dataset obtained using numerous wearable motion sensors were used to evaluate the activity detection performance of the proposed DL-Ens technique. The results showed that, on the self-recorded dataset, the suggested DL-Ens method obtains a classification accuracy of 97.48 ± 5.02%, while, on the UCI-HAR dataset, it reaches 93.36 ± 5.89%.

S. Mekruksavanich et.al. [

17] provided a unique hybrid deep learning architecture known as CNN-LSTM to improve the accuracy of identifying human lower limb movement. The HuGaDB dataset was used for this work. This dataset is made up of information gathered from a body sensor network that includes six wearable inertial sensors, such as gyroscopes and accelerometers. These sensors were placed on the shins, feet, and thighs on the left and right sides. The investigation’s findings showed that the recommended model attained a remarkable precision of 97.81%. The results demonstrate the efficacy of the CNN-LSTM model in accurately identifying human lower limb movement.

Recent studies have explored advanced sensor modalities and spatial encoding techniques for lower limb motion understanding. Lian et al. [

18] introduced a flexible sensor array that transforms multi-point deformation signals into a Relative Position Image, enabling deep-learning-based recognition of lower limb movements. This approach demonstrates how spatial sensing and image-like representations can enhance motion recognition and support early intention detection.

However, another study presented by Obukhov et al. [

19] can be considered a complete system for recognizing and classifying motor activity through the sensor fusion of IMU and EMG sensors in addition to virtual reality (VR) trackers. This system was developed for upper limb exoskeletons where CNN GRU networks and transformers have been used for activity classification. The experimental work showed that all proposed models perform accurately in classifying motor activities. When all sensor signals are used together, the transformer achieves the best performance with an accuracy of 99.2%, while the fully connected neural network follows closely at 98.4%. Interestingly, when the classification relies only on IMU data, the fully connected neural network, transformer, and CNN–GRU models all reach 100% accuracy. These results highlight two key points: first, the effectiveness of the proposed deep learning architectures for motor activity recognition and, second, the advantage of a multi-sensor approach, which helps overcome the inherent limitations of individual sensors and improves overall robustness and reliability of the classification system.

Previous studies highlighted the need for reliable sensing and robust signal processing pipelines to improve locomotor activity recognition for wearable assistive devices like exoskeletons. However, most existing datasets are limited in size, constrained to laboratory conditions, do not combine both sEMG and IMU measurements, or do not provide synchronized multimodal data with publicly available benchmarks. Moreover, while individual components of this pipeline have been reported separately in the literature, their integration and validation on a new experimental dataset provides new empirical insights and has been rarely presented.

This work provides new experimental evidence through the acquisition and public release of the SDALLE dataset and its systematic evaluation using a unified preprocessing and deep-learning-based classification pipeline. Hence, this motivates the development of our experimental SDALLE DAQ system, which integrates multi-muscle sEMG signals with 6-DOF IMU measurements collected from multiple human subjects. To enhance the reliability of activity recognition, the raw signals require preprocessing steps such as augmentation and denoising to improve generalization and reduce noise inherent in wearable sensors. After preparing the dataset, a temporal convolutional neural network (TCNN) is adopted to automatically learn discriminative temporal features for classifying common locomotor activities relevant to exoskeleton control. Further work has been to compare the applied TCNN deep learning technique with supervised machine learning classifier like Random Forest to validate the achieved results. Further validation has been achieved by implementing our methodology of data preprocessing and deep learning classification on an open-source dataset. Finally, the results obtained have been compared to other benchmark DAQ systems showing their consistent classification accuracy.

The methodology of this work is presented in

Section 2, where the experimental work, data preprocessing, and the utilized signal conditioning techniques are presented. The classification using deep learning technique and the obtained classification results in addition to their discussion are presented in

Section 3. This paper is finalized with the conclusion and future work in

Section 4.

2. Methodology

It is possible to collect information from lower limb movements using various wearable sensor modalities, including EMG and IMU sensors. EMG sensors are useful because they capture the onset of muscle activation, allowing early detection of movement intent. IMU sensors, on the other hand, provide high-resolution measurements of segment orientation and acceleration, making them more effective for identifying the kinematic patterns associated with different locomotor activities.

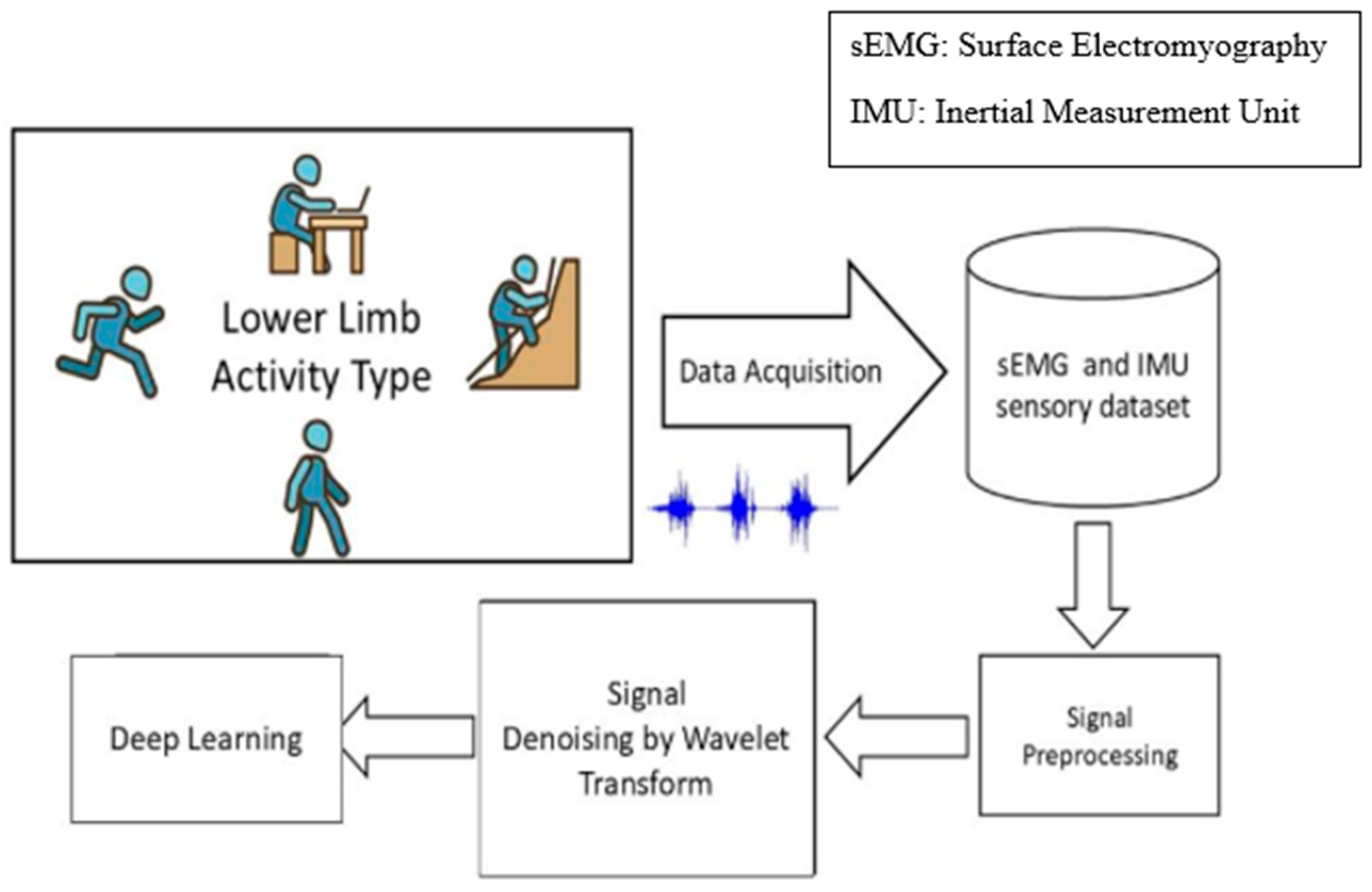

Figure 1 shows the proposed workflow for the classification of lower limb activities of EMG and IMU signals. To create a collective database for all the various activities, including jogging, walking, and utilizing the stairs, the collected dataset of EMG and IMU signals is compiled. In a k-fold cross-validation approach, the entire EMG dataset is then separated into training and test sets, meaning that one subset is kept for testing purposes in each iteration. Unlike the proposed work in [

20], we introduce deep learning for the HAR system.

2.1. Data Acquisition

Unlike studies that rely on simulated data or reused benchmarks, a new dataset is experimentally collected using our custom wearable system and provides original sensory recordings for lower limb locomotion. This sensory data has been assembled and published as a new dataset for activity recognition named “SDALLE-Dataset” [

21]. This dataset is developed specifically for this study and is experimentally collected from 9 healthy subjects. The biomechanics of these subjects are shown in

Table 1, where the statistical range (average ± standard deviation) for age, weight, and height is calculated.

SDALLE DAQ system is used for data collection with the inclusion of sEMGs and IMU sensors. Data has been extracted from the following muscles:

Rectus Femoris, Vastus Medialis, Vastus Lateralis, and Semitendinosus muscles on both the left and right sides. These muscles have been selected as the most effective during gait recognition in several previous studies [

20,

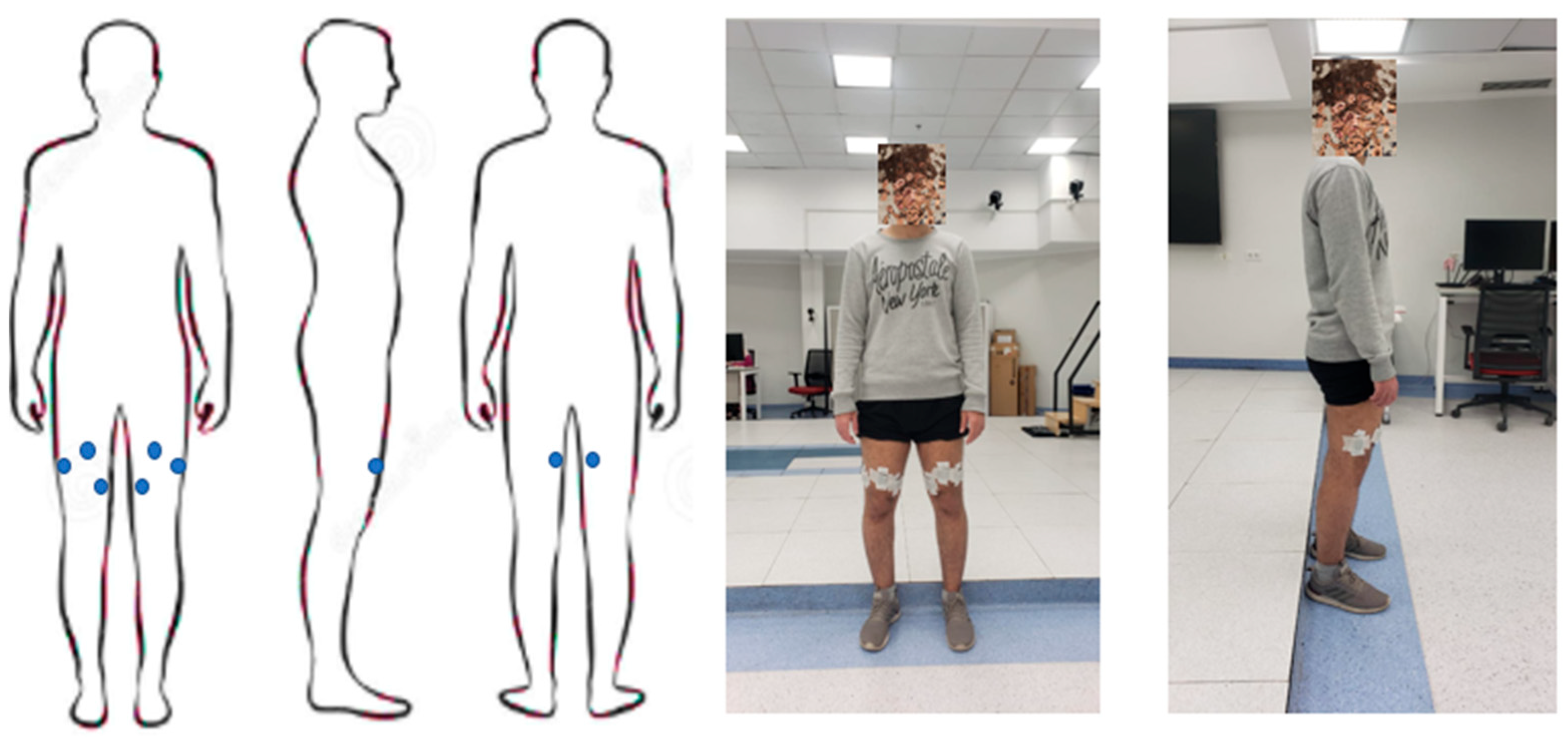

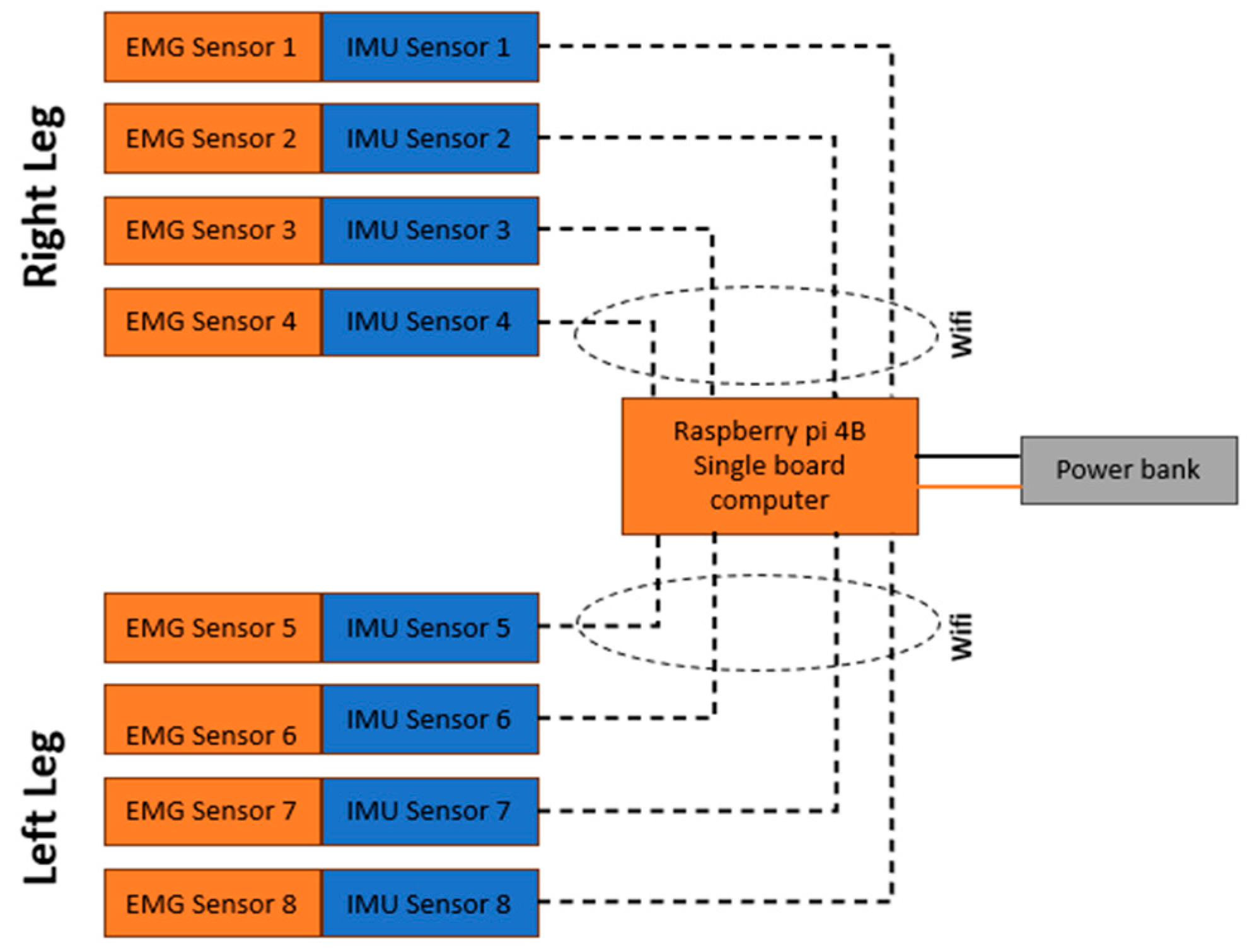

22]. As shown in

Figure 2, a total of 8 sensors were used in the experiments. Each sensor provided 7 signals: 1 surface EMG (sEMG) signal and 6 inertial measurement unit (IMU) signals.

In this study, a sensor module that contains both sEMG and IMU is used for acquiring data signals. SEMG signals and inertial data were acquired and relayed to the Raspberry Pi 4 Model B (8 GB RAM), which served as the central logging unit. Each EMG sensor has a 16-bit resolution with a bandwidth of 20–450 Hz and is sampled at up to 2000 Hz. In addition, body-segment kinematics were captured using a compact 6-DOF inertial measurement unit. The module supports sampling rates up to 200 Hz, with selectable ranges of ±16 g for acceleration and ±2000 °/s for angular velocity. Communication is performed over Wi-Fi through a low-latency 2.4 GHz protocol, with typical end-to-end transmission delays below 10–15 ms during continuous streaming. Indeed, Raspberry Pi 4 Model B was selected as the central processing and logging unit because the overall SDALLE hardware is intended to operate as a wearable, body-mounted acquisition system. Although Wi-Fi is used for data transmission, the system must remain lightweight, low-power, and portable to maintain synchronization with the wearer during locomotor activities.

Electromyography (EMG) is a technique used to study the health of muscles and the motor neurons that control them. It records the electrical signals that cause muscle contractions, but these signals are often complex and need advanced methods for detection, processing, and classification [

23]. EMG signals can be collected using two main types of electrodes: surface and intramuscular. Surface electrodes are widely used because they are non-invasive and easy to apply.

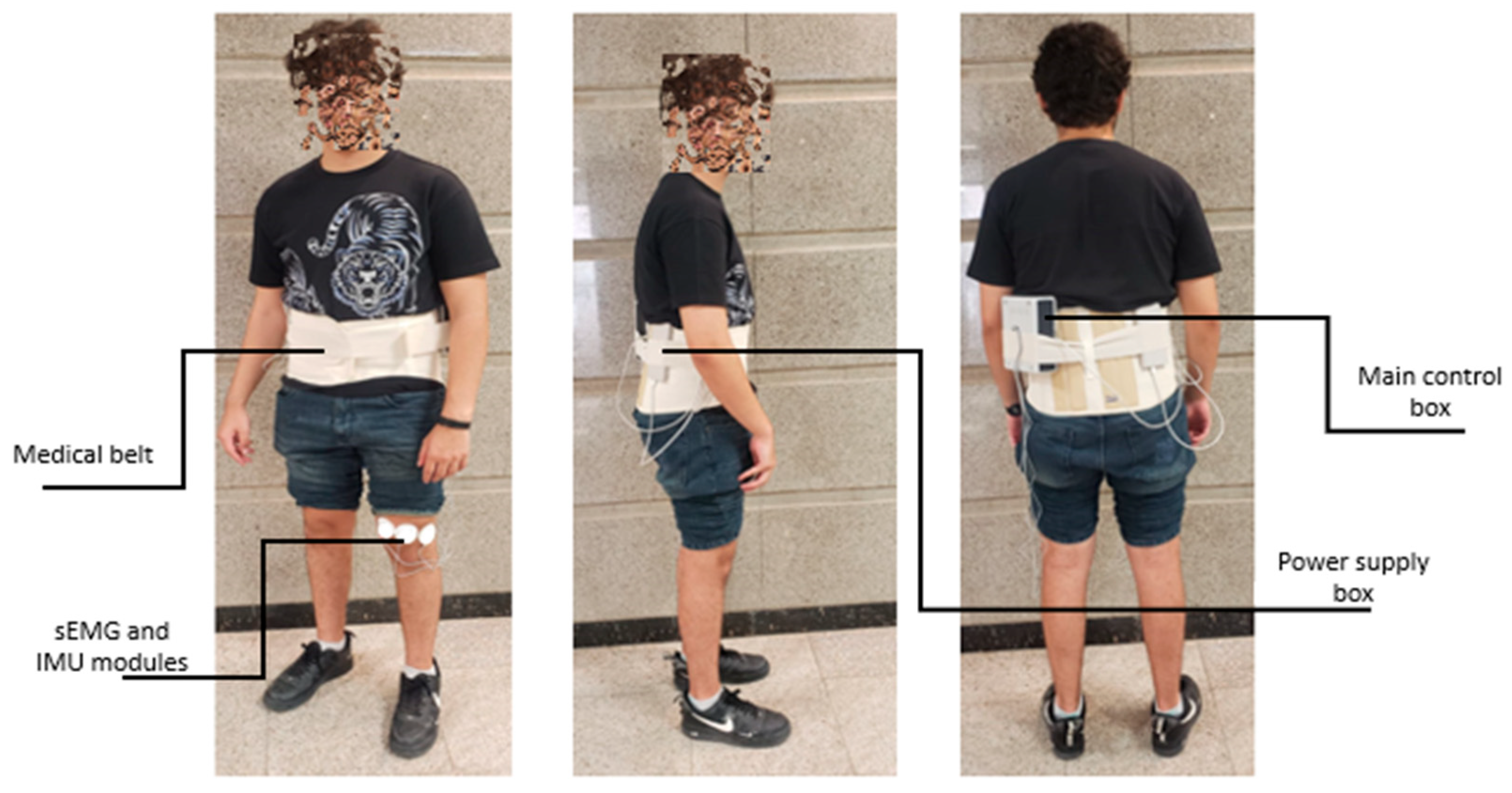

The fully developed DAQ system is shown in

Figure 3. It contains a control box, a power bank, and a medical belt. The control box contains the primary controller for processing and data classification, wireless IMUs, and sEMGs for data collection. The circuit of the system is shown in

Figure 4.

2.2. Experimental Work

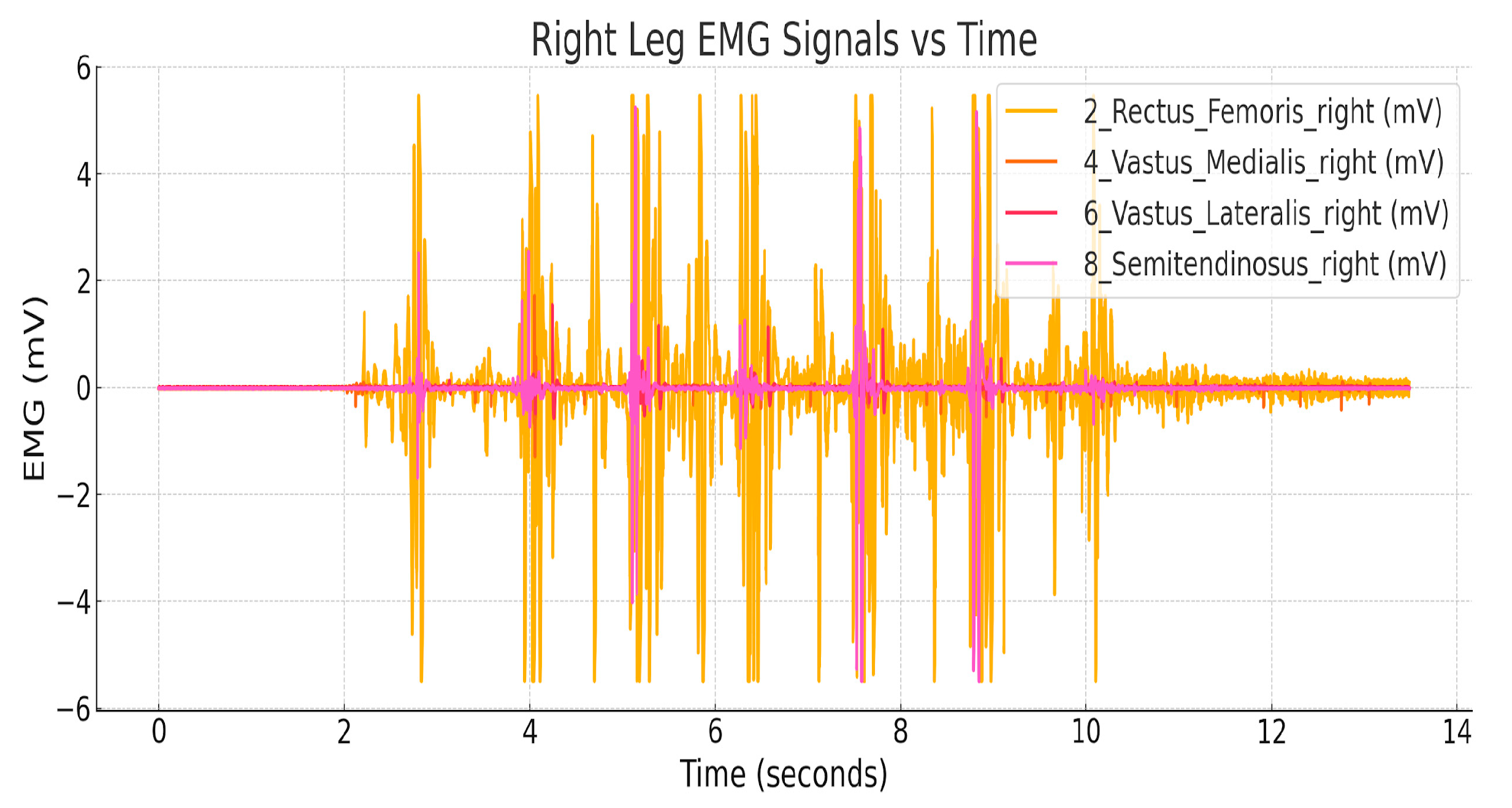

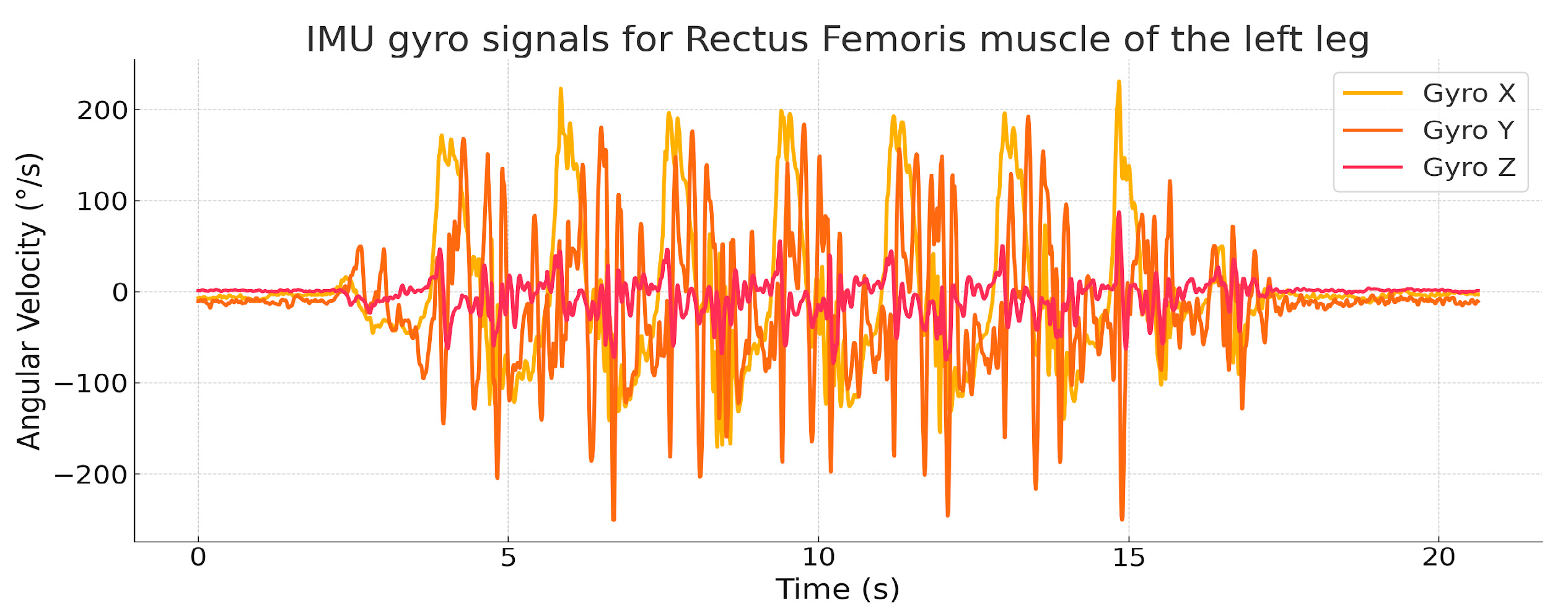

Dynamic activities like walking, jogging, and stairs up and down have been selected for testing the proposed HAR framework. Nine healthy subjects performed 10 trials for each activity while utilizing the SDALLE sensors, and their sensory data were recorded as the SDALLE dataset. The walking experiment was a straight walk at normal speed for 9 m long. Experimental graphs for the EMG signal during walking for a sample subject (subject 3) are shown in

Figure 5. The IMU gyroscope sensory signals were obtained for the same muscle group. A sample graph for gyroscope signals for the left leg of subject 2 is shown in

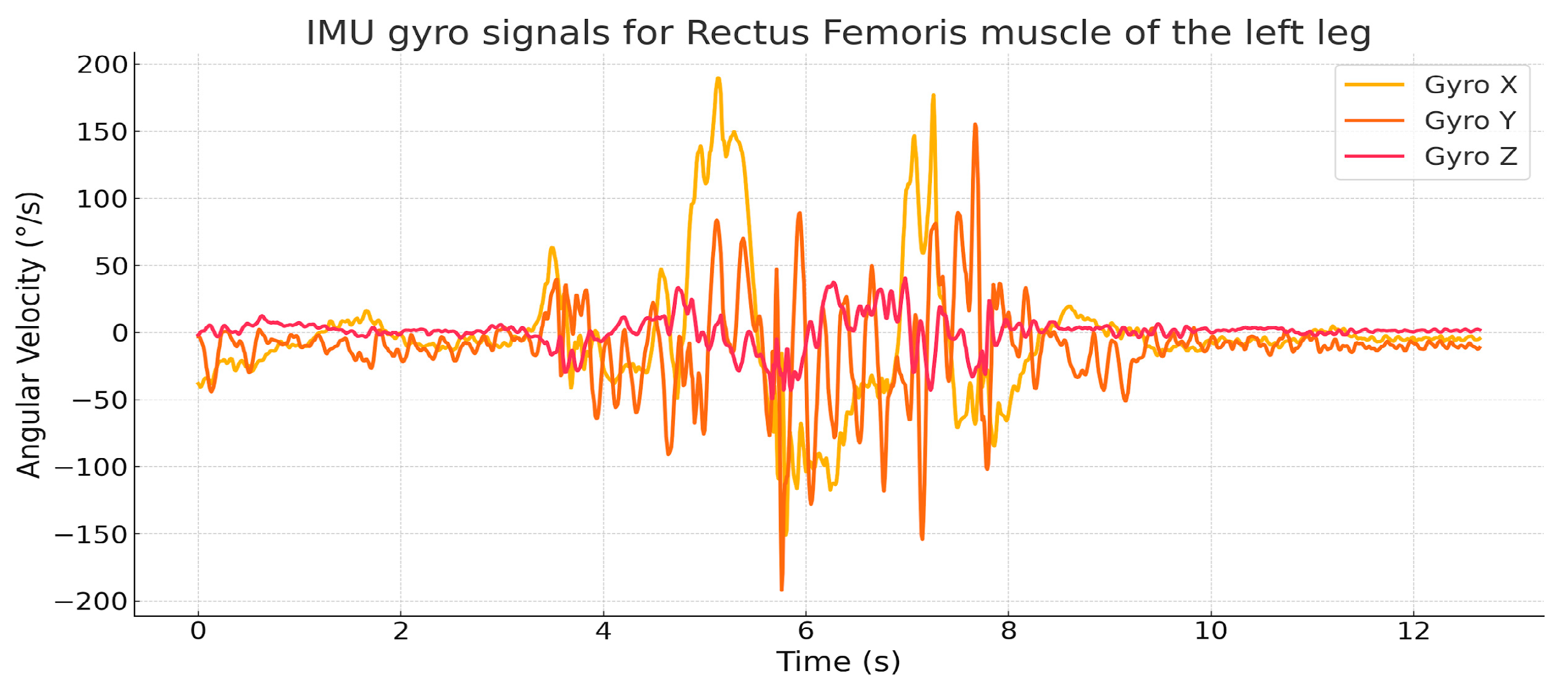

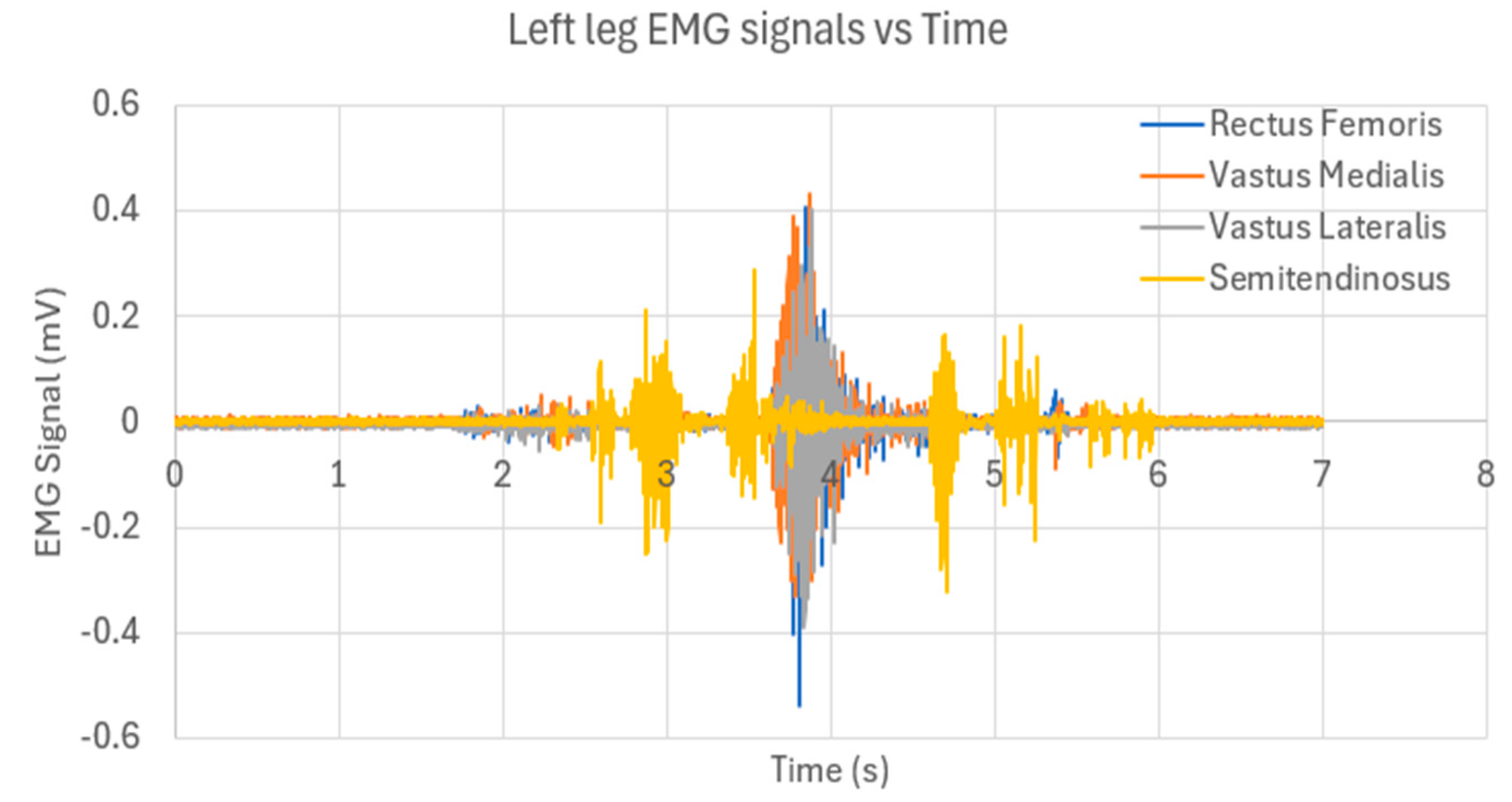

Figure 6. The second activity was jogging, which was performed on the same terrain as walking. The third and fourth activities were going up and down stairs. The stairs were three steps, each having a height of 15 cm. An example of stair up activity was recorded on the muscle on the left leg of subject 3 by EMG and IMU gyroscope signals, as can be seen in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, respectively. As shown in

Figure 8, the EMG signal exhibits a maximum voltage of approximately 0.4 mV. Due to this relatively low amplitude, distinguishing between different movements or classes becomes challenging. The small signal magnitude increases the difficulty for classification models, as the subtle variations in the EMG data require careful feature extraction and preprocessing to achieve accurate discrimination between classes [

24]. The complete experimental readings can be found in the dataset SDALLE [

21].

2.3. Data Preprocessing

The preprocessing stages described below are combined into a single, reproducible pipeline designed to improve signal quality and generalization for wearable activity recognition. To increase the robustness of the model and improve generalization, two data augmentation techniques were applied to the training samples: Jittering and Scaling [

25,

26]. These techniques artificially expand the dataset by generating new variations of the original time series data. First, jittering is used to introduce random noise into the time series, simulating natural variations in real-world signals. Given a time series x = {

,

, …,

, the jittered signal is defined in Equation (1) as:

where

is Gaussian noise with zero mean and standard deviation σ (set to 0.1 in this study). This ensures the model is less sensitive to random fluctuations in the data.

Secondly, a scaling stage is performed on the data where amplitude of the time series data is multiplied by a constant factor. For the original signal, x = {

,

, …,

, the scaled signal is shown in Equation (2) and is expressed as:

In this equation, α is the scaling factor (set to 1.1 in this study). A factor greater than one increases the amplitude, while a factor less than one decreases it. This improves the model’s invariance to differences in signal strength. After applying the augmentation techniques (Jittering and Scaling), the size of the training samples increased from 288 to 864 samples. Each of the four activities (walking, running, stair ascent, and stair descent) is now represented by 234 samples instead of 90 samples, ensuring a balanced and enriched dataset for training and evaluation.

2.4. Signal Denoising

To further enhance the quality of the training data, wavelet denoising was applied to the augmented dataset [

27,

28]. This technique is widely used to suppress noise while preserving important signal characteristics. The denoising procedure consists of three main steps: wavelet decomposition, thresholding, and signal reconstruction.

First, wavelet decomposition was performed using the Daubechies wavelet of order 1 (db1) with a single decomposition level (L = 1). Given a time series x = {

,

, …,

}, the decomposition yields:

where

are the approximation coefficients (low-frequency components) and

are the detail coefficients (high-frequency components).

Secondly, thresholding is performed on data samples. To suppress noise, the detail coefficients are modified using soft thresholding. The threshold λ is estimated to use the median absolute deviation (MAD) of the detail coefficients, where N is the signal length:

The soft thresholding operator is defined in Equation (6). This shrinks the small coefficients to zero while reducing larger ones, effectively removing noise while retaining important features.

Then, the signal is reconstructed using the inverse discrete wavelet transform (IDWT) as can be seen in Equation (7). This produces a cleaned version of the original signal x, with reduced noise and preserved structure.

The denoising procedure was applied to all samples in the augmented dataset (

). For each sample x

i, the function produced a denoised signal

. The resulting dataset, denoted as

, was then used for CNN training:

By applying wavelet denoising, the dataset becomes less sensitive to noise introduced either during data collection or augmentation, allowing the CNN to learn more robust and discriminative features.

2.5. Temporal Convolutional Neural Network (TCNN) Architecture

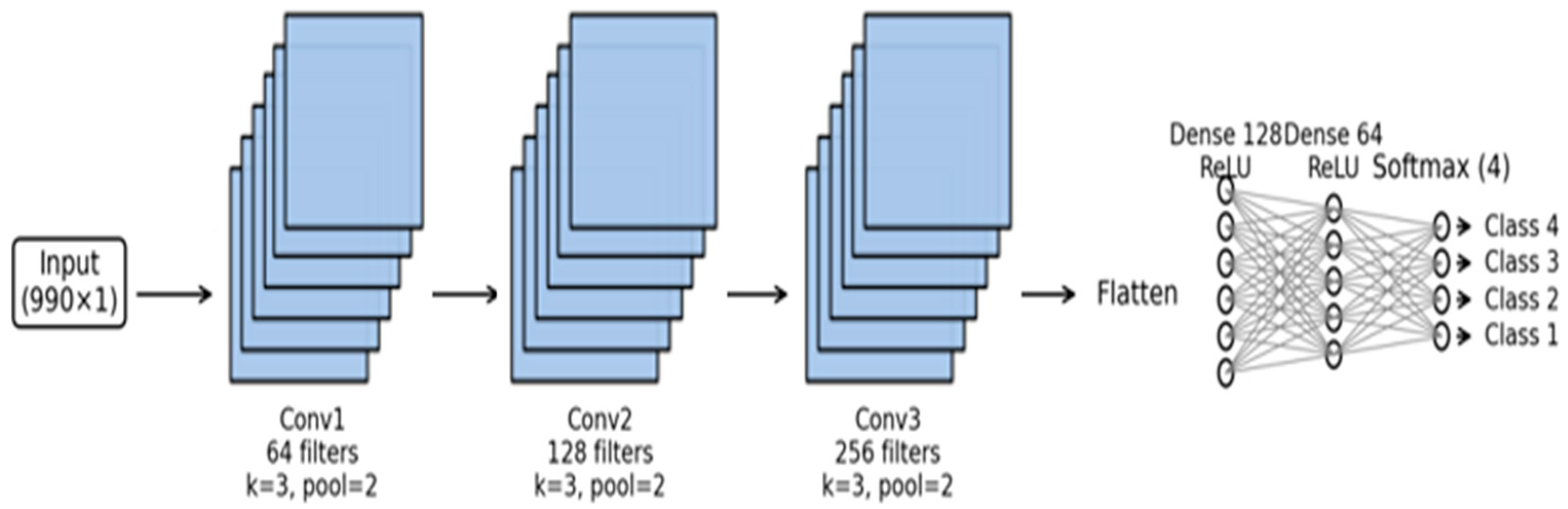

Temporal Convolutional Neural Networks (TCNNs) are chosen for recognizing lower limb activities because they can naturally capture how movements change over time. Instead of relying on hand-crafted features, TCNNs learn patterns directly from sensor signals, such as the rhythm of steps or the difference between level walking and stair climbing. By stacking convolutional layers, the model builds a hierarchy of motion features that make it easier to distinguish between activities. The architecture includes Conv1D, MaxPooling1D, Dropout, Flatten, and Dense layers for hierarchical feature extraction and classification. The model contains approximately 12.4 million parameters, of which around 4.1 million are trainable. For training, the Adam optimizer is employed with its default learning rate of 0.001. The model was trained for 50 epochs using a batch size of 32. The components of the TCNN algorithm are shown in

Figure 9 and are detailed as follows:

Input Layer: The input to the model is defined with shape (990, 1), where 990 represents the number of time steps and 1 is the feature dimension per time step (i.e., a univariate time series).

Convolutional Blocks: Three convolutional blocks were used, each consisting of a convolutional layer, a max-pooling layer, and a dropout layer.

Flatten Layer: The multi-dimensional output of the final convolutional block is flattened into a 1D vector to serve as input for the fully connected layers.

Fully Connected Layers: Two dense layers were included to learn higher-level representations. The first dense layer is 128 units with ReLU activation function while the second dense layer is 64 units with ReLU activation function. A dropout layer is applied after each dense layer for regularization with a value of 0.3.

Output Layer: The final dense layer consists of four units, corresponding to the four activity classes. Softmax activation function is used to output the probability distribution over the classes. The Softmax equation is shown in the following equation:

where C = 4 is the number of classes and z

i is the logit of class i.

3. Results and Discussion

A laptop with an Intel Core i7 CPU running at 2.6 GHz and 16 GB of RAM was used to accomplish the proposed algorithm using MATLAB (R2022). The test was conducted utilizing SDALLE dataset [

21] that included 360 samples from nine able-bodied people for various locomotor modes and consisted of four primary activities (jogging, stair climbing, stair descending, and walking). There are 90 samples in total for every activity. Data is gathered using the SDALLE DAQ system, which includes IMU and EMG sensors. Data on the

Semitendinosus,

Rectus Femoris,

Vastus Medialis,

and Vastus Lateralis muscles have been collected.

Table 2 shows the details of the dataset.

A temporal one-dimensional convolutional neural network (1D-TCNN) was designed to classify time-series sensor signals into four activity categories: walking, running, stair ascent, and stair descent. The model adopts a sequential structure, and its detailed components are detailed in the following subsection. Additionally, a 5-Fold Stratified Cross-Validation procedure was employed to ensure stable and unbiased model evaluation. In this approach, the dataset is divided into five folds while the original class distribution is preserved in each fold. The model is trained in four folds and tested on the remaining fold, and this process is repeated five times. The final performance is reported as the average accuracy computed across all five stratified folds.

3.1. Detailed Classification Performance

The data was acquired using the SDALLE DAQ system, which integrates both inertial measurement unit (IMU) and electromyography (EMG) sensors. EMG data was collected from four major lower limb muscles:

Semitendinosus,

Rectus Femoris,

Vastus Medialis,

and Vastus Lateralis. The efficacy of the proposed method is evaluated by calculating the precision (P), recall (R), and F-measure as given in Equations (10)–(12).

where TP stands for the number of activities that were correctly recognized, FN for the number of activities that were not detected, and FP for the number of activities that were wrongly detected.

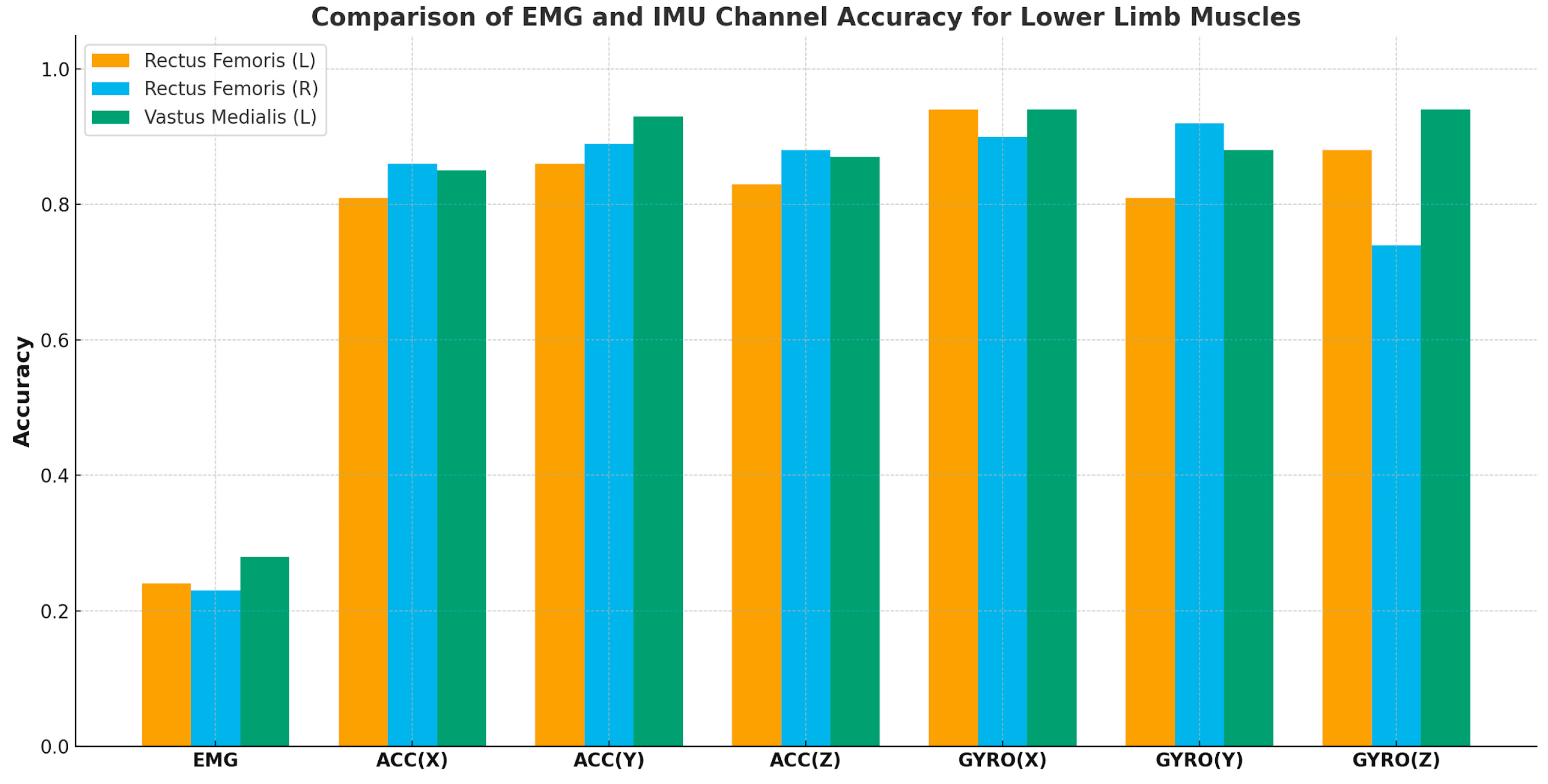

Figure 10 shows the results of EMG and IMU sensors.

The classification results in

Figure 10 show that EMG channels performed poorly across all muscles, with low F-scores and accuracies (e.g.,

Rectus Femoris Left: 0.21 and 0.24). In contrast, IMU signals achieved consistently strong results, with accelerometer accuracies ranging from 0.81 to 0.93 and gyroscopes providing the best performance, reaching up to 0.95. Among all sensors, the

Rectus Femoris (Left) gyroscope in the X-direction stood out as the most discriminative signal, highlighting its effectiveness in capturing gait dynamics for distinguishing between locomotor activities. Overall, these findings confirm that IMU-based measurements, especially gyroscopes, are far more reliable than EMG for lower limb activity recognition in the SDALLE dataset.

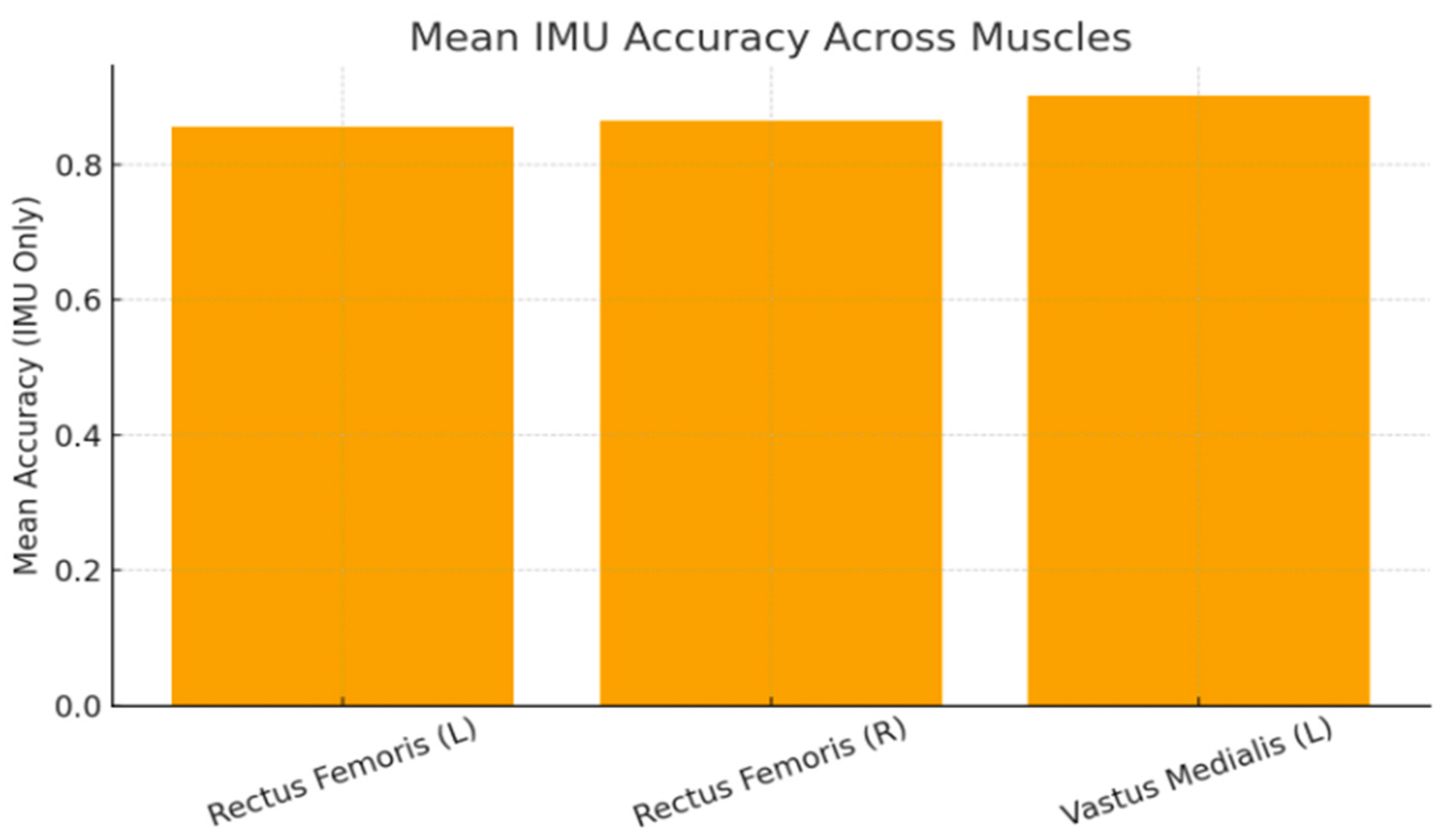

Figure 11 illustrates the mean classification accuracy obtained from the IMU channels across the three monitored muscles. Overall, the

Vastus Medialis (L) achieved the highest average accuracy, followed by the

Rectus Femoris (R), while the

Rectus Femoris (L) recorded the lowest mean performance among the three groups. Despite the variation, all muscles demonstrated consistently high IMU-based accuracy levels, confirming the reliability of IMU signals in capturing lower-limb movement patterns.

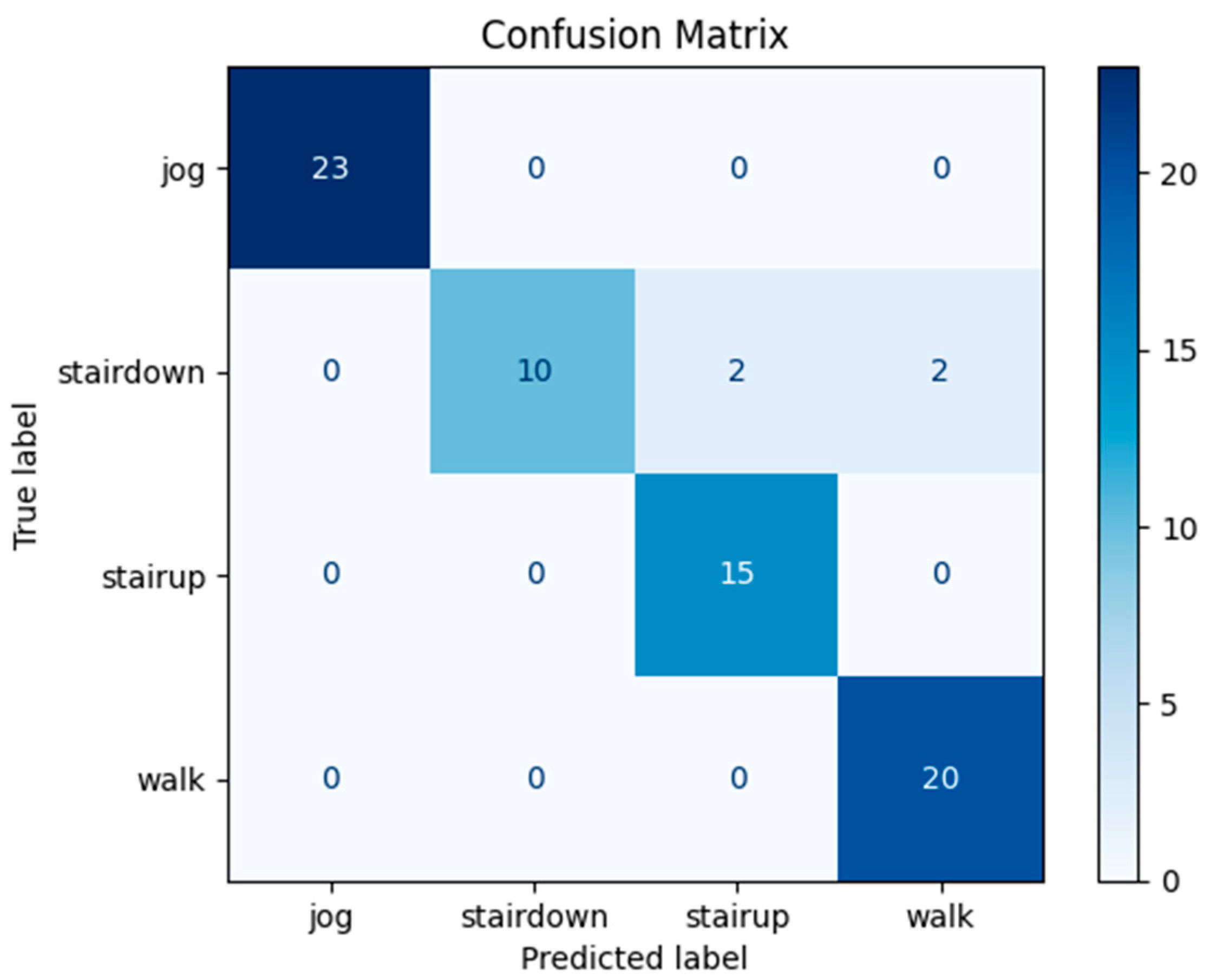

Figure 12 illustrates the confusion matrix corresponding to the classification performance of this signal. The diagonal elements represent correctly classified samples, while the off-diagonal elements indicate misclassifications among the four locomotor activities.

3.2. Discussion

The TCNN model achieved almost perfect classification for jogging, stair ascent, and walking, correctly identifying all instances without error. The only challenge appeared in stair descent, where 10 out of 14 samples were correctly recognized, while a few were misclassified as stair ascent or walking due to their similar motion patterns. Among the monitored muscles, the Rectus Femoris left provided the most discriminative signals, with its gyroscope X-axis channel delivering the highest accuracy. These findings highlight the strength of the model in recognizing most activities and underline the difficulty of distinguishing stair descent from closely related movements. Generally, the confusion matrix demonstrates that the classifier achieved very high accuracy across all activity categories, with only a minor overlap between stair-down and other classes.

From an experimental standpoint, these results provide clear evidence that IMU signals consistently outperform surface EMG signals for lower limb activity classification under wearable conditions. This finding, observed across multiple muscles and confirmed on an independent dataset, suggests that IMU-dominant sensing configurations may be preferable for practical wearable and rehabilitation-oriented applications.

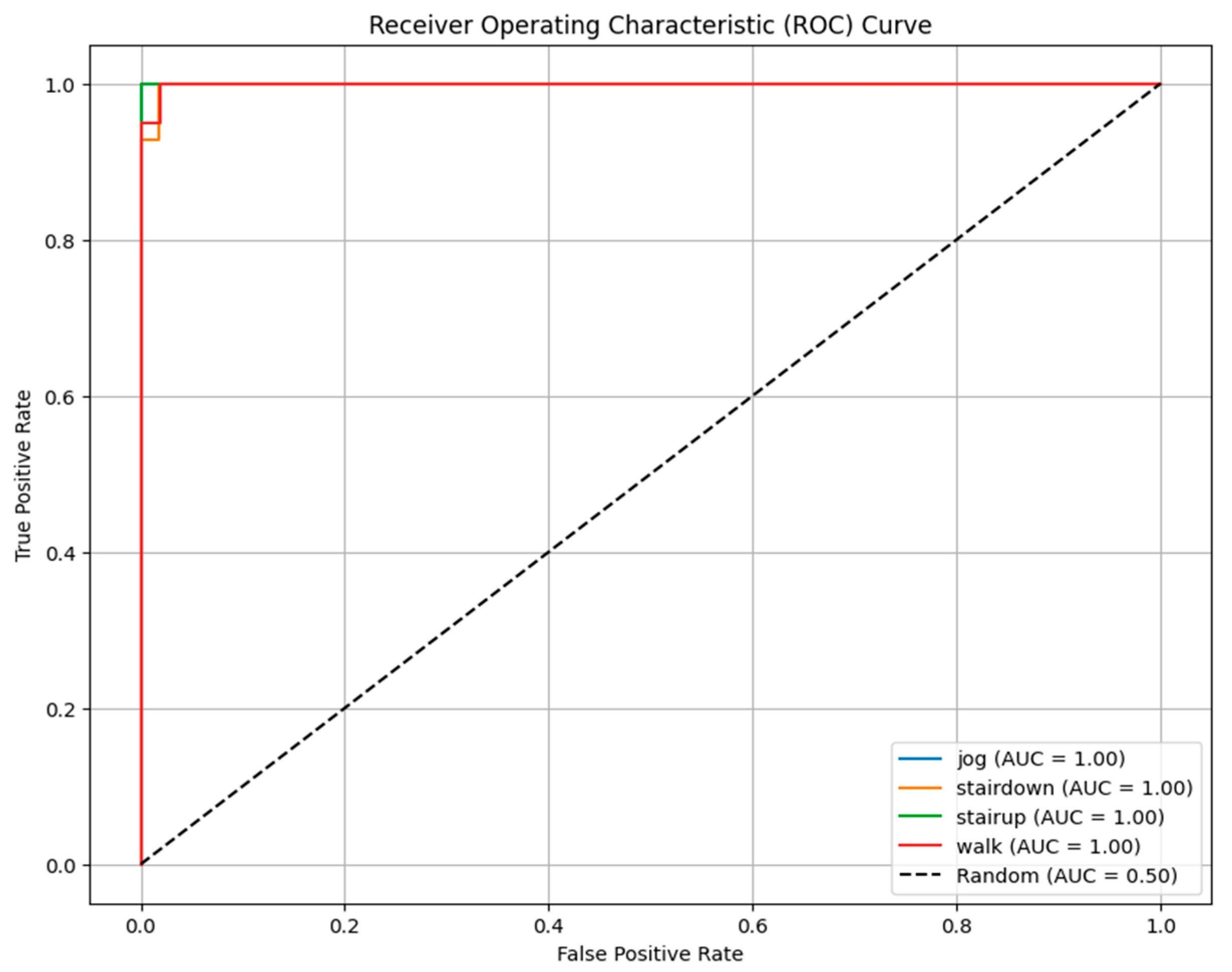

Figure 13 shows the ROC curves of the proposed model, which illustrate the balance between true positives and false positives at different thresholds. All four activities—jog, stair down, stair up, and walk—achieved AUC values of 1.00, with curves tightly clustered near the top-left corner. This indicates that the model can perfectly distinguish between the activities with no overlap or confusion.

These findings are consistent with the confusion matrix results, where the model achieved near-perfect classification performance with only a minor misclassification observed in the stair-down activity. The ROC analysis, therefore, provides strong evidence of the robustness and reliability of the proposed method in activity recognition tasks.

In addition to the deep learning experiments, we performed supplementary analysis using a traditional machine learning model (Random Forest with 100 trees) on multiple features, including mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, median, variance, skewness, and kurtosis. The Random Forest model produced promising classification results across these features. The results presented in

Table 3 focus on two specific muscles: Rectus Femoris left, using IMU gyroscope X-direction signals, and

Vastus Lateralis right, using IMU gyroscope Z-direction signals. These setups exhibited the best classification performance among all tested muscles. The table compares the results obtained using TCNN and Random Forest for these muscles, while the complete set of TCNN and Random Forest results across all muscles and feature combinations are provided in

Appendix A and

Appendix B respectively.

The results in

Table 3 indicate that, for the

Rectus Femoris left (IMU gyroscope X-direction), both TCNN and Random Forest achieved better classification performance. For

Vastus Lateralis right (IMU gyroscope Z-direction), Random Forest outperformed TCNN. These findings highlight that the selected IMU signals and feature combinations are effective for muscle activity classification, and that traditional machine learning models can sometimes achieve results comparable to or better than deep learning approaches.

The HAR results achieved by the SDALLE system were compared to other workbench HAR systems in terms of ADLs, datasets, utilized sensors, and applied algorithms as can be shown in

Table 4. The achieved results highlight the experimental positioning of the proposed system relative to existing HAR studies, emphasizing comparable performance obtained through a newly acquired dataset and the compact sensing configuration.

To further ensure the robustness and generalizability of the proposed model, additional experiments were conducted using an external benchmark dataset, namely the “Georgia Tech dataset” [

32], which includes three primary locomotion activities—walking, stair ascent/descent, and ramp—with a total of 2511 samples collected from 22 healthy adult participants across multiple gait modes. The results demonstrate that our proposed model maintains exceptionally high performance even when tested on data collected independently from our own DAQ system. When using only two individual signals—the gyroscope Y-axis of the shank segment and the gyroscope Y-axis of the foot segment—the model achieved an accuracy of 99%, highlighting its strong discriminative capability and its ability to capture the activities. A comprehensive summary of all results and evaluation metrics for the “Georgia Tech dataset”, is provided in

Appendix C.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

In this study, a hardware data acquisition system (SDALLE) was developed to integrate surface EMG and IMU sensors for lower limb activity recognition. Data was collected from nine participants performing walking, jogging, stair ascent, and stair descent. A temporal convolutional neural network (TCNN) was implemented to classify the activities, and its performance was analyzed across different muscles and sensor channels. The results showed that EMG signals consistently underperformed, with accuracy below 0.30 across the Rectus Femoris (left and right) and Vastus Medialis (left). In contrast, IMU signals provided much higher accuracy, ranging between 0.81 and 0.95. Among them, gyroscope channels—particularly the X-axis of the left Rectus Femoris yielded the best performance, achieving up to 0.95 accuracy. Accelerometer channels also performed well, especially ACC (Y), which reached 0.93 for the Vastus Medialis. The TCNN achieved complete recognition of jogging, stair ascent, and walking, while stair descent showed only minor misclassification with similar motions. ROC curves confirmed strong class separation, with AUC = 1.00 for all activities.

Future work will aim to expand the SDALLE dataset used in this study which includes nine healthy male subjects. This represents a limitation in terms of sample size and demographic diversity. For broader applicability in rehabilitation and assistive exoskeleton contexts, future versions of the dataset will incorporate female participants, older adults, and individuals with mobility impairments to better capture the variability of real time locomotor patterns. Additionally, the SDALLE dataset presents the principal locomotion activities. But it is restricted by the short walking distance and three-step staircase, which limit the amount of sustained steady-state locomotion data. So, longer continuous sequences of walking, jogging, and multi-step staircase locomotion will be addressed. Hence, incorporating extended walkways (≥20 m), multi-floor staircases, and standardized gait-analysis protocols will ensure robustness and clinical relevance. Sensor fusion strategies between EMG and IMU will be investigated to exploit the complementary nature of muscle and kinematic signals. Finally, this study focuses on offline sensing and activity classification and does not address real-time processing, closed-loop control, or robotic actuation. Although our work is considered an essential step, real-time deployment of embedded hardware will be explored to evaluate the feasibility of the proposed approach for wearable rehabilitation robotics.